Abstract

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes mediate mixed-function oxidation reactions important in drug metabolism. The aromatic heterocyclic cation, diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), binds flavin in cytochrome P450 reductase and inhibits CYP-mediated activity. DPI also inhibits CYP by directly interacting with heme. Herein, we report that DPI effectively inhibits a number of CYP-related monooxygenase reactions including NADPH oxidase, a microsomal enzyme activity that generates hydrogen peroxide in the absence of metabolizing substrates. Inhibition of monooxygenase by DPI was time and concentration dependent with IC50's ranging from 0.06 to 1.9 μM. Higher (4.6–23.9 μM), but not lower (0.06-1.9 μM), concentrations of DPI inhibited electron flow via cytochrome P450 reductase, as measured by its ability to reduce cytochrome c and mediate quinone redox cycling. Similar results were observed with inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), an enzyme containing a C-terminal reductase domain homologous to cytochrome P450 reductase that mediates reduction of cytochrome c, and an N-terminal heme-thiolate oxygenase domain mediating nitric oxide production. Significantly greater concentrations of DPI were required to inhibit cytochrome c reduction by iNOS (IC50 = 3.5 µM) than nitric oxide production (IC50 = 0.16 µM). Difference spectra of liver microsomes, recombinant CYPs, and iNOS demonstrated that DPI altered heme-carbon monoxide interactions. In the presence of NADPH, DPI treatment of microsomes and iNOS yielded a type II spectral shift. These data indicate that DPI interacts with both flavin and heme in CYPs and iNOS. Increased sensitivity for inhibition of CYP-mediated metabolism and nitric oxide production by iNOS indicates that DPI targets heme moieties within the enzymes.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, nitric oxide synthase, heme, flavoenzymes, reactive oxygen species

It is well recognized that microsomal enzyme complexes are essential for carrying out many metabolic reactions including xenobiotic transformation. This process is mediated by several successive steps involving electron transport and oxygen activation (Poulos, 2005). Initially, electrons flow from NADPH to cytochrome P450 reductase, a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and a flavin mononucleotide (FMN) containing enzyme. Via an interflavin electron transfer between stable semiquinone FAD/FMN intermediates, there is sequential donation of 2 electrons to the heme-containing cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes (Gutierrez et al., 2002). This latter reaction can simultaneously generate hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a process referred to as oxidase activity or “uncoupling” of the microsomal electron transport chain (De Matteis et al., 2012; Gillette et al., 1957). Interflavin electron transfer within cytochrome P450 reductase can also mediate the reduction of several substrates including cytochrome c and ferricyanide; it can also mediate quinone redox cycling (Guengerich et al., 2009; Lemaire and Livingstone, 1994; Murataliev et al., 2004; Vermilion and Coon, 1978a).

The diaryliodonium salt, diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), is an aromatic heterocyclic cation and a potent arylating agent (Banks, 1966). It is known to inhibit cytochrome P450 reductase, as well as other flavin-containing enzymes including NADPH oxidase (O'Donnell et al., 1993), xanthine oxidase (Doussiere and Vignais, 1992), protoporphyrinogen oxidase (Arnould and Camadro, 1998), mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I (Majander et al., 1994), and several forms of nitric oxide synthase (Stuehr et al., 1991). DPI is thought to function by reacting with flavin cofactors within these enzymes, a process that interferes with electron transport. In the case of cytochrome P450 reductase, DPI modifies reduced FMN and effectively blocks its ability to reduce cytochrome c and quinone redox cycling (Gray et al., 2007; O'Donnell et al., 1994; Wang et al., 2008). The flavin cofactor target in nitric oxide synthase is not well characterized (Stuehr et al., 1991). Alternative sites of action for DPI have also been reported including metal-bound porphyrins and proteins (Doussiere et al., 1999; O'Donnell et al., 1993). DPI has been shown to generate aryl ferric complexes with a synthetic ferrous tetraphenylporphyrin and the heme porphyrin in microsomal CYPs (Battioni et al., 1988) in a manner generally similar to methyl- and phenylhydrazine (Delaforge et al., 1986). The heme component of neutrophil NADPH oxidase is also a target for DPI (Doussiere et al., 1999). As CYP-dependent monooxygenase activity requires both flavins in cytochrome P450 reductase and heme in the CYPs, either or both could be a target for DPI. Similarly, nitric oxide synthases are proteins with flavin-containing C-terminal domains homologous to cytochrome P450 reductase, and N-terminal heme-thiolate oxygenase domains (Stuehr, 1999), each of which has the potential to react with DPI (Stuehr et al., 1991). This study shows that in CYP enzymes and nitric oxide synthase, DPI targets both flavins and heme. Reactions mediated by heme are more sensitive to inhibition than reactions mediated by flavins indicating that DPI preferentially targets heme in these enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials. Recombinant microsomal proteins from baculovirus-infected insect cells containing human NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase enzyme or cytochrome P450 reductase co-expressed with CYP1A2, CYP2E1, or CYP3A4 were obtained from BD Gentest (Woburn, MA). Control liver microsomes and microsomes from pregnenolone-16 α-carbonitrile (PCN)-, dexamethasone (DEX)-, β-naphthoflavone (β-NF)-, isoniazid (ISN)-treated Sprague Dawley rats and human liver microsomes from a mixed gender pool of 50 samples were from XenoTech (Lenexa, KS). Amplex Red (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine) was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Mouse recombinant inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expressed in Escherichia coli (cat No. N2783), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, trichloroacetic acid, p-nitrophenol, horseradish peroxidase, NADPH, glucose, cytochrome c from horse heart, bovine hemin, sodium azide, 30% H2O2, ferricyanide, dibenzylfluorescein, methoxyresorufin, ethoxyresorufin, 7-ethoxycoumarin, menadione, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DETAPAC), and all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Enzyme assays. All enzyme assays were performed in 96-well flat bottom microwell plates. Data were collected using a SoftMax Pro 6.3 software controlled SpectraMax M3 Multimode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA). Unless otherwise described, the enzymatic activities were measured continuously, and linear rates of product formation were analyzed in triplicate. Unless otherwise indicated, DPI, prepared in DMSO (1% final concentration), was added to reaction mixtures prior to NADPH.

For CYP metabolic assays, dibenzylfluorescein, 7-methoxyresorufin, and 7-ethoxyresorufin were used to assess CYP3A, CYP1A2, and CYP1A1 activity, respectively (Ghosal et al., 2003). In order to assess CYP2E1 metabolic activity, either 7-ethoxycoumarin or p-nitrophenol was used as the substrate. Briefly, reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1.0 mM DETAPAC, 5 µM dibenzylfluorescein, methoxyresorufin or ethoxyresorufin, or 500 μM 7-ethoxycoumarin, and 50–100-μg/ml liver microsomal or 25-μg/ml recombinant enzyme proteins in a final volume of 0.1 ml. Reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH and an NADPH-regenerating system (200 μM NADPH, 5.0 mM glucose-6-phosphate, and 1 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, final concentrations). The excitation and emission wavelengths used for CYP substrates were 485 and 530 nm for dibenzylfluorescein, 535 and 580 nm for resorufin, and 380 and 460 nm for 7-hydroxycoumarin. In preincubation experiments, reaction mixtures contained DPI, microsomal proteins, NADPH, and an NADPH-regenerating system and were initiated by the addition of the CYP substrate.

The CYP2E1-dependent conversion of p-nitrophenol to p-nitrocatechol was assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography using a LUNA 250×2 column as described previously (Mishin et al., 1996). Briefly, reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9), 1.0 mM DETAPAC, 20 µM p-nitrophenol, and 500 μg/ml liver microsomal proteins in a final volume of 0.1 ml. Reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH (200 µM). Reactions were terminated using 10 µl 20% trichloroacetic acid and centrifuged at 4000 × g for 20 min before analysis. The amounts of p-nitrocathecol formed were calculated using CLASS-VP V5 software.

Cytochrome P450 reductase–mediated reduction of cytochrome c was assayed by monitoring changes in absorbance at 550 nm as described by Guengerich et al. (2009). Briefly, reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 40 µM cytochrome c and 40 μg/ml microsomal proteins, 1 μg/ml recombinant enzymes or 1 μg/ml iNOS in a final volume of 0.2 ml. Reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH and an NADPH-regenerating system. In preincubation studies, reaction mixtures contained DPI, microsomal proteins, NADPH, and an NADPH-regenerating system and were initiated by the addition of cytochrome c. Cytochrome P450 reductase–mediated reduction of ferricyanide was assayed by measuring changes in absorbance at 420 nm as described by Vermilion et al. (1981). Reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 0.5 mM ferricyanide and 200 μg/ml microsomal or 50 μg/ml recombinant enzyme proteins in a final volume of 0.1 ml. Reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH and an NADPH-regenerating system.

The Amplex Red reaction was used to measure CYP-mediated H2O2 formation in NADPH oxidase assays and in cytochrome P450 reductase-mediated menadione redox cycling assays as previously described (Fussell et al., 2011; Mishin et al., 2010). Briefly, reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 1.0 mM sodium azide, 1.0 mM DETAPAC, and 40 μg/ml microsomal or 10 μg/ml recombinant enzyme protein in a final volume of 0.1 ml. Reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH and an NADPH-regenerating system. For cytochrome P450 reductase–mediated chemical redox cycling, reactions were supplemented with 200 μM menadione, and the linear rate of resorufin formation in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (2.75 units/ml) and Amplex Red (50 µM) was continuously monitored on the microplate reader using excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 585 nm, respectively. H2O2 formation by CYP enzymes was measured by adding horseradish peroxidase (2.75 U/ml) and Amplex Red (50 µM) 5 min after the start of the reactions and immediately recording the fluorescence at a single time point. iNOS as recombinant enzyme was used in the present studies because it was readily available from commercial sources. Nitric oxide production by iNOS in enzyme assays was quantified using an Ionics/Sievers nitric oxide analyzer (GE Instruments, Boulder, CO) (Shi et al., 2013). Briefly, reaction mixtures in a final volume of 50 μl contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mM arginine, 20 μM tetrahydrobiopterin, and 180 μM DTT. Reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH and an NADPH regenerating system. After 5 min, 20 μl of the reaction mixture was assayed for nitrate by reduction-linked chemiluminescence using the nitric oxide analyzer. Argon purged vanadium chloride in 1 M HCl at 95 °C was used as a reducing agent. Data are presented as the concentration of nitric oxide produced by the reaction mixture after 5 min, and assays were performed in triplicate.

The decrease of absorbance at 340 nm was used to analyze the conversion of NADPH to NADP+ by CYP enzymes in the absence of substrate (Wang et al., 2008). Briefly, reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 1.0 mM sodium azide, 1.0 mM DETAPAC, and 0.5 mg/ml microsomal protein or 0.1 mg/ml recombinant protein in a final volume of 0.1 ml. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 200 μM NADPH.

Spectral studies. Heme-binding spectra and carbon monoxide difference spectra were recorded on the SpectraMax M3 Multi-mode Microplate Reader as previously described (Guengerich et al., 2009; Locuson et al., 2007). Reaction mixtures for all spectra contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 2 mg/ml rat liver microsomes from β-NF–treated rats, 40 μM hemin, or 1 mg/ml recombinant iNOS in 1 ml cuvettes. Reaction mixtures were incubated in the presence of DPI or vehicle for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. The reference cuvette for each spectrum contained all components of the reaction mixture except for carbon monoxide. For binding spectra, the sample cuvette contained DPI and the reference cuvette contained vehicle control. Reaction mixtures were incubated in the dark and, after 10 min at room temperature, 100 μM NADPH or a few grains of sodium dithionite was added to both cuvettes and the mixture incubated for an additional 10 min before analysis with or without carbon monoxide.

RESULTS

Effects of DPI on Microsomal CYP Enzyme Activities

Initially, we examined the effects of DPI on the CYP activity of rat liver microsomes from β-NF–treated rats. Using methoxyresorufin as the substrate for CYP1A2, we found that formation of the product, resorufin, was time and NADPH dependent (Figure 1 and not shown). DPI (10 μM) blocked CYP1A2 activity in a time-dependent manner; thus, preincubation of the microsomes with DPI and NADPH for 0 to 20 min increased their sensitivity to inhibition (IC50 = 0.56, 0.15, and 0.03 μM for 0, 5, and 20 min pre-treatments with DPI and NADPH, respectively) (Figure 1). Preincubation of the microsomes with DPI in the absence of NADPH did not increase their sensitivity to inhibition (IC50 = 0.99, 0.79, and 0.81 μM for 0, 5, and 20 min pre-treatments with DPI, respectively) (not shown). These data suggest that DPI binds irreversibly to microsomal electron transport complexes. The reduction of cytochrome c, a marker for cytochrome P450 reductase activity in β-NF microsomes, was also found to be time and NADPH dependent (Figure 1 and not shown). Higher concentrations of DPI (100 μM) were required to inhibit cytochrome c reduction. As observed with CYP1A2 activity, preincubation of microsomes with DPI and NADPH for 0 to 20 min increased the sensitivity of cytochrome c reductase activity to inhibition (IC50 = 8.5, 0.79, and 0.15 μM for 0, 5, and 20 min pre treatments with DPI and NADPH, respectively). However, at each preincubation time with DPI and NADPH (0, 5, or 20 min), CYP1A2 activity was significantly more sensitive to inhibition than cytochrome c reductase activity in the microsomes. Preincubation of the microsomes with DPI in the absence of NADPH did not increase their sensitivity to inhibition (IC50 = 5.48, 8.33, and 6.30 μM for 0, 5, and 20 min pre-treatments with DPI, respectively) (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effects of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) on enzymatic activities of microsomes from β-naphthoflavone (NF)–treated rats. Upper panels: cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2 and cytochrome c reductase activity in microsomes from β-NF treated rats in the absence or presence of DPI. Center panels: time-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2 and cytochrome c reductase activity. Microsomes were preincubated with DPI and NADPH for 0, 5, and 20 min. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Lower panels: CYP-mediated oxidase activity and cytochrome P450 reductase-mediated menadione redox cycling. Assays were run in the absence or presence of DPI. H2O2 formation was measured using the Amplex Red assay.

Similar time-dependent effects of DPI pretreatments were observed with cytochrome P450 reductase and CYP activities in other microsomal preparations and recombinant CYP preparations. In each case, activity associated with CYP was more sensitive to DPI than activity associated with cytochrome P450 reductase (not shown). Enzymatic assays performed to assess the inhibitory potency of DPI on CYP- and cytochrome P450 reductase–dependent activities were thus performed without preincubation with DPI and NADPH. Figure 2 and Table 1 compare the effects of DPI on rat and human liver microsomes as well as recombinant human CYPs when NADPH is added at time zero. CYP1A1 and CYP3A1/2 activities in β-NF microsomes were 11- to 19-fold more sensitive to DPI than cytochrome c reductase activity (Table 1; IC50 = 0.77 and 0.44 μM vs 8.50 μM, respectively). CYP3A1 activity in PCN- and DEX-treated rat liver microsomes was 85- and 143-fold more sensitive to inhibition by DPI than cytochrome c reductase activity (Table 1; IC50 = 0.06 and 0.07 μM vs 5.10 and 10.0 μM, respectively). CYP2E1 activity in ISN rat liver microsomes was 16- to 25-fold more sensitive to DPI than cytochrome c reductase activity (Table 1 and Figure 2; IC50 = 0.62 μM using 7-ethoxycoumarin as the substrate and 0.99 µM using p-nitrophenol as the substrate vs 15.70 μM). It should be noted that, although 1% DMSO is known to inhibit CYP2E1 activity, the presence of this solvent did not affect the sensitivity of 7-ethoxycoumarin hydroxylase activity in ISN rat liver microsomes to DPI (IC50 = 0.32 µM, 0.33 µM, and 0.31 µM in the presence of 1%, 0.1%, and 0% DMSO, respectively) (not shown). CYP3A1/2 activity in ISN rat liver microsomes was 14-fold more sensitive to DPI than cytochrome c reductase activity (Table 1 and Figure 2; IC50 = 1.16 vs 15.70 μM), and CYP3A2 activity in control rat liver microsomes was 16-fold more sensitive than cytochrome c reductase activity (IC50 = 0.29 vs 4.60 μM). CYP activity in human liver microsomes and human recombinant CYPs (1A2, 2E1, and 3A4) were also more sensitive to DPI than cytochrome c reductase activity. Thus, we found that CYP activity was 11-12-fold more sensitive to DPI for these enzymes, when compared with activity for cytochrome c reduction (Table 1 and Figure 2). The sensitivity of cytochrome c reductase activity to DPI in human recombinant cytochrome P450 reductase was generally similar to the rat and human microsomes and the human recombinant CYPs co-expressed with cytochrome P450 reductase (Table 1 and Figure 2; IC50 = 16.7 μM).

FIG. 2.

Effects of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) on cytochrome P450 reductase and cytochrome P450 (CYP) activities in native liver microsomes and recombinant enzymes. All enzyme assays were performed as described in the Materials and Methods. Black symbols represent cytochrome P450 reductase-mediated activities; white symbols represent CYP-mediated activities. Data for NADPH oxidation are results of duplicate measurements. Data in all other assays are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Enzyme reactions were run without preincubations with DPI Enzyme activities included FeCN reduction (red.) and cytochrome c reduction (red.).

TABLE 1. Summary of the Effects of DPI on the Cytochrome P450 Reductase and CYP Enzyme Reactions in Recombinant CYP450 Enzymes, Human Liver Microsomes, and Rat Liver Microsomes.

| Cytochrome P450 Reductase–Mediated Activity [IC50 (μM)a] |

CYP-Mediated Activity [IC50 (μM)] |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menadione Redox Cycling | Cytochromec Reduction | Ferricyanide Reductionb | NADPH Oxidation | H2O2 Formation | CYP Activityc | |||

| Rat liver microsomes | ||||||||

| CTLd | 4.84 | 4.60 | >100 | ND | 0.17 | 0.29 | 3A2 | 15.90 |

| DEX | 23.61 | 10.00 | >100 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 3A1 | 142.90 |

| PCN | 13.76 | 5.10 | >100 | 0.35 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 3A1 | 85.00 |

| β-NF | 9.72 | 8.50 | >100 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.77 | 1A1 | 11.00 |

| 0.56 | 1A2 | 15.20 | ||||||

| 0.44 | 3A1/2 | 19.30 | ||||||

| ISN | 21.32 | 15.70 | >100 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 0.62e (0.99)f 1.16 | 2E1 3A1/2 | 25.30e (15.89)f 13.50 |

| Human enzymes | ||||||||

| P450 Reductaseg | 9.28 | 16.70 | >100 | — | — | — | 9.40 | |

| CYP1A2 | 6.06 | 18.00 | >100 | 0.56 | 1.40 | 1.90 | 1A2 | 61.30 |

| CYP2E1 | 12.39 | 23.91 | >100 | 0.25 | 1.70 | 0.39 | 2E1 | 22.30 |

| CYP3A4 | 12.90 | 14.50 | >100 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 3A4 | 11.90 |

| Liver microsomes | 12.15 | 8.90 | >100 | ND | 0.51 | 1.20 | 1A1 | 7.40 |

| 0.82 | 1A2 | 10.85 | ||||||

| 1.10e | 2E1 | 8.09 | ||||||

| 0.75 | 3A4/5 | 9.40 | ||||||

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

aIC50 values were measured without preincubations with DPI and NADPH.

bDPI did not inhibit the reduction of ferricyanide by cytochrome P450 reductase.

cSubstrates used to evaluate CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP3A activities were 7-ethoxyresorufin, 7-methoxyresorufin, and dibenzylfluorescein, respectively.

dControl (CTL), β-NF, and ISN microsomes were from male rats. PCN and DEX microsomes were from female rats.

eDetermined using 7-ethoxycoumarin as the substrate. 7-ethoxycoumarin is also known to be metabolized by CYP1A1, 1A2, and 2B1 in rat liver microsomes and 1A2 in human liver microsomes.

fDetermined using p-nitrophenol as the substrate.

gP450 reductase, CYP1A2, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 are recombinant human enzymes expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells.

It is well recognized that the CYPs also exhibit NADPH-dependent “oxidase” activity where the spontaneous oxidation of NADPH leads to the formation of H2O2 (Mishin et al., 2014). Each of the microsomal preparations and human recombinant CYPs readily generated H2O2 (Figure 1 and Table 1 and not shown). Both substrate-independent H2O2 formation and NADPH oxidation by microsomes were blocked by DPI (Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 1). The sensitivity of these activities to DPI was similar to the CYP metabolic activity (IC50 = 0.17–1.70 μM for H2O2 formation and 0.22–0.56 μM for NADPH oxidation, respectively), and significantly more sensitive to inhibition than cytochrome P450 reductase mediated reduction of cytochrome c.

Cytochrome P450 reductase is also known to mediate chemical redox cycling, a process that generates H2O2 (Wang et al., 2010). Using menadione as a redox cycling quinone, we found that the sensitivity of rat and human liver microsomes, as well as recombinant human cytochrome P450 reductase and CYP preparations, to DPI, was generally similar to their sensitivity to cytochrome c reduction by DPI (IC50 = 4.84–23.61 μM; Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 1). This was significantly less than their sensitivity to inhibition of CYP metabolic activity, as well as oxidase activity, by DPI. Cytochrome P450 reductase also reduces ferricyanide in the presence of NADPH (Vermilion and Coon, 1978b). Under our experimental conditions, DPI (up to 100 µM) had no significant effect on reduction of ferricyanide in any of the microsomal preparations or recombinant enzymes examined (Figure 2 and Table 1).

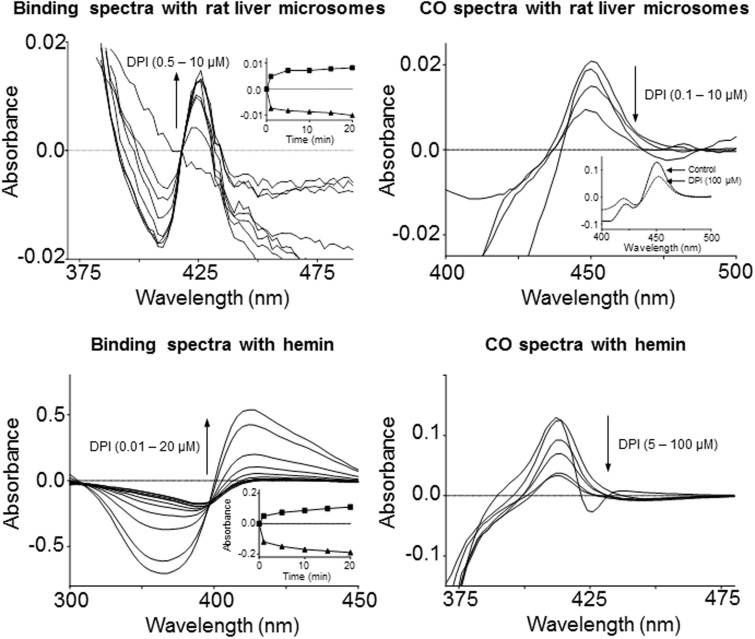

Spectral Analysis of CYP450 and iNOS

The reduced and oxidized intermediate states of heme-containing proteins can be identified by specific spectral characteristics, and interconversion of these different states provides insights into reaction mechanisms. Spectral intermediates are identified based on changes in the Soret bands of heme, as well as in the visible spectrum. We next examined the spectral characteristics of CYP heme and free hemin following DPI treatment using difference spectrophotometry. The difference spectrum of carbon monoxide–bound CYP heme and free hemin displayed characteristic peaks at 450 and 412 nm, respectively (Figure 3). DPI caused a concentration-dependent reduction in the height of peaks at concentrations as low as 5 μM for hemin and 0.1 μM for the microsomes. A characteristic type II spectral shift with a trough at 416 nm and peak at 426 nm was present in the difference spectrum of CYP in the presence of NADPH and DPI (Figure 3). In the absence of NADPH, DPI did not induce any spectral changes in rat liver microsomes (not shown). In free hemin, DPI induced a similar spectral shift with a trough at 366 nm and a peak at 426 nm. The intensity of the spectral changes was dependent on the concentration of DPI with both CYP heme and free hemin. With both microsomes and hemin, the effects of DPI were time dependent (Figure 3, insets).

FIG. 3.

Effects of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) on the spectral properties of rat liver microsomes and hemin. Spectra were recorded using liver microsomes from β-naphthoflavone–treated rats (upper panels) and hemin (lower panels). Carbon monoxide (CO) difference spectra (right panels) and binding spectra (left panels) were performed as described in Materials and Methods. CO difference spectra included NADPH as the reductant for rat liver microsomes and sodium dithionite for hemin, respectively. The reference cuvette for CO spectra contained all components in the sample cuvette except CO. Binding spectra for microsomes included NADPH as the reductant; no reductant was used for the hemin binding spectra. The reference cuvette for binding spectra contained all components in the sample cuvette except DPI. Insets: Left panels: time-dependent effects of DPI (1 μM) on the absorbance at the trough (▲, 410 and 366 nm for microsomes and hemin, respectively) and peak (▪, 424 and 426 for microsomes and hemin, respectively) of the binding spectra of rat liver microsomes and hemin. Reactions with microsomes and hemin were initiated with the addition of 100 μM NADPH or DPI, respectively. Upper right panel: dithionite reduced CO spectra in the presence and absence of DPI.

Nitric oxide synthase is a dual flavin-containing cytochrome c reductase; it also possesses heme-dependent nitric oxide–generating activity (White and Marletta, 1992). We found that DPI inhibits both the cytochrome c reductase and the nitric oxide generating activity of iNOS (Figure 4). Approximately 20-fold higher concentrations of DPI were required to inhibit cytochrome c reductase activity of iNOS when compared with nitric oxide production (IC50 = 3.50 and 0.16 µM, respectively). DPI was also found to alter the spectral properties of iNOS. Reduced iNOS generated a carbon monoxide spectrum with a characteristic peak at 447 nm. A concentration-dependent decrease in peak height was noted in the presence of DPI (Figure 4).

FIG. 4.

Effects of DPI on iNOS. Left panel: the effects of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) on nitric oxide (NO) production and cytochrome c reduction by iNOS were measured as described in the Materials and Methods. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Right panel: the carbon monoxide (CO) difference spectra of iNOS were recorded in the absence and presence of DPI. Assays were run without preincubations with DPI using sodium dithionite as a reductase.

DISCUSSION

DPI is an arylating agent that acts via a radical-based mechanism. Initial abstraction of an electron from a nucleophile by DPI generates a phenyl radical, this radical then adds back to a nucleophile to form covalent adducts (O'Donnell et al., 1994). The best characterized DPI adducts are with flavin cofactors in enzymes and, based on these data, DPI has been widely used as a flavoenzyme inhibitor (Basu et al., 2014; Chiapella et al., 2000; Cross et al., 1990; Venkatachalam et al., 2008). However, the actions of DPI are not enzyme specific; thus, many flavoenzymes, including cytochrome P450 reductase, are inhibited by DPI (O'Donnell et al., 1994). The present studies confirmed that DPI is an effective inhibitor of cytochrome P450 reductase in rat and human liver microsomes, in recombinant cytochrome P450 reductase, and in recombinant CYPs co-expressed with cytochrome P450 reductase. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 reductase by DPI was also found to block electron transfer to CYPs resulting in inhibition of their monooxygenase activity. Inhibition of these enzyme activities was time dependent. These findings are consistent with the idea that DPI is a mechanism-based inhibitor (McGuire et al., 1998).

In earlier studies, DPI was also shown to modify heme moieties in microsomal CYPs and neutrophil NADPH oxidase (Battioni et al., 1988; Doussiere et al., 1999). In the case of NADPH oxidase, 2 components of the enzyme, FAD and heme b, could be modified by DPI (Doussiere et al., 1999). However, our spectral studies showed that DPI caused a decrease in NADPH oxidase activity that was directly correlated with decreases in the absorbance of the Soret peak of flavocytochrome b in NADPH-treated neutrophil membranes, indicating that heme is the predominant target for DPI.

Our studies also showed that DPI reacts with CYP heme in liver microsomes generating characteristic type II difference spectra, as well as decreases in the carbon monoxide difference spectra. These data indicate that DPI can alter the CYP heme thiolate structure (Locuson et al., 2007; Omura and Sato, 1964). Changes in the heme spectra occurred at concentrations of DPI that inhibited CYP, but not cytochrome P450 reductase, also supporting the idea the heme is an important target for DPI. The actions of DPI were not limited to CYP heme as the difference spectrum of hemin, a simple ferric iron ion containing protoporphyrin IX with a chloride ligand, showed similar changes in its type II spectra and carbon monoxide difference spectra after DPI treatment. Taken together, these data provide additional support for the idea that DPI reacts with heme structures.

As CYP-mediated reactions require both the flavoenzyme cytochrome P450 reductase as the electron donor, and heme-containing CYP for monooxygenase activity, a question arises as to whether DPI preferentially targets the flavoenzyme or heme in the CYPs. To address this, we performed a dose–response analysis of the different metabolic reactions performed by the 2 components of the CYP complexes. For cytochrome P450 reductase, we quantified the effects of DPI on cytochrome c reduction and menadione redox cycling, and for CYP, we measured CYP-mediated substrate metabolism, NADPH oxidation and oxidase activity. In all liver microsomal preparations including human microsomes, control rat microsomes and microsomes from rats treated with DEX, PCN, β-NF, or ISN, as well as human recombinant CYP1A2, 2E1 and 3A4, reactions mediated by CYP heme were markedly more sensitive to inhibition by DPI than the flavin-dependent reactions mediated by cytochrome P450 reductase. The activities of recombinant cytochrome P450 reductase were similar to those of the recombinant enzymes and the microsomes. Of the best characterized CYP system reactions (reduction of cytochrome c and CYP monooxygenase activity), DPI-mediated inhibition of CYP activity was 9.4- to 22.3-fold more sensitive than inhibition of cytochrome c reduction in recombinant enzymes and 11.0- to 143-fold more sensitive in the liver microsomes. These data, together with our findings that concentrations of DPI that inhibit CYP activity, but not cytochrome P450 reductase activity, induce a type II difference spectra, support the idea that DPI selectively targets heme in the CYP complex. Also of note were our findings that differences in sensitivity to DPI in reactions mediated by cytochrome P450 reductase and CYP were independent of DPI pretreatments of the enzyme preparations. Thus, although the sensitivity of each of the reactions increased following pretreatment with the inhibitor, CYP-mediated reactions remained more sensitive to DPI than cytochrome P450 reductase–mediated reactions. These data further support the idea of similar reactivity via a mechanism-based reaction to the flavin and heme-binding sites of the CYP complex.

When comparing reactions in different recombinant CYP preparations, sensitivity to DPI was generally similar. However, with microsomal preparations, more variation was noted, presumably due to greater variability in content of CYP complex enzymes, as well as non-CYP components in the microsomes. Of particular interest were our findings that DPI was unable to inhibit reduction of ferricyanide in any of the recombinant or microsomal preparations (IC50 > 100 µM). It has long been recognized that cytochrome P450 reductase mediates the 1 electron reduction of ferricyanide in a reaction mediated by FAD (Kurzban and Strobel, 1986; Vermilion and Coon, 1978b; Vermilion et al., 1981). In fact, FMN-free cytochrome P450 reductase retains the ability to reduce ferricyanide, but not reduction of cytochrome c (Vermilion et al. 1981). Similarly, site-directed mutagenesis of Tyr-178 in cytochrome P450 reductase blocks FMN binding and cytochrome c reductase activity; however, the mutant enzyme retains ferricyanide reductase activity in direct correlation with its FAD content (Shen et al., 1989). Similarly, mutations in neuronal nitric oxide synthase acidic and aromatic residues in the FMN binding domain destabilizes FMN enzyme binding, which also results in a loss of cytochrome c reductase activity but not ferricyanide reductase activity (Adak et al., 1999). These data are consistent with earlier findings that DPI directly binds to FMN in cytochrome P450 reductase and the fact that FMN is critical for mediating the 1 electron reduction of cytochrome c (Huang et al., 2015; Tew, 1993). As the 1 electron reduction of menadione during redox cycling is also inhibited by DPI, it appears that FMN is required for this reaction. In this regard, menadione redox cycling has also been reported to be inhibited in FMN-depleted cytochrome P450 reductase (Gherasim et al., 2008; Vermilion et al., 1981). Similarly, in another diflavin oxidoreductase, methionine synthase reductase, which is known to possess cytochrome c reductase and menadione redox cycling activity, a mutant enzyme with destabilized FMN binding, displays only a limited capacity to carry out these reactions (Gherasim et al., 2008; Vermilion et al., 1981), further supporting the idea that FMN mediates quinone redoxy cycling.

Like the CYP complex, nitric oxide synthases contain a reductase domain homologous to cytochrome P450 reductase that mediates electron transfer from NADPH to a heme-thiolate oxygenase domain; in the case of nitric oxide synthase, this domain mediates nitric oxide production from L-arginine. Using iNOS, we found that significantly greater concentrations of DPI were required to inhibit cytochrome c reduction (IC50 = 3.50 µM) than nitric oxide production (IC50 = 0.16 µM). Difference spectra using recombinant iNOS demonstrated that DPI altered the interaction between heme and carbon monoxide causing a decrease in the magnitude of the absorption peak at 450 nm. Overall, our data indicate that DPI interacts with both flavin and heme in CYPs and iNOS. Increased sensitivity for inhibition of CYP-mediated metabolism and nitric oxide production by iNOS indicates that DPI selectively targets heme moieties in the enzymes.

It should be noted that, in addition to the CYPs, cytochrome P450 reductase is an electron donor protein for heme oxygenase and several other enzymes including cytochrome b5, squalene monooxygenase and 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (Porter, 2012). Targeting flavin in cytochrome P450 reductase by DPI would be expected to inhibit these enzyme activities. However, heme oxygenase is also a heme-containing protein (Schuller et al., 1999; Strittmatter, 1960). A comparison of DPI-binding sites in this enzyme complex is required to determine whether, like CYP and iNOS, there is preferential targeting of heme. Although cytochrome b5 also contains heme, it is unlikely to be a target for DPI due to biscoordination with His residues at its fifth and sixth ligands (Delaforge et al., 1986).

Based on its ability to react with heme and inhibit heme-dependent reactions over flavin-dependent cytochrome P450 reductase- and iNOS-related reactions, we conclude that DPI preferentially binds to heme. At the present time, mechanisms mediating targeting of heme in the CYP system and iNOS are not known. It may be that the reaction of DPI with heme is kinetically more favorable than reactions with flavin in the enzymes. Alternatively, heme may be more accessible to modification in the enzymes, possibly through their substrate access channels. Cationic pathways for DPI-induced modifications with biological targets have also been proposed. These pathways, along with radical-mediated pathways, are supported by data with arylations taking place on SP2 aromatic carbons, enolic methylenes, and a variety of other nucleophiles (Aggarwal and Olofsson, 2005; Chakraborty and Massey, 2002; Jalalian et al., 2011; Modha and Greaney, 2015; Wen et al., 2012). It is possible that the mechanism by which DPI reacts with flavins is distinct from its reactions with heme. Further studies are needed to more precisely define the mechanism(s) by which DPI interacts with CYP and iNOS to alter their functioning.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant U54AR055073); the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant U01NS079249); and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grants R01ES004738, R01ES021800, and P30ES005022).

REFERENCES

- Adak S., Ghosh S., Abu-Soud H. M., Stuehr D. J. (1999). Role of reductase domain cluster 1 acidic residues in neuronal nitric-oxide synthase. Characterization of the FMN-free enzyme. J Biol Chem 274, 22313–22320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal V. K., Olofsson B. (2005). Enantioselective alpha-arylation of cyclohexanones with diaryl iodonium salts: application to the synthesis of (-)-epibatidine. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 44, 5516–5519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnould S., Camadro J. M. (1998). The domain structure of protoporphyrinogen oxidase, the molecular target of diphenyl ether-type herbicides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 10553–10558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks D. F. (1966). Organic polyvalent iodine compounds. Chem. Rev. 66, 243–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Rajakaruna S., Dickinson B. C., Chang C. J., Menko A. S. (2014). Endogenous hydrogen peroxide production in the epithelium of the developing embryonic lens. Mol Vis 20, 458–467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battioni J. P., Dupré D., Delaforge M., Jaouen M., Mansuy D. (1988). Réactions des dérivés de l'iode(III) avec les ferroporphyrines et le cytochrome P-450: Formation de complexes σ-aryles du fer(III) et de N-aryl-porphyrines du fer(II) à partir de sels de diaryliodonium. J. Organomet. Chem. 358, 389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Massey V. (2002). Reaction of reduced flavins and flavoproteins with diphenyliodonium chloride. J Biol Chem 277, 41507–41516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiapella C., Radovan R. D., Moreno J. A., Casares L., Barbe J., Llagostera M. (2000). Plant activation of aromatic amines mediated by cytochromes P450 and flavin-containing monooxygenases. Mutat Res 470, 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A. R., Henderson L., Jones O. T., Delpiano M. A., Hentschel J., Acker H. (1990). Involvement of an NAD(P)H oxidase as a pO2 sensor protein in the rat carotid body. Biochem J 272, 743–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis F., Ballou D. P., Coon M. J., Estabrook R. W., Haines D. C. (2012). Peroxidase-like activity of uncoupled cytochrome P450: studies with bilirubin and toxicological implications of uncoupling. Biochem Pharmacol 84, 374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaforge M., Battioni P., Mahy J. P., Mansuy D. (1986). In Vivo formation of sigma-methyl- and sigma-phenyl-ferric complexes of hemoglobin and liver-cytochrome P-450 upon treatment of rats with methyl- and phenylhydrazine. Chem Biol Interact 60, 101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doussiere J., Gaillard J., Vignais P. V. (1999). The heme component of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase complex is a target for aryliodonium compounds. Biochemistry 38, 3694–3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doussiere J., Vignais P. V. (1992). Diphenylene iodonium as an inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase complex of bovine neutrophils. Factors controlling the inhibitory potency of diphenylene iodonium in a cell-free system of oxidase activation. Eur J Biochem 208, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussell K. C., Udasin R. G., Gray J. P., Mishin V., Smith P. J., Heck D. E., Laskin J. D. (2011). Redox cycling and increased oxygen utilization contribute to diquat-induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells overexpressing NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Free Radic Biol Med 50, 874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherasim C. G., Zaman U., Raza A., Banerjee R. (2008). Impeded electron transfer from a pathogenic FMN domain mutant of methionine synthase reductase and its responsiveness to flavin supplementation. Biochemistry 47, 12515–12522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal A., Hapangama N., Yuan Y., Lu X., Horne D., Patrick J. E., Zbaida S. (2003). Rapid determination of enzyme activities of recombinant human cytochromes P450, human liver microsomes and hepatocytes. Biopharm Drug Dispos 24, 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette J. R., Brodie B. B., La Du B. N. (1957). The oxidation of drugs by liver microsomes: on the role of TPNH and oxygen. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 119, 532–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. P., Heck D. E., Mishin V., Smith P. J., Hong J. Y., Thiruchelvam M., Cory-Slechta D. A., Laskin D. L., Laskin J. D. (2007). Paraquat increases cyanide-insensitive respiration in murine lung epithelial cells by activating an NAD(P)H:paraquat oxidoreductase: identification of the enzyme as thioredoxin reductase. J Biol Chem 282, 7939–7949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P., Martin M. V., Sohl C. D., Cheng Q. (2009). Measurement of cytochrome P450 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Nat Protoc 4, 1245–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A., Paine M., Wolf C. R., Scrutton N. S., Roberts G. C. (2002). Relaxation kinetics of cytochrome P450 reductase: internal electron transfer is limited by conformational change and regulated by coenzyme binding. Biochemistry 41, 4626–4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., Zhang M., Rwere F., Waskell L., Ramamoorthy A. (2015). Kinetic and structural characterization of the interaction between the FMN binding domain of cytochrome P450 reductase and cytochrome c. J Biol Chem 290, 4843–4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalalian N., Ishikawa E. E., Silva L. F, ., Jr, , Olofsson B. (2011). Room temperature, metal-free synthesis of diaryl ethers with use of diaryliodonium salts. Org Lett 13, 1552–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban G. P., Strobel H. W. (1986). Preparation and characterization of FAD-dependent NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. J Biol Chem 261, 7824–7830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire P., Livingstone D. R. (1994). Inhibition studies on the involvement of flavoprotein reductases in menadione- and nitrofurantoin-stimulated oxyradical production by hepatic microsomes of flounder (Platichthys flesus). J Biochem Toxicol 9, 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locuson C. W., Hutzler J. M., Tracy T. S. (2007). Visible spectra of type II cytochrome P450-drug complexes: evidence that “incomplete” heme coordination is common. Drug Metab Dispos 35, 614–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majander A., Finel M., Wikstrom M. (1994). Diphenyleneiodonium inhibits reduction of iron-sulfur clusters in the mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I). J Biol Chem 269, 21037–21042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J. J., Anderson D. J., McDonald B. J., Narayanasami R., Bennett B. M. (1998). Inhibition of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase and glyceryl trinitrate biotransformation by diphenyleneiodonium sulfate. Biochem Pharmacol 56, 881–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishin V., Gray J. P., Heck D. E., Laskin D. L., Laskin J. D. (2010). Application of the Amplex red/horseradish peroxidase assay to measure hydrogen peroxide generation by recombinant microsomal enzymes. Free Radic Biol Med 48, 1485–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishin V., Heck D. E., Laskin D. L., Laskin J. D. (2014). Human recombinant cytochrome p450 enzymes display distinct hydrogen peroxide generating activities during substrate independent NADPH oxidase reactions. Toxicol Sci 141, 344–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishin V. M., Koivisto T., Lieber C. S. (1996). The determination of cytochrome P450 2E1-dependent p-nitrophenol hydroxylation by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal Biochem 233, 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modha S. G., Greaney M. F. (2015). Atom-economical transformation of diaryliodonium salts: tandem C-H and N-H arylation of indoles. J Am Chem Soc 137, 1416–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murataliev M. B., Feyereisen R., Walker F. A. (2004). Electron transfer by diflavin reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1698, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell V. B., Smith G. C, Jones O. T. (1994). Involvement of phenyl radicals in iodonium inhibition of flavoenzymes. Mol Pharmacol 46, 778–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell V. B., Tew D. G., Jones O. T, England P. J. (1993). Studies on the inhibitory mechanism of iodonium compounds with special reference to neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Biochem J 290, 41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T., Sato R. (1964). The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. I. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J Biol Chem 239, 2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter T. D. (2012). New insights into the role of cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) in microsomal redox biology. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Poulos T. L. (2005). Intermediates in P450 catalysis. Philos Trans a Math Phys Eng Sci 363, 793–806. discussion 1035-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller D. J., Wilks A., Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Poulos T. L. (1999). Crystal structure of human heme oxygenase-1. Nat Struct Biol 6, 860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen A. L., Porter T. D., Wilson T. E., Kasper C. B. (1989). Structural analysis of the FMN binding domain of NADPH-cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem 264, 7584–7589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J. D., Golden T., Guo C. J., Tu S. P., Scott P., Lee M. J., Yang C. S., Gow A. J. (2013). Tocopherol supplementation reduces NO production and pulmonary inflammatory response to bleomycin. Nitric Oxide 34, 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter P. (1960). The nature of the heme binding in microsomal cytochrome b5. J Biol Chem 235, 2492–2497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuehr D. J. (1999). Mammalian nitric oxide synthases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1411, 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuehr D. J., Fasehun O. A., Kwon N. S., Gross S. S., Gonzalez J. A., Levi R., Nathan C. F. (1991). Inhibition of macrophage and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase by diphenyleneiodonium and its analogs. Faseb J 5, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew D. G. (1993). Inhibition of cytochrome P450 reductase by the diphenyliodonium cation. Kinetic analysis and covalent modifications. Biochemistry 32, 10209–10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam P., de Toledo S. M., Pandey B. N., Tephly L. A., Carter A. B., Little J. B., Spitz D. R., Azzam E. I. (2008). Regulation of normal cell cycle progression by flavin-containing oxidases. Oncogene 27, 20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermilion J. L., Ballou D. P., Massey V. L., Coon M. J. (1981). Separate roles for FMN and FAD in catalysis by liver microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. J Biol Chem 256, 266–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermilion J. L., Coon M. J. (1978a). Identification of the high and low potential flavins of liver microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. J Biol Chem 253, 8812–8819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermilion J. L., Coon M. J. (1978b). Purified liver microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. Spectral characterization of oxidation-reduction states. J Biol Chem 253, 2694–2704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Gray J. P., Mishin V., Heck D. E., Laskin D. L., Laskin J. D. (2008). Role of cytochrome P450 reductase in nitrofurantoin-induced redox cycling and cytotoxicity. Free Radic Biol Med 44, 1169–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Gray J. P., Mishin V., Heck D. E., Laskin D. L., Laskin J. D. (2010). Distinct roles of cytochrome P450 reductase in mitomycin C redox cycling and cytotoxicity. Mol Cancer Ther 9, 1852–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Zhang R. Y., Chen S. Y., Zhang J., Yu X. Q. (2012). Direct arylation of arene and N-heteroarenes with diaryliodonium salts without the use of transition metal catalyst. J Org Chem 77, 766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K. A., Marletta M. A. (1992). Nitric oxide synthase is a cytochrome P-450 type hemoprotein. Biochemistry 31, 6627–6631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]