Abstract

The role of pathological response in long-term outcome is still unclear in cervical cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in China. This study aimed to investigate the effect of optimal pathologic response (OPR) on survival in the patients treated with NACT and radical hysterectomy. First, 853 patients with stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer were included in a retrospective analysis; a Cox proportional hazards model was used to investigate the relationship between pathological response and disease-free survival (DFS). In the retrospective database, 64 (7.5%) patients were found to have achieved an OPR (residual disease <3 mm stromal invasion); in the multivariate Cox model, the risk of death was much greater in the non-OPR group than in the OPR group (HR, 2.61; 95%CI, 1.06 to 6.45; P = 0.037). Next, the role of OPR was also evaluated in a prospective cohort of 603 patients with cervical cancer. In the prospective cohort, 56 (9.3%) patients were found to have achieved an OPR; the log-rank tests showed that the risk of recurrence was higher in the non-OPR patients than in the OPR group (P = 0.05). After combined analysis, OPR in cervical cancer was found to be an independent prognostic factor for DFS.

Cervical cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer deaths in less developed areas. It has been estimated that there were 527,600 new cervical cancer patients and 265,700 deaths around the world in 20121. In China, cervical cancer had a cancer prevalence estimates for 5 years with 313,700 cases in 20112. Concomitant chemo-radiotherapy (CCRT) is the gold standard therapy for locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC). However, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as a promising step forward in the management of cervical cancer3,4,5. As precision radiotherapy units are particularly rare in developing areas, such as in rural areas of China, doctors have to resort to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy to shrink tumours for surgical performance6,7,8,9,10,11. Quite a few studies have also investigated this innovation, including randomized clinical trials and cohort and case-control studies across the world6,7,8,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Furthermore, NACT provides an opportunity to optimize therapy, especially for fertility-preserving therapy19,20. This favourable result of NACT may lead to a new era of LACC treatment.

In addition, NACT also helps clinicians assess tumour response to a particular chemotherapeutic regimen9,10,13,21,22,23. Previous studies in western areas have concluded that an optimal pathological response (OPR) may be a prognostic factor for survival in cervical cancer12,24. However, few studies have examined the impact of OPR on survival in Chinese patients, and no studies have performed such an assessment with a sufficiently large sample size to draw a definitive conclusion.

Therefore, we designed a retrospective study to assess whether pathological response affected survival in Chinese patients with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and radical hysterectomy; additionally, we validated the effect of pathological response in a prospective cohort.

Results

Patient characteristics

In the retrospective analysis, we included 853 patients with stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer receiving neo-adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy and radical hysterectomy (Table 1). The median age of the patients at the time of study entry was 44 (range 39–50) years. Of the 853 patients, 64 (7.5%) achieved an OPR, and the other 789 did not. In the prospective cohort, 603 patients were included, all of whom underwent neo-adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy and radical hysterectomy; the details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics for all patients.

| Characteristics |

Retrospective study(n = 853) |

Prospective cohort study(n = 603) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age(25th–75th percentiles) (year) | ||||

| Median | 44 | 45 | ||

| Range | 39–50 | 41–51 | ||

| Age (year) | ||||

| 20–30 | 36 | 4.2 | 18 | 3.0 |

| 30–40 | 218 | 25.6 | 126 | 20.9 |

| 40–50 | 403 | 47.2 | 306 | 50.6 |

| 50–60 | 165 | 19.3 | 131 | 21.6 |

| 60–70 | 31 | 3.6 | 22 | 3.6 |

| Tumor size(25th–75th percentiles) (cm) | ||||

| Median | 4.0 | 4.0 | ||

| Range | 3.5–5.0 | 3.0–5.0 | ||

| Tumor grade | ||||

| G1 | 58 | 6.8 | 42 | 7.0 |

| G2 | 354 | 41.5 | 242 | 40.1 |

| G3 | 240 | 28.1 | 185 | 30.7 |

| Undetermined | 201 | 23.6 | 134 | 22.2 |

| FIGO stage | ||||

| IB2 | 220 | 25.8 | 134 | 22.2 |

| IIA | 265 | 31.1 | 129 | 21.4 |

| IIB | 368 | 43.1 | 340 | 56.4 |

| Cell type | ||||

| Squamous | 756 | 88.6 | 533 | 88.4 |

| Non-squamous | 91 | 10.7 | 60 | 10.0 |

| Unknown | 6 | 0.7 | 10 | 1.6 |

| Pathological response | ||||

| OPR | 64 | 7.5 | 56 | 9.3 |

| non-OPR | 789 | 92.5 | 542 | 89.9 |

| Unknown | 5 | 0.8 | ||

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards model for DFS

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to investigate whether clinical variables and pathological response affected the DFS. In the univariate Cox analysis of the retrospective study, pathological response achieved statistical significance for the DFS (HR 11.05, P = 0.02 in Table 2, respectively). For the prospective cohort study, the pathological response also achieved statistical significance for the DFS (HR 3.65, P = 0.07 in Table 3).

Table 2. Univariate Cox regression for DFS in the retrospective study.

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological response | OPR VS Non-OPR | 11.05 | 1.54 to 79.45 | 0.02 |

| Age | >44 VS ≤44 years | 1.61 | 1.05 to 2.48 | 0.03 |

| Stage | IIA VS IB2 | 2.18 | 1.13 to 4.20 | 0.02 |

| IIB2 VS IB2 | 2.44 | 1.33 to 4.48 | 0.004 | |

| Tumor size | >4 cm VS ≤4 cm | 1.37 | 0.86 to 2.19 | 0.19 |

| Grade | G2 VS G1 | 2.16 | 0.67 to 7.01 | 0.20 |

| G3 VS G1 | 3.38 | 1.06 to 10.81 | 0.04 | |

| Undetermined VS G1 | 2.05 | 0.60 to 6.97 | 0.25 | |

| Cell type | Squamous VS non-squamous | 2.24 | 1.32 to 3.82 | 0.003 |

| LVSI | Positive VS negative | 1.40 | 0.75 to 2.61 | 0.29 |

| Parametrial infiltration | Positive VS negative | 2.61 | 1.53 to 4.44 | <0.001 |

| Vaginal surgical margin | Positive VS negative | 1.91 | 0.83 to 4.41 | 0.13 |

| Lymph node metastasis | Positive VS negative | 3.68 | 2.21 to 6.12 | <0.001 |

LVSI, Lymph vascular space invasion. DFS, disease free survival.

Table 3. Univariate Cox regression for DFS in the prospective study.

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological response | OPR VS Non-OPR | 3.65 | 0.89 to 14.92 | 0.07 |

| Age | >44 VS ≤44 years | 2.18 | 1.30 to 3.67 | 0.003 |

| Stage | IIA VS IB2 | 1.61 | 0.64 to 4.09 | 0.31 |

| IIB2 VS IB2 | 2.56 | 1.20 to 5.43 | 0.01 | |

| Tumor size | >4 cm VS ≤4 cm | 0.93 | 0.56 to 11.57 | 0.23 |

| Grade | G2 VS G1 | 1.30 | 0.39 to 4.36 | 0.69 |

| G3 VS G1 | 1.94 | 0.58 to 6.55 | 0.28 | |

| Undetermined VS G1 | 2.40 | 0.70 to 8.20 | 0.16 | |

| Cell type | Squamous VS non-squamous | 1.45 | 0.68 to 3.12 | 0.34 |

| LVSI | Positive VS negative | 2.48 | 0.92 to 6.68 | 0.07 |

| Parametrial infiltration | Positive VS negative | 3.32 | 1.20 to 9.16 | 0.02 |

| Vaginal surgical margin | Positive VS negative | 4.04 | 1.71 to 9.54 | 0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | Positive VS negative | 2.62 | 1.44 to 4.78 | 0.002 |

LVSI, Lymph vascular space invasion; DFS, disease free survival.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for DFS

In the multivariate analysis of the retrospective cohort, we observed that pathological response was associated with the DFS rate (HR 2.61, P = 0.037 in Table 4). In the prospective cohort study, the pathological response also achieved higher DFS result but without statistical significance (HR 4.03, P = 0.053 in Table 5).

Table 4. Multivariate Cox regression for DFS in the retrospective study.

| Variables |

Retrospective study |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | HR(95% CI) | P | ||

| Pathological response | ||||

| OPR | 1 | |||

| Non-OPR | 0.96 | 2.61(1.06,6.45) | 0.037 | |

| FIGO stage | ||||

| IB2 | 1 | |||

| IIA | 0.60 | 1.81(1.19,2.78) | 0.006 | |

| IIB | 0.44 | 1.55(1.03,2.34) | 0.038 | |

| Grade | ||||

| G1 | 1 | |||

| G2 | 0.50 | 1.61(0.77,3.38) | 0.20 | |

| G3 | 1.11 | 3.05(1.46,6.34) | 0.003 | |

| Undetermined | 0.22 | 1.24(0.56,2.75) | 0.60 | |

| Cell type | ||||

| Squamous | 1 | |||

| Non-squamous | 0.56 | 1.76(1.18,2.61) | 0.005 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| Negative | 1 | |||

| Positive | 0.58 | 1.78(1.30,2.42) | <0.001 | |

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; DFS, disease free survival.

Table 5. Multivariate Cox regression for DFS in the prospective study.

| Variables |

Prospective cohort study |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | HR(95% CI) | P | ||

| Pathological response | ||||

| OPR | 1 | |||

| Non-OPR | 1.39 | 4.03(0.98,16.52) | 0.053 | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤44 years | 1 | |||

| >44 | 0.89 | 2.43(1.44,4.13) | 0.001 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| Negative | 1 | |||

| Positive | 0.43 | 1.54(1.01,2.36) | 0.045 | |

DFS, disease free survival.

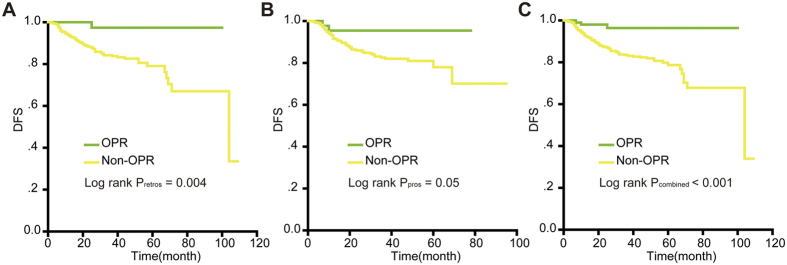

Log-rank test for DFS in the retrospective study and in the prospective cohort

DFS rates were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method for the OPR and non-OPR groups; the P values for DFS were 0.004 in the retrospective study (Fig. 1A). Later, information from the cervical cancer patients in the prospective cohort was used to assess the role of OPR in DFS (P = 0.05, Fig. 1B). Figure 1C showed when the retrospective study and the prospective study were combined, OPR patients achieved a significantly higher survival rate than non-OPR patients (P < 0.001 for DFS).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for OPR and Non-OPR patients with cervical cancer from the retrospective study, the prospective cohort and the combination of the two studies.

Disease-free survival (DFS) curves of evaluated patients in the retrospective study (A), the prospective cohort (B) and the combined results (C). Log-rank test used to calculate P values. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

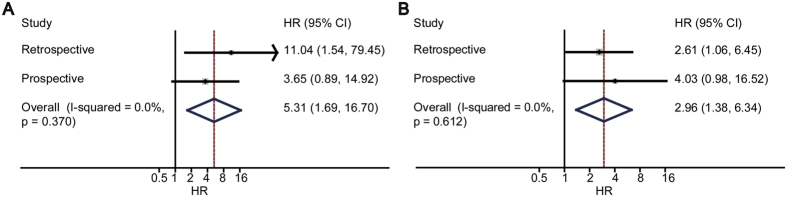

Joint analysis of the retrospective study and the prospective cohort

The results from the retrospective study and the prospective study were combined together according to the method illustrated in the previous study25. In univariate Cox analysis, HR got a value of 5.31 (95% CI, 1.69 to 16.70) (Fig. 2A). In multivariate Cox analysis, HR got a value of 2.96 (95% CI, 1.38 to 6.34) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The combined results of Non-OPR and cancer-recurrence risk.

For univariate Cox regression, the summary relative risk was 5.31 (95% CI, 1.69 to 16.70) and test of heterogeneity I2 = 0% (P = 0.37) (A); for multivariate Cox regression, the summary relative risk was 2.96 (95% CI, 1.38 to 6.34) and test of heterogeneity I2 = 0% (P = 0.61) (B). The combined analysis showed that Non-OPR was statistically associated with recurrence.

Discussion

We combined both a retrospective study and a prospective cohort to assess the value of pathological response; this study comprehensively examined the pathological response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and evaluated its value in predicting long-term disease-free survival.

When analysed using a univariate Cox proportional hazards model, our retrospective data indicated that one of the most important predictors of long-term prognosis was the invasion depth of residual cancer cells upon the completion of treatment. The condition of ≤3 mm of invasive tumour (OPR) in the cervix was demonstrated to be related to improved survival. Patients who achieved OPR exhibited excellent survival, and patients without OPR after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated significantly shorter DFS times. This effect resulted in an increase in the 3-year DFS rate. From the multivariate analysis, OPR was also found to serve as an independent prognostic factor with a high HR. The HR was similar to that of a previous study12. The combined results of the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test indicated that the OPR group demonstrated significantly improved DFS rate. For further assessment of the pathological response in cervical cancer, the results of a clinical trial should be sufficiently discussed12. The clinical trial also proved that OPR was an independent prognostic factor of survival12. The trial demonstrated a significant OS benefit at 5 years for patients experiencing an OPR versus patients who did not experience an OPR. The average death rates were significantly higher in the group that did not achieve an OPR than in the group that did achieve an OPR. A previous study also suggested that obtaining an OPR was a beneficial prognostic factor of long-term survival24,26. Other research studies, both prospective and retrospective, have also demonstrated complete or optimal partial pathologic response after neo-adjuvant systemic treatment to be associated with a higher chance of cervical cancer survival27,28. The OPR rate in our study was relatively lower than those of previous studies; this was mainly attributed to the fact that the majority of patients only received one cycle, and thus these patients may not have had the chance to respond.

A growing number of studies have also evaluated the relationship between pathological response and other malignant disease outcomes. Furthermore, pathological response has been increasingly adopted as a measure of activity for NACT and also as a prognostic factor for survival, such as in breast cancer studies. The researchers of a triple-negative breast cancer study observed that patients with a pathological complete response (PCR) demonstrated excellent survival compared with patients without a PCR29. Other researchers have noted that PCR could be used as an early surrogate marker for long-term survival in invasive breast cancer after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy30. Moreover, a group of researchers performed a meta-analysis of PCR associated with colon cancer outcomes and reported that patients with a PCR after chemoradiation demonstrated better long-term outcomes than those without a PCR in colon cancer31. Numerous results in the literature thus suggest that pathological response can affect the outcome of survival30,31,32. Researchers have also suggested that a PCR might be indicative of a prognostically favourable biological profile with fewer propensities for local or distant recurrence and improved survival. Other researchers have observed that a complete or optimal pathological response is associated with good survival outcomes27,33.

Therefore, OPR may serve as a useful prognostic indicator for cervical cancer patients who receive neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. The aim of systemic chemotherapy is to eliminate the primary tumour and to eradicate residual occult distant metastasis to ultimately improve DFS and OS. Theoretically, if an OPR is reflective of chemotherapy sensitivity in occult distant sites, patients who exhibit an OPR in their primary tumour would demonstrate the highest DFS rate. This relationship has been demonstrated in our study, as OPR was associated with a better pathological outcome.

The study included an adequate sample size for the main outcomes. However, there were some limitations. First, our study did not integrate biologic makers associated with cancer progression and survival; we considered only certain clinical factors. No biological markers were included on the gene, mRNA or protein level. Second, new surgeries, such as radical trachelectomy, should also be carefully investigated in our medical centre. To address these problems, biomarkers should be added to our studies in the future, and at the same time, new updates should be made to our database.

As is widely known, NACT may lead to excellent survival in a particular group of patients, such as the group of patients with OPR. For patients with obvious node positive disease, NACT may place them at a high risk for delaying optimal treatment. The standard treatment of LACC is chemo-radiation (CCRT), and CCRT has also shown superior outcomes in long-term survival. Therefore, doctors should perform thorough pre-treatment evaluations to identify the most suitable patients, such as OPR patients. As for the patients who are less likely to achieve OPR or clinical response after NACT, CCRT may be the appropriate therapy to pursue without exposing them to delayed therapy, such as NACT. To identify OPR patients, clinicians in our department are trying to develop a predictive model that is able to identify the patients who are most likely to achieve OPR, clinical response or non-response.

Last but not least, clinicians and scientists should pay close attention to patients who do not achieve OPR after NACT. These patients are less sensitive to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, and adjuvant post-surgery treatment such as CCRT should be particularly considered. The clinical-pathologic risk factors such as positive lymph nodes, low-grade differentiation, and parametrial infiltration, as well as GOG score should be reviewed together to make a decision on adjuvant post-surgery treatment34.

With the aim of identifying the pathological predictors of long-term survival and postoperative management effects, we conducted a research study and demonstrated that OPR is a predictor of a good prognosis. The results revealed that OPR after neoadjuvant chemotherapy can improve long-term outcomes, with fewer possibilities of recurrence, and can increase long-term survival compared with patients without an OPR. To obtain further evidence, additional prospective studies in different nations are necessary, and a model to predict OPR or clinical response is also necessary.

Methods

Study Design

First, medical records were retrospectively reviewed from a database on cervical cancer, which consisted of clinical data from 853 patients. Then, medical information was reviewed from a prospective cohort, which consisted of recently updated clinical data (http://clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01628757); 603 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria after exclusion. The following data were retrieved from the database, patient files, and pathology reports: age at diagnosis, year of treatment, stage of disease, cell type, grade of differentiation, tumour size, lymph node involvement, parametrial involvement, depth of tumour invasion, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), surgical margin status, adjuvant treatment, and follow-up status.

This study followed the declaration of Helsinki and was conducted in accordance with the approved guidelines. All experimental protocols were approved by the ethical committee of Tongji Medical College at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. All eligible patients provided written informed consent before entering this study.

Inclusion criteria

We enrolled patients based on the following criteria: 1. patients with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer; 2. patients less than 70 years old; 3. patients treated with NACT followed by radical hysterectomy; and 4. patients not receiving primary radiotherapy, concurrent chemo-radiotherapy or preoperative radiotherapy and those without complicating disease including renal failure and hepatic failure or prior malignant disease. Surgery was performed within 4 weeks of completing the last course of chemotherapy. All patients received radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy, and para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed in patients with suspicious para-aortic lymph node metastasis.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria included a Karnofsky Performance Status <70, age less than 18 years old, previous history of cancer, or previous treatment of cancer (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy). Patients with active infectious disease or other medical complications including hepatic failure and renal failure and women who lacked information on clinical risk factors were also excluded from this study.

Pretreatment and post-treatment evaluation

The diagnosis was confirmed by pathological experts for each patient according to cervical biopsy and staged as IB to IIB by clinicians according to the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). Tumour status was checked clinically, and EKG was performed when each treatment began. An ultrasound of the tumour and pelvic condition was scheduled after each cycle to control for progressive disease in all patients. If the tumours were considered operable, radical surgery was performed within 4 weeks of completion of the last scheduled chemotherapy cycle. Otherwise, the patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

The standard treatment for NACT is a platinum-based regimen, which was used in our study. NACT was administered in 1–2 courses, depending on the patient’s tolerance and response, and a small number of patients received an additional 1–2 cycles.

Pathological response

The pathological response was retrospectively assessed as in previous studies3,12,24,26; PCR was defined as the complete disappearance of the tumour from the cervix and negative nodes; PR1, partial response one, was defined as residual disease with less than 3 mm stromal invasion, including in situ carcinoma with or without lymphatic metastasis; and PR2, partial response two, was defined as persistent residual disease with more than 3 mm stromal invasion in the surgical specimen. Studies chose 3 mm as the lowest limit of OPR because it represents the maximal extension of FIGO stage IA1 cervical cancer12,32. OPR was defined as PCR+PR1. The histopathological diagnosis was confirmed by two pathologists for each patient in our study. In addition, the assessment of OPR was based on the histopathological diagnosis. In our study, we investigated the influence of OPR on survival.

Follow-up study

The follow-up of patients was designed to be conducted every 3 months in the first year and every 6 months in the next four years after surgery. According to our database, for a small proportion of patients, follow-up was not performed due to loss of contact, and the data from these individuals were excluded from the survival analysis. The DFS rate was calculated from the day of diagnosis until the date of first relapse or death (regardless of any cause)35.

Statistical analysis

The primary goal for this analysis was the relationship between response and DFS. When testing at the 0.05 level (two-sided test), the combined sample size (both the retrospective study and prospective cohort) would provide a statistical power more than 90% to detect the statistical difference for DFS with the hypothesis (HR = 2.5).

Log-rank tests were used for the DFS comparisons. A Cox proportional hazards model was used for multiple regression analysis to verify whether the clinical variables and the pathological response variable predicted DFS. In the multivariate models, variables were automatically retained by the computer if their associated multivariate P values were less than 0.05 or if they were necessary for the model. The median follow-up time was calculated as the median observation time among all patients. IBM SPSS 20.0 software was used to perform the statistical analyses. All reported P-values were two-sided, and we considered P < 0.05 to be significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Huang, K. et al. Optimal pathological response indicated better long-term outcome among patients with stage IB2 to IIB cervical cancer submitted to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci. Rep. 6, 28278; doi: 10.1038/srep28278 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the grant from International S&T Cooperation Program of China (No. 2013DFA31400), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NO. NECT-12-0646), the National Science-technology Support Plan Projects 2015BAI13B05, Ministry of health industry fund WSBHYJJ20110012-3, Science and Technology Planning Project of Hubei Province 2012FFB02509, the Foundation of China (973 Program; No. 2009CB521808; 2015CB553903) and by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81300460; 81402160; 81302267; 81370469; 81302264; 81201639; 81300453; 81072132; 81372781; 81071663; 81370469; 81230038; 81230052; 81172467; 81402161; 81403166; 30973472; 81001151; 81071663; 30973205; 30973184; 81172464; 81101964) and National Major Science and Technology Project (No. 2009ZX09103-739). We thank the professors in Wuhan University, the professors in Zhejiang University, and the scholars in Iwate Medical University. We also thank Hui Xing, Shaoshuai Wang, Yao Jia, Fangxu Tang, Hang Zhou, Jin Zhou for their useful help.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conception, hypothesis delineation and study design: K.H., H.S., Z.C, S.L. and S.W.; data acquisition, analysis and interpretation: K.H., H.S., Z.C, X.L., S.S.W., X.Z., F.T., Y.J., T.H., X.D, H.W., Z.L., J.H., J.G., X.W., S.Z., L.W., J.Z., L.G., R.Y., J.S. and Q.Z.; writing first the draft of manuscript: K.H., H.S., Z.C, S.L. and S.W.; revision of manuscript: all authors.

References

- Torre L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65, 87–108 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng R., Zeng H., Zhang S., Chen T. & Chen W. National estimates of cancer prevalence in China, 2011. Cancer Lett 370, 33–38 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minig L. et al. Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery for cervical carcinoma international federation of gynecology and obstetrics stage IB2-IIB. Int J Gynecol Cancer 23, 1647–1654 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himoto Y. et al. Assessment of the early predictive power of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging parameters during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for uterine cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24, 751–757 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso D. et al. Phase II trial on cisplatin-adriamycin-paclitaxel combination as neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24, 729–734 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. et al. The efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer: A randomized multicenter study. Gynecol Oncol , 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.06.027 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. Prognostic value of responsiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery for patients with stage IB(2)/IIA(2) cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 128, 524–529 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Liang L. Z., Cao L. P., Min Z. & Liu J. H. Clinical effects of irinotecan hydrochloride in combination with cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 123, 99–104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Liang C., Zhang L., Huang S. & Wu X. Clinical efficacy of modified preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced (stage IB2 to IIB) cervical cancer: randomized study. Gynecol Oncol 110, 308–315 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T. et al. Matched-case comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with FIGO stage IB1-IIB cervical cancer to establish selection criteria. Eur J Cancer 48, 2353–2360 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H. B., Chen H. Z. & Yin H. H. Randomized study of preoperative chemotherapy versus primary surgery for stage IB cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 32, 315–323 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buda A. et al. Randomized trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy comparing paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin with ifosfamide and cisplatin followed by radical surgery in patients with locally advanced squamous cell cervical carcinoma: the SNAP01 (Studio Neo-Adjuvante Portio) Italian Collaborative Study. J Clin Oncol 23, 4137–4145 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti-Panici P. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical surgery versus exclusive radiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell cervical cancer: results from the Italian multicenter randomized study. J Clin Oncol 20, 179–188 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T. C. et al. Randomized trial of neoadjuvant cisplatin, vincristine, bleomycin, and radical hysterectomy versus radiation therapy for bulky stage IB and IIA cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol 18, 1740–1747 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi J. et al. Results of a prospective randomized trial with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in stage IB, bulky, squamous carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol 49, 156–165 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy using platinum- and taxane-based regimens for bulky stage Ib2 to IIb non-squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 71, 657–662 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T. et al. Phase II study of tri-weekly cisplatin and irinotecan as neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. Oncol Lett 1, 515–519 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T. et al. Results of neoadjuvant chemotherapy using tri-weekly CDDP/CPT-11 for locally advanced cervical cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 37, 643–648 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice P., Uzan C., Gouy S., Verschraegen C. & Haie-Meder C. Gynaecological cancers in pregnancy. Lancet 379, 558–569 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rob L., Skapa P. & Robova H. Fertility-sparing surgery in patients with cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol 12, 192–200 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S. et al. Matched-case comparison for the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery in FIGO stage IB1-IIA cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 119, 217–224 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio H. et al. Abdominal radical trachelectomy as a fertility-sparing procedure in women with early-stage cervical cancer in a series of 61 women. Gynecol Oncol 115, 51–55 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi J., Sananes C., Giaroli A., Maya G. & di Paola G. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Gynecol Oncol 38, 486–493 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo N. G. A. & Lissoni A. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in locally advanced uterine cervical cancer (LAUCC): Correlation between pathological response and survival. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 17, 352a (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Tierney J. F., Stewart L. A., Ghersi D., Burdett S. & Sydes M. R. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 8, 16 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buda A. et al. Long-Term Clinical Benefits of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Women With Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: Validity of Pathological Response as Surrogate Endpoint of Survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer , 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000515 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubamoto H. et al. Prognostic factors for locally advanced cervical cancer treated with neoadjuvant intravenous and transuterine arterial chemotherapy followed by radical hysterectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 23, 1470–1475 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. W. et al. Is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery more effective than radiation therapy for stage IIB cervical cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer 23, 1303–1310 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke C. et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 26, 1275–1281 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazouni C. et al. Residual ductal carcinoma in situ in patients with complete eradication of invasive breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not adversely affect patient outcome. J Clin Oncol 25, 2650–2655 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas M. et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 11, 835–844 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadducci A. et al. Pathological response on surgical samples is an independent prognostic variable for patients with Stage Ib2-IIb cervical cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical hysterectomy: an Italian multicenter retrospective study (CTF Study). Gynecol Oncol 131, 640–644 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Minckwitz G. et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 30, 1796–1804 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado G. et al. Prospective surgical-pathological study of disease-free interval in patients with stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 38, 352–357 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieras V. et al. Randomized parallel study of doxorubicin plus paclitaxel and doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide as neoadjuvant treatment of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 22, 4958–4965 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]