Abstract

Arabidopsis MPK4 and MPK6 are implicated in different signalling pathways responding to diverse external stimuli. This was recently correlated with transcriptomic profiles of Arabidopsis mpk4 and mpk6 mutants, and thus it should be reflected also on the level of constitutive proteomes. Therefore, we performed a shot gun comparative proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis mpk4 and mpk6 mutant roots. We have used bioinformatic tools and propose several new proteins as putative MPK4 and MPK6 phosphorylation targets. Among these proteins in the mpk6 mutant were important modulators of development such as CDC48A and phospholipase D alpha 1. In the case of the mpk4 mutant transcriptional reprogramming might be mediated by phosphorylation and change in the abundance of mRNA decapping complex VCS. Further comparison of mpk4 and mpk6 root differential proteomes showed differences in the composition and regulation of defense related proteins. The mpk4 mutant showed altered abundances of antioxidant proteins. The examination of catalase activity in response to oxidative stress revealed that this enzyme might be preferentially regulated by MPK4. Finally, we proposed developmentally important proteins as either directly or indirectly regulated by MPK4 and MPK6. These proteins contribute to known phenotypic defects in the mpk4 and mpk6 mutants.

MAPKs are important signalling molecules which are involved in transduction of signal derived from many environmental and developmental stimuli1. MAPK signalling results in gene activation triggering appropriate defense responses or in the activation or repression of developmentally-regulated proteins modulating plant growth and development2. The complete sequencing and annotation of the Arabidopsis genome resulted in the identification of 20 MAPK-encoding genes, while MPK4, MPK6 and MPK3 are the most studied ones and they play dominant roles in the transduction of stress and developmental signal as well as in the cross-talk with other signaling pathways2.

MPK4 and MPK6 are commonly activated by cold and salt stress downstream of MEKK1 (MAP3K) and MKK2 (MAP2K) in Arabidopsis3, while MPK4 via this pathway also negatively regulates salicylic acid (SA) and ROS production4. MEKK1-mediated activation of MPK6 (together with MPK3) was reported also via MKK4/MKK5 in the response to bacterial elicitor flagellin. This signaling cascade affects expression of defense related genes5. The MKK4-MPK6 module also phosphorylates and activates ACC synthases ACS2 and ACS6 which are key enzymes for ethylene synthesis6. Additionally, MPK6 is specifically activated by MKK3 in response to jasmonic acid (JA) and negatively regulates the JA signalling pathway7. MPK6 is also activated by the pathway that includes ANP1 (MAP3K)–MKK4/MKK5 upon hydrogen peroxide treatment8. In contrary, MPK4 is activated by MEKK1 (MAP3K)–MKK2 (MAP2K) pathway under oxidative stress9.

Along with roles of MPK4 and MPK6 in various stress responses, they are involved in multiple developmental processes. Thus, MPK6 is involved in embryogenesis10, stomata formation11, cell division plane orientation and root development12 and it is localized in the secretory Trans-Golgi network (TGN) vesicles and plasma membrane. MPK4 controls cell division, root growth and formation of root hairs13,14.

An absence of particular members of the MAPK cascade in Arabidopsis single and double knockout mutants can lead to considerable molecular, physiological, developmental and phenotypic changes, and it can modify their stress responses3,10. However, there is only very scarce information about the proteome wide effects resulting from genetically-affected MAPK signaling in plants15.

Roots of mpk4 mutant have altered organization of cortical microtubules leading to radial root expansion and adverse effects on root hair morphogenesis13. At the subcellular level, the mpk4 mutant showed aberrant spindle and phragmoplast formation and drastically delayed or abortive mitosis and cytokinesis14. Additionally, hydrogen peroxide accumulation, reduced expression of auxin inducible marker genes and elevated levels of mRNA encoding stress response proteins was observed in the seedlings of mpk4 mutant4. Detailed analyses of mpk6 knock-out mutants showed root phenotypes, which are consequences of ectopic cell divisions and aberrant orientation of cell division, resulting in disordered root cell files in the mpk6 mutants12. Here, we have studied major changes associated with MPK4 and MPK6 deficiency in Arabidopsis roots on the proteome level. We aimed to find protein candidates contributing to specific root phenotypic features of mpk4 and mpk6 mutants. In addition, we also focused on proteome changes associated with oxidative stress and defense responses in these two mutants.

Results

Overview of root proteomes of Arabidopsis mpk4 and mpk6 mutants

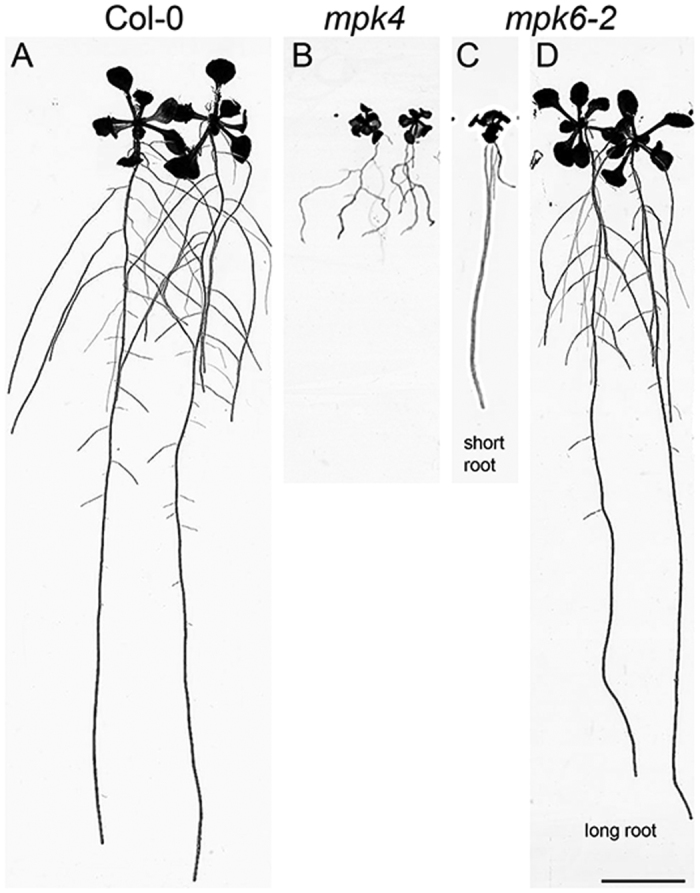

We performed proteomic analyses of mpk4 and mpk6 mutant roots in direct comparison to the Col-0 wild type. Representative pictures of analyzed mutants are provided in Fig. 1. This shot gun MS/MS-based proteomic analysis identified in average 437 proteins in the mpk4 and 444 proteins in the mpk6 mutant. All proteins with statistically significant changes in their abundances between wild type and mutant plants were selected using one-way Anova test. They are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Figure 1.

Representative pictures of 14 days old wild type plants Col-0 (A), mpk4 (B) and mpk6-2 short (C) and long root (D) mutants used for proteomic and biochemical analyses. Bar: 1 cm.

First, we compared the numbers of differentially regulated proteins in both mutants (Supplementary Table S3). Only proteins with change higher than 1.5 fold were considered in this study. We detected 63 differentially abundant proteins in the mpk4 mutant when compared to Col-0 wild type seedlings, while there were 32 differentially abundant proteins in the mpk6 mutant. In addition, several proteins (33 and 19 for mpk4 and mpk6, respectively) were detected only in one sample, either in the wild type, or in the one of the mutants, indicating that in such cases their abundance was below the detection sensitivity limit. Altogether, we have found 96 and 51 differentially abundant proteins in the roots of mpk4 and mpk6 mutants, respectively. These data might indicate that MPK4 deficiency has broader influence on Arabidopsis basal root proteome as compared to MPK6.

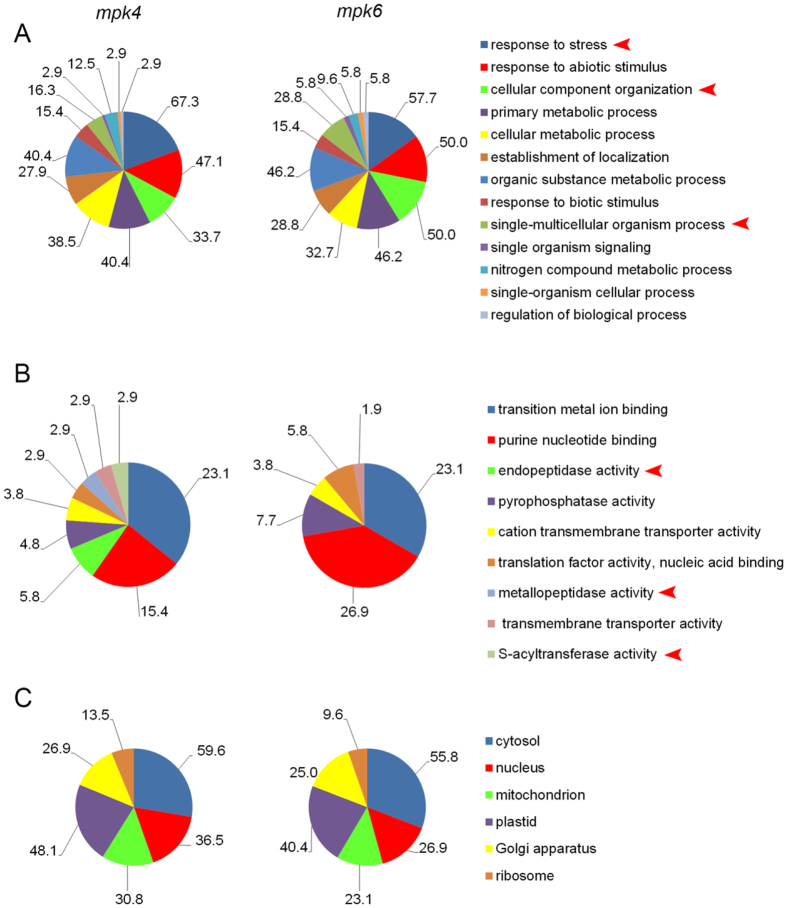

In order to functionally classify these proteins in differential proteomes of both mutants, we performed analyses of known and predicted functional protein association networks using STRING16 (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2) and gene ontology (GO) annotation according to biological process, molecular function and cellular compartment using Blast2Go17 software (Fig. 2A–C). These analyses revealed that mpk4 and mpk6 mutants did not substantially differ in the number of GO annotations detected in differential proteomes according to biological function at the 3rd level of ontology (Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, some interesting differences, including different number of proteins in the two mutants, have been found in GO annotations in terms of response to stress, cellular component organization and single multicellular organism process (Fig. 2A) as well as in terms of molecular functions (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, no changes were detected in GO annotations in terms of subcellular localization (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Comparison of gene ontology classification (at 3rd level) of mpk4 and mpk6 mutant root differential proteomes according to (A) biological process, (B) molecular function, (C) cellular compartment. Arrowheads indicate most prominent differences between the mutants.

We also performed a GO annotation analysis on whole proteomes of mpk4 and mpk6 roots (Supplementary Figs S3–S5). In this case, only minor differences were observed between whole proteomes of the mutants.

Next, we searched for proteins which abundances were commonly changed in both mutants compared to wild type (Supplementary Table S4). Eight differentially abundant proteins were detected in both mpk4 and mpk6 roots. Two of them showed decreased abundance in both mutants (arabinogalactan protein 31 and profilin 2) and three other proteins had increased abundance in both mutants (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, TRAF-like family protein and translational initiation factor 4A-1). These small numbers of commonly regulated proteins show that root proteomes of the mutants are quite different.

Does MPK3 compensate for missing MPK6 in roots of the mpk6 mutant?

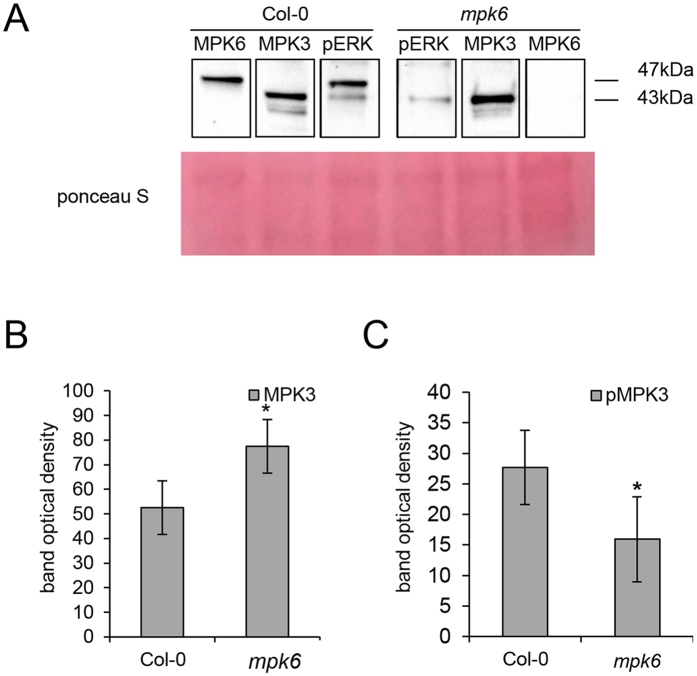

MPK3 and MPK6 show high level of functional redundancy in response to external stimuli8 and in regulating plant development18. It was also found that MPK3 activities might be increased in mpk6 mutants in response to various external stimuli. In this study, we evaluated the MPK3 abundance and activity in the roots of the mpk6 untreated mutant using affinity purified antibodies against MPK3 and phosphorylated mammalian ERK1/2 (phospho-p44/42, pERK) recognizing pTEpY-dual phosphorylation motif (Fig. 3), preferentially in MPK6 and MPK3. We detected increased abundance of MPK3 in the mpk6 mutant as compared to the Col-0 wild type (Fig. 3A,B). By using pERK antibody we detected two bands in Col-0 wild type roots, corresponding to phosphorylated MPK6 and MPK3, respectively. As expected, mpk6 mutant showed only a single band, corresponding to the activated MPK3 which was, however, less prominent in the mutant as compared to the Col-0 wild type (Fig. 3A,C). These data suggest that differences in the root proteome composition of the mpk6 mutant might be, at least partially, attributed also to the higher abundance but lower activity of MPK3 in the roots of this mutant.

Figure 3. Imunoblotting analysis of MPK3 activity in the mpk6 mutant using phospho-specific pERK antibody.

(A) Representative immunoblots of wild type and mpk6 mutant roots probed with anti-MPK3 (lane MPK3), anti-MPK6 (lane MPK6) and anti-phospho-p44/42 (pERK) antibodies. (B) Quantification of the band optical density corresponding to MPK3 in (A). (C) Quantification of the band optical density corresponding to phosphorylated MPK3 (pMPK3) (band of 43 kDa in lane pERK in A) in wild type and mpk6 mutant roots. Error bars are standard deviations calculated from 3 biological replicates. Stars indicate significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 according to Student t-test.

Prediction of putative MPK4 and MPK6 targets

Proteomic analyses performed on the loss-of-function and knockout mutants can help to identify both direct and indirect targets of MAPKs. The interaction of MAPKs with their direct protein targets is conditioned by the presence of MAPK docking site, MAPK-specific phosphorylation site and common subcellular localization with MAPKs. Therefore, we analyzed proteomically-identified proteins of mpk4 and mpk6 mutant roots for such motifs and gained information about localization of these putative target proteins. Proteins containing both docking and phosphorylation motifs are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Details of prediction including probabilities, scores, putative phosphorylation sites and amino acid sequences of the docking domains are provided in Supplementary Tables S5–S8. We have found 17 and 8 putative target proteins in the mpk4 and mpk6 mutants, respectively. The localization of some putative target proteins corresponded with the published localization of MPK4 and MPK6 in Arabidopsis12,14,19. These were for example elongation factor EF-2, uncharacterized protein (gi:240254562) and mRNA decapping complex VCS in the mpk4 mutant as well as CDC48A and phospholipase D alpha 1 in the mpk6 mutant, while heat shock protein 70–3 was found in both mutants.

Table 1. List of differentially regulated proteins containing both MAPK-specific phosphorylation site and MAPK docking site as predicted by GPS 3.0 software and Eukaryotic Linear Motif Resource (http://elm.eu.org/index.html) in the roots of the mpk4 mutant.

| Accesion number | Protein name | Phosphopeptide sequences | Docking sequence | Fold change | Cell compartment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gi|145324054 | arabinogalactan protein 31 | EVNHKTQTPSLAPAP | KFNRSLVAV, 180–188 [A] | unique in wild type | cell wall72 |

| HPHPPAKSPVKPPVK | KKLGKSTVVV, 285–294 [A] | ||||

| PPVKAPVSPPAKPPV | KLGKSTVVV, 286–294 [A] | ||||

| PPVKPPVSPPAKPPV | |||||

| APVKPPVSPPTKPPV | |||||

| PPTKPPVTPPVYPPK | |||||

| gi|15226573 | Ferredoxin–nitrite reductase | SFSLTFTSPLLPSSS | KPKRSVLV, 19–26 [A] | unique in wild type | plastid (prediction) |

| KIEREPMKL, 74–82 [A] | |||||

| KSSKDDIDVRL, 103–113 [A] | |||||

| RKWNVCV, 246–252 [A] | |||||

| KDGRFGFNLLV, 274–284 [A] | |||||

| KRCEEAIPL, 291–299 [A] | |||||

| RQKTRMMWL, 328–336 [A] | |||||

| KKGVRVTELVPL, 554–565 [A] | |||||

| KGVRVTELVPL, 555–565 [A] | |||||

| gi|15233349 | aconitate hydratase 1 | RATIANMSPEYGATM | RIDKLPYSIRI, 35–45 [A] | unique in wild type | cytosol, mitochondria73 |

| YFKGMTMSPPGPHGV | KRPHDRVPL, 378–386 [A] | ||||

| KKACDLGL, 458–465 [A] | |||||

| gi|18400212 | dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase, long form protein | TTSTKLSSPMAGPKL | RRDHAVAV, 20–27 [A] | unique in wild type | mitochondria74 |

| EIGMPSLSPTMTEGN | |||||

| gi|22331076 | Subtilase family protein | PLLLCFFSPSSSSSD | RRHPSVISV, 93–101 [A] | unique in wild type | extracellular (prediction) |

| LLRSLPSSPQPATLL | |||||

| HGFSARLSPIQTAAL | |||||

| REIHTTHTPAFLGFS | |||||

| LGTLIGPSPPSPRVA | |||||

| LIGPSPPSPRVAAFS | |||||

| ANVEIDVSPSKLAFS | |||||

| gi|240254562 | uncharacterized protein | SSSGNVTTPTQTAST | KSRDIDLSF, 1264–1272 [A] | unique in wild type | nucleus (prediction) |

| gi|30682607 | mRNA decapping complex VCS | PGISAQPSPVTQQQQ | RKAQPLVVL, 352–360 [A] | unique in wild type | cytoplasmic foci75 |

| TPPLNLQSPRSNHNP | KESKRLEVAL, 918–927 [A] | ||||

| TLPQLPLSPRLSSKL | KRLEVAL, 921–927 [A] | ||||

| gi|15232845 | probable mitochondrial-processing peptidase subunit beta | DSVPASASPTALSPP | RRSQRRLFL, 11–19 [A] | 13.11 | mitochondria |

| SASPTALSPPPPHLM | RINRERDVIL, 210–219 [A] | ||||

| gi|15221019 | GDSL esterase/lipase | ITVAGQNSPVVALFT | extracellular (prediction) | ||

| KFSDGLITPDFLAKF | KFMKIPLAI, 88–96 [A] | 5.48 | |||

| REFWVPPTPATVHAS | |||||

| gi|15232603 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0-2 | KGTVEIITPVELIKQ | RKGLRGDSVVL, 44–54 [A] | ribosome | |

| YDNGSVFSPEVLDLT | KGLRGDSVVL, 45–54 [A] | 4.61 | |||

| KINKGTVEI, 148–156 [A] | |||||

| gi|186513287 | argininosuccinate synthase | ALNGKALSPATLLAE | RGKLKKVVL, 93–101 [A] | plastid76 | |

| KKHNVPVPV, 255–263 [A] | 3.63 | ||||

| KKDMYMMSV, 293–301 [A] | |||||

| KLYKGSVSV, 393–401 [A] | |||||

| gi|15240765 | voltage dependent anion channel 2 | DITATLGSPVISFGA | KHPRFGLSLAL, 264–274 [A] | 2.41 | mitochondria, plasma membrane24 |

| gi|15218090 | putative mitochondrial-processing peptidase subunit alpha-1 | VAETSSSTPAYLSWL | mitochondria | ||

| LKIASETTPNPAASI | RKMKVEI, 196–202 [A] | 2.31 | |||

| GYSGPLASPLYAPES | |||||

| gi|334185190 | heat shock protein 70-3 | DLLLLDVTPLSLGLE | RARFEELNI, 305–313 [A] | 0.57 | nucleus, cytoplasm30 |

| RIPKVQQLLV, 348–357 [A] | |||||

| gi|14532542 | proteasome subunit alpha type-5-A | AVEKRITSPLLEPSS | KTKEGVVLAV, 41–50 [A] | 0.32 | peroxisome, cytoplasm (prediction) |

| gi|30691626 | heat shock protein 70-1 | GTSGTEQTPEAEFEE | KRSDNIDL, 289–296 [A] | 0.32 | cytosol77 |

| KKQLIDL, 573–579 [A] | |||||

| gi|30696056 | elongation factor EF-2 | EEMQRPGTPLYNIKA | KRLAKSDPMVV, 509–519 [A] | 0.08 | cytoplasm78 |

| KGLKEAMTPLSEFED | RLAKSDPMVV, 510–519 [A] |

Table 2. List of differentially regulated proteins containing both MAPK-specific phosphorylation site and MAPK docking site as predicted by GPS 3.0 software and Eukaryotic Linear Motif Resource (http://elm.eu.org/index.html) in the roots of the mpk6 mutant.

| Accesion number | Protein name | Phosphopeptide sequences | Docking sequence | Fold change | Cell compartment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gi|15230005 | regulatory particle triple-A ATPase 5A | *****MATPMVEDTS | RKGKCVVL, 102–109 [A] | unique in mpk6 | proteasome |

| KERFEKLGV, 194–202 [A] | |||||

| gi|15232671 | phospholipase D alpha 1 | AAAGFPESPEAAAEA | RRPKPGGDVTI, 244–254 [A] | unique in mpk6 | plasma membrane79, cytoplasm, nucleus (prediction) |

| RPKPGGDVTI, 245–254 [A] | |||||

| KKKASEGVRV, 259–268 [A] | |||||

| KKASEGVRV, 260–268 [A] | |||||

| KLRDLSDIII, 439–448 [A] | |||||

| RRAKDFIYV, 511–519 [A] | |||||

| RAKDFIYV, 512–519 [A] | |||||

| KGEKFRVYVVV, 561–571 [A] | |||||

| KFRVYVVV, 564–571 [A] | |||||

| gi|15232776 | cell division control protein 48-A | *****MSTPAESSDS | RKKSPNRLVV, 23–32 [A] | unique in mpk6 | nucleus, cytoplasm80 |

| KKSPNRLVV, 24–32 [A] | |||||

| KVVRSNLRVRL, 90–100 [A] | |||||

| RVRLGDVISV, 97–106 [A] | |||||

| RPVRKGDLFL, 148–157 [A] | |||||

| RKGDLFL, 151–157 [A] | |||||

| KSRAHVIV, 339–346 [A] | |||||

| RRFGRFDREIDI, 361–372 [A] | |||||

| RFGRFDREIDI, 362–372 [A] | |||||

| RFDREIDIGV, 365–374 [A] | |||||

| KNMKLAEDVDL, 389–399 [A] | |||||

| REKMDVIDL, 427–435 [A] | |||||

| RPGRLDQLIYI, 639–649 [A] | |||||

| gi|15233111 | cysteine synthase C1 | AYDLLDSTPDAFMCQ | KRDASLLI, 50–57 [A] | unique in mpk6 | plastids, cytosol, mitochondria81 |

| KSKNPNVKI, 238–246 [A] | |||||

| KGKLIVTI, 331–338 [A] | |||||

| gi|334186086 | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | APSLSCPSPSSSSKT | KKEKVSL, 88–94 [A] | 3.44 | plastid (prediction) |

| GWSVALGSPFTFATT | |||||

| gi|334185190 | heat shock protein 70-3 | DLLLLDVTPLSLGLE | RARFEELNI, 305–313 [A] | 3.15 | nucleus, cytoplasm30 |

| RIPKVQQLLV, 348–357 [A] | |||||

| gi|145324054 | arabinogalactan protein 31 | EVNHKTQTPSLAPAP | KFNRSLVAV, 180–188 [A] | 0.64 | cel wall72 |

| HPHPPAKSPVKPPVK | KKLGKSTVVV, 285–294 [A] | ||||

| PPVKAPVSPPAKPPV | KLGKSTVVV, 286–294 [A] | ||||

| PPVKPPVSPPAKPPV | |||||

| APVKPPVSPPTKPPV | |||||

| PPTKPPVTPPVYPPK | |||||

| gi|15221156 | pyrophosphate–fructose-6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase subunit beta 1 | RDLTAVGSPENAPAK | KKAMVEL, 512–518 [A] | 0.08 | plastid, cytoplasm (prediction) |

Abundance of abiotic stress related proteins in mpk4 and mpk6 mutants

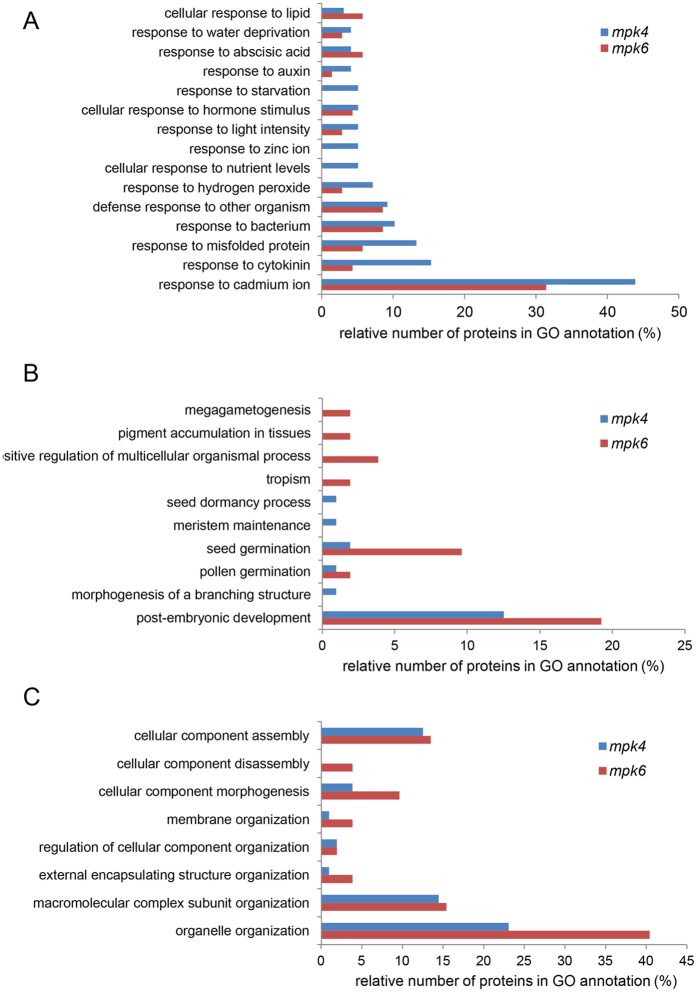

Considerable differences were found between the mutants in proteins annotated by GO “response to stress” (Fig. 2A). Therefore we focused in detail on GO annotations related to response to external stimuli in the differential proteomes of the mutants (Fig. 4A). Some GO annotation categories such as response to starvation, zinc ion and nutrient levels were not detected in the mpk6 mutant but they were present in the mpk4 mutant. Further, significantly more differentially-regulated proteins in the mpk4 mutant, as compared to the mpk6 mutant, were annotated for response to cadmium, cytokinin, misfolded protein, auxin and hydrogen peroxide. These analyses suggested that related physiological responses might be more altered in the mpk4 mutant in comparison to the mpk6 mutant.

Figure 4.

Comparison of gene ontology categories related to (A) response to external stimuli (6th level of ontology), (B) single-multicellular organism process (5th level of ontology) and (C) cellular component organization (4th level of ontology) between mpk4 and mpk6 mutants.

Both MPK4 and MPK6 are important signalling proteins during oxidative stress, albeit being activated by different signalling modules8,9. Roots of the mpk4 mutant showed decreased abundance of 7 proteins (monodehydroascorbate reductase, L-ascorbate peroxidase 1, L-ascorbate peroxidase S, peroxidase family protein, glutathione S-transferase phi 8, nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1 and peroxidase 27) involved in oxidative stress response and antioxidant defense as compared to the Col-0, while other 4 proteins (glutathione S-transferase F2, glutathione S-transferase TAU 19, monodehydroascorbate reductase (NADH) and catalase 3) were upregulated. Consistently, bioinformatic analysis of interaction networks of proteins with increased abundance in the mpk4 mutant showed the downregulation of cluster composed of enzymes involved in ascorbate-glutathione cycle (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, in the mpk6 mutant, we detected only one antioxidant enzyme, monodehydroascorbate reductase (NADH), which is downregulated in comparison to the wild type control. These data indicate that the Arabidopsis antioxidant defense might be regulated predominantly by MPK4.

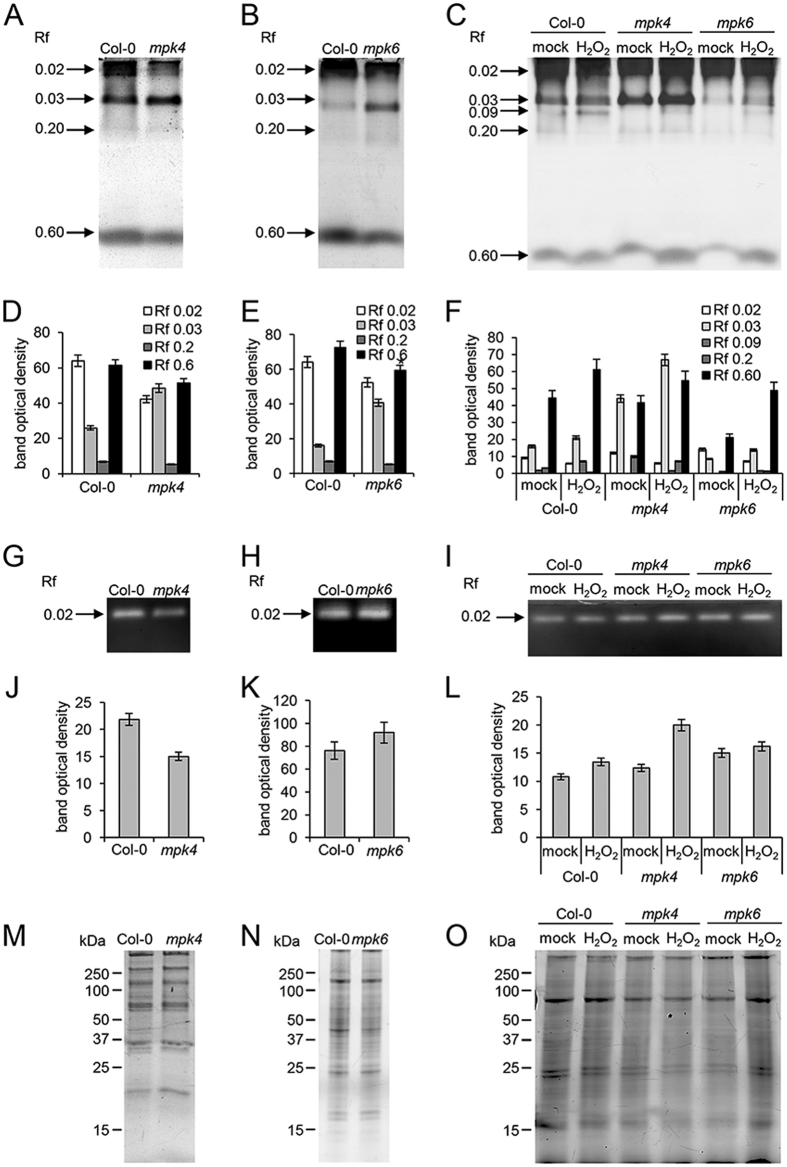

In order to monitor the activities of hydrogen peroxide decomposing enzymes in mpk4 and mpk6 roots, we carried out specific activity staining of peroxidases and catalase on native PAGE gels. We detected four isozymes of peroxidases in both mutants and wild type. Three isozymes (with Rf 0.02, 0.03 and 0.6) showed substantial differences between Col-0 and the mutants (Fig. 5A,B,D,E). The changes in peroxidase isozymes were similar in both mutants when compared to the wild type. To analyze activities of peroxidase isozymes under oxidative stress, we exposed the wild type, mpk4 and mpk6 seedlings to 150 μM hydrogen peroxide (in liquid 1/2 MS for 24 h). The total peroxidase activity was apparently higher in the mpk4 mutant as compared to the wild type after incubation in mock treatment (liquid 1/2 MS medium), while it was reduced in the mpk6 mutant (Fig. 5C,F). Hydrogen peroxide activated one peroxidase isozyme with Rf 0.09 in Col-0 control while the other isozymes remained unaffected. On the other hand, the overall peroxidase activity was increased in response to hydrogen peroxide in both mutants (especially isozymes with Rf 0.02 and 0.03 in Fig. 5C,F).

Figure 5. Analyses of peroxidase and catalase enzymatic activities in the mpk4, mpk6 mutant and in the wild type.

(A–C) Peroxidase specific activity staining in mpk4 and mpk6 mutant roots without any treatment (A,B) or after 1 day long incubation in liquid 1/2 MS medium with or without 150 μM hydrogen peroxide (C). (D–F) Quantification of the bands optical densities in A, B and C. (G–I) Catalase specific activity staining in mpk4 and mpk6 mutant roots without any treatment (G,H) or after 1 day long incubation in liquid 1/2 MS medium without or with 150 μM hydrogen peroxide (I). (J–L) Quantification of the bands optical densities in G, H and I. (M–O) Respective loading control represented by protein visualization using stain free technology (Biorad) on SDS PAGE gels. Error bars are standard deviations calculated from 3 biological replicates.

Further, we observed significantly lower total catalase activity in the mpk4 mutant while it was slightly elevated in the mpk6 mutant when compared to wild type (Fig. 5G,H,J,K). On the other hand, catalase activity significantly increased in response to the hydrogen peroxide treatment only in the mpk4 mutant. These results show that mpk4 and mpk6 mutant roots have similar basal and hydrogen peroxide-induced peroxidase isozyme pattern compared to Col-0. In contrast to peroxidase, total catalase activity in control conditions and also in response to hydrogen peroxide showed noticeable differences between the mutants.

mpk4 and mpk6 mutants show differences in defense related proteins

MPK4 and MPK6 are activated by different MAPK cascades in response to the pathogen attack20. Therefore, it is challenging to decipher whether this difference affects the composition of the defense related proteins in the mpk4 and mpk6 mutants.

We detected a canonical defense inducible protein, root specific beta-1,3-endoglucanase21 and DNA topoisomerase (named as NAI2)22 as upregulated in the mpk4 mutant roots, supporting well-known activation of pathogen defense in the mpk4 mutant23. These proteins, together with JA responsive 1, form an interaction cluster showing increased abundance in the mpk4 mutant as revealed by STRING functional protein association network analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Similarly, some other pathogen inducible proteins were upregulated as well. These included mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel24, short-chain dehydrogenase reductase 325 and finally Kunitz trypsin inhibitor, which acts as antagonist of cell death triggered by phytopathogens26. Strikingly, not all pathogenesis related proteins showed constitutively increased abundances in the mpk4 mutant. Thus, glutathione S-transferase 8 known as marker for early defense response27 and heat stable protein 1 with antimicrobial activity28 were downregulated (Supplementary Table S1). Another two downregulated proteins in the mpk4 mutant are involved in virus multiplication. The TOMV RNA binding protein binds to tomato mosaic virus genomic RNA and inhibits its multiplication29. HSP70–3 interacts with Turnip mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and is a component of a replicase complex regulating RdRp function30. HSP70–3 was also shown to regulate plant immune responses against bacteria in interaction with co-chaperone SGT131. Therefore, MPK4 might modulate virus multiplication.

In addition to these proteins, jasmonic acid (JA) responsive protein 1 (JR1) was less abundant in the mpk4 roots (Supplementary Table S1). Since JR1 is accumulating during JA response32 it indicates downregulation of JA signalling pathway in the mpk4 mutant. On the other hand, JA-inducible lipoxygenase1 (LOX1), which is also involved in JA biosynthesis33 was detected uniquely in the mpk6 mutant (Supplementary Table S2), suggesting upregulation of JA signalling in this mutant. Altogether, these data indicate different regulation of JA signalling by MPK6 and MPK4.

The mpk6 mutant showed also increased abundances of NADP-dependent malic enzyme 2, an enzyme important for pathogen defense34 and CDC48 protein responding to pathogen infection and controlling movement of Tobacco mosaic virus35. Finally, the HSP70–3, unlike in the mpk4, was upregulated in the mpk6 mutant (Supplementary Table S2).

Differential abundance of scaffold proteins RACK1 and AtRem1.3 in mpk6 and mpk4 mutants

WD-40 repeat ArcA-like protein (RACK1) was detected uniquely in the mpk6 mutant (Supplementary Table S2), while it was under the detection threshold in the mpk4 mutant. RACK1 functions as a scaffold protein linking MEKK1-MKK4/MKK5-MPK3/MKP6 cascade during immune pathway activated by pathogen-secreted proteases36. In addition, RACK1 has a multiple roles in plant development and hormone responses37. According to our results, MPK6 may negatively regulate the expression of RACK1 in Arabidopsis.

Another scaffold protein involved in plant-microbe interactions is remorin family protein (AtRem1.3) which showed decreased abundance in the mpk4 mutant (Supplementary Table S1). AtREM1.3 is differentially phosphorylated upon treatment with bacterial elicitors and likely plays a role as scaffold protein in plant innate immunity38. Our data provide a first evidence of possible co-regulation of AtRem1.3 and MAPK signalling.

Plant developmental proteins in mpk4 and mpk6 mutants

Considerable differences between mpk4 and mpk6 mutants have been found in GO category named single-multicellular organism process (Fig. 2A). Further, we focused on downstream GO annotations within the GO hierarchy (Fig. 4B). This GO annotation contains proteins implicated mainly in developmental processes. According to this evaluation, root proteome of mpk6 contained proteins involved in megagametogenesis, pigment accumulation in tissues and tropism, while such GO annotations were not present in the root proteome of mpk4 mutant. In addition, mpk6 proteome contained a higher number of proteins involved in seed germination as compared to mpk4. On the other hand, mpk4 root proteome contained more proteins involved in seed dormancy and meristem maintenance.

Further, we manually selected differentially-regulated developmental proteins in both mutants. These proteins and their specific roles in plant development are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Differentially abundant proteins in the mpk4 involved in the plant development as classified according to GO annotations.

| Accession | Protein name | Fold change | Developmental process |

|---|---|---|---|

| gi|18417863 | 14-3-3-like protein gf14 upsilon | unique in WT | root formation, chloroplast development82 |

| gi|30682607 | mRNA decapping complex vcs | unique in WT | leaf blade development83; early seedling development46 |

| gi|30695409 | acetoacetyl- thiolase 2 | unique in WT | pollen tube elongation, embryogenesis84 |

| gi|15219345 | metacaspase 4 | unique in WT | embryogenesis85 |

| gi|15224838 | profilin 1 | 0.36 | root hair formation63 |

| gi|15233538 | profilin 2 | 0.25 | root hair formation63 |

| gi|18379240 | mlp-like protein 328 | 0.35 | bolting86 |

| gi|15231255 | tcp-1 cpn60 chaperonin family protein | 0.23 | plastid division87 |

| gi|145329204 | triosephosphate isomerase | 0.45 | transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth88 |

| gi|15234781 | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase cyp1 | 0.54 | stem elongation and shoot branching89 |

| gi|15237054 | v-type proton atpase subunit e1 | 0.11 | embryo development90 |

| gi|145323784 | l-ascorbate peroxidase 1 | 0.24 | embryogenesis91 |

| gi|30686836 | dehydrin erd10 | 0.32 | seed development92 |

| gi|145333043 | adenosylhomocysteinase 1 | 25.25 | seed and root development93 |

| gi|18410982 | s-phase kinase-associated protein 1 | mpk4 unique | cell division, meiosis94,95, meristem activity96, seedling development97 |

| gi|15233740 | hsp90-like protein GRP94 | 4.99 | shoot, floral and root meristem function45 |

Only proteins with published experimental evidence for their role in the plant development are listed here.

Table 4. Differentially abundant proteins in the mpk6 involved in the plant development as classified according to GO annotations.

| Accession | Protein name | Fold change | Developmental process |

|---|---|---|---|

| gi|145333041 | glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 2 | 0.136 | seedling development and germination98, flower and seed development99 |

| gi|15220770 | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 2 | 0.094 | ethylene synthesis71, seed germination100,101 |

| gi|15231569 | aquaporin tip1-2 | 0.077 | lateral root emergence102 |

| gi|15228041 | aquaporin tip1-1 | 0.053 | lateral root emergence102 |

| gi15233538 | profilin 2 | 0.209 | root hair formation63 |

| gi|30691988 | chaperone protein dnaj 3 | 0.136 | flowering103 |

| gi|18403295 | gamma-aminobutyrate transaminase pop2 | 0.139 | cell wall composition, root and hypocotyl development104 |

| gi|15229522 | adenosylhomocysteinase 2 | 1.594 | seed and root development93 |

| gi|15222075 | actin 8 | unique in mpk6 | root hair tip growth105 |

| gi|30683070 | tubulins | 5.012 | helical root growth106, gravitropism107 |

| gi|15242516 | actin 7 | 5.805 | callus formation108; seed germination and root growth109, cell division105 |

| gi|15232671 | phospholipase d alpha 1 | unique in mpk6 | stomatal closure110 |

| gi|15220941 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-like protein a | unique in mpk6 | root formation, seed germination and seedling development37,111 |

| gi|15221970 | lipoxygenase 1 | unique in mpk6 | formation of lateral roots112 |

| gi|15230005 | regulatory particle triple-a atpase 5a | unique in mpk6 | gametophyte development113, root apical meristem maintenance114 |

| gi|15232776 | cell division control protein 48-a | unique in mpk6 | cell division, expansion and differentiation48 |

| gi|15233320 | aquaporin tip2-1 | unique in mpk6 | lateral root emergence102 |

| gi|30691619 | elongation factor 1b beta | unique in mpk6 | cell wall formation and cell expansion115 |

Only proteins with published experimental evidence for their role in the plant development are listed here.

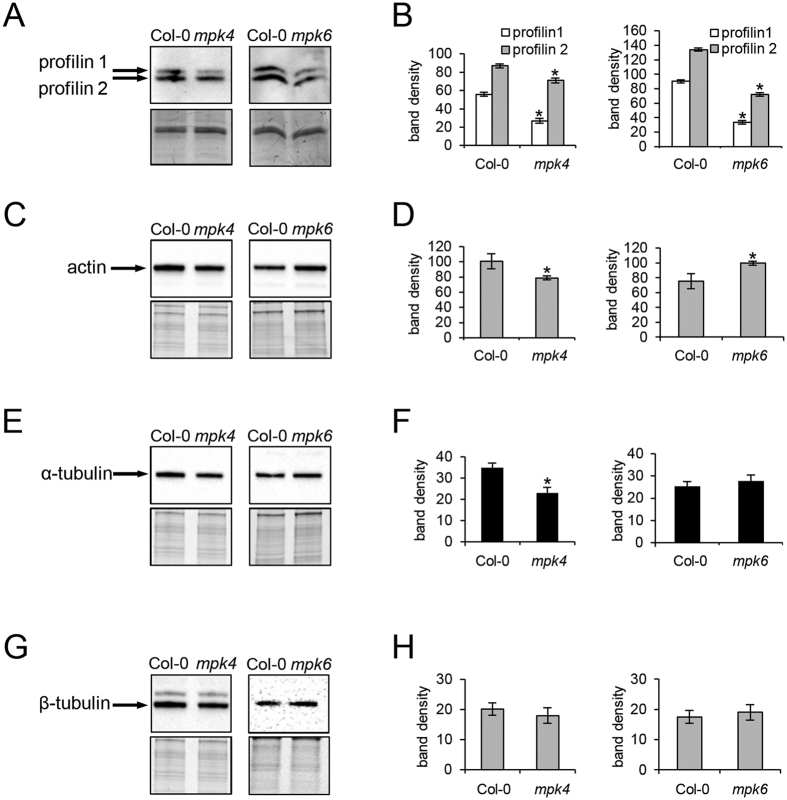

The cytoskeletal proteins are crucial regulators of cell division, elongation and growth. Both mutants are known for their altered organization of cortical and mitotic microtubules12,13,14. However, nothing is known about actin cytoskeleton in these mutants. Our results revealed changed abundances of several actin isoforms and actin binding proteins important for actin organization and dynamics in both mpk4 and mpk6 mutants. Thus, the mpk4 mutant showed lower levels of profilin isoforms 1 and 2 (PRF1 and PRF2) when compared to the Col-0 wild type (Table 3). This was proven also by immunoblotting analysis using antibody recognizing both PRF1 and PRF2 (Fig. 6A,B). Profilin regulates actin polymerization while Arabidopsis prf1 mutant plants display increased number of root hairs, a phenotype similar to the mpk439. Dehydrin ERD10 has actin stabilizing activity40 and it was downregulated in the roots of the mpk4 mutant. Moreover, annexin 1 showed more than four-fold higher abundance in this mutant. Annexins are stress induced proteins involved in actin filament bundling and in vesicular trafficking in plants41. Therefore, changed abundances of above-mentioned actin binding proteins suggest modifications of actin cytoskeleton organization in the mpk4 mutant.

Figure 6.

Immunoblotting differential analyses of profilins (A,B), actin (C,D), alfa-tubulin (E,F) and beta-tubulin (G,H) in the mpk4 and mpk6 mutants. Graphs depict optical density quantifications of relevant proteins. Loading controls are provided beneath the relevant immunoblots. Error bars are standard deviations calculated from 3 biological replicates. Stars indicate significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 according to Student t-test.

Actin cytoskeleton appeared to be altered also in the mkp6 mutant, as indicated by the downregulation of actin 7 and profilin 2. On the other hand, actin 8 and actin-like ATPase superfamily protein were uniquely detected in the mpk6 mutant and this might contribute to the regulation of actin cytoskeleton organization in the mutant. Moreover, increased actin abundance in the mpk6 and decreased abundances of PRF1 and PRF2 were corroborated by immunoblotting using actin antibody recognizing all actin isoforms and profilin antibody recognizing PRF1 and PRF2 (Fig. 6A,B,C,D). Further, we detected increased abundance of alpha tubulin 5 and 6 in the mpk6 mutant. Consistently, immunoblotting analysis showed slight overabundance of tubulin isoforms in the mpk6 mutant, while lower abundances were encountered in the mpk4 mutant (Fig. 6E–H). This analysis showed that abundances of tubulin isoforms were differently regulated in both mutants.

Phospholipase D alpha 1 (PLDa1), an enzyme producing phosphatidic acid (PA) and its lipid derivatives, was uniquely detected only in the mpk6 mutant. PLDa1-derived PA binds to MAP65–1, enhances its activity during microtubule polymerization and bundling42. PA is capable also to activate MPK643. Our proteomic data point to possible negative regulation of PLDa1 abundance by MPK6 and this might contribute to the altered cortical microtubule organization in the mpk6 mutant12. PLDa1 is a putative candidate for MPK6-dependent phosphorylation as suggested by bioinformatic analysis (Table 2).

Additionally, several other proteins directly involved in cell division, a process controlled by both MPK6 and MPK4 12,14, were detected in both mutants (Tables 3 and 4). S-phase kinase-associated protein 1, subunit of an E3 ubiquitin ligase known as the SCF complex, was detected only in the mpk4 mutant (Table 3), suggesting its increased abundance. This protein might act downstream of MPK4 in the regulation of cell division and meristem activity. Next, CDC-48A which localizes at the cell division plane during cytokinesis and contributes to membrane fusion events44 was overabundant in the mpk6 mutant (Table 4). Thus it might be involved in ectopic and disoriented cell divisions of this mutant12.

Other proteins important for root growth and embryogenesis were predominantly downregulated in the mpk4 mutant, consistently with its firmly reduced growth. For example, HSP90-like protein GRP94 (known also as SHEPERD) was five-fold upregulated (Table 3). This protein is important for CLAVATA receptor kinase folding and shd mutants show root apical meristem phenotype with disorganized columella cells and altered organization of initials and central cells45.

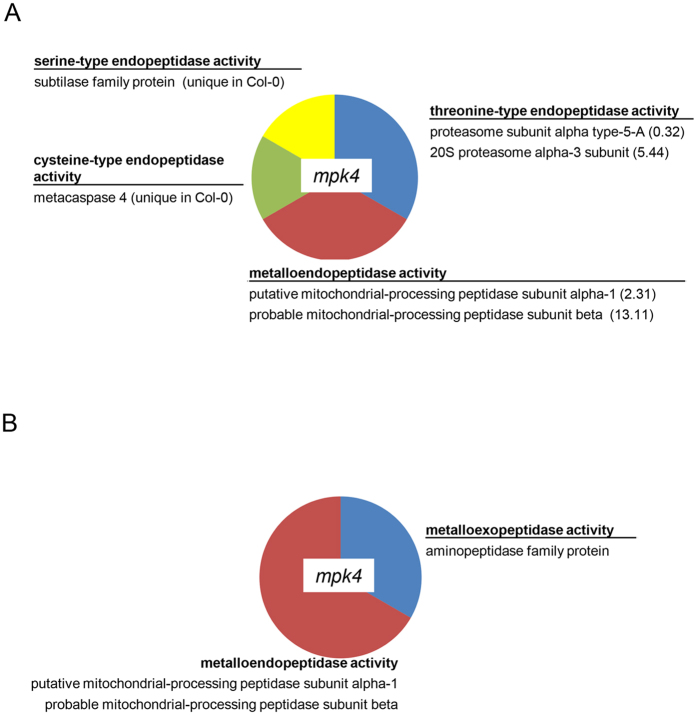

Proteomics revealed differences in cellular compartment morphogenesis, endopeptidase activity and RNA processing between mpk4 and mpk6 mutants

Another GO annotation showing significant differences between mpk4 and mpk6 mutants in terms of biological process was cellular component organization (Fig. 2A). The mpk6 mutant contained a higher number of proteins annotated to this class. Further evaluation showed that the mpk6 differential proteome contained a higher number of proteins annotated to morphogenesis of cellular components, membrane organization, external encapsulating structure organization and organelle organization (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the mpk6 differential proteome uniquely contained proteins involved in cellular component disassembly such as lipoxygenase 1 and glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 2.

In terms of molecular function, root proteome of the mpk4 mutant contained three GO annotations which were absent in the mpk6 mutant (Fig. 2B). The mpk4 mutant contained differentially regulated proteins with endopeptidase and metallopeptidase activity (Fig. 7A,B). Proteins with endopeptidase activity included proteases with different specificity depending on amino acids (Fig. 7A). This might indicate differences in proteolytic processes in the mutants.

Figure 7.

Graphs showing gene ontology categories related to (A) endopeptidase activity and (B) metalopeptidase activity in the mpk4 mutant.

Finally, proteomic analysis indicated decreased abundance of mRNA decapping complex VCS (known also as varicose) in the mpk4 mutant. This protein is the component of the decapping complex, that removes the 7-methyl-guanosine 5′-diphosphate from the 5′ end of mRNAs. Decapping allows rapid changes in gene expression and is important for many stress related and developmental processes46. This protein contains the MAPK docking site and specific phosphorylation site in its amino acid sequence (Table 1) suggesting that it might be a putative substrate target of MPK6. Indeed, the MPK4-induced changes in VCS levels may contribute to deregulation of gene expression and resulting changed protein abundances in the mpk4 mutant. Nevertheless, this hypothesis should be experimentally tested in future studies.

Discussion

Considering versatility of MPK4 and MPK6 functions, OMICS technologies such as transcriptomics, proteomics and phosphoproteomics are powerful techniques to investigate different aspects of MAPK signalling15. They provide a wide range of information about transcripts and proteins being modified in MAPK mutants and help to identify new MAPK targets.

In this study, we aimed to decipher root proteomes of two Arabidopsis mpk4 and mpk6 mutants. Both MPK4 and MPK6 are known to be activated by oxidative stress and pathogens, however, they are likely involved in different MAPK signalling pathways4,5,8,9. Differential proteomic analysis of plants with genetically manipulated MAPKs could be useful for investigation of proteome-wide changes in such plants15.

Identification of putative MPK4 and MPK6 targets

It was previously reported that MAPK knock-out mutants show changes in the transcriptional levels of some respective MAPK phosphorylation targets47. Using bioinformatic analysis we were able to predict several putative targets of MPK4 and MPK6 in analyzed proteomes. These were proteins of diverse localizations and functions and in some cases it corresponded well with known localization and function of MPK4 and MPK6. For example, CDC48A, which was detected only in the mpk6 mutant is localized to the cell plate during cytokinesis, similarly to MPK648,49. This indicated that CDC48A might be a putative target protein which is regulated by MPK6.

One protein candidate involved in gene transcription in the mpk4 mutant is the mRNA decapping complex VCS which was detected only in the wild type plants (indicating its downregulation in the mpk4 mutant). This protein might be, at least partially, responsible for MPK4-dependent transcriptomic and proteomic changes in Arabidopsis roots. mRNA decapping complex VCS was also found by phosphoproteomic study of transgenic plants expressing GVG:FLAG-NtMEK2DD (constitutively active after dexamethasone treatment) as a putative MAPK target50. In this respect, two other proteins from our list, namely elongation factor EF2-like protein LOS1 and HSP 70–3 were also proposed as MAPK phosphorylation targets by protein microarray51.

Distinct proteome composition of mpk4 and mpk6 mutants

Our proteomic analysis showed that knockout MPK4 mutation affected broader range of proteins in Arabidopsis roots compared to MPK6 knockout. A similar pattern was observed also in the recent transcriptomic study, which reported 1235 genes differentially expressed in the mpk4 mutant but only 61 genes in the mpk6 as compared to the Col-047, although the difference in two mutant proteomes was not so pronounced as in the transcriptomic study. Nevertheless, it suggests that MPK4 has likely broader impact on the regulation of biological protein-dependent processes in Arabidopsis root when compared to MPK6. Next, GO annotation analysis showed functional categories unique either for mpk4 or mpk6 mutant differential proteomes. Proteins with peptidase activity as well as those involved in response to zinc, starvation and changing nutrient levels were affected in the mpk4, but not in the mpk6 mutant. On the other hand, proteins involved in several developmental processes and cellular component disassembles were altered only in the mpk6 mutant.

The relatively low number of differentially regulated proteins in mpk6 mutant root implies that the absence of MPK6 might be compensated by MPK3, which is partially redundant to MPK6. Previously it was reported that MPK3 activities could be increased in the mpk6 mutant in response flagellin in whole seedlings47 or hypoxia52 and ethylene in leaves53. However, little is known about basal abundance and activity of MPK3 in the mpk6 mutant and even less emphasis was given on MPK3 levels and activity in resting mutant roots so far. Published data refer about small overlap in transcriptomic profiles of 2 weeks old mpk3 and mpk6 mutant seedlings under control conditions47 as well as leaf proteomes of 6 weeks old mpk3 and mpk6 mutants expressing MKK5DD inducible by dexamethasone54.

Considering MPK3 abundance, no differences were found in the leaves of 5 weeks old mpk6 mutant and wild type plants55. These data indicate that MPK3 might not compensate for MPK6 deficiency in the leaves of the mpk6 mutant. In the 2 weeks old roots of the mpk6 mutant, we have found higher abundance but lower activity of MPK3. Thus, the capability of MPK3 to compensate for MPK6 deficiency might depend on tissue and developmental stage of plants.

The constitutive induction of pathogen defense is related to upregulation of ER body proteins in the mpk4 mutant

Present proteomic analysis confirmed some known information about defense responses in Arabidopsis roots mediated by MPK4 and MPK6. For example, while MPK6 is a negative regulator of JA signalling7, MPK4 positively affects the JA signalling pathway23. This is fully consistent with elevated abundance of lipoxygenase 1, an enzyme crucial for JA synthesis, in the mpk6 roots as well as with decreased abundance of jasmonic acid responsive protein 1 in mpk4 roots found in our study.

MPK6 phosphorylates 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase 2 and 6 leading to promotion of ethylene production6. We have found decreased abundance of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 2 in the mpk6 mutant, suggesting additional level of ethylene regulation by MPK6.

On the other hand, abundances of pathogen related proteins were not fully consistent with constitutive activations of pathogen related proteins in the mpk4 mutant4,23. We detected several ER-resident pathogenesis related proteins as upregulated in the mutant. These proteins are involved in ER body formation56,57, which is an important component of plant pathogen defense22. NAI2, beta glucosidase and JAL34 were identified in the mpk4 mutant as upregulated, and they are controlled by transcription factor named NAI1. The analysis of MAPK-specific phosphorylation sites of NAI1 showed that MAPKs are most probable kinases responsible for phosphorylation of this transcription factor (Supplementary Table S9). NAI1 also contains docking motif for interaction with MAPK (Supplementary Table S10). All this implies that the constitutive activation of defense response in the mpk4 mutant might be connected to ER body formation. Moreover, MAPKs such as MPK4 might be crucial regulators of ER body formation controlled by the phosphorylation of NAI1.

Still, several proteins involved in pathogen defense were downregulated in the mpk4 mutant. This could be perhaps explained by the selective activation of the pathogen defense by MPK4, depending on leucine-rich receptors58.

MPK4 is important for antioxidant defense

Members of MAPK cascades are important mediators of antioxidant defense in plants. This was shown for MKK5 in high-light induced oxidative stress for Cu/Zn SOD59 and salinity induced FeSOD60 as well as for MKK1 and MPK6 in the regulation of CAT161. Here we report, that roots of mpk4 mutant possess increased levels of some proteins and enzymes involved in antioxidant defense. Similarly, increased levels of transcripts of antioxidant genes were obtained in transcriptomic study on seedlings9. Such increased antioxidant defense correlates with increased levels of ROS in the mpk4 mutant4. When compared to mpk4, mpk6 roots showed decreased abundance of monodehydroascorbate reductase.

Since these proteomic data revealed that the antioxidant defense might be differentially regulated by these two kinases, we aimed to examine enzymatic activities of peroxidase and catalase decomposing hydrogen peroxide. Our results showed that mainly catalase activity was significantly upregulated in the mpk4 mutant, unlikely to the mpk6 mutant. Previously we reported that constitutive upregulation of antioxidant defense caused increased tolerance of Arabidopsis anp2anp3 double mutant to the oxidative stress62. Similarly, our present data point to possible negative regulation of antioxidant defense by MPK4.

Proteomic analysis deciphering mpk4 and mpk6 root phenotypes

Both mutants have distinct phenotypes. The mpk4 mutant shows severely reduced growth23 and short roots with radial expansion and strong root hair defects13. At the subcellular level, the mpk4 mutant has cytokinetic defects resulting from various abnormalities in mitotic spindle and phragmoplast rearrangements14. Knockout mpk6 mutant displays “no root”, “short root” or “long root” phenotypes at early seedling development and increased number of adventitious roots at the later developmental stages, as well as ectopic cell divisions and defective cell plate orientation12,66.

In fact, some proteins directly involved in cell division were altered in both mutants. CDC-48A protein, a potential MPK6 phosphorylation target (see discussion above), which contributes to cell division plate formation44, showed overabundance in the mpk6 mutant. Since MPK6 localizes in spots close to cell plate and determines the cell plane orientation12 these data might indicate a negative regulation of CDC-48A by MPK6 during cell plate formation.

Concerning actin cytoskeleton, both mutants showed decreased abundance of profilins PRF1 and PRF2. Profilin is an actin binding protein crucial for root hair formation63, a process which is severely altered in the mpk4 mutant13. Plant profilins regulate actin polymerization dynamics and filament initiation together with other actin-binding proteins (ABPs) such as actin depolymerizing factors (ADFs), actin-related proteins (ARPs) and formins. Depending on the equilibrium between these ABPs actin polymerization might be either promoted or inhibited64. Since actin polymerization and dynamics is important for cell and organ elongation growth–hypothetically, less profilins and less actin might be connected with shorter roots in the mpk4 mutant while less profilin but more actin and ADF might result in dominating long-root phenotype in the mpk6 mutant.

In conclusion, present proteomic study identified several protein candidates contributing to the phenotypes and defense responses in the Arabidopsis mpk4 and mpk6 mutants, and paved the way for their functional characterization in the future studies.

Materials and Methods

Material

Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana, wild type (ecotype Col-0), mpk413 and mpk6–212 mutants were grown vertically on Petri dishes with 1/2 Murashige-Skoog solid culture medium65 (pH 5.7) (16 h light/8 h dark, 22 °C). For mpk6–2 mutant, seedlings displaying “short root” and dominating “long root” phenotypes66 were used for the analyses. Roots were collected for proteomic and biochemical analyses two weeks after germination. Proteomic analyses were performed on four independent biological replicates.

Protein extraction for proteomic analysis

Proteins were extracted as described previously67. Roots of Arabidopsis wild type plants and mutants were homogenized in liquid nitrogen to fine powder and extracted in buffer containing 0.9 M sucrose, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl and 0.4% v/v 2-mercaptoethanol. Total proteins were obtained from the extract using phenol extraction followed by precipitation in methanolic ammonium acetate (100 mM), and sequential purification in 80% v/v acetone, 70% v/v ethanol, and final incubation with 80% v/v acetone. The final protein pellet was dissolved in 6 M urea in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8. Proteins were reduced and alkylated prior to trypsin digestion (1 μg of trypsin was applied to 50 μg of proteins). Digested peptides were desalted on C18 cartridges (Sep PAK, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and vacuum dried.

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Spectral data were collected using an Orbitrap LTQ Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using Xcalibur version 2.1.0 united with an UltiMate 3000 nano flow HPLC system (Dionex). Two μg of protein tryptic digest were loaded on reversed phase fused silica C18 column measuring 75 μm × 150 mm (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were separated and eluted at a constant flow rate of 0.3 μl.min-1 by a 170-minute long nonlinear gradient of acetonitrile (in 0.1% formic acid) as follows: 2–55% for 125 min, 95% for 15 min, 5% for 30 min. Peptides were detected in linear trap mass spectrometer operated in a data dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. The mass spectra were obtained in the data dependent mode, with dynamic exclusion being applied, in 18 scan events: one MS scan (m/z range: 300–1700) followed by 17 MSMS scans for the 17 most intense ions detected in the MS scan. Other critical parameters were set as follows: Normalized collision energy: 35%, AGC (automatic gain control) “on” with MSn Target 4 × 104, isolation width (m/z): 1.5, capillary temperature 170 °C, spray voltage 1.97 kV.

The .raw files were searched using the SEQUEST algorithm of the Proteome Discoverer 1.1.0 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with following selection of parameters: Lowest and highest charge: +1 and +3, respectively; minimum and maximum precursor mass: 300 and 6000 Da, respectively; minimum S/N ratio: 3; enzyme: trypsin; maximum missed cleavages: 2, FDR = 0.01; dynamic modifications: cysteine carbamidomethylation (+57.021), methionine oxidation (+15.995), methionine dioxidation (+31.990).

The spectral data were matched against target and decoy databases (later being created automatically by the software). The NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) Arabidopsis genus taxonomy referenced protein database (67,924 entries as of November 2013) served as the target database, while its reversed copy served as a decoy database. The Proteome Discoverer results files (.msf) were uploaded to ProteoIQ 2.1 (NuSep) software for further filtering. Only proteins detected with at least three spectral counts, FDR < 1%, 95% probability and listed as “Top” proteins (defined by ProteoIQ, “Within a protein group, each and every respective peptide could be matched to the top protein”) are considered as high confidence matches and are presented in the results. The relative quantitative analysis was based on sums of precursor ion intensities of filtered peptides attributed to given proteins. The ANOVA analysis of four replicates for each biological sample was performed and p ≤ 0.05 was used to filter statistically significant results.

Bioinformatic evaluation of proteomic data

Proteins with statistically significantly changed abundances as well as those detected uniquely in one of the two analyzed samples were subjected to gene ontology annotation using Blast2Go17 software. The full sequences retrieved from NCBI database were blasted against Plants/Arabidopsis thaliana protein sequences allowing 1 BLAST Hit, followed by mapping step and annotation by using these parameters: E Value Hit filter: 1.0E-6; Annotation cut off: 55; GO weight: 5. One GO level was used for the evaluation of GO annotations according to molecular function, biological process and compartment.

Amino acid sequences of proteins with statistically significantly changed abundances as well as those detected uniquely in one of the two analyzed samples were screened for the presence of MAPK specific docking domains using Eukaryotic Linear Motif (ELM) resource68. The identified proteins were further screened for the presence of MAPK-specific phosphorylation motif by using GPS 3.0–Kinase-specific Phosphorylation Site Prediction69. Finally, Wolf Psort prediction tool (http://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html) was used for the prediction of protein subcellular localization.

Immunoblotting analysis of actin, tubulin and profilin abundances in MAPK mutants

Protein extracts obtained by phenol extraction were enriched with SDS sample buffer and 2-mercaptoethanol (5% v/v) and used for immunoblotting analysis. For SDS-PAGE, Stain FreeTM technology (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) was applied allowing UV-based visualization of proteins on gel and membrane to ensure equal sample loading. Identical protein amounts were loaded for each sample. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) in a wet tank unit (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 100 V for 1.5 h. For immuno-detection of protein bands, the membrane was blocked in a mixture of 4% w/v low-fat dry milk and 4%w/v bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered-saline (TBS, 100 mM Tris-HCl; 150 mM NaCl; pH 7.4) for 1 hour, and subsequently incubated with anti-profilin, anti-beta tubulin, anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), and anti-alpha tubulin (Abd Serotec, Kidlington, UK) at room temperature for 1.5 h. After it, they were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), diluted 1:5000 in TBS-T containing 1% w/v BSA at room temperature for 1.5 h. Following five washing steps in TBST, proteins were detected by incubating the membrane in Clarity Western ECL substrate (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). Luminescence was detected using Chemidoc MP documentation system (Biorad). Immunoblot analyses were performed in three biological replicates. The band signal density was quantified using Image Lab 4.0.1 software (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). The differences between the mutants and the wild type were statistically evaluated using Students t-test (n = 3).

Immunoblotting analysis of MPK3 and MPK6 activities

For the examination of MPK3 activity in Col-0 and mpk6 mutant roots, we extracted the proteins in E buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaF,10% v/v glycerol, Complete™ EDTA-free protease inhibitor and PhosSTOP™ phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (both from Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Following centrifugation, equal protein aliquots were subjected to overnight precipitation by addition of 5 volumes of 80% ice cold acetone. The resulting precipitates were dissolved in SDS sample buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 minutes. Immunoblotting was performed as described above, using polyclonal antibody against mammalian phosphorylated ERK1/2 (phospho-p44/42, pERK; Cell Signaling; Danvers, ME, USA). The differences between the mutants and the wild type were statistically evaluated using Students t-test (n = 3).

Analysis of enzymatic activities

For the assessment of enzymatic activities in untreated plants, we harvested the roots of the wild type Col-0 plants as well as mpk4 and mpk6 mutants grown 14 days on solid ½ MS. For the examination of enzymatic activities in response to oxidative stress treatment, 14 days old seedlings were incubated either in liquid ½ MS medium, or in the same medium supplemented with 150 μM H2O2 for 24 h. For preparation of native protein extract, roots were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and the homogenate was incubated with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 1 mM EDTA, 10% v/v glycerol and “Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Following centrifugation at 13000 g at 4 °C, protein content was estimated in supernatants using Bradford assay70. Equal protein amounts were used for further analyses. Isozymes of peroxidases and catalase were separated on 12% native PAGE at constant 10 mA/gel. For visualization of peroxidases, gels were first equilibrated in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5,2) buffer for 15 min, followed by incubation in 0.05% (w/v) o-dianizidine and 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2). Catalase isozyme was visualized according to Aebi71. Gels were three times washed in distilled water for 5 minutes followed by incubation in 0.006% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. Catalase activity appeared as negative bands after 5 min of gel incubation in 1% (w/v) potassium ferricyanide and 1% (w/v) ferric chloride in distilled water. The band intensities were calculated using Image Lab 4.0.1 software (Biorad). Analyses were performed in biological triplicates. Statistical evaluation of data was carried out using Student’s t-test. As a loading control equal amounts of protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE as described above with the exception that precast 4–12% gradient gels (Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast Gels, BioRad) were used allowing UV-induced total protein visualization with Chemidoc MP imaging system (BioRad). All experiments were carried out in biological triplicates.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Takáč, T. et al. Comparative proteomic study of Arabidopsis mutants mpk4 and mpk6. Sci. Rep. 6, 28306; doi: 10.1038/srep28306 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Program for Sustainability I (grant no. LO1204) provided by the Czech Ministry of Education, Institutional Fund of Palacký University Olomouc (TT, PV and OŠ) and by the student project IGA_PrF_2016_012 of the Palacký University Olomouc. This work was funded in part by grant NIH 2P20GM103476-12 (MS-INBRE).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.Š. conceived and designed the experiments, T.T., P.V., T.P., I.L. and O.Š. made the analyses, T.T., J.Š. and P.V. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Smékalová V., Doskočilová A., Komis G. & Šamaj J. Crosstalk between secondary messengers, hormones and MAPK modules during abiotic stress signalling in plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 2–11 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet J. & Hirt H. Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem. J. 413, 217–226 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teige M. et al. The MKK2 Pathway Mediates Cold and Salt Stress Signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 15, 141–152 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M. et al. MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res. 18, 1190–1198 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T. et al. MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415, 977–983 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. & Zhang S. Phosphorylation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase by MPK6, a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase, induces ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 3386–3399 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi F. et al. The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade MKK3–MPK6 Is an Important Part of the Jasmonate Signal Transduction Pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 805–818 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtun Y., Chiu W. L., Tena G. & Sheen J. Functional analysis of oxidative stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2940–2945 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzschke A., Djamei A., Bitton F. & Hirt H. A major role of the MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 pathway in ROS signalling. Mol. Plant 2, 120–137 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush S. M. & Krysan P. J. Mutational evidence that the Arabidopsis MAP kinase MPK6 is involved in anther, inflorescence, and embryo development. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2181–2191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann D. C., Lukowitz W. & Somerville C. R. Stomatal Development and Pattern Controlled by a MAPKK Kinase. Science 304, 1494–1497 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J. et al. Arabidopsis MPK6 is involved in cell division plane control during early root development, and localizes to the pre-prophase band, phragmoplast, trans-Golgi network and plasma membrane. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 61, 234–248 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M., Komis G., Muller J., Menzel D. & Šamaj J. Arabidopsis Homologs of Nucleus- and Phragmoplast-Localized Kinase 2 and 3 and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 4 Are Essential for Microtubule Organization. Plant Cell 22, 755–771 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M., Komis G., Ziemann A., Menzel D. & Šamaj J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 is involved in the regulation of mitotic and cytokinetic microtubule transitions in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 189, 1069–1083 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takáč T. & Šamaj J. Advantages and limitations of shot-gun proteomic analyses on Arabidopsis plants with altered MAPK signaling. Plant Proteomics 6, 107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. J. et al. STRING 8–a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D412–416 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A. & Götz S. Blast2GO: A comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics 2008, 619832 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord C. L. H. et al. Regulation of Arabidopsis early anther development by the mitogen-activated protein kinases, MPK3 and MPK6, and the ERECTA and related receptor-like kinases. Mol. Plant 1, 645–658 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosetsu K. et al. The MAP kinase MPK4 is required for cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 3778–3790 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X. & Zhang S. MAPK Cascades in Plant Disease Resistance Signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 245–266 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxey A. C., Yaish M. W. F., Moffatt B. A., Griffith M. & McConkey B. J. Functional Divergence in the Arabidopsis β-1,3-Glucanase Gene Family Inferred by Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Expression States. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1045–1055 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Hara-Nishimura I. & Nishimura M. Unique Defense Strategy by the Endoplasmic Reticulum Body in Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 2039–2049 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M. et al. Arabidopsis MAP Kinase 4 Negatively Regulates Systemic Acquired Resistance. Cell 103, 1111–1120 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. M. et al. Pathogen inducible voltage-dependent anion channel (AtVDAC) isoforms are localized to mitochondria membrane in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 27, 321–327 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S.-G. et al. The Arabidopsis short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 3, an ABSCISIC ACID DEFICIENT 2 homolog, is involved in plant defense responses but not in ABA biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 51, 63–73 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Brader G. & Palva E. T. Kunitz trypsin inhibitor: an antagonist of cell death triggered by phytopathogens and fumonisin b1 in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 1, 482–495 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl-Treves R., Foley R. C., Chen W. & Singh K. B. Early induction of the Arabidopsis GSTF8 promoter by specific strains of the fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 17, 70–80 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-C. et al. Characterization of a heat-stable protein with antimicrobial activity from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362, 562–567 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki K. & Ishikawa M. Identification of an Arabidopsis thaliana protein that binds to tomato mosaic virus genomic RNA and inhibits its multiplication. Virology 380, 402–411 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne P. J. et al. Heat shock 70 protein interaction with Turnip mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase within virus-induced membrane vesicles. Virology 374, 217–227 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noël L. D. et al. Interaction between SGT1 and cytosolic/nuclear HSC70 chaperones regulates Arabidopsis immune responses. Plant Cell 19, 4061–4076 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.-P., Guo Y., Sun Y., Sun D.-Y. & Wang X.-J. Influx of extracellular Ca2+ involved in jasmonic-acid-induced elevation of [Ca2+]cyt and JR1 expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Res. 119, 343–350 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Fukushige H., Hildebrand D. F. & Gan S. Evidence Supporting a Role of Jasmonic Acid in Arabidopsis Leaf Senescence. Plant Physiol. 128, 876–884 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voll L. M. et al. Loss of cytosolic NADP-malic enzyme 2 in Arabidopsis thaliana is associated with enhanced susceptibility to Colletotrichum higginsianum. New Phytol. 195, 189–202 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehl A. et al. Control of Tobacco mosaic virus Movement Protein Fate by CELL-DIVISION-CYCLE Protein48. Plant Physiol. 160, 2093–2108 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z. et al. Pathogen-secreted proteases activate a novel plant immune pathway. Nature 521, 213–216 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-G. et al. RACK1 mediates multiple hormone responsiveness and developmental processes in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2697–2708 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarsch I. K. & Ott T. Perspectives on Remorin Proteins, Membrane Rafts, and Their Role During Plant–Microbe Interactions. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 24, 7–12 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney E. C., Kandasamy M. K. & Meagher R. B. Small changes in the regulation of one Arabidopsis profilin isovariant, PRF1, alter seedling development. Plant Cell 13, 1179–1191 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Abied M. et al. Identification of plant cytoskeleton-interacting proteins by screening for actin stress fiber association in mammalian fibroblasts. Plant J. 48, 367–379 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka-Postupolska D., Clark G. & Hofmann A. Structure, function and membrane interactions of plant annexins: An update. Plant Sci. 181, 230–241 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. et al. Phosphatidic acid regulates microtubule organization by interacting with MAP65-1 in response to salt stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 4555–4576 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. et al. Phosphatidic acid mediates salt stress response by regulation of MPK6 in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 188, 762–773 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancour D. M., Dickey C. E., Park S. & Bednarek S. Y. Characterization of AtCDC48. Evidence for Multiple Membrane Fusion Mechanisms at the Plane of Cell Division in Plants. Plant Physiol. 130, 1241–1253 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S. et al. SHEPHERD is the Arabidopsis GRP94 responsible for the formation of functional CLAVATA proteins. EMBO J. 21, 898–908 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeres D. C. et al. Components of the Arabidopsis mRNA Decapping Complex Are Required for Early Seedling Development. Plant Cell Online 19, 1549–1564 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei dit Frey N. et al. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis immune-related MAPKs uncovers a role for MPK3 as negative regulator of inducible defences. Genome Biol. 15, R87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Rancour D. M. & Bednarek S. Y. In planta analysis of the cell cycle-dependent localization of AtCDC48A and its critical roles in cell division, expansion, and differentiation. Plant Physiol. 148, 246–258 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smékalová V. et al. Involvement of YODA and mitogen activated protein kinase 6 in Arabidopsis post-embryogenic root development through auxin up-regulation and cell division plane orientation. New Phytol. 203, 1175–1193 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehenwarter W. et al. Identification of novel in vivo MAP kinase substrates in Arabidopsis thaliana through use of tandem metal oxide affinity chromatography. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 12, 369–380 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu S. C. et al. MAPK target networks in Arabidopsis thaliana revealed using functional protein microarrays. Genes Dev. 23, 80–92 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang R., Jang C. J. H., Branco-Price C., Nghiem P. & Bailey-Serres J. Transient MPK6 activation in response to oxygen deprivation and reoxygenation is mediated by mitochondria and aids seedling survival in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 78, 109–122 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S.-D., Cho Y.-H., Tena G., Xiong Y. & Sheen J. Dual control of nuclear EIN3 by bifurcate MAPK cascades in C2H4 signalling. Nature 451, 789–795 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassowskat I., Böttcher C., Eschen-Lippold L., Scheel D. & Lee J. Sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase activation reprograms defense metabolism and phosphoprotein profile in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 554 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers G. J. M. et al. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases 3 and 6 Are Required for Full Priming of Stress Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21, 944–953 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Nagano A. J., Nishina M., Hara-Nishimura I. & Nishimura M. Identification of Two Novel Endoplasmic Reticulum Body-Specific Integral Membrane Proteins. Plant Physiol. 161, 108–120 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R., Kondo M., Nishimura M. & Hara-Nishimura I. A novel ER-derived compartment, the ER body, selectively accumulates a beta-glucosidase with an ER-retention signal in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 33, 493–502 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriri S. et al. Constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase versions reveal functions of Arabidopsis MPK4 in pathogen defense signaling. Plant Cell 24, 4281–4293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y. et al. MKK5 regulates high light-induced gene expression of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 54, 1217–1227 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Chen W., Jia W. & Zhang J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 5 (MKK5)-mediated signalling cascade regulates expression of iron superoxide dismutase gene in Arabidopsis under salinity stress. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 5971–5981 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Jia W. & Zhang J. AtMKK1 mediates ABA-induced CAT1 expression and H2O2 production via AtMPK6-coupled signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 54, 440–451 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takáč T. et al. Proteomic and Biochemical Analyses Show a Functional Network of Proteins Involved in Antioxidant Defense of the Arabidopsis anp2anp3 Double Mutant. J. Proteome Res. 13, 5347–5361 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluska F. et al. Root hair formation: F-actin-dependent tip growth is initiated by local assembly of profilin-supported F-actin meshworks accumulated within expansin-enriched bulges. Dev. Biol. 227, 618–632 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Blanchoin L. & Staiger C. J. Signaling to actin stochastic dynamics. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 415–440 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T. & Skoog F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- López-Bucio J. S. et al. Arabidopsis thaliana mitogen-activated protein kinase 6 is involved in seed formation and modulation of primary and lateral root development. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 169–183 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takáč T., Pechan T., Šamajová O. & Šamaj J. Integrative chemical proteomics and cell biology methods to study endocytosis and vesicular trafficking in Arabidopsis. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 1209, 265–283 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkel H. et al. ELM 2016-data update and new functionality of the eukaryotic linear motif resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D294–300 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y. et al. GPS: a comprehensive www server for phosphorylation sites prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W184–187 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 105, 121–126 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. & Mehdy M. C. A nonclassical arabinogalactan protein gene highly expressed in vascular tissues, AGP31, is transcriptionally repressed by methyl jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 145, 863–874 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks M. A. et al. Selective induction and subcellular distribution of ACONITASE 3 reveal the importance of cytosolic citrate metabolism during lipid mobilization in Arabidopsis. Biochem. J. 463, 309–317 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N. L., Heazlewood J. L., Day D. A. & Millar A. H. Lipoic acid-dependent oxidative catabolism of alpha-keto acids in mitochondria provides evidence for branched-chain amino acid catabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134, 838–848 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Yang J.-Y., Niu Q.-W. & Chua N.-H. Arabidopsis DCP2, DCP1, and VARICOSE Form a Decapping Complex Required for Postembryonic Development. Plant Cell 18, 3386–3398 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G., Todd C. D., Trovato M., Forlani G. & Funck D. Physiological implications of arginine metabolism in plants. Front Plant Sci 6, 534 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung D. Y., Vierling E. & Guy C. L. Comprehensive Expression Profile Analysis of the Arabidopsis Hsp70 Gene Family. Plant Physiol. 126, 789–800 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Xiong L., Ishitani M. & Zhu J.-K. An Arabidopsis mutation in translation elongation factor 2 causes superinduction of CBF/DREB1 transcription factor genes but blocks the induction of their downstream targets under low temperatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7786–7791 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin T. E. & Assmann S. M. Significant reduction of BiFC non-specific assembly facilitates in planta assessment of heterotrimeric G-protein interactors. Plant J. 80, 553–567 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Rancour D. M. & Bednarek S. Y. In planta analysis of the cell cycle-dependent localization of AtCDC48A and its critical roles in cell division, expansion, and differentiation. Plant Physiol. 148, 246–258 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeg C. et al. Analysis of the Arabidopsis O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase gene family demonstrates compartment-specific differences in the regulation of cysteine synthesis. Plant Cell 20, 168–185 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield J. D., Paul A.-L. & Ferl R. J. The 14-3-3 proteins of Arabidopsis regulate root growth and chloroplast development as components of the photosensory system. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 3061–3070 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyholos M. K. et al. VARICOSE, a WD-domain protein, is required for leaf blade. Development 130, 6577–6588 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Song Z. & Nikolau B. J. Reverse genetic characterization of two paralogous acetoacetyl CoA thiolase genes in Arabidopsis reveals their importance in plant growth and development. Plant J. 70, 1015–1032 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]