Abstract

Background:

Depression is not only common after menopause, but also affects postmenopausal women more than other women. Some studies show the positive effects of spiritual intervention on postmenopausal women and depressed patients. However, there is inadequate experimental data for supporting the effectiveness of such interventions.

Objectives:

This study investigated the effect of a spiritual intervention on postmenopausal depression in women referred to urban healthcare centers in Isfahan, Iran.

Patients and Methods:

A randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted on postmenopausal women referred to the healthcare centers of Isfahan. Sixty-four women with postmenopausal depression were assigned randomly into an experimental group (n = 32) and a control group (n = 32). The experimental group received eight sessions of spiritual intervention while the control group received two sessions of training on healthy diet for postmenopausal women. All subjects in the experimental group and the control group responded to the Beck’s depression inventory at the start of the study, at the end of the fourth week, and a month after the last educational session. In addition to descriptive statistics, the chi-square test, independent samples t-test and repeated measures analysis of variance were used to analyze the data.

Results:

Before the intervention, the study groups did not differ significantly in terms of mean depression scores (20.76 ± 4.61 vs. 19.58 ± 5.27, P = 0.33). However, immediately after intervention and after one month, the mean depression scores of 11.01 ± 7.85 and 11.21 ± 9.23 in the experimental group were significantly lower than the control group (19.22 ± 4.94 and 19.34 ± 4.92, respectively) (P = 0.001). In repeated measures analysis of variance, Mauchly’s test of sphericity was not significant (P = 0.672), and in the test of within-subjects effects, a significant interaction was found between the spiritual intervention and time.

Conclusions:

Spiritual intervention effectively could reduce the severity of postmenopausal depression. Considering the high prevalence of depression in postmenopausal women and the effectiveness, simplicity, and affordability of spiritual intervention, using such interventions in postmenopausal women is recommended.

Keywords: Spirituality, Women, Menopause, Depression

1. Background

Menopause is of the most critical event in middle-aged women (1, 2). Due to hormonal changes at this time, women are confronted with several physiological, psychological, and social changes (2). These changes result in significant impacts on women’s quality of life (3).

Depression is not only common after menopause (4), but also affects women more than men. It is estimated that lifetime incidence of major depressive disorder is 1.5 to 3 times more common in women than men (5). The risk of depression in postmenopausal women is 3 to 4 times more than women before menopause (6, 7). The prevalence of postmenopausal depression is different in different parts of the world (6, 8, 9). No exact information is available on the prevalence of postmenopausal depression in Iran. However, a recent study in Babol estimated that 60% of postmenopausal women had symptoms of depression (10). Although depression is a side effect of menopause, if not treated, it can cause serious complications (11).

Many strategies are available for the treatment and prevention of postmenopausal depression including medicinal treatments and cognitive-behavioral therapies. Although chemical and synthetic antidepressants are the basis for the treatment of depression (12, 13), they have numerous side effects including nausea, vomiting, fatigue, insomnia, blurred vision, dizziness, anxiety (14), decreased libido, gynecomastia, drowsiness, palpitations, headache, and skin rashes (15, 16). These side effects increased people’s tendency toward using nonpharmacological therapies (12). For many years, nonpharmacological methods such as family therapy, cognitive therapy, physical therapy, and complementary medicine have been used in the treatment of depression along with antidepressant medications (17).

Spiritual intervention is a branch of complementary medicine that seems to be useful in the treatment of psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety. According to mental health professionals, spirituality is one of the most important components and predictors of hope and psychological well-being (18, 19).

Spirituality is a multidimensional concept that includes metaphysical dimensions, meaning and purpose of life, having a mission in life, sanctity of life, underestimation of worldly values, altruism, idealism, awareness of the tragedy, and spiritual rewards (20). These dimensions play a major role in the treatment of despair, frustration, and depression. Despair is defined as the ability to deal with stressful situations. Depression is also characterized by the inability to enjoy. Focusing on control, meaning, identity, and communications, spirituality could strengthen the current psychotherapeutic methods (21) and could increase hope, happiness, and optimism in depressed people through direct and indirect effects on his or her thoughts and attitudes (22). It is believed that spiritual interventions not only help people select new purposes in life, such as growth, self-actualization, spiritual transcendence, and altruism, but also improve the mood of depressed patients through strategies such as prayer and meditation (22).

Evidence suggests that spiritual intervention has positive effects on people’s mental health. In a study on the effect of spiritual intervention, Lotfi et al. have shown the positive effects of such interventions on improvement of the quality of life and reduction of distress in mothers of children with cancer (23). In another study, Fallah et al. found that spiritual intervention significantly could promote the hope and psychological well-being in women with breast cancer (22). Steffen et al. also have reported that spirituality is a strong factor in helping women deal with menopausal symptoms (24). Several other studies also have confirmed the positive effects of spiritual intervention on postmenopausal women (25) and depressed patients (26, 27). Although not studying postmenopausal women, Ghahari et al. investigated the effects of cognitive-behavioral and spiritual-religious interventions on anxiety and depression in women with breast cancer and reported that such interventions had no effect on depression (28). Moreover, in a critical review of the effects of spiritual intervention, it was reported that there is inadequate experimental data for supporting the effectiveness of such interventions (29).

Considering the increase in women’s life expectancy in recent decades, more women experience the menopause period and its consequences such as postmenopausal depression. Therefore, depressed patients would expend higher costs for their medical treatments.

2. Objectives

Due to the controversies about the effects of spiritual intervention on postmenopausal depression, this study investigated the effect of spiritual intervention on postmenopausal depression in women referred to urban healthcare centers in Isfahan, Iran.

3. Patients and Methods

This double-blind randomized clinical trial was conducted on 64 postmenopausal women referred to the healthcare centers of Isfahan from December to March 2014.

Inclusion criteria were an age range of 45 - 60 years, the ability to speak, read, and write in Farsi, a belief in Islam, nonsmoking, having no aphasia, no recognized psychological disorder (other than depression), lacking any communication problem, receiving no hormone therapy and no antidepressant medication, cessation of menstruation for at least a year, having no history of hysterectomy and ovariectomy, receiving no formal education on spirituality, and gaining a score higher than 13 from the Beck’s depression inventory (BDI). Exclusion criteria included a participant’s decision to withdraw from the study, absence from more than one educational session, experiencing any major psychosocial crises such as death of close relatives, divorce, and hospitalization, and getting a serious illness during the study.

The sample size was calculated based on a previous study by Aghajani et al. who investigated the effect of spiritual counseling on anxiety and depression and reported that after the intervention, the mean and standard deviation of depression in the control and intervention groups were 10.87 ± 4.62 and 6.43 ± 3.04, respectively (30). Then, based on the mentioned study and considering β = 0.10, α = 0.01, S1 = 4.62, S2 = 3.04, μ1 = 10.87, and μ2 = 6.43, 24 subjects were estimated to be needed in each group. However, we recruited 32 subjects in each group to compensate for possible attrition.

A multistage sampling was performed to select the required subjects. In the first stage, a list of the governmental healthcare centers in Isfahan was prepared, and using a random-numbers table, two centers (the Imam Ali and Navab centers) were selected randomly among a total of 58 healthcare centers. Then, all existing files were examined to find families with menopausal women. In each center, 60 menopausal women initially were selected and invited to the clinic for eligibility assessment (including depression screening). Finally 32 women with inclusion criteria were selected from each healthcare center and through telephone were invited to attend a briefing session in the concerned center. If a woman did not participate in this session or decided to withdraw from the study, another eligible one was chosen randomly as a replacement. At the briefing session, all women completed the demographic questionnaire and were informed that they would be under investigation for two months, their psychological well-being would be assessed at least three times during the study, and after a short time they would be called to attend a few educational sessions. At the end of the briefing session, the 32 subjects in each healthcare center were allocated randomly into two groups. To this end, numbers from 1 to 32 were written on small pieces of papers and put in a cup, and everybody was asked to select a piece of paper and write her name on it. Accordingly, the subjects in each healthcare center were divided into two equal groups. Then, the subjects with odd and even numbers were allocated in the experimental and control groups, respectively.

Two days after the briefing session, the subjects in the experimental group were called and invited to participate in the spiritual intervention sessions. The spiritual intervention was conducted in eight sessions based on the model proposed by the American psychological association. However, the content of the sessions were modified according to Iran’s Islamic culture (22, 23). The content of spiritual intervention sessions was prepared through consultation with 10 faculty members in the nursing school and five religious experts in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Table 1).

Table 1. The Outline of the Spiritual Intervention Implemented in Postmenopausal Womena.

| Session | Title | Description of the Meeting |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction and discussion about basic concepts related to spiritual intervention | Welcome patients, introduce researcher, communicate and emphasize the positive aspects of intervention; introduce patients, include information such as age, education, occupation, etc.; definition of menopause; definition of spirituality and the role of spirituality in life; homework on how much spirituality is involved in their lives and examples of the role of spirituality and its effect on their lives; conclusion and summarizing the discussions by the subjects and feedback |

| 2 | The definition of self-consciousness and its role in life | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; definition of self-consciousness; discuss the benefits of self-consciousness and its role in life; homework about the role of self-consciousness in their life; conclusion and summarizing the discussions by the subjects and feedback |

| 3 | Familiarity with the concepts of trust and recourse and the role of them in coping with stress in life | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; definition of trust (faith) and recourse; discuss the benefits of trust and recourse and their role in life; homework about the role of trust and recourse in their lives and examples of trust and recourse; conclusion and summarizing the discussions by the subjects and feedback |

| 4 | Understanding the concept of worship and praise and the fruits of prayer and its role in the events of life | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; Definition of prayer and its importance; discuss the benefits of prayer and its role in life; express the traditions and words based on prayer; homework about the role of prayer and praise in their lives; conclusion and summarizing the discussions by the subjects and feedback |

| 5 | Understanding the effects of Eucharist and thanksgiving in life events | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; definition of thanksgiving to God and the rate of being thankful because of God’s gifts; talk about the benefits of thanksgiving and its role in life; express the traditions and speech based on thanksgiving in life; homework about the role of thanksgiving in their lives; conclusion and summarizing the discussions by subjects and feedback |

| 6 | Understanding the concept of patience | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; definition of patience; talk about the benefits of patience and its role in life; express traditions and sayings based on patience and mental relaxation in life; homework about the role of patience in their lives; conclusion and summary of discussions by subjects and feedback |

| 7 | Understanding the concept of forgiveness and consequences and its effects on life | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; Definition of forgiveness; talk about the benefits of forgiveness and its role in life; traditions and sayings to express forgiveness; homework about the role of forgiveness in their lives; conclusion and summary of discussions by subjects and feedback |

| 8 | Conclusion of meetings | Welcome, review last session, discuss and provide feedback on homework; summarize all of the meetings; get feedback from them; learn how to use teaching methods in life; thanks for their cooperation and participation |

aEvery session of meetings lasts 60 - 90 minutes time.

The spiritual intervention sessions were held for four consecutive weeks, twice a week (on Sunday and Wednesday morning), and each session lasted for 60 to 90 minutes depending on the content of each session.

Each session consisted of five parts, including greeting and recalling the content of previous session (10 - 20 minutes), introducing a spiritual strategy and discussing its effects on everyday life, mental health, and life satisfaction (about 30 minutes), a short break (10 - 15 minutes), assigning a home practice to allow each subject to immerse in the learned spiritual strategy, find its instances in their past experiences, and apply it to their present lives (5 - 10 minutes), summarizing the session’s content and giving the participants a training manual about the introduced spiritual strategy (5 - 10 minutes). To prevent absences, all subjects were called the day before each session to remind them of the time and theme of the session. All of the sessions in the experimental group were facilitated by a specialist with a doctoral degree in Islamic and spiritual issues.

Subjects in the control group were also contacted and invited to participate in two training sessions on healthy diet in postmenopausal women that were conducted by a specialist in nutrition. Facilitators of the educational sessions in both groups, facilitators of data collection, and the study subjects were unaware of the exact study objectives.

The data collection instruments included a questionnaire for demographic data (including age, religion, marital status, education level, employment status, economic status, and the last menstrual period) and the Farsi version of the BDI. The BDI is composed of 21 items on a four-point Likert scale of 0 - 3. The total score is between 0 and 63; the higher scores indicate a greater severity of depression. The Farsi version of the BDI validated by Dabson et al. and its reliability was assessed using a Cronbach’s alpha that was 0.90 (31). All subjects in the experimental and control groups answered the BDI three times (at the start of the study, at the end of the fourth week, and a month after the last educational session). Each time the subjects were required to answer the BDI individually and in a quiet room at the healthcare centers.

3.1. Ethical Considerations

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 393632). All of the participants were informed about the voluntary nature of their participation and were requested to sign an informed-consent form prior to participation. The participants also were assured of anonymity and confidentiality of the data and were reminded that they can withdraw from the study at any time. The researchers were sensitive to preserve the participants’ rights according to the Helsinki ethical declaration. This study was registered in the Iranian registry of clinical trials under the registration code IRCT2015061422733N1.

3.2. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 13. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentage, and mean and standard deviation) were calculated. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the distribution of the main quantitative variables, and the distribution was normal. The chi-square test was used to examine the relationship between dichotomous variables in the two groups. Independent samples t-test was used to compare the mean scores of quantitative variables with normal distribution in the two groups. Moreover, the repeated measures analysis of variance was used to compare the depression scores in the two groups during the three subsequent measurements. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant in all tests.

4. Results

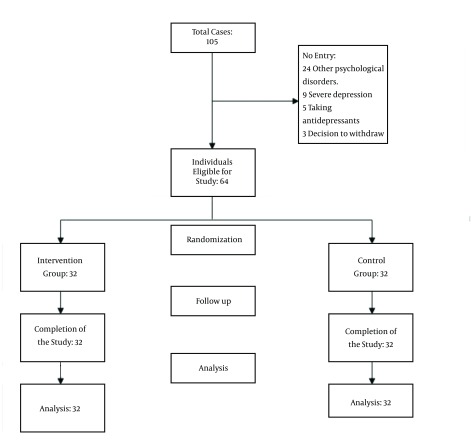

None of the subjects were excluded from analysis (Figure 1). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics (Table 2).

Figure 1. The Process of Sampling.

Table 2. The Comparison Between the Demographic Characteristics of Postmenopausal Women Receiving Spiritual Intervention and the Control Groupa.

| Variable | Intervention | Control | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marriage | 0.18 | ||

| Single | 0 | 1 (3.1) | |

| Married | 28 (87.5) | 30 (93.8) | |

| Other | 4 (12.5) | 1 (3.1) | |

| Job | 0.4 | ||

| Housekeeper | 30 (93.8) | 31 (96.9) | |

| Practitioner | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | |

| Other | 1 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Education | 0.32 | ||

| High school | 32 (100) | 31 (96.9) | |

| Collegiate | 0 | 1 (3.1) | |

| Salary, Monthly | 0.32 | ||

| < 333 dollars | 4 (12.5) | 7 (21.9) | |

| 334 - 666 dollars | 28 (87.5) | 25 (78.1) | |

| > 666 dollars | 0 | 0 | |

| History of hormone therapy | 0.5 | ||

| Yes | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.2) | |

| No | 31 (96.9) | 30 (93.8) | |

| Age | 53.62 ± 4.17 | 53.03 ± 3.87 | 0.55 |

| Duration of menopause | 5.31 ± 4.23 | 4.5 ± 3.41 | 0.35 |

aValues are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

No significant difference was found between the mean depression scores of the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.33). However, the mean depression scores of the intervention and the control groups were significantly different either immediately or one month after the study (P = 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the Mean Depression Scores in the Postmenopausal Women Receiving Spiritual Intervention and the Control Group in Three Consecutive Measurementsa.

| Time | Control Group | Intervention Group | CI 95% (Min - Max) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 19.58 ± 5.27 | 20.76 ± 4.61 | 3.00 - 0.98 | 0.33 |

| Intervention | 19.22 ± 4.94 | 11.01 ± 7.85 | −9.921 - 4.89 | 0.001 |

| After intervention | 19.34 ± 4.92 | 11.21 ± 9.23 | −9.834 - 4.37 | 0.001 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

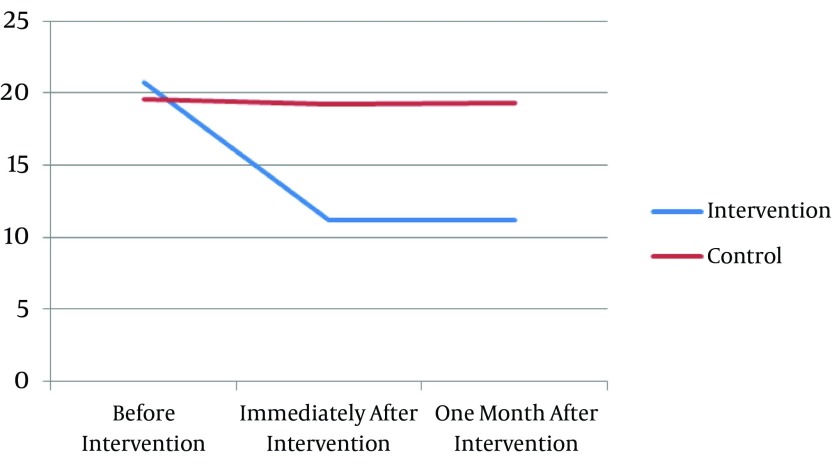

In repeated measures analysis of variance, Mauchly’s test of sphericity was not significant (P = 0.672), and in the test of within-subjects effects, a significant interaction was found between the spiritual intervention and time. In other words, a significant difference was observed between the mean depression scores of the two groups at the three measurement time points (Table 4). Figure 2 also shows the effect of the spiritual intervention in the consecutive measurements.

Table 4. Comparison of the Mean Depression Scores in the Postmenopausal Women Receiving Spiritual Intervention and the Control Group in Three Consecutive Measurementsa.

| Group | Time | F | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Month After Intervention | Immediately After Intervention | Before Intervention | |||

| Intervention | 11.21 ± 9.23 | 11.01 ± 7.85 | 20.76 ± 4.61 | 18.97 | 0.001 |

| Control | 19.34 ±4.92 | 19.22 ± 4.94 | 19.58 ± 5.27 | 0.95 | 0.397 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

Figure 2. The Mean Postmenopausal Depression in Menopausal Women Receiving Spiritual Intervention and the Control Group Over Time.

5. Discussion

At the end of this study, a significant difference was observed between the mean depression scores of the experimental and control groups. Therefore, it can be concluded that spiritual intervention was effective in reducing the severity of depression in postmenopausal women. This finding was consistent with results of several previous studies in Iran and overseas (22, 23, 26, 27, 32). However, the current study’s finding was in contrast with results of Ghahari et al. who investigated the effects of spiritual intervention on a sample of women with breast cancer (28). Such inconsistencies might be attributed to the great difference between the study populations because Ghahari et al. studied women with cancer, whereas the participants in the current study were postmenopausal women without any known organic disorders. Perhaps, many physical and psychological aftermaths of cancer significantly decreased the effects of the spiritual intervention.

Consistent with the current study, Moritz et al. (27) and Rickhi et al. (26) also have reported that spiritual interventions not only expand peoples’ attitudes toward life but also improve the mood of depressed patients through a range of religious practices and beliefs (27). It is believed that spirituality and spiritual interventions will expand peoples’ awareness of the existential and metaphysical forces in the world and lead them to feel a profound harmony and unity with the universe, which consequently promote their hope and psychological well-being (18, 19).

Spirituality seems to affect postmenopausal depression through direct and indirect mechanisms. In the direct mechanism, spirituality and spiritual interventions provide women the energy needed for adaptation with postmenopausal changes through strengthening or re-establishing the broken relationships between the person and God and other supportive resources. In indirect mechanism, spiritual interventions help the postmenopausal women make good choices in their present situation, choose a positive viewpoint toward the events, make optimistic interpretations, discover new meanings, and select new goals in their life, such as prosperity, spiritual growth, and altruism. Such new approaches to life would increase a sense of control over the crisis and restore the person to a condition of spiritual wholeness and psychological well-being (20, 22, 33-35). It also has been shown that spirituality and spiritual interventions will empower people to cope with life issues (23), help them express the anger, frustration, and fears that often are experienced during a crisis (20), reduce their feelings of guilt, depression, anxiety, and anger, and consequently increase their inner peace, hope, and sense of health (36).

People’s spirituality is not separate from their physical and psychological aspects. Spirituality, as a shield, protects a person against stress and crisis and prevents the development of mental dysfunction (36, 37). However, the positive effects of spiritual interventions are not limited to psychological well-being; it also is effective in prevention and improvement of a wide range of physical health problems and coping with chronic pain (36). Therefore, nurses’ and midwives’ familiarity with such interventions would be helpful and enable them to help their clients such as postmenopausal women effectively cope with physical and psychological symptoms of menopause.

The small sample size and relatively short time follow-up might be considered as limitations to generalize the findings of this study. Therefore, replication of similar studies with larger sample sizes and longer periods of follow-up is recommended.

In conclusion, the present study showed the effectiveness of spiritual prevention on the severity of postmenopausal depression. Considering the high prevalence of depression in postmenopausal women and the effectiveness, simplicity, and affordability of spiritual intervention, using such interventions in postmenopausal women would be helpful in prevention and treatment of postmenopausal depression. Integration of the spiritual intervention implemented in this study in the routine healthcare services of postmenopausal women is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is part of a thesis for fulfillment of a master’s degree in public health nursing. The authors would like to acknowledge the research deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for its financial support (project number: 393632). Moreover, the authors would like to thank all participants and all the authorities and healthcare workers in Imam Ali (AS) and Navab healthcare centers for their collaboration.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Zohre Shafiee: data collection writing draft, data analysis; Zahra Zandiyeh: preparing article, data analysis and supervising; Mahin Moeini: supervising and consulting; Ali Gholami: supervising and consulting.

Financial Disclosure:Authors have no disclosure.

Funding/Support:Funding support was provided by the nursing and midwifery faculty of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Wong LP, Awang H, Jani R. Midlife crisis perceptions, experiences, help-seeking, and needs among multi-ethnic malaysian women. Women Health. 2012;52(8):804–19. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.729557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parand avar N, Mosalanejad L, Ramezanli S, Ghavi F. Menopause and crisis? Fake or real: comprehensive search to the depth of crisis experienced: a mixed-method study. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6(2):246–55. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n2p246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu HY, Pan CH, Shyu YK, Han BC, Tsai PS. Effects of acupuncture on menopause-related symptoms and quality of life in women in natural menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2015;22(2):234–44. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton AH, Ninan PT. Depression or menopause? Presentation and management of major depressive disorder in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(1):PCC.08r00747. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08r00747blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman EW. Associations of depression with the transition to menopause. Menopause. 2010;17(4):823–7. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181db9f8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Nelson DB. Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):375–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dormaenen A, Heimdal MR, Wang CE, Grimsgaard AS. Depression in postmenopause: a study on a subsample of the Acupuncture on Hot Flushes Among Menopausal Women (ACUFLASH) study. Menopause. 2011;18(5):525–30. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f9f89f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timur S, Sahin NH. The prevalence of depression symptoms and influencing factors among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(3):545–51. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181cf8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delavar MA, Hajiahmadi M. Age at menopause and measuring symptoms at midlife in a community in Babol, Iran. Menopause. 2011;18(11):1213–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821a7a3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasgon N, Shelton S, Halbreich U. Perimenopausal mental disorders: epidemiology and phenomenology. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(6):471–8. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Hoseinian M. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward complementary and traditional medicine among Kashan health care staff, 2012. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(1):126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young LT. What is the best treatment for bipolar depression? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33(6):487–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford AA, Lewis S, Nutt D, Peters TJ, Cowen P, O'Donovan MC, et al. Adverse effects from antidepressant treatment: randomised controlled trial of 601 depressed individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(15):2921–31. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Goodman D, Hooper M, Hornig-Rohan M. Breast enlargement during chronic antidepressant therapy. J Affect Disord. 1997;46(2):151–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, Alshahrani A, Alnouh B, Murad MH, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–13. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2535-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dirmaier J, Steinmann M, Krattenmacher T, Watzke B, Barghaan D, Koch U, et al. Non-pharmacological treatment of depressive disorders: a review of evidence-based treatment options. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2012;7(2):141–9. doi: 10.2174/157488712800100233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang ST. Concordance of quality-of-life assessments between terminally ill cancer patients and their primary family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(1):49–57. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis B. Mediators of the relationship between hope and well-being in older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2005;14(3):253–72. doi: 10.1177/1054773805275520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni JM, Martone MG, Kerwin JF. Spirituality and psychological adaptation among women with HIV/AIDS: implications for counseling. J Couns Psychol. 2002;49(2):139. [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Souza RF, Rodrigo A. Spiritually augmented cognitive behavioural therapy. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12(2):148–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1039-8562.2004.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallah R, Golzari M, Dastani M, Akbari ME. Integrating Spirituality into a Group Psychotherapy Program for Women Surviving from Breast Cancer. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2011;4(3):141–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lotfi Kashani F, Vaziry S, Arjmand S, Mousavi SM, Hashmyh M. Effectiveness of spiritual intervention on reducing distress in mothers of children with cancer. Med Ethics. 2012;1(20):174–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steffen PR, Soto M. Spirituality and severity of menopausal symptoms in a sample of religious women. J Relig Health. 2011;50(3):721–9. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunny CA, Fraser SN. The use of complementary and alternative medicines among a sample of Canadian menopausal-aged women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(4):335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rickhi B, Moritz S, Reesal R, Xu TJ, Paccagnan P, Urbanska B, et al. A spirituality teaching program for depression: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;42(3):315–29. doi: 10.2190/PM.42.3.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moritz S, Kelly MT, Xu TJ, Toews J, Rickhi B. A spirituality teaching program for depression: qualitative findings on cognitive and emotional change. Complement Ther Med. 2011;19(4):201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghahari S, Fallah R, Bolhari J, Moosavi SM, Razaghi Z, Akbari ME. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral and spiritual-religious interventions on reducing anxiety and depression of women with breast cancer. Article in Persian]. Know Res Appl Psychol. 2012;13(4):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuck I. A critical review of a spirituality intervention. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(6):712–35. doi: 10.1177/0193945911433891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aghajani M, Afazel MR, Morasai F. The Effect of Spirituality Counseling on Anxiety and Depression in Hemodialysis Patients. J Evidence-based Care. 2014;3(4):19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dabson KS, Mohammad KP. Psychometric characteristics of Beck depression inventory–II in patients with major depressive disorder. J Rehabil. 2007;8(29):82–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolhari J, Naziri G, Zamanian S. Effectiveness of spiritual group therapy in reducing depression, anxiety, and stress of women with breast cancer. Sociol Women. 2012;3(1):85–115. [Google Scholar]

- 33.West W. Psychotherapy & spirituality: Crossing the line between therapy and religion. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnstone B, Glass BA, Oliver RE. Religion and disability: clinical, research and training considerations for rehabilitation professionals. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(15):1153–63. doi: 10.1080/09638280600955693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubey A, Agarwal A. Coping strategies and life satisfaction: Chronically ill patients’ perspectives. J Ind Acad Appl Psychol. 2007;33(2):161–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Spillers RL, Hall DL. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative's cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012;21(3):273–81. doi: 10.1002/pon.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weaver AJ, Flannelly KJ. The role of religion/spirituality for cancer patients and their caregivers. South Med J. 2004;97(12):1210–4. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146492.27650.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]