Abstract

Poor ovarian response represents an increasingly common problem. This systematic review was aimed to identify the most effective treatment protocol for poor response. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library from 1980 to October 2015. Study quality assessment and meta-analyses were performed according to the Cochrane recommendations. We found 61 trials including 4997 cycles employing 10 management strategies. Most common strategy was the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (GnRHant), and was compared with GnRH agonist protocol (17 trials; n = 1696) for pituitary down-regulation which showed no significant difference in the outcome. Luteinizing hormone supplementation (eight trials, n = 847) showed no difference in the outcome. Growth hormone supplementation (seven trials; n = 251) showed significant improvement in clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) and live birth rate (LBR) with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.13 (95% CI 1.06–4.28) and 2.96 (95% CI 1.17–7.52). Testosterone supplementation (three trials; n = 225) significantly improved CPR (OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.16–5.04) and LBR (OR 2.18; 95% CI 1.01–4.68). Aromatase inhibitors (four trials; n = 223) and dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation (two trials; n = 57) had no effect on outcome.

KEY WORDS: Assisted conception, in vitro fertilization, ovarian stimulation, poor ovarian response

INTRODUCTION

Poor ovarian response (POR) is a challenging situation in assisted reproduction. There is a lack of consensus on the definition of POR and a huge variation in treating women with previous POR.[1] However, the most common criterion to diagnose POR is retrieval of low number of oocytes despite adequate ovarian stimulation in an assisted conception cycle. The ESHRE working group on POR definition (the Bologna criteria) reached a consensus on the minimal criteria needed to define POR by the presence of two of the following three features: (i) Advanced maternal age (≥40 years) or any other risk factor for POR; (ii) a previous characterized POR cycle (≤3 oocytes with a conventional stimulation protocol); (iii) an abnormal ovarian reserve test (antral follicle count <5–7 follicles or anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) <0.5–1.1 ng/ml).[2] It was also proposed by the working group that two episodes of poor ovarian response after maximum stimulation deemed sufficient to define a patient as POR in the absence of other criteria. The suggested incidence of POR ranges from 9% to 25%.[3] Various controlled ovarian hyperstimulation protocols and strategies have been used in this group of women to improve reproductive outcome, but the success rate still remains low.

To date, there are various observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and systematic reviews reported on this subject.[4,5,6,7,8,9] However, either the studies are too specific by trying to address only one treatment strategy,[4,7,10] or they include observational studies and nonrandomized studies in their meta-analysis.[9] The aim of our systematic review is to appraise all the existing protocols applied to poor responders by including evidence generated from RCTs.

METHODS

The review was formulated using population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and design structure. Poor responders to ovarian stimulation formed the study population. All types of intervention subjected to RCTs were included in the review. The interventions were analyzed and compared with the control group used in the study. Two or more trials with identical design and interventions were analyzed by meta-analysis. Our outcome measures were number of oocytes retrieved per cycle, live birth rates (LBR), and clinical pregnancy rates (CPR).

We searched the literature on MEDLINE (1980-October 2015), EMBASE (1980-October 2015), and The Cochrane Library (2015) for relevant citations using the keywords, “poor responders, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, reduced ovarian response, diminished ovarian response, low AMH, assisted conception, and in vitro fertilization (IVF).” The reference lists of all known primary and review articles were examined to identify cited articles not captured by the electronic searches. Language restrictions were not applied. A systematic search for all RCTs was carried out. Reference lists from retrieved articles and related articles were checked for relevant studies. All studies addressing the research question and satisfying our inclusion criteria were included in the review. The review protocol was registered with the PROSPERO Registry (CRD42013004190).

Data collection and analysis

The electronic searches were scrutinized, and full manuscripts of all citations that were likely to meet the predefined selection criteria were obtained. Two review authors (Yadava Bapurao Jeve and Harish Malappa Bhandari) independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Studies which met the predefined and explicit criteria regarding population, interventions, comparison, outcomes, and study design were selected for inclusion in this review. When discrepancies occurred, they were resolved by consensus (Yadava Bapurao Jeve and Harish Malappa Bhandari). We performed meta-analysis when two or more trials were comparable in design and protocol. Data were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. For each study, the treatment effect was measured with an odds ratio (OR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes and random effect models that were presented with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Inclusion criteria

Only RCTs that used suitable definition for POR and used different therapeutic approaches for ovarian stimulation of poor responders in assisted conception were included in the study. The trials reported after publication of the Bologna criteria for poor responders were analyzed as per this criteria.[2]

Exclusion criteria

All observational studies or quasi-randomized studies and studies in which poor responders were not defined were excluded from the study.

Intervention groups

The interventions were grouped as below:

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (GnRHant) protocols

Protocols using luteinizing hormone (LH) as an adjuvant

Protocols using growth hormone (GH) as an adjuvant

Protocols using transdermal testosterone as an adjuvant

Protocols using aromatase inhibitors as an adjuvant

Protocols using dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) as an adjuvant

Protocols using recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin as an adjuvant

Natural cycle

Protocols using various other adjuvants

Various modifications to GnRH agonist (GnRHa) protocol.

Types of outcome measures

To bring uniformity in assessment, we analyzed the most relevant primary outcomes of LBR and CPR per cycle. The secondary outcome measure was the number of oocytes retrieved per cycle.

Quality and risk of bias of included studies

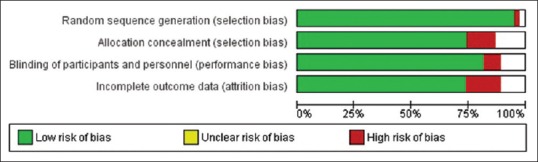

We included only RCTs in this systematic review – some were blinded and/or placebo-controlled, but others were not. Quality analysis was performed using internationally accepted Cochrane tools. GRADEpro. [Computer program on www.gradepro.org]. Version [2014]. McMaster University, 2014, was used to produce a summary of findings, tables for meta-analysis; this shows significant effects with interventions. A risk of bias table was produced using Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014, and is summarized in Figure 1. Using these tools, we have classified overall quality of evidence as moderate to high grade.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph

RESULTS

A total of 61 RCTs (4997 assisted conception cycles) were included in this study. The treatment approaches were categorized into 10 groups (as mentioned above), the most common being the use of GnRHant versus GnRHa for pituitary downregulation in 17 RCTs. The characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Different therapeutic approaches for poor responders

GnRHa versus GnRHant for pituitary downregulation: Seventeen RCTs (n = 1696) that met the criteria were subjected to meta-analysis [Figure 2]. The results suggested no significant difference in the number of oocytes retrieved (mean difference 0.09; 95% CI 0.53–0.36) and no difference in CPR with an OR of 1.24 (95% CI 0.88–1.73)

LH supplementation: Eight RCTs (n = 847) assessed the role of supplementation to ovarian hyperstimulation but found no difference in CPR (OR 1.32; 95% CI 0.93–1.87)

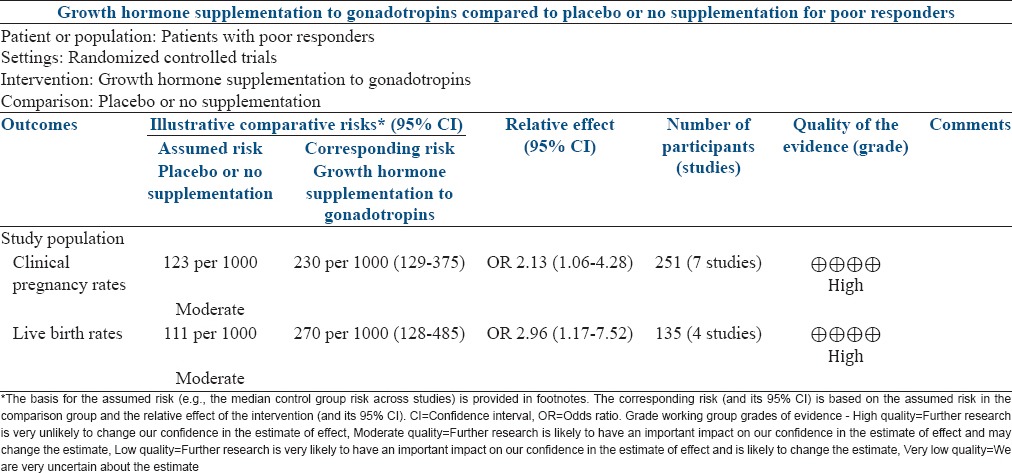

GH supplementation: None of the seven RCTs (n = 251) individually had shown benefit of GH supplementation in improving CPR, but the pooled data from these studies showed a significant improvement in CPR (OR 2.13; 95% CI 1.06–4.28). Of these, only four studies (n = 27) reported LBR and the pooled data showed significantly improved LBR (OR 2.96; 95% CI 1.17–7.52) with GH supplementation [Figure 3 and Table 2]

Testosterone supplementation: A relatively smaller number of trials tested transdermal testosterone supplementation in assisted conception cycles (three RCTs; n = 225). The meta-analysis showed significantly improved CPR (OR 2.41; 95% CI 1.16–5.04) and LBR (OR 2.18; 95% CI 1.01–4.68), but the number of oocytes retrieved was not statistically significant (mean difference 0.94; 95% CI 0.24–1.64), [Figure 4 and Table 3]

DHEA supplementation: Two RCTs (n = 99). DHEA supplementation was found to have no significant effect on the number of oocytes (mean difference 0; 95% CI − 1.07–1.07) and CPR (OR 2.10; 95% CI 0.75–5.85)

Use of aromatase inhibitors: Letrozole supplementation was used in four trials (n = 223) and the pooled data failed to find any statistically significant CPR (OR 1.28; 95% CI 0.60–2.73)

Natural cycle: The natural cycle IVF was tested by only one trial (n = 215).[11] The CPR and number of oocytes retrieved were statistically similar in both groups

Other interventions: Various authors modified the GnRHa protocols or used various supplementations such as bromocriptine, pyridostigmine, L-arginine, and low-dose aspirin which are described in Table 1. None of these interventions showed any significant improvement in outcomes.

Figure 2.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (control) versus GnRH antagonist down-regulation protocols

Figure 3.

Use of growth hormone supplement

Table 2.

Summary of findings for use of growth hormone supplementation

Figure 4.

Use of testosterone supplement

Table 3.

Summary of findings for the use of transdermal testosterone supplementation

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review updates on the evidence on various strategies to improve reproductive outcome for POR. We analyzed 61 RCTs and 4997 assisted conception cycles which were divided into 10 categories based on the interventions used.

The use of GnRHant protocol for pituitary downregulation is a commonly used approach for poor responders. GnRHant protocol offers several advantages. They cause immediate, rapid gonadotropin suppression by competitively blocking GnRH receptors in the anterior pituitary gland, thereby preventing endogenous premature release of LH and FSH. Our meta-analysis of 17 RCTs did not show any significant difference in CPR or number of oocytes retrieved with the use of GnRHant.[12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]

LH aids maintain adequate concentrations of intraovarian androgens and promote steroidogenesis and follicular growth. It has been proposed that addition of LH to ovarian stimulation protocol may benefit poor responders. Meta-analysis of eight trials[13,29,30,31,32,33] did not show significant improvement in CPR with use of recombinant LH.

GH, insulin-like growth factor-1, and GH-releasing hormone increase the sensitivity of ovaries to gonadotropin stimulation and enhance follicular development. GH enhances oocyte quality by accelerating and coordinating cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation. There are some suggestions that GH-releasing factor supplementation may improve pregnancy rates in poor responders. The pooled data from eight RCTs in this review show significantly improved CPR and LBR with GH supplementation.[13,29,36] There was no significant heterogeneity in the included studies (τ2 = 0.00, χ2 = 0.98, df = 3 [P = 0.81]; I2 = 0%). However, none of the studies had independently found any significant benefit with GH supplementation. The total numbers in the meta-analysis are small to draw any definitive conclusions.

Androgen stimulates early stages of follicular growth and increases the number of preantral and antral follicles by the proliferation of granulosa and thecal cells and reduction in granulosa cell apoptosis. It is hypothesized that positive change in microenvironment in the ovaries may lead to an increase in the number and the maturity of oocytes in poor responder group.[37] Three randomized trials[38,39,40] have tested this approach and the meta-analysis shows significant improvement in LBR and CPR.

Aromatase inhibition was proposed to improve ovarian response to FSH in poor responders. Our meta-analysis included four RCTs and failed to show any improvement in outcome with the use of aromatase inhibitors.

It is proposed that DHEA changes the follicular microenvironment by reducing hypoxic inducible factor-1, thus improving the quality of oocytes. Pooled data from 2 RCTs showed no significant difference in CPR with DHEA supplementation.[41]

Natural cycle IVF offers several advantages such as low cost and low risk of multiple pregnancies and most importantly eliminates the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Morgia et al.[11] randomized natural cycle IVF and microdose GnRHa flare along with FSH. It was found that natural cycle IVF may be as effective as IVF using controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. No further trials with this approach were found for meta-analysis.

Strengths and limitations

Our study provides most comprehensive and up-to-date review on the topic of assessing most effective treatment for poor responders and included only RCTs. We divided different approaches into 10 categories and performed meta-analysis as appropriate. Previous reviews were very specific in addressing one treatment strategy, and they failed to provide any conclusive answer. Some reviews were methodologically limited as they included observational studies and nonrandomized studies in their meta-analysis.[4,7,9]

The major limitation of this review is related to its small population size. Although some adjuvant supplementations may appear to improve ovarian response and reproductive outcome, we recognize that the numbers are small to recommend their routine use in poor responders. There was significant heterogeneity in the definition of poor responders in these trials conducted before Bologna consensus criteria were recommended.

Interpretation

Our meta-analysis showed no difference in the number of oocytes retrieved or the CPRs with use of GnRHant. The pooled data from seven studies show significantly improved CPR and LBR with GH supplementation in the previous review.[4] Our meta-analysis adds a further RCT[36] (n = 82) which results in a 48% increase in sample size. GH supplementation showed some promising results; however, the numbers are small to draw any convincing conclusion. Our results for testosterone supplementation are consistent with the results of previous meta-analyses as there were no new RCTs.[5,7] Letrozole supplementation may result in improved FSH sensitivity and concentration, but this beneficial effect was not reflected in the results. A systematic review by Bosdou et al.[7] previously showed no difference in outcome with the use of letrozole. Two more RCTs have been undertaken[37,42] since the previous review, and we added a total of 68 cycles (43%) to the sample size in our review. However, the pooled data showed no significant difference in outcome with use of letrozole. The anti-aging effect of the adrenal androgen DHEA is thought to be the mechanism to improve ovarian response. Recent meta-analysis did not show significant improvement with the use of DHEA.[9] Only two RCTs were eligible for our meta-analysis, which failed to demonstrate any benefit.

CONCLUSION

Evidence from this review suggests that GH supplementation or transdermal testosterone supplementation to assisted conception treatment cycles is associated with an improved CPR and LBR in poor responders. However, it is essential to recognize that this evidence is derived from a small number of studies; hence, we feel that the current evidence is insufficient to recommend the routine use of either of these approaches. Other treatment strategies are not found to be useful in improving clinical outcome in poor responders. We recommend that the empirical use of adjuvants should be avoided pending good quality evidence from well-designed studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patrizio P, Vaiarelli A, Levi Setti PE, Tobler KJ, Shoham G, Leong M, et al. How to define, diagnose and treat poor responders? Responses from a worldwide survey of IVF clinics. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30:581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferraretti AP, La Marca A, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L, et al. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: The Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1616–24. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keay SD, Lenton EA, Cooke ID, Hull MG, Jenkins JM. Low-dose dexamethasone augments the ovarian response to exogenous gonadotrophins leading to a reduction in cycle cancellation rate in a standard IVF programme. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1861–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.9.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyrou D, Kolibianakis EM, Venetis CA, Papanikolaou EG, Bontis J, Tarlatzis BC. How to improve the probability of pregnancy in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:749–66. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunkara SK, Pundir J, Khalaf Y. Effect of androgen supplementation or modulation on ovarian stimulation outcome in poor responders: A meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:545–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polyzos NP, Devroey P. A systematic review of randomized trials for the treatment of poor ovarian responders: Is there any light at the end of the tunnel? Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1058–61.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosdou JK, Venetis CA, Kolibianakis EM, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Zepiridis L, et al. The use of androgens or androgen-modulating agents in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:127–45. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Comadran M, Durán M, Solà I, Fábregues F, Carreras R, Checa MA. Effects of transdermal testosterone in poor responders undergoing IVF: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25:450–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narkwichean A, Maalouf W, Campbell BK, Jayaprakasan K. Efficacy of dehydroepiandrosterone to improve ovarian response in women with diminished ovarian reserve: A meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seshadri S, Sunkara SK. Natural killer cells in female infertility and recurrent miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:429–38. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgia F, Sbracia M, Schimberni M, Giallonardo A, Piscitelli C, Giannini P, et al. A controlled trial of natural cycle versus microdose gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog flare cycles in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung LP, Lam PM, Lok IH, Chiu TT, Yeung SY, Tjer CC, et al. GnRH antagonist versus long GnRH agonist protocol in poor responders undergoing IVF: A randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:616–21. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demirol A, Gurgan T. Comparison of microdose flare-up and antagonist multiple-dose protocols for poor-responder patients: A randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:481–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Placido G, Mollo A, Clarizia R, Strina I, Conforti S, Alviggi C. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist plus recombinant luteinizing hormone vs. A standard GnRH agonist short protocol in patients at risk for poor ovarian response. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:247–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devesa M, Martínez F, Coroleu B, Tur R, González C, Rodríguez I, et al. Poor prognosis for ovarian response to stimulation: Results of a randomised trial comparing the flare-up GnRH agonist protocol vs. The antagonist protocol. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:509–15. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiLuigi AJ, Engmann L, Schmidt DW, Benadiva CA, Nulsen JC. A randomized trial of microdose leuprolide acetate protocol versus luteal phase ganirelix protocol in predicted poor responders. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2531–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahraman K, Berker B, Atabekoglu CS, Sonmezer M, Cetinkaya E, Aytac R, et al. Microdose gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist flare-up protocol versus multiple dose gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol in poor responders undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection-embryo transfer cycle. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karimzadeh MA, Mashayekhy M, Mohammadian F, Moghaddam FM. Comparison of mild and microdose GnRH agonist flare protocols on IVF outcome in poor responders. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:1159–64. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1828-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu XQ, Wang WF, Tan DX. Clinical outcomes of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist used in poor ovarian responders. Wei Chung Yi Xue. 2009;4:657–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malmusi S, La Marca A, Giulini S, Xella S, Tagliasacchi D, Marsella T, et al. Comparison of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist and GnRH agonist flare-up regimen in poor responders undergoing ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marci R, Caserta D, Dolo V, Tatone C, Pavan A, Moscarini M. GnRH antagonist in IVF poor-responder patients: Results of a randomized trial. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;11:189–93. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60957-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez F, Coroleu B, Marqués L, Parera N, Buxaderas R, Tur R, et al. Comparison of ‘short protocol’ versus ‘antagonists’ with or without clomiphene citrate for stimulation in IVF of patients with ‘low response. Rev Iberoam Fert Rep Hum. 2003;20:355–60. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prapas Y, Petousis S, Dagklis T, Panagiotidis Y, Papatheodorou A, Assunta I, et al. GnRH antagonist versus long GnRH agonist protocol in poor IVF responders: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;166:43–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt DW, Bremner T, Orris JJ, Maier DB, Benadiva CA, Nulsen JC. A randomized prospective study of microdose leuprolide versus ganirelix in in vitro fertilization cycles for poor responders. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1568–71. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunkara SK, Coomarasamy A, Faris R, Braude P, Khalaf Y. Long gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist versus short agonist versus antagonist regimens in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization: A randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tazegül A, Görkemli H, Ozdemir S, Aktan TM. Comparison of multiple dose GnRH antagonist and minidose long agonist protocols in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:467–72. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0620-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian L, Lu Q, Shen H, Chen X, Han HJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist plus HMG improve the pregnancy rate of IVF-ET on poor responders. Chin J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;9:38–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang B, Sun HX, Hu YL, Chen H, Zhang NY. Application of GnRH-antagonist to IVF-ET for patients with poor ovarian response. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2008;14:423–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferraretti AP, Gianaroli L, Magli MC, D’angelo A, Farfalli V, Montanaro N. Exogenous luteinizing hormone in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for assisted reproduction techniques. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musters AM, van Wely M, Mastenbroek S, Kaaijk EM, Repping S, van der Veen F, et al. The effect of recombinant LH on embryo quality: A randomized controlled trial in women with poor ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:244–50. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrenetxea G, Agirregoikoa JA, Jiménez MR, de Larruzea AL, Ganzabal T, Carbonero K. Ovarian response and pregnancy outcome in poor-responder women: A randomized controlled trial on the effect of luteinizing hormone supplementation on in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkkanoglu M, Isikoglu M, Aydin D, Ozgur K. Clinical effects of ovulation induction with recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone supplemented with recombinant luteinizing hormone or low-dose recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin in the midfollicular phase in microdose cycles in poor responders. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:665–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruvolo G, Bosco L, Pane A, Morici G, Cittadini E, Roccheri MC. Lower apoptosis rate in human cumulus cells after administration of recombinant luteinizing hormone to women undergoing ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization procedures. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:542–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polidoropoulos N, Stefanis P, Tavaniotou M, Argyrou M, Doriza S, et al. Addition of exogenous recombinant LH in poor responders protocols: Does it really help? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;22(Suppl 1):i4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández Ramírez MJ, García-Gimeno T, Rubio JM, Montañana V, Duque C, et al. Role of LH administration during the follicular phase in women with risk of low response in ovarian stimulation with FSH and cetrorelix for IVF. Rev Iberoam Fert. 2006;5:281–90. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eftekhar M, Aflatoonian A, Mohammadian F, Eftekhar T. Adjuvant growth hormone therapy in antagonist protocol in poor responders undergoing assisted reproductive technology. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287:1017–21. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2655-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vendola K, Zhou J, Wang J, Bondy CA. Androgens promote insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor gene expression in the primate ovary. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2328–32. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.9.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goswami SK, Das T, Chattopadhyay R, Sawhney V, Kumar J, Chaudhury K, et al. A randomized single-blind controlled trial of letrozole as a low-cost IVF protocol in women with poor ovarian response: A preliminary report. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2031–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massin N, Cedrin-Durnerin I, Coussieu C, Galey-Fontaine J, Wolf JP, Hugues JN. Effects of transdermal testosterone application on the ovarian response to FSH in poor responders undergoing assisted reproduction technique – A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1204–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fábregues F, Peñarrubia J, Creus M, Manau D, Casals G, Carmona F, et al. Transdermal testosterone may improve ovarian response to gonadotrophins in low-responder IVF patients: A randomized, clinical trial. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:349–59. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiser A, Gonen O, Ghetler Y, Shavit T, Berkovitz A, Shulman A. Addition of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for poor-responder patients before and during IVF treatment improves the pregnancy rate: A randomized prospective study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2496–500. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohsen IA, El Din RE. Minimal stimulation protocol using letrozole versus microdose flare up GnRH agonist protocol in women with poor ovarian response undergoing ICSI. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:105–8. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.730569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]