Abstract

Background

Cerebral β-amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) occurs when β-amyloid (βA) is deposited in the vascular media and adventitia. It is a common pathology in the brains of older individuals and has been linked to cognitive decline but relatively little is known about the influence that CAA has on the clinical manifestation of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The aim of this retrospective analysis was to quantify the effect that CAA had on the manifestation of initial AD-related cognitive change and subsequent progression of dementia.

Methods

We analyzed neuropathological data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s dataset, performing parametric analyses to assess differences in age of progression to moderate-stage dementia.

Results

We found that individuals with both CAA burden and βA neuritic plaque burden at death had the greatest risk of earlier conversion to very mild and moderate-stage dementia, but not necessarily faster progression.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that CAA contributes to changes in early AD pathogenesis. This supports the idea that vascular change and neuritic plaque deposition are not just parallel processes but reflect additive pathological cascades that influence the course of clinical AD manifestation. Further inquiry into the role of CAA and its contribution to early cognitive change in AD is suggested.

Keywords: Alzheimer, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, vascular, cerebrovascular

Introduction

Cerebral β-amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a pathological condition in which β-amyloid (βA) is deposited in the vascular media and adventitia of cerebral blood vessels [1], is common in older adults and especially affects small vessel perfusion of brain tissue [2]. Sequela include cortical thinning [3] and infarct[4]. CAA is a known contributor to cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [5]. Two possible mechanisms linking CAA and AD include: 1) decreasing elasticity of the vessel, resulting in direct microhemorrhagic-ischemic insult to the tissue [4], and 2) blocking clearance of soluble βA thus indirectly affecting the neurons and synapses [6].

Severe CAA is more strongly related to likelihood of dementia at death than neuritic plaque or neurofibrillary tangle load [7]. CAA affects specific cognitive domains (perceptual speed and episodic memory) independent of pathological βA load [8]. However, it has recently been suggested that vascular and amyloid pathology independently predict cognitive decline.[9] Vemuri et al. used white matter lesion volume as a proxy measure of vascular change. Though this captures small infarcts associated with cerebrovascular disease, it does not directly assess the interaction of βA and the cerebrovasculature.

Despite increased interest in the role of CAA in cognitive decline, we still know little about its influence on the clinical manifestation of AD. To begin to address this gap in our knowledge, we retrospectively assessed the age of cognitive change onset, age of later stage AD, and rate of dementia progression in a large, well-characterized cohort of older adults. We hypothesized that those who had CAA (characterized neuropathologically by brain autopsy), would experience earlier AD-related cognitive change and have a faster rate of dementia progression after diagnosis.

Methods

We used the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s (NACC) dataset compiled in December 2014. The data are collected under the cooperative agreement (U01 AG016976) by member institutions approved under their respective institutional review boards. The NACC dataset includes over 30,000 subjects, most characterized longitudinally by the network of Alzheimer’s Disease Centers throughout the country using standardized reporting tools [10].

We first excluded records without neuropathology autopsy data. We then calculated age at each visit as the difference between the birth month and visit month at mid-month for each record and excluded records from individuals under 60 years of age. We also excluded subjects with a major brain infarct at autopsy (database field name NACCINF=0). Finally, we included only those individuals who were evaluated as having normal cognition at all evaluations (NORMCOG=0 and CDRGLOB=0) or were characterized as having amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCIAMEM, MCIAPLAN, MCIAPATT, MCIAPEX or MCIAPVIS =1) or probable AD as a primary cause of cognitive change (PROBAD=1 and PROBADIF=1) at any visit. We identified the last known age of normal cognition, the first known age of amnestic mild cognitive impairment or probable AD, and the first known age at which their dementia was rated at moderately severe (CDRGLOB>=2).

We categorically coded data based on neuropathologic determination of presence and severity of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and neocortical βA neuritic plaques (NP) at autopsy. We classified subjects with ‘None’ or ‘Mild’ CAA burden as CAA− (database field name NACCAMY<2). We classified subjects with ‘None’ or ‘Mild’ NP burden as NP− (NACCNEUR<2). We then grouped subjects based on the classifications: no significant CAA or NP burden (CAA−/NP−), no significant CAA burden but significant NP burden (CAA−/NP+), significant CAA burden with no NP burden (CAA+/NP−), significant CAA and NP burden (CAA+/NP+).

Group demographics were compared using standard parametric and nonparametric tests as appropriate. CAA and NP burden were compared using Spearman’s rank order test. Because the exact age of cognitive change onset and age of moderate-stage dementia were either left- (patients had already experienced the events at their first visit), interval- (event occurred between visits), or right-censored (events were not observed by the last follow-up visit), we assessed differences in age of cognitive change onset and age of moderate-stage dementia based on presence of neuropathology using parametric regression with various distributions: exponential, gamma, log-logistic, log-normal, and Weibull selected using Bayesian Information Criterion. This allowed us to take advantage of the larger, censored dataset. The models included main effects of sex, race (non-white vs. white), education, hypertension (active or remove vs. none), and hypercholesterolemia (active or remove vs. none) and included two-way interactions. Post-hoc comparisons across groups were conducted by regression analysis. We also performed an analysis confined to subjects who had CDR 0.5 initially or showed CDR 0.5 during follow-up visits, and estimated the time of progression from CDR 0.5 to CDR ≥ 2. By definition, this time to progression was the difference in the corresponding censored ages.

To ease communication of the analyses, we use the following notations. We let

T1 = the last known age of normal cognitive status;

T2 = the first known age of cognitive status change;

T3 = the last known age of CDR < 2;

T4 = the first known age of CDR ≥ 2.

Age of cognitive status change was interval-censored if both T1 and T2 were available; was right-censored if T1 was available but T2 was missing; or was left-censored if T2 was available but T1 was missing. Age of moderate dementia onset can be interpreted in the same manner using T3 and T4 instead of T1 and T2.

Building on this notation, we also calculated a time of progression from available information. We let

T5 = T3 − T2, the time elapsed in early-stage AD;

T6 = T4 − T1, the time elapsed from normal cognition to moderate-stage dementia if T1 and T4 were available (i.e., cognitive status change and moderate dementia were both interval censored).

Alternatively, T6 was coded as missing if T4 was missing (right-censored age of moderate-stage dementia). For observations with T4 available but missing T1, we computed T6 = T4 − T2 as a proxy measure. As the analyses for age of cognitive change and age of moderate-stage dementia, the (T5, T6) pairs were used in parametric regression to incorporate interval- and right-censored observations. When T2 = T3 and T6 was not missing, we set T5 = 0.1 to avoid the observations being excluded from analysis.

Results

Our sample included only those with normal cognition, or AD-related cognitive change (n=1439), excluding individuals who reverted to normal status at any visit. We excluded 25 subjects with no CAA classification, leaving n=1414. The mean follow-up period of these 1414 subjects was 3.0 years (standard deviation [SD] 2.1). Table 1 summarizes dementia stage progression of our sample. An additional 22 subjects without information on education, hypertension, and/or hypercholesterolemia were further excluded from the regression analyses, resulting in a sample size of N=1392.

Table 1.

Numbers of subjects broken down by their cognitive status at the initial visit and the status at the last follow-up visits

| Status at last follow-up visit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial status | Total | Normal | CDR 0.5 or 1 |

CDR ≥ 2 |

| Normal (CDR 0) | 238 | 193 | 39 | 6 |

| Early-stage dementia (CDR 0.5 or 1) |

720 | 0 | 186 | 534 |

| Moderate-stage dementia (CDR ≥ 2) |

456 | 0 | 0 | 456 |

| Total | 1414 | 193 | 225 | 996 |

Age of AD-related Cognitive Change Onset

Table 2 presents demographic data for the sample and notes the number of missing values in each descriptor. Individuals with CAA+/NP+ had an earlier age of enrollment and earlier age of death (Table 2, p<0.001). Race was marginally significantly different between groups, largely driven by a higher proportion of non-white individuals classified as CAA+/NP−(X2(3)=6.2, p=0.10). As expected, individuals with an APOE e4 allele were more likely to be categorized as having significant CAA or NP burden (X2 (3)=150.6, p<0.001). CAA burden was only moderately correlated with NP burden, even after controlling for age of death and APOE e4 carrier status (rho=0.36, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Group demographics for the sample.

| CAA− / NP− n=257 |

CAA− / NP+ n=651 |

CAA+ / NP− n=37 |

CAA+ / NP+ n=469 |

Number of missing values |

sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Enrollment, y |

83.9 (8.6) | 80.7 (8.4) | 85.6 (7.5) | 79.5 (8.2) | 0 | F(3,1410)=18. 9, p<0.001 |

| Age at Death, y | 87.0 (8.8) | 84.0 (8.3) | 90.0 (7.5) | 83.0 (8.1) | 0 | F(3,1410)=17. 8, p<0.001 |

| Female, n(%) | 132 (51.4) |

308 (47.3) |

18 (48.7) | 212 (45.2) | 0 | X2(3)=2.6, p=0.47 |

| Education, y | 15.1 (3.3) | 15.2 (3.1) | 15.1 (2.8) | 14.9 (3.3) | 10 | F(3,1401)=0.8 , p=0.48 |

| Race, n(%) | 0 | |||||

| White | 246 (95.7) |

621 (95.4) |

32 (86.5) | 444 (94.7) | -- | X2(3)=6.2, p=0.10 |

| Black | 6 (2.3) | 24 (3.7) | 3 (8.1) | 20 (4.3) | -- | |

| Other | 5 (2.0) | 6 (0.9) | 2 (5.4) | 5 (1.0) | -- | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, n(%) |

12 (4.7) | 23 (3.5) | 1 (2.7) | 20 (4.3) | 5 | X2(3)=0.9, p=0.82 |

| Hypertension, n(%) |

146 (57.5) |

320 (49.2) |

21 (56.8) | 217 (46.4) | 4 | X2(3)=9.0, p=0.03 |

| Hypercholesterole mia, n(%) |

115 (45.1) |

284 (43.9) |

22 (61.1) | 215 (46.2) | 10 | X2(3)=4.3, p=0.23 |

| ApoE4 Carrier, n(%) |

43 (18.6) | 274 (49.4) |

17 (54.8) | 277 (69.1) | 195 | X2(3)=150.6, p<0.001 |

| CAA Classification at autopsy, n(%) |

0 | |||||

| None, Unknown |

185 (72.0) |

280 (43.0) |

-- | -- | -- | |

| Mild | 72 (28.0) | 371 (57.0) |

-- | -- | -- | |

| Moderate | -- | -- | 31 (83.8) | 282 (60.1) | -- | |

| Severe | -- | -- | 6 (16.2) | 187 (39.9) | -- | |

| CERAD neuritic plaque density, n(%) |

0 | |||||

| None | 159 (61.9) |

-- | 14 (37.8) | -- | -- | |

| Sparse | 98 (38.1) | -- | 23 (62.2) | -- | -- | |

| Moderate | -- | 194 (29.8) |

-- | 86 (18.3) | -- | |

| Frequent | -- | 457 (70.2) |

-- | 383 (81.7) | -- |

Values are frequencies or means (standard deviation), except when noted.

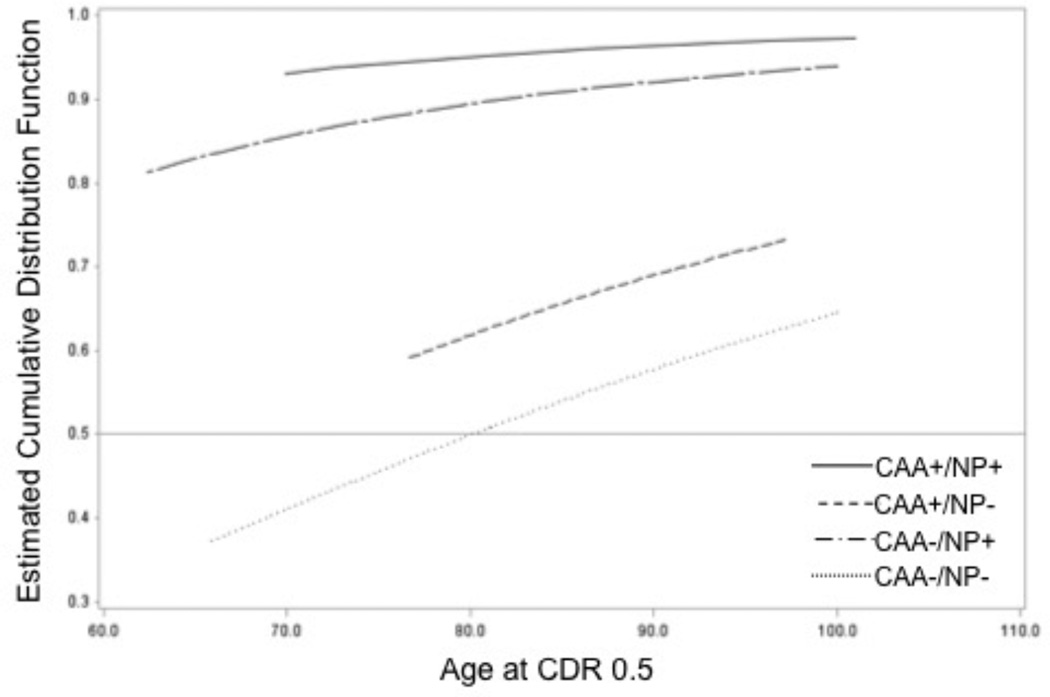

The estimates for median age of cognitive change onset were before 62.4y (CAA−/NP+), before 69.9y (CAA+/NP+), before 76.7y (CAA+/NP−), and 80.4y (CAA−/NP−). See Figure 1 for the cumulative probability plots of age of cognitive change. Only the CAA−/NP− curve intersects at 50% cumulative probability, at 80.4y. Because more than half observations were left-censored for all other groups (i.e. most subjects had already experienced cognitive change before enrollment), their curves do not reach 50% cumulative probability. Thus the reported, estimated median age of cognitive change and the intersections at 0.5 cumulative probability are interpolations and likely to be skewed.

Figure 1.

This plot shows the cumulative probability of cognitive change against age for each of our neuropathologic classifications: no significant neuritic plaque (NP) or cerebral amyloid angiopathy burden (CAA−/NP−, black line), no significant CAA burden but significant NP burden (CAA−/NP+, blue line), significant CAA burden with no NP burden (CAA+/NP−, green line), significant CAA and NP burden (CAA+/NP+, red line). The light gray horizontal line at denotes at least 50% of individuals experiencing cognitive change. Note how the CAA+/NP+ and CAA−/NP+ groups have high likelihood for experiencing cognitive change even at an early age.

We then tested age of cognitive change onset against our neuropathologic classification groups, accounting for sex, race, education, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Women (Hazard Ratio=0.40, p<0.001) and those with more education were more likely to experience cognitive change onset at a later age (HR=0.90, p<0.001). Non-white subjects seemed to have greater risk of cognitive change at an earlier age (HR = 2.68, p=0.04), but this effect should be interpreted with caution due to low sample size. Subjects with hypercholesterolemia also tended to be at risk for earlier age of cognitive change onset (HR=1.65, p=0.005) whereas subjects with hypertension showed lower risks than their counterpart (HR = 0.69, p = 0.03). We found that after accounting for sex, race and education, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia, both CAA status (X2 (1)=7.7, p=0.006) and NP status (X2 (1)=55.1, p<0.001) were significant factors affecting age of cognitive change. The post hoc comparisons indicated that CAA+/NP+ individuals were more likely to experience cognitive change earlier than those with NP+ alone (HR=2.0, p=0.006) or CAA+ alone (HR=13.9, p<0.0001), and much more likely to experience cognitive change than those with no little or no neuropathological burden (CAA−/NP−, HR=19.2, p<0.001); individuals with NP+ alone had higher risks of cognitive change than those with CAA+ alone (HR=6.8, p<0.0001) and CAA−/NP− individuals (HR=9.4, p<0.0001); but no significant difference between those with CAA+ alone and those with CAA−/NP− (HR=1.4, p=0.39). These post hoc comparisons revealed an order of risk for earlier cognitive change: CAA+/NP+, CAA−/NP+, and followed by NP− (either with or without CAA+).

Age of Moderate-stage Dementia

Our next question was whether individuals with CAA experience more rapid decline. In order to capitalize on the large NACC dataset, we first investigated estimated age of conversion to moderate-stage dementia. This does not directly address rate of progression but, coupled with age of onset, provides some estimate of progression.

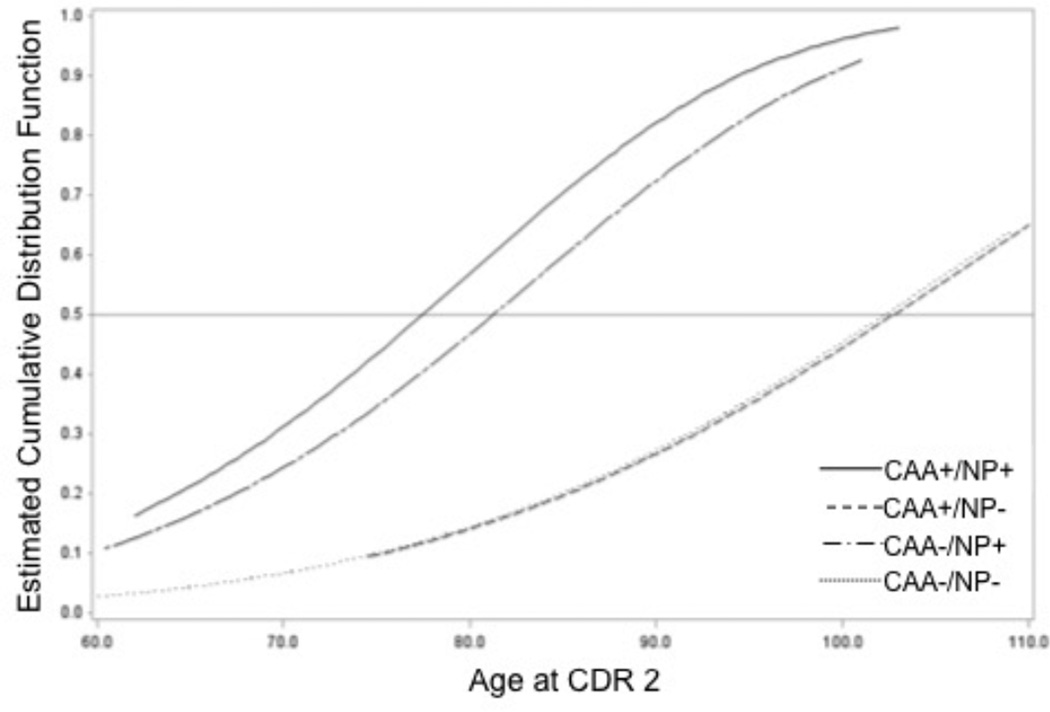

The estimates for median age of moderate-stage dementia were 77.5 y (CAA+/NP+), >110.0 y (CAA+/ NP−), 81.4 y (CAA−/NP+), and >104 y (CAA−/NP). Figure 2 shows the estimated cumulative probabilities vs. age. Note there were only 4 observations with last known age > 100 y for CAA+/NP− and CAA−/NP− groups. Thus the reported, estimated median age of conversion to moderate-stage are interpolations.

Figure 2.

This plot shows the cumulative probability of moderate-stage dementia classification against age for each of our neuropathologic classifications: no significant neuritic plaque (NP) or cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) burden (CAA−/NP−, black line), no significant CAA burden but significant NP burden (CAA−/NP+, blue line), significant CAA burden with no NP burden (CAA+/NP−, green line), significant CAA and NP burden (CAA+/NP+, red line). The light gray horizontal line at denotes at least 50% of individuals experiencing moderate-stage dementia. Note again how the CAA+/NP+ and CAA−/NP+ groups have high likelihood for experiencing earlier classification as moderately demented.

We then tested moderate-stage dementia classification against our neuropathological classification groups, accounting for sex, education, race, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. As with our first analysis, we found that being male (HR=1.29, p=0.0007), non-white (HR=1.52, p=0.007), and having hypercholesterolemia (HR=1.23, p=0.007) were associated with greater risk of earlier of moderate-stage dementia classification. More years of education (HR=0.95, p<0.0001) and having hypertension (HR=0.80, p=0.003) were associated with a lower likelihood of early moderate-stage dementia classification. After accounting for sex, race education, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia, both CAA status (X2 (1)=13.6, p=0.0002) and NP status (X2 (1)=119.8, p<0.0001) were significant factors influencing age of moderate-stage dementia classification. As in the analysis of age of cognitive change onset, the post hoc comparisons indicated that CAA+/NP+ individuals were at a marginally greater risk of early conversion to moderate-stage dementia than those with NP+ alone (HR=1.04, p=0.0005), and more robust risk versus those with CAA+ alone (HR=1.29, p<0.0001), or those with little or no neuropathological burden (CAA−/NP−, HR=1.29, p<0.0001). Individuals with NP+ alone had a greater risk of earlier conversion to moderate-stage dementia than those with CAA+ alone (HR=1.24, p=0.0004) and CAA−/NP− individuals (HR=1.24, p<0.0001); but those with CAA+ alone were not at more risk than those with CAA−/NP− (HR=1.01, p=0.99).

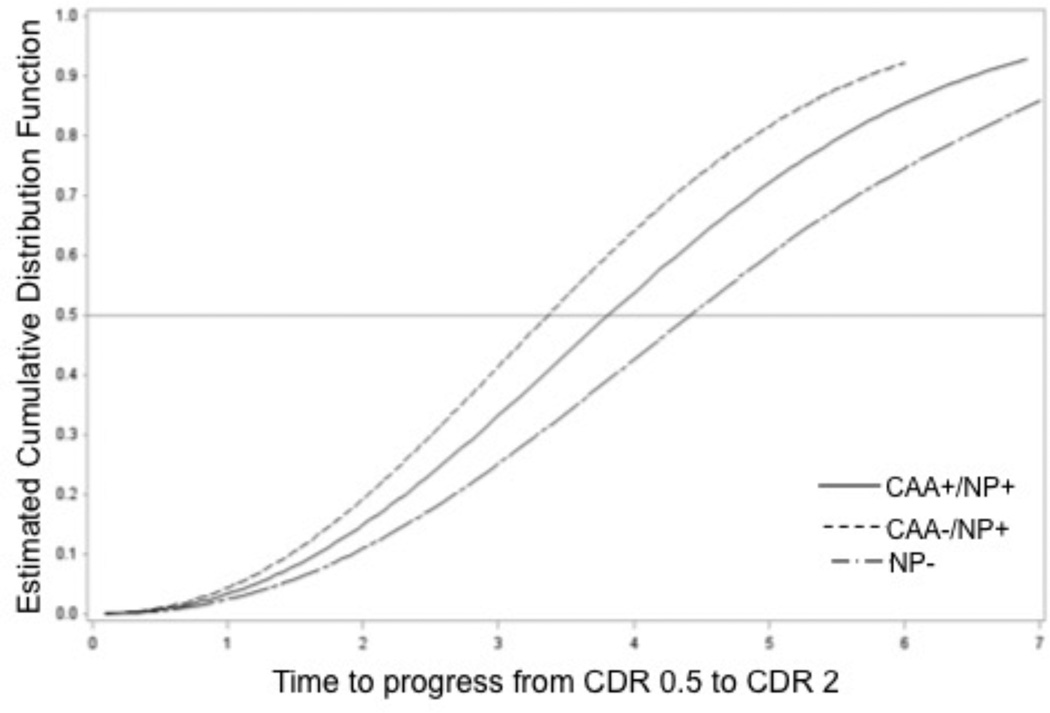

Rate of Dementia Progression

Table 3 presents demographic data for the direct comparison of rates of dementia progression (n=290). We combined subjects classified as CAA+/NP− with CAA−/NP− due to low numbers of subjects (n=8). The overall differences across the 3 groups were marginally significant (p=0.051). Post hoc comparisons indicated a trend of high risk of faster progression in CAA−/NP+ vs. all NP− subjects (HR=1.85, p=0.022 > 0.05/3 by Bonferroni correction). Other comparisons were not significant: CAA−/NP+ vs. CAA+/NP+ subjects (HR=1.33, p=0.14), and CAA+/NP+ vs. NP− subjects (HR=1.39, p=0.24). The conclusions remained the same when covariates of sex, race, education, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia were adjusted.

Table 3.

Group demographics for rate of progression from very mild (Clinical Dementia Rating = 0.5) to moderate dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating = 2).

| CAA− / NP− n=54 |

CAA− / NP+ n=139 |

CAA+ / NP− n=8 |

CAA+ / NP+ n=89 |

No. missing values |

Sig † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Time of Dementia Progression, y |

4.5 † | 3.4 | 4.5† | 3.9 | -- | X2(2)=5.94, p=0.051 |

| Female, n (%) | 24 (44.4) | 58 (41.7) | 3 (37.5) | 33 (37.1) | 0 | X2(2)=0.75, p=0.69 |

| Education, y | 15.0 (3.4) | 15.7 (2.8) | 15.3 (2.3) | 15.6 (3.1) | 1 | F(2,354)=1.15, p=0.32 |

| Hypertension, n(%) | 32 (60.4) | 73 (52.5) | 4 (50.0) | 42 (47.2) | 1 | X2(2)=2.04, p=0.36 |

| Hypercholesterole mia, n(%) |

20 (37.7) | 60 (43.5) | 5 (71.4) | 50 (56.2) | 3 | X2(2)=4.38, p=0.11 |

| CAA Classification at autopsy, n (%) |

||||||

| None, Unknown | 39 (72.2) | 65 (46.8) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Mild | 15 (27.8) | 74 (53.2) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Moderate | -- | -- | 8 (100) | 52 (58.4) | -- | |

| Severe | -- | -- | 0 (0) | 37 (41.6) | -- | |

| CERAD neuritic plaque density, n(%) |

||||||

| None | 26 (48.1) | -- | 0 (0) | -- | -- | |

| Sparse | 28 (51.9) | -- | 8 (100) | -- | -- | |

| Moderate | -- | 51 (36.7) | -- | 25 (28.1) | -- | |

| Frequent | -- | 88 (63.3) | -- | 64 (71.9) | -- |

Values are frequencies or means (standard deviation).

CAA+ / NP− group was combined with CAA−/NP− due to few observations.

Discussion

We used a large cohort of individuals with neuropathologic characterization to explore the relationship of CAA to cognitive change onset and rate of dementia progression in the absence of major infarcts. Our goal was to determine if CAA meaningfully contributed to an earlier onset or faster progression of AD-related dementia. We found that having significant loads of CAA and NP posed the greatest risk for cognitive change at an earlier age. However, for those with CAA, the risk of conversion to moderate-stage dementia was only slightly greater than those without. Our direct assessment of progression in a smaller sample found that those with NP but without significant CAA were at the greatest risk for faster progression. In fact, those who were both CAA+ and NP+ exhibited slightly slower progression than those who were only NP+.

Our findings support the relationship between CAA and early cognitive change compared to those without neuropathologic burden [8], while de-emphasizing its role in explaining the speed of dementia progression. We speculate that evidence of CAA may have a greater impact early, possibly through reducing cognitive reserve, a construct that explains maintained cognition despite neuropathologic brain damage [11]. Indeed, previous studies suggest that conditions associated with vascular compromise (e.g. diabetes) result in earlier but slower decline [12, 13]. It is also possible that after reaching a certain threshold of vascular β-amyloid clearance, non-vascular tissue instead become the primary accumulation site [14]. Aggregation-prone peptides such as βA exhibit different kinetics for deposition (or “seeding”) and growth [15], and often eventually plateau in concentration [10]. Once in vessels, CAA-related effects on blood flow could slow the clearance of extracellular proteins such βA, increasing their concentration in the parenchyma [16]. The importance of blood vessels in βA clearance is underscored by studies using βA immunotherapy agents – when βA is cleared from the parenchyma, deposition is increased in perivascular pathways [17]. Potential saturation of the vessel may have consequences for βA clearance as a treatment avenue [18].

Though intriguing, this analysis has several limitations to consider. The cohort was well characterized over a long period under highly standardized methods across many sites. Despite this, there could be differences based on demographics of the regional subject population. Our sample was predominantly white, non-Hispanic, limiting generalization to the broader population. Finally, thought the NACC dataset is among the largest longitudinal datasets of AD and cognitive aging characterization in the world, it is subject to selection bias. Our results are likely influenced by the socioeconomic and emotional factors involved in who elects to enter the study and when. This can be most clearly seen in our cumulative probability functions and estimated median ages of conversion. Several of these ages are inconsistent with clinical presentation. Most subjects had already experienced cognitive change, 83% left-censored data. Thus, estimates of conversion age are interpolations and should be interpreted with caution. Further, the majority of individuals who entered the study who ultimately proved to have significant neuritic plaque burden, with or without CAA, were younger. This may reflect a younger population seeking entry in clinical trials [19].

Our findings support the belief that CAA contributes to significant changes in early AD pathogenesis. Importantly, the results support that vascular amyloidosis and neuritic plaque deposition are not just parallel processes but additive pathological cascades that influence the course of clinical change. Cerebral amyloid deposition may shift dementia onset and conversion to moderate-dementia to a younger age. These findings require further investigation into the relationship of CAA and neurotic plaque burden on the clinical expression of AD.

Figure 3.

This plot shows the estimated cumulative probability of time to progress from early-stage to moderate-stage dementia classification based on neuropathologic classification at autopsy: no significant neuritic plaque (NP) or cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) burden (CAA−/NP− or CAA+/NP−, blue line), no significant CAA burden but significant NP burden (CAA−/NP+, green line), significant CAA and NP burden (CAA+/NP+, red line). The light gray horizontal line at denotes at least 50% of individuals transitioning to moderate-stage dementia.

References

- 1.Grinberg LT, Thal DR. Vascular pathology in the aged human brain. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119:277–290. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0652-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickstein DL, Walsh J, Brautigam H, Stockton SD, Jr, Gandy S, Hof PR. Role of vascular risk factors and vascular dysfunction in alzheimer's disease. Mount Sinai J Med. 2010;77:82–102. doi: 10.1002/msj.20155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villeneuve S, Reed BR, Madison CM, Wirth M, Marchant NL, Kriger S, Mack WJ, Sanossian N, DeCarli C, Chui HC, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Vascular risk and abeta interact to reduce cortical thickness in ad vulnerable brain regions. Neurology. 2014;83:40–47. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dierksen GA, Skehan ME, Khan MA, Jeng J, Nandigam RN, Becker JA, Kumar A, Neal KL, Betensky RA, Frosch MP, Rosand J, Johnson KA, Viswanathan A, Salat DH, Greenberg SM. Spatial relation between microbleeds and amyloid deposits in amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:545–548. doi: 10.1002/ana.22099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aisen PS, Schneider LS, Sano M, Diaz-Arrastia R, van Dyck CH, Weiner MF, Bottiglieri T, Jin S, Stokes KT, Thomas RG, Thal LJ. High-dose b vitamin supplementation and cognitive decline in alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1774–1783. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weller RO, Boche D, Nicoll JAR. Microvasculature changes and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in alzheimer's disease and their potential impact on therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:87–102. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0498-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuropathology Group. Medical Research Council Cognitive F, Aging S. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in england and wales. Neuropathology group of the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study (mrc cfas) Lancet. 2001;357:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Wang Z, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy pathology and cognitive domains in older persons. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:320–327. doi: 10.1002/ana.22112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Knopman DS, Preboske GM, Kantarci K, Raman MR, Machulda MM, Mielke MM, Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Rocca WA, Roberts RO, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Vascular and amyloid pathologies are independent predictors of cognitive decline in normal elderly. Brain. 2015;138:761–771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, Wu J, Hubbard JL, Koepsell TD, Morris JC, Kukull WA. The national alzheimer's coordinating center (nacc) database: The uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:448–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanz C, Andrieu S, Sinclair A, Hanaire H, Vellas B. Diabetes is associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline in alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1359–1366. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd80e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruandet A, Richard F, Bombois S, Maurage CA, Deramecourt V, Lebert F, Amouyel P, Pasquier F. Alzheimer disease with cerebrovascular disease and vascular dementia: Clinical features and course compared with alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2009;80:133–139. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.137851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibata M, Yamada S, Kumar SR, Calero M, Bading J, Frangione B, Holtzman DM, Miller CA, Strickland DK, Ghiso J, Zlokovic BV. Clearance of alzheimer's amyloid-ss(1-40) peptide from brain by ldl receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1489–1499. doi: 10.1172/JCI10498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paravastu AK, Qahwash I, Leapman RD, Meredith SC, Tycko R. Seeded growth of beta-amyloid fibrils from alzheimer's brain-derived fibrils produces a distinct fibril structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7443–7448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812033106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thal DR, Grinberg LT, Attems J. Vascular dementia: Different forms of vessel disorders contribute to the development of dementia in the elderly brain. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:816–824. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Nicoll JA. Consequence of abeta immunization on the vasculature of human alzheimer's disease brain. Brain. 2008;131:3299–3310. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bates KA, Verdile G, Li QX, Ames D, Hudson P, Masters CL, Martins RN. Clearance mechanisms of alzheimer's amyloid-beta peptide: Implications for therapeutic design and diagnostic tests. Molecular Psychiatr. 2009;14:469–486. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating alzheimer disease research recruitment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:1–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]