Abstract

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) mediate molecular transport between the nucleus and cytoplasm in eukaryotic cells. Tethered within each NPC lie numerous intrinsically disordered proteins known as FG nucleoporins (FG Nups) that are central to this process. Over two decades of investigation has converged on a view that a barrier mechanism consisting of FG Nups rejects non-specific macromolecules while promoting the speed and selectivity of karyopherin (Kaps) receptors (and their cargoes). Yet, the number of NPCs in the cell is exceedingly small compared to the number of Kaps, so that in fact there is a high likelihood the pores are always populated by Kaps. Here, we contemplate a view where Kaps actively participate in regulating the selectivity and speed of transport through NPCs. This so-called “Kap-centric” control of the NPC accounts for Kaps as essential barrier reinforcements that play a prerequisite role in facilitating fast transport kinetics. Importantly, Kap-centric control reconciles both mechanistic and kinetic requirements of the NPC, and in so doing potentially resolves incoherent aspects of FG-centric models. On this basis, we surmise that Kaps prime the NPC for nucleocytoplasmic transport by fine-tuning the NPC microenvironment according to the functional needs of the cell.

Keywords: FG Nucleoporin, Karyopherin, Nuclear pore complex, Nucleocytoplasmic transport

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells maintain order and function by the exchange of macromolecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Every second, mixed within a rich biological milieu, essential proteins, RNAs and metabolites impinge, crowd and translocate across the nuclear envelope.1 This process is termed nucleocytoplasmic transport, which proceeds through aqueous channels known as nuclear pore complexes (NPCs).2

The modus operandi that facilitates the selectivity and speed of signal-specific cargoes through NPCs is one that continues to fascinate and confound in equal measure. Despite bearing a 50 nm-diameter central channel, only molecules smaller than 40 kDa or 5 nm in size can passively diffuse in an unhindered manner through the NPC, whereas larger macromolecules are excluded.3 In contrast, rapid transport is accorded to nuclear transport receptors such as karyopherins (Kaps, also known as importins and exportins) that identify, bind and shuttle large specific cargoes that would otherwise be rejected by the NPC in the absence of Kaps.4 Kaps distinguish essential cargoes such as transcription factors from other non-essential proteins based on peptide sequences known as nuclear localization or nuclear export signals (NLS or NES).5,6 This is typified by the import receptor Kapβ1 (Impβ; 100 kDa),7 which binds NLS-cargoes via an adaptor Kapα (Impα; 60 kDa) to altogether form transport-competent complexes that are many times more massive than the putative 40 kDa size exclusion limit of the NPC. It is even more perplexing how large transport complexes appear to surpass passive diffusion rates when traversing the NPC.8

FG-centric Barriers

The functional constituents of the NPC consist of intrinsically disordered proteins that contain large numbers of phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats known as FG nucleoporins (FG Nups).9 FG Nups bear multiple FG-repeat motifs that are essential for transport selectivity because they exert multivalent binding interactions with Kaps.10-12 Over 200 FG Nups are physically constrained to the inner walls of the NPC by tethering domains, upon which disordered FG domains (typically 200 – 700 aa in length) emanate to explore the aqueous central channel.13 Hence, each tether point defines the relative position, surface density, and collective FG Nup morphology inside the NPC.14 On this basis, the FG Nups are reasoned to manifest barrier-like properties that guard against non-specific proteins while simultaneously providing selective access to Kaps that bind to FG-repeats.

The ongoing debate about NPC function largely stems from an inability to directly resolve FG Nup structure and dynamics inside the NPC. So far, FG Nup behavior has been inferred from indirect approaches such as immunolabelling transmission electron microscopy,15 various fluorescence microscopies,16,17 and most recently mechanical measurements obtained by indentation-based atomic force microscopy.18 Therefore, any information regarding the structure and function of the NPC barrier is still largely phenomenological and based in part on the following rationale:

The FG Nups adopt collective arrangements that exert barrier-like functionality.

Specific Kap-FG interactions ensure NPC transport selectivity; insufficient binding leads to barrier rejection.

High mobility ensues from specific Kap-FG interactions.

Inevitably, in vitro-derived FG Nup materials, such as supramolecular hydrogel meshworks,19,20 and molecular brushes,21,22 or their proposed combinations23 dominate how we treat the FG Nups as the key barrier components, as evident in artistic depictions of the NPC. Regardless, what is clear is that the FG Nups – being intrinsically disordered – are sensitive to experimental design in vitro, and can adopt different morphologies at different length scales with diverse structures, characteristics and properties.24 We refer the interested reader to ref. 24 for a recent review on the matter.

Yet, insofar as such “FG-centric” models are able to rationalise mechanistic NPC function, explanations of fast transport kinetics remain vague and even paradoxical. At the structural level, each Kapβ1 molecule consists of approximately 10 hydrophobic grooves that can all potentially bind FG-repeats.10-12 Moreover, the FG Nups contain between 5 to around 50 FG-repeats25 that can simultaneously bind individual Kaps at multiple contact points. Hence, Kap-FG Nup binding is characterized by highly multivalent interactions,26,27 which are recognized to enhance stability and specificity due to strong binding avidity.28 As raised by Tetenbaum-Novatt et al,29 the known sub-μM Kapβ1-FG domain binding affinities11,30-32 may “ensure” NPC transport selectivity but contradict the rapid ∼5 ms dwell times of nucleocytoplasmic transport cargoes in vivo33 and in vitro.34-36 It is intriguing that even FG Nup-coated nanopores are able to recapitulate both the selectivity and speed of Kapβ1 translocation with a dwell time of ∼2.5 ms,37 in close agreement with NPC transport values. What might promote fast translocation in the NPC instead of slowing it down?

Selectivity, Speed and Space: The Microenvironment Matters

In fact, the NPC problem conflates specific binding, translocation speed and nanoscale spatial constraints. As the sole conduit that connects the cytoplasm and the nuclear interior, each NPC is above all a major intracellular transport hub that regulates the traffic of essential nucleocytoplasmic cargoes ranging from signal transducing proteins38 to RNAs.39 Not surprisingly, up to 100 Kaps occupy the pore at steady state at cellular Kap concentrations of ∼10 μM.40-42 With 20 different Kaps shuttling diverse cargoes through the NPC,43 it would be reasonable to expect that a priori the pore is overcrowded and that any remaining space within is very limited. This makes it difficult to assign to each Kap the functional role of a “key” that unlocks the FG Nup “gate.” In part, this is exacerbated by promiscuous binding interactions that presumably occur simultaneously between different Kaps, transport factors and FG Nups.44 Assuming sub-μM binding affinities were required to ensure Kap selectivity, the NPC would clog and remain spatially inaccessible under such crowding conditions. How then does specific binding lead to fast Kap translocation? More so, how does a collective FG Nup barrier fit and function in such a crowded space? How does space aid or attenuate transport?

The first clue to shed light on the problem was uncovered in 2006 when Yang and Musser found that the transport efficiency and interaction time of specific cargoes were inversely impacted by Kapβ1 concentration.36 Using permeabilized cells, they found that low Kap concentrations (i.e., < 1 μM Kapβ1) yielded long interaction times (i.e., slow) and low transport efficiency whereas high Kapβ1 concentrations (i.e., 15 μM Kapβ1) yielded short interaction times (i.e., fast) and high transport efficiency. This was later corroborated by Timney et al who showed that increasing amounts of Kaps in vivo did indeed expedite rather than slow down cargo import rates.45 Now, to argue from a FG-centric point-of-view, transport selectivity and speed should follow from specific Kap-FG Nup binding as a criterion to alleviate barrier (spatial) constraints in the pore. But presuming the NPC is mostly occluded by FG Nups (arranged such as in a highly cross-linked meshwork), Kap binding and occupancy in the pore would more likely obstruct space and hinder traffic at cellular Kap concentrations. Likewise, low Kap concentrations would lead to faster translocation due to low Kap occupancy and more free space in the pore. Given that the converse is true, one has to ponder how a spacious pore delays transport, while a more crowded one expedites it. Do the FG Nups retain the same barrier conformation, identity and role in spite of these differences? As noted by Yang and Musser,36 changes in pore occupancy could provide “a general means by which cargo interaction times and transport efficiencies can be modulated.”

A second subsequent clue lay in the observation that Kap-FG binding caused a collapse of FG Nup brushes, particularly at the low Kap concentrations tested, because this showed that FG Nup conformations changed with Kap binding.21 A third ensued from results showing that the presence of Kaps helped to tighten the barrier against non-specific entities in artificial NPCs46 and FG Nup gels.47 Fourth, even non-specific molecules could modulate and weaken Kap-FG Nup binding.29 Together these intersecting lines of evidence reveal the inherent sensitivity of the FG Nups to microenvironmental factors that can impact on NPC selectivity and transport kinetics.

Biophysical Evidence of Kap-centric Control

To investigate the molecular basis of these effects, we found it important to reproduce some basic features of the NPC microenvironment at the biophysical level,14 such as (i) constraining the FG Nups to a surface via a covalent tether, (ii) reproducing FG-repeat density within such a FG layer, and (iii) studying the behavior of FG layers under physiological Kap concentrations. This “peeling open” of the pore was achieved using a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technique that we developed to correlate in situ equilibrium and kinetic aspects of Kapβ1-FG Nup binding to changes in FG layer conformation and Kapβ1 occupancy.48 Briefly, this used BSA molecules as innate molecular probes that could “feel” the physical barrier properties of a surface-tethered molecular layer49 by not binding the FG Nups.

A common outcome we found was an increase in layer height with decreasing next-neighbor grafting distance (increased lateral crowding).26 This indicated molecular brush formation, which underscores the role of surface tethering as a major determinant of FG Nup morphology. We stress that this does not preclude intra-/inter-FG Nup cohesion, but merely explains that the FG Nups are extended and oriented in a net perpendicular direction under such surface constraints. At low Kapβ1 concentrations, we found that Kapβ1 molecules exhibited slow kinetic off rates due to strong Kap-FG Nup binding (KD ⪅ 1 μM) that correlated with FG layer collapse.21 Stepwise increases in Kapβ1 concentrations then led to a gradual re-extension of the FG layer.26,44,48 This so-called “self-healing” can be attributed to an increase in population (and volume) of bound Kapβ1 within the FG layers, as predicted by Zilman theory.50,51 It should be noted that this was true for Nup153, Nup214, and Nup62 and its yeast ortholog Nsp1, with the exception of Nup98,26 which exhibited pronounced cohesion based on its poor extensibility and low capacity for incorporating Kapβ1.

Going further, we observed a “pile-up” of Kapβ1 due to limited penetration into preoccupied FG layers at physiological Kapβ1 concentrations (∼10 µM), which correlated with weak binding (KD ⪆ 10 μM) and fast kinetic off rates.26,44,48 This indicates that the occupancy of bound Kapβ1 modulates subsequent kinetic behavior in a differential manner, being attributed to how many available FG-repeats each incoming Kapβ1 molecule can access and bind to. Hence, fast transport emerges from a reduction of avidity due to a saturation of the FG Nup layer with pre-bound Kapβ1. Interestingly, this impacts on other transport factors, such as, the Ran importer nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2), which also exhibited weakened binding and fast off-rates in the presence of bound Kapβ1.44 Thus, Kapβ1 preloading may also reinforce the NPC permeability barrier against more hydrophobic, non-specific cargoes.

To further validate these effects, we studied the diffusive motion of Kapβ1-functionalized colloidal particles (i.e. Kap-probes) on FG layers in the presence of soluble Kapβ1.52 There, we found that the Kap-probes remained stuck to the FG layer (i.e., slow) at low Kapβ1 concentrations but exhibited unhindered 2-dimensional diffusion on the layer (i.e., fast) at physiological Kapβ1 concentrations. In contrast, non-specific control probes exhibited 3-dimensional diffusion that only transiently impinged the FG layer but did not bind. Evidently, the increase in Kapβ1 occupancy could diminish multivalent interactions between the Kap-probe and the FG layer until binding was sufficiently balanced to maintain selectivity, but weak enough to facilitate 2-dimensional diffusion. By analogy, this is reminiscent of a “dirty velcro effect” where Kap-probe adhesion to the FG layer is reduced as more soluble Kapβ1 molcules occupy it. It is further noteworthy that this provided the physical proof-of-principle that corroborates the “reduction of dimensionality” (ROD) hypothesis of Adam and Delbruck,53 later adapted by Peters for the NPC.54 Basically, ROD explains that the selectivity and efficiency of biomolecular transport must involve facilitated diffusional processes that are confined to one- or 2-dimensions. [Note: For an in-depth explanation of ROD, see Berg and von Hippel.55] Based on this evidence, we concluded that FG Nup conformation, Kap occupancy and transport kinetics are closely interrelated.

Cellular Evidence of Kap-centric Control

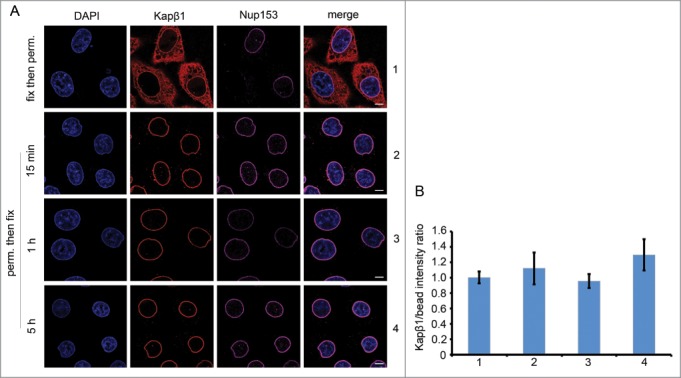

Populating the NPC with strongly bound Kaps may serve to reinforce barrier functionality while providing for a finely tuned microenvironment that facilitates transport selectivity and speed. Indeed, immunostaining HeLa cells that were first fixed and then digitonin-permeabilized reveals the unperturbed steady-state cellular localization of endogenous Kapβ1. As before,56 this yields a distinct nuclear rim staining as shown in Figure 1. To further test for retention strength, we find that a similar staining of endogenous Kapβ1 persists in cells that were first permeabilized then incubated in buffer for prolonged periods of up to 5 hours prior to fixation. Here, the lack of any quantifiable attenuation in the fluorescence signal after prolonged exposure to such severe dilution conditions indicates that the NPC-bound fraction of Kapβ1 is extremely stable and long-lived. This is consistent with the findings of Lowe et al who showed that exogenous Kapβ1 exhibits at least two kinetically distinct pools in digitonin-permeabilized cells, one being stably bound to the NPC for tens of minutes, and another that is expedited in the presence of RanGTP.40 Similar bimodal kinetics has also been reported for GFP-Kapβ142 in permeabilized cells and mRNA export in living cells.57 Interestingly, it was found that additions of exogenous Kapβ1,40 as well as other receptors58 further reduced NPC permeability against passive cargoes, thereby recapitulating the role of Kaps as bona fide constituents of the NPC. Moreover, Yang and Musser,36 as well as Timney et al45 showed in vitro and in vivo respectively, that increasing amounts of Kaps expedited cargo import rates, rather than slowing it down. Taken together, this evidence indicates that a pool of strongly bound Kaps that occupy the NPC at physiological concentrations facilitates the speed and selectivity of transport. As a consequence, we reason that a lack of Kap retention rather than a lack of FG repeats59 leads to appreciable leakiness.

Figure 1.

The NPC-bound fraction of endogenous Kapβ1 is stable and long-lived. (A) Row 1: HeLa cells were fixed and digitonin-permeabilized as described in ref. 56. As a control, anti-Kapβ1 (Abcam) staining reveals the steady state distribution of endogenous Kapβ1, a fraction of which is localized at the nuclear envelope. This further co-localizes with anti-Nup153 (Sigma) staining, thereby signifying the presence of Kapβ1 at the NPCs. Row 2 to 4: To test for the retention of the NPC-bound pool of endogenous Kapβ1, cells were first digitonin-permeabilized then incubated in PBS buffer for 15 mins, 1 hr and 5 hr respectively, followed by fixation. The persistence of anti-Kapβ1 staining at the nuclear envelope up to 5h incubation indicates that the NPC-bound fraction of Kapβ1 is very stable and long-lived. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) The immunofluorescent staining of Kapβ1 localized at the nuclear envelope was calibrated against InSpeck™ Red calibration beads (Life Technologies) to exclude intensity variations between measurements. The data shown corresponds to Rows 1 to 4 in (A). Final intensity ratios are normalized to the control sample (Row 1) to facilitate comparisons between experiments. Student's t-test analysis (p>0.05) shows a neglectable difference among these experimental outcomes. All images were obtained using a point scanning laser confocal microscope (LSM700, Zeiss AG).

Implications of Kap-centric Control

But how can selective transport proceed more rapidly than passive diffusion?8 A parsimonious interpretation of Kap-centric control suggests that Kaps are weakly bound and more labile in regions of low FG-repeat availability. This may be a narrow corridor along the NPC central axis that is demarcated by strongly bound Kaps that occupy high FG-repeat density regions surrounding the pore wall. Indeed, such a picture is consistent with the preferred localization of Kapβ1 in the NPC as observed in single molecule fluorescence experiments,60,61 as well as structural changes inside the central channel as revealed by cryo-electron tomography.62 Fast transport kinetics would then emerge from a culmination of 3 effects along this corridor: (i) reduced Kap-FG repeat binding, (ii) ROD, and (iii) spatial confinement.

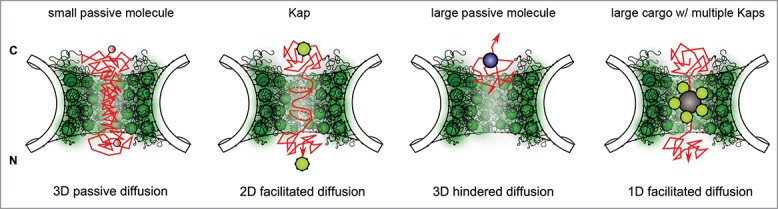

To illustrate this, we consider the 4 different transport scenarios shown in Figure 2. First, small molecules that traverse the NPC corridor by passive diffusion do so in a 3-dimensional random walk, leading to comparably long “search” trajectories and passage times before exiting the NPC. Notably, collisions with other diffusing entities in the NPC corridor (omitted for clarity of illustration) such as dynamically fluctuating FG Nups, Kaps, as well as both specific and non-specific cargoes are likely to further delay passage. In comparison, weakly bound Kaps might exhibit a 2-dimensional random walk along the luminal “surface” of the translocation corridor owing to the dirty velcro effect with brief excursions into the luminal space.52 This could in fact expedite transport because the temporal requirement of a 2-dimensional search process for finding the exit of a spatially constrained pore can be considerably less than in 3 dimensions. According to ROD theory,53,55 the mean diffusion time τ for a particle (assuming a constant diffusion coefficient) is related to

| (1) |

| (2) |

where b is the radius of a small target (e.g., pore exit) and L is the radius of a larger diffusional space (e.g., pore). Likewise, NTF244 as well as non-specific molecules that exert sufficient FG-repeat binding63,64 might exhibit varying degrees of ROD-like translocation.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical translocation scenarios in the NPC. Left to right: Small passive molecules that diffuse into the NPC exhibit long 3D search trajectories (and therefore long dwell times) due to a lack of FG-Nup binding. The dirty velcro effect reduces the travel distance of Kaps by promoting 2D diffusion along the luminal surface of the translocation corridor. This reduction of dimensionality leads to shorter dwell times and rapid translocation rates. Large non-specific molecules experience hindered diffusion and have a lower probability to enter the pore. Increased pore confinement and the dirty velcro effect expedite the translocation of large cargoes with multiple Kaps due to reduced search trajectories that stem from 1D diffusion. Note: For clarity of illustration, other diffusing entities have been omitted from each drawing. However, overlaying these scenarios does reveal how different spatiotemporal routes might co-exist in the pore. C = cytoplasm, N = nucleus.

In the absence of FG-repeat binding, large non-specific molecules would have a lower probability to enter the pore due to hindered diffusion near the Kap-centric barrier. Yet, this raises fundamental questions as to how very large receptor-cargo complexes traverse the NPC corridor upon entering the pore. More specifically, how can sufficient space be created to accommodate large cargoes in the NPC? One possible explanation could be that the NPC structurally dilates with increasing Kap occupancy.65 Regardless, it is important to bear in mind that the barrier is not a solid obstruction but rather consists of dynamic interactions between diffusing Kaps and fluctuating FG Nups. Being highly flexible, Kapβ1 may even adopt slightly different conformations depending on the NPC microenvironment.66 Nevertheless, from the perspective of Kap-centric control a displacement of preloaded Kaps from the FG Nups would result in the effective retraction/reduction of the NPC barrier. We speculate that the presence of multiple Kaps on large cargoes67,68 (or receptors that shuttle messenger ribonucleic proteins57,69) may be able to displace preloaded Kaps because of increased binding avidity with the FG Nups. Indeed, the presence of multiple Kaps has also shown to improve the transport efficiency of large cargoes.68 Finally, the increased confinement within the pore may promote relatively fast transport via quasi one-dimensional diffusion.67 All in all these scenarios are consistent with the notion that passage through the NPC is not a rate-limiting step57 – except when long-lived Kaps are depleted from the pore.

Conclusion

Kap-centric control describes a view where NPC transport selectivity and speed are regulated by the occupancy of Kaps in the pore. This departs from FG-centric views in that the FG Nups might function as malleable molecular “receptacles” that accumulate Kaps at NPCs. This alludes to how Kaps regulate and reinforce the FG Nups in a concentration dependent manner to bring about NPC barrier function. Importantly, Kap-centric control provides the missing link in FG-centric views by reconciling mechanistic and kinetic requirements of the NPC. Not only does this impact on the binding and transport kinetics of subsequent Kaps, but also the diffusion volume inside the NPC, which together determine transport rates. Moreover, multivalent interactions with the FG Nups confer onto Kaps the ability to establish a continuum of different kinetic behaviors. Therefore, under certain cellular cues different Kaps may access different temporal pathways rather than only spatial ones.70 For instance, the activation of signaling pathways38 can cause a regulation or deregulation of certain Kaps (leading to perturbations in their expression levels i.e., concentrations) with physiological or pathological consequences such as cancer.71,72 Thus, Kap-centric control may serve to regulate nucleocytoplasmic transport by fine-tuning the NPC microenvironment according to the functional needs of the cell.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We thank K D Schleicher for valuable discussions.

Funding

This work is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant 31003A_146614 [RYHL].

References

- 1.Wente SR, Rout MP. The Nuclear Pore Complex and Nuclear Transport. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010; 2:a000562; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a000562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck M, Forster F, Ecke M, Plitzko JM, Melchior F, Gerisch G, Baumeister W, Medalia O. Nuclear pore complex structure and dynamics revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science 2004; 306:1387-90; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1104808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keminer O, Peters R. Permeability of single nuclear pores. Biophys J 1999; 77:217-28; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76883-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorlich D, Vogel F, Mills AD, Hartmann E, Laskey RA. Distinct functions for the 2 importin subunits in nuclear-protein import. Nature 1995; 377:246-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/377246a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulikas T. Putative nuclear-localization signals (NLS) in protein transcription factors. J Cell Biochem 1994; 55:32-58; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcb.240550106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chook YM, Sueel KE. Nuclear import by karyopherin-betas: Recognition and inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1813:1593-606; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cingolani G, Petosa C, Weis K, Muller CW. Structure of importin-β bound to tbe IBB domain of importin-α. Nature 1999; 399:221-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/20367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran EJ, King MC, Corbett AH. Macromolecular transport between the nucleus and the cytoplasm: Advances in mechanism and emerging links to disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1843:2784-95; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning DP, Patel SS, Uversky V, Fink AL, Rexach M. Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: The FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:2450-5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0437902100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayliss R, Littlewood T, Stewart M. Structural basis for the interaction between FxFG nucleoporin repeats and importin-β in nuclear trafficking. Cell 2000; 102:99-108; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bednenko J, Cingolani G, Gerace L. Importin β contains a COOH-terminal nucleoporin binding region important for nuclear transport. J Cell Biol 2003; 162:391-401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200303085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isgro TA, Schulten K. Binding dynamics of isolated nucleoporin repeat regions to importin-β. Structure 2005; 13:1869-79; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronshaw JA, Krutchinsky AN, Zhang WZ, Chait BT, Matunis MJ. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 2002; 158:915-27; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200206106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peleg O, Lim RYH. Converging on the function of intrinsically disordered nucleoporins in the nuclear pore complex. Biol Chem 2010; 391:719-30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/bc.2010.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahrenkrog B, Maco B, Fager AM, Koser J, Sauder U, Ullman KS, Aebi U. Domain-specific antibodies reveal multiple-site topology of Nup153 within the nuclear pore complex. J Struct Biol 2002; 140:254-67; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1047-8477(02)00524-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkinson CE, Mattheyses AL, Kampmann M, Simon SM. Conserved spatial organization of FG domains in the nuclear pore complex. Biophys J 2013; 104:37-50; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardarelli F, Lanzano L, Gratton E. Capturing directed molecular motion in the nuclear pore complex of live cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:9863-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1200486109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bestembayeva A, Kramer A, Labokha AA, Osmanovic D, Liashkovich I, Orlova EV, Ford IJ, Charras G, Fassati A, Hoogenboom BW. Nanoscale stiffness topography reveals structure and mechanics of the transport barrier in intact nuclear pore complexes. Nat Nanotechnol 2015; 10:60-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nnano.2014.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frey S, Gorlich D. A saturated FG-repeat hydrogel can reproduce the permeability properties of nuclear pore complexes. Cell 2007; 130:512-23; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huelsmann BB, Labokha AA, Goerlich D. The permeability of reconstituted nuclear pores provides direct evidence for the selective phase model. Cell 2012; 150:738-51; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim RYH, Fahrenkrog B, Koser J, Schwarz-Herion K, Deng J, Aebi U. Nanomechanical basis of selective gating by the nuclear pore complex. Science 2007; 318:640-3; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1145980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim RYH, Huang NP, Koser J, Deng J, Lau KHA, Schwarz-Herion K, Fahrenkrog B, Aebi U. Flexible phenylalanine-glycine nucleoporins as entropic barriers to nucleocytoplasmic transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:9512-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0603521103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada J, Phillips JL, Patel S, Goldfien G, Calestagne-Morelli A, Huang H, Reza R, Acheson J, Krishnan VV, Newsam S, et al.. A bimodal distribution of two distinct categories of intrinsically disordered structures with separate functions in FG nucleoporins. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010; 9:2205-24; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.M000035-MCP201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuxreiter M, Toth-Petroczy A, Kraut DA, Matouschek AT, Lim RYH, Xue B, Kurgan L, Uversky VN. Disordered proteinaceous machines. Chem Rev 2014; 114:6806-43; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/cr4007329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terry LJ, Wente SR. Flexible gates: Dynamic topologies and functions for FG nucleoporins in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Eukaryot Cell 2009; 8:1814-27; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/EC.00225-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapinos LE, Schoch RL, Wagner RS, Schleicher KD, Lim RYH. Karyopherin-centric control of nuclear pores based on molecular occupancy and kinetic analysis of multivalent binding with FG nucleoporins. Biophys J 2014; 106:1751-62; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milles S, Lemke EA. Mapping multivalency and differential affinities within large intrinsically disordered protein complexes with segmental motion analysis. Angew Chem Int Ed 2014; 53:7364-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/anie.201403694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Polyvalent interactions in biological systems: Implications for design and use of multivalent ligands and inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed 1998; 37:2755-94; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20%3c2754::AID-ANIE2754%3e3.0.CO;2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tetenbaum-Novatt J, Hough LE, Mironska R, McKenney AS, Rout MP. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: a role for non-specific competition in karyopherin-nucleoporin interactions. Mol Cell Proteomics 2012; 11:31-46; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.M111.013656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pyhtila B, Rexach M. A gradient of affinity for the karyopherin Kap95p along the yeast nuclear pore complex. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:42699-709; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M307135200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben-Efraim I, Gerace L. Gradient of increasing affinity of importin β for nucleoporins along the pathway of nuclear import. J Cell Biol 2001; 152:411-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.152.2.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lott K, Bhardwaj A, Mitrousis G, Pante N, Cingolani G. The importin β binding domain modulates the avidity of importin β for the nuclear pore complex. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:13769-80; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.095760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dange T, Grunwald D, Grunwald A, Peters R, Kubitscheck U. Autonomy and robustness of translocation through the nuclear pore complex: A single-molecule study. J Cell Biol 2008; 183:77-86; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200806173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubitscheck U, Grunwald D, Hoekstra A, Rohleder D, Kues T, Siebrasse JP, Peters R. Nuclear transport of single molecules: dwell times at the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 2005; 168:233-43; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200411005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siebrasse JP, Peters R. Rapid translocation of NTF2 through the nuclear pore of isolated nuclei and nuclear envelopes. EMBO Rep 2002; 3:887-92; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang WD, Musser SM. Nuclear import time and transport efficiency depend on importin β concentration. J Cell Biol 2006; 174:951-61; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200605053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowalczyk SW, Kapinos L, Blosser TR, Magalhaes T, van Nies P, Lim RYH, Dekker C. Single-molecule transport across an individual biomimetic nuclear pore complex. Nat Nanotechnol 2011; 6:433-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nnano.2011.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu L, Massague A. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of signal transducers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004; 5:209-19; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohler A, Hurt E. Exporting RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007; 8:761-73; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe AR, Tang JH, Yassif J, Graf M, Huang WYC, Groves JT, Weis K, Liphardt JT. Importin-β modulates the permeability of the nuclear pore complex in a Ran-dependent manner. eLife 2015; 4:e04052; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7554/eLife.04052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paradise A, Levin MK, Korza G, Carson JH. Significant proportions of nuclear transport proteins with reduced intracellular mobilities resolved by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J Mol Biol 2007; 365:50-65; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tokunaga M, Imamoto N, Sakata-Sogawa K. Highly inclined thin illumination enables clear single-molecule imaging in cells. Nat Methods 2008; 5:159-61; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosammaparast N, Pemberton LF. Karyopherins: from nuclear-transport mediators to nuclear-function regulators. Trends Cell Biol 2004; 14:547-56; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner RS, Kapinos LE, Marshal NJ, Stewart M, Lim RYH. Promiscuous binding of karyopherin β 1 modulates FG nucleoporin barrier function and expedites NTF2 transport kinetics. Biophys J 2015; 108:918-27; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timney BL, Tetenbaum-Novatt J, Agate DS, Williams R, Zhang WZ, Chait BT, Rout MP. Simple kinetic relationships and nonspecific competition govern nuclear import rates in vivo. J Cell Biol 2006; 175:579-93; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200608141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jovanovic-Talisman T, Tetenbaum-Novatt J, McKenney AS, Zilman A, Peters R, Rout MP, Chait BT. Artificial nanopores that mimic the transport selectivity of the nuclear pore complex. Nature 2009; 457:1023-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frey S, Gorlich D. FG/FxFG as well as GLFG repeats form a selective permeability barrier with self-healing properties. EMBO J 2009; 28:2554-67; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoch RL, Kapinos LE, Lim RYH. Nuclear transport receptor binding avidity triggers a self-healing collapse transition in FG-nucleoporin molecular brushes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:16911-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1208440109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoch RL, Lim RYH. Non-interacting molecules as innate structural probes in surface plasmon resonance. Langmuir 2013; 29:4068-76; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/la3049289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Opferman MG, Coalson RD, Jasnow D, Zilman A. Morphological control of grafted polymer films via attraction to small nanoparticle inclusions. Phys Rev E 2012; 86:031806; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.031806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Opferman MG, Coalson RD, Jasnow D, Zilman A. Morphology of polymer brushes infiltrated by attractive nanoinclusions of various sizes. Langmuir 2013; 29:8584-91; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/la4013922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schleicher KD, Dettmer SL, Kapinos LE, Pagliara S, Keyser UF, Jeney S, Lim RYH. Selective transport control on molecular velcro made from intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Nanotechnol 2014; 9:525-30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nnano.2014.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adam G, Delbrueck M. Reduction of dimensionality in biological diffusive processes In: Rich A, Davidson N, eds. Struct Chem and Mol Biol. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co., 1968:198-215 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peters R. Translocation through the nuclear pore complex: Selectivity and speed by reduction-of-dimensionality. Traffic 2005; 6:421-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berg OG, Vonhippel PH. Diffusion-controlled macromolecular interactions Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem 1985; 14:131-60; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.bb.14.060185.001023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chi NC, Adam EJH, Adam SA. Sequence and characterization of cytoplasmic nuclear-protein import factor p97 J Cell Biol 1995; 130:265-74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.130.2.265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gruenwald D, Singer RH. In vivo imaging of labelled endogenous b-actin mRNA during nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 2010; 467:604-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature09438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohr D, Frey S, Fischer T, Guttler T, Gorlich D. Characterisation of the passive permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J 2009; 28:2541-53; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strawn LA, Shen TX, Shulga N, Goldfarb DS, Wente SR. Minimal nuclear pore complexes define FG repeat domains essential for transport. Nat Cell Biol 2004; 6:197-206; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma J, Goryaynov A, Sarma A, Yang W. Self-regulated viscous channel in the nuclear pore complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:7326-31; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1201724109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma J, Yang W. Three-dimensional distribution of transient interactions in the nuclear pore complex obtained from single-molecule snapshots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:7305-10; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0908269107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eibauer M, Pellanda M, Turgay Y, Dubrovsky A, Wild A, Medalia O. Structure and gating of the nuclear pore complex. Nat Comm 2015; 6:7532; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms8532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naim B, Zbaida D, Dagan S, Kapon R, Reich Z. Cargo surface hydrophobicity is sufficient to overcome the nuclear pore complex selectivity barrier. EMBO J 2009; 28:2697-705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshimura SH, Kumeta M, Takeyasu K. Structural mechanism of nuclear transport mediated by importin β and flexible amphiphilic proteins. Structure 2014; 22:1699-710; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.str.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koh J, Blobel G. Allosteric Regulation in Gating the Central Channel of the Nuclear Pore Complex. Cell 2015; 161:1361-73; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halder K, Dolker N, Van Q, Gregor I, Dickmanns A, Baade I, Kehlenbach RH, Ficner R, Enderlein J, Grubmuller H, et al.. MD Simulations and FRET Reveal an Environment-Sensitive Conformational Plasticity of Importin-β. Biophys J 2015; 109:277-86; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lowe AR, Siegel JJ, Kalab P, Siu M, Weis K, Liphardt JT. Selectivity mechanism of the nuclear pore complex characterized by single cargo tracking. Nature 2010; 467:600-3; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature09285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tu LC, Fu G, Zilman A, Musser SM. Large cargo transport by nuclear pores: implications for the spatial organization of FG-nucleoporins. EMBO J 2013; 32:3220-30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2013.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mor A, Suliman S, Ben-Yishay R, Yunger S, Brody Y, Shav-Tal Y. Dynamics of single mRNP nucleocytoplasmic transport and export through the nuclear pore in living cells. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:543-U61; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Terry LJ, Wente SR. Nuclear mRNA export requires specific FG nucleoporins for translocation through the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 2007; 178:1121-32; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200704174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kau TR, Way JC, Silver PA. Nuclear transport and cancer: From mechanism to intervention. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4:106-17; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kimura M, Imamoto N. Biological significance of the importin-β family-dependent nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways. Traffic 2014; 15:727-48; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/tra.12174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]