Abstract

Exposure to cobalt in the hard metal industry entails severe adverse health effects, including lung cancer and hard metal fibrosis. The main aim of this study was to determine exposure air concentration levels of cobalt and tungsten for risk assessment and dose–response analysis in our medical investigations in a Swedish hard metal plant. We also present mass-based, particle surface area, and particle number air concentrations from stationary sampling and investigate the possibility of using these data as proxies for exposure measures in our study. Personal exposure full-shift measurements were performed for inhalable and total dust, cobalt, and tungsten, including personal real-time continuous monitoring of dust. Stationary measurements of inhalable and total dust, PM2.5, and PM10 was also performed and cobalt and tungsten levels were determined, as were air concentration of particle number and particle surface area of fine particles. The personal exposure levels of inhalable dust were consistently low (AM 0.15mg m−3, range <0.023–3.0mg m−3) and below the present Swedish occupational exposure limit (OEL) of 10mg m−3. The cobalt levels were low as well (AM 0.0030mg m−3, range 0.000028–0.056mg m−3) and only 6% of the samples exceeded the Swedish OEL of 0.02mg m−3. For continuous personal monitoring of dust exposure, the peaks ranged from 0.001 to 83mg m−3 by work task. Stationary measurements showed lower average levels both for inhalable and total dust and cobalt. The particle number concentration of fine particles (AM 3000 p·cm−3) showed the highest levels at the departments of powder production, pressing and storage, and for the particle surface area concentrations (AM 7.6 µm2·cm−3) similar results were found. Correlating cobalt mass-based exposure measurements to cobalt stationary mass-based, particle area, and particle number concentrations by rank and department showed significant correlations for all measures except for particle number. Linear regression analysis of the same data showed statistically significant regression coefficients only for the mass-based aerosol measures. Similar results were seen for rank correlation in the stationary rig, and linear regression analysis implied significant correlation for mass-based and particle surface area measures. The mass-based air concentration levels of cobalt and tungsten in the hard metal plant in our study were low compared to Swedish OELs. Particle number and particle surface area concentrations were in the same order of magnitude as for other industrial settings. Regression analysis implied the use of stationary determined mass-based and particle surface area aerosol concentration as proxies for various exposure measures in our study.

KEYWORDS: cobalt exposure in the hard metal industry, occupational exposure, particle mass, particle number, particle surface area, personal exposure measurements, stationary measurements

INTRODUCTION

Occupational exposure to cobalt in the hard metal industry is mainly associated with powder and tool production and the use of hard metal tools for manufacturing of industrial products.

Hard metal (cemented carbide) is an alloy based on tungsten carbide and cobalt acting as a binder matrix, consisting of 70–95% tungsten and 5–30% cobalt. Other components could be TiC (titanium carbide), TiN (titanium nitride), Ti(C)N (titanium carbide-nitride), and TaC (tantalum carbide). Almost 15% of the worldwide production of cobalt is used for hard metal production and Sweden is one of the major producers.

Occupational exposure during production of hard metal is associated with several adverse health effects implicating cobalt as the causing agent. Those effects include rhinitis, sinusitis, bronchitis (Balmes, 1987; Cugell et al., 1990), asthma (Shirakawa et al., 1989; Kusaka et al., 1989; Nemery et al., 1990), dose-related decreased lung function over time (Kusaka et al., 1986a; Rehfisch et al., 2012), and hard metal lung disease (HMLD) (Nemery et al., 1990; Ruokonen et al., 1996; Nureki et al., 2013; Nakamura et al., 2014). Allergic dermatitis (Kusaka et al., 1989; Nakamura et al., 2014), caused both by direct contact and by skin exposure from deposited air particles (Gimenez Camarasa, 1967; Dooms-Goossens et al., 1986) is reported. Cobalt exposure is also known to cause cardiomyopathy (Barborik and Dusek, 1972; Kennedy et al., 1981) and in a cohort study of hard metal workers an increased incidence of ischemic heart disease was noted (Hogstedt and Alexandersson, 1990). An increased risk to develop lung cancer is also seen among people working in the hard metal production industry (Lasfargues et al., 1994; Moulin et al., 1998; Wild et al., 2000; Lombaert et al., 2013) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified cobalt metal with tungsten as probably carcinogenic to humans (group 2A) (IARC, 2006). Emerging evidence suggests the primary route for uptake of cobalt is through inhalation, however dermal uptake have also been shown (Scansetti et al., 1994).

Occupational exposure measurement in the hard metal industry have showed air concentrations of total dust ranging from 128 to 4031 μg m−3, with the highest levels in scrap reclamation and powder handling departments and the lowest in dry grinding departments (Stefaniak et al., 2007; Stefaniak et al., 2009). The cobalt air concentrations varied between 1 and 6.4×103 μg m−3 (Kusaka et al., 1986b; Kumagai et al., 1996) and the highest levels were found in the powder handling areas, the pressing department and in the sintering workshop (Kusaka et al., 1986b; Kumagai et al., 1996; Kraus et al., 2001; Stefaniak et al., 2009). The corresponding data for tungsten exposures ranged from 3 to 417 μg m−3, the highest levels were measured in the powder processing areas and in the heavy alloy production areas (Kraus et al., 2001; Stefaniak et al., 2009). In addition to mass-based particle air concentrations, a special interest in particle number, and particle surface area concentrations due to suggested pulmonary and cardiovascular effects (Oberdörster et al., 1996; Peters et al., 2001).

We have performed a large project representing the Swedish hard metal industry on airborne and dermal exposure to cobalt and tungsten, effects on the respiratory system as well as on inflammatory and coagulatory markers addressing association with cardiovascular diseases. In this article, personal exposure and stationary sampling of cobalt and tungsten reflecting different particle size mass-based air concentrations will be presented for risk assessment, as well as particle number and particle surface area air concentrations. We will also investigate the possibility of using comprehensive stationary measurements as proxies for exposure measures for further use in the dose–response analysis in our main project.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study object

The hard metal production company in our study is one of the world leading companies producing hard metal cutting tools with affiliations in Sweden and 60 other countries. Approximately one million carbide inserts are produced per week and about 1200 workers are employed. The production of hard metal tools consists of several steps, the first being the formation of tungsten carbide (WC) from tungsten oxide and elementary carbon through carburization to form WC powder. Secondly, mixing of tungsten carbide and cobalt powders is performed, followed by granulation. After granulation the material is pressed, pre-sintered (heated) and then accurately machined into desired shapes. The pieces are finally sintered at 1400–1500°C to reach the hardness near diamond. The products are then sand blasted and covered with a protective layer and as a last step the finished products are quality inspected, stored, and shipped out of the plant.

Study design and sampling strategy

As part of the main study between November 2007 and June 2009, the following departments were selected for personal exposure and area measurements: powder production, pressing, maintenance (pressing), charging/decharging, PVD and CVD furnaces, periphery grinding (shape and grade), process laboratory, warehouse, and inspection. Informed oral and written consent was obtained from each participant and 72 employees agreed to participate in our study. In addition to personal exposure measurements, stationary measurements by department of mass-based, particle surface area, and particle number concentrations were performed.

A total of 72 personal exposure measurements for inhalable and total dust were carried out. Cobalt and tungsten were analyzed in both dust fractions. Cobalt in the total dust fraction is important since the transition from sampling cobalt in the total dust fraction quite recently was changed to the inhalable fraction. Standardized exposure measurements are necessary for our dose response analysis. For 52 of the participants, real-time full shift monitoring was also performed using a personal data logger (DataRAM) and they were asked to keep a log showing time and duration of their work tasks. Measurements were conducted during an 8-h work shift and almost all measurements of total and inhalable dust exceeded 85% of full shift sampling time (8h).

In total, 28 stationary measurements were carried out. Stationary measurements of total and inhalable dust, PM2.5 (particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter <2.5 µm), and PM10 (particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm) were performed simultaneously as the personal measurements and strategically placed at the same departments. Cobalt and tungsten were determined in the different dust fractions. Two separate sets of equipment were used for stationary sampling of inhalable and total dust for validation of concentration profiles and the mean of the parallel measurements are presented and used for calculations. Real-time measurements were conducted as 27 measurements for particle number and 22 particle surface area air concentrations. Sampling time for all stationary measurements was 8h.

Sampling, measurements, and analysis

Personal exposure measurements

Sampling of total dust was performed according to a modified version of National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health Manual of Analytical Methods 0500 (NIOSH, 1994) using an open faced cassette (OFC) with a 25-mm cellulose acetate filter (Millipore 3 μm pore size) and an airflow of 2.0 l min−1. Inhalable dust was collected using a GSP filter head (GSA Messgerätebau GmbH, Gut Vellbrüggen, Germany) with a 37-mm cellulose acetate filter (Sartorius Stedim 8 μm pore size) connected to a pump (GSA SG4000, Messgerätebau GmbH, Gut Vellbrüggen, Germany) operated at an air flow of 3.5 l min−1 (HSE, 2000). The filter cassettes were placed in the breathing zone for the personal exposure measurement. Determination of deposited amount of dust on the filters was made gravimetrically. A standard analytical procedure of metal analysis on each filter was performed with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HP 4500 ICP-MS, Agilent Technologies Inc.) (ICP-MS) for cobalt and tungsten (NIOSH, 2003). Real-time monitoring of dust concentrations was performed with and aerosol monitor (DataRAM model pDR 1000ANm MIE Inc., Bedford, MA, USA), measuring particles with a diameter between 0.1 to 10 µm in the range 0.001–400mg m−3 with optimal sensitivity for the respirable fraction of dust (<5 µm). The instrument was placed in the breathing zone and registrations of dust concentrations were every 10s.

Stationary area measurements

Stationary measurements of total and inhalable dust were performed in accordance to the standardized sampling methods used for the personal exposure measurements outlined above.

Chempass TM Pumping System was used for PM2.5 and PM10 personal samplers (Ruprecht and Patashnik, NY, USA) with a 37-mm cellulose acetate filter (Millipore 0.8 μm pore size) and an air flow rate of 1.8 l min−1 (EN 12341, 1999; EN 14907, 2005; EPA, 2006). The deposited amount of dust on the filters was gravimetrically determined.

A diffusion particle sensor, A-trak, was used to measure the particle surface area (µm2·cm−3) in the size range 10–1000nm. The A-trak (model 9000, TSI GmbH, Aachen, Germany) is based on diffusion charging of sampled particles, followed by detection of the charged particles using an electrometer. Registration was performed every second and the instrument was calibrated in the respirable fraction, range 1–10 000 µm2·cm−3.

The particle number concentration (p·cm−3) was measured with a P-trak (model 8525, TSI GmbH, Aachen, Germany) in the size range 0.02 to 1 μm. The P-trak is based on the condensation particle counting technique using isopropyl alcohol and data was registered every 2s.

All analyses were performed at the laboratory at the Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Örebro University Hospital, Örebro, Sweden. The laboratory is accredited for sampling and analyses of both dust and metals by the Swedish Board of Accreditation and Conformity Assessment (SWEDAC).

Occupational exposure limits

The occupational exposure limits (OELs) used in this study are defined as the time weighted average (TWA) concentrations for an 8-h work day. Personal exposure air concentration data in our study were compared with the current Swedish OELs set by the Swedish Work Environment Authority (SWEA) and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) threshold limit values (TLVs). The Swedish OELs are set to10mg m−3 for inhalable dust, 0.02mg m−3 for cobalt in the inhalable dust fraction, and 5mg m−3 for tungsten in the total dust fraction (SWEA, 2011) and ACGIH are presenting TLVs of 0.02mg m−3 for inorganic cobalt compounds and 5mg m−3 for tungsten. TLVs for particles (insoluble or poorly soluble) not otherwise specified (PNOS) are set to be kept below 3mg m−3 for respirable dust and 10mg m−3 for inhalable dust (ACGIH, 2015).

Statistical methods

The total and inhalable dust concentrations and the corresponding cobalt and tungsten concentrations of the personal measurements were determined and presented for various department titles. The exposure was calculated as an 8-h time-weighted average concentration (8-h TWA) for the full-work day.

For descriptive purposes, standard parameters [arithmetic mean (AM), standard deviation (SD), geometric mean (GM), geometric standard deviation (GSD), and range] were calculated for the log normal distribution of all the measurements, including the stationary sample of the aerosol mass fractions, the concentrations of particle number, and particle surface area. For the direct reading instruments DataRAM, P-trak, and A-trak, the median air concentration was calculated for each 8-h sampling period and presented mass based as mg m−3, the number of particles as p·cm−3, and particle surface area as µm2·cm−3 used for further comparisons and data calculations.

The limit of detection (LOD) is defined as 3 SD for a concentration with signal-to-noise ratio of 3. The detection limits are <40 μg for dust, <0.01 μg, and <0.2 μg for cobalt and tungsten respectively (JCGM, 2008). The corresponding air concentrations are <0.04mg m−3 for dust, <0.00001mg m−3 for cobalt, and <0.0002mg m−3 for tungsten for an 8-h full work shift sample and a flow rate of 2 l min−1. Measurements below LOD were assigned LOD/√2 before the final calculations (Hornung and Reed, 1990).

To investigate the possibility of using the mass-based exposure measurements as proxies for other exposure measures, to be used in the main project including medical examinations, correlation analysis was performed. Rank correlation (Spearman’s rank correlation) based on personal and stationary area measurements comparison, including inhalable and total dust, particle number, and particle surface area concentrations, was also performed. Regression analysis was used to analyze relations between exposure measurements and stationary measurements. Linear models and logarithmic model (ln) values were presented and both the dependent and independent variables were ln-transformed. For the regression coefficient presented, percentage changes in the independent variable are directly related to percentage changes in the dependent. Based on relevant air concentration levels, individual dependent variables (different exposure metrics) were predicted, including confidence limits. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.0.

RESULTS

Personal exposure measurements

The inhalable personal dust air concentration ranged from <0.023 to 3.0mg m−3 (AM 0.15mg m−3) and all were below the current Swedish OEL (10mg m−3) see Table 1. The highest level (3.0mg m−3) was determined for work at the PVD furnace. Cobalt and tungsten in the inhalable fraction ranged between 0.000028–0.056mg m−3 (AM 0.0030mg m−3) and 0.00027–0.570mg m−3 (AM 0.022mg m−3), respectively. The highest levels of both cobalt and tungsten were measured in the powder production department. For cobalt, 6% of the samples (n = 72) exceeded the Swedish OEL (0.02mg m−3). These samples represented spray drying at the powder production department, set work in the laboratory and operating the PVD furnace. The GSD’s for cobalt and tungsten in the inhalable fraction were wide (>3) at the departments of powder production, PVD furnace and process laboratory and for inhalable dust at the PVD furnace. Some of the workers at the powder production performed office work and packaging outside the powder department, implying very low exposures and creating wide GSD’s. At the PVD furnaces, one of the cobalt air concentrations were very high compared to the others, mainly caused by furnace maintenance and blasting. At the process laboratory, one of the laboratory technicians were working with powder testing causing cobalt levels even above the new Swedish OEL, generating wide GSD’s.

Table 1.

Personal air concentration exposure to the inhalable fraction of dust, cobalt, and tungsten by department (mg m−3) (n = 72)

| Department | n | AM | SD | GM | GSD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powder production | Dust | 9 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 2.3 | 0.062–0.91 |

| Co | 9 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.0043 | 4.5 | 0.00051–0.056 | |

| W | 9 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.050 | 3.8 | 0.0046–0.57 | |

| Pressing | Dust | 27 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.072 | 2.1 | <0.023–1.1 |

| Co | 27 | 0.0014 | 0.00096 | 0.0012 | 1.8 | 0.00043–0.0043 | |

| W | 27 | 0.011 | 0.0073 | 0.0090 | 1.7 | 0.0037–0.036 | |

| Maintenance (pressing) | Dust | 1 | 0.056 | ||||

| Co | 1 | 0.00085 | |||||

| W | 1 | 0.0061 | |||||

| Periphery grinding (shape) | Dust | 11 | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.051 | 1.4 | 0.026–0.087 |

| Co | 11 | 0.00017 | 0.00012 | 0.00014 | 1.8 | 0.000065–0.00048 | |

| W | 11 | 0.0019 | 0.0011 | 0.0017 | 1.6 | 0.0010–0.0046 | |

| Periphery grinding (grade) | Dust | 1 | 0.048 | ||||

| Co | 1 | 0.00056 | |||||

| W | 1 | 0.0061 | |||||

| Charging/decharging | Dust | 6 | 0.053 | 0.019 | 0.050 | 1.4 | 0.030–0.084 |

| Co | 6 | 0.00013 | 0.000072 | 0.00012 | 1.7 | 0.000056–0.00025 | |

| W | 6 | 0.00099 | 0.00034 | 0.00094 | 1.4 | 0.00066–0.0015 | |

| PVD furnace | Dust | 3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.32 | 6.9 | 0.092–3.0 |

| Co | 3 | 0.0087 | 0.013 | 0.0032 | 5.7 | 0.0010–0.024 | |

| W | 3 | 0.039 | 0.055 | 0.017 | 4.8 | 0.0055–0.10 | |

| CVD furnace | Dust | 2 | 0.056 | 0.034 | 0.050 | 1.9 | 0.032–0.080 |

| Co | 2 | 0.00025 | 0.00022 | 0.00019 | 2.9 | 0.000088–0.00040 | |

| W | 2 | 0.0016 | 0.0012 | 0.0013 | 2.3 | 0.00075–0.0024 | |

| Process laboratory | Dust | 6 | 0.12 | 0.022 | 0.12 | 1.2 | 0.095–0.15 |

| Co | 6 | 0.0070 | 0.013 | 0.0020 | 5.2 | 0.00032–0.034 | |

| W | 6 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.0093 | 3.4 | 0.0017–0.035 | |

| Warehouse | Dust | 2 | 0.11 | 0.0094 | 0.11 | 1.1 | 0.10–0.11 |

| Co | 2 | 0.00018 | 0.000074 | 0.00017 | 1.5 | 0.00013–0.00023 | |

| W | 2 | 0.0015 | 0.00054 | 0.0014 | 1.5 | 0.0011–0.0019 | |

| Inspection | Dust | 4 | 0.070 | 0.022 | 0.068 | 1.4 | 0.046–0.094 |

| Co | 4 | 0.000066 | 0.000031 | 0.000060 | 1.7 | 0.000028–0.000093 | |

| W | 4 | 0.00055 | 0.00027 | 0.00050 | 1.7 | 0.00027–0.00090 | |

| Total | Dust | 72 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.079 | 2.2 | <0.023–3.0 |

| Co | 72 | 0.0030 | 0.0083 | 0.00068 | 5.0 | 0.000028–0.056 | |

| W | 72 | 0.022 | 0.071 | 0.0056 | 4.5 | 0.00027–0.57 |

AM, arithmetic mean; GM, geometric mean; GSD, geometric standard deviation; n, number of measurements; SD, standard deviation; range, min–max.

The total dust air concentrations varied between <0.040–1.8mg m−3 (AM 0.13mg m−3) and the highest level was found for work at the PVD furnace (data not shown in table). The levels of cobalt and tungsten in the total dust fractions were <0.000011–0.028 (AM 0.0018mg m−3) and 0.00028–0.28mg m−3 (AM 0.014mg m−3), respectively. The highest levels of cobalt were determined in the powder production work area. All tungsten samples were below the Swedish OEL (5mg m−3).

Measurements conducted using data RAM showed peak values between 0.001 and 83mg m−3 for certain work tasks, the average of all 8-h shifts (AM 0.058mg m−3) (data not shown).

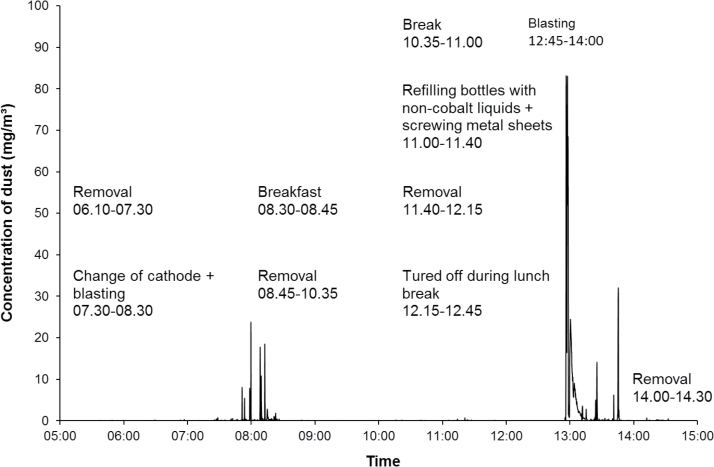

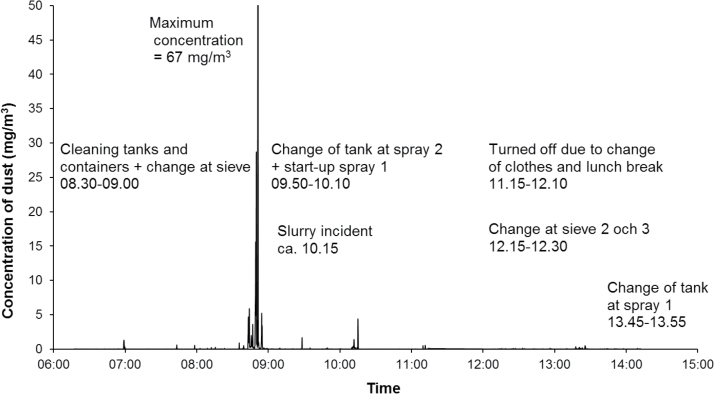

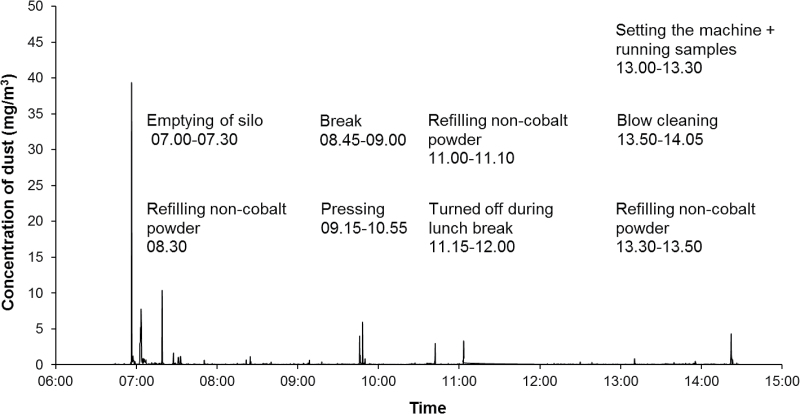

The highest peak exposure (83mg m−3) was measured during blasting of hard metal pieces at the PVD-furnace department. The same person performed a change of cathode and blasted another time, but those work tasks resulted in lower peaks (Fig. 1). High peak exposures were also recorded for spray drying during cleaning of tanks and vessels (67mg m−3) at the powder production department (Fig. 2). Work at the pressing department showed high exposures for emptying of a silo (39mg m−3) and some lower peaks for pressing work (Fig. 3). Other work tasks with high peak exposures were set work with refilling of powder at the pressing department (3 and 4.3mg m−3), packing bags with powder (19mg m−3) at the powder production department, packing at the warehouse department (5.4mg m−3), and maintenance work at the charging/decharging department. In Supplementary Appendix 1, available at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online, additional time exposure profiles with exposure peaks >3mg m−3 are presented including specifications of work tasks.

Figure 1.

Measurements with DataRAM at the PVD furnace.

Figure 2.

Measurements with DataRAM at the powder department (spray drying).

Figure 3.

Measurements with DataRAM at the pressing department.

For the personal sampling of the inhalable dust, 2 out of 72 of the measurements were <LOD at the pressing department. For the personal inhalable cobalt concentration, all measurements were above the LOD.

Stationary area measurements-rig sampling

The overall average (AM) for the 8-h TWA stationary data regarding inhalable and total dust were 0.03 and 0.044mg m−3, respectively. Average stationary inhalable dust levels were lower than the corresponding average for the exposure measurements, 0.15mg m−3. The corresponding average for inhalable and total cobalt air concentrations were 0.00074 and 0.00071mg m−3, respectively (Table 2). For PM10 and PM2.5, the average air concentration levels were 0.052 and 0.049mg m−3, respectively. Regarding cobalt PM10 cobalt (AM 0.00043) levels were higher than PM2.5 cobalt (AM 0.000031), indicating a cobalt particle size distribution with coarse rather than fine particles. The relation between cobalt in PM10 and PM2.5 (1:10) indicates airway rather than alveolar deposition. However, it should be noted that this is data for agglomerated particles. The range of GSD’s varied between 1.4 and 5.4, with the widest GSD’s for cobalt in the inhalable, total dust, and PM10 fraction. These wide GSD′s reflect exposure contrast between powder and packaging, and the very low LOD for cobalt in air, when compared with the determined cobalt air concentration (a ratio of 1:100) are responsible for our findings (Table 2). In Supplementary Appendix 2, available at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online, stationary area sampling results by department is presented.

Table 2.

Stationary air concentration levels of total dust, inhalable dust, PM2.5, PM10, cobalt, and tungsten (mg m−3) and real-time measurements of particle surface area and particle number concentrations (n = 28)

| Substance | n | AM | SD | GM | GSD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhalable dust | 28 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.027 | 1.6 | <0.01–0.07 |

| Co (inhal) | 27a | 0.00074 | 0.00092 | 0.0003 | 5.0 | <0.0000041–0.0034 |

| W (inhal) | 27a | 0.0056 | 0.0058 | 0.0027 | 4.0 | <0.000081–0.017 |

| Total dust | 28 | 0.044 | 0.025 | 0.04 | 1.4 | <0.03–0.15 |

| Co (tot) | 28 | 0.00071 | 0.0011 | 0.00024 | 5.3 | <0.0000071–0.0053 |

| W (tot) | 28 | 0.0051 | 0.0058 | 0.0024 | 3.9 | <0.00014–0.02 |

| PM2.5 | 28 | 0.049 | 0.029 | 0.044 | 1.6 | <0.042–0.14 |

| Co (PM2.5) | 28 | 0.000031 | 0.000037 | 0.000018 | 2.7 | <0.000010–0.00016 |

| W (PM2.5) | 28 | 0.00039 | 0.00043 | 0.00028 | 2.1 | <0.00021–0.0021 |

| PM10 | 28 | 0.052 | 0.025 | 0.048 | 1.6 | <0.042–0.12 |

| Co (PM10) | 28 | 0.00043 | 0.00048 | 0.00018 | 5.0 | <0.000010–0.0017 |

| W (PM10) | 28 | 0.0032 | 0.0033 | 0.0017 | 3.6 | <0.00023–0.011 |

| Particle surface area (µm2·cm−3) mean | 22 | 7.6 | 3.9 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 2.1–15 |

| Particle surface area (µm2·cm−3) min | 22 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1 | 2.3 | 1–6.9 |

| Particle surface area (µm2·cm−3) max | 22 | 150 | 560 | 30 | 3.6 | 5.9–2700 |

| Particle number (p·cm−3) mean | 27 | 3000 | 1500 | 2700 | 1.6 | 1200–8000 |

| Particle number (p·cm−3) min | 27 | 1200 | 620 | 1000 | 1.8 | 220–2900 |

| Particle number (p·cm−3) max | 27 | 13 000 | 13 000 | 9400 | 2.3 | 2500–54 000 |

AM, arithmetic mean; n, number of measurements; GSD, geometric standard deviation; GM, geometric mean; SD, standard deviation; range: min–max.

aOne filter was missing.

As for fine particles, the average particle number concentration was 3×103 p·cm−3, ranging from 1.2×103 to 8.0×103 p·cm−3. The individual samples varied between 220 and 54×103 p·cm−3 (Table 2). The highest levels were recorded at the powder production department at the weigh station (40×103 p·cm−3) and at the powder press (26×103 p·cm−3), at the coating department (54×103 p·cm−3) and at the storage (46×103 p·cm−3).

The overall average particle surface area air concentration was 7.6 μm2·cm−3, ranging from 2.1 to 15 μm2·cm−3. The individual samples ranged from 1 to 2700 μm2·cm−3. The highest levels were determined at the weigh station at the powder production department (201 μm2·cm−3) and at the pressing department (2700 μm2·cm−3). However, the average particle number or particle surface area concentration did not differ between departments. The amount of measurements <LOD are 46% for inhalable dust and 59% for total dust, but for cobalt and tungsten in the inhalable fraction only 4% were <LOD and in the total fraction the corresponding amount was 5%for cobalt and 4% for tungsten. For PM2.5, the amount <LOD is 61%, PM2.5 Co 54% and PM2.5W 57% and PM10 50% and PM10 Co and W 11%. However, in all our regression and prediction analyses we are only using cobalt air concentration data, our stationary data for inhalable and total dust when presented as means and standard deviation should be interpreted with caution.

Correlation ranking

The exposure measurements of inhalable cobalt were correlated with the corresponding stationary area inhalable cobalt air concentrations, initially by ranking (Table 3). The rank correlations coefficients (Spearman’s rho) varied between −0.461 to 0.868 for personal inhalable and total cobalt when compared to rig data, all statistically significant for the mass-based measures and for particle surface area. Inverse correlations was seen for the pressing and charging/decharging departments. No correlation was determined for particle number air concentrations.

Table 3.

Rank correlations coefficients (Spearman’s rho) between personal exposure and stationary area measurementsa

| Aerosol fraction Personal measurements | Stationary area measurements | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhalable dust Co (mg m3) | Total dust Co (mg m3) | PM2.5 Co (mg m3) | PM10 Co (mg m3) | Particle surface area Median (μm2·m3) | Particle number Median (p·cm3) | |

| Inhalable dust Co (mg m−3) | 0.832b | 0.868b | 0.630b | 0.771b | −0.461c | −0.057 |

| Total dust Co (mg m−3) | 0.781b | 0.867b | 0.710b | 0.788b | −0.460c | −0.047 |

a n = 28, except for particle surface area (n = 22) and particle number (n = 27).

bSignificant correlation at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

cSignificant correlation at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

The stationary measurement data showed a similar pattern, the rank correlation coefficients varied between −0.617 to 0.945 for the mass-based measures and particle surface area air concentrations, all statistically significant. No significant correlation was determined for particle number air concentration (Table 4). The highest correlation coefficient was noted for total cobalt versus PM10 cobalt (rho = 0.945). Inverse correlations were found between particle surface area and most of the mass-based aerosol measures, Spearman’s rho ranging from −0.278 to −0.617. The departments with inverse correlations were pressing, charging/decharging and the process lab. Correlations were also determined when particle surface area and particle number was compared (rho = 0.630).

Table 4.

Rank correlations coefficients (Spearman’s rho) between different particle measures in the stationary area measurementsa

| Aerosol fraction | Inhalable dust Co (mg m−3) | PM2.5 Co (mg m−3) | PM10 Co (mg m−3) | Particle surface area Median (μm2·m−3) | Particle number Median (p·cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dust Co (mg m−3) | 0.893b | 0.598b | 0.945b | −0.583b | −0.159 |

| Inhalable dust Co (mg m−3) | 0.527b | 0.864b | −0.617b | −0.145 | |

| PM2.5 Co (mg m−3) | 0.681b | −0.278 | 0.257 | ||

| PM10 Co (mg m−3) | −0.557b | −0.097 | |||

| Particle surface area Median (μm2·m−3) | 0.630b |

a n = 28, except for particle particle surface (n = 22) and particle number (n = 27).

bSignificant correlation at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Regression and prediction

Linear regression analysis of exposure and stationary area rig measurement data was performed trying to estimate other mass-based fractions and particle number and particle surface area air concentrations based on exposure data (Table 5).

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis of different particle measures based on stationary area measurements as dependent and personal inhalable cobalt exposure as independent variablesa,b

| Aerosol fraction (Dependent; Independent) | Regression | Prediction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (p) | 95% CI (β) | r 2 | Predicted concentrationc | 95% CI (y)d | |

|

Inhalable Co (S);

Inhalable Co (P) |

0.884 (<0.001) |

0.626–1.14 | 0.675 | 0.00530 | 0.000611–0.0460 |

|

Particle surface area (S);

Inhalable Co (P); |

−0.153 (0.127) |

−0.353 to 0.048 | 0.118 | 3.49 | 1.00–12.3 |

|

Particle number (S);

Inhalable Co (P) |

0.015 (0.799) |

−0.104 to 0.134 | 0.003 | 2540 | 944–6900 |

P, personal exposure measurements; β, regression coefficient; 95% CI (β), 95% confidence interval for β; r 2, correlation coefficient; S, stationary measurements.

aAll data ln-transformed, except predicted concentrations presented in original units.

b n = 28, except for particle surface area (n = 22) and particle number (n = 27).

cPredicted concentration = predicted individual concentration for inhalable cobalt 0.02mg m−3.

dCI (y) = 95% confidence interval for predicted dependent metrics, individual concentrations.

Significant regression coefficients for inhalable cobalt (P < 0.001) was determined and a predicted air concentration of 0.00530mg m−3 in comparison with the 0.02mg m−3 assigned was seen. The confidence intervals were very wide. No correlation was seen for inhalable cobalt and particle surface area and particle number.

Linear regression analysis based on stationary area measurements, i.e. inhalable cobalt stationary area measurements used to estimate other particle measures, showed statistically significant regression coefficients (P < 0.05) for estimating cobalt levels of total dust, PM2.5, PM10, and even particle surface area from inhalable dust in our stationary area measurements (Table 6). No correlation was determined for particle number air concentrations. Strong explained variance for inhalable cobalt versus PM10 (r 2 = 0.680) was seen. The predicted values for inhalable cobalt levels of 0.02mg m−3 using our regression model showed a predicted concentration level, 0.00557mg m−3. However, the predictions of different exposure metrics for inhalable cobalt concentrations showed very wide confidence intervals. The linear regression analysis for the stationary measurements also showed an almost unity relation between cobalt in the inhalable fraction compared to cobalt in the total dust fraction (β = 0.95, P < 0.001, CI = 0.77–1.1 (ln values, not shown in table).

Table 6.

Linear regression analysis of stationary area measurements with inhalable cobalt as the independent variable and other particle fractions as dependenta,b

| Aerosol fraction (Dependent; Independent) | Regression | Prediction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (p) | 95% CI (β) | r 2 | Predicted concentrationc | 95% CI (y)d | |

|

PM2.5Co (S);

Inhalable Co (S) |

0.345(0.002) | 0.139–0.552 | 0.332 | 0.0000726 | 0.0000112–0.0000495 |

|

PM10Co (S);

Inhalable Co (S) |

0.831(<0.001) | 0.591–1.07 | 0.680 | 0.00557 | 0.000599–0.0518 |

|

Particle surface area (mean) (S);

Inhalable Co (S) |

−0.201(0.037) | −0.387 to (−0.014) | 0.221 | 2.89 | 0.770–10.8 |

|

Particle number (mean) (S);

Inhalable Co (S) |

−0.040(0.509) | −0.164 to 0.084 | 0.019 | 2276 | 742–6970 |

β, regression coefficient; r 2, correlation coefficient; S, stationary area measurements; 95% CI (β), 95% confidence interval for β.

aAll data ln-transformed, except predicted concentrations presented in original units.

b n = 28, except for particle surface area (n = 22) and particle number (n = 27).

cPredicted concentration = predicted individual concentration for inhalable cobalt 0.02mg m−3.

dCI (y) = 95% confidence interval for predicted dependent metrics, individual concentrations.

DISCUSSION

The exposures to cobalt and tungsten in a Swedish hard metal plant were investigated for all departments and jobs potentially exposed to cobalt, providing representative data for a state of the art modern production facility. In general, the exposures were below the Swedish OEL for inhalable cobalt (0.02mg m−3), however with some samples (6 %) exceeding the OEL. The high concentrations were determined for powder production, laboratory and furnace work. High peak exposures of dust, ranging up to 83mg m−3, was also determined.

Ongoing discussions of adverse health effects and the importance of determining other than mass-based particle measures, made us include particle number and particle surface area concentrations in our measurements. Good rank correlation (Spearman’s rho) for mass-based and particle surface area air concentrations were determined when exposure and stationary data was compared. When linear regression was applied for these data, significant correlations were determined only for the mass-based inhalable and total cobalt, including predicted air concentrations levels using our regression model with very large confidence intervals, i.e. introducing high uncertainties for individual predictions.

All the departments and potentially exposed groups were included for the standard personal exposure, the stationary area sampling and the real-time aerosol measurements. However, nickel was not present and according to our information not used in the Swedish hard metal plants. In our historical measurement database, nickel was determined but found to be at very low levels and still the exposure issue for the hard metal industry would be cobalt or tungsten when discussing various adverse health effects.

For the personal sampling of the inhalable dust, 2 out of 72 of the measurements were <LOD, but for the personal inhalable and total dust cobalt concentration all measurements were above the LOD. For the stationary sampling data, used in our regressions analysis, the corresponding data were 4% below the LOD for both fractions. For cobalt and tungsten in inhalable and total dust, our fractions of interest, almost all concentrations were above LOD.

For the particle fractions evaluated by gravimetry, these figures were much higher and they should be used with caution.

An extensive Japanese study (Kumagai et al., 1996) with exposure focus including 970 measurements, all full shift samples, reported cobalt exposures of ambient personal monitoring of 0.007–6.4mg m−3 for powder production, 0.006–0.248mg m−3 for pressing (machine), for shaping 0.001–1.1mg m−3 and for grinding 0.001 to 0.482mg m−3. Those levels are in accordance with cobalt exposure in Germany (Kraus et al., 2001) with levels in powder production varying between 0.008 and 0.064mg m−3, pressing 0.0009–0.12mg m−3 and grinding 0.002–0.081mg m−3. The German study also included exposure measurements of tungsten, ranging from 0.003 to 0.417mg m−3 (our data ranging from 0.00027 to 0.057mg m−3). A US study presented cobalt data from personal exposure measurement using 37mm closed face filter cassettes, i.e. total dust, for different departments. For powder production, the GMs ranged from 0.026 to 0.126mg m−3, forming, machining and grinding from 0.002 to 0.030mg m−3 (Stefaniak et al., 2007). A Finnish study presented data on manufacturing of hard metal products, the overall range of 8-h TWAs were 0.002 to 0.240mg m−3, for the corresponding grinding of stellite work blades for sharpening the TWAs ranged from 0.002 to 0.032mg m−3 (Linnainmaa et al., 1996).

For our cobalt data, the overall mean for inhalable cobalt was 0.003mg m−3, ranging from 0.00003 to 0.056mg m−3. In relation to other survey data, our cobalt levels seem very low, most likely reflecting state of the art production technique and subsequently effects of proper elimination measures driven by decreased OELs and awareness of adverse health effects of cobalt. No data on exposure or stationary sampling of particle number or particle surface area concentrations have been presented for the hard metal industry, however stationary air measurement data from a survey representing a blend of Swedish industries showed particle number concentration ranging from 12 000 to 22 000 p·cm−3 and particle surface area concentrations ranging from 45 to 3800 μm2·cm−3 (Westberg et al., 2015) (in preparation). Our air concentration levels for both particle number and particle surface are much lower, well reflecting the difference in average total dust concentration, 0.033mg m−3 for our hard metal industry compared to 1.1mg m−3 of total dust for the Swedish study.

The advantages of real-time measurements by using portable aerosol monitors are obvious when looking for short-term exposures and exposure measures linked to acute adverse health effects, i.e. respiratory symptoms or irritations (Woskie et al., 1993; Wegman et al., 1994; Edman et al., 2003). Our DataRAM data represents full shift real-time dust concentrations for 52 workers, with potential use as an exposure measure in our main study when correlating exposure and acute respiratory effects. Indeed, very high peak concentrations in spite of low daily average levels have been determined. To illustrate, blasting hard metal pieces gave very high concentrations up to 83mg m−3. Other tasks with high peak aerosol concentrations were set work and refilling of powder, washing of tanks and containers, removal and replenishment of crucibles, and manual cleaning. Surprisingly, work at the warehouse packing cobalt powder also showed a peak exposure for one person (5mg m−3). Continuous monitoring with DataRAM will help target the high peak exposures over time and identify critical work tasks that needs to be addressed in order to reduce exposure levels. That could be accomplished by changing work routines or technical modifications in the facility. A work task could be performed differently even though carried out by the same person, resulting in a variety of exposure peaks, not necessarily related to work. This type of data is necessary for successful prevention and we have provided jobs with peak values >3mg m−3 in Supplementary Appendix 1, available at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online.

Attempts to validate and interpret the instrumental response in terms of respirable and inhalable dust have been thoroughly investigated (Thorpe and Walsh, 2007). For an aerosol with a mass median aerodynamic diameter of about 7 µm, the mass-based DataRAM response was twice the respirable fraction. The conversion factors between the instrument and respirable, total, and inhalable dust heavily depend on the particle size distribution of the aerosol. In spite of these uncertainties, the instrument could always be used to describe peak exposures in comparative measurements.

We used both inhalable and total dust parallel personal and stationary sampling due to internationally different sampling techniques related to the exposure limits. In the United States, the 8-h TWA TLV for cobalt is 0.02mg m−3, at present defined as total dust although the ACGIH (ACGIH, 2015) intention is to replace total dust with more size selective. Total dust sampling normally means sampling using a 25 or 37mm filter cassette with open or closed face. However, in Sweden (SWEA, 2011) the OEL is defined as inhalable dust fraction, with the same numerical value, 0.02mg m−3.

The relations between inhalable and total aerosol are of a more common interest, especially since many international agencies, such as American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) and Swedish Work Environment Authority (SWEA) intend to or recently have replaced the OELs based on sampling of total dust samples with samples of inhalable dust. Moreover, studies published before the alteration of OEL are presenting measured concentrations in the total dust fraction and dose–response relationships in comparison to total dust levels. In order to use data for dose–response analyses from this study in our main project regarding effects on the respiratory system and inflammatory and coagulatory markers indicating association with cardiovascular diseases, we have decided to present levels of total dust as well as inhalable dust. It should be emphasized that all correlations between personal and area sampling are specific for each study, but our results suggests if any quantitative relationship is possible to establish in our study. The relations between inhalable and total dust fractions for various environments are highly depending on the particle size distributions of the aerosols. A potential problem is that varying relation between the fractions might demand different OELs or a conversion factor when the sampled matrix is changed from total dust to inhalable dust.

In our data, the regression analysis of cobalt in the inhalable dust fraction and the total dust fraction at our different static sampling sites at different departments showed on overall almost unity relation (β = 0.95) and a inhalable dust concentration of 0.02mg m−3 showed predicted total dust cobalt concentration of 0.013mg m−3. Differences between inhalable and total dust fractions occur when there are large amounts of coarse particles (> 18 um), if not, the relation should be unity. Resolving the regression analysis into different departments, only the powder production area showed deviations when inhalable and total dust cobalt comparison were noted.

However, when the different exposure fractions were compared with rank correlation, particle surface area and particle number were all inversely correlated to the mass-based particle measures, in particular for the pressing, charging–decharging departments and the process lab representing low cobalt concentrations.

For these findings, we suggest an ongoing agglomeration process in the stationary sampling sites, where agglomeration based on the same mass levels results in decreased surface area and particle number compared to personal sampling, in particular with increasing concentration levels.

We have investigated the possibility of using stationary measurements as proxies for personal exposure measurements for different particle air concentration fractions in a hard metal plant. The correlation between personal and area sampling have been reviewed, both theoretically (Esmen and Hall, 2000) and in practical evaluations of available data from different studies. Historically, Sherwood and Greenhalgh (1960) found differences in exposure assessment values when old stationary instruments were replaced by more modern personal pumps, Cherrie (2003) published an evaluation of 12 studies with personal and static samplers, the median ratio personal to static workplace air concentrations were 1.5, 80 % of the data were >1. Earlier summarization of published studies showed ratios varying from 1.2 to 8.5 (Cherrie, 1999). The general explanation for differences in the ratio between the personal and static sampling lies in the location of the static sampler versus the source of the main emission causing exposure, i.e. the near field and the far field and the ventilation rate in the different areas. Poor ventilation implies low ratios and good ventilation high ratios when personal and stationary area measurements are compared. Based on our data, good ranking correlation was achieved when personal exposure of inhalable and total cobalt air concentrations were compared to the corresponding stationary sampling. Of more interest are the relations we have established between personal and static sampling based on linear regression analysis. Our findings and conditions at our hard metal plant are in line with the literature reviews, we consider our ventilation in the different department very good and our stationary sampling sites were located in a far field, implying considerably higher concentration for the exposure measurements.

How can we explain our findings, reflecting good possibilities for using stationary sampling mass-based data as a proxy for exposure measures but less clear relations for particle surface area and particle number? In a general concepts for spherical particles, the mass is proportional to the product of particle density and the cube of the diameter (ρ p d 3) and the surface area is proportional to the square of the diameter (d 2), whereas the number of particles is independent of the particle diameter, and hence is proportional to the diameter raised to the power of zero (d 0). However, when the numbers of ultrafine particles are high, a significant correlation could be expected (Heitbrink et al., 2009) between the number of particles and surface area as experienced in our study (rho = 0.630) in the rig sampling.

DECLARATION

The study is financed by a Swedish hard metal company. The basic contract set up was stating Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (DOEM) as responsible for study design, planning and operative sampling in the workplace. All the analyses of air samples, dermal, and biological samples were performed by the DOEM. The company was responsible for providing workers and proper areas for the medical investigations at different sites in the plant for sampling and medical investigations. DOEM was responsible for producing Swedish confidential reports appropriate for covering the questions raised in the contracted research. Regarding international publication, DOEM was also responsible for the scientific contents of the work, writing, editing and any approving of the manuscript before submitting to a scientific journal. The company had no influence on the conclusion of the manuscript. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Regional Ethical Review board in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr 2007/260).

CONCLUSIONS

In general, the exposures were below the Swedish OEL for inhalable cobalt (0.02mg m−3) and tungsten, however with some cobalt samples (6%) exceeding the OEL. The high concentrations were determined for powder production, laboratory, and furnace work. High peak exposures of dust, ranging up to 83mg m−3 was also determined, demanding surveillance programme and preventive measures with focus on short-term exposures. Using specific particle mass-based exposure measurement data as proxies for other particle mass-based, particle number, and particle surface area concentrations by ranking was successful for all measures but for particle number. For linear regression analysis, only the mass-based measures were correlated, suggesting caution when mass-based exposure measurement data should be used as proxies for particle surface area or particle number air concentrations.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data can be found at http://annhyg.oxfordjournals.org/.

REFERENCES

- ACGIH (2015) Threshold llimit valuse for chemical substances and physical agents and biological exposure indices. Cincinnati: American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. [Google Scholar]

- Balmes JR. (1987) Respiratory effects of hard-metal dust exposure. Occup Med; 2: 327–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barborik M, Dusek J. (1972) Cardiomyopathy accompaning industrial cobalt exposure. Br Heart J; 34: 113–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrie JW. (1999) The effect of room size and general ventilation on the relationship between near and far-field concentrations. Appl Occup Environ Hyg; 14: 539–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrie JW. (2003) The beginning of the science underpinning occupational hygiene. Ann Occup Hyg; 47: 179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cugell DW, Morgan WK, Perkins DG, et al. (1990) The respiratory effects of cobalt. Arch Intern Med; 150: 177–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooms-Goossens AE, Debusschere KM, Gevers DM, et al. (1986) Contact dermatitis caused by airborne agents. A review and case reports. J Am Acad Dermatol; 15: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman K, Lofstedt H, Berg P, et al. (2003) Exposure assessment to alpha- and beta-pinene, delta(3)-carene and wood dust in industrial production of wood pellets. Ann Occup Hyg; 47: 219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EN 12341 (1999) Air quality. Determination of the PM10 fraction of suspended particulate matter. Reference method and field test procedure to demonstrate reference equivalence of measurement methods. Brussels: European Comittee for Standardization. [Google Scholar]

- EN 14907 (2005) Ambient air quality. Standard gravimetric measurement method for the determination of the PM2,5 mass fraction of suspended particulate matter. Brussels: Eueopean Comittee for Standardization. [Google Scholar]

- EPA (2006) Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Available at http://epa.gov/fedrgstr/EPA-AIR/2006/January/Day-17/a179.pdf Accessed January17 2006.

- Esmen NA, Hall TA. (2000) Theoretical investigation of the interrelationships between stationary and personal sampling in exposure estimation. Appl Occup Environ Hyg; 15: 114–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez Camarasa JM. (1967) Cobalt contact dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol; 47: 287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitbrink WA, Evans DE, Ku BK, et al. (2009) Relationships among particle number, surface area, and respirable mass concentrations in automotive engine manufacturing. J Occup Environ Hyg; 6: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogstedt C, Alexandersson R. (1990) Dödsorsaker hos hårdmetallarbetare. Solna, Sweden: National Institute of Occupational Health; (In Swedish). [Google Scholar]

- Hornung R, Reed L. (1990) Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. App Occup Environ Hyg; 5: 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- HSE (2000) MDHDS: General methods for sampling and gravimetric analysis of inhalable and respirable dust. Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Suffolk, UK. [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2006) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Cobalt in Hard Metals and Cobalt Sulfate, Gallium Arsenide, Indium Phosphide and Vanadium Pentoxide. Lyon, France: IARC Press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JCGM (2008) Evaluation of measurement data: guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement 100:2008. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM). [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A, Dornan JD, King R. (1981) Fatal myocardial disease associated with industrial exposure to cobalt. Lancet; 1: 412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus T, Schramel P, Schaller KH, et al. (2001) Exposure assessment in the hard metal manufacturing industry with special regard to tungsten and its compounds. Occup Environ Med; 58: 631–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai S, Kusaka Y, Goto S. (1996) Cobalt exposure level and variability in the hard metal industry of Japan. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J; 57: 365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaka Y, Ichikawa Y, Shirakawa T, et al. (1986. a) Effect of hard metal dust on ventilatory function. Br J Ind Med; 43: 486–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaka Y, Yokoyama K, Sera Y, et al. (1986. b) Respiratory diseases in hard metal workers: an occupational hygiene study in a factory. Br J Ind Med; 43: 474–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaka Y, Nakano Y, Shirakawa T, et al. (1989) Lymphocyte transformation with cobalt in hard metal asthma. Ind Health; 27: 155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasfargues G, Wild P, Moulin JJ, et al. (1994) Lung cancer mortality in a French cohort of hard-metal workers. Am J Ind Med; 26: 585–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnainmaa M, Kangas J, Kalliokoski P. (1996) Exposure to airborne metals in the manufacture and maintenance of hard metal and stellite blades. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J; 57: 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombaert N, Castrucci E, Decordier I, et al. (2013) Hard-metal (WC-Co) particles trigger a signaling cascade involving p38 MAPK, HIF-1alpha, HMOX1, and p53 activation in human PBMC. Arch Toxicol; 87: 259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin JJ, Wild P, Romazini S, et al. (1998) Lung cancer risk in hard-metal workers. Am J Epidemiol; 148: 241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Nishizaka Y, Ariyasu R, et al. (2014) Hard metal lung disease diagnosed on a transbronchial lung biopsy following recurrent contact dermatitis. Intern Med; 53: 139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemery B, Nagels J, Verbeken E, et al. (1990) Rapidly fatal progression of cobalt lung in a diamond polisher. Am Rev Respir Dis; 141: 1373–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH (1994) Method 0500: Particulates not otherwise regulated, total. In NIOSH Manual of analytical methods. Cincinnati: National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH (2003) Method 7300: elements by ICP. In NIOSH Manual of analytical methods. 4 ed. Cincinnati: National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) [Google Scholar]

- Nureki S, Miyazaki E, Nishio S, et al. (2013) Hard metal lung disease successfully treated with inhaled corticosteroids. Intern Med; 52: 1957–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdörster G, Finkelstein J, Ferin J, et al. (1996) Ultrafine particles as a potential environmental health hazard. Studies with model particles. Chest; 109: 68s–9s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Frohlich M, Doring A, et al. (2001) Particulate air pollution is associated with an acute phase response in men; results from the MONICA-Augsburg Study. Eur Heart J; 22: 1198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfisch P, Anderson M, Berg P, et al. (2012) Lung function and respiratory symptoms in hard metal workers exposed to cobalt. J Occup Environ Med; 54: 409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruokonen EL, Linnainmaa M, Seuri M, et al. (1996) A fatal case of hard-metal disease. Scand J Work Environ Health; 22: 62–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scansetti G, Botta GC, Spinelli P, et al. (1994) Absorption and excretion of cobalt in the hard metal industry. Sci Total Environ; 150: 141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood RJ, Greenhalgh DM. (1960) A personal air sampler. Ann Occup Hyg; 2: 127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa T, Kusaka Y, Fujimura N, et al. (1989) Occupational asthma from cobalt sensitivity in workers exposed to hard metal dust. Chest; 95: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, Day GA, Harvey CJ, et al. (2007) Characteristics of dusts encountered during the production of cemented tungsten carbides. Ind Health; 45: 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, Virji MA, Day GA. (2009) Characterization of exposures among cemented tungsten carbide workers. Part I: Size-fractionated exposures to airborne cobalt and tungsten particles. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol; 19: 475–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWEA (2011) Occupational Exposure Limit Values (AFS 2011:18). Solna, Sweden: Swedish Work Environment Authority; (In Swedish). [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe A, Walsh PT. (2007) Comparison of portable, real-time dust monitors sampling actively, with size-selective adaptors, and passively. Ann Occup Hyg; 51: 679–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegman DH, Eisen EA, Hu X, et al. (1994) Acute and chronic respiratory effects of sodium borate particulate exposures. Environ Health Perspect; 102: 119–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild P, Perdrix A, Romazini S, et al. (2000) Lung cancer mortality in a site producing hard metals. Occup Environ Med; 57: 568–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woskie SR, Shen P, Finkel M, et al. (1993) Calibration of a continuous-reading aerosol monitor (Miniram) to measure borate dust exposures. Appl Ind Hyg; 8: 38–45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.