Abstract

Objective

Passive administration of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) has been shown to protect against both vaginal and rectal challenge in the SHIV/macaque model of HIV transmission. However, the relative efficacy of antibody against the two modes of exposure is unknown and, given differences in the composition and immunology of the two tissue compartments, this is an important gap in knowledge. To investigate the significance of the challenge route for antibody-mediated protection, we performed a comparative protection study in macaques using the highly potent human monoclonal antibody, PGT126.

Design

Animals were administered PGT126 at three different doses before challenged either vaginally or rectally with a single dose of SHIVSF163P3.

Methods

Viral loads, PGT126 serum concentrations and serum neutralizing titers were monitored.

Results

In vaginally challenged animals, sterilizing immunity was achieved in all animals administered 10 mg/kg, in two of five animals administered 2 mg/kg and in one of five animals administered 0.4 mg/kg PGT126. Comparable protection was observed for the corresponding groups challenged rectally as sterilizing immunity was achieved in three of four animals administered 10 mg/kg, in two of four animals administered 2 mg/kg and in none of four animals administered 0.4 mg/kg PGT126. Serological analysis showed similar serum concentrations of PGT126 and serum neutralization titers in animals administered the same antibody dose.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that bnAb-mediated protection is not strongly dependent on the mucosal route of challenge, which indicates that a vaccine aimed to induce a neutralizing antibody response would have broadly similar efficacy against both primary transmission routes for HIV.

Keywords: HIV, mucosal transmission, neutralizing antibodies, Vaccine

Introduction

The mechanism of action for protection of most vaccines against human pathogens is believed to be elicitation of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) and this is therefore also a highly sought after property in a vaccine against HIV [1-4]. Indeed, numerous studies in macaques and humanized mice have shown that nAbs can provide sterilizing immunity against challenge with simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) and HIV [4-23]. In particular, it has been shown that broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) can induce sterilizing immunity against mucosal challenge of SHIVs, which in addition to active vaccination also suggests a potential role for bnAbs in passive immunization strategies against HIV [5-13,23].

Much has been learned about the conditions for HIV nAb protection against virus challenge in the last few years in both macaques and humanized mice. Antibody (Ab) titration studies have indicated that sterilizing immunity is achieved at serum Ab concentrations in the approximate range of 10 to a few hundred-fold times in vitro serum neutralizing titers [6,9-11,13,16,18,21,24,25]. The precise numbers clearly depend upon the neutralization assay used but even allowing for this factor, there do appear to be some differences between different Abs [5,8,10,26]. To ensure infection of all of the control animals the viral inoculum in the studies quoted, “high dose” challenge experiments, are typically several logs higher than is generally observed in human semen [27]. Data from a repeated “low-dose” SHIV/macaque challenge study showed protection at notably lower serum Ab neutralizing titers suggesting that sterilizing immunity in human exposure may be more readily achievable than predicted by the high-dose challenge studies [28]. Experiments, first in macaques and then in humanized mice have also indicated that FcR-mediated activities contribute to the protective activity of bnAbs against HIV challenge [24,28-30]. Furthermore, potent bnAbs have been shown to have dramatic effects on controlling virus in established infection, first in humanized mice, and then in macaques [31-33].

Despite the advances, significant gaps remain in our knowledge of Ab protection against HIV, most notably the time and location of Ab interception of virus is not well understood. One study using an intravenous SHIV challenge showed that administration of a polyclonal preparation of nAbs 6 hours but not 24 hours after challenge conferred protection [22]. In mucosal transmission, this time dependence of Ab-mediated protection might be increased if systemic infection is preceded by local propagation and expansion in the vaginal or rectal tissues as has been proposed [34-36]. Interestingly, a recent study suggested that protection by a live attenuated SIV vaccine correlated with local recruitment of gp41-specific IgG producing plasma cells in the vaginal tissue indicating a potential first line of defense by Abs [37].

In humans, the transmission rate through rectal exposure is at least 17 times higher than through vaginal exposure, which has been related to the immunology and architecture of the two tissues [35,36,38,39]. At present, the relative efficacy of Ab against transmission via the two modes of exposure is unknown. One recent study compared the two mucosal challenge routes but only for a single dose of Ab and all animals in both groups were protected [10]. Here, by comparison of three bnAb doses against a single vaginal or rectal viral challenge we seek to investigate whether the route of viral transmission strongly influences the efficacy of Ab-mediated protection in rhesus macaques.

Methods

Macaques

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol for the vaginal challenge study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Bioqual Inc. and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The protocol for the rectal challenge study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University. A total of 35 animals were used, 19 in the vaginal challenge experiment (5 animals per human Ab PGT126 treatment group, 4 control animals) and 16 in the rectal challenge experiment (4 animals per PGT126 treatment group, 4 control animals). All Ab infusions, viral challenges and sample collections were performed under ketamine or ketamine/telezol induced anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering. Virus challenge and i.v. Ab protocols are described elsewhere [6,7]. Briefly, Abs were infused slowly in the saphenous vein one day prior to viral challenge. Intrarectal challenge was performed on animals placed in a prone position with the hips supported. The viral inoculum was delivered atraumatically by a syringe inserted approximately 4 cm into the rectum. Following procedure, the syringe was examined for any sign of blood, which would indicate mucosal trauma. The animals were returned to their cages in a prone position (to prevent leakage of viral inoculum) and allowed to recover. Intravaginal challenge was performed on animals with the perineum slightly elevated. The viral inoculum was delivered atraumatically using an 8 french pediatric feeding tube attached to a syringe barrel. The animals were maintained with the perineum slightly elevated for 15 minutes before being returned to their cages and allowed to recover. All animals were monitored at least once daily for evidence of pain or distress. Plasma and serum samples were obtained throughout the studies and analyzed for viral load, PGT126 concentration and serum neutralizing titer. Animals in the vaginal challenge experiment were given 30 mg medroxy-progesterone (Depo-Provera) i.m. 28 days prior to the day of challenge to thin the vaginal tissue and synchronize menstrual cycles. At the start of the experiments, all animals were experimentally naive and were negative for Abs against HIV-1, SIV, and type D retrovirus. All animals were negative for the Mamu-B*08 and Mamu-B*17 alleles associated with spontaneous virologic control. Eight of the intrarectally challenged animals were Mamu-A*01 positive and were evenly distribution across treatment groups..

Challenge virus

The challenge virus was the tier 2 SHIVSF162 passage 3 virus [42,43] and was propagated in phytohemagglutinin-activated rhesus macaque PBMC. The original stock was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (catalog number 6526; contributors Drs. J. Harouse, C. Cheng-Mayer and R. Pal). The challenge dose was 300 TCID50 for both exposure routes.

Antibody production

Ab production was carried out as previously described [29,40]. In brief, Abs were generated in CHO-K1 cells and purified by Protein A affinity chromatography. PGT126 is a bnAb which recognizes the high-mannose patch on HIV gp120 [40-42]. DEN3, a dengue virus NS1-specific Ab was used as the isotype control Ab in the animal studies. Abs contained less that 0.03 EU/mg endotoxins.

ELISA

Serum PGT126 concentrations were determined by a HIVJRCSF gp120-specific ELISA as previously described for HIVJRFL gp120 [6]. In brief, 96 well microplates were coated with 2 ug/ml recombinant HIVJRCSF gp120 over night. Following a wash- and blocking step, serial dilution of serum samples or purified Abs were added to the plate. After incubation and a wash step, binding was detected with a goat anti-human IgG F(ab’)2 fragment coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Pierce) and visualized with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich).

Neutralization assay

Ab and serum neutralization titers were determined using the TZM-bl assay as previously described [43]. In brief, virus and Abs/serum were mixed and incubated for 1 hour before being added to TZM-bl cell in 96 well plates. DEAE-Dextran was added at a final concentration of 10 ug/ml (Sigma-Aldrich). Forty-eight hours after infections, cells were lysed and luciferase expression was quantified using the Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Pseudovirus was generated in 293T cells and SHIVSF162P3 was propagated in phytohemagglutinin-activated rhesus macaque PBMC.

Statistical analyses

Rectal and vaginal challenges were compared by Fisher's exact test [44] using GraphPad Prism 6 software package (GraphPad) and by logistic regression analysis using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC). Power analysis for the Fisher's exact test as implemented in R statistical package (http://rpackages.ianhowson.com/cran/statmod/man/power.html).

Results

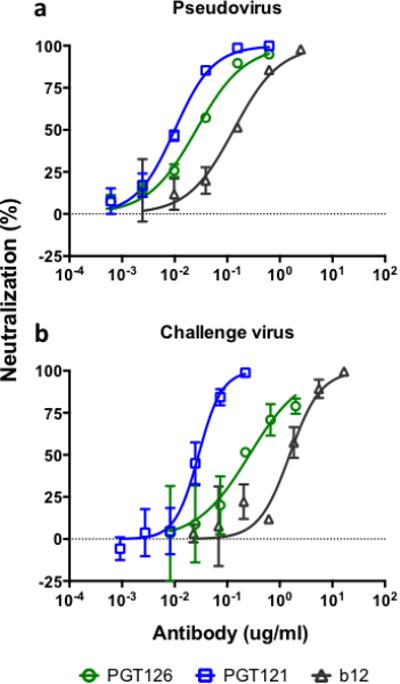

PGT126 potently neutralizes the challenge virus SHIVSF162P3 in vitro

Prior to carrying out an in vivo protection study using the bnAb PGT126, we determined the in vitro potency of the Ab against the challenge virus strain SHIVSF162P3. For comparison, we included PGT121 and b12, two Abs previously tested in protection studies against this virus [6,9]. The TZM-bl based neutralization assay was performed using both single round pseudovirus and full-length replication competent virus (the challenge stock). In the pseudovirus assay, PGT126 had an IC50 of 0.03 ug/ml whereas PGT121 and b12 had IC50s of 0.01 and 0.1 ug/ml, respectively (Fig. 1a). In the replication competent assay, PGT126 had an IC50 of 0.3 ug/ml whereas PGT121 and b12 had IC50s of 0.03 and 1.6 ug/ml, respectively (Fig. 1b). The two assays demonstrated that PGT126 neutralized SHIVSF162P3 with a potency between that of PGT121 and b12.

Fig. 1.

Neutralization of SHIVSF162P3 by PGT126. The TZM-bl assay was performed using SHIVSF162P3 (a) pseudovirus and (b) full-length replication competent virus (challenge stock). Both assays show efficient neutralization by PGT126 with a potency between PGT121 and b12. In the pseudovirus assay IC50s for PGT126, PGT121 and b12 were 0.03 ug/ml, 0.01 ug/ml and 0.1 ug/ml, respectively. In the replication competent virus assay IC50s for PGT126, PGT121 and b12 were 0.3 ug/ml, 0.03 ug/ml and 1.6 ug/ml, respectively. Values are mean and standard deviation of 4 wells. The assay was performed twice with similar results.

PGT126 protects against vaginal and rectal challenge of SHIVSF162P3 with comparable efficiency in vivo

To compare Ab-mediated protection against vaginal and rectal challenge, we performed a three-dose PGT126 titration protection study. The Ab doses were the same for the vaginal and rectal challenged groups and the animals received either 10 mg/kg of PGT126, 2 mg/kg of PGT126, 0.4 mg/kg of PGT126 or 10 mg/kg of an isotype control Ab. Abs were administered 24 hours prior to a single challenge of SHIVSF162P3. The challenge dose, based on a previous in vivo titration of the virus stock, was chosen as the lowest dose that would enable infection of all control animals. Comparable levels of protection were observed for vaginally and rectally challenged animals administered the same dose of PGT126 (Fig. 2). In the vaginally challenged animals, sterilizing immunity (defined here as no detectable viremia) was observed in all animals administered 10 mg/kg of PGT126, in 3 out of 5 animals administered 2 mg/kg of PGT126 and in 1 out of 5 animals administered 0.4 mg/kg of PGT126 (Fig. 2a). In the rectally challenged animals, sterilizing immunity was observed in 3 out of 4 animals administered 10 mg/kg of PGT126, in 2 out of 4 animals administered 2 mg/kg of PGT126 and in none of the four animals administered 0.4 mg/kg of PGT126 (Fig. 2b). Regardless of the challenge route, all animals administered the isotype control Ab became infected as expected. Comparison by Fisher's exact test and logistic regression analysis showed no statistically significant association between protection and the type of the challenge for any of the Ab dose groups (See Supplementary Information text for discussion and limitations of statistically analysis).

Fig. 2.

Plasma viral loads in macaques passively administered PGT126 or DEN3 mAbs before being challenged with a single dose of SHIVSF162P3. (a) Plasma viral loads for animals challenged vaginally 24 hours after being administered 10 mg/kg of PGT126 (green), 2 mg/kg of PGT126 (black), 0.4 mg/kg of PGT126 (blue) or 10 mg/kg of the isotype control DEN3 (red). All animals receiving 10 mg/kg were protected and showed no detectable viremia, three out of five became infected in the 2 mg/kg treatment group and four out of five became infected in the 0.4 mg/kg treatment group. (b) Plasma viral loads for animals challenged rectally 24 hours after being administered 10 mg/kg of PGT126 (green), 2 mg/kg of PGT126 (black), 0.4 mg/kg of PGT126 (blue) or 10 mg/kg of the isotype control DEN3 (red). One out of four animals receiving 10 mg/kg became infected, two out of four became infected in the 2 mg/kg treatment group and four out of four became infected in the 0.4 mg/kg treatment group. All animals given the isotype control antibody became viremic regardless of being vaginally or rectally challenged. Viral detection limit was 50 copies/ml and 60 copies/ml for the vaginal and rectal challenge experiments, respectively.

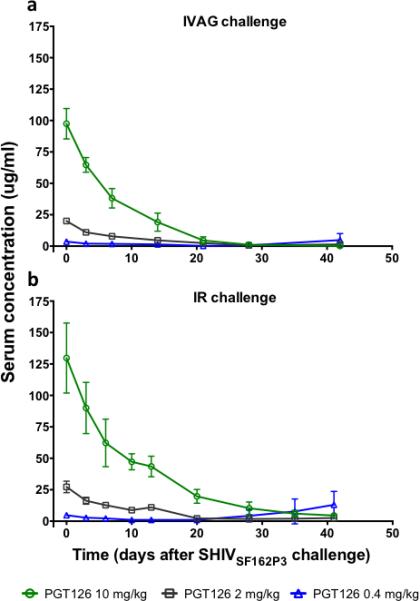

Serum concentrations and neutralizing titers were comparable between vaginally and rectally challenged animals administered the same antibody dose

Serum samples were analyzed at the time of challenge and PGT126 concentrations at the different dose levels were in similar ranges for the two sets of challenge experiment as expected (Fig. 3). Based on the longitudinal serum concentrations, an in vivo half-life in rhesus macaques for PGT126 was determined by fitting the slope to a one phase exponential decay (starting on day four to account for initial distribution). A combined half-life was calculated to be 6.3 days having slightly higher numbers in the rectally challenged animals (averaging 7.1 days) compared to vaginally challenged animals (averaging 5.5 days).

Fig. 3.

Serum concentrations of PGT126 in animals passively administered the antibody prior to SHIVSF162P3 challenge. Concentrations were determined at day 0 (day of challenge) through day 42 post-challenge by a HIV gp120-specific ELISA for (a) vaginally challenged animals and (b) rectally challenged animals. At the time of challenge, corresponding antibody dosing groups of vaginal and rectal challenged animals had comparable serum concentration of PGT126 as vaginally challenged animals given 10 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg and 0.4 mg/kg had average serum concentrations of 98 ug/ml, 20 ug/ml and 3.6 ug/ml, respectively, and rectally challenged animals given 10 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg and 0.4 mg/kg had average serum concentrations of 130 ug/ml, 27 ug/ml and 4.8 ug/ml, respectively. Serum concentrations are plotted as mean and standard deviation for each treatment group. Each time point represents the average of two measurements.

Using the TZM-bl assay, serum neutralization titers were determined at the time of challenge and up to seven days post challenge (Table 1). At the time of challenge, average serum neutralizing IC50 titers (reciprocal dilution) for the vaginally challenged animals were 2017, 251 and 56 for the 10 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg and 0.4 mg/kg groups, respectively, whereas the average serum neutralizing IC50 titers (reciprocal dilution) for the rectally challenged animals were 2448, 509, and 73 for the 10 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg and 0.4 mg/kg, respectively. Serum concentrations and serum neutralizing titers corresponded very well as the calculation of a serum IC50 concentration of PGT126 showed an average serum IC50 of 0.06 ug/ml (serum concentration divided by the serum dilution resulting in 50% inhibition) compared to 0.03 ug/ml obtained using purified PGT126 (Fig. 1a). Together, the data demonstrate comparable pharmacokinetics between the vaginally and rectally challenged animals administered the same Ab dose.

Table 1.

Neutralizing antibody titers in sera

| Neutraling titers, IC50 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Dose | Animal | Day0 | Day3 | Day6/7 |

| IVAG | 10mg/kg | 11-001 | 2372 | 1939 | 1000 |

| 11-007 | 1977 | 1477 | 751 | ||

| 11-009 | 2447 | 1484 | 823 | ||

| 11-015 | 1912 | 658 | 923 | ||

| 11-017 | 1378 | 457 | 127 | ||

| 2mg/kg | 11-059 | 109 | 56 | <50 | |

| 11-063 | 174 | 110 | 70 | ||

| 11-065 | 293 | 217 | 79 | ||

| 11-067 | 254 | 219 | 93 | ||

| 11-069 | 427 | 279 | 169 | ||

| 0.4mg/kg | 11-071 | 50 | <50 | <50 | |

| 11-073 | 51 | <50 | <50 | ||

| 11-075 | 75 | <50 | <50 | ||

| 11-077 | <50 | <50 | <50 | ||

| 11-079 | 46 | <50 | <50 | ||

| IR | 10mg/kg | RAs14 | 2354 | 1333 | 954 |

| RMm14 | 2838 | 1333 | 968 | ||

| REn14 | 1839 | 1387 | 928 | ||

| RPr14 | 2761 | 1731 | 450 | ||

| 2mg/kg | ROt14 | 328 | 181 | 123 | |

| RFr14 | 798 | 443 | 257 | ||

| RNg14 | 462 | 289 | 153 | ||

| RQg14 | 451 | 233 | 180 | ||

| 0.4mg/kg | RAo14 | 52 | <50 | <50 | |

| RYt14 | 71 | <50 | <50 | ||

| RQr14 | 96 | 52 | <50 | ||

| RPn14 | <50 | <50 | <50 | ||

Numbers represent reciprocal dilution of serum producing 50% neutralization.

Days after antibody administration, day 0 is the day of challenge.

Discussion

Passive transfer of bnAbs has been shown to protect rhesus macaques against both vaginal and rectal SHIV challenge [5-11,13]. However, the two tissue compartments vary considerably and to our knowledge, no study has directly addressed whether the challenge route strongly impacts the protective potency of bnAbs. Using the bnAb PGT126, we performed an Ab dose titration experiment against vaginal and rectal challenge of SHIVSF162P3 in rhesus macaques and found no significant difference in the protective ability of the Ab against the two challenge routes. We note that we used a relatively large number of animals (35 animals) to make this finding. To unambiguously prove that the protection is identical for the two challenge routes would require a much larger number of animals, 100+ macaques (Supplementary Information text).

Evidence suggests that rectal exposure to HIV contains a higher risk of viral transmission and faster viral dissemination than vaginal exposure, which has been associated with significant differences between the two tissues [35,36,38,39]. However, the exact time and place for Ab interception of virus is not known. If the “window of opportunity” for preventing infection is considered to be during the initial replication and expansion in the mucosal tissue [39] then our results are consistent with a similar Ab biodistribution between vaginal and rectal tissues. A direct investigation of these tissues was beyond the scope of the present study because of the number of animals available. However, recent studies do suggest that the level of Ab is roughly similar in vaginal and rectal tissues following intravenous administration and should therefore in principle be equivalently available in both tissues for neutralizing incoming virus [11,12]. Infused Abs can also be detected in mucosal secretions but the levels appear to be less consistent than those found in tissues and the sampling process entails a risk of bleeding and thereby a potential higher risk of infection [6,8,9,12,13,23,32,45]. Our results are equally consistent with bnAb interception of the virus occurring beyond initial replication in the mucosal tissue, for example in the blood or lymphatic system when the challenge route would be anticipated to have a minimal role. However, it is worth noting that systemically administrated neutralizing Abs can prevent viral infection of mucosal tissue as shown in several animal models of HPV infection [46,47] indicating significant transfer of Abs between the two compartments. Overall, further studies looking directly at the location of both Ab and virus following co-administration/challenge are needed to clarify the location of Ab interception of virus.

A caveat of the present study worth considering is the use of Depo-Provera in the vaginally challenged animals. The vaginal epithelium of rhesus macaques is much more keratinized than humans and Depo-Provera treatment, in addition to synchronizing the menstrual cycle, thins the epithelium, reportedly to similar levels of thickness observed in the human luteal phase [48,49]. The main concern about using Depo-Provera in passive Ab transfer studies has been that the epithelium is so thinned that the virus can transmit more easily than in human exposure. However, the applied dose (mg/kg) is in the range of that given for contraceptive use in humans and the number of transmitted/founder viruses does not appear to be increased in Depo-Provera treated animals compared to that observed in humans [48-51]. In addition, without hormonal treatment the challenge dose would need to be increased substantially from a dose (300 TCID50) already 1-2 logs higher than the range normally seen in human semen [27,48]. Overall, we believe that the Depo-Provera model serves as the best compromise for this study but realize that it entails a risk of underestimating the barriers for vaginal transmission.

PGT126 is part of the group of bnAbs that recognizes the high-mannose patch centered around the glycan at position N332 on gp120 [40-42,52,53]. PGT121 is also a member of this group and we recently showed efficient protection against vaginal challenge as well as strong suppression of viremia in an established infection [9,31]. The in vitro activity of PGT126 against the SHIVSF162P3 challenge virus is 10 fold lower than PGT121 (Fig 1b). This difference in vitro correlated well with the difference we found in the in vivo activity of the two Abs. In the present study, PGT126 protected 3 out of 5 animals against vaginal challenge at an administered Ab dose of 2 mg/kg (Fig. 2a) whereas, in our previous study, PGT121 protected the same number of animals (3 out of 5) at a 10-fold lower administered Ab dose of 0.2 mg/kg [9]. In the present study, average serum neutralizing titers of 251 and 509 protected 60% (3 out of 5) of the vaginal challenged animals and 50% (2 out of 4) of the rectal challenged animals, respectively. These numbers correlate well with our PGT121 passive protection study as an average serum neutralizing titer of 285 protected 60% (3 out of 5) of the animals challenged vaginally with SHIVSF162P3 [9]. Two other studies, one a comprehensive study based on rectal challenge of 60 macaques, have used a probit regression model to calculate that serum neutralizing titers of 104 and 235 would be protective of 50% of the challenged animals [11,25]. It should be noted that these analysis were based on virus pseudotyped with the challenge virus’ envelope and not the challenge virus itself. Nevertheless, collectively these studies strongly suggest, as previously stated [9,11], that protective titers against HIV may be achievable if elicitation of Abs with similar potencies as the ones used in these studies can be achieved by vaccination.

In summary, our findings noted no major differences in the ability of the bnAb PGT126 to protect against vaginal or rectal challenge in the SHIV/macaque model. The results are consistent with the notion that bnAbs, either induced by vaccination or used as immunoprophylaxis, will have broadly similar efficacy against both primary transmission routes for HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Virology core for their technical support and the CHAVI-ID DMSRC (Data management scientific research component) and Arne Haahr Andreasen for help with the statistical analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH/CHAVI-ID grant UM1 AI100663, NIH/NCRR grant P51RR000165, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation/International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) Neutralizing Antibody Consortium grants SFP 2120 and SFP 2121. The Yerkes National Primate Research Center was supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs/OD P51OD011132.

Footnotes

Author contributions: B.M., D.G.C., G.S., D.H.B., and D.R.B. designed research; B.M., K.L., D.G.C., J.B.W., N.S., M.G.L., E.B., K.S., J.J.M., and S.L.S., performed research; B.M., A.P.H., A. G., P.W.H.I.P, and D.R.B. analyzed data; and B.M. and D.R.B. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Plotkin SA. Correlates of Protection Induced by Vaccination. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2010;17:1055–1065. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton DR, Poignard P, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Present New Prospects to Counter Highly Antigenically Diverse Viruses. Science. 2012;337:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1225416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mascola JR, Montefiori DC. The Role of Antibodies in HIV Vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton DR, Mascola JR. Antibody responses to envelope glycoproteins in HIV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:571–576. doi: 10.1038/ni.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascola JR, Stiegler G, VanCott TC, Katinger H, Carpenter CB, Hanson CE, et al. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nature Medicine. 2000;6:207–210. doi: 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parren PW, Marx PA, Hessell AJ, Luckay A, Harouse J, Cheng-Mayer C, et al. Antibody protects macaques against vaginal challenge with a pathogenic R5 simian/human immunodeficiency virus at serum levels giving complete neutralization in vitro. J Virol. 2001;75:8340–8347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8340-8347.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Tehrani DM, Huber M, Weisgrau KL, Landucci G, et al. Broadly Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 Directed against the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 gp41 Membrane-Proximal External Region Protect against Mucosal Challenge by Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus SHIVBa-L. J Virol. 2010;84:1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Poignard P, Hangartner L, Landucci G, Forthal DN, et al. Broadly Neutralizing Human Anti-HIV Antibody 2G12 Is Effective in Protection against Mucosal SHIV Challenge Even at Low Serum Neutralizing Titers. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000433. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moldt B, Rakasz EG, Schultz N, Chan-Hui P-Y, Swiderek K, Weisgrau KL, et al. Highly potent HIV-specific antibody neutralization in vitro translates into effective protection against mucosal SHIV challenge in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214785109. Published Online First: 25 October 2012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1214785109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pegu A, Yang ZY, Boyington JC, Wu L, Ko SY, Schmidt SD, et al. Neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 envelope protect more effectively in vivo than those to the CD4 receptor. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6:243ra88–243ra88. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shingai M, Donau OK, Plishka RJ, Buckler-White A, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, et al. Passive transfer of modest titers of potent and broadly neutralizing anti-HIV monoclonal antibodies block SHIV infection in macaques. Journal of Experimental Medicine. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132494. Published Online First: 25 August 2014. doi:10.1084/jem.20132494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko S-Y, Pegu A, Rudicell RS, Yang Z-Y, Joyce MG, Chen X, et al. Enhanced neonatal Fc receptor function improves protection against primate SHIV infection. Nature. 2014:1–16. doi: 10.1038/nature13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudicell RS, Kwon YD, Ko SY, Pegu A, Louder MK, Georgiev IS, et al. Enhanced Potency of a Broadly Neutralizing HIV-1 Antibody In Vitro Improves Protection against Lentiviral Infection In Vivo. J Virol. 2014;88:12669–12682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02213-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mascola JR, Lewis MG, Stiegler G, Harris D, VanCott TC, Hayes D, et al. Protection of Macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 1999;73:4009–4018. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4009-4018.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba TW, Liska V, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Vlasak J, Xu W, Ayehunie S, et al. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nature Medicine. 2000;6:200–206. doi: 10.1038/72309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauduin MC, Parren PW, Weir R, Barbas CF, Burton DR, Koup RA. Passive immunization with a human monoclonal antibody protects hu-PBL-SCID mice against challenge by primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature Medicine. 1997;3:1389–1393. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gauduin M-C, Safrit JT, Weir R, Fung MS, Koup RA. Pre-and postexposure protection against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection mediated by a monoclonal antibody. J INFECT DIS. 1995;171:1203–1209. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parren PW, Ditzel HJ, Gulizia RJ, Binley JM, Barbas CF, Burton DR, et al. Protection against HIV-1 infection in hu-PBL-SCID mice by passive immunization with a neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against the gp120 CD4-binding site. AIDS. 1995;9:F1–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safrit JT, Fung MS, Andrews CA, Braun DG, Sun WN, Chang TW, et al. hu-PBL-SCID mice can be protected from HIV-1 infection by passive transfer of monoclonal antibody to the principal neutralizing determinant of envelope gp120. AIDS. 1993;7:15–21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata R, Igarashi T, Haigwood N, Buckler-White A, Ogert R, Ross W, et al. Neutralizing antibody directed against the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein can completely block HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus infections of macaque monkeys. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:204–210. doi: 10.1038/5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura Y, Igarashi T, Haigwood N, Sadjadpour R, Plishka RJ, Buckler-White A, et al. Determination of a Statistically Valid Neutralization Titer in Plasma That Confers Protection against Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Challenge following Passive Transfer of High-Titered Neutralizing Antibodies. J Virol. 2002;76:2123–2130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2123-2130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura Y, Igarashi T, Haigwood NL, Sadjadpour R, Donau OK, Buckler C, et al. Transfer of neutralizing IgG to macaques 6 h but not 24 h after SHIV infection confers sterilizing protection: implications for HIV-1 vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15131–15136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436476100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein K, Veazey RS, Warrier R, Hraber P, Doyle-Meyers LA, Buffa V, et al. Neutralizing IgG at the portal of infection mediates protection against vaginal SHIV challenge. J Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01361-13. Published Online First: 21 August 2013. doi:10.1128/JVI.01361-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pietzsch J, Gruell H, Bournazos S, Donovan BM, Klein F, Diskin R, et al. A mouse model for HIV-1 entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15859–15864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213409109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willey R, Nason MC, Nishimura Y, Follmann DA, Martin MA. Neutralizing antibody titers conferring protection to macaques from a simian/human immunodeficiency virus challenge using the TZM-bl assay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:89–98. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poignard P, Moldt B, Maloveste K, Campos N, Olson WC, Rakasz E, et al. Protection against High-Dose Highly Pathogenic Mucosal SIV Challenge at Very Low Serum Neutralizing Titers of the Antibody-Like Molecule CD4-IgG2. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klasse PJ, Shattock RJ, Moore JP. Which Topical Microbicides for Blocking HIV-1 Transmission Will Work in the Real World? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hessell AJ, Poignard P, Hunter M, Hangartner L, Tehrani DM, Bleeker WK, et al. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal SHIV challenge in macaques. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:951–954. doi: 10.1038/nm.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hessell AJ, Hangartner L, Hunter M, Havenith CEG, Beurskens FJ, Bakker JM, et al. Fc receptor but not complement binding is important in antibody protection against HIV. Nature. 2007;449:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature06106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bournazos S, Klein F, Pietzsch J, Seaman MS, Nussenzweig MC, Ravetch JV. Broadly Neutralizing Anti-HIV-1 Antibodies Require Fc Effector Functions for In Vivo Activity. Cell. 2014;158:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barouch DH, Whitney JB, Moldt B, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Liu J, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature12744. Published Online First: 30 October 2013. doi:10.1038/nature12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shingai M, Nishimura Y, Klein F, Mouquet H, Donau OK, Plishka R, et al. Antibody-mediated immunotherapy of macaques chronically infected with SHIV suppresses viraemia. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature12746. Published Online First: 30 October 2013. doi:10.1038/nature12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein F, Halper-Stromberg A, Horwitz JA, Gruell H, Scheid JF, Bournazos S, et al. HIV therapy by a combination of broadly neutralizing antibodies in humanized mice. Nature. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haase AT. Targeting early infection to prevent HIV-1 mucosal transmission. Nature. 2010;464:217–223. doi: 10.1038/nature08757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishimura Y, Martin MA. The acute HIV infection: implications for intervention, prevention and development of an effective AIDS vaccine. Current Opinion in Virology. 2011;1:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keele BF, Estes JD. Barriers to mucosal transmission of immunodeficiency viruses. Blood. 2011;118:839–846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Zeng M, Duan L, Voss JE, Smith AJ, Pambuccian S, et al. Live Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Vaccine Correlate of Protection: Local Antibody Production and Concentration on the Path of Virus Entry. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;193:3113–3125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel P, Borkowf CB, Brooks JT, Lasry A, Lansky A, Mermin J. Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk. AIDS. 2014;28:1509–1519. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haase AT. Early Events in Sexual Transmission of HIV and SIV and Opportunities for Interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:127–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-080709-124959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien J-P, et al. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, et al. A Potent and Broad Neutralizing Antibody Recognizes and Penetrates the HIV Glycan Shield. Science. 2011;334:1097–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.1213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sok D, Doores KJ, Briney B, Le KM, Saye-Francisco KL, Ramos A, et al. Promiscuous Glycan Site Recognition by Antibodies to the High-Mannose Patch of gp120 Broadens Neutralization of HIV. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6:236ra63–236ra63. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79:10108–10125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Handbook of Biological Statistics. 3rd ed. Sparky House Publishing; Baltimore, Maryland: 2014. http://books.google.com/books?id=AsRTywAACAAJ&dq=Handbook+of+Biological+Statistics&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moldt B, Shibata-Koyama M, Rakasz EG, Schultz N, Kanda Y, Dunlop DC, et al. A Nonfucosylated Variant of the anti-HIV-1 Monoclonal Antibody b12 Has Enhanced FcγRIIIa-Mediated Antiviral Activity In Vitro but Does Not Improve Protection against Mucosal SHIV Challenge in Macaques. J Virol. 2012;86:6189–6196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00491-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breitburd F, Kirnbauer R, Hubbert NL, Nonnenmacher B, Trin-Dinh-Desmarquet C, Orth G, et al. Immunization with viruslike particles from cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) can protect against experimental CRPV infection. J Virol. 1995;69:3959–3963. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3959-3963.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzich JA, Ghim SJ, Palmer-Hill FJ, White WI, Tamura JK, Bell JA, et al. Systemic immunization with papillomavirus L1 protein completely prevents the development of viral mucosal papillomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11553–11557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veazey RS, Shattock RJ, Klasse PJ, Moore JP. Animal models for microbicide studies. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10:79–87. doi: 10.2174/157016212799304715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNicholl JM, Henning TC, Vishwanathan SA, Kersh EN. Non-Human Primate Models of Hormonal Contraception and HIV. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:513–522. doi: 10.1111/aji.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burton DR, Hessell AJ, Keele BF, Klasse PJ, Ketas TA, Moldt B, et al. Limited or no protection by weakly or nonneutralizing antibodies against vaginal SHIV challenge of macaques compared with a strongly neutralizing antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11181–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103012108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Decker JM, Pham KT, Salazar MG, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, et al. Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2015;514:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, et al. Crystal Structure of a Soluble Cleaved HIV-1 Envelope Trimer. Science Published Online First. 2013 Oct 31; doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. doi:10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.