Abstract

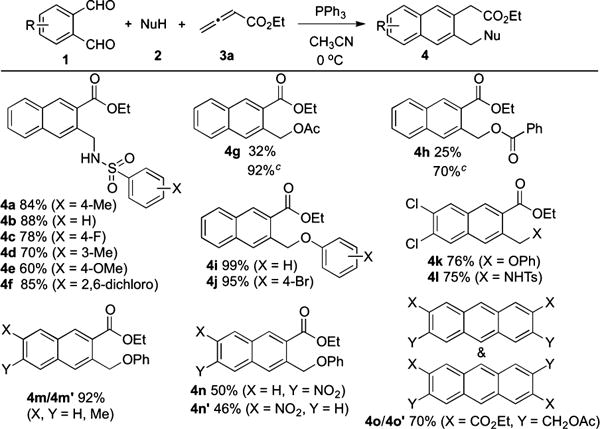

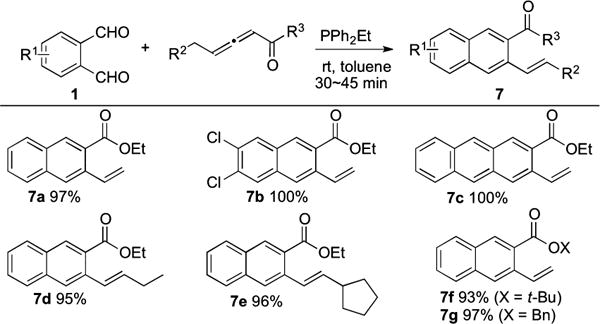

A PPh3-mediated multicomponent reaction between o-phthalaldehydes, nucleophiles, and monosubstituted allenes furnishes functionalized non-C2-symmetric naphthalenes in synthetically useful yields. When the Co-phthalaldehydes were reacted with 1,3-disubstituted allenes in the presence of PPh2Et, naphthalene derivatives were also obtained in up to quantitative yields. The mechanism of the latter transformation is straightforward: aldol addition followed by Wittig olefination and dehydration. The mechanism of the former is a tandem γ-umpolung/aldol/Wittig/dehydration process, as established by preparation of putative reaction intermediates and mass spectrometric analysis. This transformation can be applied iteratively to prepare anthracenes and tetracenes using carboxylic acids as pronucleophiles.

The reactivity of electron-deficient allenes under the conditions of phosphine catalysis has been investigated extensively.1 Many reports have appeared on the reactions of monosubstituted allenes with activated olefin2 and imine3 electrophiles to construct carbocyclic and azacyclic compounds. Contrarily, few examples of reactions between monosubstituted allenes and aldehyde electrophiles under the influence of phosphine catalysts are known.4 In general, the union of an allenoate and an aldehyde in the presence of a phosphine yields an olefin through a Wittig-like process.5 Interestingly, all such reports have described reactions between α- or γ-substituted allenoates and aldehydes. In contrast, Wittig reactions involving simple allenoates are rare. We know of only one example, in which intramolecular Wittig olefination of ethyl allenoate (3a) and pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde formed a pyrrolizine as a minor product (6%).6 Here we report Wittig olefination between monosubstituted allenes and o-phthalaldehydes to give highly functionalized naphthalenes and higher-order acenes.

Functionalized naphthalenes are valuable building blocks for the synthesis of many important small molecules (e.g., pharmaceuticals, chiral reagents, liquid crystals, organic dyes). Many recent syntheses of functionalized naphthalenes employ costly transition metals or require several steps to prepare the starting materials.8 Our phosphine-mediated multicomponent cascade reaction described herein—between o-phthalaldehydes, nucleophiles, and monosubstituted allenes—is an efficient and mild method for synthesizing functionalized naphthalenes from readily available starting materials.

We surveyed the reaction between 3a, o-phthalaldehyde (1a), and p-toluenesulfonamide by varying the phosphine (stoichiometric), the solvent, the ratio of the reactants, the reaction temperature, and the concentration.9 The optimized reaction conditions featured PPh3 (1 equiv) as the mediator, an o-phthalaldehyde (1 equiv), a nucleophile (2 equiv), and ethyl allenoate (3 equiv) in CH3CN at 0 °C.

Tables 1 and 2 reveal the scope of this three-component cascade reaction. As the nucleophilic component, benzenesulfonamides bearing electron-withdrawing or -donating substituents generated naphthalene derivatives 4a—f in high yields (Table 1). With acetic acid and benzoic acid as nucleophiles, the reactions were inefficient, giving low yields of naphthalene derivatives 4g and 4h, respectively. Adding an equimolar amount of sodium acetate or sodium benzoate as a buffer improved the yields of 4g and 4h dramatically.10 When phenol and p-bromophenol were used as the nucleophiles, the naphthalene derivatives 4i and 4j, respectively, were formed quantitatively. Examining substituted phthalaldehydes, we found that 4,5-dichloro-o-phthalaldehyde also participated in the reaction, furnishing naphthalene derivatives 4k and 4l in good yields. Asymmetric 4-methyl-o-phthalaldehyde furnished the inseparable isomers 4m and 4m′ in 92% yield. When 4-nitro-o-phthalaldehyde was used, we separated the two isomers 4n and 4n′ in 50 and 46% yield, respectively.11 Lastly, the combination of benzene-1,2,4,5-tetracarbaldehyde and acetic acid resulted in the expected anthracenes 4o and 4o′ in a combined yield of 70%.12

Table 1.

|

The reactions were performed by adding 3 (1.5 mmol) in CH3CN (8 mL) via syringe pump (2 mL/h) at 0 °C to a solution of 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (1 mmol), and PPh3 (0.5 mmol) in CH3CN (4 mL).

Isolated yields are shown.

Sodium carboxylate (1 mmol) was added.

Table 2.

Arene Homologation Using Phthalaldehyde (1a)a,b

|

See Table 1, footnotes a and b.

NaOAc (1 mmol) was added.

We further investigated the reaction scope by treating 1a with a suite of allenes and nucleophiles (Table 2). The reaction of p-toluenesulfonamide and benzyl allenoate provided naphthalene 4p quantitatively, while that of p-nitrobenzenesulfonamide produced 4q in only 40% yield, presumably because of attenuated nucleophilicity. Adding NaOAc as a buffer improved the yield of 4r from 34 to 85%.10 2-(Trimethylsilyl)ethyl buta-2,3-dienoate/p-toluenesulfonamide and 2,6-dimethylphenyl buta-2,3-dienoate/phenol produced the desired products 4s (87%) and 4t (73%), respectively. The reaction of penta-3,4-dien-2-one and phenol gave 4u in 98% yield.

While phosphine-catalyzed γ-umpolung additions of nucleophiles to allenoates (eq 1) have been documented amply,10,13

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

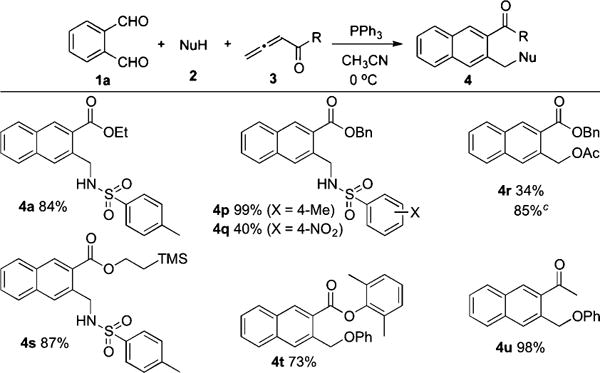

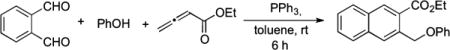

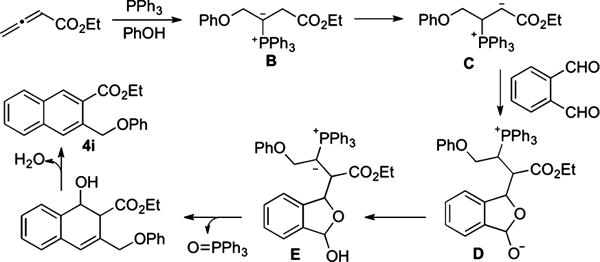

reactions between monosubstituted allenes and aldehydes other than salicylaldehyde (derivatives) have been scarce.4a–e In those limited examples, the phosphonium dienolate A adds to the aldehyde at its γ-carbon (eq 2). On the basis of this prior knowledge, we postulated a credible process involving a sequence of γ-umpolung addition, aldol reaction, Wittig olefination, and dehydration (Scheme 1). Here the ylide intermediate B from the initial γ-umpolung addition undergoes proton transfer to form phosphonium enolate C, which adds to 1a to form lactolate D. Proton transfer forms ylide E, which undergoes Wittig olefination. Subsequent dehydration provides naphthalene 4i. Notably, only the γ-umpolung addition product was obtained when 1a was replaced with benzaldehyde, suggesting that the phthalaldehyde plays a crucial role in the progression of the cascade sequence by forming the lactol substructure. Indeed, when we attempted to prepare the adduct between 1a and allenoate, we isolated the corresponding lactol product (see compound 6 in eq 5).

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

Scheme 1.

γ-Umpolung/Aldol/Wittig/Dehydration Sequence

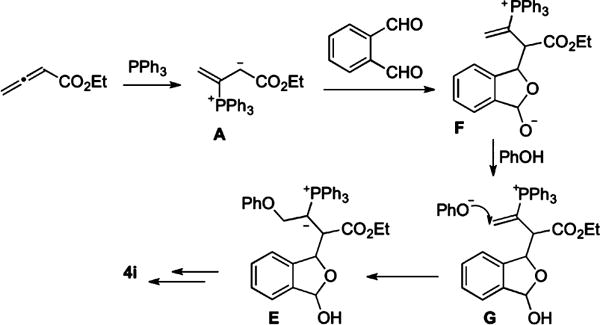

Although γ-umpolung addition/aldol reaction/Wittig olefination/dehydration is the likely sequence for the phthalaldehyde-to-naphthalene conversion, we could not exclude the alternative sequence of aldol/γ-umpolung/Wittig/dehydration (Scheme 2). In this scenario, phosphonium dienolate A adds to 1a to form phosphonium lactolate F. Deprotonation of phenol by lactolate provides the phenoxide nucleophile, γ-umpolung addition of which yields E, leading to intramolecular Wittig olefination and eventual formation of 4i.

Scheme 2.

Aldol/γ-Umpolung/Wittig/Dehydration Sequence

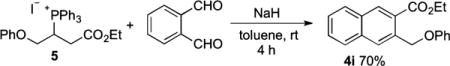

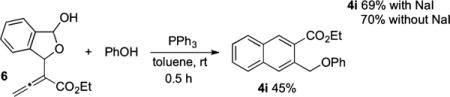

To establish which of the two possible mechanisms is more likely, we prepared phosphonium salt 5 (a precursor of B) and lactol 6 (a precursor of F).9 Mixing 5 with NaH (1 equiv) and 1a (1 equiv) in toluene at room temperature for 4 h yielded naphthalene 4i in 70% isolated yield (eq 3). Because the optimized conditions for the three-component reaction differed from those of the reaction described above, we also ran the coupling reaction between 1a, 1 equiv of phenol, 1 equiv of the allenoate, 1 equiv of PPh3, and 1 equiv of NaI as an additive (eq 4). This reaction in toluene at room temperature went to completion within 6 h and produced naphthalene 4i in 69% isolated yield. Alternatively, when we mixed lactol allenoate 6 with PPh3 (1 equiv) and phenol (1 equiv) in toluene at room temperature, we obtained the expected product 4i in 45% yield within only 30 min (eq 5). A control reaction between 1a, phenol (1 equiv), 3a (1 equiv), and PPh3 (1 equiv) in toluene at room temperature afforded 4i in 70% isolated yield after 6 h (eq 4). Thus, the NaI additive had no effect on the coupling reaction.

Although inconclusive, the experiments in eqs 3–5 hinted at the following possibility. If the aldol reaction occurred before the umpolung reaction, the rate-limiting step for the scenario in Scheme 2 would be the addition of A to 1a because the conversion of 6 to the product took only 30 min. If the umpolung addition were the first event of the cascade reaction (i.e., Scheme 1), the conversion of B to C or the addition of C to 1a would likely be the slowest step. Indeed, the pKa of the B (21 in DMSO) is lower than that of C (30 in DMSO).14 Thus, despite unfavorable thermodynamics, phosphonium dienolate A is likely to be funneled into ylide B as a result of rapid protonation by acidic phenol and subsequent γ-addition (eq 1).

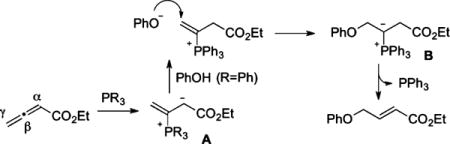

Consequently, we envisioned a reaction between an allenoate and 1a in the absence of a pronucleophile. We deduced that the presumed intermediate F′ might form ylide H, which should undergo facile intramolecular Wittig olefination and dehydration to form naphthalene 7a (eq 6). To our delight, the reaction

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

between 1a, ethyl 2,3-pentadienoate (1 equiv), and PPh3 (1 equiv) in toluene at room temperature for 50 min gave 7a in 75% isolated yield (eq 7). This outcome not only provides an alternative pathway for arene homologation but also discounts the aldol-before-γ-umpolung addition scenario. Since the γ-umpolung/Wittig/dehydration sequence of lactol 6 took 30 min and the aldol/Wittig/dehydration sequence of 1a and ethyl 2,3-pentadienoate (through intermediate F′) took 50 min, the three-component arene homologation would have been complete within 1 h if the reaction had occurred through the aldol-first route. Therefore, the reaction likely proceeds through initial γ-umpolung addition, with the rate-limiting step being the conversion of B to C rather than the aldol addition of C to 1a.

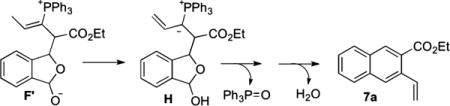

Monitoring the reaction with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) confirmed our suspicions (Figure 1). After a reaction time of 3 min (8.3% 4i formation), the HRMS trace displayed A ([M + H]+, m/z 375.1514) and B ([M + Na]+, m/z 491.1752) but no F ([M + H]+, m/z 509.1882).9 Although the reaction progressed steadily with the peak for B clearly present throughout, the peak corresponding to phosphonium lactolate F was barely evident after 40 min (37.5% 4i formation) and was clearly visible only after 4 h (63.2% 4i formation), suggesting that initial γ-addition is the dominant reaction pathway.

Figure 1.

HRMS spectra recorded during the reaction shown in eq 4 (without NaI). The m/z values are for [M + H]+ or [M + Na]+ ions.

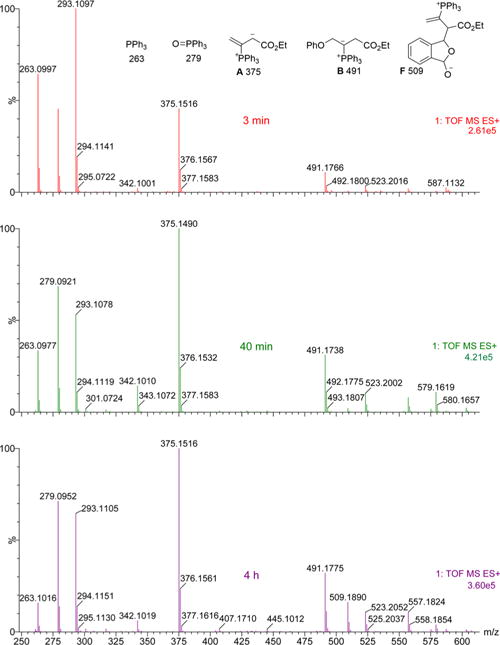

Examination of a range of phosphines, solvents, and reaction temperatures revealed that addition of the γ-substituted allenoate (2 equiv) to a mixture of the phthalaldehyde and PPh2Et (1 equiv) in toluene at room temperature was optimal for arene homologation (Table 3). After 30–45 min of stirring, the desired arenes 7a–g were obtained in excellent yields. 4,5-Dichloroph-thalaldehyde was converted quantitatively to naphthalene 7b. When naphthalene-2,3-dicarbaldehyde was used in this reaction, anthracene 7c was obtained in 100% isolated yield. Ethyl hexa-2,3-dienoate and ethyl 4-cyclopentylbuta-2,3-dienoate gave naphthalenes 7d and 7e, respectively, as E stereoisomers. tert-Butyl penta-2,3-dienoate and benzyl penta-2,3-dienoate gave the expected products 7f (93%) and 7g (97%), respectively.

Table 3.

|

The reactions were performed with 1 (0.4 mmol), allenoate (0.8 mmol), and PPh2Et (0.4 mmol) in toluene (4 mL) at room temperature.

Isolated yields are shown.

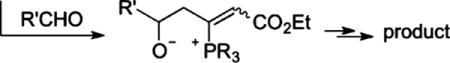

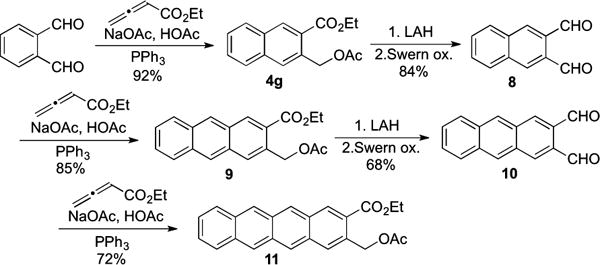

The utility of the multicomponent reaction is further illustrated by the synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted tetracene 11 (Scheme 3). Reduction of the ester groups of naphthalene 4g yielded a diol, which was oxidized to naphthalene-2,3-dicarbaldehyde (8) with high efficiency. Repetition of the annulation, reduction, and oxidation sequence provided anthracene-2,3-dicarbaldehyde (10), which underwent another annulation to provide tetracene 11. A variety of 2,3-substituted tetracenes should be readily obtainable from 11 through functional group manipulation, with potential applications in solar cells and light-emitting materials.15

Scheme 3.

Iterative Synthesis of Anthracene and Tetracene

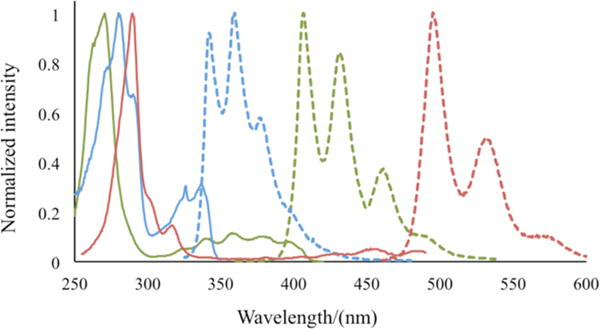

We obtained fluorescence excitation and emission spectra for compounds 4g, 9, and 11 (Figure 2). Stronger transitions appeared in the range 250–300 nm, with weaker transitions in the range 300–500 nm. A bathochromic shift occurred in going from 4g (326 nm) to 9 (358 nm) to 11 (450 nm). A bathochromic shift also occurred in the fluorescence emissions in going from 4g to 9 to 11, with 0–0 transitions at 342, 406, and 495 nm, respectively. The quantum yields for the substituted polyacenes 4g, 9, and 11 were 0.18, 0.65, and 0.15, respectively. These observations match well with reported photophysical data of 2-carbonylpolyacenes.16

Figure 2.

Excitation (solid lines) and emission (dashed lines) spectra of 4g (blue lines), 9 (green lines), and 11 (red lines).

In conclusion, we have developed a phosphine-mediated multicomponent reaction between allenes, o-phthalaldehydes, and nucleophiles that provides non-C2-symmetric naphthalene, anthracene, and tetracene derivatives. A mechanistic investigation involving the synthesis of putative intermediates and HRMS reaction monitoring revealed that this conversion occurs through a γ-umpolung addition/aldol/Wittig/dehydration cascade. A combination of phthalaldehydes and 1,3-disubstituted allenes also produces naphthalenes through an aldol/Wittig/dehydration sequence. This arene homologation can also be applied iteratively to prepare higher-order acenes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NIH (GM071779) is acknowledged for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b07403.

Experimental procedures and analytical data (PDF)

Crystallographic data for 4n′ (CIF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.For selected reviews, see:; (a) Lu X, Zhang C, Xu Z. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:535. doi: 10.1021/ar000253x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cowen BJ, Miller SJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3102. doi: 10.1039/b816700c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) López F, Mascareñas JL. Chem - Eur J. 2011;17:418. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhao QY, Lian Z, Wei Y, Shi M. Chem Commun. 2012;48:1724. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15793k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fan YC, Kwon O. Chem Commun. 2013;49:11588. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47368f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang Z, Xu X, Kwon O. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:2927. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00054d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected examples, see:; (a) Zhang C, Lu X. J Org Chem. 1995;60:2906. [Google Scholar]; (b) Du Y, Lu X, Yu Y. J Org Chem. 2002;67:8901. doi: 10.1021/jo026111t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lu X, Lu Z, Zhang X. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:457. [Google Scholar]; (d) Henry CE, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2007;9:3069. doi: 10.1021/ol071181d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu Z, Zheng S, Zhang X, Lu X. Org Lett. 2008;10:3267. doi: 10.1021/ol8011452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Guan X-Y, Wei Y, Shi M. Org Lett. 2010;12:5024. doi: 10.1021/ol102191p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Xiao H, Chai Z, Zheng CW, Yang YQ, Liu W, Zhang JK, Zhao G. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:4467. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Han X, Wang Y, Zhong F, Lu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1726. doi: 10.1021/ja1106282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Han X, Wang S-X, Zhong F, Lu Y. Synthesis. 2011;2011:1859. [Google Scholar]; (j) Zhao Q, Han X, Wei Y, Shi M, Lu Y. Chem Commun. 2012;48:970. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16904e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected examples, see:; (a) Xu Z, Lu X. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3461. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu Z, Lu X. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5031. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mercier E, Fonovic B, Henry CE, Kwon O, Dudding T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3617. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fang YQ, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5660. doi: 10.1021/ja801344w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Guan XY, Wei Y, Shi M. J Org Chem. 2009;74:6343. doi: 10.1021/jo9008832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Meng XT, Huang Y, Chen RY. Org Lett. 2009;11:137. doi: 10.1021/ol802453c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Sun YW, Guan XY, Shi M. Org Lett. 2010;12:5664. doi: 10.1021/ol102461c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Chen XY, Lin RC, Ye S. Chem Commun. 2012;48:1317. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16055b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Han X, Zhong F, Wang Y, Lu Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:767. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Henry CE, Xu Q, Fan YC, Martin TJ, Belding L, Dudding T, Kwon O. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11890. doi: 10.1021/ja505592h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Zhu XF, Henry CE, Wang J, Dudding T, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2005;7:1387. doi: 10.1021/ol050203y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dudding T, Kwon O, Mercier E. Org Lett. 2006;8:3643. doi: 10.1021/ol061095y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhu X-F, Schaffner A-P, Li RC, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2005;7:2977. doi: 10.1021/ol050946j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Creech GS, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2008;10:429. doi: 10.1021/ol702462w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Creech GS, Zhu XF, Fonovic B, Dudding T, Kwon O. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6935. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sun YW, Guan XY, Shi M. Org Lett. 2010;12:5664. doi: 10.1021/ol102461c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) He ZR, Tang V, He ZJ. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 2008;183:1518. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu SL, Zhou LL, Zeng S, Ma RQ, Wang ZH, He ZJ. Org Lett. 2009;11:3498. doi: 10.1021/ol901334c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu SL, Zou W, Wu GP, Song HB, He ZJ. Org Lett. 2010;12:3556. doi: 10.1021/ol101429z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Khong SN, Tran YS, Kwon O. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4760. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Xu SL, Chen RS, He ZJJ. Org Chem. 2011;76:7528. doi: 10.1021/jo201466k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Jacobsen MJ, Funder ED, Cramer JR, Gothelf KV. Org Lett. 2011;13:3418. doi: 10.1021/ol2011677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Qin Z, Ma R, Xu S, He ZJ. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:10424. [Google Scholar]; For exceptions, see parts (d) and (g) and:; (h) Ma RQ, Xu SL, Tang XF, Wu GP, He ZJ. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:1053. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virieux D, Guillouzic AF, Cristau HJ. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:3710. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Harvey RG. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Wiley-VCH; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]; (b) Watson MD, Fechtenkötter A, Müllen K. Chem Rev. 2001;101:1267. doi: 10.1021/cr990322p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) De Koning CB, Rousseau AL, van Otterlo WAL. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For selected examples, see:; (a) Feng C, Loh TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17710. doi: 10.1021/ja108998d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukutani T, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. J Org Chem. 2011;76:2867. doi: 10.1021/jo200339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kocsis LS, Benedetti E, Brummond KM. Org Lett. 2012;14:4430. doi: 10.1021/ol301938z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kang DL, Kim J, Oh S, Lee PH. Org Lett. 2012;14:5636. doi: 10.1021/ol302437v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Geary LM, Chen TY, Montgomery TP, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5920. doi: 10.1021/ja502659t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Pham MV, Cramer N. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:3484. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.See the Supporting Information (SI) for more details.

- 10.Trost BM, Li CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:3167. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The structure of 4ń was established using X-ray crystallography.9

- 12.The structures of 4o and 4o′ were identified using 1H NMR spectroscopy. See the detailed information in the SI.

- 13.For selected examples, see:; (a) Cristau H-J, Viala J, Christol H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:1569. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang C, Lu X. Synlett. 1995;645 [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen Z, Zhu G, Jiang Q, Xiao D, Cao P, Zhang X. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5631. doi: 10.1021/jo9623548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith SW, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14231. doi: 10.1021/ja9061823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chung YK, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:2225. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lundgren RJ, Wilsily A, Marion N, Ma C, Chung YK, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:2525. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans DA. Evans pKa Table. http://evans.harvard.edu/pdf/evans_pKa_table.pdf.

- 15.(a) Bendikov M, Wudl F, Perepichka DF. Chem Rev. 2004;104:4891. doi: 10.1021/cr030666m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anthony JE. Chem Rev. 2006;106:5028. doi: 10.1021/cr050966z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Burdett JJ, Bardeen CJ. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:1312. doi: 10.1021/ar300191w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nehira T, Parish CA, Jockusch S, Turro NJ, Nakanishi K, Berova N. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8681. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.