Abstract

Multiple new drugs are being developed to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML), including novel formulations of traditional chemotherapy-antibody drug conjugates and agents that target specific mutant enzymes. Next-generation sequencing has allowed us to discover the genetic mutations that lead to the development and clinical progression of AML. Studies of clonal hierarchy suggest which mutations occur early and dominate. This has led to targeted therapy against mutant driver proteins as well as the development of drugs such as CPX-351 and SGN-CD33A whose mechanisms of action and efficacy may not be dependent on mutational complexity. In this brief review, we discuss drugs that may emerge as important for the treatment of AML in the next 10 years.

Introduction

Promising novel agents evaluated over the past 40 years for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), with rare exceptions, have been relegated to the dustbin of history. Nevertheless, the revolution in understanding the genetics of AML facilitated by next-generation sequencing has led to many new investigational drugs against potential driver mutations such as mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) and Fms-related typrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) (Table 1). To date, a targeted agent is not available against DNMT3A mutations, which are thought to arise in the preleukemic hematopoietic stem cell population.1

Table 1.

Emerging and promising agents for the treatment of AML

| Agent | Mechanism of action | Suggested patient population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPX-351 | Liposomal formulation of 7+3 in 5:1 molar ratio | sAML fit for induction chemotherapy | Phase 2 study showed OS benefit in sAML |

| Phase 3 study fully accrued and waiting for final analysis | |||

| Vosaroxin | Novel topoisomerase II inhibitor | Relapsed/refractory AML | OS benefit when censored for allogeneic transplant; mucositis notable as toxicity |

| Guadecitabine | Hypomethylating agent resistant to deamination | Unfit for intensive chemotherapy | May supplant LDC, decitabine, 5-azacitadine |

| SGN-CD33A | ADC against CD33 with stable linker | Being explored as a combination with hypomethylating and traditional induction | Next-generation ADC against CD33 |

| Volasertib | Novel PLK1 inhibitor | Being explored as a combination with hypomethylating and traditional induction | OS benefit in small randomized phase 2 study when combined with LDC |

| Quizartinib | FLT3 inhibitor | FLT3 + AML | Impressive single-agent activity against FLT3-ITD; resistance emerges in most patients |

| Crenolanib | FLT3 inhibitor with activity against TKD-resistance mutation | FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD | Active against TKD mutations |

| ASP-2215 | FLT3 inhibitor with activity against TKD-resistance mutation | FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD | Impressive single-agent activity with CRc rate of 43% |

| AG-221 | IDH2 inhibitor | IDH2 mutated | Impressive single-agent activity (41% overall response rate) in relapsed or refractory AML |

| AG-120 | IDH1 inhibitor | IDH1 mutated | Impressive single-agent activity in relapsed or refractory AML |

| EPZ-5676 | DOT1L inhibitor | MLL rearranged | Combinations with standard of care should be explored |

| ABT-199 | BCL2 inhibitor | Ongoing investigation | May have increased activity in patients with IDH mutations |

| OTX-015 | BET inhibitor | Ongoing investigation | Combinations with standard of care should be explored |

| Pracinostat | HDAC inhibitor | Ongoing investigation | Impressive activity in combination with 5-azacitidine; awaiting survival data. |

7 + 3, 7 days of cytarabine and 3 days of daunorubicin.

The current outcomes for patients with AML are well known. Multiple international retrospective studies show that only 40% of patients younger than age 60 years survive more than 5 years.2 Indeed, even favorable-risk core-binding factor leukemias have an unacceptably high mortality rate of 56% at 10 years.3-5 Few patients who relapse after achieving a complete remission (CR) survive more than 5 years. Treatment approaches for patients unfit for traditional induction chemotherapy—hypomethylating agents or low-dose cytarabine (LDC)—are modestly effective but inadequate.6,7 It is estimated that 20 830 people will be diagnosed with AML in the United States in 2015, making AML a relatively rare malignancy. Because of this, AML is considered an orphan disease by the US Food and Drug Administration. Challenges in the development of drugs for AML are formidable and have recently been addressed.8

We present a mechanism-based overview of novel agents currently in clinical trials that have published data or have been presented at a major international meeting. In our opinion, these drugs may be used to treat AML, either alone or in combination with the current standard of care during the next 5 years. This review is not meant to be exhaustive. The landscape of targets is well known, and new drugs are introduced at a rapid pace. Rather, we focus on those agents that will likely pave the road to success.

Novel formulations of cytotoxic chemotherapy

Despite the excitement over new therapeutic agents against genetic and epigenetic targets, in the last 10 years improvements in overall survival (OS) have been driven by refinements in the use of conventional chemotherapy.9,10 With history as a guide, continued modifications and reformulations of traditional chemotherapy may incrementally improve OS.

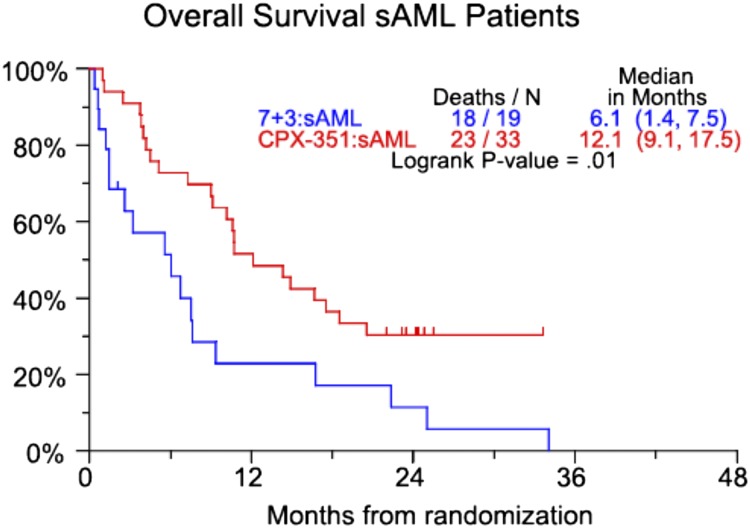

CPX-351

CP-351 is a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin in a 5:1 molar ratio. In vitro studies demonstrate that this ratio has the highest level of synergy and the lowest level of antagonism.11 In a randomized, open-label phase 2 trial, 127 patients age 60 to 75 years with or without secondary AML (sAML; defined as AML with a history of an antecedent hematologic disorder or therapy-related AML) were randomly assigned in a 2:1 fashion to induction chemotherapy with CPX-351 or daunorubicin (60 mg/m2) and cytarabine (100 mg/m2/d for 7 days). Patients who received CPX-351 for induction could receive CPX-351 for consolidation. Those patients who received daunorubicin and cytarabine during induction could receive cytarabine-based consolidation.12 Primary end points were the rate of CR and CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi). Secondary end points were event-free survival (EFS) and OS. The composite CR (CRc) rate (CR + CRi) was 66.7% for all patients treated with CPX-351 and 51.2% in the group receiving daunorubicin and cytarabine. The improved response rate in the CPX-351 group did not reach statistical significance (P = .07). There was neither an EFS nor OS benefit when all patients were considered. However, the higher rate of CRc in the CPX-351 group did lead to a statistically significant 6-month survival benefit in patients with sAML (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CPX-351 vs 7+3 (7 days of cytarabine and 3 days of daunorubicin). OS for patients with secondary AML. Numbers in parentheses represent confidence intervals. Reprinted from Ravandi et al12 with permission.

In a separate study, patients between the ages of 18 and 65 years with AML in first relapse were randomly assigned 2:1 to CPX-351 or investigator’s choice of salvage regimens. In the entire cohort, there was a trend toward increased CRc in the CPX-351 group but no difference in EFS or OS.13 In a subset analysis of poor-risk patients as defined by the European Prognostic Index (a prognostic index for adult patients with AML in first relapse), median OS was improved by 2.4 months in patients treated with CPX-351 although EFS was statistically similar.14

On the basis of these results, an open-label, randomized phase 3 study of CPX-351 vs daunorubicin (60 mg/m2)-cytarabine was initiated for sAML in patients between the ages of 60 and 75 years (NCT01696084). The trial is fully accrued and results are expected in late 2016.

If CPX-351 results in an OS benefit in the randomized phase 3 trial, it may become the preferred treatment for patients older than age 60 years with sAML. However, subgroup analysis of a phase 3 study demonstrated that daunorubicin 90 mg/m2 leads to an increased OS in AML patients age 60 to 65 years.15 It may be that CPX-351 is equivalent to daunorubicin 90 mg/m2 while being superior to daunorubicin 60 mg/m2. Furthermore, the phase 2 study that demonstrated an OS benefit with CPX-351 strictly defined sAML; only patients with a known history of an antecedent hematologic disorder or therapy-related AML were included. The current phase 3 study broadens the sAML definition to include patients with AML with myelodysplasia-related changes and AML with cytogenetic abnormalities characteristic of myelodysplastic syndrome. Dysplasia also occurs in patients with de novo AML, and myelodysplasia-related changes are in the eye of the pathologist. The group enrolled in the phase 3 study may be different from the group with an OS benefit in the randomized phase 2 trial. Despite these caveats, that phase 3 study offers a significant possibility of improving on the current standard of care for older adults who are eligible for induction chemotherapy.

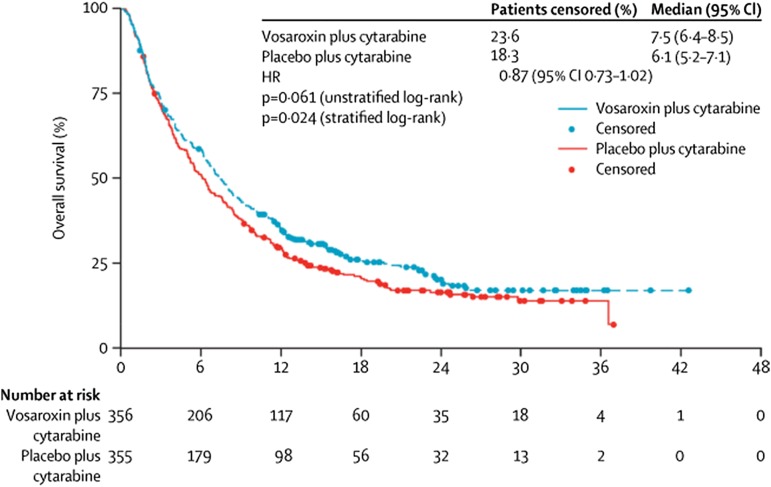

Vosaroxin

Daunorubicin is a critical component of standard induction chemotherapy, but it can cause cardiac toxicity, particularly in patients with preexisting heart failure. Vosaroxin is a quinolone derivative that inhibits topoisomerase II without the production of oxygen free radicals that lead to the cardiac toxicity observed with other topoisomerase II inhibitors. Based on encouraging early clinical data, a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 study of cytarabine (1 g/m2 days 1-5) with or without vosaroxin (90 mg/m2 days 1-4) was initiated for patients with primary refractory AML or AML in first relapse.16 Of the 711 patients enrolled on the study, the CR rate in the vosaroxin arm was 30.1%, nearly double the 16.3% rate seen in the placebo arm. Despite this, OS trended toward but did not meet statistical significance, with median OS of 7.5 months for cytarabine-vosaroxin compared with 6.1 months for cytarabine-placebo (P = .06) (Figure 2). After censoring at the time of allogeneic stem cell transplantation, patients who received vosaroxin had a statistically significant (P = .02) median OS benefit of 1.4 months (median OS, 6.7 months vs 5.3 months favoring vosaroxin). In a preplanned intention-to-treat analysis of patients older than age 60 years, median OS was 7.1 months vs 5.0 months favoring vosaroxin. Fifteen percent of patients on the vosaroxin arm developed grade 3 or 4 stomatitis that either interfered with oral intake or had life-threatening consequences.

Figure 2.

OS in VALOR trial (intention to treat population). HR, hazard ratio.

Two separate open-label randomized phase 2 trials, one of vosaroxin vs low-dose LDC and the other of vosaroxin with LDC vs LDC alone, led to no differences in CR rate or OS between the arms treated with vosaroxin and the arms treated with LDC alone.17 In addition, toxicity in patients treated with vosaroxin mirrored that seen in the phase 3 study, with gastrointestinal toxicity significantly more common in the patients treated with vosaroxin. However, the 30-day and 60-day mortality were similar in the 2 arms of the study.

The future of vosaroxin at the dose and schedule used in the phase 3 study is in doubt. Despite the OS benefit seen when patients were censored at the time of allogeneic transplantation, the clinical significance of a 6-week OS benefit is unclear. Nevertheless, vosaroxin has proven clinical activity, and future studies may clarify the best dose and schedule for optimizing that activity.18

Guadecitabine

Along with LDC, hypomethylating agents have emerged as the de facto treatment for patients with AML who are ineligible for conventional cytotoxic induction chemotherapy. The CR rate in randomized clinical trials of hypomethylating agents is no better than 30%, and median OS is similar to that of conventional care regimens.6,7 Guadecitabine (SGI-110) is a dinucleotide of decitabine and deoxyguanosine that increases the in vivo exposure of decitabine by protecting it from deamination. In a randomized study comparing guadecitabine at 60 mg/m2 to 90 mg/m2 in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML, there were no significant differences between groups in CR rate. In a combined analysis of 51 patients who received either dose of guadecitabine, the CRc was 57%, with 37% of patients achieving a true CR. This translated into a median OS of 10.5 months in the entire patient population and 18.2 months in those patients who achieved a CR.19 On the basis of these data, a large, randomized phase 3 study of guadecitabine vs 5-azacitidine, decitabine, or cytarabine has been initiated (NCT02348489).

If the randomized phase 3 study shows an OS benefit, guadecitabine may supplant hypomethylating agents as the agent of choice for patients with AML unfit for traditional induction chemotherapy. However, both decitabine and 5-azacitidine are now available as generic formulations, and there may be a substantial difference in cost between guadecitabine, decitabine, and 5-azacitidine. If guadecitabine shows a marginal OS benefit, its use may be restricted by payors.

Antibody-drug conjugates

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) against a variety of cell surface receptors on leukemic myeloblasts are in clinical development. CD33 is a transmembrane cell surface receptor expressed on cells with a myeloid lineage. Because of its presence on myeloblasts, targeting CD33 on the surface of leukemic blasts either with naked antibodies or ADCs is variably successful.20-22 The only example of a successful ADC to date is gemtuzumab ozagomicin, which received accelerated approval but was subsequently withdrawn from the market.23 Despite this, efforts to improve upon its dosing and schedule have led to clinical trials that suggest a survival benefit in certain subsets of patients treated with gemtuzumab ozagomicin.24,25

SGN-CD33A is a novel ADC with highly stable dipeptide linkers that enable uniform drug loading of a pyrrolobenzodiazapine dimer that crosslinks DNA leading to cell death. An interim analysis of a phase 1 dose-escalation study of SGN-CD33A in patients with relapsed CD33+ AML and those patients who declined intensive therapy, the CRc rate was 29%. Seventy-seven percent of patients who received doses of 40 μg/kg or higher had at least a 50% reduction in bone marrow blasts.26 There is an ongoing study of SGN-CD33A alone and in combination with hypomethylating agents.

All anti-CD33 ADCs induce myelosuppression; the term CR with incomplete platelet count recovery was coined as a direct result of the bone marrow blast clearance but ongoing thrombocytopenia seen in patients treated with gemtuzumab ozagomicin. SGN-CD33A appears to have the antileukemic activity of gemtuzumab ozagomicin without liver toxicity. In this way, it represents the pinnacle of an anti-CD33 ADC.

Molecularly targeted agents

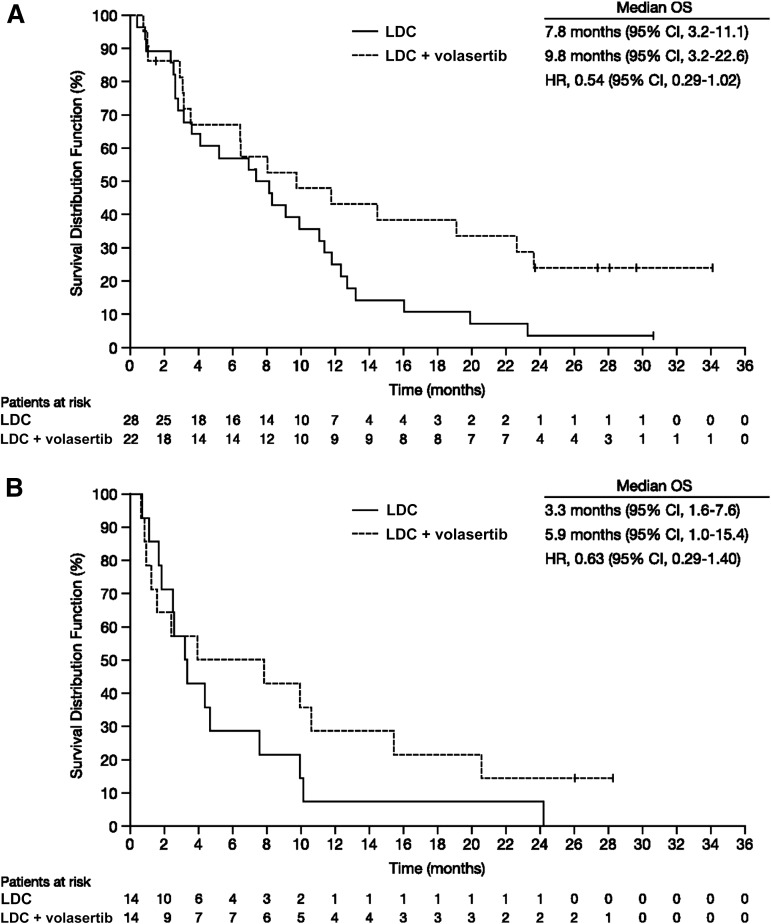

Volasertib inhibits polo-like kinase 1 (PLK10), PLK2, and PLK3. PLKs are a family of 5 conserved serine/threonine kinases that are important for checkpoint regulation and cell cycle progression. Inhibition of PLK1, which is overexpressed in human AML cells, leads to a disorganized spindle assembly and cellular apoptosis.

In a phase 2 study, 89 patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to volasertib with LDAC or LDAC alone.27 The dose of volasertib was 350 mg on days 1 and 15 of a 28-day cycle. CRc was 31% in the combination arm compared with 13.3% with LDAC monotherapy with a strong trend toward statistical significance (P = .052). Both EFS and OS were significantly longer in the combination arm; median OS was 8.0 months with volasertib with LDAC and 5.2 months with volasertib alone (Figure 3). Clinical trials of volasertib in combination with induction chemotherapy (NCT02198482) and decitabine (NCT02003573) are ongoing.

Figure 3.

OS estimates according to randomization and European Leukemia Net genetic group. (A) Favorable and intermediate I/II groups. Median OS times for patients who received LDC (n = 28) and LDC + volasertib (n = 22) were 7.8 and 9.8 months, respectively (HR, 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29-1.02). (B) Adverse group. Median OS times for patients who received LDC (n = 14) and LDC + volasertib (n = 14) were 3.3 and 5.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.29-1.40). Database snapshot November 7, 2013.

FLT3 inhibitors

Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is a type 3 receptor tyrosine kinase expressed on hematopoietic progenitors and on most leukemic myeloblasts. FLT3 internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITDs) are seen in approximately 30% of patients with de novo AML. Patients with FLT3-ITD have a poor prognosis.28,29 The development of FLT3 inhibitors is a priority. Despite a litany of first-generation FLT3 inhibitors—those that are approved for treatment of other malignancies (sorafenib and sunitinib) and unapproved drugs that have been explored in late-stage clinical trials (lestaurtinib and midostaurin)—the search continues for a novel durable inhibitor of FLT3 that leads to a durable OS benefit. However, there is considerable interest regarding 4 agents currently in clinical trials: midostaurin, quizartinib, crenolanib, and gilteritinib (ASP-2215).

Midostaurin

Midostaurin is an inhibitor of FLT3, c-KIT, PDGFRB, VEGFR-2, and protein kinase C. A phase 1B study explored different dose levels and schedules of midostaurin in combination with induction chemotherapy. The trial enrolled patients between the ages of 18 and 60 years, both FLT3 wild-type (FLT3-WT) and FLT3 mutant. In the cohort that received 50 mg twice per day (either sequentially or concomitant with chemotherapy), the CR rate was 92% in patients with FLT3-ITD or FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain (FLT3-TKD) and 74% in patients who were FLT3-WT.30 These encouraging results led to the development of the RATIFY study, an international, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of midostaurin (PKC412) in combination with daunorubicin (60 mg/m2 for 3 days) and cytarabine (200 mg/m2 for 7 days). For patients who achieve a CR, consolidation chemotherapy is continued with either midostaurin or placebo. In addition, maintenance therapy after consolidation is given with midostaurin or placebo. There is no crossover in treatment arms after patients achieve CR. The primary study outcome is OS, not censored at the time of allogeneic bone marrow transplant.31 The trial has been open since 2008, and results are eagerly awaited.

Quizartinib

Quizartinib (formerly known as AC220) was developed as a highly selective second-generation FLT3 inhibitor.32 In a phase 1 study of quizartinib in patients with relapsed or refractory AML, regardless of FLT3 mutation status, the maximum tolerated dose was 200 mg/d.33 A variety of phase 2 studies demonstrated the effectiveness of quizartinib in the relapsed and refractory settings (see Levis et al,34 Cortes et al,35 and Schiller et al36). What is notable about all of these studies (whether patients were in first relapse or later, young or old) is the relatively remarkable CRc rate, partial remission (PR) rate, and median duration of response. The CRc ranged between 44% and 54% whereas the overall response rate (CRc + PR) was between 61% and 72%. Of crucial importance, the PR definition did not require normalization of platelet and neutrophil counts as defined in the International Working Group Criteria. Median duration of response ranged between 11.3 and 12.7 weeks.

Despite the promising single-agent activity of quizartinib, 50% of patients relapsed within 3 months. Further studies suggest that the mechanism of resistance to quizartinib is acquired mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the FLT3 gene, including mutations in D835 and F691.37,38 Because of this, agents that overcome this resistance and lead to a longer duration of response are seen as crucial to the development of targeted inhibitors of mutant FLT3. Crenolanib is such an agent.

Crenolanib

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor crenolanib has activity against the D835 mutation found in the activation loop of FLT3. Crenolanib, as a pan selective FLT3 inhibitor overcomes quizartinib resistance. A phase 2 study of crenolanib in patients with relapsed or refractory AML and an FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD was presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2014.39 All patients received crenolanib at a dose of 200 mg 3 times per day, and patients were stratified on the basis of whether they had received prior FLT3-directed therapy (eg, quizartinib, midostaurin, sorafenib, or PLX3397).

Crenolanib induced a CRi in 23% of patients who were FLT3 inhibitor naïve but in only 5% of patients who had received prior FLT3 therapy. Both treatment groups had similar degrees of hematologic improvement (31% and 33%, respectively), although it is unclear whether this modest improvement translated into clinical benefit. Crenolanib is now being investigated in combination with induction chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed AML with an FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD mutation (NCT02283177).

Gilteritinib

Gilteritinib (ASP-2215) is a potent inhibitor of both FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD mutations. A phase 1/2 trial was initiated in 2013 in FLT3-WT and FLT3-mutant patients, and interim results were reported in 2015.40 A total of 166 patients were enrolled in a combination of dose-escalation and in-parallel dose-expansion cohorts. The maximum tolerated dose was 300 mg once per day. Of note, both FLT3-WT and FLT3-mutant patients were enrolled on the study. FLT3-WT patients derived minimal benefit from gilteritinib, with a CRc of 8% and a PR rate of 3%. In the FLT3-mutant patient population, the overall response rate was 57% with a CRc rate of 43% and a PR rate of 15%. A phase 1 study of gilteritinib in combination with induction consolidation chemotherapy is ongoing (NCT02236013), and a randomized phase 3 study of gilteritinib vs salvage chemotherapy is planned (NCT02421939).

The new generation of FLT3 inhibitors are remarkably active in patients with relapsed/refractory FLT3-positive AML. These inhibitors are able to clear blasts from the bone marrow, but they are less effective at restoring normal hematopoiesis. The rate of CRi and isolated blast decrease in the marrow is much higher than the rate of true CR. For example, in the initial results from gilteritinib, the true CR rate was only 5%. This may be because suppressing the FLT3 clone does not fully eradicate other clonal drivers of disease that contribute to leukemogenesis and abnormal hematopoiesis. In addition, the relatively short duration of response in patients receiving quizartinib and gilteritinib (mean duration of response, 126 days) makes both of these agents potentially ideal candidates to bridge patients to an allogeneic stem cell transplantation but are less likely to benefit older patients for whom allogeneic transplantation is not an option. For this reason, combining FLT3 inhibitors with other novel agents, induction chemotherapy, or hypomethylating agents may lead to improved CR and OS. The RATIFY study, when reported, should provide robust data about whether combining an FLT3 inhibitor with chemotherapy improves survival.

IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors

IDH2 (found in the mitochondria) and IDH1 (found in the cytoplasm) function in their WT state to catalyze the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate. IDH2 is mutated in 10% to 15% and IDH1 is mutated in 5% to 10% of adult AML.41-43 The prevalence of both IDH mutations appears to increase as patients age; IDH mutations are relatively rare in patients with pediatric AML.42,44 Mutations in IDH2 are enriched in patients with normal karyotypes, but up to 30% of patients with IDH2 mutations have abnormal cytogenetics at the time of diagnosis. These generally fall into the intermediate or unfavorable cytogenetic risk groups as defined by the European Leukemia Net classification. Mutant IDH enzymes acquire neomorphic activity and catalyze the conversion of α-ketoglutarate into β-hydroxyglutarate, increase levels of β-hydroxyglutarate, and cause hypermethylation of target genes leading to a block in myeloid differentiation (Figure 2).45-47 Inhibitors of mutant IDH1 and IDH2 are currently in phase 1 clinical trials (NCT02381886, NCT01915498, NCT02074839), and early results have demonstrated that these agents have encouraging efficacy in patients with relapsed disease. In phase 1 clinical trials, inhibitors of mutant IDH1 and IDH2 are remarkably active with minimal toxicity.

Interim results of a phase 1/2 study of AG-221 (Agios/Celgene), the first IDH2 inhibitor currently in clinical trials, were presented at the annual meeting of the European Hematology Association in 2015 and demonstrated an overall response rate of 41% in patients with relapsed/refractory AML.48 Twenty-seven percent of patients cleared their bone marrow of blasts with various levels of count recovery (true CR, CRi, and morphologic leukemia-free states), and 18% of patients achieved a true CR. An additional 14% of the patients had a true PR with normalization of platelet count and absolute neutrophil count. Seventy-six percent of the responding patients have been on treatment for at least 6 months. Interestingly, an additional 44% of patients had clinical stable disease defined as a stable or decreased blast percentage in the bone marrow that does not meet the criteria for PR. Some of these patients with stable disease are red cell transfusion independent, have normal platelet counts, and a normal absolute neutrophil count, despite persistence of blasts in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. The number of patients with clinically meaningful stable disease and those with smoldering AML is an area of active investigation because it has implications for the OS benefit that may be observed in these patients.

Inhibitors of mutant IDH1 in clinical development include AG-120 (Agios) and IDH305 (Novartis). Early results for AG-120 in patients with relapsed AML have shown evidence of efficacy similar to that of the IDH2 inhibitor, with an overall response rate of 31% and a true CR rate of 15%. An additional 27 patients had stable disease. Dose escalation continues, and expansion cohorts in patients with relapsed/refractory AML have been initiated.

DOT1L, BCL-2, BET bromodomain inhibitors, and histone deacetylase inhibitors

Other agents against molecular targets are in the midst of ongoing clinical trials. These include the DOT1L inhibitor EPZ-5676, the BCL2 inhibitor ABT-199, and inhibitors of bromodomain (BET) proteins.

The prognosis of patients with acute leukemia and a translocation or partial tandem duplication of the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene is poor. In a study of 1897 patients with AML treated within German AML Cooperative Group trials between 1992 and 1999, 2.8% of patients were found to have a rearrangement involving 11q23. OS at 3 years was 12.5%.49 Elegant in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that a key mediator of MLL-rearranged leukemia is the histone methyltransferase DOT1L.50-54 Similarly, preclinical studies of DOT1L inhibition in acute leukemia associated with translocations involving the MLL gene have shown remarkable effectiveness.55,56 Translating these results to patients has been more difficult. Inhibition of DOT1L with the small molecule inhibitor EPZ-5676 produced a CR in 2 of 34 patients with an MLL rearrangement or MLL-partial tandem duplication. In 1 patient, not only did morphologic evidence of myeloid disease disappear, but leukemia cutis resolved and the patient achieved a cytogenetic remission.57

The BCL2 inhibitor ABT-199 showed a CR/CRi in 5 of 32 patients, the majority of whom had relapsed or refractory disease. Interestingly, 3 of 11 patients with IDH mutation in the study were among the 5 patients achieving CR/CRi.58 Although there is preclinical data suggesting that IDH1 and IDH2 mutations induce BCL2 dependence in AML, the small numbers of responders in this early study makes any statement about the clinical effectiveness of BCL2 inhibition in IDH-mutant AML premature.59

Similar to the interest in DOT1L inhibition, small molecular inhibition of BET proteins has a robust preclinical rationale that is currently being tested in multiple clinical trials of AML (NCT02158858, NCT02308761, NCT01943851).60-62 To date, the only report from a clinical trial has been of the BET bromodomain inhibitor OTX-015.63 In that study, 36 patients with relapsed and refractory leukemia (33 with AML, 2 with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and 1 with myelodysplastic syndrome) were enrolled on this phase 1 dose-escalation study, and 28 were evaluable for dose-limiting toxicity. Of these, 1 patient had incomplete platelet count recovery and one patient had a true CR. Three other patients had evidence of clinical activity (decrease in blast percentage and resolution of gingival hypertrophy).

Finally, pracinostat is an orally available competitive inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC). In vitro studies show that it has >1000-fold selectivity for class I, II, and IV HDACs compared with class III HDACs with no effects on other zinc-binding enzymes. A phase 2 study of pracinostat in combination with 5-azacitidine in patients with previously untreated AML who are unfit for induction chemotherapy was completed in December 2014. The overall response rate was 54% (27 of 50 patients), and the CR rate was 42% (21 of 50 patients). Follow-up continues in an effort to calculate a median OS for the patients treated on study.

The results above speak to the difficulty of translating preclinical studies into therapeutically effective treatments in the clinic. The path forward for each of these drugs is either to identify a biomarker of response or to consider combining these agents with other drugs that are synergistic.

Incorporating emerging therapies into the treatment of AML

The new chemotherapies, hypomethylating agents, ADCs, and molecularly targeted agents all have clinical activity as single agents and may increase OS in patients with AML. However, it is likely that the best responses will be seen when these agents are combined with conventional induction chemotherapy or with each other. For example, one can envision a future in which it will be routine to combine FLT3 inhibitors and IDH inhibitors and perhaps even SGN-CD33A with induction chemotherapy and use molecularly targeted agents and ADCs in induction, consolidation, and as maintenance therapy after consolidation. We may use CPX-351 in patients with sAML, but clinical trials with CPX-351 in combination with molecularly targeted agents should also be explored. For patients with AML who are unfit for induction chemotherapy, a winner may emerge among volasertib, guadecitbine, and SGN-CD33A, but given their nonoverlapping mechanisms of action, we would encourage clinical trials that combine 1 or more of these agents and also combine them with molecularly targeted therapies. A decade from now, we believe the outcomes of patients with AML will improve because of these novel agents and other future drugs that build on their successes. Although drug development for AML may be a boulevard of broken dreams,64 as the comedienne Lily Tomlin noted, “The road to success is always under construction.”

Authorship

Contribution: E.S. and M.T. contributed equally to researching and writing this review article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.T. is on the Advisory Board for Agios Pharmaceuticals and has received research funding from Boehringer Ingleheim, Bioline, and Epizyme. E.S. is on the Advisory Boards for Agios Pharmaceuticals and Seattle Genetics and has received research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals and Seattle Genetics.

Correspondence: Eytan M. Stein, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Weill Cornell Medical College, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: steine@mskcc.org.

References

- 1.Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, et al. HALT Pan-Leukemia Gene Panel Consortium. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014;506(7488):328–333. doi: 10.1038/nature13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnett A, Wetzler M, Löwenberg B. Therapeutic advances in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):487–494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomfield CD, Lawrence D, Byrd JC, et al. Frequency of prolonged remission duration after high-dose cytarabine intensification in acute myeloid leukemia varies by cytogenetic subtype. Cancer Res. 1998;58(18):4173–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe JM. Important milestones in acute leukemia in 2013. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2013;26(3):241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appelbaum FR, Kopecky KJ, Tallman MS, et al. The clinical spectrum of adult acute myeloid leukaemia associated with core binding factor translocations. Br J Haematol. 2006;135(2):165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2670–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dombret H, Seymour JF, Butrym A, et al. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blasts. Blood. 2015;126(3):291–299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-621664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estey E, Levine RL, Löwenberg B. Current challenges in clinical development of “targeted therapies”: the case of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(16):2461–2466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-561373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Yao X, et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1249–1259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holowiecki J, Grosicki S, Giebel S, et al. Cladribine, but not fludarabine, added to daunorubicin and cytarabine during induction prolongs survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a multicenter, randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2441–2448. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer LD, Harasym TO, Tardi PG, et al. Ratiometric dosing of anticancer drug combinations: controlling drug ratios after systemic administration regulates therapeutic activity in tumor-bearing mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(7):1854–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancet JE, Cortes JE, Hogge DE, et al. Phase 2 trial of CPX-351, a fixed 5:1 molar ratio of cytarabine/daunorubicin, vs cytarabine/daunorubicin in older adults with untreated AML. Blood. 2014;123(21):3239–3246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-540971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortes JE, Goldberg SL, Feldman EJ, et al. Phase II, multicenter, randomized trial of CPX-351 (cytarabine:daunorubicin) liposome injection versus intensive salvage therapy in adults with first relapse AML. Cancer. 2015;121(2):234–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breems DA, Van Putten WL, Huijgens PC, et al. Prognostic index for adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1969–1978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löwenberg B, Ossenkoppele GJ, van Putten W, et al. Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hemato-Oncology (HOVON); German AML Study Group (AMLSG); Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) Collaborative Group. High-dose daunorubicin in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1235–1248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravandi F, Ritchie EK, Sayar H, et al. Vosaroxin plus cytarabine versus placebo plus cytarabine in patients with first relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia (VALOR): a randomised, controlled, double-blind, multinational, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis M, Russell N, Hills RK, et al. Vosaroxin and vosaroxin plus low-dose Ara-C (LDAC) vs low-dose Ara-C alone in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(19):2923–2932. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-608117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuart RK, Cripe LD, Maris MB, et al. REVEAL-1, a phase 2 dose regimen optimization study of vosaroxin in older poor-risk patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(6):796–805. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kropf P, Jabbour E, Yee K, et al. Late responses and overall survival (OS) from long term follow up of a randomized phase II study of SGI-110 (guadecitabine) 5-day regimen in elderly AML who are not eligible for intensive chemotherapy [abstract]. 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association; June 11-14, 2015; Vienna, Austria. Abstract P571; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenblat TL, McDevitt MR, Mulford DA, et al. Sequential cytarabine and alpha-particle immunotherapy with bismuth-213-lintuzumab (HuM195) for acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(21):5303–5311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekeres MA, Lancet JE, Wood BL, et al. Randomized phase IIb study of low-dose cytarabine and lintuzumab versus low-dose cytarabine and placebo in older adults with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):119–128. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldman EJ, Brandwein J, Stone R, et al. Phase III randomized multicenter study of a humanized anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody, lintuzumab, in combination with chemotherapy, versus chemotherapy alone in patients with refractory or first-relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4110–4116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersdorf SH, Kopecky KJ, Slovak M, et al. A phase 3 study of gemtuzumab ozogamicin during induction and postconsolidation therapy in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(24):4854–4860. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-466706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hills RK, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy improves survival in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(32):3924–3931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terré C, et al. Acute Leukemia French Association. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2012;379(9825):1508–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein EM, Stein A, Walter RB, et al. Interim Analysis of a Phase 1 Trial of SGN-CD33A in Patients with CD33-Positive Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21) Abstract 623. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Döhner H, Lübbert M, Fiedler W, et al. Randomized, phase 2 trial of low-dose cytarabine with or without volasertib in AML patients not suitable for induction therapy. Blood. 2014;124(9):1426–1433. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-560557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, et al. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2001;98(6):1752–1759. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fröhling S, Schlenk RF, Breitruck J, et al. AML Study Group Ulm. Acute myeloid leukemia. Prognostic significance of activating FLT3 mutations in younger adults (16 to 60 years) with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: a study of the AML Study Group Ulm. Blood. 2002;100(13):4372–4380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone RM, Fischer T, Paquette R, et al. Phase IB study of the FLT3 kinase inhibitor midostaurin with chemotherapy in younger newly diagnosed adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(9):2061–2068. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone RM, Dohner H, Ehninger M, et al. CALGB 10603 (RATIFY): A randomized phase III study of induction (daunorubicin/cytarabine) and consolidation (high-dose cytarabine) chemotherapy combined with midostaurin or placebo in treatment-naive patients with FLT3 mutated AML [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29. Abstract TPS199.

- 32.Zarrinkar PP, Gunawardane RN, Cramer MD, et al. AC220 is a uniquely potent and selective inhibitor of FLT3 for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood. 2009;114(14):2984–2992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Foran JM, et al. Phase I study of quizartinib administered daily to patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia irrespective of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication status. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3681–3687. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levis MJ, Perl AE, Dombret H, et al. Final Results of a Phase 2 Open-Label, Monotherapy Efficacy and Safety Study of Quizartinib (AC220) in Patients with FLT3-ITD Positive or Negative Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia After Second-Line Chemotherapy or Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation [abstract]. Blood. 2012;120(21). Abstract 673. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cortes JE, Perl AE, Dombret H, et al. Final Results of a Phase 2 Open-Label, Monotherapy Efficacy and Safety Study of Quizartinib (AC220) in Patients ≥ 60 Years of Age with FLT3 ITD Positive or Negative Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2012;120(21). Abstract 48. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiller GJ, Tallman MS, Goldberg SL, et al. Final results of a randomized phase 2 study showing the clinical benefit of quizartinib (AC220) in patients with FLT3-ITD positive relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5s). Abstract 7100.

- 37.Alvarado Y, Kantarjian HM, Luthra R, et al. Treatment with FLT3 inhibitor in patients with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia is associated with development of secondary FLT3-tyrosine kinase domain mutations. Cancer. 2014;120(14):2142–2149. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albers C, Leischner H, Verbeek M, et al. The secondary FLT3-ITD F691L mutation induces resistance to AC220 in FLT3-ITD+ AML but retains in vitro sensitivity to PKC412 and Sunitinib. Leukemia. 2013;27(6):1416–1418. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randhawa JK, Kantarjian HM, Borthakur G, et al. Results of a Phase II Study of Crenolanib in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients (Pts) with Activating FLT3 Mutations [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 389. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levis MJ, Perl AE, Altman JK, et al. Results of a first-in-human, phase I/II trial of ASP2215, a selective, potent inhibitor of FLT3/Axl in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2015 33. Abstract 7003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green CL, Evans CM, Zhao L, et al. The prognostic significance of IDH2 mutations in AML depends on the location of the mutation. Blood. 2011;118(2):409–412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(22):3636–3643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Wu YZ, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2348–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson AK, Miller DW, Lynch JA, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in pediatric acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward PS, Patel J, Wise DR, et al. The common feature of leukemia-associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(3):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;483(7390):474–478. doi: 10.1038/nature10860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiNardo C, Stein EM, Altman JK, et al. AG-221, an oral, selective, first-in-class, potent inhibitor of the IDH2 mutant enzyme, induced durable responses in a phase 1 study of IDH2 mutation-positive advanced hematologic malignancies. 2015.

- 49.Schoch C, Schnittger S, Klaus M, Kern W, Hiddemann W, Haferlach T. AML with 11q23/MLL abnormalities as defined by the WHO classification: incidence, partner chromosomes, FAB subtype, age distribution, and prognostic impact in an unselected series of 1897 cytogenetically analyzed AML cases. Blood. 2003;102(7):2395–2402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernt KM, Zhu N, Sinha AU, et al. MLL-rearranged leukemia is dependent on aberrant H3K79 methylation by DOT1L. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(1):66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deshpande AJ, Chen L, Fazio M, et al. Leukemic transformation by the MLL-AF6 fusion oncogene requires the H3K79 methyltransferase Dot1l. Blood. 2013;121(13):2533–2541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-465120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen L, Deshpande AJ, Banka D, et al. Abrogation of MLL-AF10 and CALM-AF10-mediated transformation through genetic inactivation or pharmacological inhibition of the H3K79 methyltransferase Dot1l. Leukemia. 2013;27(4):813–822. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen CW, Koche RP, Sinha AU, et al. DOT1L inhibits SIRT1-mediated epigenetic silencing to maintain leukemic gene expression in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Nat Med. 2015;21(4):335–343. doi: 10.1038/nm.3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kühn MW, Hadler MJ, Daigle SR, et al. MLL partial tandem duplication leukemia cells are sensitive to small molecule DOT1L inhibition. Haematologica. 2015;100(5):e190–e193. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, et al. Selective killing of mixed lineage leukemia cells by a potent small-molecule DOT1L inhibitor. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, et al. Potent inhibition of DOT1L as treatment of MLL-fusion leukemia. Blood. 2013;122(6):1017–1025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stein EM, Garcia-Manero G, Rizzieri DA, et al. The DOT1L Inhibitor EPZ-5676: Safety and Activity in Relapsed/Refractory Patients with MLL-Rearranged Leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 387. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Konopleva M, Pollyea DA, Potluri J, et al. A Phase 2 Study of ABT-199 (GDC-0199) in Patients with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML) [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 118. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan SM, Thomas D, Corces-Zimmerman MR, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations induce BCL-2 dependence in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2015;21(2):178–184. doi: 10.1038/nm.3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuber J, Shi J, Wang E, et al. RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478(7370):524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blobel GA, Kalota A, Sanchez PV, Carroll M. Short hairpin RNA screen reveals bromodomain proteins as novel targets in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(3):287–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dawson MA, Prinjha RK, Dittmann A, et al. Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478(7370):529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dombret H, Preudhomme C, Berthon C, et al. A Phase 1 Study of the BET-Bromodomain Inhibitor OTX015 in Patients with Advanced Acute Leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 117. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sekeres MA, Steensma DP. Boulevard of broken dreams: drug approval for older adults with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(33):4061–4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]