A recurrent arginine to histidine missense mutation in either the IDH1 or IDH2 genes (at codons R132 and R172, respectively) is present in >80% of lower grade (WHO II-III) diffuse gliomas and secondary glioblastomas arising within the cerebral hemispheres in adult patients [1]. In contrast, IDH1/2 mutations are not found in most pediatric counterparts, where a different set of genetic alterations have been identified including MYB or MYBL1 rearrangement, FGFR1 alterations, BRAFV-600E mutation, and mutations in the histone H3 variants H3F3A or HIST1H3B [4, 5]. The earliest age at which IDH1/2 mutation contributes to gliomagenesis is unknown but was previously thought to be during mid to late teenage years, as diffuse gliomas in older teenagers sometimes harbor IDH1/2 mutation, whereas diffuse gliomas in children and younger teenagers are virtually always IDH1/2 wildtype [2, 3]. Here we report three children under 10 years of age with diffuse gliomas harboring IDH1 mutation, suggesting that such mutations can also be oncogenic drivers in this age group, and therefore, that IDH testing is warranted in diffuse gliomas from all patients regardless of age.

The first patient is a previously healthy, 9 year old boy who first presented with headaches, emesis, gait instability, and incontinence. Examination revealed facial nerve palsy, left arm weakness, and blindness of the right eye. Head imaging demonstrated a large enhancing mass within the right frontal lobe with extensive surrounding FLAIR hyperintensity extending into the right basal ganglia, midbrain, and across the corpus callosum (Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. 1). He initially underwent decompressive craniotomy and subtotal resection followed by additional resection of the residual enhancing portion of the tumor two weeks later. Pathology demonstrated giant cell glioblastoma (WHO grade IV), characterized by numerous multinucleated and bizarre tumor cells, extensive infiltrative growth, high mitotic index, palisading necrosis, and microvascular proliferation. The tumor cells were immunopositive for IDH1-R132H mutant protein, had strong nuclear p53 immunoreactivity, and showed loss of ATRX expression. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed disomy 10 and polysomy 7 without EGFR amplification. Sequencing of H3F3A codon 34 and BRAF exon 15 were wild-type. Postoperatively, the patient underwent radiation with concurrent vorinostat therapy, followed by adjuvant lomustine and bevacizumab. Follow-up imaging at 10 months post-resection demonstrated tumor progression, and therapy was switched to everolimus. He died of progressive disease 13 months after initial diagnosis.

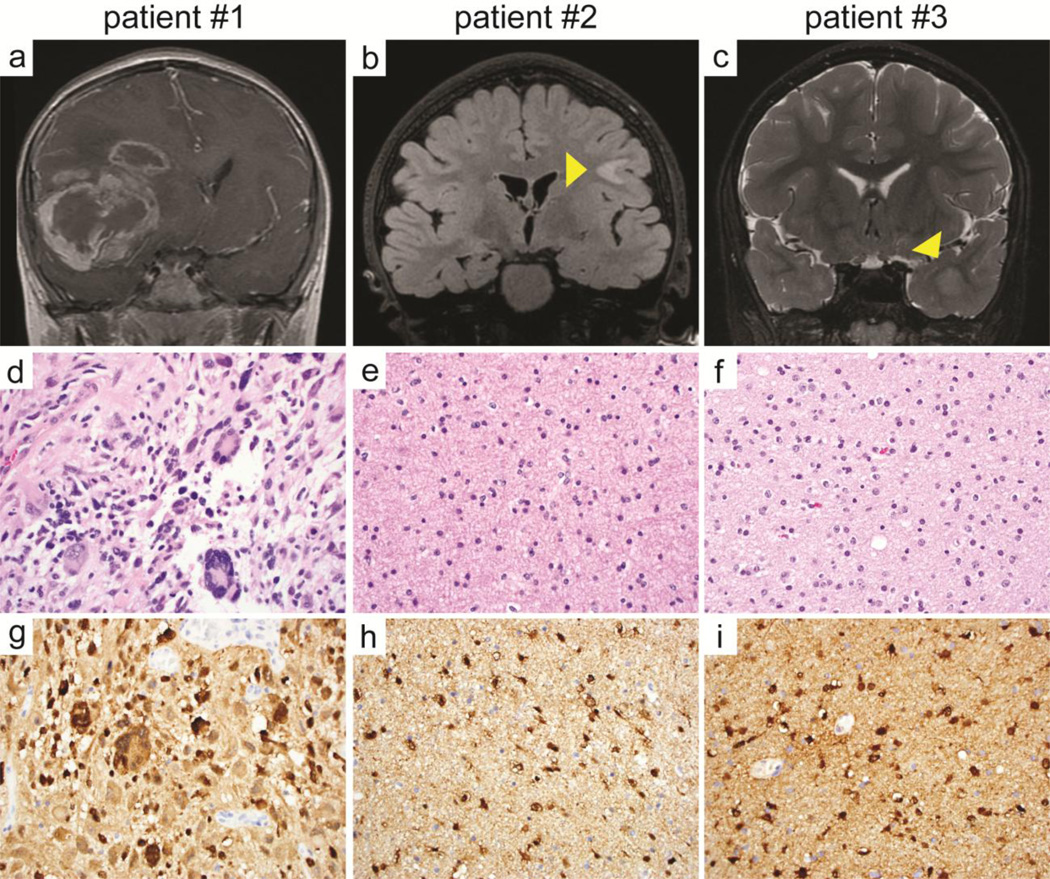

Figure 1.

Diffuse gliomas with IDH1 mutation in young children. a, b, c Coronal MR imaging from the three patients: T1-weighted post-gadolinium injection in patient #1 at 9 years of age (a), T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery in patient #2 at 9 years of age (b), and T2-weighted in patient #3 at 10 years of age (c). d, e, f H&E stained sections demonstrating giant cell glioblastoma in patient #1 and low-grade diffuse astrocytoma in patients #2 and #3. g, h, i Immunopositivity of the neoplastic astrocytes for IDH1-R132H mutant protein in the three tumors.

The second patient is a 9 year old girl with a history of autism spectrum disorder. Behavioral changes possibly due to headaches triggered neuroimaging. On head MRI, the patient was noted to have an area of mass-like FLAIR hyperintensity within the subcortical white matter of the left posterior frontal lobe (Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. 2). Review of imaging performed at 5 years of age revealed that this lesion had already been present and had expanded over the four year interval between MR imaging. Near total resection of the lesion was achieved with pathology demonstrating diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II), characterized by infiltrative glioma cells with irregular ovoid nuclei, coarse chromatin, and minimal cytoplasm without significant mitotic activity. The tumor cells were immunopositive for IDH1-R132H mutant protein and lacked p53 immunoreactivity. The patient did not receive adjuvant therapy and was monitored by serial MR imaging. Imaging at two years post-resection demonstrated increasing FLAIR hyperintensity adjacent to the prior resection cavity. She was subsequently enrolled on a phase 2 clinical trial (PNOC001) and received twelve cycles of everolimus. She exhibited disease progression while on everolimus and underwent repeat resection four years after her initial surgery. Pathology was consistent with a low-grade diffuse glioma with rounded nuclear morphology, initially suggestive of oligodendroglioma. The tumor cells were immunopositive for IDH1-R132H mutant protein, had intact ATRX expression, lacked p53 immunoreactivity, and had intact chromosomes 1p and 19q by FISH. Targeted next-generation sequencing revealed IDH1-R132H mutation and a TP53 frameshift mutation, molecularly consistent with a diffuse astrocytoma. Alterations in other known glioma genes including ATRX, TERT promoter, CIC, H3F3A, HIST1H3B, SETD2, MYB, MYBL1, and BRAF were not identified. She is currently receiving adjuvant radiation therapy and showed no new areas of disease on most recent imaging at three months after the second resection.

The third patient is an otherwise healthy boy who underwent a brain MRI at 8 years of age for headaches that had been ongoing since early childhood. A small focus of T2/FLAIR hyperintensity was noted within the anterior left temporal lobe (Fig. 1, Supplemental Figure 3). Serial imaging over the next four years demonstrated expansion into a space-occupying lesion. Subtotal resection was performed at 12 years of age with pathology demonstrating diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II), characterized by infiltrative glioma cells with irregular ovoid nuclei with coarse chromatin and minimal cytoplasm without significant mitotic activity. The patient underwent repeat surgery one month later and a gross total resection was achieved. The tumor cells were immunopositive for IDH1-R132H mutant protein, had intact ATRX expression, had strong nuclear p53 immunoreactivity within a subset of cells, and had intact chromosomes 1p and 19q by FISH. Targeted next-generation sequencing revealed IDH1-R132H and TP53-R273C missense mutations. Alterations in other known glioma genes including ATRX, TERT promoter, H3F3A, HIST1H3B, SETD2, MYB, MYBL1, and BRAF were not identified. This patient continues to be followed with close surveillance imaging at two months post-resection.

Together, these three patients demonstrate that IDH1 mutation is a pathogenic driver within a subset of gliomas arising in the cerebral hemispheres of young pediatric patients under 10 years of age. The pathology of these tumors ranged from low-grade diffuse astrocytoma to giant cell glioblastoma. Interestingly, the low-grade tumors in the second and third patients had intact ATRX expression and lacked mutations in ATRX or TERT promoter, suggesting that some of these IDH-mutant diffuse gliomas in children may be molecularly distinct from diffuse gliomas in adults. The significance of IDH1 mutation on the clinical behavior of gliomas in young children remains an open question, but these cases demonstrate that IDH1 mutant gliomas may be seen in children as young as five years of age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.N.K. is supported by NIH T32 grant (CA128583) and UCSF-CTSI Strategic Opportunities Support Program (A119683). S.M. is supported by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through UCSF-CTSI (KL2TR000143). D.A.S. is supported by NIH Director’s Early Independence Award (DP5 OD021403) and Career Development Award from the UCSF Brain Tumor SPORE (P50 CA097257).

References

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2481–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korshunov A, Ryzhova M, Hovestadt V, et al. Integrated analysis of pediatric glioblastoma reveals a subset of biologically favorable tumors with associated molecular prognostic markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:669–678. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Sobol RW, et al. IDH1 mutations are common in malignant gliomas arising in adolescents: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27:87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1264-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, et al. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:444–450. doi: 10.1038/ng.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:602–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.