Abstract

The median life expectancy following a diagnosis of glioblastoma (GBM) is 15 months. While chemotherapeutics may someday cure GBM by killing the highly dispersive malignant cells, the most important contribution that clinicians can currently offer to improve survival is by maximizing the extent of resection and providing concurrent chemo-radiation, which has become standard. Strides have been made in this area with the advent and implementation of methods of improved intraoperative tumor visualization. One of these techniques, optical fluorescent imaging with targeted molecular imaging agents, allows the surgeon to view fluorescently labeled tumor tissue during surgery with the use of special microscopy – thereby highlighting where to resect, and indicating when tumor-free margins have been obtained. This advantage is especially important at the difficult to observe margins where tumor cells infiltrate normal tissue. Targeted fluorescent agents also may be valuable for identifying tumor versus non-tumor tissue. In this review, we briefly summarize non-targeted fluorescent tumor imaging agents before discussing several novel targeted fluorescent agents being developed for glioma imaging in the context of fluorescent guided surgery or live molecular navigation. Many of these agents are currently undergoing preclinical testing. As the agents become available, however, it is necessary to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Keywords: Optical Imaging, Molecular imaging, Cancer Imaging, Glioma, Fluorescent-guided resection, Protein tyrosine phosphatase mu

Introduction

For patients with glioblastoma (GBM), greater extent of resection (EOR) is associated with improved overall survival.1-4 A probabilistic survival model developed to calculate personalized survival curves for patients with GBM, known as personalized survival modeling, suggests that maximal safe resection of malignant tissue yields significant survival benefits when considered along-side other patient-specific variables.5 This approach suggests that any degree of surgical resection is justified even in cases in which high EOR is thought preoperatively to be unachievable.5 In addition to longer overall survival, improving EOR may also improve tolerance and response to subsequent chemo- and radiation therapy.5, 6

The challenge to attaining maximal EOR in non-eloquent areas is the difficulty in discriminating the infiltrative glioma cells from disease-free brain. The standard of care, intraoperative white light reflectance microscopy with stereotactic guidance, often is incapable of discerning the exact location of these infiltrative and destructive cells. For example, optical imaging with white light reflectance alone is only 66% sensitive and 68% specific for glioma cells.7 The use of intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and intraoperative ultrasound improve visualization of glioma tissue, yet also exhibit inherent limitations: intraoperative MRI is expensive and time-consuming, whereas concerns exist as to the quality of intraoperative ultrasound images.1 Pre-clinical studies suggest that confocal laser endomicroscopy or “optical biopsy” with fluorescent dyes produces excellent histomorphologic images, which could be used by neuropathologists to aid in the imaging of glioma.8 This technology, however, is expensive, not widely available, and not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Finally, although all of these technologies improve the surgeons’ ability to resect tumors, they are non-specific and do not precisely label tumors and their margins.9

Fluorescent guided surgery (FGS)

FGS or live molecular navigation with targeted molecular imaging agents increases the specificity of tumor identification and is feasible to use in the operating suite.1, 9, 10 Surgical microscopes equipped with fluorescent filter kits use epi-fluorescence imaging to obtain tumor contrast: incident light of a specific wavelength excites fluorophores on the surface of tissues, which then emit light that is reflected back through the objective to the surgeon.11 To further improve upon the differentiation of tumor versus non-tumor tissue, multiple molecular tumor targeted imaging agents may be used simultaneously. The simplicity of adding this technology to the current work flow makes FGS with epi-fluorescence imaging and molecular imaging agents ideal for quickly improving EOR; nonetheless, this technology is limited by the depth of penetration of light and by light scattering of the tissue.11

In this review, we discuss targeted fluorescent molecular imaging agents that can be used with wide-field epi-fluorescent surgical microscopes for visualizing GBM and improving EOR. Excellent recent reviews have covered non-targeted fluorescent agents and nanoparticles used in glioma surgery or targeted molecular agents used in other types of cancer9-14 as well as fluorescent imaging agents in the context of spine surgery15 and will not be covered here.

Methodology

We searched PubMed for articles published in English with search terms “fluorescent,” “molecular,” “targeted,” “cancer,” “glioma,” “brain cancer,” “imaging,” in various combinations. Preclinical and clinical studies regarding malignant glioma or GBM optical imaging focusing on fluorescence were selected for further review. Positron emission tomography, MRI and studies that used other imaging modalities were excluded. On the basis of findings from these searches, more refined searches were done for 11 molecular imaging agents, using terms “fluorescein,” “ICG,” “5-ALA,” “EGFR,” “Den-Angio,” “angiopep-2,” “BLZ-100,” “chlorotoxin,” “tumor paint,” “SBK peptide,” “cathepsin,” “GB119,” “integrin alpha v beta 3,” “IRDye 800CW,” “CLR1502,” alone and in combination with the search terms “glioma,” “tumor,” and “imaging.” Studies cited in the reference sections of articles were also examined. The last PubMed searches were conducted in October 2015.

Optical imaging considerations

Ideal molecular imaging agents would have a high tumor specificity while not altering the current surgical flow.16 The primary limitation of fluorescent agents is their limited depth of penetration. This can be improved by using fluorophores in the far-red to near-infrared range (NIR; with an absorption coefficient of approximately 650-900 nm and an emission spectrum in the range of 800-1000 nm). The use of NIR agents avoids interfering with light absorption by hemoglobin (which absorbs light in the visible spectrum of 600 nm or less), and water and lipids (which absorb light in the infrared spectrum of greater than 900 nm).1, 17, 18 NIR agents in the window of 750-900 nM are best at minimizing autofluorescence.19 Ideally, a Stokes shift of 40 nM or greater prevents backscattering of excitation light thereby reducing autofluorescence.19, 20 These properties of NIR agents ensure a high tumor to normal ratio (TNR),18, 21 producing a signal 4 orders of magnitude stronger in NIR than in the visible range of the spectrum.17 The detection depth of the fluorescent signal for intraoperative fluorescence imaging is limited to only a few millimeters,17 but the use of multi-model imaging with MRI and/or positron emission tomography could help to overcome this inherent limitation of the fluorescent signal.9, 22, 23 Although the evaluation of the TNR and the ability to label tumor margin is critical for the development of targeted molecular imaging agents, other factors, such as pharmacokinetics, ease of use, and the ability to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) also must be considered for each agent.21

Non-targeted fluorescent imaging agents

Significant advances in glioma detection and surgical resection have been demonstrated with the non-targeted fluorescent agents fluorescein sodium, indocyanine green (ICG), and 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA). Fluorescein sodium and ICG penetrate glioma tissue via the enhanced permeability and retention effect, which refers to the tendency of macromolecules with an approximate size of 40-800 kDa or nanoparticles with hydrodynamic radii ranging from 7-100 nM to pass through leaky vasculature into tumor tissue, where they are retained due to compromised lymphatic drainage.24, 25 Retention of macromolecules in the tumor microenvironment can last for days to weeks.25, 26

5-ALA

Approved for use in high-grade glioma surgery in Europe, Japan and Canada,27 5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) is a hemoglobin precursor that is naturally converted into fluorescent porphyrins (PpIX) in the heme synthesis cycle in all mammalian cells.14 5-ALA is administered orally to patients approximately 3 hours before surgery.28 PpIX has an excitation wavelength of 400–410 nm and an emission wavelength of 634-705 nm. Emission at this wavelength yields pink fluorescence. PpIX accumulates preferentially in epithelial and malignant cells, including those of high-grade glioma,14, 29 as the result of differences in hemoglobin biosynthesis in these cells versus normal tissue.30 5-ALA has 92% positive predictive value, 77% specificity and 79% negative predictive value in high grade glioma with strong fluorescence.7

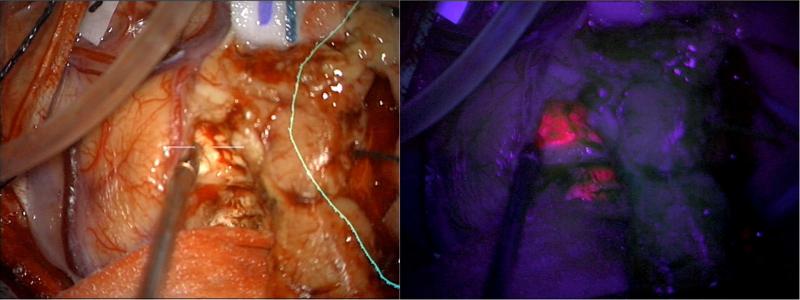

Figure 1 shows the use of 5-ALA for the visualization of human GBM tumor tissue during neurosurgical resection compared to white light. In a phase 3 clinical trial conducted in Germany in which the authors used 5-ALA for fluorescence guided surgical resection of malignant glioma, complete glioma resection was achieved in 65% of patients, versus only 36% with white-light alone.31 6-month progression free survival was significantly greater in patients given 5-ALA than those treated with white light alone.31 Similar findings have been observed in U.S clinical trials,32 validating the hypothesis that better delineation of tumor tissue supports better tumor resection and survival outcomes. Phase 2 clinical trials also demonstrated a benefit in the use of 5-ALA during recurrent tumor treatment, even in patients previously treated with radio- and chemotherapy.33, 34 Others have found that PpIX fluorescence may exceed the location of tumor tissue, resulting in false positives in 5-ALA guided surgical resection of recurrent malignant glioma, although surgical resection was still found to improve gross total resection, survival outcomes, or at worst not result in any additional neurological deficits in patients.35-37 False positive labeling in recurrent glioma patients is likely the result of PpIX fluorescence in areas of reactive astrocytes and macrophages,37 coagulation necrosis and vascular hyalinization.36 False positive PpIX fluorescence also may be related to how recently patients received radiation therapy.36

Figure 1.

5-ALA permits visualization of human GBM tumor tissue during neurosurgical resection. 5-ALA labeling of tumors is compared with white light during neurosurgery. Under white light (left panel), it appears through the operative microscope that the tumor has been completely removed from the region just with right of the suction device. The border of the tumor as it appears on MRI is demarcated with a yellow line. After turning on the blue light (right panel), the same view through the microscope demonstrates residual tumor (bright pink) despite its normal appearance under white light.

Despite showing promise in improvement of glioma resection, however, 5-ALA does have some limitations. First, PpIX displays limited fluorescence at tumor margins,12 and does not identify all the infiltrative cells at invasive tumor margins.7, 38, 39 Postoperative radiographic analysis has shown that on complete resection of tissue that fluoresces intraoperatively, postoperative/intraoperative MRI may continue to show abnormal areas of gadolinium enhancement consistent with tumor remnants.40 A recent phase 2 clinical trial demonstrates that more than 60% of non-PpIX fluorescent biopsy tissue had tumor cells present, with a 37.7% negative predictive value.33 In addition, limitations with current imaging systems may result in a failure to detect the labeling agent in weakly fluorescent PpIX positive infiltrative cells.41

Besides the false positive labeling mentioned previously in cases of recurrent malignant glioma resection, PpIX also can result in false positive labeling by leaking into extracellular fluid, edematous white matter tracts,7 and by labeling necrotizing vasculitis.28 5-ALA is not currently approved by the FDA and until recently has only been available in a small number of U.S. sites holding Investigational New Drug applications for this agent. XPharma Gen recently has obtained rights from Photonamic Gmb & H (Wedel, Germany) to market 5-ALA in the United States and is proposing a trial to gain approval by the FDA.

Fluorescein sodium

Fluorescein sodium is approved by the FDA, inexpensive, and used widely for retinal angiography.42, 43 This vascular flow agent non-specifically labels high-grade glioma tissue with an excitation wavelength of 460 to 500 nm and an emission wavelength of 540 to 690 nm.42 A YELLOW 560 fluorescent filter kit is available to use with a Pentero surgical microscope (Carl Zeiss Company, Oberkochen, Germany) to visualize fluorescein fluorescence during surgery.44 Acerbi et al.44 demonstrated that the YELLOW 560 filter improved visualization of both fluorescent and normal anatomy when in place.44 Fluorescein has 94% sensitivity and 89.5% specificity for glioma,43 and when used with a surgical microscope, gross total resection is achieved in 80% of patients, whereas the remaining patients had a range of percent of resection from 82-99.9% total.43 Another more recent study, however, found that fluorescein provided no benefit in the surgical resection of glioma.45 The authors of this more recent study closed their clinical trial using fluorescein in surgical resection of glioma due to the lack of correspondence between fluorescein and tumor tissue and the general high level of fluorescein fluorescence throughout the brain.45 This work emphasizes the neurosurgical need for specific, glioma-targeted imaging agents to molecularly identify malignant tissue.

ICG

ICG is used routinely for fluorescent imaging of blood vessels in angiography and is primarily used to monitor blood flow during neurosurgery46, 47 but also has been tested for use in glioma imaging.48 ICG fluoresces in the NIR range, with an excitation wavelength of 780 nm and emission wavelength of 800 nm. This improves its depth of penetration over the non-NIR agent, fluorescein. ICG is a non-specific agent that binds albumin in the blood and penetrates tumor tissue due to an increased vascular permeability.21 ICG highlights tumors within 30 minutes,21 and can identify tumor margins and guide surgical resection in rat glioma models.49,48 In patients with different types of brain tumors, delayed clearance was observed in tumor margins in the tumors of high grade glioma patients compared with low grade glioma and normal brain.48 ICG and fluorescein sodium are not used widely for tumor resection, however, because of the more widespread adoption of 5-ALA for glioma resection and because of their lack of tumor specificity.

Targeted fluorescent molecular imaging agents

The majority of clinical data for tumor imaging exists for the aforementioned non-targeted fluorescent agents. Most of the targeted fluorescent agents described in this section have not been used in the clinical setting or currently are being tested in clinical trials: consequently no human safety of EOR data are available. Additional considerations will also need to be considered on an agent-specific basis such as ease of administration, toxicity profile, delivery to target tissue, adequate labeling of the tumor margins, complications/side effects, and any change in EOR or outcomes as compared with controls.13

Molecular imaging agents identify and bind to target tissues by various mechanisms, and include metabolic targets, antibody-targeted, peptide or phospho-lipid-targeted, or enzymatic activity based probes. Many agents used for targeted glioma imaging use Cy5.5 or similar fluorophores in the near NIR to NIR range to optimize depth of penetration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Targeted Fluorescent Molecular Imaging Agents in Development for Glioma Surgery

| MI Agent | Mechanism of action or molecular target | Cell type targeted | Fluorophore and Max. Excitation/emission wavelengths (nM) | Tumor to Normal ratio +/− SEM | Preclinical study results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB119 | Cathepsin-L activatable54 | Glioma54 | Cy5 - 647/665 | N.D. | Improves EOR in animal model of glioma54 |

| Tumor Paint | Binds to MMP258, 59 and/or Annexin A260 | Glioma and other malignant tissue58 | Cy5.5 – 675/694 ICG – 780/80057 | Up to 3.3+/− 1.8 (ex vivo)62 | Clinical trials underway61 |

| Den-Angio (Angiopep-2) | Binds to Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)66 | GBM cells66 | Cy5.5 - 675/694 | 1.6+/−0.3 (in vivo)66 1.73 (ex vivo)69 | N.D. |

| EGFR targeting | Binds to EGFR79 | GBM cells79 | Cy5.5 – 675/69479; IRDye 800 CW - 774/80580 | 23.2+/−5.1 (intraoperative)80 | In mouse glioma model, significantly improves tumor resection80 |

| SBK agents | Binds to PTPμ fragments82 | GBM cells83 | Cy5 - 647/665 | N.D. | N.D. |

| PARP1 inhibitor | Inhibits Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1)87 | Nuclei of GBM cells87 | BODIPY- 503/512 | In excess of 10/1 (in vivo subcutaneous model)87 | N.D. |

| CLR1502 | Targets lipid rafts89 | GBM cells and glioma-like stem cells89 | 760/778 | 9.28+/−1.08 (ex vivo) 90 | N.D. |

| RGD | Binds to Integrin αvβ391, 96 | Mouse and human GBM cells96 | Cy5.5 -647/665 IRDye 800CW -774/805 | Maximum of 3.26+/− 0.18 (in vivo brain model)96; 4.24+/−0.92 (in vivo flank model)93 | Assisted in the ex vivo resection of mouse brain tumor model (RCAS-PDGF)96 |

Protease activatable agents

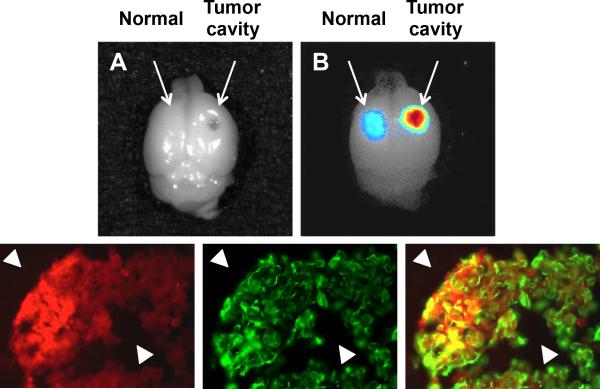

Cathepsin protease activatable agents are in development for tumor and glioma cell imaging.50 Cathepsin L and B are both upregulated in glioma cells.51, 52 A cathepsin-L specific cleavable activity based probe labeled with a NIR Cy5.5 fluorophore (excitation 675 nM, emission 694 nM), named GB119, has been developed to label glioma cells with increased cathepsin-L activity (Table 1). This agent specifically targets cathepsins and binds irreversibly to their active site, resulting in a bond rearrangement and release of the quenching sequence to yield a fluorescent signal.53 GB119 binding to cathepsin is highly enzyme specific (due to active site targeting) and stable (due to covalent bond formation).54 Topical application of GB119 labels glioma tumor cells in ex-vivo tumor models within 5 minutes of application and remains elevated for 35 minutes.54 Topical application of GB119 as opposed to systemic administration of the cathepsin B and L targeted agent, GB123, favors tumor margin labeling.54 Figure 2 shows the topical use of GB119 for labeling the main tumor mass and edges of gliomas. Application of GB119 in a mouse orthotopic brain tumor was used to identify residual glioma cells after resection.54 Cathepsin activatable probes also were used to image different solid tumors, and when used with the NIR Cy5.5 fluorophore, are able to label lung, colorectal and breast cancers in mouse models.55 To date, GB119 has not been tested in humans.

Figure 2.

Topical use of GB119 labels glioma tumors. Gross resection of a Gli36Δ5 tumor growing on the dorsal surface of the brain was performed and GB119 was added directly to the resulting cavity and imaged over time. (A) A monochromatic image of a whole brain showing the GB119 treated areas on the normal and tumor side (arrows). (B) An unmixed false colored map of pixel intensity representing activated GB119 within the cavity of the resected tumor shows activation of the probe is associated with the remaining tumor tissue but not with normal brain tissue (arrows). (B) Brains were sectioned through the dorsal cavity area and sections were analysed for GB119 activation and stained for vimentin. Sections demonstrating GB119-labeled tissue (false-colored red, left panel) are associated with vimentin-positive tumor xenograft (false-colored green, middle panel) but not with normal brain tissue (arrowheads). An overlay of the red and green signal is shown in the right panel (courtesy of James P. Basilion).

An advantage of proteolytic processing is the specific labeling of tumor tissue anywhere proteases are active, especially in sites of potential metastasis or as markers of sentinel lymph nodes. Fluctuation of enzymatic activity over time, however, is a limitation of activity based probes and may lead to inconsistent tumor labeling.

Peptide and phospholipid targeted molecular imaging agents

Peptide and phospholipid targeted probes recognize specific molecules outside of, on the surface of, or inside of cells. An ideal target would naturally accumulate in tumor tissue to biologically amplify the signal. Agents that show promise for surgical resection of glioma include Tumor Paint (Blaze Biosciences Inc., Seattle, Washington, USA), Angiopep- 2 targeting agents, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted agents, PTPμ-targeted SBK agents, the fluorescently labeled poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) inhibitor (CLR1502), and αvβ3 integrin-targeted agents.

Tumor Paint

Tumor Paint is composed of a scorpion toxin, chlorotoxin, linked to the NIR fluorophore, Cy5.5 (excitation 675 nM, emission 694 nM; Table 1) or ICG (excitation 780 nM, emission 800 nM).56, 57 Chlorotoxin binds to either MMP258, 59 or Annexin A260. Tumor Paint crosses the BBB to label glioma and labels a number of other cancer types with a significantly greater signal in tumor than in normal tissue.58 Tumor Paint can be used to image collections of cancer cells as small as a few hundred cells in size.58 To date, pre-clinical studies have not evaluated how well Tumor Paint labels tumor margins. Tumor Paint is administered intravenously, on the order of hours to days before surgery.58, 61 Monolabeled chlorotoxin with a single NIR moiety is less expensive to produce consistently for commercialization; more serum stable than mono-, di-, and tri-labeled mixtures of the original Tumor Paint; and maintains a serum half-life of 14 hours and a TNR of 3.3 +/− 1.8 for an alanine substituted version or 2.6 +/− 0.85 for an arginine substituted version.62 One of these mono-labeled substituted versions of Tumor Paint will be used in clinical trials.62 Blaze Biosciences Inc. currently is recruiting participants for a Phase 1 clinical trial of Tumor Paint's safety in glioma patients.61 Chlorotoxin also has been used as the targeting moiety in the development of various theranostics in preclinical studies.63

Angiopep-2 targeting agents

Angiopep-2 is a ligand of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), which is expressed by both endothelial and glioma cells. As such, Angiopep-2 is hypothesized to be an excellent candidate for molecularly targeting both endothelial and glioma cells. Angiopep-2 peptides are effective at transcytosing the BBB64 and targeting glioma cells.65 When linked to a dendrimer nanoparticle (any organic or inorganic particle only nanometers in size that can be conjugated to targeting and contrast agents) and Cy5.5 (excitation 675, emission 694 nM), Angiopep-2 (named Den-Angio) can cross the BBB and label glioma tissue in animal models (Table 1).66 Den-Angio is internalized by LRP receptor-mediated endocytosis.67 In histological studies, Den-Angio labels glioma tumor margins well,66, 67 with a TNR of 1.6 +/− 0.3.66 A proteolytically resistant steroisomer of Den-Angio, DAngio-pep is more serum stable, more efficient, and labels tissue for a significantly longer time than the L-isomer,68 making it a more attractive imaging agent for clinical testing. Another Angiopep-2 targeting agent, with Angiopep-2 anchored to carbonaceous nanoparticles, allows for NIR imaging and preferential targeting of orthotopic C6 glioma models, with a TNR of 1.73.69 Angiopep-2 has been linked to gadolinium for use with preoperative MRI and surgical planning,67 and to chemotherapeutic and phototherapeutic agents for brain tumor treatment.70-73 A combination of Angiopep-2 targeting with activating cell penetrating peptide (ACP) and the chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel generated a more potent chemotherapeutic than without the ACP fragment in a mouse orthotopic glioma model.74, 75 The large body of positive preclinical studies on Angiopep-2 to date, and the dual targeting mechanism of Angiopep-2, make it an excellent candidate as a theranostic for delivery of therapeutics and/or molecular imaging.

EGFR targeting agents

EGFR is overexpressed in approximately 90% of GBM cells and in more than 40% of patients.76 Therefore, it is also an excellent target both for glioma diagnostics and theranostics. A number of laboratories are working toward developing fluorescent molecular imaging agents targeting EGFR (Table 1). For example, colloidal gold nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol, epidermal growth factor (EGF) peptides, and phthalocyanine 4, a photodynamic therapy agent, were generated to target glioma cells.77 The EGF colloidal gold nanoparticles effectively target mouse brain tumor models within 4 hours of injection, and are excreted from the body quickly, suggesting they may be safe for use in humans.78

A different labeling agent, this time using EGF targeting peptides, EGFPEP, conjugated to NIR Cy5.5 labels GBM cells in culture, orthotopic brain tumors ex vivo, and orthotopic brain tumors in vivo, within 1 hour of injection.79 The average signal of fluorescence intensity using the EGFPEP agent was significantly greater in brain tumors of the human glioma cell line that overexpresses EGFR, Gli36Δ36, than in the brain tumors of a non-EGFR overexpressing cell line, U-87 MG.79 By using an anti-EGFR antibody, Cetuximab, linked to the NIR fluorophore, IRDye 800 CW (excitation 774 nM, emission 805 nM), Warram et al. achieved an intraoperative TNR of 23.2+/− 5.1, and significantly improved tumor resection compared to white light alone in a mouse orthotopic model of malignant glioma.80 IRDye 800 CW has been shown to be superior to Cy5.5 as its signal penetrates tissues deeper and can produce a greater signal to background ratio.81 When considered alongside the fact that EGFR is one of the most commonly identified glioma oncogenes, these preclinical findings support the development of EGFR targeted molecular imaging agents.

PTPμ-targeted agents

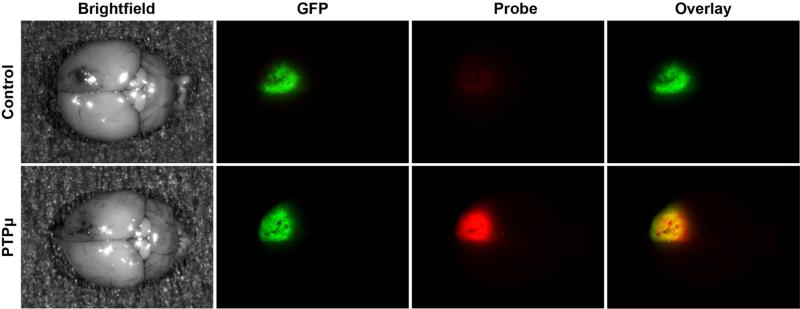

A series of peptides (SBK1-4) recognize a protein fragment of a receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTPμ, that accumulates exclusively in cancer cells and not in normal tissue (Table 1).82 These agents have been linked to several fluorophores including Texas Red, Cy5 and Alexa 750.82, 83 SBK2 and SBK4 can be administered intravenously immediately before imaging, cross the BBB to label intracranial tumors, and are stable for hours.83 SBK2 labels up to 99% of all tumor cells including the main tumor mass of an intracranial animal model of glioma (Figure 3) as well as tumor cells at the margin.83 Furthermore, in pre-clinical studies, SBK2 labels the margin even better than the main tumor mass and identifies dispersing cells up to 4 mm away from the main tumor mass when evaluated in 3-D reconstructions of mouse brains.83 SBK2 peptide conjugated to gadolinium specifically labels tumors within 5 minutes.84 The TNR measured in vivo for a flank tumor model for the gadolinium conjugated SBK2 probe is greater than with ProHance alone (~2:1).84 A quantitative MRI study recently conducted demonstrates a sustained binding of SBK2 to tumors over time compared with conventional contrast agents with an approximate 2:1 TNR 45-60 minutes after injection.85 Toxicity, dosage, and efficacy of the PTPμ-directed agents still needs to be tested in humans, but these preliminary studies are encouraging, especially considering the high level of tumor margin labeling. Human studies are being planned.

Figure 3.

PTPμ SBK2 peptide labels CNS-1 intracranial tumors in vivo. Cy5-conjugated SBK2 peptides were administered intravenously to mice with xenograft intracranial tumors of GFP-positive CNS-1 cells. Brightfield images of brains containing CNS-1-GFP tumors are shown on the left after tail vein injection of the peptides (Brightfield). GFP fluorescence of the brains indicates the location of the GFP-positive tumors cells CNS-1 (GFP). Cy5 images of the control or PTPμ probe fluorescence in the brains are shown (Probe). The overlay image of the GFP and Cy5 fluorescence is shown on the far right (Overlay). Scrambled control peptide did not label the tumors (Control, Probe). The SBK2 peptide (PTPμ) was able to cross the compromised blood-brain barrier to bind CNS-1 tumors, and overlapped with the GFP positive CNS-1 cells to create a yellow signal in the Overlay column.

PARP1 inhibitor

The DNA repair enzyme, PARP-1, is expressed in the nuclei of GBM tissue but not normal brain tissue.86 Tumor cells are sensitive to small molecule PARP-1 inhibitors, probably because of the fact that tumor cells often have defects in other DNA repair proteins. By adding a BODIPY fluorescent tag (excitation 503 nM, emission 512 nM) to a PARP-1 small molecule inhibitor (PARPi-FL), Irwin et al. generated a fluorescent molecular imaging agent for use in GBM (Table 1).87 This agent is metabolically stable in human serum and in mice, and has significantly greater uptake in orthotopic brain tumors than in muscle.87 In the orthotopic tumor bearing mice, PARPi-FL fluorescence is nuclear and is histologically confirmed to correspond to areas of tumor tissue.87 The use of the BODIPY-FL fluorophore, however, limits both the depth of penetration and the theoretical limit of the TNR for this agent. Use of a NIR fluorophore will likely increase the utility of this targeted molecular imaging agent for FGS.

CLR1502

Lipid rafts and lipid molecules, such as cholesterol, exist in greater number in cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment than in normal cells.88 The fluorescent alkylphosphocholine derivative CLR1501 labels glial and other tumors by targeting these lipid rafts.89 A CLR1501 analog, CLR1502, conjugated to a NIR fluorophore (excitation 760 nM, emission 778 nM) labels mouse glial tumors with a high TNR of 9.28+/− 1.08) (Table 1).90 In fact the TNR signal is significantly better than the TNR calculated by these authors for 5-ALA (TNR = 4.81+/− 0.92).90 CLR1502 also labels the tumor margin.90 The greatest limitation with this agent is its need to be administered 4 days before imaging.90 Cellectar Biosciences Inc. (Madison, Wisconsin, USA) owns licensing and patent rights to CLR1501 and 1502. Preclinical studies with the parent CLR agent have shown safety in animal and human models, and clinical trials to test the safety and efficacy of CLR1501 and 1502 are in the planning stages.90

Integrin αvβ3 targeting

Integrin receptors, especially αvβ3, are highly expressed on the surface of glioma cells and on endothelial cells in glioma tissue.91 The tripeptide sequence, RGD (composed of arginine, glycine, and aspartic acid), can bind to integrin receptors, including αvβ3. In a subcutaneous U-87 MG xenograft model, RGD peptides conjugated to Cy5.5 label glioma cells with a high TNR after 4 hours.92, 93 A Cy5.5 conjugated non-peptide RGD mimetic is similarly effective at labeling U-87 MG xenografts.94 In an orthotopic glioma model, RGD-Cy5.5 labeled tumor cells with a TNR of 2.64 +/− 0.20 two hours after injection.95 Using the NIR dye, IRDye 800CW (excitation 774 nM, emission 805 nM) conjugated to RGD, Huang et al. developed another αvβ3-targeting molecular imaging agent (Table 1), IRDye 800CW-RGD peptide, that labels tumor margins well when examined ex vivo and permits ex vivo surgical resection of the tumor.96 The IRDye 800CW-RGD peptide labeled intracranial tumors with high specificity 24-48 hours after injection, with a maximum TNR after 48 hours of 3.26+/−0.18.96 An iron-oxide nanoparticle coupled to RGD peptides and IRDye 800CW also demonstrated labeling efficiency ex vivo.97 αvβ3-targeting has been combined with other targeting agents, such as angiopep-2 to label orthotopic intracranial tumors 67 and MMP2-ACPs to label U-87 MG cells in vitro.98 Given their ability to target both tumor vasculature and glioma cells, RGD molecular imaging agents also show promise for FGS.

The benefits of using multiple fluorophores for different purposes

The use of multiple agents with differing cellular targets and fluorescent spectra in the surgical setting would, in theory, allow for simultaneous identification of the main tumor mass as well as the difficult to visualize peripheral margins. With the addition of other agents it is also possible to identify important structures not always visible until injury, such as the vasculature, which may affect extent of safe resection. Various means of imaging these different anatomical features exist. For example, ICG video angiography is used routinely for visualizing vascular anatomy and determining patency of both arterial and venous structures.46, 99 Fluorescent labeling of peripheral and central nerves also can be achieved by the use of myelin binding agents, including NP41,100, 101 GE3111,102 BMB and GE3082,103 and may possibly be used for labeling white matter tracts. Delineation of these tracts and avoidance may ultimately lead to a lower extent of postoperative neurologic deficit. Nanoparticles labeled with the tumor staining dyes coomassie brilliant blue and methylene blue allow for visualization of tumor cells with very little dye application.104 Coomassie brilliant blue is safe for injection in humans.105 Coomassie brilliant blue conjugated to the F3 peptide, which is very specific for tumor tissue and targets nucleolin, is an example of a molecular imaging agent visible without the use of a fluorescent microscope.106 Combining visible spectrum blue dyes and fluorescent indocyanine green is currently used clinically for sentinel lymph node mapping and increases detection accuracy rate.9 The continued molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment also should yield the development of more tailored molecular imaging agents for the entire tumor microenvironment.

Special considerations

Clinical research on 5-ALA has brought to light certain limitations that also may be relevant for other fluorescent molecular imaging agents. After the administration of 5-ALA, patients need to be sheltered from bright light, and operating room lights must be dimmed during surgery to avoid interference with the red fluorescent signal.28 Issues with cortical overhang blocking fluorescent signals, the effect of excitation light distance from tumor tissue influencing fluorescence intensity, and even factors as mundane as old xenon bulbs reducing the fluorescent signal will need to be taken into consideration for all fluorescent imaging agents.28 In addition, findings that the emission spectra of 5-ALA is not the same in the main tumor and at the margins suggests that tissue pH may influence fluorescence emission wavelengths,107 which may be relevant to fluorescent imaging with other molecular imaging agents. Finally, the high cost of obtaining FDA approval for the development of molecular imaging agents, especially ones that target so-called “orphan diseases,” is a major barrier to bringing this technology to the clinic.108, 109

Conclusions

Despite the considerations that must be addressed and the preclinical nature of the targeted agent data thus far, studies that use non-targeted agents and 5-ALA during glioma resection clearly demonstrate a benefit in EOR and 6 month progression-free survival. Optical imaging with additional targeted fluorescent molecular agents may allow for even greater tumor specificity without significantly altering the current surgical flow. Given the accumulating evidence for the importance of EOR in the treatment of glioma, the limits of conventional stereotactic navigation, intraoperative shift as well as the expense and complexity of treating residual disease, additional studies of agents and technologies to augment resection are indicated.

Acknowledgments

We thank James P. Basilion for his contribution of the GB119 figure. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R01-CA179956 and by the Tabitha Yee-May Lou Endowment Fund for Brain Cancer Research. AES is supported by the Cristal Chair in Neurosurgical Oncology at University Hospitals Case Medical Center as well as the Kimble fund for Neuro-Oncology at University Hospitals.

Abbreviations list

- 5-ALA

5-aminolevulinic acid

- ACP

activating cell penetrating peptide

- APC

alkylphosphocholine

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EOR

extent of resection

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention effect

- FDA

U.S. food and drug administration

- FGS

fluorescent guided surgery

- GBM

glioblastoma

- ICG

indocyanine green

- iMRI

intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging

- IND

investigational new drug

- LMN

live molecular navigation; low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NIR

near-infrared

- PARP-1

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

- PpIX

porphyrins

- RGD

tripeptide composed of arginine, glycine, and aspartic acid

- TNR

tumor to normal ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Dr. Sloan holds an IND exemption for the use of 5-ALA for fluorescent guided resection of malignant brain tumors.

References

- 1.D'Amico RS, Kennedy BC, Bruce JN. Neurosurgical oncology: advances in operative technologies and adjuncts. J Neurooncol. 2014;119(3):451–63. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanai N, Polley MY, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(1):3–8. doi: 10.3171/2011.2.jns10998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keles GE, Anderson B, Berger MS. The effect of extent of resection on time to tumor progression and survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme of the cerebral hemisphere. Surgical Neurology. 1999;52(4):371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(99)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL, Shi W, DeMonte F, Lang FF, McCutcheon IE, Hassenbusch SJ, Holland E, Hess K, Michael C, Miller D, Sawaya R. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(2):190–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marko NF, Weil RJ, Schroeder JL, Lang FF, Suki D, Sawaya RE. Extent of resection of glioblastoma revisited: personalized survival modeling facilitates more accurate survival prediction and supports a maximum-safe-resection approach to surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):774–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stummer W, van den Bent MJ, Westphal M. Cytoreductive surgery of glioblastoma as the key to successful adjuvant therapies: new arguments in an old discussion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153(6):1211–8. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colditz MJ, Jeffree RL. Aminolevulinic acid (ALA)-protoporphyrin IX fluorescence guided tumour resection. Part 1: Clinical, radiological and pathological studies. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(11):1471–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foersch S, Heimann A, Ayyad A, Spoden GA, Florin L, Mpoukouvalas K, Kiesslich R, Kempski O, Goetz M, Charalampaki P. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for diagnosis and histomorphologic imaging of brain tumors in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi C, Du Y, Ye J, Kou D, Qiu J, Wang J, Tian J, Chen X. Intraoperative imaging-guided cancer surgery: from current fluorescence molecular imaging methods to future multi-modality imaging technology. Theranostics. 2014;4(11):1072–84. doi: 10.7150/thno.9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen QT, Tsien RY. Fluorescence-guided surgery with live molecular navigation--a new cutting edge. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(9):653–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitley MJ, Weissleder R, Kirsch DG. Tailoring Adjuvant Radiation Therapy by Intraoperative Imaging to Detect Residual Cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2015;25(4):313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu JT, Meza D, Sanai N. Trends in fluorescence image-guided surgery for gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2014;75(1):61–71. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyers JD, Doane T, Burda C, Basilion JP. Nanoparticles for imaging and treating brain cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2013;8(1):123–43. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pogue BW, Gibbs-Strauss S, Valdes PA, Samkoe K, Roberts DW, Paulsen KD. Review of Neurosurgical Fluorescence Imaging Methodologies. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2010;16(3):493–505. doi: 10.1109/JSTQE.2009.2034541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De la Garza-Ramos R, Bydon M, Macki M, Huang J, Tamargo RJ, Bydon A. Fluorescent techniques in spine surgery. Neurol Res. 2014;36(10):928–38. doi: 10.1179/1743132814Y.0000000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orosco RK, Tsien RY, Nguyen QT. Fluorescence imaging in surgery. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2013;6:178–87. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2013.2240294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissleder R, Ntziachristos V. Shedding light onto live molecular targets. Nat Med. 2003;9(1):123–128. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keereweer S, Kerrebijn JD, van Driel PB, Xie B, Kaijzel EL, Snoeks TJ, Que I, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, Mieog JS, Vahrmeijer AL, van de Velde CJ, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Lowik CW. Optical image-guided surgery--where do we stand? Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13(2):199–207. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondal SB, Gao S, Zhu N, Liang R, Gruev V, Achilefu S. Real-time Fluorescence Image-Guided Oncologic Surgery. Advances in cancer research. 2014;124:171–211. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-411638-2.00005-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LWK, Nie S. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotech. 2004;22(8):969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghoroghchian PP, Therien MJ, Hammer DA. In vivo fluorescence imaging: a personal perspective. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1(2):156–67. doi: 10.1002/wnan.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewelt C, Floeth FW, Felsberg J, Steiger HJ, Sabel M, Langen KJ, Stoffels G, Stummer W. Finding the anaplastic focus in diffuse gliomas: the value of Gd-DTPA enhanced MRI, FET-PET, and intraoperative, ALA-derived tissue fluorescence. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113(7):541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie J, Chen K, Huang J, Lee S, Wang J, Gao J, Li X, Chen X. PET/NIRF/MRI triple functional iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2010;31(11):3016–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertrand N, Wu J, Xu X, Kamaly N, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanotechnology: the impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;66:2–25. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maeda H. Macromolecular therapeutics in cancer treatment: The EPR effect and beyond. J Control Release. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arias JL. Drug targeting strategies in cancer treatment: an overview. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11(1):1–17. doi: 10.2174/138955711793564024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts DW, Valdes PA, Harris BT, Hartov A, Fan X, Ji S, Leblond F, Tosteson TD, Wilson BC, Paulsen KD. Glioblastoma multiforme treatment with clinical trials for surgical resection (aminolevulinic acid). Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2012;23(3):371–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tonn JC, Stummer W. Fluorescence-guided resection of malignant gliomas using 5-aminolevulinic acid: practical use, risks, and pitfalls. Clin Neurosurg. 2008;55:20–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awad AJ, Sloan A. The Use of 5-ALA in Glioblastoma Resection: Two Cases with Long-Term Progression-Free Survival. Cureus. 2014;6(9) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy JC, Pottier RH. New trends in photobiology: Endogenous protoporphyrin IX, a clinically useful photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 1992;14(4):275–292. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(92)85108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen HJ, Group AL-GS. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cordova JS, Gurbani SS, Holder CA, Olson JJ, Schreibmann E, Shi R, Guo Y, Shu HG, Shim H, Hadjipanayis CG. Semi-Automated Volumetric and Morphological Assessment of Glioblastoma Resection with Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. Mol Imaging Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11307-015-0900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau D, Hervey-Jumper SL, Chang S, Molinaro AM, McDermott MW, Phillips JJ, Berger MS. A prospective Phase II clinical trial of 5-aminolevulinic acid to assess the correlation of intraoperative fluorescence intensity and degree of histologic cellularity during resection of high-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.3171/2015.5.JNS1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nabavi A, Thurm H, Zountsas B, Pietsch T, Lanfermann H, Pichlmeier U, Mehdorn M. Five-aminolevulinic acid for fluorescence-guided resection of recurrent malignant gliomas: a phase II study. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(6):1070–6. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360128.03597.C7. discussion 1076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Della Puppa A, Ciccarino P, Lombardi G, Rolma G, Cecchin D, Rossetto M. 5-Aminolevulinic acid fluorescence in high grade glioma surgery: surgical outcome, intraoperative findings, and fluorescence patterns. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:232561. doi: 10.1155/2014/232561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamp MA, Felsberg J, Sadat H, Kuzibaev J, Steiger HJ, Rapp M, Reifenberger G, Dibue M, Sabel M. 5-ALA-induced fluorescence behavior of reactive tissue changes following glioblastoma treatment with radiation and chemotherapy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2015;157(2):207–13. doi: 10.1007/s00701-014-2313-4. discussion 213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Utsuki S, Oka H, Sato S, Shimizu S, Suzuki S, Tanizaki Y, Kondo K, Miyajima Y, Fujii K. Histological examination of false positive tissue resection using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence guidance. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2007;47(5):210–3. doi: 10.2176/nmc.47.210. discussion 213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diez Valle R, Tejada Solis S, Idoate Gastearena MA, Garcia de Eulate R, Dominguez Echavarri P, Aristu Mendiroz J. Surgery guided by 5-aminolevulinic fluorescence in glioblastoma: volumetric analysis of extent of resection in single-center experience. J Neurooncol. 2011;102(1):105–13. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Idoate MA, Diez Valle R, Echeveste J, Tejada S. Pathological characterization of the glioblastoma border as shown during surgery using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence. Neuropathology. 2011;31(6):575–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2011.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauser SB, Kockro RA, Actor B, Sarnthein J, Bernays RL. Combining 5-ALA Fluorescence and Intraoperative MRI in Glioblastoma Surgery: A Histology-Based Evaluation. Neurosurgery. 2015 doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valdes PA, Kim A, Brantsch M, Niu C, Moses ZB, Tosteson TD, Wilson BC, Paulsen KD, Roberts DW, Harris BT. delta-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX concentration correlates with histopathologic markers of malignancy in human gliomas: the need for quantitative fluorescence-guided resection to identify regions of increasing malignancy. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(8):846–56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acerbi F, Cavallo C, Broggi M, Cordella R, Anghileri E, Eoli M, Schiariti M, Broggi G, Ferroli P. Fluorescein-guided surgery for malignant gliomas: a review. Neurosurg Rev. 2014;37(4):547–57. doi: 10.1007/s10143-014-0546-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acerbi F, Broggi M, Eoli M, Anghileri E, Cavallo C, Boffano C, Cordella R, Cuppini L, Pollo B, Schiariti M, Visintini S, Orsi C, La Corte E, Broggi G, Ferroli P. Is fluorescein-guided technique able to help in resection of high-grade gliomas? Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36(2):E5. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.FOCUS13487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acerbi F, Broggi M, Eoli M, Anghileri E, Cuppini L, Pollo B, Schiariti M, Visintini S, Orsi C, Franzini A, Broggi G, Ferroli P. Fluorescein-guided surgery for grade IV gliomas with a dedicated filter on the surgical microscope: preliminary results in 12 cases. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2013;155(7):1277–1286. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwake M, Stummer W, Suero Molina EJ, Wolfer J. Simultaneous fluorescein sodium and 5-ALA in fluorescence-guided glioma surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2015;157(5):877–9. doi: 10.1007/s00701-015-2401-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim EH, Cho JM, Chang JH, Kim SH, Lee KS. Application of intraoperative indocyanine green videoangiography to brain tumor surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153(7):1487–95. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1046-x. discussion 1494-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ewelt C, Nemes A, Senner V, Wölfer J, Brokinkel B, Stummer W, Holling M. Fluorescence in neurosurgery: Its diagnostic and therapeutic use. Review of the literature. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 2015;148:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haglund MM, Berger MS, Hochman DW. Enhanced optical imaging of human gliomas and tumor margins. Neurosurgery. 1996;38(2):308–17. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199602000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen DA, Spence AM, Carski T, Berger MS. Indocyanine green (ICG) staining and demarcation of tumor margins in a rat glioma model. Surg Neurol. 1993;40(6):451–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Löser R, Pietzsch J. Cysteine cathepsins: their role in tumor progression and recent trends in the development of imaging probes. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2015;3 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2015.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strojnik T, Kavalar R, Trinkaus M, Lah TT. Cathepsin L in glioma progression: comparison with cathepsin B. Cancer Detect Prev. 2005;29(5):448–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sivaparvathi M, Yamamoto M, Nicolson GL, Gokaslan ZL, Fuller GN, Liotta LA, Sawaya R, Rao JS. Expression and immunohistochemical localization of cathepsin L during the progression of human gliomas. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1996;14(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00157683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heal WP, Dang THT, Tate EW. Activity-based probes: discovering new biology and new drug targets. Chemical Society Reviews. 2011;40(1):246–257. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00004c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cutter JL, Cohen NT, Wang J, Sloan AE, Cohen AR, Panneerselvam A, Schluchter M, Blum G, Bogyo M, Basilion JP. Topical application of activity-based probes for visualization of brain tumor tissue. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ofori LO, Withana NP, Prestwood TR, Verdoes M, Brady JJ, Winslow MM, Sorger J, Bogyo M. Design of Protease Activated Optical Contrast Agents That Exploit a Latent Lysosomotropic Effect for Use in Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(9):1977–88. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stroud MR, Hansen SJ, Olson JM. In vivo bio-imaging using chlorotoxin-based conjugates. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(38):4362–71. doi: 10.2174/138161211798999375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butte PV, Mamelak A, Parrish-Novak J, Drazin D, Shweikeh F, Gangalum PR, Chesnokova A, Ljubimova JY, Black K. Near-infrared imaging of brain tumors using the Tumor Paint BLZ-100 to achieve near-complete resection of brain tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36(2):E1. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.FOCUS13497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Veiseh M, Gabikian P, Bahrami SB, Veiseh O, Zhang M, Hackman RC, Ravanpay AC, Stroud MR, Kusuma Y, Hansen SJ, Kwok D, Munoz NM, Sze RW, Grady WM, Greenberg NM, Ellenbogen RG, Olson JM. Tumor paint: a chlorotoxin:Cy5.5 bioconjugate for intraoperative visualization of cancer foci. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):6882–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deshane J, Garner CC, Sontheimer H. Chlorotoxin inhibits glioma cell invasion via matrix metalloproteinase-2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(6):4135–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kesavan K, Ratliff J, Johnson EW, Dahlberg W, Asara JM, Misra P, Frangioni JV, Jacoby DB. Annexin A2 is a molecular target for TM601, a peptide with tumor-targeting and anti-angiogenic effects. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(7):4366–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blaze Bioscience I. Safety Study of BLZ-100 in Adult Subjects With Glioma Undergoing Surgery. [December 22, 2014];2014 ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] [cited 2000-2014]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02234297.

- 62.Akcan M, Stroud MR, Hansen SJ, Clark RJ, Daly NL, Craik DJ, Olson JM. Chemical re-engineering of chlorotoxin improves bioconjugation properties for tumor imaging and targeted therapy. J Med Chem. 2011;54(3):782–7. doi: 10.1021/jm101018r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng Y, Zhao J, Qiao W, Chen K. Recent advances in diagnosis and treatment of gliomas using chlorotoxin-based bioconjugates. American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2014;4(5):385–405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen J, Zhan C, Xie C, Meng Q, Gu B, Li C, Zhang Y, Lu W. Poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(D,L-lactide acid) micelles anchored with angiopep-2 for brain-targeting delivery. J Drug Target. 2011;19(3):197–203. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2010.483517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xin H, Jiang X, Gu J, Sha X, Chen L, Law K, Chen Y, Wang X, Jiang Y, Fang X. Angiopep-conjugated poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles as dual-targeting drug delivery system for brain glioma. Biomaterials. 2011;32(18):4293–4305. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan H, Wang J, Yi P, Lei H, Zhan C, Xie C, Feng L, Qian J, Zhu J, Lu W, Li C. Imaging brain tumor by dendrimer-based optical/paramagnetic nanoprobe across the blood-brain barrier. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47(28):8130–2. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12007g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yan H, Wang L, Wang J, Weng X, Lei H, Wang X, Jiang L, Zhu J, Lu W, Wei X, Li C. Two-order targeted brain tumor imaging by using an optical/paramagnetic nanoprobe across the blood brain barrier. ACS Nano. 2012;6(1):410–20. doi: 10.1021/nn203749v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei X, Zhan C, Chen X, Hou J, Xie C, Lu W. Retro-inverso isomer of Angiopep-2: a stable d-peptide ligand inspires brain-targeted drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(10):3261–8. doi: 10.1021/mp500086e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruan S, Qian J, Shen S, Chen J, Zhu J, Jiang X, He Q, Yang W, Gao H. Fluorescent carbonaceous nanodots for noninvasive glioma imaging after angiopep-2 decoration. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25(12):2252–9. doi: 10.1021/bc500474p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruan S, Yuan M, Zhang L, Hu G, Chen J, Cun X, Zhang Q, Yang Y, He Q, Gao H. Tumor microenvironment sensitive doxorubicin delivery and release to glioma using angiopep-2 decorated gold nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2015;37:425–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hao Y, Wang L, Zhao Y, Meng D, Li D, Li H, Zhang B, Shi J, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Zhang Y. Targeted Imaging and Chemo-Phototherapy of Brain Cancer by a Multifunctional Drug Delivery System. Macromol Biosci. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ren J, Shen S, Wang D, Xi Z, Guo L, Pang Z, Qian Y, Sun X, Jiang X. The targeted delivery of anticancer drugs to brain glioma by PEGylated oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified with angiopep-2. Biomaterials. 2012;33(11):3324–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kurzrock R, Gabrail N, Chandhasin C, Moulder S, Smith C, Brenner A, Sankhala K, Mita A, Elian K, Bouchard D, Sarantopoulos J. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and activity of GRN1005, a novel conjugate of angiopep-2, a peptide facilitating brain penetration, and paclitaxel, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(2):308–16. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao H, Zhang S, Cao S, Yang Z, Pang Z, Jiang X. Angiopep-2 and activatable cell-penetrating peptide dual-functionalized nanoparticles for systemic glioma-targeting delivery. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(8):2755–63. doi: 10.1021/mp500113p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mei L, Zhang Q, Yang Y, He Q, Gao H. Angiopep-2 and activatable cell penetrating peptide dual modified nanoparticles for enhanced tumor targeting and penetrating. Int J Pharm. 2014;474(1-2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maire CL, Ligon KL. Molecular pathologic diagnosis of epidermal growth factor receptor. Neuro-Oncology. 2014;16(Suppl 8):viii1–viii6. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cheng Y, Meyers JD, Agnes RS, Doane TL, Kenney ME, Broome AM, Burda C, Basilion JP. Addressing brain tumors with targeted gold nanoparticles: a new gold standard for hydrophobic drug delivery? Small. 2011;7(16):2301–6. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cheng Y, Meyers JD, Broome AM, Kenney ME, Basilion JP, Burda C. Deep penetration of a PDT drug into tumors by noncovalent drug-gold nanoparticle conjugates. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(8):2583–91. doi: 10.1021/ja108846h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agnes RS, Broome AM, Wang J, Verma A, Lavik K, Basilion JP. An optical probe for noninvasive molecular imaging of orthotopic brain tumors overexpressing epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(10):2202–11. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Warram JM, de Boer E, Korb M, Hartman Y, Kovar J, Markert JM, Gillespie GY, Rosenthal EL. Fluorescence-guided resection of experimental malignant glioma using cetuximab-IRDye 800CW. Br J Neurosurg. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1056090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adams KE, Ke S, Kwon S, Liang F, Fan Z, Lu Y, Hirschi K, Mawad ME, Barry MA, Sevick-Muraca EM. Comparison of visible and near-infrared wavelength-excitable fluorescent dyes for molecular imaging of cancer. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2007;12(2):024017–024017-9. doi: 10.1117/1.2717137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burden-Gulley SM, Gates TJ, Burgoyne AM, Cutter JL, Lodowski DT, Robinson S, Sloan AE, Miller RH, Basilion JP, Brady-Kalnay SM. A novel molecular diagnostic of glioblastomas: detection of an extracellular fragment of protein tyrosine phosphatase mu. Neoplasia. 2010;12(4):305–16. doi: 10.1593/neo.91940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burden-Gulley SM, Qutaish MQ, Sullivant KE, Tan M, Craig SE, Basilion JP, Lu ZR, Wilson DL, Brady-Kalnay SM. Single cell molecular recognition of migrating and invading tumor cells using a targeted fluorescent probe to receptor PTPmu. Int J Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ijc.27838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burden-Gulley SM, Zhou Z, Craig SE, Lu ZR, Brady-Kalnay SM. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Tumors with a PTPmu Targeted Contrast Agent. Transl Oncol. 2013;6(3):329–37. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Herrmann K, Johansen M, Craig S, Vincent J, Howell M, Gao Y, Lu L, Erokwu B, Agnes R, Lu Z-R, Pokorski J, Basilion J, Gulani V, Griswold M, Flask C, Brady-Kalnay S. Molecular Imaging of Tumors Using a Quantitative T1 Mapping Technique via Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Diagnostics. 2015;5(3):318. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics5030318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Galia A, Calogero AE, Condorelli RA, Fraggetta F, La Corte C, Ridolfo F, Bosco P, Castiglione R, Salemi M. PARP-1 protein expression in glioblastoma multiforme. European Journal of Histochemistry : EJH. 2012;56(1):e9. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2012.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Irwin CP, Portorreal Y, Brand C, Zhang Y, Desai P, Salinas B, Weber WA, Reiner T. PARPi-FL - a Fluorescent PARP1 Inhibitor for Glioblastoma Imaging. Neoplasia. 2014;16(5):432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mollinedo F, Gajate C. Lipid rafts as major platforms for signaling regulation in cancer. Advances in Biological Regulation. 2015;57:130–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weichert JP, Clark PA, Kandela IK, Vaccaro AM, Clarke W, Longino MA, Pinchuk AN, Farhoud M, Swanson KI, Floberg JM, Grudzinski J, Titz B, Traynor AM, Chen HE, Hall LT, Pazoles CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Kuo JS. Alkylphosphocholine analogs for broad-spectrum cancer imaging and therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(240):240ra75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Swanson KI, Clark PA, Zhang RR, Kandela IK, Farhoud M, Weichert JP, Kuo JS. Fluorescent cancer-selective alkylphosphocholine analogs for intraoperative glioma detection. Neurosurgery. 2015;76(2):115–24. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tabatabai G, Weller M, Nabors B, Picard M, Reardon D, Mikkelsen T, Ruegg C, Stupp R. Targeting integrins in malignant glioma. Target Oncol. 2010;5(3):175–81. doi: 10.1007/s11523-010-0156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cheng Z, Wu Y, Xiong Z, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Near-infrared fluorescent RGD peptides for optical imaging of integrin alphavbeta3 expression in living mice. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(6):1433–41. doi: 10.1021/bc0501698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lanzardo S, Conti L, Brioschi C, Bartolomeo MP, Arosio D, Belvisi L, Manzoni L, Maiocchi A, Maisano F, Forni G. A new optical imaging probe targeting αVβ3 integrin in glioblastoma xenografts. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6(6):449–58. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alsibai W, Hahnenkamp A, Eisenblatter M, Riemann B, Schafers M, Bremer C, Haufe G, Holtke C. Fluorescent non-peptidic RGD mimetics with high selectivity for αVβ3 vs αIIbβ3 integrin receptor: novel probes for in vivo optical imaging. J Med Chem. 2014;57(23):9971–82. doi: 10.1021/jm501197c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hsu AR, Hou LC, Veeravagu A, Greve JM, Vogel H, Tse V, Chen X. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of integrin alphavbeta3 in an orthotopic glioblastoma model. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8(6):315–23. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang R, Vider J, Kovar JL, Olive DM, Mellinghoff IK, Mayer-Kuckuk P, Kircher MF, Blasberg RG. Integrin αvβ3-targeted IRDye 800CW near-infrared imaging of glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5731–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen K, Xie J, Xu H, Behera D, Michalski MH, Biswal S, Wang A, Chen X. Triblock copolymer coated iron oxide nanoparticle conjugate for tumor integrin targeting. Biomaterials. 2009;30(36):6912–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Crisp JL, Savariar EN, Glasgow HL, Ellies LG, Whitney MA, Tsien RY. Dual targeting of integrin αvβ3 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 for optical imaging of tumors and chemotherapeutic delivery. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(6):1514–25. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ferroli P, Acerbi F, Albanese E, Tringali G, Broggi M, Franzini A, Broggi G. Application of intraoperative indocyanine green angiography for CNS tumors: results on the first 100 cases. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;109:251–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-99651-5_40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Whitney MA, Crisp JL, Nguyen LT, Friedman B, Gross LA, Steinbach P, Tsien RY, Nguyen QT. Fluorescent peptides highlight peripheral nerves during surgery in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(4):352–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wu AP, Whitney MA, Crisp JL, Friedman B, Tsien RY, Nguyen QT. Improved facial nerve identification with novel fluorescently labeled probe. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(4):805–10. doi: 10.1002/lary.21411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cotero VE, Siclovan T, Zhang R, Carter RL, Bajaj A, LaPlante NE, Kim E, Gray D, Staudinger VP, Yazdanfar S, Tan Hehir CA. Intraoperative fluorescence imaging of peripheral and central nerves through a myelin-selective contrast agent. Mol Imaging Biol. 2012;14(6):708–17. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0555-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gibbs-Strauss SL, Nasr KA, Fish KM, Khullar O, Ashitate Y, Siclovan TM, Johnson BF, Barnhardt NE, Tan Hehir CA, Frangioni JV. Nerve-highlighting fluorescent contrast agents for image-guided surgery. Mol Imaging. 2011;10(2):91–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Orringer DA, Koo Y-EL, Chen T, Kim G, Hah HJ, Xu H, Wang S, Keep R, Philbert MA, Kopelman R, Sagher O. In Vitro Characterization of a Targeted, Dye-Loaded Nanodevice for Intraoperative Tumor Delineation. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5):965–972. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000344150.81021.AA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Taylor SH, Shillingford JP. CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF COOMASSIE BLUE. British Heart Journal. 1959;21(4):497–504. doi: 10.1136/hrt.21.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nie G, Hah HJ, Kim G, Lee YE, Qin M, Ratani TS, Fotiadis P, Miller A, Kochi A, Gao D, Chen T, Orringer DA, Sagher O, Philbert MA, Kopelman R. Hydrogel nanoparticles with covalently linked coomassie blue for brain tumor delineation visible to the surgeon. Small. 2012;8(6):884–91. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Montcel B, Mahieu-Williame L, Armoiry X, Meyronet D, Guyotat J. Two-peaked 5-ALA-induced PpIX fluorescence emission spectrum distinguishes glioblastomas from low grade gliomas and infiltrative component of glioblastomas. Biomed Opt Express. 2013;4(4):548–58. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nunn AD. Molecular imaging and personalized medicine: an uncertain future. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2007;22(6):722–39. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Henderson JA, Alexander BC, Smith JJ. The food and drug administration and molecular imaging agents: potential challenges and opportunities. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2(10):833–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]