Abstract

Introduction

Hookah (or waterpipe) use is increasing worldwide with implications for public health. Emerging adults (ages 18 to 25) have a higher risk for hookah use relative to younger and older groups. While research on the correlates of hookah use among emerging adults begins to accumulate, it may be useful to examine how transition-to-adulthood themes, or specific thoughts and feelings regarding emerging adulthood, are associated with hookah use. This study determined which transition-to-adulthood themes were associated with hookah use to understand the risk and protective factors for this tobacco-related behavior.

Methods

Participants (n=555; 79% female; mean age 22) completed surveys on demographic characteristics, transition-to-adulthood themes, hookah, and cigarette use.

Results

Past-month hookah use was more common than past-month cigarette use (16% versus 12%). In logistic regression analyses, participants who felt emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility were more likely to report hookah use. However, transition-to-adulthood themes were not statistically significantly related to cigarette use.

Conclusions

The profile for hookah use may differ from that of cigarettes among emerging adults. Themes of experimentation/possibility should be addressed in prevention programs on college campuses and popular recreational spots where emerging adults congregate. These findings can inform future studies of risk and protective factors for hookah use among emerging adults.

Keywords: Hookah use, waterpipe use, cigarette use, Emerging Adults, Young Adults, Prevention

1. Introduction

Hookah (or waterpipe) use is increasing worldwide with implications for public health. Hookah has deleterious effects on health akin to those of combustible cigarettes (Maziak, 2011), and is smoked slowly with individuals partaking in the activity for 30 minutes or more resulting in high levels of nicotine exposure (Nelson, 2015). In the United States (U.S.), tobacco control policies that apply to cigarette smoking do not similarly apply to hookah (Jawad, Kadi, Mugharbil, & Nakkash, 2014). For instance, in a study of the largest 100 U.S. cities, researchers found that 73 disallowed cigarette smoking in bars, but 69 of those cities may allow hookah use via exemptions (Primack et al., 2012). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Family Smoking and Prevention Control Act specifies (Section 907, titled ‘Tobacco Product Standards’) a ban on flavored cigarettes, but does not currently include hookah tobacco (United States, 2009). Policies also allow tobacco companies the ability to market and sell hookah, and related products, to vulnerable populations like emerging adults (ages 18 to 25) (Haddad, El-Shahawy, Ghadban, Barnett, & Johnson, 2015). Lax tobacco control policies may have allowed for hookah use to grow in popularity in the U.S.

Emerging adults have a higher risk for hookah use, relative to younger and older age groups (Cavazos-Rehg, Krauss, Kim, & Emery, 2015; Grekin & Ayna, 2012; Smith et al., 2011). In the U.S., recent research demonstrated that 25% of emerging adults reported lifetime hookah use (Villanti, Cobb, Cohn, Williams, & Rath, 2015), and demonstrated that 10% of college students reported past 30-day use (Jarrett, Blosnich, Tworek, & Horn, 2012). A systematic review of the literature suggested that the majority of hookah smokers were unaware of its potential risks (Haddad et al., 2015), and research has suggested that emerging adults perceive fewer negative consequences of hookah use compared with combustible cigarette use (Holtzman, Babinski, & Merlo, 2013; Heinz et al., 2013). Low perception of harm and low perceived addictiveness were positively associated with hookah use in the past year among emerging adults (Primack, Sidani, Agarwal, Shadel, Donny, & Eissenberg, 2008). Additional reasons for hookah use among emerging adults include believing that it is a good way to socialize with friends, and finding enjoyment in trying new things that are new and “hip” (Holtzman et al., 2013). Positive attitudes (e.g., hookah seems fun) and normative beliefs (e.g., hookah is socially acceptable) have been positively associated with hookah use among college students (Sidani, Shensa, Barnett, Cook, & Primack, 2014). Recent research demonstrated that hookah use predicted increased cigarette smoking over six months in a college sample in the U.S. (Doran, Godfrey, & Myers, 2015). Research has also shown that hookah smokers are significantly more likely to use other substances, including alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and cocaine compared to those who refrain from smoking hookah (Goodwin et al., 2014).

Emerging adulthood affords young people the opportunity for identity exploration in love, work, and perspective (Arnett, 2006). Arnett (2000) argued that a function of emerging adults’ identity exploration is engaging in risky behaviors. Sensation seeking, the yearning for intense experiences, motivates emerging adults to engage in risky behaviors, such as tobacco use, other substance use, and unprotected sex (Arnett, 2000). Young people may even engage in substance use as a function of identity exploration in emerging adulthood (Schwartz, Zamboanga, Luyckx, Meca, & Ritchie, 2013). In other words, emerging adults may use nicotine or other substances as a way of exploring a variety of different experiences, or they may use nicotine in order to alleviate uneasy feelings due to identity uncertainty. Risky behaviors like hookah use may be tolerated or encouraged during emerging adulthood (Sussman & Arnett, 2014).

While research on the correlates of hookah use among emerging adults begins to accumulate, it may be useful to examine how transition-to-adulthood themes, or specific thoughts and feelings regarding emerging adulthood, are associated with hookah use. Transition-to-adulthood themes have previously been found to be associated with risky behaviors (Allem, Lisha, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2013; Lisha et al., 2014). For example, feeling that emerging adulthood was a time for experimentation and possibility was associated with electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among college students (Allem, Forster, Neiberger, & Unger, 2015). The present study determined which transition-to-adulthood themes were associated with hookah use in order to better understand the risk and protective factors of this tobacco-related behavior among this population. Findings should prove useful for prevention/intervention programs, and in formulating future tobacco control policies.

2. Methods

2.1 Procedure

Study investigators worked with administrators from two colleges in the California State University (CSU) system in order to survey an ethnically and sociodemographically diverse sample of emerging adults. These colleges were among the most diverse in the CSU system (College Portraits, 2013), and located in the greater Los Angeles area. The sample of emerging adults (n=555; 79% female; mean age 22) was ethnically diverse with 46% Hispanic/Latino(a), 18% non-Hispanic white, 14% other, 12% African American, and 10% multiracial. Campus wide emails were distributed and administrators from each college campus posted flyers, and announced the current study on their respective CSU portal systems (accessible by their homepage). The recruitment material did not reference hookah or tobacco use but stated in general terms that the study was focused on college students’ health behaviors. Students received a description of the study, were informed about confidentiality, and electronically signed consent forms. A web-based survey allowed participants to click on a link on a computer or smart phone and electronically submit responses. Respondents were offered a five-dollar gift card after they had completed the survey. Data were de-identified for analytic purposes, and the IRB of the principal investigator’s university approved all procedures.

2.2 Measures

Transition-to-adulthood themes were assessed with the Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA) (Reifman, Arnett, & Colwell, 2007). The IDEA instrument has six subscales, which measure the main themes or pillars of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). The survey items were prompted with “Please think about this time in your life. By ‘time in your life,’ we are referring to the present time, plus the last few years that have gone by, and the next few years to come, as you see them. In short, you should think about a roughly five-year period, with the present time right in the middle. Is this time in your life a …” Responses for each item included “strongly disagree” coded 1, “somewhat disagree” coded 2, “agree” coded 3, and “strongly agree” coded 4. The subscales, corresponding reliability coefficient, and an example question are as follows: Identity Exploration (Cronbach’s alpha [α]=0.83) e.g., “time of finding out who you are?”, Experimentation/Possibilities (α=0.78) e.g., “time of many possibilities?”, Negativity/Instability (α=0.82) e.g., “time of confusion?”, Other-Focused e.g., (α=0.66) “time of responsibility for others?”, Self-Focused (α=0.77) e.g., “time of personal freedom?”, and Feeling “In-Between” (α=0.72) e.g., “time of feeling adult in some ways but not others?”.

The outcome of interest was past-month hookah use coded 1 “yes” and 0 “no”. Age was coded in years, and gender was coded 1 “male” or 0 “female.” Race/ethnicity was classified into five categories: 1) non-Hispanic white, 2) Hispanic or Latino/a, 3) Black or African American, 4) Other (Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander), and 5) multiracial. When race/ethnicity was included as a covariate in regression models it was coded 1 “non-Hispanic white” and 0 “not non-Hispanic white”.

2.3 Analysis plan

Initially, past-month hookah use was regressed on the subscales of emerging adulthood. Past-month hookah use was then regressed on the significant subscales while controlling for age, gender, and race/ethnicity. The events per variable (EPV) rule in logistic regression suggested separate models were appropriate. The EPV rule recommends 10 to 15 cases (“1s” in the dependent variable in this circumstance) for each explanatory variable in the model. This study had 91 past-month hookah smokers, suggesting more than 6 explanatory variables in any one model would run the high risk of being overfit (Greenland, 1989; Harrell, Lee, & Mark, 1996).

Given the two colleges used as sampling sites, students attending the same college may have similar hookah use behavior relative to those who do not. Appropriate diagnostics revealed that intraclass correlation (ICC) was small in this study (ICC = .04). Conclusions did not differ between fixed effects models and hierarchical models with a random intercept for school, so results from the fixed effects models were reported. In order to determine how hookah use may differ from combustible cigarette use, analyses were repeated for past-month combustible cigarette use (coded 1 “yes” and 0 “no”). For all analyses, the quantity of interest was calculated using the estimates from a multivariable analysis by simulation using 1,000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from a sampling distribution with mean equal to the maximum likelihood point estimates, and variance equal to the variance-covariance matrix of the estimates, with covariates held at their mean values (King, Tomz, & Wittenberg, 2000).

3. Results

Among the participants, 16% reported past-month hookah use, and 12% reported past-month cigarette use. Hookah use did not differ by gender, but significantly varied by age with older emerging adults being less likely to report past-month hookah use (p < .001). For example, going from 18 to 26 years of age was associated with a −20 (95% CI, −32 to −9) lower probability in hookah use. Hookah use varied by ethnicity with 44% of non-Hispanic whites, 28% of African Americans, 26% of multiracial, 15% of other, and 11% of Hispanics/Latino(a)s reporting past-month use, respectively. The difference in prevalence between non-Hispanic whites and other, as well as Hispanics/Latinos, was statistically significant (p < .01).

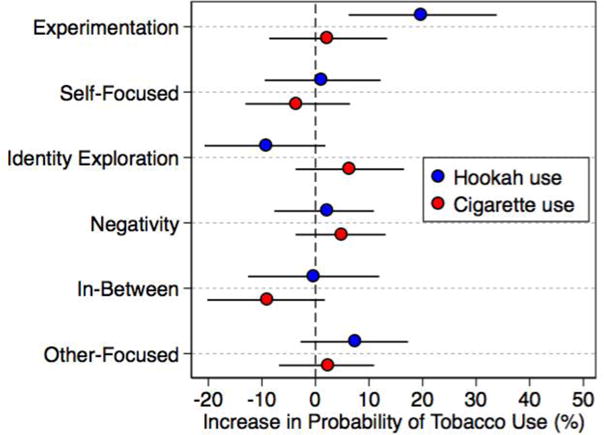

Participants who felt emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility were more likely to report hookah use (p <.05). A difference in score on the experimentation/possibility subscale between the 10th percentile and the 90th percentile was associated with a 20% (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 6% to 34%) higher probability of hookah use (Figure 1A). Conclusions did not change after controlling for age, gender, and race/ethnicity. The remaining IDEA subscales were insignificantly associated with hookah use. The IDEA subscales were insignificantly associated with past-month cigarette use.

Figure 1.

Shows the difference in predicted probabilities of past-month hookah and past-month cigarette use when the 10th and 90th percentile IDEA scores are included in computations with 95% confidence intervals. All estimates were arrived by use of 1000 random drawn sets of estimates from each respective coefficient covariance matrix with control variables held at their mean values.

4. Conclusion

The present study identified one transition-to-adulthood theme that was associated with past-month hookah use. Feeling that emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility was associated with an increased probability of hookah use, but not combustible cigarette use. Hookah use may be perceived as more experimental than cigarettes because of its growth in popularity in recent years making the behavior seem more new and exciting to emerging adults.

The profile for hookah use may differ from that of cigarettes among emerging adults, requiring specific intervention programs and policies to curb further use (Haddad et al., 2015). For example, in contrast to combustible cigarette use, hookah has not been associated with mental health problems or stress among college students in the U.S (Goodwin et al., 2014). Themes of emerging adulthood should be addressed in prevention programs on college campuses, and popular recreational spots where emerging adults congregate. Encouraging emerging adults to fulfill their need for experimentation with activities (e.g., mountaineering, snowboarding, surfing, scuba diving, business ventures, community service, internships) apart from engaging in hookah use could prove effective.

In the present sample, non-Hispanic whites were more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to report past month-hookah use which is in line with previous research on emerging tobacco products (Arrazola et al., 2015). Younger emerging adults were more likely than older emerging adults to report hookah use. This suggests prevention programs may need to be implemented for emerging adults right out of high school. Additionally, hookah use was more common than combustible cigarette use among this sample of emerging adults, which is similar to prior research (Lee, Bahreinifar, & Ling, 2014). A convenience sample of young adult hookah smokers in Southern California suggested that a majority of participants believed that hookah was not harmful to their health (Rezk-Hanna, & Macabasco-O’Connell, 2014), which may in part explain the higher prevalence in hookah use in the present sample.

4.1 Limitations

The lack of significance in the associations between hookah use and all the subscales of the IDEA instrument may be a result of measurement error. The IDEA instrument may not be a perfect measure of transition-to-adulthood themes, but it is gaining in popularity in assessing these constructs. Age of initiation in cigarette use may in part influence the current results. If initiation in cigarette smoking occurs earlier than hookah use, then the feeling of experimentation/possibility likely would not be associated with cigarette use in emerging adulthood. In other words, the earlier the behavior started the less likely that the behavior would feel like a form of emerging-adulthood experimentation. This study however does not know the age in which initiation in cigarette use or hookah use started. Hookah use was a dichotomous outcome, limiting the understanding of frequency of use. However, past-month measures of tobacco use are in line with prior research among emerging adults (Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2013; Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger 2015a; Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2015b). Emerging adults generally report smoking flavored tobacco in a hookah, however some use other substances such as marijuana (Sutfin, Song, Reboussin, &, Wolfson, 2014). The present study did not determine whether participants placed tobacco, or some other substance, in their hookah over the past month. While the present study’s sample overrepresented females, the findings did not differ by gender. Findings may not generalize to emerging adults in other regions of the U.S. or to those not enrolled in college. Future research should focus on sampling a nationally representative sample of emerging adults and testing additional hypotheses.

By appreciating the unique characteristics in emerging adulthood, the present findings move forward the literature on hookah use among emerging adults. Hookah use poses concerns to public health including emerging adults initiating in cigarette smoking (Doran et al., 2015), and other substance use (Goodwin et al., 2014). Emerging adults who initiate in hookah use, may transition to other nicotine products and struggle with nicotine dependence. With these public health concerns in mind, understanding the correlates of hookah use among a vulnerable population like emerging adults is of utmost importance. Findings from this study should be a point of departure for future studies looking to understand the risk and protective factors of hookah use among emerging adults.

Highlights.

Hookah use was more prevalent than cigarette use (16% vs. 12%) among participants.

Themes of experimentation/possibility were associated with hookah use.

The profile for hookah use may differ from that of cigarettes among young adults.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source:

Research reported in this publication was supported by Grant # P50CA180905 from the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or FDA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors:

Jon-Patrick Allem designed the concept of the study, was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. Jennifer B. Unger provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allem JP, Forster M, Neiberger A, Unger JB. Characteristics of emerging adulthood and e-cigarette use: Findings from a pilot study. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;50:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Lisha NE, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Emerging adulthood themes, role transitions and substance use among Hispanics in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2797–2800. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Role transitions in emerging adulthood are associated with smoking among Hispanics in Southern California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(11):1948–1951. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. The relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use among Hispanic emerging adults. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2015a;47(1):60–64. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.1001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Adverse childhood experiences and substance use among Hispanic emerging adults in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors. 2015b;50:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In: Jensen LA, editor. Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology: New synthesis in theory, research, and policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adulthood: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, McAfee T. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Kim Y, Emery SL. Risk factors associated with hookah use. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(12):1482–1490. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- College Portraits. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.collegeportraits.org.

- Doran N, Godfrey KM, Myers MG. Hookah use predicts cigarette smoking progression among college smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(11):1347–1353. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Grinberg A, Shapiro J, Keith D, McNeil MP, Taha F, Hart CL. Hookah use among college students: prevalence, drug use, and mental health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;141:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79(3):340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Ayna D. Waterpipe smoking among college students in the United States: a review of the literature. Journal of American College Health. 2012;60(3):244–249. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.589419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad L, El-Shahawy O, Ghadban R, Barnett TE, Johnson E. Waterpipe smoking and regulation in the United States: a comprehensive review of the literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12(6):6115–6135. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariate prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;15(4):361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz AJ, Giedgowd GE, Crane NA, Veilleux JC, Conrad M, Braun AR, Kassel JD. A comprehensive examination of hookah smoking in college students: use patterns and contexts, social norms and attitudes, harm perception, psychological correlates and co-occurring substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(11):2751–2760. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman AL, Babinski D, Merlo LJ. Knowledge and attitudes toward hookah usage among university students. Journal of American College Health. 2013;61(6):362–70. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.818000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett T, Blosnich J, Tworek C, Horn K. Hookah use among U.S. college students: results from the National College Health assessment II. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(10):1145–1153. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawad M, El Kadi L, Mugharbil S, Nakkash R. Waterpipe tobacco smoking legislation and policy enactment: a global analysis. Tobacco Control. 2014;1:i60–i65. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Tomz M, Wittenberg J. Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44(2):341–355. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2669316. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YO, Bahreinifar S, Ling PM. Understanding tobacco-related attitudes among college and noncollege young adult hookah and cigarette users. Journal of American College Health. 2014;62(1):10–18. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.842171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisha NE, Grana R, Sun P, Rohrbach L, Spruijt-Metz D, Reifman A, Sussman S. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Revised Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA-R) in a sample of continuation high school students. Evaluation & the health professions. 2014;37(2):156–177. doi: 10.1177/0163278712452664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. Hookah smoking seduces US young adults. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2015;3(4):277. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziak W. The global epidemic of waterpipe smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Hopkins M, Hallet C, Carroll MV, Zeller M, Dachille K, Donohue JM. US health policy related to hookah tobacco smoking. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(9):e47–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among US university students. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Arnett JJ, Colwell MJ. Emerging adulthood: Theory, assessment, and application. Journal of Youth Development. 2007;2(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rezk-Hanna M, Macabasco-O’Connell A, Woo M. Hookah smoking among young adults in southern California. Nursing Research. 2014;63(4):300–306. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Luyckx K, Meca A, Ritchie RA. Identity in emerging adulthood: Reviewing the field and looking forward. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1(2):96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani JE, Shensa A, Barnett TE, Cook RL, Primack BA. Knowledge, attitudes, and normative beliefs as predictors of hookah smoking initiation: a longitudinal study of university students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(6):647–654. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JR, Edland SD, Novotny TE, Hofstetter CR, White MM, Lindsay SP, Al-Delaimy WK. Increasing hookah use in California. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(10):1876–1879. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, Song EY, Reboussin BA, Wolfson M. What are young adults smoking in their hookahs? A latent class analysis of substances smoked. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(7):1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2014;37(2):147–155. doi: 10.1177/0163278714521812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States. Family smoking prevention and tobacco control and federal retirement reform. Washington, DC: U.S. G.P.O.; 2009. Retrieved from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ31/pdf/PLAW-111publ31.pdf (accessed on October 10, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Cobb CO, Cohn AM, Williams VF, Rath JM. Correlates of hookah use and predictors of hookah trail in U.S. young adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;48(6):742–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]