Abstract

Ligand-receptor interactions play important roles in many biological processes. Cyclic arginine – glycine – aspartic acid (RGD) containing peptides are known to mimic the binding domain of extracellular matrix protein fibronectin and selectively bind to a sub-set of integrin receptors. Here we report the tip enhanced Raman scattering (TERS) detection of RGD-functionalized nanoparticles bound to integrins produces a Raman scattering signal specific to the bound protein. These results demonstrate that this method can detect and differentiate between two different integrins (α5β1 and αvβ3) bound to RGD-conjugated gold nanoparticles both on surfaces and in a cancer cell membrane. In situ measurements of RGD nanoparticles bound to purified α5β1 and αvβ3 receptors attached to a glass surface provide reference spectra for a multivariate regression model. The TERS spectra observed from nanoparticles bound to cell membranes are analyzed using this regression model and the identity of the receptor can be determined. The ability to distinguish between receptors in the cell membrane provides a new tool to chemically characterize ligand-receptor recognition at molecular level, and provide chemical perspective on the molecular recognition of membrane receptors.

TOC image

Introduction

Signaling by membrane receptors is important for numerous biological processes, such as the regulation of signaling pathways, and thus receptor proteins are often targeted for therapeutic treatment. Understanding ligand-receptor binding is important for engineering specific interactions that affect cell signaling. In recent years, several microscopic methods, such as atomic force microscopy1, 2 and super resolution microscopy3, have been developed to visualize ligand-receptor binding events on cells, as well as to investigate the binding properties including binding kinetics and affinity. Although these microscopic methods allow for nanoscale imaging spatial resolution, and bring biophysical insights into ligand-receptor interaction, none of them provide molecular structural information in ligand-receptor binding sites. Chemical elucidation is typically obtained from crystal structures and nuclear magnetic resonance experiments4, which are performed on isolated proteins without interference from other cellular components. The ability to study chemical interactions involved in the signaling response of cells may significantly facilitate the process of drug discovery.

New technologies are key to providing the molecular insight into ligand-receptor binding chemistry needed. One promising technique is Raman spectroscopy, which measures the vibrational modes associated with the structure of molecules. The Raman spectrum encodes chemical-specific information regarding the identity (so called “chemical fingerprint”) of the molecules. Though Raman scattering is an inefficient process by nature, the application of plasmonic nanostructures produces significant enhancements, which makes Raman a highly sensitive method for chemical analysis, an effect commonly known as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)5, 6.

Tip-enhanced Raman scattering (TERS), utilizing a plasmonic nanostructure at the apex of a scanning probe microscope (SPM) tip, integrates the chemical sensitivity of SERS and nanoscale spatial resolution of SPM to enable molecular-level chemical imaging of surfaces, such as biomembranes7, 8. Recently our lab reported the Raman signals from immobilized protein receptors can be detected through a plasmonic coupling between a gold-ball TERS tip and a ligand-functionalized gold nanoparticle (GNPs)9, 10. Through protein mutation, we have been able to demonstrate amino acids near the ligand binding site are responsible for the observed TERS signal11. Initial studies on fixed cells show that this methodology can detect the amino acids involved in the ligand-binding interaction selectively in intact cell membranes12. These initial results suggest that TERS can provide chemical insights into cell membrane receptors, making it a promising new technology for investigating the chemical structure of membrane receptors and the chemical interactions that govern molecular recognition.

Integrins are a class of transmembrane receptors expressed in various cell types that are involved in tumor progression. Preclinical studies have shown that integrin antagonists, including monoclonal antibodies and arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) peptides, can inhibit tumor growth13, 14. However, there are a subset of integrins that can recognize the RGD sequence, and while cyclic-RGD peptides are believed to bind to αvβ3 receptors, there is also literature suggesting other integrins (e.g. αvβ5 and α5β1) can recognize this sequence15. In this paper we use two of the most prevalent integrin receptors, α5β1 and αvβ3, with reported affinity for our RGD peptide, to examine whether RGD-integrin binding can be differentiated in intact human colon cancer cells (SW480).

Experimental section

Materials

Gold nanoparticles (50 nm, citrate-GNPs) were purchased from BBI Solutions (Cardiff, UK). Cyclo-(arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-phenylalanine-cysteine) (cRGDfC or cRGD) peptide was synthesized by Peptide International (>90%, Louisville, KY). Purified human integrin receptors αvβ3 and α5β1 were purchased from EMD Millipore (>95%, Temecula, CA). Cell culture reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Cell fixative (4% paraformaldehyde) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ cm) from a Barnstead Nano-pure filtration system was used in all experiments.

Nanoparticle functionalization and characterization

A ligand exchange method was used to conjugate cRGD peptide onto the gold nanoparticles (Figure S1a). Briefly, 5 μL of 0.5 mM cRGD peptide was mixed with 1 mL of citrate-GNP (0.0568 mg mL−1, or 74.7 pM) colloid solution. The molar ratio of cRGD peptide to GNP was calculated to be 3.35×104:1. After 24 h vortex mixing, the colloidal solution was centrifuged (10000 rcf, 10 min) and re-suspended in pure water twice to remove the excessive and unbound peptides. The cRGD-conjugated nanoparticles (cRGD-GNPs) were reconstituted in 1 mL water and stored at 4ºC for later use.

Characterization of the nanoparticles was carried out by different methods. UV-Vis measurements were performed using Ocean Optics SD2000 spectrometer (Dunedin, FL) coupled with a DH-2000-BAL Deuterium-Tungsten halogen lamp. Raman spectra of the nanoparticles were acquired using an inVia confocal Raman microscope (Renishaw, UK) equipped with a 633nm HeNe laser (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ). Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measurements were performed using a Zetasizer Nano-ZS system (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). For UV-Vis and DLS measurements, 1 mL of the original citrate-GNPs and the as-prepared cRGD-GNPs were used. For Raman measurements, 100 μL of particles was concentrated to ~10 μL, dropped onto a clean glass slide, and sealed with a coverslip before the spectral acquisitions.

SERS detection of purified integrin receptors

10 µL of cRGD-GNPs was mixed with 2 µL of integrin α5β1 (0.5 mg mL−1), or 4 µL of integrin αvβ3 (0.25 mg mL−1), in 100 μL of 0.1× PBS solution. After 2 h vortex mixing, the mixture was concentrated to ~10 µL through centrifugation, then dropped onto a clean glass slide, and sealed with a coverslip. αvβ3-bound cRGD-GNPs, α5β1-bound cRGD-GNPs and cRGD-GNPs were prepared for measurements in a home-built Raman microscope system. Multiple consecutive Raman spectra were collected with 0.77 mW laser power and 10 s acquisition time. Only spectra with notable enhanced Raman bands were selected for Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) analysis.

Integrin receptor immobilization on glass

Step-by-step integrin immobilization procedure was shown in Figure S2. Glass slides were rinsed sequentially with water and ethanol, and then oxidized with air plasma for 5 min. The cleaned slides were immersed in silane/ethanol solution (4% (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane in 95% ethanol, APTES) for 15 min. The slides were rinsed with ethanol and water, and then dried at 60°C for 1 h The silanized slides were promptly incubated in a glutaraldehyde solution (8%) for 30 min and rinsed thrice with water. The slides were then baked at 60°C for another 1 h. The excessive aldehyde groups remaining on the slides were used to bind the integrin α5β1 or integrin αvβ3 by incubating the slides for 1 h with 0.1× PBS solution containing 10 μg mL−1 of the appropriate receptor (α5β1 or αvβ3) and 5 mM sodium cyanoborohydride. After rinsing off the unbound integrin receptors with 0.1× PBS, unreacted aldehyde groups were passivated by incubating with ethanolamine solution (100 mM in 0.1× PBS) for 30 min. The integrin-immobilized glass slides were then rinsed with 0.1× PBS and dried in air.

TERS sample preparation

For TERS measurements on immobilized integrin receptors, 20 μL of the as-prepared cRGD-GNPs was diluted to 100 μL (in 0.1× PBS containing 5 mM sodium cyanoborohydride), and then incubated with integrin-immobilized glass slides for 2 h at room temperature. Then, samples were rinsed and dried in air before TERS experiments.

For TERS measurements on cells, SW480 cell were seeded on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips to enhance attachment. After 24-h attachment, cells were rinsed with 0.1× PBS and incubated with 100 μL of cRGD-GNPs for 2 h. the unadsorbed nanoparticles were removed by rinsing with 0.1× PBS several times. Cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS) for 10 min, rinsed with 0.1× PBS and water, and dried before TERS experiments. The SW480 cells were cultured following a previously published procedure16.

TERS imaging

TERS measurements were carried out with a combined AFM-Raman system that has been previously reported10, 11. The system incorporates a commercial AFM microscope (Nanonics MV4000) and a home-built Raman spectrometer containing a Horiba Jobin Yvon monochromator. A 633 nm HeNe excitation laser was used to illuminate the sample. Radial polarization of the laser was achieved using a liquid-crystal mode converter (ArcOptix), producing a longitudinal mode at the focus that results in increased enhancement and better spatial resolution from the TERS tip8, 17. The TERS tip is a chemical mechanical polished gold nanoparticle (diameter of 100–200 nm) attached to the apex of a transparent glass cantilever (Nanonics Imaging Ltd. Israel). A long working distance dark-field objective (50, NA = 0.5, LMPlanFLN, Olympus) was used for both TERS and dark-field imaging. The collected TERS signal was filtered by a 633 nm dichroic beamsplitter and a 633 nm long pass filter (RazorEdge, Semrock), dispersed by a 600 g mm−1 grating, and collected by a CCD camera cooled at −70°C. TERS maps were obtained by scanning the sample stage under the TERS tip positioned in the laser focus. The acquisition time was 1s per pixel and laser power was measured to be 0.8–1.1 mW to avoid damaging the samples.

Data analysis

TERS spectra and maps were plotted using Matlab R2015a (Mathworks, Natic, MA) without pre-processing. Raw SERS spectra of the nanoparticle-bound integins were preprocessed through a weighted least squares (WLS, Whittaker filter, 5th order polynomial) automatic baseline subtraction to remove differences due only to the background in each spectrum. These spectra were used to decompose the pure components of the SERS data using multi-variant curve resolution (MCR), and further used to classify the TERS data in order to determine the class of each spectrum in the TERS map. TERS maps and score maps were reconstructed in MATLAB according to single-peak intensities and MCR scores, respectively.

Results

The experiments reported here build from previous results where a ligand-functionalized nanoparticle detected by TERS12 provide a Raman signature characteristic of the protein receptor bound to the nanoparticle. The plasmonic nanoprobe was synthesized consisting of 50 nm gold nanoparticles (GNPs), conjugated with a cyclo-(arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-phenylalanine-cysteine) (cRGDfC, or cRGD) peptides through covalent Au-S bond (see Supporting Information, Figure S1a). The functionalized nanoparticles were characterized by UV-Vis, Raman spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering (see SI, Table S1). After ligand conjugation, the plasma resonance peak shifted from 531 to 532 nm (see SI, Figure S1b), and hydrodynamic diameter changed from 52.6 to 49.2 nm. In addition, the appearance of 1003 cm−1 Raman band (see SI, Figure S1c), assigned to phenylalanine from the cRGD ligand, indicate the successful formation of cRGD-conjugated GNPs (cRGD-GNPs).

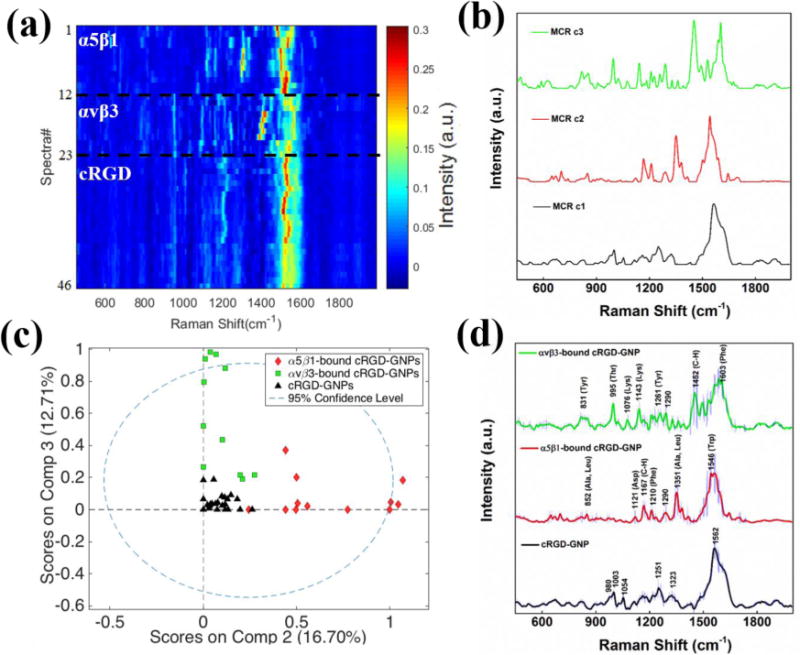

In order to identify the Raman signal of each receptor and generate a set of reference spectra for each integrin, SERS experiments were performed on the cRGD-GNPs incubated either with purified α5β1 or αvβ3 receptors. Multiple spectra from just the cRGD-GNPs, α5β1-bound cRGD-GNPs, and αvβ3-bound cRGD-GNPs were acquired in 0.1X PBS solution where nanoparticle clusters formed plasmon-enhanced “hot spots”. Changes in spectra intensities with time (see SI, Figure S2) are attributed to reversible receptor binding and movement in and out of the “hot spots”. The spectra exhibiting Raman peaks were selected to form a SERS calibration dataset (Figure 1a). This calibration dataset, consisting of spectra from cRGD-GNPs (n=23), α5β1-bound cRGD-GNPs (n=12), and αvβ3-bound cRGD-GNPs (n=11), was analyzed with multivariate curve resolution (MCR), a chemometric method that analyzes the variance in the data and generates components associated with the spectral composition. The MCR analysis produced 3 pure components that account for approximately 90% of the total variance in the SERS dataset (Figure 1b). Component 1 (c1, 60.14% variance) closely resembles the SERS spectrum obtained from the cRGD-GNPs; component 2 (c2, 16.70% variance) is attributed to α5β1-bound cRGD-GNPs; and component 3 (c3, 12.71% variance) is attributed to αvβ3-bound cRGD-GNPs. The average SERS spectra from the pure systems associated with each component are shown in Figure 1d for comparison. MCR score plot of the SERS spectra (Figure 1c) shows how the cRGD-GNPs and α5β1- and αvβ3-bound nanoparticles can be reduced to two orthogonal dimensions, clearly distinguishing between the integrin receptors.

Figure 1.

(a) Heat map constructed with normalized SERS spectra of cRGD-GNPs (n=23), α5β1-bound cRGD-GNPs (n=12), and αvβ3-bound cRGD-GNPs (n=11). (b) Three pure components generated from SERS data by MCR analysis. (c) MCR scores of the SERS data on two major components (c2 and c3). (d) Average SERS spectra. Shaded area represents standard deviation of the spectra at each frequency.

Analysis of the SERS spectra (Figure 1d) shows the observed vibrational bands correlate with the amino acids found in the RGD binding site of the α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins18, 19. Raman bands observed in α5β1-bound cRGD-GNPs are assigned to amino acid associated C-H bending (1290, 1167 cm−1), and Ala/Leu (1351 cm−1), Trp (1546 cm−1), Phe (1210 cm−1)18, 19, which are amino acids reported in the ligand-binding pocket of α5β120, 21. Similarly, Raman bands of αvβ3-bound cRGD-GNPs can be attributed to the amino acids close to αvβ3 binding site20, 21, including Thr (995 cm−1), Tyr (831, 1261 cm−1), Lys (1076, 1143 cm−1), Phe (1603 cm−1) and amino acid associated C-H bending (1290, 1452 cm−1)18, 19. Arg (980, 1323 cm−1), Asp (1251 cm−1) and Phe (1003 cm−1) bands18 are observed in SERS spectra of cRGD-GNPs. The intense broad peak at around 1562 cm−1 is attributable to amide carbonyl group vibrations and aromatic hydrogens19 and may also be associated with residual citrate. More peak assignments can be found in supporting information (see SI Table S2). The distinct SERS spectra of α5β1 and αvβ3, which arise from the differences in the molecules and their orientation in respective binding sites, suggest spectral signatures to differentiate these two integrin receptors.

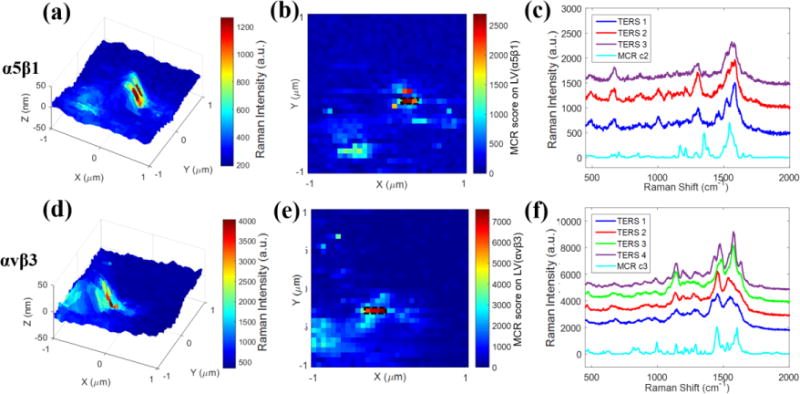

TERS spectra of the cRGD-GNPs bound to pure α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins were obtained by immobilizing the receptors onto glass slides through a silane-aldehyde coupling protocol22 (see SI Figure S3). Details of the immobilization procedure are provided in Materials and Methods section. The immobilized receptors were incubated with cRGD-GNPs. Unbound particles were removed by repeated rinsing before TERS measurements. 3-D TERS maps (Figures 2a, 2d) were generated using single-peak intensities at 1304 cm−1 (Ala) and 1452 cm−1 (C-H bending), showing the high intensity pixels are observed near the particles (height~50 nm). It was noticed that the high-intensity pixels appear not at the apex of the particle, but only toward one side at the ridge. This can be attributed to the asymmetric scattered electric field generated between TERS tip and the nanoparticle under radial polarization with the objective used8.

Figure 2.

TERS imaging of integrin α5β1 (a–c) and αvβ3 (d–f) immobilized on glass slides. The upper row are experiments for α5β1 and the lower row corresponds to αvβ3 receptors. (a, d) 3-D TERS mapping of generated from single peak intensity at (a) 1304 cm−1 and (d) 1452 cm−1. (b, e) 32×32 MCR score map generated from (b) LV(α5β1) and (e) LV(αvβ3). (c, f) Enhanced TERS spectra of (c) α5β1 and (f) αvβ3 extracted from the high intensity pixels (rectangular boxes) in (b) and (e). Scan area: 2×2 μm2. Step size: 62.5 nm per pixel.

The MCR model generated from the SERS data was applied to the TERS spectra in order to identify and compare the TERS signals with the pure components generated from SERS data (c1, c2, c3). Scores (s1, s2, s3) were generated from MCR analysis to represent the spectra composition in the pure components. We used two latent variables (LVs) to estimate the spectral contribution from α5β1 and αvβ3 as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Figures 2b and 2e show the score maps of LV(α5β1) and LV(αvβ3) generated from TERS data. The LV maps reflected the spectral contribution from each receptor type while TERS maps included the contributions of all components. As expected, there is strong agreement between the LV maps (Figures 2b, 2e) and TERS maps (Figures 2a, 2d) because each sample consisted of single protein receptor immobilized on the surface. TERS spectra at high intensity pixels (black boxes, Figures 2b and 2e) showed similarity to pure components from SERS spectra (Figures 2c, 2f). There are some slight differences (see SI, Table S2 for detail) in vibrational frequencies and intensities between the TERS and SERS spectra, as have been reported in several other TERS studies23, 24, which likely arise from differences in the arrangement between coupled plasmonic structures and small alterations in binding conformation upon receptor immobilization. However, the chemical characteristics of α5β1 and αvβ3 ligand-binding sites are still reflected in the TERS spectra, via binding of cRGD-GNPs. The similarity of the spectra strongly suggests the binding is a specific interaction.

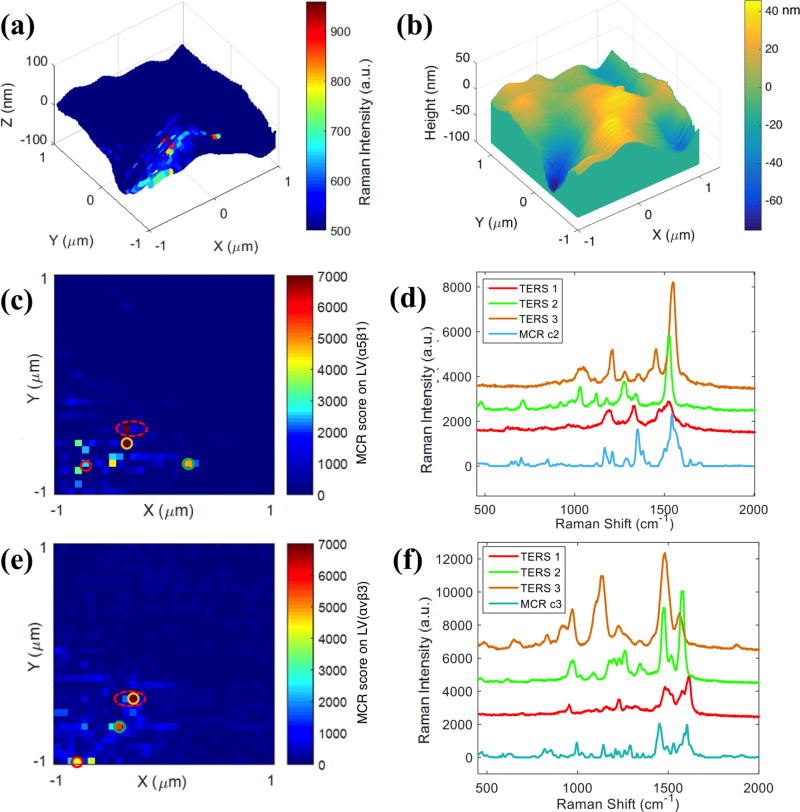

To assess the ability of our model to differentiate between receptors in intact cell membranes, the cRGD functionalized nanoparticles were incubated with SW480 colon cancer cells. The cells were fixed before TERS measurements. Figure 3a and 3b show a 3-D TERS maps where spectra obtained every 62.5 nm, the intensity at 1003 cm−1 is plotted onto the corresponding AFM topography map of a 2×2 μm area in a SW480 cell membrane. The area of the cell membrane imaged is identified by the characteristic dark-field scattering of the functionalized nanoparticle probe. The 1003 cm−1 band, attributed to phenylalanine residue from cRGD peptide, is used to identify regions with enhanced signals resulting from the tip-nanoparticle coupling. To evaluate the importance of tip-nanoparticle coupling, near-field TERS and far field SERS imaging of the same single SW480 cell were performed (see SI Figure S4). A far-field Raman map showed no observable signal (Figure S4d), confirming our earlier report9 that the nanoparticle alone is insufficient for detection under the experimental conditions (1mW power, 1s acquisition) used for TERS. Nevertheless, the TERS map shows enhanced signals at selected locations (Figure S4c), which are attributed to the formation of a tip-nanoparticle complex that produces greater signal enhancements. In addition, since the coupling enhancement between nanoparticles is highly distance-dependent25, only nanoparticles on the cell surface are able to generate enhanced TERS signals. SEM images of the cells show nanoparticles sparsely attached on the surface of the cell (see SI Figure S5). Typically the integrin receptors are highly expressed on human cancer cells, the relative low density of integrins recognized in our experiments (both TERS and SEM) is likely attributed to the combination of nanoparticle concentration and incubation time. In other experiments with longer incubations and higher concentrations, larger density of particles have been observed.12

Figure 3.

TERS measurements on SW480 cell. (a) 3-D TERS map constructed with single-peak intensity at 1003 cm−1. (b) AFM topography map of the same area as (a). (c, e) MCR score maps created from (c) LV(α5β1) and (e) LV(αvβ3). (d, f) Extracted spectra from circled pixels in (c) and (e). Scan area: 2×2 μm. Step size: 62.5 nm per pixel.

The TERS data obtained from the nanoparticles on the cell were analyzed with the MCR model and score maps were generated. Figures 3c and 3e show the LV(α5β1) and LV(αvβ3) maps generated from TERS imaging on the same cell. Spectra of various scoring levels (labeled with different color circles) were extracted and shown in Figures 3d and 3f. Comparing the observed spectra at each pixel with MCR components, shows similarities and differences. For example, minor peak shifts are observed and some new peaks appear (e.g. 1453 cm−1, purple spectrum in Figure 3d) in the TERS spectra. However, characteristic Raman bands of amino acids relevant to RGD binding for α5β1 (e.g. Ala/Leu: 1349 cm−1) and αvβ3 (e.g. Thr: 991 cm−1) are still observed. The general similarity between TERS and SERS spectra, and the appearance of characteristic peaks associated with respective ligand binding sites, provide confidence in the detection and differentiation between α5β1 and αvβ3 receptors in the same SW480 cell, despite some small variation in peak intensities and positions. It has been reported that colocalized α5β1 and αvβ3 subsequently translocate on cell membrane to regulate different mechanochemical steps of cell-matrix adhesion26. Here we noticed that two adjacent pixels with high levels of α5β1 and αvβ3 (red dashed circles in Figures 3c and 3e) were observed in the TERS maps, suggesting the colocalization of α5β1 and αvβ3 within ~60 nm range. In addition, the fact that exclusive spectral signatures are detected from co-localized integrin receptors α5β1 and αvβ3 indicates the TERS signal may arise from individual receptors. Further experiments are planned to investigate that possibility.

Discussion

Integrins α5β1 and αvβ3 both play important roles in cell adhesion and molecular connection to extracellular matrix through binding with fibronectins containing the RGD motif, though their specific roles in mediating cell adhesion are different. Investigations in cellular systems with α5β1 and αvβ3 co-expression have demonstrated that α5β1 integrins accomplish force generation and determine adhesion strength, whereas αvβ3 integrins mediate the structural adaptions to forces and cooperatively enable mechanotransduction26, 27. In addition, α5β1 and αv-class integrins are found to regulate a diverse array of cellular functions crucial to the initiation, progression and metastasis of solid tumors14. Because of this, integrins are appealing targets for cancer therapy, and due to the binding affinity and specificity of integrins to RGD peptides, RGD-based molecules are widely investigated as potential drugs for tumors. One example of the therapeutics is Cilengitide, a cyclo-RGD based drug molecule. It has been shown to selectively bind to and inhibit αv-class integrins28, 29. Preclinical studies in mice have shown that Cilengitide is able to demonstrate efficacious tumor regression30. However, in a recent Phase III clinical study, Cilengitide showed lack of efficacy to treat human brain cancer31. The plasmon-enhanced spectroscopy could provide chemical insight into the RGD-integrin binding structures, which may facilitate the process of drug discovery. The methodology developed here may provide an early stage screen to identify different receptors that bind a ligand. Here we have demonstrated differentiation between two related structures, suggesting the signature of other receptors could also be identified.

The detection of proteins covalently bound to the surface by this methodology also raises questions about the necessity of hotspots for enhanced Raman detection. Willets and colleagues have demonstrated super resolution single molecule imaging on nanoparticle aggregates that clearly shows the diffusion of molecules outside of the gap junction32. Schatz and colleagues have shown that the gap junction is not the sole location of enhanced field in a nanoparticle dimer; the outer endpoints of the nanoparticle dimer are also locations with enhanced field.33 Recently Baumberg and coworkers examined nanoparticles on gold thin films to assess the correlation between excitation frequency and enhanced Raman scattering34. In this paper, they concluded that the Raman signals and the maximum dark-field scattering did not arise from the same physical location. The results presented in this manuscript, that receptors on surfaces can be detected through the interaction of a TERS tip with a bound nanoparticle, support these observations and suggest that alternative mechanisms, perhaps chemical in nature, are responsible for the observed Raman enhancements. It is not possible for the protein to reside in the gap between the nanoparticle and the TERS tip in either the surface or cell experiments, yet the signals observed clearly are associated with the protein receptor. The selectivity observed in the intact membranes may also arise from this yet to be understood mechanism. Future experiments will explore the nature of these enhancements and their ability to assess protein-ligand binding.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have presented data to apply TERS technique for detection and differentiation of human integrin receptors in intact cells. By using cRGD peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticles as probes, we are able to obtain distinct TERS spectra of α5β1 and αvβ3 receptors, due to slight differences in their respective ligand binding sites. We have demonstrated the ability of TERS to chemically characterize the ligand-receptor recognition at molecular level in cells, showing its potential as a new method to provide chemical perspectives in molecular processes of membrane surface receptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the United States National Institutes of Health, award R01 GM109988.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available as noted in text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Characterization of cRGD-GNPs; supplementary figures S1–S5; supplementary tables S1 and S2.

References

- 1.Lee S, Mandic J, Van Vliet KJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9609–9614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702668104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao L, Chen Q, Wu Y, Qi X, Zhou A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848:1988–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietz MS, Fricke F, Kruger CL, Niemann HH, Heilemann M. Chemphyschem. 2014;15:671–676. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201300755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoichet BK. Nature. 2004;432:862–865. doi: 10.1038/nature03197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiles PL, Dieringer JA, Shah NC, Van Duyne RP. Annu Rev Anal Chem(Palo Alto Calif) 2008;1:601–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campion A, Kambhampati P. Chem Soc Rev. 1998;27:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter M, Hedegaard M, Deckert-Gaudig T, Lampen P, Deckert V. Small. 2011;7:209–214. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander KD, Schultz ZD. Anal Chem. 2012;84:7408–7414. doi: 10.1021/ac301739k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrier SL, Kownacki CM, Schultz ZD. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:2065–2067. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05059h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Schultz ZD. Analyst. 2013;138:3150–3157. doi: 10.1039/c3an36898j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Carrier SL, Park S, Schultz ZD. Faraday Discuss. 2015;178:221–235. doi: 10.1039/c4fd00190g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Schultz ZD. ChemPhysChem. 2014;15:3944–3949. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millard M, Odde S, Neamati N. Theranostics. 2011;1:154–188. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marelli UK, Rechenmacher F, Sobahi TR, Mas-Moruno C, Kessler H. Front Oncol. 2013;3:222. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer KM, Lambert PA, Hummon AB. Proteomics. 2012;12:1928–1937. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultz ZD, Stranick SJ, Levin IW. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9657–9663. doi: 10.1021/ac901789w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu G, Zhu X, Fan Q, Wan X. Spectrochim Acta A. 2011;78:1187–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Movasaghi Z, Rehman S, Rehman IU. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2007;42:493–541. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mould AP, Koper EJ, Byron A, Zahn G, Humphries MJ. Biochem J. 2009;424:179–189. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heckmann D, Meyer A, Marinelli L, Zahn G, Stragies R, Kessler H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:3571–3574. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patolsky F, Zheng G, Lieber CM. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1711–1724. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailo E, Deckert V. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:1658–1661. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowcher DP, Deckert-Gaudig T, Brewster VL, Ashton L, Deckert V, Goodacre R. Anal Chem. 2016;88:2105–2112. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stiles PL, Dieringer JA, Shah NC, Van Duyne RR. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2008;1:601–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roca-Cusachs P, Gauthier NC, Del Rio A, Sheetz MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16245–16250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902818106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiller HB, Hermann MR, Polleux J, Vignaud T, Zanivan S, Friedel CC, Sun Z, Raducanu A, Gottschalk KE, Thery M, Mann M, Fassler R. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:625–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodman SL, Holzemann G, Sulyok GA, Kessler H. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1045–1051. doi: 10.1021/jm0102598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nisato RE, Tille JC, Jonczyk A, Goodman SL, Pepper MS. Angiogenesis. 2003;6:105–119. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000011801.98187.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada S, Bu XY, Khankaldyyan V, Gonzales-Gomez I, McComb JG, Laug WE. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1304–12. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000245622.70344.BE. discussion 1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisele G, Wick A, Eisele AC, Clement PM, Tonn J, Tabatabai G, Ochsenbein A, Schlegel U, Neyns B, Krex D, Simon M, Nikkhah G, Picard M, Stupp R, Wick W, Weller M. J Neurooncol. 2014;117:141–145. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Titus EJ, Weber ML, Stranahan SM, Willets KA. Nano Lett. 2012;12:5103–5110. doi: 10.1021/nl3017779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao E, Schatz GC. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:357–366. doi: 10.1063/1.1629280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lombardi A, Demetriadou A, Weller L, Andrae P, Benz F, Chikkaraddy R, Aizpurua J, Baumberg JJ. ACS Photonics. 2016;3:471–477. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.5b00707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.