Abstract

Controlled endothelial delivery of SOD may alleviate abnormal local surplus of superoxide involved in ischemia-reperfusion, inflammation and other disease conditions. Targeting SOD to endothelial surface vs. intracellular compartments is desirable to prevent pathological effects of external vs. endogenous superoxide, respectively. Thus, SOD conjugated with antibodies to cell adhesion molecule PECAM (Ab/SOD) inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling mediated by endogenous superoxide produced in the endothelial endosomes in response to cytokines. Here we defined control of surface vs. endosomal delivery and effect of Ab/SOD, focusing on conjugate size and targeting to PECAM vs. ICAM. Ab/SOD enlargement from about 100 to 300 nm enhanced amount of cell-bound SOD and protection against extracellular superoxide. In contrast, enlargement inhibited endocytosis of Ab/SOD and diminished mitigation of inflammatory signaling of endothelial superoxide. In addition to size, shape is important: endocytosis of antibody-coated spheres was more effective than that of polymorphous antibody conjugates. Further, targeting to ICAM provides higher endocytic efficacy than targeting to PECAM. ICAM-targeted Ab/SOD more effectively mitigated inflammatory signaling by intracellular superoxide in vitro and in animal models, although total uptake was inferior to that of PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD. Therefore, both geometry and targeting features of Ab/SOD conjugates control delivery to cell surface vs. endosomes for optimal protection against extracellular vs. endosomal oxidative stress, respectively.

Keywords: intracellular delivery, endothelial cells, vascular immunotargeting, cell adhesion molecules, endocytosis

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

In pathological conditions including inflammation and ischemia-reperfusion, both insufficiency of antioxidants and/or surplus of reactive oxygen species (ROS, e.g., superoxide anion), lead to vascular oxidative stress, which further aggravates injury and ignites the vicious cycle of tissue damage [1, 2]. Design of drug delivery systems for antioxidants including polymeric and liposomal carriers, fusion proteins, antibody and other protein conjugates, nanozymes and other approaches is an active and promising area of current drug delivery research [3-5].

Endothelial cells represent the key therapeutic target for antioxidant interventions in these conditions [2]. Indeed, endothelial targeting of antioxidants provides potent protective effects in animal models of vascular oxidative stress unrivaled by untargeted enzymes [6-8]. However, better mechanistic understanding and design of delivery systems are necessary in order to convert these encouraging results into an approach providing tangible medical benefits.

Among other aspects, the spatial control of endothelial targeting of SOD at sub-cellular level is warranted. It has long been known that ROS released from activated leukocytes attack endothelium from the milieu [9]. More recently, it has been found, however, that ROS produced by endothelium itself in response to pathological stimuli play an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammation and ischemia-reperfusion [2, 10, 11]. In particular, cytokines activate NADPH-oxidase in endothelial endosomes to flux superoxide in the lumen of these vesicles and local intracellular surplus of this ROS ignites an "autocrine" signaling leading to pro-inflammatory endothelial changes [11-13].

SOD conjugated with PECAM antibody (Ab/SOD) enters endothelial endosomes and quenches superoxide, thereby intercepting this unusual pro-inflammatory pathway and conferring anti-inflammatory effects [14, 15]. However, the design parameters that favor surface retention vs endosomal delivery of Ab/SOD have not been defined. These distinct localizations would be preferential for protection against extracellular ROS attack vs endosomal ROS signaling, respectively.

Size and binding specificity are among the most influential parameters of design that modulate endosomal delivery of diverse drug delivery systems [16]. However, the role of these parameters in endothelial targeting, internalization and effect of Ab/SOD is not known. Accordingly, here we studied how size of Ab/SOD targeted to endothelial molecules PECAM and ICAM regulate intracellular delivery and effect of Ab/SOD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and cell cultures

Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD) from bovine erythrocytes is from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Succinimidyl-6-[biotinamido] hexanoate (NHS-LC-biotin), 4-[N-maleimidomethyl] cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC), N-succinimidyl-S-acetylthioacetate (SATA) were from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Anti-human PECAM monoclonal antibodies used were mAb 62. Anti-human ICAM monoclonal antibodies were R6.5 from ATCC (Manassas, VA; hybridoma R6-5-D6) and LB-2 from Santa-Cruz Biotech. (Dallas, TX). Anti-murine PECAM monoclonal antibodies were MEC13.3 (BD Parmingen, SanJose, CA). Anti-murine ICAM monoclonal antibodies were YN1 from ATCC. Anti-human VCAM-1 goat polyclonal antibodies were from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN; cat# BBA19), anti-mouse VCAM-1 goat polyclonal antibodies were from Santa-Cruz Biotech.; anti-actin antibody HRP-conjugated was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Ab/SOD conjugates were prepared via amino-chemistry as described earlier [15]. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) was from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Lipopolysaccharide (Escherichia coli O55:B5, γ-irradiated) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). FITC-labeled polystyrene microspheres (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 6.0 μm diameter) were purchased from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). SOD was radiolabeled with sodium iodide radioisotope Na125I (PerkinElmer; Wellesley, MA) using Iodogen.

Cell culture and treatment

Human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVEC; Lonza Walkersville, Walkersville, MD) were maintained in EGM-2 BulletKit medium (Lonza) with 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (GIBCO) in Falcon tissue culture flasks (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) precoated with 1% gelatin for 1 h. Cells were activated by addition of TNF for 4-5 h.

Conjugate preparation

Antibodies were conjugated with SOD using amino-chemistry as described [15]. Protected sulfhydryl groups were introduced in the molecule of antibody via primary amines using SATA at a molar ratio antibody:SATA 1:100 at room temperature for 30 min. Further sulfhydryl groups were de-protected using 50 mM hydroxylamine for 2 h. Maleimide groups, which specifically react towards SH-group, were introduce into enzyme molecule using hetero-bifunctional cross-linker SMCC. The reaction was performed at a molar ratio SOD:SMCC 1:20 for 1 h at room temperature. Preliminary experiments showed that at 1:1 Ab:SOD molar ratio the resulting conjugates did not reach 50 nm, probably due to small size of SOD molecule (31 kDa) compared to IgG molecule (150 kDa). To prepare a series of conjugates with different sizes the molar ratio between antibody and SOD were varied from 1:1.5 to 1:5. Conjugation reaction was performed during 1 h on ice. Unreacted components were removed using Spin Protein Columns (G-25 Sephadex, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) after a reaction is completed. The effective diameter of the obtained conjugates was measured by Dynamic light scattering (DLS) using Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK) or 90Plus Particle Sizer (Brookhaven Instruments Corp., NY, US). Achievable size of the particles was from 50 to 350 nm; larger particles tended to aggregate. Conjugates were complimented with 7% sucrose (final concentration) as cryoprotector, frozen, and stored at −80°C before use. Test conjugation was always done when new batch of either protein or cross-linker were used before preparation of stock conjugates to adjust experimental conditions. For binding studies SOD was radiolabeled with Na125I using Iodogen (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Conjugate fractionation

To differentiate the protective effects of ‘small’ vs. ‘large’ particles we fractionated the preparation of ~300-nm conjugates. Conjugates were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 g yielded the supernatant containing Ab/SOD with a narrower size distribution and smaller average size. The supernatant fraction was compared with total material in binding and functional assays.

Preparation of Ab/nanoparticles

FITC-labeled polystyrene microspheres (50, 100, 200, 500 nm and 6 μm) were coated with anti-PECAM or anti-ICAM using incubation at room temperature for 1 h as described elsewhere[17], centrifuged to remove unbound materials, then resuspended in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS and microsonicated for 20 s at low power. The effective particle size was controlled by dynamic light scattering using a BI-90 Plus particle size analyzer with BI-9000AT Digital autocorrelator (Brookhaven Instruments, Brookhaven, NY).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of conjugates

Conjugate preparations were applied on TEM grid (Formvar Film 200 mesh; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hartfield, PA) and subsequently stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. Images were taken using JEM-1010 Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA).

Binding of PECAM-targeted SOD to endothelial cells

Ab/SOD conjugates targeted to PECAM carrying 10 mol% of radiolabeled SOD were incubated with HUVEC at 37°C for 1 h, unbound materials were washed out and cells were lysed with lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 1.0 M NaOH). Bound radioactivity was measured using a Wallac 1470 Wizard™ gamma counter (Gaithersburg, MD).

Western blotting analysis

Cells in 24 well culture dishes were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 100 μl of sample buffer for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Cell proteins were subjected to 4-15 % gradient gel. Gels were transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore) and the membrane was blocked with 3% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T (100 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 % Tween 20) for 1 h followed by incubations with primary and secondary antibodies in the blocking solution. The blot was detected using ECL reagents (GE Healthcare).

Internalization studies

Cells were grown on microscope glass cover slips pre-coated with Fibronectin-like protein polymer (Sigma), treated with Ab/SOD conjugates, and fixed with ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. For internalization studies, cells were treated first with Alexa Fluor 594 labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and treated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG [17]. For studies of internalization of FITC-labeled polysterene beads fixed cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 594 labeled goat anti-mouse IgG. Samples were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen), and fluorescence images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U fluorescence microscope equipped with a Plan Apo 40X/1.0 Oil objective. Microscope controlling and image processing were carried out using Image-Pro Plus 4.5.1.27. Separate images were acquired in green and red fluorescence channels using Hamamatsu Orca-1 CCD camera. Images were merged and analyzed by the Image-Pro software as described earlier [18, 19]. Internalization percentage was calculated as a ratio of surface-bound particles (i.e. double Alexa Fluor 594/Alexa Fluor 488 labeled in case of immunoconjugates or double Alexa Fluor 594/FITC labeled in case of experiments with immunobeads) to total bound particles (i.e. Alexa Fluor 488 labeled for immunoconjugates or FITC labeled for immunobeads). All experiments were done in duplicates. At least six fields were analyzed for each experimental condition. The data were calculated as mean±SD.

Model of extracellular oxidative stress

Extracellular oxidative stress was induced by hypoxanthine-xanthine oxidase (HX-XO) as described earlier[20]. Confluent HUVEC were incubated in the presence of HX-XO for 20 min, washed and incubated with fresh HBSS for 5 h at 37°C. Cell death was analyzed by 51Cr release[20].

Biodistribution of anti-PECAM/AOE conjugates in vivo

Animal experiments were performed according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania. I125-SOD (10 mol%) was used to prepare I125-labeled Ab/SOD or IgG/SOD conjugates and were injected IV (10 μg of SOD) in normal C-57BL/65 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) via tail vein. After 1 h, the internal organs were harvested, rinsed with saline, blotted dry, and weighed. Tissue radioactivity in organs and 100-μl samples of blood was determined in a Wallac 1470 Wizard™ gamma counter. The percentage of injected dose in an organ (%ID) measures the total amount of antibody uptake in an organ, showing biodistribution and effectiveness of antibody uptake.

Endotoxemia model in mice

LPS was injected in C-57BL/65 mice via tail vein. Ab/SOD conjugates were injected intravenously via tail vein and LPS (50 μg/kg) was injected same route in 15 min. In 5 hours after LPS challenge lungs were perfused and harvested. VCAM expression was analyzed by Western blot.

Statistical analysis

Unless specified otherwise, the data have been calculated and presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Statistical difference among groups was determined by Student t-test and was accepted as significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of Ab/SOD size on endothelial binding, internalization and protection from intracellular vs. extracellular ROS

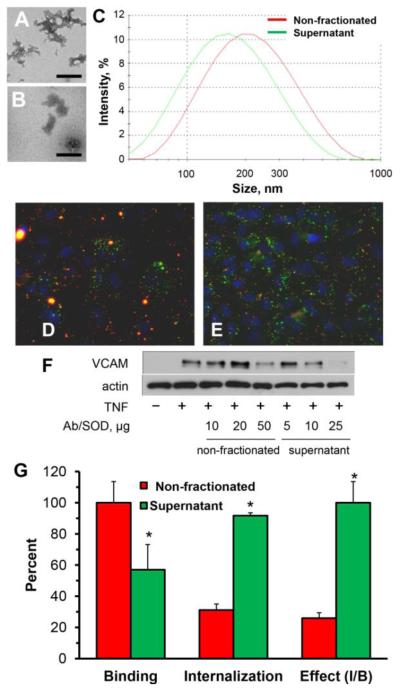

For initial inquiry of the role of size of SOD conjugates in its delivery and effect, we employed PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD conjugate that exerted anti-inflammatory effects including inhibition of cytokine-induced expression of endothelial VCAM-1 [14, 15]. Transmission electron microscopy and DLS showed that this Ab/SOD formulation represents a suspension of heterogeneous polymorphous species with mean size 250-350 nm and wide size distribution (Fig.1A-C). To remove large species, we centrifuged Ab/SOD for 10 min at 10,000 g, obtaining supernatant fraction of Ab/SOD with mean size decreased by approximately 50 nm (Fig. 1A-C).

Figure 1. Fractionation of PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD conjugates, endothelial uptake and effect of non-fractionated vs. fractionated conjugates.

(A-B). TEM of total unfractionated (A) and supernatant fraction (B) of PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD conjugate preparation with mean size of 250 nm. Scale bar is 200 nm. (C). Representative curves of size distribution of non-fractionated Ab/SOD (red) and supernatant fraction of Ab/SOD (green).. (D-E). Endothelial binding and internalization of non-fractionated Ab/SOD and supernatant fraction of Ab/SOD. Green and yellow colors indicate internalized and surface-bound conjugates, respectively. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (shown in blue). (F). Western blot analysis shows that supernatant fraction of Ab/SOD inhibits TNF-induced VCAM expression in HUVEC more effectively than non-fractionated conjugates. (G). Comparative summary of endothelial binding, internalization and relative inhibition of TNF-induced VCAM-1 expression calculated as inhibition rate to binding ratio (Effect, I/B; supernatant set as 100 %) for non-fractionated Ab/SOD vs. supernatant Ab/SOD (red and blue bars, respectively). *P<0.05 supernatant vs. non-fractionated.

Endothelial cells more effectively bound non-fractionated Ab/SOD (Fig. 1, G, left bar cluster), but internalized more effectively Ab/SOD from supernatant fraction (Fig.1D-G). To test functional effect of "small" vs. "large" Ab/SOD, endothelial cells were pre-incubated with non-fractionated vs. supernatant Ab/SOD, challenged with TNF and analyzed for VCAM-1 expression level. Results showed that supernatant fraction of Ab/SOD more effectively inhibited TNF-induced expression of VCAM-1 in endothelial cells than non-fractionated Ab/SOD (Fig.1F), despite the fact that the latter binds more effectively (Fig.1, panels D, E, and G). Results of this series suggested that: i) small Ab/SOD species enter endothelial cells and inhibit cytokine-induced pro-inflammatory activation more effectively than large counterparts; and, ii) sub-cellular localization of Ab/SOD is more important for this effect than total amount of cell-associated Ab/SOD.

To investigate this notion more precisely and minimize compounding effects of heterogeneity of size of Ab/SOD formulations, we synthesized a new series of Ab/SOD with different size. Varying Ab to SOD molar ratio we synthesized a series of PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD with mean sizes from about 50 nm to 300 nm. Fig. 2 shows typical set of Ab/SOD conjugates synthesized in one series, characterized by electron microscopy and DLS analysis.

Figure 2. Synthesis of Ab/SOD conjugates with controlled sizes.

(A). TEM (A) of representative Ab/SOD preparations of 53, 89 and 250 nm, respectively. Scale bar is 200 nm. (B). Size distribution as measured by DLS. (C). Representative curve of conjugate size dependence on molar ratio. Molar ration 1:1 produce the conjugates less than 30 nm and was not used in this study. See Methods for the details.

We systematically and quantitatively studied in independent experiments several series of size-controlled formulations of PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD conjugates containing 125I-labeled SOD prepared at different time spanning about a year. Comparing data of these series helps to appreciate the level of experimental accuracy and reproducibility, with rather trivial and insignificant variability in exact size and uptake values (Supplement Fig.S1). These experiments unequivocally indicated that endothelial binding increases, whereas the internalization concomitantly decreases with enlargement of Ab/SOD (Supplement Fig.S1 and Fig. 3A). Furthermore, in a good agreement with data of fractionation study shown in Fig.1, smaller Ab/SOD inhibited VCAM-1 expression caused by TNF equally or even more effectively vs. larger Ab/SOD (Fig. 3B). In a stark contrast, larger Ab/SOD conjugates conferred more effective protection vs. smaller Ab/SOD counterpart in a model of endothelial oxidative stress caused by extracellular ROS produced by xanthine oxidase from xanthine in the medium (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Comparative binding, internalization, and protective chracteristics of Ab/SOD conjugates of different sizes towards internal and external ROS.

(A). Effects of conjugate size on binding and internalization of Ab/SOD. Binding was measured using 125I-labeled SOD. Internalization was estimated by analysis of microscopic images. (B-C) Comparison of protection against internal vs. external ROS. Cells were preincubated with large or small Ab/SOD and treated with ROS generating by TNF treatment (internal ROS, B; representative experiment) or xanthine/xanthine oxidase system (external ROS, C). Ab/SOD size was 800 and 300 nm in xanthine/xanthine oxidase model and 300 and 200 nm in TNF model. Allo, allopurinol, xanthine oxidase inhibitor. Inhibition of VCAM expression in TNF-activated HUVEC was estimated by Western blot analysis. Cells were pretreated with 100 μg/ml of Ab/SOD of indicated size for 1 h before TNF treatment foe 5 h. VCAM expression was analyzed by Western blot (B, inset) and quantified. Cell viability of xanthine/xanthine oxidase treated cells was measured by 51Cr release assay. *P<0.05 allopurinol vs. untreated; # P<0.05 large vs. small.

Geometry differently modulates their endothelial internalization of particles targeted to PECAM vs. ICAM

These data indicated that: i) depending on ROS source, cellular localization of Ab/SOD is more important for alleviation of oxidative stress than total dose of cell-associated Ab/SOD; and, ii) size of Ab/SOD conjugates modulates their endothelial binding, localization and effect. Keeping in mind therapeutic implications of these findings and wishing to diversify potential utility, we further investigated endothelial uptake of Ab/SOD targeted to distinct CAMs, PECAM and ICAM.

First, we compared endothelial uptake of Ab/SOD via PECAM and ICAM. Data of a representative experiment revealed a common trend of reduction of internalization with enlargement of Ab/SOD targeted to either CAM in the size range from ~70 nm to ~300 nm (Fig. 4). This result agrees with findings of reverse proportionality of endothelial uptake and size of other antibody conjugates targeted to PECAM[19].

Figure 4. Endothelial internalization of Ab/SOD conjugates targeted to PECAM vs. ICAM by HUVEC.

The conjugates of different sizes were incubated with cells for 1 h. (A). Green and yellow colors are internalized and surface-bound particles, respectively. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (B). Quantification of the internalized fractions, mean±SD is shown.

Reproducible synthesis of protein conjugates with tightly controlled size is very challenging (note slightly variable sizes of Ab/SOD preparations in sets of experiments shown in Fig.3, 4 and Supplement Fig.S1). To reduce imprecision and extend size range, we incubated cells with antibody-coated fluorescent polymeric spheres (Ab/beads). This study showed that internalization of very small and very large PECAM-targeted Ab/beads (50 nm and 6 μm) was less effective than that of intermediate size particles, whereas internalization of ICAM-targeted Ab/beads was effective in the whole range (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Endothelial internalization of Ab/particles targeted to PECAM vs. ICAM by HUVEC.

Particles were incubated with cells for 1 h. (A). Green and yellow colors are internalized and surface-bound particles, respectively. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (B). Quantification of the internalized fractions, mean±SD is shown. *P<0.05 anti-PECAM vs. anti-ICAM.

Cargo moiety of targeted conjugates, i.e., SOD in Ab/SOD, may interfere with cellular responses to cell-associated particles. To exclude influence of content and method of synthesis of protein conjugates, we studied uptake of drug-free antibody conjugates of different sizes. In support of the data shown in Figures 4 and 5 we found that enlargement of drug-free ICAM-targeted antibody conjugates leads to inhibition of their internalization, while Ab/beads are effectively internalized (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Clustering of CAM by anti-CAM/NP.

(A) Internalization of polymorphous vs. spherical anti-ICAM/NP of various sizes. (B) EC were incubated with either FITC-labeled (green) spherical anti-ICAM/NP (beads, right) vs. polymorphous conjugates (left) of various sizes for 1 h at 37°C. ICAM was visualized after cell permeabilization using TR-labeled LB2 anti-ICAM antibody that binds to domain distinct of that of R6.5 antibody used for targeting (red). Notice continuous ICAM clusters enveloping both small and large spherical anti-ICAM/NP (yellow-reddish color). In contrast, only small polymorphous anti-ICAM conjugates are continuously surrounded by ICAM, while large conjugates form irregular clusters of ICAM. (C) Hypothesis of internalization control by anti-ICAM/NP geometry: discordant formation of CAM clusters by large polymorphous NP does not favor proper signaling, cytoskeleton rearrangements and plasmalemma zipping.

To define the role of shape in uptake of targeted particles, we visualized target molecule, ICAM. For this purpose we stained permeabilized endothelial cells after incubation with antibody conjugates or particles, using fluorescently labeled LB2 anti-ICAM antibody that binds to ICAM domain distinct of that for R6.5 antibody used for ICAM targeting. This study revealed that molecules of ICAM in the plasmalemma envelope continuously Ab/beads of either ~300-500 nm and 3.5 μm size, while ICAM enveloping of protein antibody conjugates is less regular for both respective sizes (Fig. 6B). This can be explained by irregular polymorphous shape of protein antibody conjugates (Fig. 1&2). Shape irregularity of protein conjugates generally increases with their size (Fig. 1&2), as well as does energy required to form a vesicular envelope and commit necessary endocytic machinery. In contrast, lateral motility of ICAM molecules and clusters in the plasmalemma and its enveloping capacity reduce with conjugate size. Due to these factors, large Ab/conjugates engage ICAM in an irregular manner and no continuous envelope is formed (Fig. 6B). It is conceivable that instead of a congruent envelope igniting orchestrated signaling for the CAM-endocytosis of large spherical Ab/beads, large polymorphous Ab/conjugates initiate an array of weak and discordant signals that do not result in endocytosis (Fig. 6C).

ICAM-targeted Ab/SOD exerts more potent anti-inflammatory effect vs. PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD

In addition to implications for mechanisms of cellular entry, data shown above imply that targeting to ICAM vs. PECAM ignites different versions of CAM-endocytosis. Accordingly, we tested anti-inflammatory effect of Ab/SOD targeted to these CAMs.

We started with in vivo experiments, to determine whether significant differences between ICAM vs. PECAM targeted Ab/SOD would warrant further investigations. In this series we found that intravenously injected ICAM-targeted Ab/SOD less effectively accumulates in the pulmonary vasculature than PECAM-targeted counterpart (Fig. 7A). This outcome squares well with reported higher binding capacity of PECAM vs. ICAM in the vasculature, confirmed in several in vivo studies using diverse probes, cargoes and carriers conjugated with antibodies to ICAM and PECAM. Notwithstanding, despite inferior endothelial delivery of ICAM-targeted Ab/SOD, it more effectively inhibited cytokine-induced VCAM-1 expression in the lungs than PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD conjugate (Fig. 7B). Taking into account the dose of Ab/SOD that accumulated in the lung, anti-inflammatory potency of ICAM targeted Ab/SOD was 3.5 folds higher than that of PECAM targeted counterpart (Fig. 7B, inset).

Figure 7. Comparison of Ab/SOD targeted to PECAM and ICAM and effects in vivo.

(A). Lung targeting of SOD conjugated with corresponding antibody. Distribution of Ab/125I-SOD in lung (blue) vs. blood (red) 1 h after intravenous injection in mice. The data are shown as mean ± S.D, n = 3. (B). Comparative protection against pulmonary VCAM expression in LPS-challenged animals. Ab/SOD (50 or 100 μg/mouse) were injected in tail vein followed by LPS challenge (50 μg/kg). After 5 h, lungs were harvested; VCAM expression was analyzed by Western blot and normalized per actin level, presented as a percentage of maximal LPS-induced VCAM level (analysis of ≥3 independent experiments); inset, Protection as normalized on lung uptake estimated for corresponding Ab/SOD (shown in panel A). n ≥ 3; mean±SD is shown. *P<0.05 anti-CAM vs. IgG; # P<0.05 anti-ICAM vs. anti-PECAM.

This outcome provided an impetus to investigate this aspect of Ab/SOD delivery further. Accordingly, we compared delivery and effect of ICAM and PECAM targeted Ab/SOD in vitro, since this model allows excluding systemic and other factors complicating interpretation of animal studies. First, in agreement with previous studies using other cargoes directed to CAMs in this model, we found that binding of Ab/SOD to PECAM markedly exceeds that to ICAM (Fig. 8A). However, at comparable doses, both conjugates provided similar suppression of cytokine-induced VCAM-1 expression, and ICAM-targeted Ab/SOD was more effective at rate-limiting range of low doses (Fig. 8B). Taking into account difference in the delivered dose, which was dramatically lower for ICAM-targeted conjugate, its anti-inflammatory efficacy is dramatically higher once it is normalized on total cell-associated fraction of conjugates (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. Comparison of Ab/SOD targeted to PECAM and ICAM and protection in vitro.

(A). Binding of Ab/SOD to HUVEC. Cells were incubated with Ab/125I-SOD for 1 h, washed and total cell-associated fraction was measured using gamma-counter. n ≥ 3; mean±SD is shown. (B). Comparative protection against TNF-induced increase of VCAM expression by HUVEC. Cells were pre-treated with Ab/SOD for 1 h and then activated by TNF for 4 h. VCAM expression was analyzed by Western blot and normalized per actin. (C). Protection as normalized on cell binding estimated for Ab/SOD (shown in panel A).

DISCUSSION

Endothelial cells do not internalize antibodies to PECAM and ICAM via canonical pathways, yet internalize particles carrying these antibodies clustering target molecules [18, 19] igniting CAM-endocytosis distinct from phagocytosis, pinocytosis, caveolar and clathrin endocytosis [18, 21]. Notwithstanding similarities of targeting to PECAM and ICAM, they have different structure, functions and localization in the plasmalemma and likely to mediate different versions of CAM-endocytosis. In fact, even binding to different PECAM epitopes leads to different patterns of carrier's uptake and traffic [22]. Further, CAM-endocytosis is modulated by cellular phenotype and hydrodynamic conditions [23].

The geometry of nanocarriers modulates sub-cellular addressing [24, 25]. In many instances, endocytosis increases with particle size until it exceeds the capacity of the vesicles providing internalization, but the optimal size may vary for different cell types, molecular targets, and vesicular pathways. For example, macrophages more rapidly take up and traffic to the lysosomes large vs. small particles (1-10 um vs. 30-300 nm) [26], whereas endothelial cells display an opposite trend [19, 24].

Previous studies addressed the role of Ab/SOD size and selection of anchoring site in blood clearance and organ distribution [15, 19]. However, the role of these design parameters in internalization and effect of Ab/SOD has not been addressed. This is a challenging task, taking into account difficulties associated with control of size and shape of multi-molecular protein conjugates that typically represent polymorphous heterogeneous species with wide size distribution [15, 19]. Ab/SOD used in previous studies was no exception, yet pilot studies on sedimentation-based separation of large and small conjugates did reveal interesting trends (Fig.1). Fine-tuning of the synthesis yielded accurately “calibrated” series of Ab/SOD (Fig.2 and 3), as well as sized drug-free antibody conjugates (Fig.6). Using precisely sized fluorescent polymeric spheres coated with antibodies (Ab/beads) further enhanced the accuracy and allowed to compare delivery of particles with different shapes (Fig.4-6). Taken together, results of experiments using these agents affirm the following conclusions.

Large conjugates deliver lots of cargo, likely due to heavy load and high-avidity multivalent binding (yet, non-specific uptake in the microvasculature increases with conjugate enlargement beyond 300-500 nm [27]). However, internalization diminishes with Ab/SOD enlargement. As result, small Ab/SOD conjugates quenching superoxide in the endosomes inhibit inflammatory cytokine signaling more effectively than large Ab/SOD species. In contrast, the latter are more effective in protecting endothelium from extracellular ROS, due to surface location, which would be preferable for quenching of ROS emanating from activated leukocytes. This outcome supports a general notion that sub-cellular localization of Ab/SOD is more important for its therapeutic effect than amount of cell-associated Ab/SOD.

This notion has been recapitulated in a separate series, comparing delivery and effect of Ab/SOD of similar size targeted to different cell adhesion molecules, ICAM and PECAM. Both in vivo and in vitro studies clearly demonstrated that despite lower delivered or cell-associated dose, Ab/SOD targeted to ICAM is more potent. Although this outcome (especially in vivo) may be due to multiple reasons, it is tempting to connect it with the data shown in Fig. 5, which imply that endothelial cells internalize ICAM-bound materials more effectively than PECAM-bound counterparts. This squares well with previously published data showing faster kinetics of endocytosis of particles of the same size via ICAM vs. PECAM [18]. Therefore, ICAM-medicated version of CAM-endocytosis seems to be more permissive than PECAM-directed counterpart.

Different localization in the plasmalemma, specific microenvironment, clustering, signaling and biomechanical features of ICAM and PECAM all may contribute to this interesting phenomenon. Our data indicate that ability of target molecules to envelope anchored particles is important for endocytosis, and that this function is more challenging for polymorphous protein conjugates than for spherical regular particles. This result agrees with findings that: i) endothelial cells internalize polymeric ICAM-targeted particles with size up to few microns; and, ii) uptake of ICAM-targeted particles is shape-dependent: spheres enter cells faster than disks [24]. In this context, we can conclude that size, shape and anchoring site all control endosomal targeting of Ab/SOD and ultimately its anti-inflammatory effects, which may find medical utility.

Endothelium is an important target in oxidative stress, especially in the lungs [28]. Antioxidants targeted to endothelial determinants PECAM and ICAM accumulate in the pulmonary vasculature and alleviate harmful effects of ROS [7, 28]. In particular, Ab/SOD alleviates endothelial abnormalities caused by angiotensin-II, VEGF and cytokines, which all are mediated by surplus intracellular of superoxide [7, 15]. In particular, cytokine-induced surplus superoxide in endosomes leads to vascular leakiness, expression of inducible adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 and other pro-inflammatory endothelial abnormalities. Endosomal delivery of Ab/SOD targeted to PECAM inhibits this pathological pathway and exerts anti-inflammatory effects [14, 15].

Superoxide is a short-live radical that poorly diffuses through cellular membranes and acts locally on a nanometer range [29]. Ideally, destination of antioxidants should correspond to the cellular localization of this ROS [2]. Indeed, present results show that rational design of Ab/SOD enables its preferential targeting to either endothelial surface or endosomes, thereby optimizing mechanistically specific protective effects against extracellular vs intracellular ROS, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Several parameters of design of multimolecular Ab/SOD conjugates control their endothelial delivery, preferential localization on cell surface vs. endosomes and mitigation of effects extracellular vs. intracellular superoxide. Conjugate enlargement from <100 to >300 nm enhanced amount of cell-bound SOD and protection against extracellular superoxide. However, enlargement of Ab/SOD inhibited endocytosis and diminished mitigation of inflammatory signaling of endothelial superoxide. In addition to size, shape is important: endocytosis of antibody-coated spheres was more effective than that of polymorphous antibody conjugates. Further, targeting to ICAM provides higher endocytic efficacy than targeting to PECAM. ICAM-targeted Ab/SOD more effectively mitigated inflammatory signaling by intracellular superoxide in vitro and in animal models, although total uptake was inferior to that of PECAM-targeted Ab/SOD. Therefore, both geometry and targeting features of Ab/SOD conjugates control delivery to cell surface vs. endosomes for optimal protection against extracellular vs. endosomal oxidative stress, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by RO1 HL073940 and HL087036 (VRM).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Additional Supplemental figures S1 and S2.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].den Hengst WA, Gielis JF, Lin JY, Van Schil PE, De Windt LJ, Moens AL. Lung ischemia-reperfusion injury: a molecular and clinical view on a complex pathophysiological process. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(5):H1283–1299. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00251.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thomas SR, Witting PK, Drummond GR. Redox control of endothelial function and dysfunction: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(10):1713–1765. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bagalkot V, Badgeley MA, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Rajagopalan S, Maiseyeu A. Hybrid nanoparticles improve targeting to inflammatory macrophages through phagocytic signals. J Control Release. 2015;217:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yun X, Maximov VD, Yu J, Zhu H, Vertegel AA, Kindy MS. Nanoparticles for targeted delivery of antioxidant enzymes to the brain after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(4):583–592. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kowalski PS, Kuninty PR, Bijlsma KT, Stuart MC, Leus NG, Ruiters MH, Molema G, Kamps JA. SAINT-liposome-polycation particles, a new carrier for improved delivery of siRNAs to inflamed endothelial cells. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;89:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Preissler G, Loehe F, Huff IV, Ebersberger U, Shuvaev VV, Bittmann I, Hermanns I, Kirkpatrick JC, Fischer K, Eichhorn ME, Winter H, Jauch KW, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR, Wiewrodt R. Targeted Endothelial Delivery of Nanosized Catalase Immunoconjugates Protects Lung Grafts Donated After Cardiac Death. Transplantation. 2011;92(4):380–387. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318226bc6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shuvaev VV, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Bhora F, Laude K, Cai H, Dikalov S, Arguiri E, Solomides CC, Albelda SM, Harrison DG, Muzykantov VR. Targeted detoxification of selected reactive oxygen species in the vascular endothelium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331(2):404–411. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Christofidou-Solomidou M, Scherpereel A, Wiewrodt R, Ng K, Sweitzer T, Arguiri E, Shuvaev V, Solomides CC, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR. PECAM-directed delivery of catalase to endothelium protects against pulmonary vascular oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285(2):L283–292. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00021.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP, Pober JS, Wick TM, Konkle BA, Schwartz BS, Barnathan ES, McCrae KR, Hug BA, Schmidt AM, Stern DM. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91(10):3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Laubach VE, Sharma AK. Mechanisms of lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000304. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Oakley FD, Abbott D, Li Q, Engelhardt J. Signaling Components of Redox Active Endosomes: The Redoxosomes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(6):1313–1333. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Frey RS, Ushio-Fukai M, Malik A. NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Signaling in Endothelial Cells: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(6):791–810. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li Q, Spencer NY, Oakley FD, Buettner GR, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal Nox2 facilitates redox-dependent induction of NF-kappaB by TNF-alpha. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(6):1249–1263. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shuvaev VV, Han J, Tliba S, Arguiri E, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Ramirez SH, Dykstra H, Persidsky Y, Atochin DN, Huang PL, Muzykantov VR. Anti-inflammatory effect of targeted delivery of SOD to endothelium: mechanism, synergism with NO donors and protective effects in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shuvaev VV, Han J, Yu KJ, Huang S, Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Nakada M, Muzykantov VR. PECAM-targeted delivery of SOD inhibits endothelial inflammatory response. FASEB J. 2011;25(1):348–357. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jordan C, Shuvaev VV, Bailey M, Muzykantov VR, Dziubla TD. The Role of Carrier Geometry in Overcoming Biological Barriers to Drug Delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2015 doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151216151856. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Muro S, Muzykantov VR, Murciano JC. Characterization of endothelial internalization and targeting of antibody-enzyme conjugates in cell cultures and in laboratory animals. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;283:21–36. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-813-7:021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Muro S, Wiewrodt R, Thomas A, Koniaris L, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR, Koval M. A novel endocytic pathway induced by clustering endothelial ICAM-1 or PECAM-1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 8):1599–1609. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wiewrodt R, Thomas AP, Cipelletti L, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Weitz DA, Feinstein SI, Schaffer D, Albelda SM, Koval M, Muzykantov VR. Size-dependent intracellular immunotargeting of therapeutic cargoes into endothelial cells. Blood. 2002;99(3):912–922. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shuvaev VV, Tliba S, Nakada M, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1-directed endothelial targeting of superoxide dismutase alleviates oxidative stress caused by either extracellular or intracellular superoxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323(2):450–457. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Garnacho C, Shuvaev V, Thomas A, McKenna L, Sun J, Koval M, Albelda S, Muzykantov V, Muro S. RhoA activation and actin reorganization involved in endothelial CAM-mediated endocytosis of anti-PECAM carriers: critical role for tyrosine 686 in the cytoplasmic tail of PECAM-1. Blood. 2008;111(6):3024–3033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Garnacho C, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR, Muro S. Differential intraendothelial delivery of polymer nanocarriers targeted to distinct PECAM-1 epitopes. J Control Release. 2008;130(3):226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Han J, Zern BJ, Shuvaev VV, Davies PF, Muro S, Muzykantov V. Acute and chronic shear stress differently regulate endothelial internalization of nanocarriers targeted to platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1. ACS Nano. 2012;6(10):8824–8836. doi: 10.1021/nn302687n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Muro S, Garnacho C, Champion JA, Leferovich J, Gajewski C, Schuchman EH, Mitragotri S, Muzykantov VR. Control of endothelial targeting and intracellular delivery of therapeutic enzymes by modulating the size and shape of ICAM-1-targeted carriers. Mol Ther. 2008;16(8):1450–1458. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Champion JA, Katare YK, Mitragotri S. Making polymeric micro- and nanoparticles of complex shapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(29):11901–11904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koval M, Preiter K, Adles C, Stahl PD, Steinberg TH. Size of IgG-opsonized particles determines macrophage response during internalization. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242(1):265–273. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shuvaev VV, Tliba S, Pick J, Arguiri E, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR. Modulation of endothelial targeting by size of antibody-antioxidant enzyme conjugates. J Control Release. 2011;149(3):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shuvaev VV, Muzykantov VR. Targeted modulation of reactive oxygen species in the vascular endothelium. J Control Release. 2011;153(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McCord JM. The evolution of free radicals and oxidative stress. Am J Med. 2000;108(8):652–659. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.