Highlights

-

•

Hepatic lesions have been infrequently reported in Alagille syndrome.

-

•

Most of them have been described as hepatocellular carcinoma.

-

•

Focal liver hyperplasia can also be a cause of focal lesion.

-

•

Magnetic resonance imaging features can reliably differentiate them.

Keywords: Alagille syndrome, Focal liver hyperplasia, Cirrhosis, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Alagille syndrome is a multisystem autosomal disorder. The main clinical features are chronic cholestasis due to paucity of intrahepatic bile ducts, which can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure.

Presentation of case

A 15 year-old girl with Alagille syndrome was referred for liver transplantation. She developed severe cirrhosis with refractory ascites. In the pre-transplant evaluation, imaging studies disclosed liver atrophy with a high density pseudotumor in the segment 4, raising the possibility of a hepatocellular carcinoma. However, behavior of the lesion was highly suggestive of focal compensatory hyperplasia surrounded by an atrophic liver. The patient was registered on the waiting list.

Discussion

Hepatic lesions have been described in Alagille syndrome in isolated case reports, and most of these have been reported to be hepatocellular carcinoma. However, they can be related to an area of focal compensatory hyperplasia in severe cirrhosis. These findings may also explain why progression of liver disease occurs only in 15% of patients.

Conclusion

The presence of a large hepatic nodule Alagille syndrome can be benign in these patients also predisposed to hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, cautious evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging study before liver transplantation is mandatory.

1. Introduction

Alagille syndrome, also known as arteriohepatic dysplasia, is a multisystem autosomal disorder due to defects in the Notch signaling pathway [1]. This syndrome can affect the liver, heart, skeleton, eyes, kidneys, and central nervous system. Liver involvement is one of the main clinical features, consisting of chronic cholestasis due to paucity of interlobular bile ducts [1]. Progressive liver disease, leading to cirrhosis occurs in approximately 15% of cases and may require liver transplantation (LT) [2]. These patients are at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, therefore early detection of liver tumors are critical in the management of this disease.

We describe the case of a patient with known Alagille syndrome who developed severe liver cirrhosis. Pre-transplant evaluation disclosed a nodular lesion in the segment 4 which corresponded to a focal hyperplasia in advanced cirrhosis.

2. Presentation of case

A 15 year-old girl was referred to our department for evaluation for LT. The diagnosis was suspected at the age of 2 months in the presence of jaundice due to cholestasis. Liver biopsy disclosed paucity of the intrahepatic bile ducts. A pulmonary stenosis was further highlighted and treated percutaneously. Moreover, the patient exhibited the typical dysmorphic facies with a prominent forehead, deep set eyes and pointed chin giving the face a triangular appearance associated with thoracic vertebral segmentation anomalies called “butterfly” vertebrae. In presence of these clinical features, the diagnosis of Alagille syndrome was ascertained. The patient’s mother did not have the same physical features. We did not disclose ophthalmic and renal anomalies. Pruritus was successfully treated with ursodeoxycolic acid and rifampicin, however, liver disease worsened gradually until decompensated cirrhosis at the age of 14 year-old and then refractory ascites.

At the time of evaluation, laboratory tests were as follow: elevated conjugated bilirubin = 290 μmol/l (normal value <5 μmol/l) and gammaglutamyl transpeptidase = 100 IU/l (normal: 30 IU/l), decreased prothrombin time = 48%, albumin = 30 g/l and platelets count = 67,000/mm3. Her Child-Pugh score was C 11 and Meld score 25.

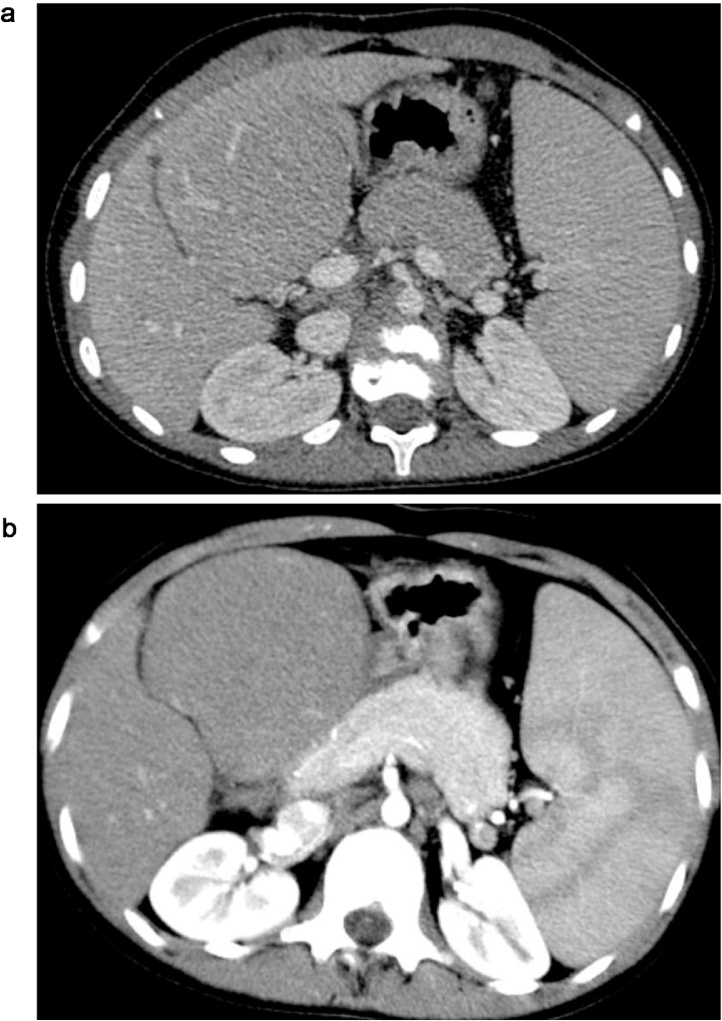

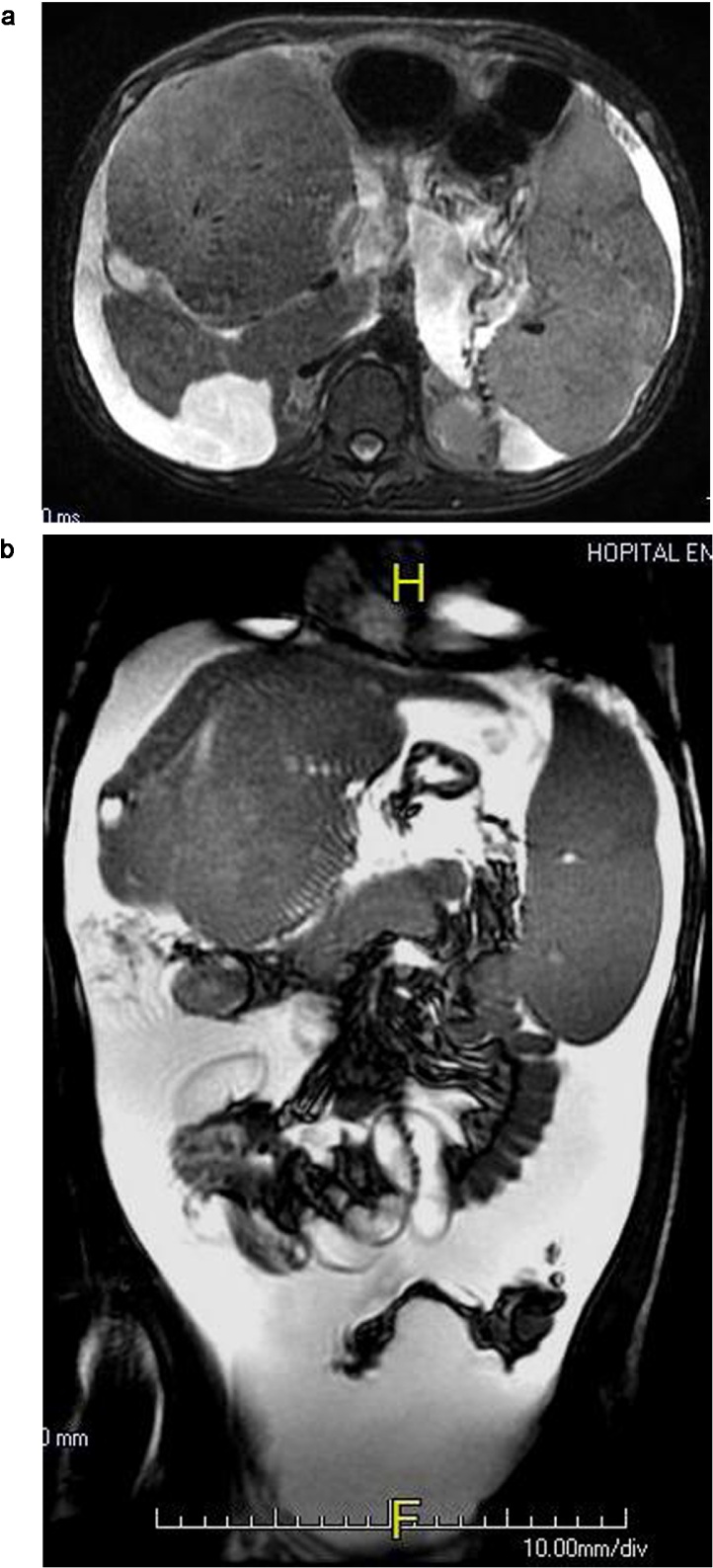

Liver ultra sound disclosed a large mass of the segment 4 of the liver, nodular in shape, isoechoic to the parenchymal liver (Fig. 1). The patient underwent a CT scan that revealed an important hypertrophy of the segment 4 of the liver having a tumoral appearance isodense to the liver on unenhanced and enhanced CT (Fig. 2a and b). The contrast enhancing CT imaging showed normal hepatic vasculature coursing through the lesion. The remaining liver segments were atrophic. CT scan showed also portal hypertension changes such as splenomegaly and venous collateral vessels. MRI, performed several months later, demonstrated that the mass-like segment 4 was increased in size and appeared isointense on T2 weighted images (Fig. 3a). The left liver lobe was deeply hypotrophic (Fig. 3b). On enhanced MRI with gadolinium agents, the pseudotumorous lesion was slightly hyperintense on arterial phase (Fig. 4) and iso-intense on portal one (Fig. 5). MRI showed also splenic necrotic foci areas and ascitis.

Fig. 1.

Liver ultrasonogram; large mass of the segment 4 isoechoic to the parenchyma.

Fig. 2.

Enhanced CT scan axial images (2a: arterial phase 2b: portal phase).

Pseudonodular hypertrophy of the segment 4 of the liver isointense. Normal vasculature of the liver is showed through the mass.

Fig. 3.

(a) T2 weigthed MRI axial image; a mass-like segment 4 of the liver isointense to the parenchyma. (b) T2 weighted MRI coronal image; important hypotrophic left liver lobe.

Fig. 4.

Arterial phase enhanced MRI; the pseudomass is slightly enhanced.

Fig. 5.

Portal phase enhanced MRI; the pseudomass is isointense. Ascitis and necrotic foci of spleen are present.

Alpha foeto protein level was 1.5 ng/ml (normal range) and the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was ruled out. Liver biopsy was avoided because of haemostasis disorders and ascites, especially as transjugular route was not available. In view of these findings, a focal compensatory hyperplasia surrounded by an atrophic liver was the most likely. Therefore, she was listed for LT. Liver ultrasound performed 1 year later demonstrated the same findings, without any change in the characteristic of the lesion (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Liver ultrasonogram one year later: stable appearance of the mass.

3. Discussion

This is a case of Alagille syndrome who developed severe cirrhosis with a pseudotumorous focal liver hyperplasia. Cross sectional study were helpful in characterizing this unusual lesion.

Alagille syndrome is a complex and rare autosomal dominant disorder [1]. Early cases were essentially ascertained through neonatal liver disease, as in our case.

The diagnosis is essentially clinical, dominated by chronic cholestasis and congenital heart disease. Classic criteria, based on the 5 main systems involved were established: cholestasis due to bile paucity, congenital heart disease (most commonly peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis), the face (mild but recognizable dysmorphic features), the skeleton (most commonly butterfly vertebrae), and the eye (most commonly posterior embryotoxon) [3]. It was held that the diagnosis is sustainable if bile duct paucity was accompanied by 3 of the 5 main criteria. Nervertheless, since the introduction of genetic testing, a wide variety of clinical features are now recognized [1]. In our case, genetic investigation was not available in our country, and the clinical features made the diagnosis of Alagille syndrome confident.

The prognosis of the syndrome is related to liver disease and congenital heart defects. Therapy is generally focused on these 2 organs.

Concerning the liver, paucity of interlobular bile ducts appears to develop through infancy and is considered as a key feature, reported in 80–90% in large series [1]. Though, progression does not always occur and deterioration of liver function and development of cirrhosis is reported in only 12% of patients [4]. Among them, approximately 20% will require LT either for hepatic failure or refractory pruritus [4]. Moreover, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has already been described during Alagille syndrome, therefore, a cautious evaluation before LT is mandatory [5], [6], [7], [8].

In this report, the patient was referred for LT because of refractory ascites while pruritus was moderate. The nodular lesion seen on imaging raised the possibility of a HCC, contraindicating LT. Previous reports have described nodular lesions in the liver associated with Alagille syndrome; they include hepatocellular carcinoma, hamartous nodule and regenerating nodules [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. In 3 cases, focal hyperplasia in advanced cirrhosis has been described [4], [11], [12]. In the first case, the lesion was in the caudate lobe, mimicking a tumor at ultrasonography [11]. At laparotomy, the caudate lobe had a pseudotumoral appearance, but at biopsy the liver parenchyma was preserved, while samples from the right and left lobes showed an absence of intrahepatic biliay ducts. The diagnosis of Alagille syndrome with areas free of hypoplasia of the intrahepatic biliary duct was the more likely. In the second case, the patient was referred for LT because of severe cirrhosis associated with Alagille syndrome [4]. He had a high density nodular lesion in the medial right lobe of the liver at CT scan. Radionuclides imaging studies showed severe hepatobiliary dysfunction with an area of increased focal uptake in the liver. Pathological evaluation at transplantation revealed that the focal uptake was an area of focal compensatory hyperplasia in a background of severe biliary cirrhosis [4]. In the last and more recent case, during pre-transplantation evaluation, CT and MRI revealed a large hepatic lesion with multiple small nodular lesions [12]. These latter were considered as hepatic nodular hyperplasia as large vessels running through the lesion were demonstrated [12].

Our case is similar to these previous reports; despite the lack of a pathologic study, HCC was ruled out, consequently, LT was not contra-indicated. Actually, liver biopsy was not practiced because the patient had ascites and coagulation disorders and the transjugular route was not available. These 3 previous reported cases allowed us to exclude a lesion contraindicating LT using only cross sectional imaging. Moreover, stability of the lesion during the follow-up ultrasound was an argument in favour of benignity.

The possibility of area free of hypoplasia of the intrahepatic biliary ducts may explain why progression of liver disease in Alagille syndrome does not always occur, moreover, a small proportion of patients have no manifestation of liver disease.

On the other hand, etiology of liver nodules in Alagille syndrome may encounter difficulties, and knowledge of this entity is important as these patients are also predisposed to HCC. The first reports used pathology and radionuclides imaging to confirm the diagnosis. We believe that after this case, MRI and CT scan may be enough to confirm the diagnosis.

4. Conclusion

Liver nodule in Alagille syndrome may be related to an area of focal compensatory hyperplasia in severe cirrhosis, therefore, cautious evaluation before liver transplantation is mandatory in these patients also predisposed to HCC. These findings may also explain why progression of liver disease occurs does not occur in all patients.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

No sources have funded our case.

Ethical approval

This case report does not require any ethical approval. All the figures are anonymized.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Rym Ennaifer: study concept and design, drafting the manuscript, acquisition of the data.

Leila Ben Farhat: analysis and interpretation of imaging studies.

Myriam Cheikh: analysis and interpretation of the data.

Ines marzouk: analysis and interpretation of imaging studies.

Hayfa Romdhane: analysis and interpretation.

Najet Belhadj: critical revision of the manuscript.

Guarantor

Dr. Ennaifer Rym.

References

- 1.Turnpenny P.D., Ellard S. Alagille syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;20:251–257. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alagille D., Estrada A., Hadchouel M., Gautier M., Odièvre M., Dommergues J.P. Syndromic paucity of interlobular bile ducts. J. Pediatr. 1987;110:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emerick K.M., Rand E.B., Goldmuntz E., Krantz I.D., Spinner N.B., Piccoli D.A. Features of Alagille syndrome in 92 patients: frequency and relation to prognosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:822–829. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torizuka T., Tamaki N., Fujita T., Yonekura Y., Uemoto S., Tanaka K. Focal liver hyperplasia in Alagille syndrome: assessment with hepatoreceptor and hepatobiliary imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 1996;37:1365–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams P.C. Hepatocellular carcinoma associated with arteriohepatic dysplasia. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1986;31:438–442. doi: 10.1007/BF01311683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauffmann S.S., Wood R.P., Shaw B.W., Markin R.S., Gridelli B., Vanderhoof J.A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a child with Alagille syndrome. AJDC. 1987;141:698–700. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460060114050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai S., Gurakar A., Anders R., Lam-Himlin D., Boitnott J., Pawlik T.M. Management of large hepatocellular carcinoma in adult patients with Alagille syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010;55:3052–3058. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim B., Park S.H., Yang H.R., Seo J.K., Kim W.S., Chi J.G. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurring in Alagille syndrome. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2005;201:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishikawa A., Mori H., Takahashi M., Ojima A., Shimokawa K., Furuta T. Allagile’s syndrome: a case with hamartomatous nodule of the liver. Acta Pathol. Jpn. 1987;37:1319–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syed M.A., Khalili K., Guindi M. Regenerating nodules in arteriohepatic syndrome: a case report. Br. J. Radiol. 2008;81:79–83. doi: 10.1259/bjr/63424939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuset E., Ribera J.M., Domenech E., Vaquero M., Oller B., Armengol M. Pseudotumorous hyperplasia of the caudate lobe of the liver in a patient with Alagille syndrome. Med. Clin. 1995;104:420–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tajima T., Honda H., Yanaga K., Kuroiwa T., Yoshimitsu K., Irie H. Hepatic nodular hyperplasia in a boy with Alagille syndrome: CT ans MR appearances. Pediatr. Radiol. 2001;31:584–588. doi: 10.1007/s002470100510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]