Abstract

AIM

To investigate the signal transduction mechanism of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) mediated- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression and retinal neovascularization (RNV) in oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) model.

METHODS

C57BL/6J mice were divided into four groups: control group, OIR group, OIR control group (phosphate-buffered saline by intravitreal injection) and treated group [tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) by intravitreal injection]. OIR model was established in C57BL/6J mice exposed to 75%±2% oxygen for 5d. mRNA level and protein expression of MMP-9, TIMP-1 and VEGF were measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting, and located by immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS

Levels of MMP-9 and VEGF in retina were significantly increased in animals with OIR and OIR control group. Levels of TIMP-1 in retina was significantly reduced in animals with OIR and OIR control group. Furthermore, a significant correlation was found between MMP-9 and VEGF. Intravitreal injection of TIMP-1 significantly reduced MMP-9 and VEGF expression of the OIR mouse model (all P<0.05).

CONCLUSION

These results demonstrate that MMP-9-mediated up-regulation of VEGF promotes RNV in retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). TIMP-1 may be a potential target for the prevention and treatment of ROP.

Keywords: retinal neovascularization, matrix metalloproteinase-9, vascular endothelial growth factor, oxygen-induced retinopathy

INTRODUCTION

Retinal neovascularization (RNV) causes loss of vision in most of retinal vascular diseases, including retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), diabetic retinopathy (DR) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD)[1]–[3]. Research showed that the production of ocular derived growth factors and cell adhesion molecules induce RNV, yet the complex interactions are not clear[1],[4]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent enzymes, and MMP-9 is the most frequently investigated MMPs in the brain and eye because it is relatively easy to be detected[5]–[6]. In particular, MMP-9 promotes endothelial cell migration, survival, and tubule formation[7]. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) is inhibitor of MMP-9, and the imbalances of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 cause excessive degradation of extracellular matrix[8]. In addition to stimulating angiogenesis[9], MMP-9/TIMP-1 is implicated in ischemia-induced RNV[10]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an important factor to stimulate the proliferation of endothelial cell and mediate RNV of ROP[11]–[12], whereas the correlation of MMP-9 and VEGF in ROP have largely remained elusive. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate MMP-9-VEGF signaling pathway in ROP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Groups

Oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mice model was constructed according to the protocol of Smith et al[13]. Animal experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by Animal Experimental Committee of China Medical University (Liaoning Province, China). In brief, C57BL/6J mice were placed in the hyperoxia chamber set at 75%±2% oxygen from 7 to 12d then placed in the normal air from 12d to 17d. They were maintained under conditions of standard lighting (a 12-hour light-dark cycle) and temperature (68°F).

Mice were randomly divided into control group (in normal air), OIR group, OIR control group and treated group (n=60/group). The treated or OIR control group were treated with 1 µL (500 ng/µL) of TIMP-1 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by vitreous cavity injection, and were moved to normal air at 12d. Four groups of mice were sacrificed at P17 to collect retinas.

Histologic Quantification of Preretinal Neovascularization

Sagittally cutted the whole eyes into serial sections (6 µm) then stained with H&E[14], dehydrated, vitrified, mounted, observed and imaged using a light microscope. Blindly grouped three reviewers to count the cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded 6 µm eye tissue sections were performed by immunohistochemical analysis, treated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against mouse MMP-9, TIMP-1 and VEGF (1:100 dilution; Boster Bioengineering Co., Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) at 4°C. PBS instead of the primary antibody. Images were observed using a light microscope.

Western Blot

Protein in each samples was extracted with lysis buffer. Equal amounts of samples were loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, electrophoretically separated and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes using standard procedures. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-MMP-9 polyclonal antibody, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; or rabbit anti-TIMP-1, VEGF polyclonal antibody, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight, then incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies at 37°C for 45min. Signals were detected using a chemiluminescence detection system (Technew Tech. Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Real-time Reverse Transcription-polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

The samples' RNA were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reverse transcription into cDNA with a reverse transcriptase kit TAKARA 047A according to the protocols. Primers were designed and purchased from Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a normalizing controlled. The sequence of primers is shown in Table 1. Calculated the 2−ΔΔCt to perform the relative quantification of the gene expression[15].

Table 1. Primers for real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Product length (bp) | Temperature (°C) | |

| GAPDH | Forward | CCC ATC TAT GAG GGT TAC GC | 150 | 55 |

| Reverse | TTT AAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC | |||

| MMP-9 | Forward | GGA GAC CTG AGA ACC AAT CTC | 277 | 55 |

| Reverse | TCC AAT AGG TGA TGT CGT | |||

| TIMP-1 | Forward | CCT TCT GCA ATT CCG ACC TC | 534 | 55 |

| Reverse | CGG GCA GGA TTC AGG CTA T | |||

| VEGF | Forward | CCC GAC AGG GAA GAC AAT | 131 | 55 |

| Reverse | TCT GGA AGT GAG CCA ACG | |||

Statistical Analysis

Resulting data was statistically analyzed using variance (ANOVA) by SPSS15.0 software, with P<0.05 being considered to be significant.

RESULTS

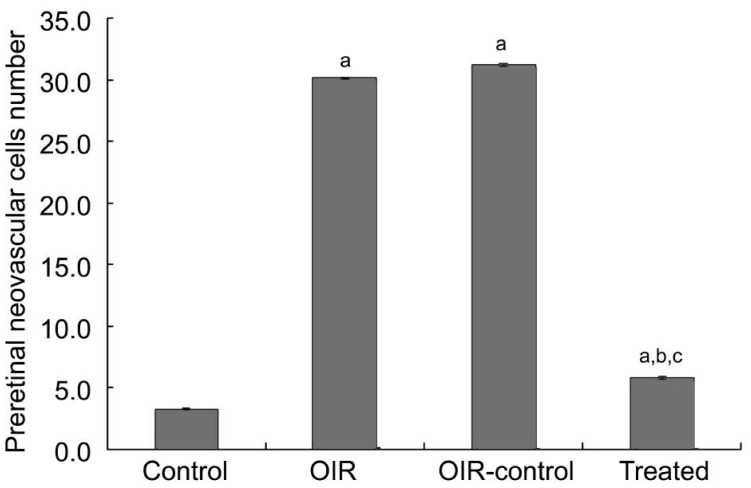

Quantitative Assessment of Retinal Neovascularization

There was an average of 30.24±0.83 and 31.13±1.21 nuclei per slice in the OIR and OIR control group compared to 3.27±0.65 in the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 1). The number of preretinal neovascular cells in the treated group (5.72±1.10) decreased significantly compared with the OIR and OIR control group (P<0.05). It proved that there is an inhibitory effect on RNV in the treated group.

Figure 1. Preretinal neovascular cells of P17 mice were counted.

aP<0.05 vs the control group, bP<0.05 vs the OIR group, cP<0.05 vs the OIR control group.

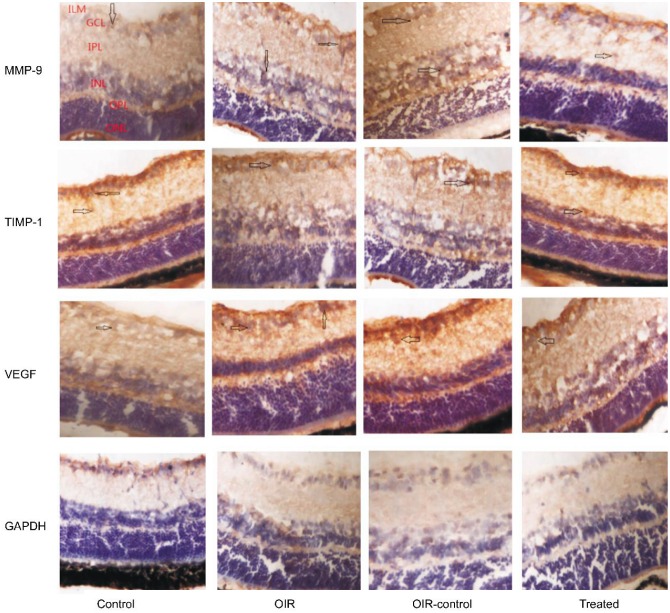

Matrix Metalloproteinase-9-vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling Pathway Expression by Immunohistochemistry

Figure 2 showed that MMP-9 and VEGF expression was weakly detected only in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL) of the control group. Whereas in the control group, TIMP-1 expression was strongly detected in the GCL, IPL and inner nuclear layer (INL). In the OIR and OIR control group, MMP-9 and VEGF expression were strongly detected in the GCL, IPL, INL, outer plexiform layer (OPL) and neovascularization breaking through the internal limiting membrane (ILM). Whereas in the OIR and OIR control group, TIMP-1 expression was weakly detected only in the GCL, IPL, INL and neovascularization breaking through the ILM. However, MMP-9 and VEGF showed low-level expression in the GCL, IPL and neovascularization breaking through the ILM of the treated group compared with the OIR and OIR control group. TIMP-1 showed high-level expression in the GCL, IPL, INL and neovascularization breaking through the ILM of the treated group compared with the OIR and OIR control group. The results proved that hypoxia induced the expression of MMP-9 and VEGF, and TIMP-1 could inhibite the expression of MMP-9 and VEGF.

Figure 2. MMP-9-VEGF signaling pathway in OIR mice model.

Protein expression of MMP-9, TIMP-1, and VEGF was determined by immunohistochemistry (magnification: 400×). The arrows indicate MMP-9-, TIMP-1- or VEGF-positive cells.

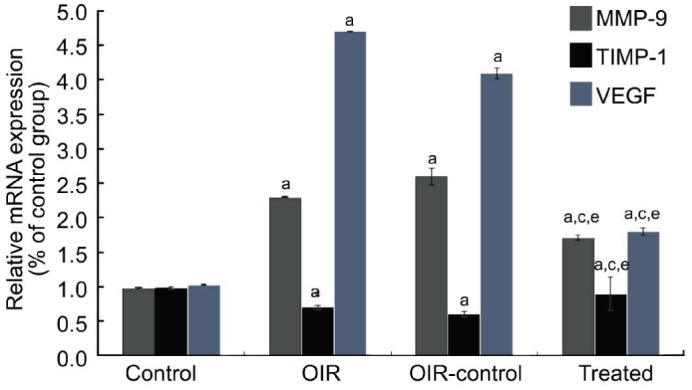

Inhibitory Effect of Tissue Inhibitors of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1

Real-time reverse transcription- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to determine MMP-9, TIMP-1 and VEGF mRNA expression in retina samples. MMP-9 (+135% and +166%) and VEGF (+358% and +299%) expression were increased in the OIR and OIR control group compared with the control group (all P<0.05) (Figure 3). TIMP-1 (-28.5% and -38.7%) expression was decreased in the OIR and OIR control group compared with the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 3). Compared with the OIR control group, the treated group decreased MMP-9 and VEGF mRNA expression (-34.6% and -56.1%, respectively, all P<0.05) and increased TIMP-1 mRNA expression (+50%, P<0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. TIMP-1 inhibited RNV through the inhibition of the MMP-9-VEGF signaling in OIR mice model.

MMP-9, TIMP-1 and VEGF were determined by real-time RT-PCR (n=9). aP<0.05 vs the control group, cP<0.05 vs the OIR group, eP<0.05 vs the OIR control group.

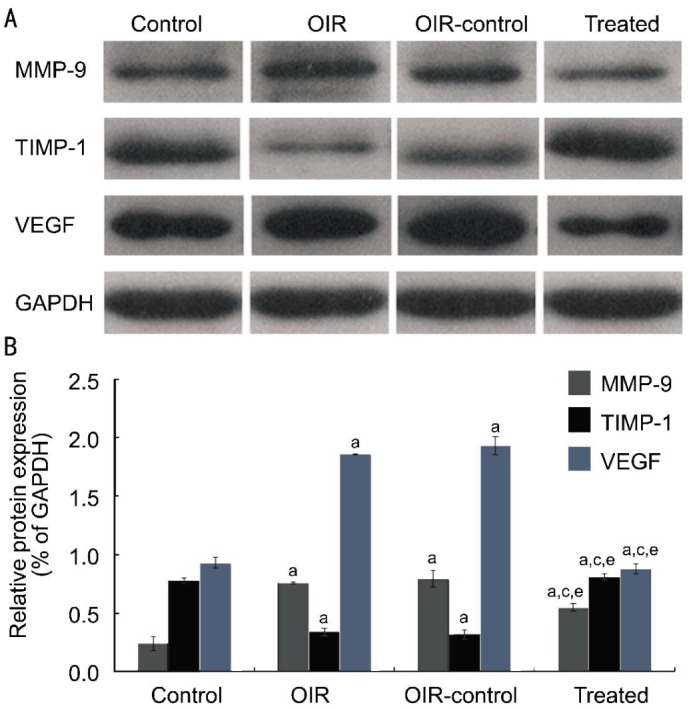

Western blot revealed similar results in retina samples (Figure 4). MMP-9 (+217% and +231%) and VEGF (+100% and +106%) protein expressions were increased in the OIR and OIR control group compared with the control group (all P<0.05) (Figure 4B). TIMP-1 (-56.4% and -59.1%) protein expression was decreased in the OIR and OIR control group compared with the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 4B). Compared with the OIR control group, the treated group decreased MMP-9 and VEGF protein expression (-30.7% and -54.4%, respectively, all P<0.05) and increased TIMP-1 protein expression (+154%, P<0.05) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. TIMP-1 inhibited RNV through the inhibition of the MMP-9-VEGF signaling in OIR mice model.

MMP-9, TIMP-1 and VEGF were determined by western blot (n=9). A: Western blot assay for protein expression; B: Statistical analysis. aP<0.05 vs the control group, cP<0.05 vs the OIR group, eP<0.05 vs the OIR control group.

DISCUSSION

RNV is an important pathological event and a main cause of blindness. Recent studies have demonstrated that retinal laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy and transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT) were the effective methods for the treatment of RNV. However, these methods may affect visual function. At present, intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF drug (bevacizumab or ranibizumab) has become an increasingly popular therapy for ROP[16]–[18]. Angiogenesis is a multistep process, and many ways could interfere with its progression[19]. Consequently, the focus of our research is to clarify the molecular mechanisms of RNV.

MMPs are important in the development of the central nervous system and retina. Several research groups have examined high expression of MMPs in RNV. Recent research has shown that MMPs have dual role in the development of DR; in the early stages of the disease (pre-neovascularization), MMP-2 and MMP-9 facilitate the apoptosis of retinal capillary cells, possibly via damaging the mitochondria, and in the later phase, they help in neovascularization[9]. Although higher levels of MMPs were observed in the vitreous of patients with proliferative retinopathy over two decades ago, their role in the development of this blinding disease has remained unclear[20]. Das et al[21] reported that human diabetic epiretinal neovascular membranes contain high levels of MMP-9 and urokinase. Beránek et al[22] reported increased MMP-9 expression in the retinas of proliferative DR. However, there are few reports regarding the interaction between MMP-9 and VEGF on RNV in the OIR model. Based on these findings, the present study aimed to determine whether the expression of VEGF was regulated by MMP-9 on RNV.

We found that increased MMP-9 expression (protein: +217%; mRNA: +135%) contributed to the increased level VEGF (protein: +100%; mRNA: +358%) and RNV in OIR. In addition, TIMP-1(inhibitor of MMP-9) significantly inhibited RNV by reducing the expression of VEGF. Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that the expression levels of MMP-9 and VEGF and RNV were prevented by intravitreal injection of TIMP-1. These results suggested that MMP-9 depletion could reduce VEGF production, which play the role of anti-angiogenesis. We also found that the anti-angiogenic effect of TIMP-1 derived from the reduction of VEGF. Thus, these results strongly suggest that MMP-9 plays an important role in OIR retinas. Furthermore, there was no inflammatory reaction and cellular toxicity in the treated group, and the generation of normal retinal blood vessels was not affected, which shows that intravitreal injection of TIMP-1 may be safe and effective for preventing RNV in the OIR model. MMP-9-targeted interventions may have an effective therapeutic effect on ROP.

Acknowledgments

Foundations: Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81371045); Science and Technology Project of Shenyang City, China (No.F13-220-9-37).

Conflicts of Interest: Di Y, None; Nie QZ, None; Chen XL, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lamoke F, Labazi M, Montemari A, Parisi G, Varano M, Bartoli M. Trans-Chalcone prevents VEGF expression and retinal neovascularization in the ischemic retina. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93(4):350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damico FM. Angiogenesis and retinal diseases. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70(3):547–553. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492007000300030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Y, Zhang Y, Yang H, Wang A, Chen X. The mechanism of CCN1-enhanced retinal neovascularization in oxygen-induced retinopathy through PI3K/Akt-VEGF signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2463–2473. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S79782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim WT, Suh ES. Retinal protective effects of resveratrol via modulation of nitric oxide synthase on oxygen-induced retinopathy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2010;24(2):108–118. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2010.24.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egashira Y, Zhao H, Hua Y, Keep RF, Xi G. White matter injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage: role of blood-brain barrier disruption and matrix metalloproteinase-9. Stroke. 2015;46(10):2909–2915. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Setz C, Brand Y, Radojevic V, Hanusek C, Mullen PJ, Levano S, Listyo A, Bodmer D. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in the cochlea: expression and activity after aminoglycoside exposition. Neuroscience. 2011;181:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitajima K, Koike J, Nozawa S, Yoshiike M, Takagi M, Chikaraishi T. Irreversible immunoexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in proximal tubular epithelium of renal allografts with acute rejection. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(3):E336–E344. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Zhang SL, Gao H. Expression of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in epithelial ovarian tumors and their clinical significance. China J Modern Medicine. 2009;19(8):1121–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rundhaug JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9(2):267–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowluru RA, Zhong Q, Santos JM. Matrix metalloproteinases in diabetic retinopathy: potential role of MMP-9. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21(6):797–805. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.681043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mi XS, Yuan TF, Ding Y, Zhong JX, So KF. Choosing preclinical study models of diabetic retinopathy: key problems for consideration. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2311–2319. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S72797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato T, Kusaka S, Shimojo H, Fujikado T. Vitreous levels of erythropoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor in eyes with retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(9):1599–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, Kostyk SK, D'Amato R, Sullivan R, D'Amore PA. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35(1):101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park K, Chen Y, Hu Y, Mayo AS, Mayo AS, Kompella UB, Longeras R, Ma JX. Nanoparticle-mediated expression of an angiogenic inhibitor ameliorates ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization and diabetes-induced retinal vascular leakage. Diabetes. 2009;58(8):1902–1913. doi: 10.2337/db08-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hapsari D, Sitorus RS. Intravitreal bevacizumab in retinopathy of prematurity: inject or not? Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2014;3(6):368–378. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong RK, Hubschman S, Tsui I. Reactivation of retinopathy of prematurity after ranibizumab treatment. Retina. 2015;35(4):675–680. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Rosa M, Messori A. The safety of bevacizumab and ranibizumab in clinical studies. Int Ophthalmol. 2015;35(2):157–158. doi: 10.1007/s10792-015-0043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Castellanos MA, Schwartz S, Hernandez-Rojas ML, Kon-Jara VA, Garcia-Aguirre G, Guerrero-Naranjo JL, Chan RV, Quiroz-Mercado H. Long-term effect of antiangiogenic therapy for retinopathy of prematurity up to 5 years of follow-up. Retina. 2013;33(2):329–338. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318275394a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammad G, Siddiquei MM. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in the development of diabetic retinopathy. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor. 2012;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12177-012-9091-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das A, McGuire PG, Erigat C, Ober RR, Dejuan E, Jr, Williams GA, McLamore A, Biswas J, Johnson DW. Human diabetic neovascular membranes contain high levels of urokinase and metalloproteinase enzymes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(3):809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beránek M, Kolar P, Tschoplova S, Kankova K, Vasku A. Genetic variations and plasma levels of gelatinase A (matrix metalloproteinase-2) and gelatinase B (matrix metalloproteinase-9) in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1114–1121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]