Abstract

The PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) pathway of the unfolded protein response (UPR) is protective against toxic accumulations of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, but is thought to drive cell death via the transcription factor, CHOP. However, in many cell types, CHOP is an obligate step in the PERK pathway, which frames the conundrum of a prosurvival pathway that kills cells. Our laboratory and others have previously demonstrated the prosurvival activity of the PERK pathway in oligodendrocytes. In the current study, we constitutively overexpress CHOP in myelinating cells during development and into adulthood under normal or UPR conditions. We show that this transcription factor does not drive apoptosis. Indeed, we observe no detriment in mice at multiple levels from single cells to mouse behavior and life span. In light of these data and other studies, we reinterpret PERK pathway function in the context of a stochastic vulnerability model, which governs the likelihood that cells undergo cell death upon cessation of UPR protection and while attempting to restore homeostasis.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Herein, we tackle the biggest controversy in the UPR literature: the function of the transcription factor CHOP as a protective or a prodeath factor. This manuscript is timely in light of the 2014 Lasker award for the UPR. Our in vivo data show that CHOP is not a prodeath protein, and we demonstrate that myelinating glial cells function normally in the presence of high CHOP expression from development to adulthood. Further, we propose a simplified view of UPR-mediated cell death after CHOP induction. We anticipate our work may turn the tide of the dogmatic view of CHOP and cause a reinvestigation of its function in different cell types. Accordingly, we believe our work will be a watershed for the UPR field.

Keywords: apoptosis, cell survival, Ddit3, GADD153, homeostasis, metabolic stress

Introduction

Widespread realization about the importance of the unfolded protein response (UPR) and metabolic stress in the pathogenesis of degenerative diseases has sparked a plethora of in vitro and in vivo studies to define molecular pathways and identify therapeutic targets that can be used to mitigate patient symptoms. The broad understanding of signaling cascades downstream of UPR activation have been relatively unchanged for over a decade (Harding et al., 2002; Kaufman, 2002; for review, see Gow and Sharma, 2003), although there are considerable uncertainties about some specific details.

For example, transient suppression of global protein synthesis in response to UPR signaling occurs through a transcriptional time-delay cycle initiated by dimerization and transautophosphorylation of the endoplasmic reticulum-resident PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). This triggers phospho-inactivation of the eukaryotic initiation factor, eIF2, induces expression of several transcription factors, and eventually leads to the expression of the GADD34 regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase I, which dephosphorylates phospho-eIF2α and reactivates global protein synthesis. However, the mechanism by which this regulatory cycle protects cells from the pathogenic consequences of unfolded protein accumulation and yet actively kills cells upon UPR activation, or more specifically upon expression of the transcription factor CHOP, remains unclear and controversial.

In a previous study, we characterized a Chop gene loss-of-function mouse mutant (via homologous recombination), which exhibits a severe degenerative phenotype when crossed to the rumpshaker (rsh) mouse. The rsh mouse is a naturally occurring CNS myelin mutant harboring a missense mutation in the X-chromosome Plp1 gene, which induces a UPR in oligodendrocytes but normally confers a mild disease phenotype. Subsequent studies by other groups have confirmed the disease-enhancing phenotype associated with UPR inactivation, using Perk gene loss-of-function phenotypes in oligodendrocytes that are exposed to UPR-inducing stimuli, such as proinflammatory cytokines (Lin et al., 2005, 2007).

The beneficial effects of CHOP expression on myelination are not limited to the CNS. Indeed, Schwann cells of the PNS-expressing missense mutant forms of the major myelin protein zero undergo UPR induction and express CHOP, which does not induce cell death but rather enables these cells to survive by dedifferentiation and subsequent redifferentiation (Pennuto et al., 2008; Saporta et al., 2012). CHOP expression in non-neural cells, including chondrocytes and adipocytes, also modulates dedifferentiation and/or differentiation, not cell death, under metabolic stress conditions (Batchvarova et al., 1995; Tsang et al., 2007). In light of such data indicating the prosurvival effects of CHOP expression in multiple cell types, we sought to directly test the contrary and pervasive view in the published literature that CHOP expression constitutes an obligate prodeath signal.

In the current study, we take a direct in vivo approach and examine the effects of chronic CHOP overexpression in myelinating cells of both the CNS and the PNS during development, in adulthood, and in the absence or presence of protein misfolding. We find in three independent lines of transgenic mice, as well as in transgenic myelin mutants undergoing postnatal UPR disease in oligodendrocytes, that continuous CHOP expression and localization to the nucleus have few, if any, detrimental consequences for myelinating cells and confer no detectable phenotype for the animals. These data suggest that, during a UPR, or under otherwise normal physiologic conditions, transgenic overexpression of CHOP neither causes nor exacerbates levels of apoptosis. Together with our previously published studies of other molecular components downstream of PERK activation (Sharma and Gow, 2007; Sharma et al., 2007), these data warrant a reinterpretation of the PERK pathway as the central mediator of cell death under metabolic stress conditions. Finally, we present a model of the UPR cycle, for which we integrate apparently disparate prosurvival and prodeath activities of the PERK pathway in terms of stochastic vulnerability for cells emerging from the UPR and reestablishing homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Expression cassette and transgene generation.

The 4.2 kb promoter-enhancer from the mouse 2′, 3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′- phosphohydrolase (Cnp) gene was a kind gift from Michele Gravel (Gravel et al., 1998). We modified this cassette in two ways to generate the transgene expression cassette, pCG. First, we inactivated the Kozak consensus sequence (Kozak, 1987) in exon 0 of the promoter-enhancer to eliminate an open reading frame (ORF) that could otherwise generate out-of-frame polypeptides from the chop coding sequence. This ensures that all transcripts generated from the transgene encode CHOP. To do this, we mutagenized the ATG to TTG in exon 0 using Quikchange (Agilent Technologies) primers: 5′-CGC CCA CTC ATC TTG GTG AGC GCA G-3′ (sense) and 5′-C TGC GCT CAC CAA GAT GAG TGG GCG-3′ (antisense). The underlined nucleotides show the A-to-T mutation in the translation start codon (bolded nucleotides). Second, we added 1.6 kb of genomic sequence from the human β-globin gene containing exons 2 and 3 to provide polyadenylation signals (Gow et al., 1992).

To generate the CchopG transgene for the current study, we TA-cloned and bidirectionally sequenced an RT-PCR product containing the mouse Chop ORF in pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) using primers: 5′-GGA TCC ATG GCA GCT GAG TCC CTG C-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGA TCT TTC ATG CTT GGT GCA GGC TG-3′ (antisense). The primers contain BamHI or BglII restriction enzyme sites for cloning into the unique BamHI site of pCG. The NotI fragment of pCchopG comprising the transgene is 6 kb.

In vitro generation of CHOP-null SCC23 cell clones.

Both alleles of the CHOP gene in the human oral squamous carcinoma cell line, SCC23, were functionally inactivated using CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering at the Genome Engineering and iPSC Center, Washington University. The guide RNAs to direct CHOP gene editing were 5′-GAG TCA TTG CCT TTC TCG CTT-3′ and 5′-GGA GGA GCC AGA ACC AGA GAG-3′. Three independent cell clones were established and two (1E1 and 3A4) were used in the current study. The SCC23-1E1 clone was characterized in greatest detail by sequencing the CHOP gene to identify the allele-specific genetic mutations. These mutations comprise deletions of differing lengths: a 1 bp deletion in exon 3 (chr12:57,517,381 del G on the GRCh38/hg38 human genome assembly) and a 3 bp deletion in exon 4 (chr12:57,517,108-10 del GAC) for CHOP allele a, and a 274 bp deletion from exon 3 to exon 4 (chr12:57,516,108-57,516,380 del) for allele b. Both mutant alleles encode nonsense proteins after 9 codons of the CHOP ORF but may permit expression of stable processed mRNAs.

In vitro characterization of the CchopG transgene.

Both SCC23-1E1 and SCC23-3A4 clones were stably transfected with each of three plasmids: (1) the pCMV-chop plasmid encoding mouse CHOP used to generate the transgene in this study; (2) the empty transgene parent plasmid, pCG; and (3) the pCchopG transgene plasmid used to generate transgenic mice in this study.

Each of the pCMVchop, pCG, and pCchopG plasmids was mixed 10:1 (molar ratio) with a pcDNA3.1zeo selectable marker plasmid (catalog #V86020, ThermoFisher Scientific) and transfected into 35 mm culture dishes of SCC23-1E1 and SCC23-3A4 cells using FuGENE HD (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer. After 3 d, all of the transfected plates were trypsinized and seeded onto 150 mm culture dishes for growth in culture medium containing 100 μg/ml zeomycin (Zeocin, catalog #R25001, ThermoFisher Scientific). After 9 d, cells from several zeomycin-resistant colonies were harvested from the plates and expanded (not cloned by limiting dilution) for characterization by immunofluorescence labeling with anti-CHOP antibodies. The SCC23-1E1 cells grew more rapidly than SCC23-3A4 cells (a growth property of these parent clones) and were characterized further.

UPR induction/survival assay in SCC23-1E1 cells.

Cells (7500 cells plated) were grown in 96 well plates for 48 h with tunicamycin in the culture medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin). CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) was added to the wells, and fluorescence measured from a plate reader was used to determine cell viability as recommended by the manufacturer and established procedures (Xi et al., 2015). Thereafter, the cells were harvested using Cells-to-CT (Ambion, Invitrogen), and gene expression was quantified by qPCR according to established procedures (Xi et al., 2015).

Mice and genotyping.

All experiments involving mice were performed in compliance with the Department of Laboratory and Animal Sciences guidelines at Wayne State University under the auspices of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols A 04-02-09 and A 03-01-12, as approved by the Animal Investigation Committee. Mice were maintained on a hybrid background strain of C57BL/6 × C3H. To maintain this background, we continuously backcrossed the mutant mice in our colony with purchased B6C3F1/Tac males (Taconic Farms).

CchopG transgenic mice [Tg(Cnp-Ddit3)786Gow, MGI:5318476] were generated by pronuclear injection into embryos from a C57BL/6J × SJL F1 hybrid strain by the transgenic core at from the University of Michigan. Founder mice were backcrossed for two generations to purchased B6C3F1/Tac females (Taconic Farms) and then to the X-chromosome linked mutant proteolipid protein 1 (Plp1) strains, either rumpshaker (rsh) or myelin-synthesis deficient (msd) mice on a B6C3F1/Tac background (Southwood et al., 2002). In these cases, both the CchopG and Plp1 mutant alleles were carried through the female germline, and these mice were backcrossed with B6C3F1/Tac males for 5–10 generations. The ORF of transgene-derived mouse CHOP expressed in transgenic mice was confirmed by bidirectional sequencing of tail DNA that was PCR amplified from transgenic mice.

Mice were genotyped between 6- and 10-d-old from tail/toe biopsy DNA using PCR. Biopsies were initially frozen on dry ice for storage at −80°C and subsequently digested with 0.4 mg/ml proteinase K (Promega) in Direct PCR buffer (Viagen Biotech) at 55°C overnight as recommended by the manufacturer. The transgene is detected in mouse genomic DNA as a 385 bp product generated using PCR primers: 5′-TGG AGC CAG AGA CTA AGA GGT TAG G-3′ (sense; Cnp promoter) and 5′-CTG CAG ATC CTC ATA CCA GGC TTC C-3′ (antisense; Chop ORF). Primers to genotype the msd mutant allele are as follows: 5′-TTG TGC TTG CTT TTC TGT TCT AAG AAA TAA-3′ (AG0214, sense) and 5′-TTA CCA GGG AAA CTA GTG TGG CCT CAG CAC-3′ (AG0215, antisense), which generate a 125 bp product (PCR conditions: 94°C, 60 s; 55°C, 90 s; 72°C, 120 s; 35 cycles) for Fnu4H I restriction (New England Biolabs) to digest the wild-type allele (88 + 37 bp). The rsh allele is identified using primers 5′-GCT GAT TTT TAA CCA CTC CAT GTC-3′ (AG0521, sense) and 5′-CAA CTC ACC ATA CAT TCT GGC ATC-3′ (AG0522, antisense), to generate a 212 bp product (PCR conditions: 94°C, 60 s; 55°C, 90 s; 72°C, 120 s; 35 cycles) that is restricted with Acc I (New England Biolabs) to identify the rsh allele (150 + 62 bp).

Southern and northern blotting.

For Southern blotting, genomic DNA was purified by overnight digestion of tail biopsy at 55°C with 0.7 ml of 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K (Promega), 0.5% SDS, 0.1 m EDTA in 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0. Samples were phenol:chloroform extracted, precipitated in 3 volumes of ethanol, and the pellets dissolved overnight at 55°C in 10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0. DNAs were double-digested with BamHI for 6 h in the presence of spermidine and electrophoresed overnight on 0.8% agarose gels at 30 V. Gels were acid/alkali treated, transferred to Nytran SPC membrane (Whatman), and probed as detailed previously (Gow et al., 1999).

For northern blotting, tissue samples were rapidly dissected, rinsed briefly in PBS, pH 7.4, and frozen in 13 ml Falcon tubes (Fisher Scientific) on dry ice. To purify total RNA, frozen testes were homogenized using an Ultra-turrax, model T50, fitted with a microprobe (IKA Works) for 1 min in 2 ml of 4 m guanidinium isothiocyanate containing 0.5% sodium lauroyl sarcosine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1 m mercaptoethanol added freshly. Homogenates were briefly centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatants were overlaid onto 3 ml columns of 5.7 m CsCl in SW55 tubes (Beckman Coulter) for centrifugation at 35,000 rpm for 20 h at 22°C. Northern blots were generated using 5 or 10 μg total RNA samples run on 1% formaldehyde-agarose gels (Chirgwin et al., 1979) and probed as detailed previously (Stecca et al., 2000).

Probes for Southern and northern blots were 32P-labeled using a Klenow-based random-priming kit as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs) and included the 0.4 kb ORF fragment of mouse Chop that was cloned into the pCG transgene. For Southern blots, 1–2 × 106 dpm/3 ml hybridization solution was used; for Northern blots, 3–4 × 106 dpm/3 ml hybridization solution was used.

Antibodies.

Antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-CHOP [1:4000, B1259 (Southwood et al., 2002)]; mouse anti-CHOP (1:500, clone B3, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-CHOP (1:1000, clone L63F7, catalog #2895S, Cell Signaling Technologies); mouse anti-GAPDH (1:10,000, clone 6C5, catalog #sc-32233, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-β-actin (1:1000, catalog #A1978, Sigma-Aldrich); rat anti-PLP (1:100, clone AA3); rat anti-BrdU (1:100, clone BU1/75; catalog #MAS-250p, Harlan Sera-Lab); mouse anti-CNP (1:5000, catalog #SMI91, Covance); anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:2000, catalog #RA15046, Neuromics); rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:300, catalog #019-1974, Wako); mouse anti-CD68 (1:300, catalog #MCA1957, AbD Serotec); and mouse anti-MBP (1:5000, catalog #SMI94, Covance). Species-specific and isotype-specific secondary antibodies were obtained from Southern Biotechnology, and all other secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen.

Western blotting.

Optic nerves and cervical spinal cords were rapidly dissected from decapitated mice and frozen on dry ice. Samples were subsequently homogenized with an Ultra-turrax homogenizer for 1 min in cell lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm PMSF, protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich; catalog #P8340; concentration as recommended), and benzonase (1:400 dilution; EMD Millipore) in 10 mm Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4. Protein concentrations were measured by Bradford (Bio-Rad), and 5–30 μg of protein per lane was electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. For SCC23 cells, whole-cell lysates were prepared using modified RIPA buffer (Fribley et al., 2004) and 100 μg of protein was loaded onto gels. Proteins were transferred to Protran membranes (ThermoFisher Scientific) and developed as previously described (Southwood et al., 2012).

Immunocytochemistry and in vivo BrdU labeling of mice.

Mice between 1.5 d (P1.5) and 6 months of age were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 400 mg/kg 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Sigma) in sterile saline and perfused through the left ventricle with freshly prepared 4% PFA (Sigma) in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, at room temperature for 15 min. Tissues were dissected and infiltrated with 40% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate, pH 7.2, overnight at 4°C and embedded in OCT (ThermoFisher Scientific) for cryostat sectioning as described previously (Wu et al., 2012). Ten micrometer sagittal or coronal sections of brain and spinal cord were mounted on Superfrost plus slides (ThermoFisher Scientific) and stored at −20°C. Sections were permeabilized in methanol at −20°C (except for anti-CD68 antibody labeling, where sections were permeabilized with 0.1% saponin), and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in block solution [1% BSA (catalog #A2153, Sigma), 0.1% gelatin (catalog #G-1890, Sigma), 2% normal goat serum, 0.1% saponin (Sigma) in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.5]. Sections were labeled with primary antibodies overnight at room temperature in block solution and washed between with Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.5. Sections were finally mounted using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), and coverslips were sealed with nail polish. For BrdU (Sigma) labeling, mice were injected intraperitoneally with a 5 mg/ml stock solution in sterile saline at a dose of 50 mg/kg and perfused as described above after 3 h. To expose DNA-incorporated BrdU in cryostat sections, slides were incubated in freshly diluted 4 m HCl for 15 min followed by 2 × 15 min washes in freshly prepared 0.1 m sodium borate, pH 8.5. Slides were then processed for immunocytochemistry.

qPCR assays.

Cervical spinal cords and optic nerves were rapidly dissected from killed mice and frozen on dry ice for storage. Individual samples were homogenized in QIAzol (QIAGEN) using an Ultra-turrax T8 homogenizer (ThermoFisher Scientific), and total RNA was purified using a RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini kit (QIAGEN) as recommended by the manufacturer. Sample quality was initially assessed for quality and found to be 1.92 ≥ A260/A280 ≥ 2.09. The samples were immediately reverse-transcribed (RT) to cDNA using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) as recommended by the manufacturer. An additional measure was used to verify cDNA quality by demonstrating the linear amplification of each sample by RT of TAT-binding protein mRNA from 400 ng and 2 μg aliquots of mRNA. qPCR analysis was performed in 384 well plates using a CFX384 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). Details of mouse-specific TaqMan probes (Invitrogen) used in this study were as follows: Atf3, Mm00476032_m1; Atf4, Mm00515324_m1; Atf6, Mm01295319_m1; Bak, Mm00432045_m1; Bax, Mm00432051_m1; Bim, Mm00437796_m1; Bip, Mm00517691_m1; Caspase3, Mm01195085_m1; Chop, endogenous (Chopi), Mm00492097_m1; Chop, total (endogenous + transgene), Mm01135937_g1; Der2, Mm00504288_m1; Gadd34, Mm00435119_m1*; Herpdu, Mm00445600_m1; Mbp, Mm01262037_m1; Mog, Mm00447824_m1; p21CIP, Mm04207341_m1; Plp1, Mm01297210_m1; Xbp1splice, Mm00457357_m1*; and Tbp, Mm00446973_m1. The human-specific TaqMan probes (Invitrogen) used were as follows: CHOP, Hs01090850_m1; XBP1splice, Hs03929085_g1; BIP, Hs99999174_m1; GADD34, Hs00169585_m1; and 18S, Hs99999901_s1.

Microglial morphometry.

Random epifluorescence images for analysis were captured at 20× magnification using an ORCA-R2 camera (Hamamatsu) attached to a Leica DM5500 B research microscope (Leica Microsystems) and quantified using MetaMorph version 7.7.2.0 (Molecular Devices). To analyze microglia, we focused solely on anti-IBA1-labeled cell bodies with a DAPI+ nucleus. Microglia were considered activated when an IBA1+ cell body was also labeled with anti-CD68 antibodies above background fluorescence.

Relative microglial cell body size and area of tissue occupancy were determined using a grid overlay (MetaMorph) with grid squares twice the size of the largest IBA+ cell body (60 × 60 screen pixels). The number of cell bodies intersected by the grid was counted. After moving the grid in the x- and y-planes by 30 pixels, cell bodies intersected were recounted and averaged with the initial count. The number of cells intersected was then normalized to microglia per field to compute relative cell area and proportion of activated (CD68+) cells.

Kaplan–Meier plots.

Wild-type and CchopG4 mice on either rsh or msd genetic backgrounds were weaned at P19-P21 and housed in mixed genotype cohorts up 120 d (rsh) or 60 d (msd). Ages of the mice at death were recorded and expressed as fractions. Mice living beyond these age windows were killed. The data were analyzed using Mantel–Cox and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon χ2 tests with 10 mice per genotype.

Rotarod analysis.

Motor coordination of mice was tested between 1 and 12 months of age (CchopG4 mice) or at 2 and 4 months of age (CchopG6A and CchopG6B mice) using a 2 d rotarod analysis (Med Associates) as described previously (Sharma et al., 2007). Briefly, mice were trained three times at 1 h intervals for 5 min on a rotarod accelerating linearly between 4 and 40 rpm on day 1. On day 2, the mice performed the same test, but the lengths of time on the rod were recorded and averaged for each mouse.

Electron microscopy and g-ratios.

Mice at 4 months of age were anesthetized with 400 mg/kg 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Sigma) in sterile saline intraperitoneally, and perfused through the left ventricle with freshly prepared 4% PFA/0.5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate (Electron Microscopy Sciences) buffer, pH 7.2, at room temperature for 60 min. The mice were then stored overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber before dissection at room temperature and sample collection. The dissected tissue was postfixed with osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and embedded in Araldite (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for electron microscopy using an EM1010 (JEOL) as previously described (Devaux and Gow, 2008).

Electron micrographs from wild-type and transgenic mice were analyzed using OpenLab software, version 5.0.1. Axon circumference and the myelin thickness were measured using a digitizing tablet (Wacom Technology) and the equivalent circular axon and fiber diameters computed. Electron micrographs from which g-ratios were measured were selected based on the quality of axon and myelin morphology. Thus, the histograms of axon diameters reported between wild-type and transgenic mice are approximate and not meant to signify an unbiased analysis of axon diameter.

Auditory brainstem responses (ABRs).

One-month-old mice were anesthetized with 375 mg/kg avertin injected intraperitoneally. ABRs were elicited using 8, 16, and 32 kHz tone pips at sound intensities of 80-20 dB sound pressure level (SPL) and were recorded bilaterally between mastoid and vertex subdermal electrodes as described previously (Gow et al., 2004). Left and right ear ABRs were measured and averaged for each mouse, with five mice analyzed per genotype. Interpeak latencies of the ABRs, which are strongly dependent on intact myelination (Gow et al., 2004), were calculated as a measure of cochlear and brainstem function in the auditory pathway.

Statistical analyses.

All statistical tests were performed using Prism software version 5 (GraphPad). Mean ± SEM values were calculated for statistics, with the number of mice used per genotype between 3 and 10 as indicated in the figure legends. These numbers of independent measurements were used to compute test statistics for significance.

Results

Early studies of UPR function proposed that expression of the transcription factor CHOP, which is several steps downstream of PERK activation, directly activates cell death in cultured cells and in vivo (Zinszner et al., 1998; Oyadomari et al., 2002). However, the impact of loss-of-function alleles of Chop on UPR-related disease is modest to variable (semidominant phenotypes). In light of contemporary studies, a proapoptotic function for CHOP seems less tenable, at least for several cell types (Southwood et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2005; Tsang et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2008; Saporta et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013).

Indeed, transcriptomics analysis of CHOP targets does not identify the proapoptotic cascade that would be expected for a proapoptotic regulator (Han et al., 2013). Other in vitro studies suggest that imbalance between different facets of UPR signaling to the nucleus leads to the generation of proapoptotic signals (Ron and Walter, 2007), although in vivo evidence demonstrates that this interpretation, too, is problematic (Lin et al., 2013). We have previously proposed that PERK signaling is an evolutionarily conserved pathway that protects cells from metabolic stress, but at the cost of increased vulnerability to a loss of homeostasis and stochastic cell death as the PERK time delay circuit completes each cycle and restores protein synthesis (Southwood et al., 2002; Gow and Wrabetz, 2009), and recent data lend support to this view (D'Antonio et al., 2013; Han et al., 2013).

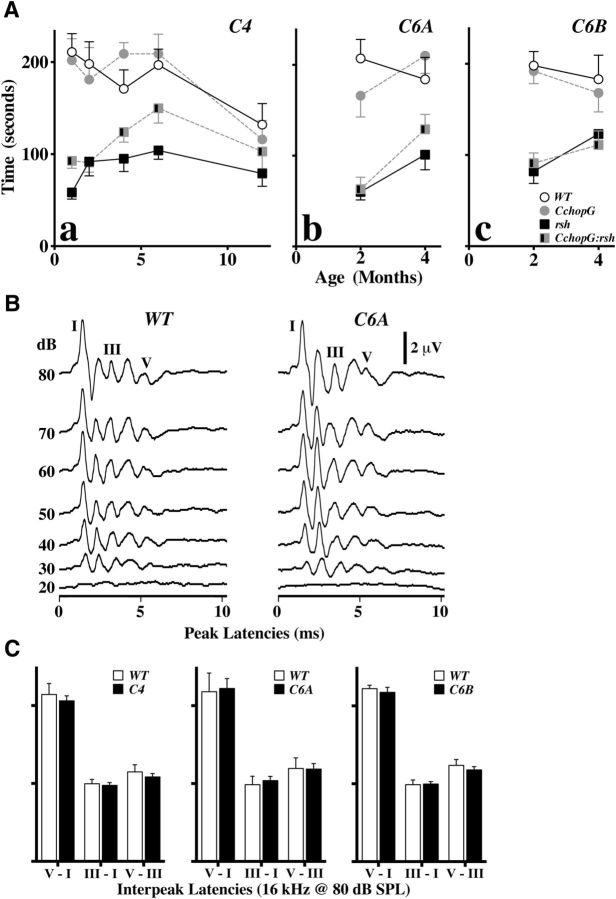

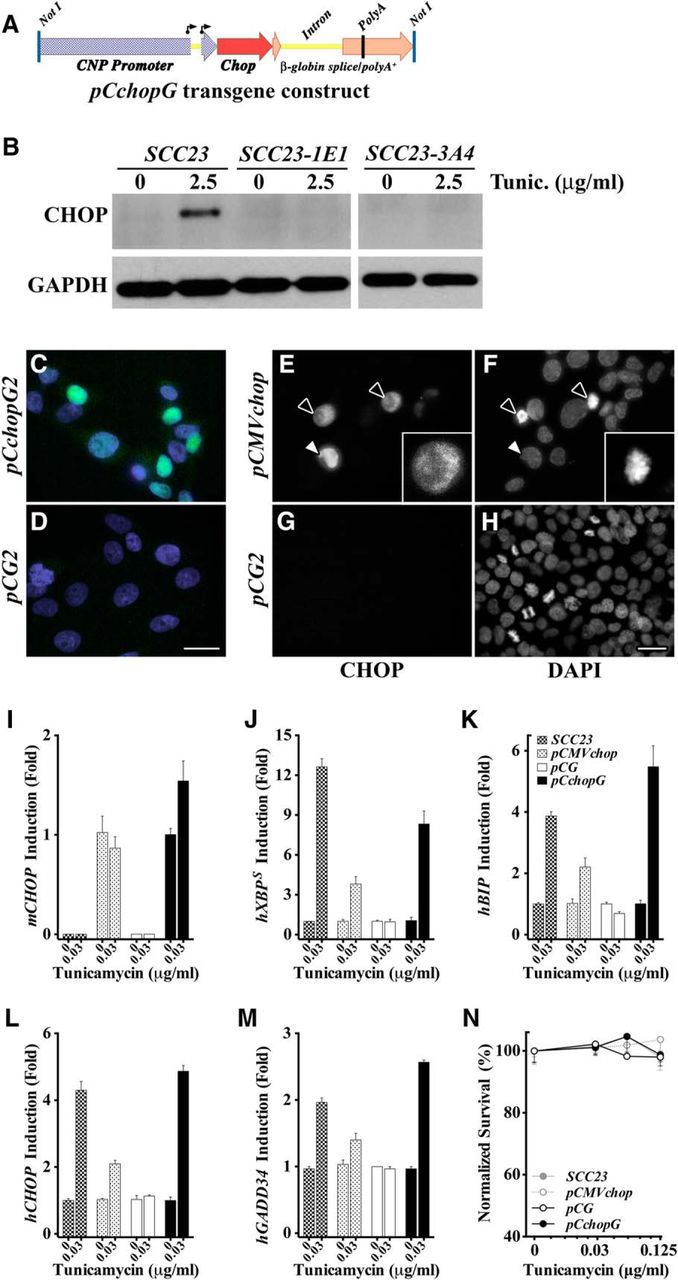

In vitro characterization of the CchopG transgene

The mouse Cnp gene promoter-enhancer was used to drive expression in the CchopG transgene for this study (Fig. 1A). We characterized the biological activity of the transgene-derived mouse CHOP protein in an in vitro paradigm, by generating stably transfected cell lines from SCC23 cells (Xi et al., 2015) in which both alleles of the endogenous human CHOP gene were functionally inactivated (SCC23-1E1 and SCC23-3A4 clones) by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. When challenged with 2.5 μg/ml tunicamycin in the culture medium for 6 h, parent SCC23 cells express CHOP protein, whereas the SCC23-1E1 (Fig. 1B) and SCC23-3A4 clones do not.

Figure 1.

In vitro characterization of the biological activity of transgene-derived CHOP. A, Schematic of the NotI-flanked, 6 kb CchopG transgene comprising 4.2 kb of the mouse Cnp promoter/enhancer and exon 0 through the 5 untranslated region of exon 1 (blue checker); the ORF of the full-length active mouse CHOP protein (red), and; a genomic fragment of the human-globin gene from the 3 portion of exon 2 to downstream of the polyadenylation signal in exon 3 (orange). The Cnp gene harbors two transcription start sites (arrows), but there are no AUG translation start sites upstream of the CHOP ORF. B, Western blots from SCC23 cell and the human CHOP-null clones, SCC23-1E1 and SCC23-3A4, lysates after growth with or without tunicamycin (2.5 μg/ml) in the culture medium for 6 h to induce a UPR. GAPDH is used as a control for cell lysate loading. C, D, Immunofluorescence staining of SCC23-1E1 cells stably transfected with pCchopG (C) or pCG plasmids (D). Mouse CHOP (green) is constitutively localized to the nucleus (DAPI, blue) in expressing cells. E–H, Immunofluorescence staining of SCC23-1E1 cells stably transfected with pCMVchop (E, F) or pCG plasmids (G, H). Black arrows indicate two CHOP-positive mitotic cells, in which the nuclear envelope has been disassembled and CHOP is localized to the cytoplasm. Inset, DAPI staining shows chromosome condensation in preparation for cell division. White arrows indicate a CHOP-positive interphase cell. I, qPCR of mouse Chop expression in SCC23 and SCC23-1E1 cells stably transfected with the pCMVchop or pCchopG plasmids. CHOP expression is constitutive, rather than being induced by tunicamycin, as expected for the CMV and Cnp promoter-enhancers. The Chop expression is not detected in the parent SCC23 cells or the pCG-transfected SCC23-1E1 cells. J, K, Cells grown in a low concentration of tunicamycin added to the culture medium for 48 h show activation of the IRE1 arm of the UPR by XBP1 splicing (J) and BIP gene induction (K). L, M, Cells grown in 0.03 μg/ml tunicamycin for 48 h show activation of the PERK arm of the UPR by induction of human CHOP and GADD34 mRNAs in SCC23 cells, and SCC23-1E1 cells (human CHOP mRNA encodes a nonsense protein in these cells) stably transfected with pCMVchop or pCchopG plasmids. These data demonstrate the expected biological activity of transgene-encoded mouse CHOP protein. The human PERK pathway genes are not induced in SCC23-1E1 cells transfected with pCG plasmid. N, Survival assay of cells grown for 48 h in the absence or presence of tunicamycin (0–0.125 μg/ml) shows that mild UPR induction is not cytotoxic to CHOP-positive or CHOP-negative cells.

Consistent with the apparent prosurvival activity of CHOP in myelinating cells in vivo (Southwood et al., 2002; Saporta et al., 2009), this transcription factor does not reflexively confer death on SCC23 cells undergoing a UPR. We have taken advantage of SCC23 cells lacking a functional endogenous CHOP gene to demonstrate the biological function of mouse CHOP expressed from the CchopG transgene in stably transfected SCC23-1E1 cells. In the absence of a UPR, the stable transfectants tolerate significant constitutive CHOP expression, despite nuclear localization and presumptive binding to cis elements in target genes (Fig. 1C). Moreover, CHOP-positive cells continue to divide under basal cell culture conditions (Fig. 1E,F). The CHOP protein is not detected in the negative controls (Fig. 1D,G,H).

Exposing stable transfectants and parent SCC23 controls to low-dose tunicamycin for 48 h (0.03 μg/ml) induces a UPR. Constitutive expression of mouse Chop mRNA is detectable in the pCchopG and pCMVchop transfectants but not the parent SCC23 cells or pCG-transfected cells (Fig. 1I). Tunicamycin induces the IRE1 pathway targets, human XBP1 splicing, and BIP expression, which demonstrates a UPR in all but the pCG transfectants. These data suggest a heretofore unrecognized regulation of IRE1 pathway activity by preemptive PERK activation, and indicating cells are marginally less sensitive to UPR stressors (rather than refractory) in the absence of CHOP (Fig. 1J,K).

Demonstration of the biological activity of transgene-derived mouse CHOP protein is shown in Figure 1L, M. The positive control SCC23 parent cells induce both human CHOP and human GADD34 mRNA expression under the UPR conditions of this assay. So too do SCC23-1E1 cells stably transfected with the mouse CHOP-encoding pCchopG and pCMVchop plasmids (human CHOP mRNA in these cells encodes nonsense protein, see Materials and Methods). Neither the CHOP nor GADD34 genes are induced in pCG-transfected SCC23-1E1 cells.

When exposed to higher concentrations of tunicamycin (0–0.125 μg/ml) for 48 h in a cell survival assay, CHOP-positive cells are no more sensitive to cell death, despite CHOP expression and UPR induction, than CHOP-negative cells (Fig. 1N). Together, these data demonstrate that the CchopG transgene expresses biologically active mouse CHOP protein, which constitutively localizes to the nucleus, induces expression of the (mutant) human CHOP gene and the known target GADD34, and does not induce cell death under these UPR conditions for at least 48 h. Finally, mouse CHOP does not induce CHOP or GADD34 gene expression in the absence of metabolic stress, despite constitutive nuclear localization in interphase cells.

The myelin Cnp gene promoter expresses specifically in oligodendrocytes

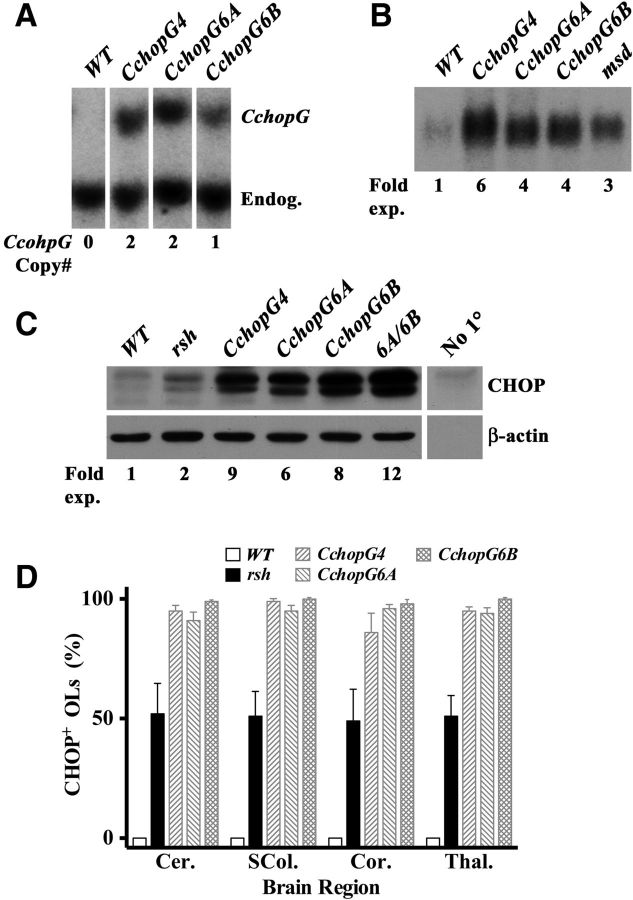

The Cnp promoter-enhancer drives transgene expression in oligodendrocyte lineage cells and Schwann cells. Three transgenic founder lines were generated from pronuclear injections of the pCchopG transgene, and Southern blot analysis reveals a single 6 kb band from BamHI-digestion of genomic DNA (Fig. 2A). An additional 3.6 kb hybridization band shows the endogenous Chop gene, which enables determination of the transgene copy number for each line.

Figure 2.

Oligodendrocyte-specific expression of the CchopG transgene. A, Southern blots used to determine copy number of the transgene in three independent lines of mice using the endogenous Chop gene (Endog.) as an internal control (two copies per genome). B, Northern blot of P16 spinal cord samples showing the relative expression levels of Chop mRNA in three independent lines of transgenic mice as well as wild-type (WT) littermates and age-matched msd mouse controls. C, Western blots from P16 optic nerve showing the relative expression levels of CHOP in three independent lines of transgenic mice and a compound heterozygote derived by breeding lines 6A and 6B compared with wild-type and rsh controls. Control lanes include β-actin to show loading and the No Primary (No 1°) lane to show antibody specificity. D, Morphometric analysis from four regions of P16 mouse brain to show the proportion of CNP+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells expressing CHOP from three independent transgenic lines as well as wild-type littermates and age-matched rsh controls. Cer, Cerebellum; SCol, superior colliculus; Cor, cortex; Thal, thalamus.

Northern blotting of total RNA from postnatal day 16 (P16) whole spinal cord in each of the transgenic lines demonstrates strong constitutive expression of Chop mRNA (Fig. 2B), which is fourfold to sixfold above littermate controls. In addition, this overexpression is approximately twofold greater than levels in the age-matched myelin-synthesis-deficient (msd) mouse, which is a naturally occurring Plp1 mutant strain harboring a missense mutation that induces a strong UPR in oligodendrocytes and confers a severe disease phenotype (Southwood et al., 2002).

Transgene-derived Chop mRNA is efficiently translated in the CNS as demonstrated by Western blotting from P16 optic nerve samples (Fig. 2C). CHOP runs as a doublet, which may reflect phosphorylation (Wang and Ron, 1996; Zinszner et al., 1998). Steady-state protein levels are sixfold to ninefold above littermate controls in the individual transgene lines and can be further increased to 12-fold over wild-type in compound heterozygous mice from lines 6A and 6B. These steady-state expression levels exceed CHOP expression in rsh mice by at least threefold (Southwood et al., 2002).

Although we observe a sixfold higher steady-state mRNA level in CchopG4 compared with wild type, steady-state protein in these mice is ninefold above wild-type (compare fold increases over wild-type for mRNA vs protein in Fig. 2B,C). This apparent increase in translation efficiency for CchopG-derived Chop mRNA likely stems from two additive effects: (1) deletion of negative RNA regulatory sequences in the transgene that have been identified in the endogenous Chop gene, such as the upstream ORF in the 5′ UTR (Jousse et al., 2001); and (2) high transgene-derived mRNA stability (we have previously shown that the human β-globin 3′ untranslated region using in our transgene confers significant transcript stability) (Gow et al., 1992).

A broad morphometric analysis of four brain regions using immunofluorescence microscopy to examine oligodendrocytes in P16 mice indicates that essentially all of these cells express the Chop transgene (Fig. 2D). Cryostat sections from three mice per transgenic line were surveyed and at least 100 CNP+ oligodendrocytes from each animal in each anatomical region were counted (mean ± SEM, n = 3). In all transgenic animals, >85% of oligodendrocytes express CHOP and localize this protein to the nucleus. Further, we obtained similar data from the brains of 6-month-old transgenic mice and from spinal cords of P2 mice (data not shown). In contrast, no oligodendrocytes from wild-type littermate controls and only 50% of these cells in age-matched rsh mice express the endogenous Chop gene. Thus, transgene expression follows the predicted expression pattern for the Cnp gene during development and in adulthood.

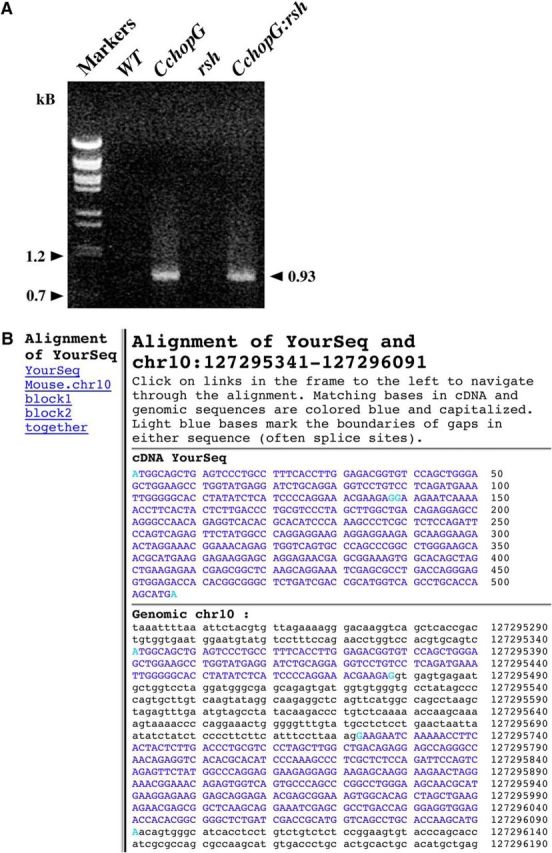

Finally, to ensure that the ORF of transgene-derived CHOP protein did not harbor missense mutations or indels that might give rise to loss- or gain-of-function phenotypes, we used PCR to amplify genomic DNA from the tails of transgenic mice and controls for direct sequencing. Agarose gel electrophoresis shows a single PCR product of expected size (0.93 kb) only from transgenic mice (Fig. 3A), which indicates that the amplification primers are specific for the transgene. Comparison of the PCR product sequences to the reference mouse genomic sequence (GRCm38/mm10) using the BLAT algorithm in the UCSC browser (Kent et al., 2002; Kent, 2002) reveals no mutations in the ORF of the transgene (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Confirmation of transgene-derived Chop cDNA sequence from transgenic mice. Transgene-specific primers were used to PCR amplify mouse Chop genomic DNA from tail biopsies of transgenic mice. A, A product of the expected size is only generated from transgenic mice. B, The PCR-derived DNA sequence was compared with the mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10 genome assembly) to confirm the correct ORF of the transgene.

Transgene-derived CHOP is localized to glial cell nuclei

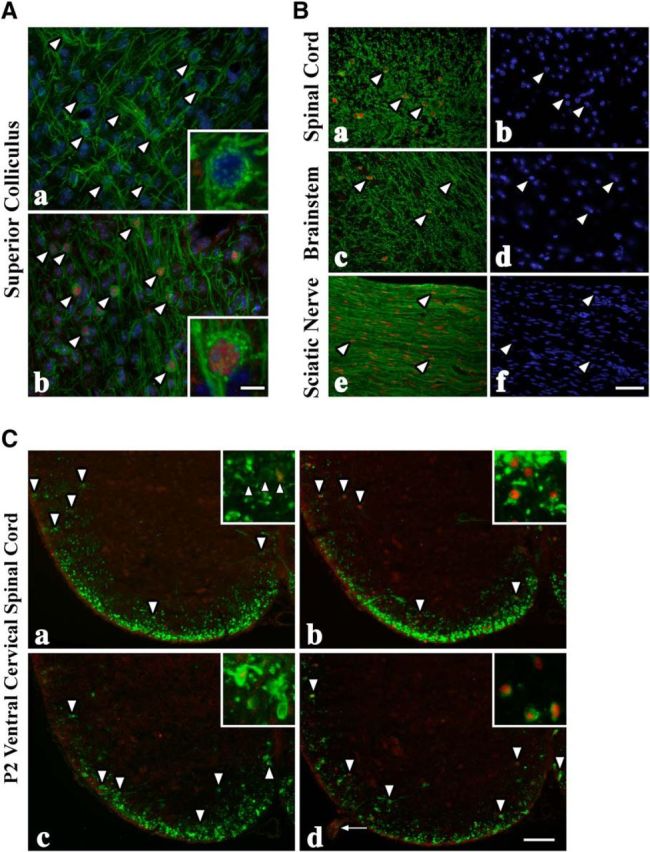

Using confocal microscopy, we examined vibratome sections from P16 transgenic mouse brain at high magnification to determine the subcellular localization of CHOP expressed in oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4A). In wild-type littermates, PLP1+ myelinated axons and oligodendrocyte cell bodies (Fig. 4Aa, arrowheads) are abundant in the superior colliculus (green labeling). The inset shows a single PLP1+ oligodendrocyte cell body at higher magnification with a DAPI-labeled nucleus. The green speckles over and around the nucleus of this cell likely reflect the locations of individual Golgi stacks in the cytoplasm, which have been shown using ultrastructural immunohistochemistry to accumulate PLP1 on route to myelin sheaths (Nussbaum and Roussel, 1983).

Figure 4.

CHOP expression in PLP1+ myelinating glia in CNS and PNS of CchopG mice. A, Through-focus confocal image stacks from the superior colliculus of P16 wild-type (Aa) and CchopG4 (Ab) mice showing PLP1+ (green) oligodendrocyte cell bodies (arrowheads) and myelin sheaths. Insets, High-magnification views of the cell bodies, which reveal individual PLP1+-Golgi stacks (green dots) and nuclear CHOP (red) in the transgenic mouse. B, PLP1+ oligodendrocytes and myelin in P16 spinal cord (Ba, b) and brainstem (Bc, d) from CchopG4 sections and CNP+ Schwann cells in sciatic nerve (Be, f). Essentially all myelinating glia (arrowheads) in the transgenic mice express CHOP and localize it to the nucleus. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). C, PLP1+ oligodendrocytes (arrowheads) are abundant in the ventral white matter tracts of P2 wild-type (Ca) and CchopG4 (Cb) mice. Nuclear CHOP is observed in occasional oligodendrocyte nuclei from wild-type and all oligodendrocytes from CchopG4 mice. Fewer PLP1+ oligodendrocytes are observed in rsh (Cc) and CchopG4:rsh (Cd) sections, but the CHOP labeling is similar to the cognate nontransgenic mice. In contrast, virtually all of the Schwann cells in the transgenic rsh mice express CHOP (arrow). Scale bars: Ab, 20 or 5 μm; Bf, 30 μm; Cd, 80 or 20 μm.

PLP1+ oligodendrocytes are found at normal density in the superior colliculus of transgenic mice, which are strongly labeled with anti-CHOP antibodies (Fig. 4Ab, red). The inset clearly shows that CHOP is present in the nucleus and not the cytoplasm, which indicates that this transcription factor is efficiently localized after synthesis and likely bound to DNA. In addition, PLP1+ Golgi stacks are abundant in the cytoplasm in similar fashion to the control, suggesting that this cell is healthy and is performing normally to myelinate surrounding axons. Indeed, the density of myelinated fibers in this micrograph is comparable with the controls, which confirms that oligodendrocyte function is relatively normal in the mutants. We obtain similar results in all three transgenic lines. Accordingly, we conclude that strong expression and nuclear localization of CHOP in oligodendrocytes from mid-gestation through adulthood are without detrimental effect on these cells in vivo.

In addition to gray matter regions of brain, we examined CHOP expression in white matter tracts (Fig. 4B). In all three transgenic lines, CHOP is expressed in CNP+ oligodendrocytes in P16 spinal cord (Fig. 4Ba,b), brainstem (Fig. 4Bc,d), and CNP+ Schwann cells of the PNS (Fig. 4Be,f). Further, we observe CHOP in spinal cords of P2 mice before there is substantial myelin membrane laid down (Fig. 4C). In each of these cases, CHOP is invariably and completely localized to glial cell nuclei. These data not only reveal appropriate processing and transport of CHOP in glia, but they also demonstrate that the nuclear morphology is that of healthy cells indistinguishable from surrounding CHOP− cells. In light of these data, it is difficult to reconcile the widely held belief in the UPR field that the mere expression of CHOP in cells drives apoptotic cell death. Rather, the death of cells undergoing a UPR appears to be contingent on additional factors.

Constitutive CHOP does not increase levels of oligodendrocyte death or shorten life span

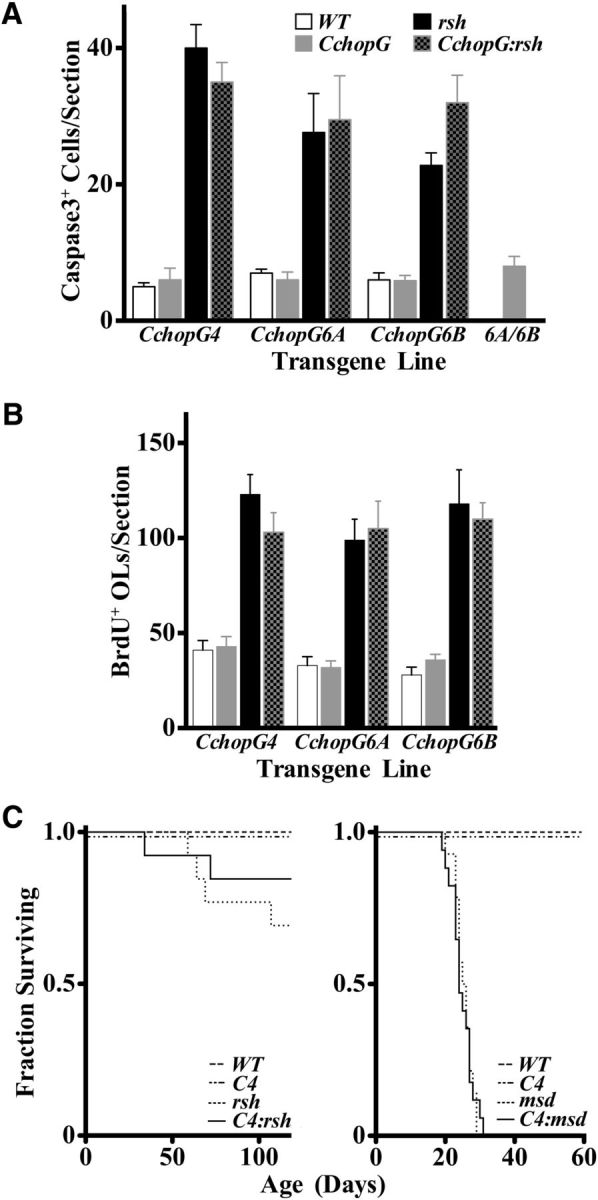

Although robust and constitutive expression of CHOP in oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells from transgenic mice does not cause widespread cell death, we cannot exclude the possibility that apoptosis of these cells might require activation of the UPR to be sensitized to apoptotic pathways as suggested by other studies (Chikka et al., 2013; Fribley et al., 2015). To test this possibility, we bred the three independent lines of CchopG mice to Plp1 mutant rsh and msd mice. Morphometric analysis of cervical spinal cord at P16 in these mice (Fig. 5A), which corresponds to a developmental period of significant apoptosis in rsh mice (Gow et al., 1998; Sharma and Gow, 2007), shows that the number of cells labeled with antibodies against activated caspase 3 is comparable in rsh and CchopG:rsh mice. The levels of apoptosis in wild-type and CchopG controls are also similar, although significantly lower than for the Plp1 mutants. To determine whether increasing the transgene expression level might induce cell death in wild-type oligodendrocytes, we generated compound heterozygous transgenic mice from lines CchopG6A and CchopG6B. Again, apoptosis was indistinguishable from controls and, accordingly, we can rule out the possibility that constitutive CHOP expression predisposes cells to death. Morphometry yielded similar results when TUNEL was used to identify apoptotic cells (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Oligodendrocyte apoptosis, progenitor cell proliferation, and the lifespan of CchopG mice are unaffected by transgene expression. A, The numbers of caspase 3+ cells in transverse sections of P16 wild-type cervical spinal cord (mean ± SEM, n = 3) are low and are unchanged in three independent transgenic lines as well as in age-matched compound heterozygotes derived by breeding CchopG6A and 6B mice (6A/6B). Caspase 3+ cells are elevated in rsh mice compared with the littermate controls, but there are no major changes over rsh caused by CHOP overexpression in the CchopG:rsh lines. Moreover, there are no statistically significant differences between rsh versus CchopG:rsh or WT versus CchopG for any of the transgenic lines (two-way ANOVA, p > 0.05). B, The size of the proliferative cell population is considerable in P16 in wild-type cervical spinal cord as revealed by BrdU+ cells. Most of these cells are from the oligodendrocyte lineage during myelinogenesis in the CNS. Similar to A, CHOP expression has little effect on the size of this proliferative population in any of the transgenic lines. There are no statistically significant differences between rsh versus CchopG:rsh or WT versus CchopG for any of the transgenic lines (two-way ANOVA, p > 0.05). C, Kaplan–Meier plots show that lifespan is not statistically altered by expression of the transgene in CchopG4 mice (χ2, p = 1); indeed, these mice live at least 1.5 years (data not shown). The lifespan of rsh mice (n ≥ 13) appears shortened to some extent (left) but is not statistically different in the presence of the transgene (χ2, p = 0.38). The severe phenotype of msd (right) is markedly more severe than rsh, and these Plp1 mutants have a shortened life span of 25–30 d (n ≥ 14). However, the presence of the CchopG4 transgene has negligible effect on longevity (χ2, p = 0.99). C4, CchopG4; OLs, oligodendrocytes.

In addition to measuring levels of apoptosis in cervical spinal cords of CchopG transgenic mice that harbor wild-type or rsh alleles of the Plp1 gene, we examined the levels of proliferating cells. In earlier studies, the proliferative oligodendrocyte precursor pool in Plp1 mutant jimpy mice (Vermeesch et al., 1990) and msd mice (A.G., unpublished data) was found to be twofold to threefold larger than that of wild-type mice. These data were interpreted to suggest that the length of the cell cycle was decreased for these cells in response to mutant Plp1 expression; however, a more likely explanation is that increased apoptosis levels of mature oligodendrocytes in the mutants are compensated by greater proliferation rates of the progenitors (Gow et al., 1998). Accordingly, we measured BrdU incorporation in spinal cords of transgenic mice from the current study to determine whether cell proliferation in CNS is normal (Fig. 5B). The data show that the number of BrdU-labeled cells in cervical spinal cord of P16 wild-type mice is indistinguishable from all of the CchopG lines, which indicates that there are unlikely to be abnormal levels of oligodendrocyte cell death associated with constitutive CHOP expression under homeostatic (WT vs CchopG) or UPR (rsh vs CchopG:rsh) conditions.

In addition to morphometric analyses, we also examined the survival of CchopG4:rsh and CchopG4:msd double-mutant mice. Cohorts of male mice were housed up to 120 d after birth in standard breeder cages to generate Kaplan–Meier plots and determine whether Chop transgene expression exacerbated the severity of disease caused by mutant Plp1 gene expression (Fig. 5C). In both the rsh and msd colonies, we found no instances of death for wild-type mice or CchopG4 single mutants. Similar numbers of rsh and CchopG4:rsh mice died at various ages during these experiments, and all msd and CchopG4:msd mice died between 20 and 30 d of age, which is typical for this severe form of disease. Together, these data demonstrate that constitutive CHOP expression in myelinating cells increases neither apoptosis nor progenitor proliferation at the single-cell level, and does not alter disease prognosis associated with Plp1 mutations at the level of the organism.

Normal immune cell responses in mutant mice expressing the CchopG transgene

In lieu of a major degenerative phenotype associated with constitutive expression of CHOP in myelinating cells, we focused in on more subtle cell-mediated responses in the CNS, such as the interaction of immune cells with oligodendrocytes expressing CHOP under normal development and UPR conditions. To do this, we examined activation of microglial cells, which are exquisitely sensitive to local cellular pathology and serve a variety of functions, including the removal of cell debris and chemokine-mediated recruitment of other immune cells to sites of damage or infection (for review, see Kettenmann et al., 2011).

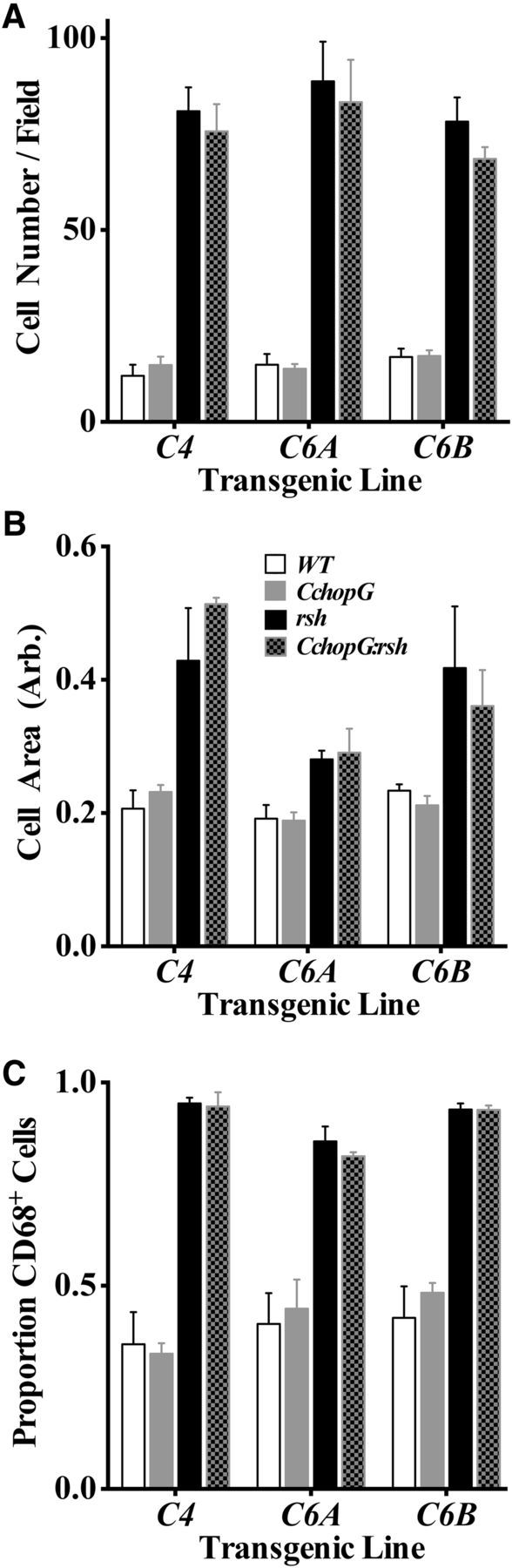

Microglia exhibit a stereotypic morphology in the resting state characterized by small cell body size, scant cytoplasm, and long fine spiny processes. This morphology abruptly changes upon activation to one of cell body enlargement, abundant cytoplasm, short thickened processes, and induction of activation markers, such as the lysosomal protein, CD68. Resting microglia occupy 3D nonoverlapping domains in the parenchyma at ∼10,600 ± 1785 cells per mm3 (10 cells per 20× field; Fig. 6A), and this density is unchanged in the three independent Chop transgenic lines. These data are somewhat higher than published estimates from 2 month spinal cord (5950 ± 1300) (Kondo and Duncan, 2009), which may reflect mouse strain differences.

Figure 6.

Normal immune surveillance in spinal cord myelinated tracts from CchopG transgenic mice. Morphometric analyses of microglial number and activation status in dorsal, lateral, and ventral funiculi at the level of the cervical spinal cord. The characteristics of microglia in all three lines of CchopG and CchopG:rsh mice were measured, in terms of cell density (A), area of the cell body (B), and the proportion of microglia expressing the lysosomal activation marker CD68 (C). All three parameters were found to be indistinguishable from littermate wild-type and rsh mice, respectively.

Microglial cell density increases approximately fivefold in rsh mice, by a combination of migration from surrounding gray matter regions, cell division, and extravasation. Expression of the Chop transgene does not alter the magnitude of this increase. In addition, rsh microglia exhibit an increase in the area of the cell body compared with controls, which is similar in the presence or absence of the transgene (Fig. 6B). Finally, cell body changes in rsh are accompanied by an increase in the proportion of microglia that express CD68, from ∼40% to >90%, which is indistinguishable from that of CchopG:rsh littermates (Fig. 6C). Together, these data indicate that constitutive expression of the CchopG transgene in otherwise wild-type oligodendrocytes does not confer detectable cellular pathology from the perspective of immune surveillance by microglia. Moreover, for microglia that detect cellular pathology in rsh mice and become activated, transgene expression in oligodendrocytes does not blunt or exacerbate this response.

Constitutive CHOP does not alter expression of UPR-, apoptosis-, or myelin-associated genes

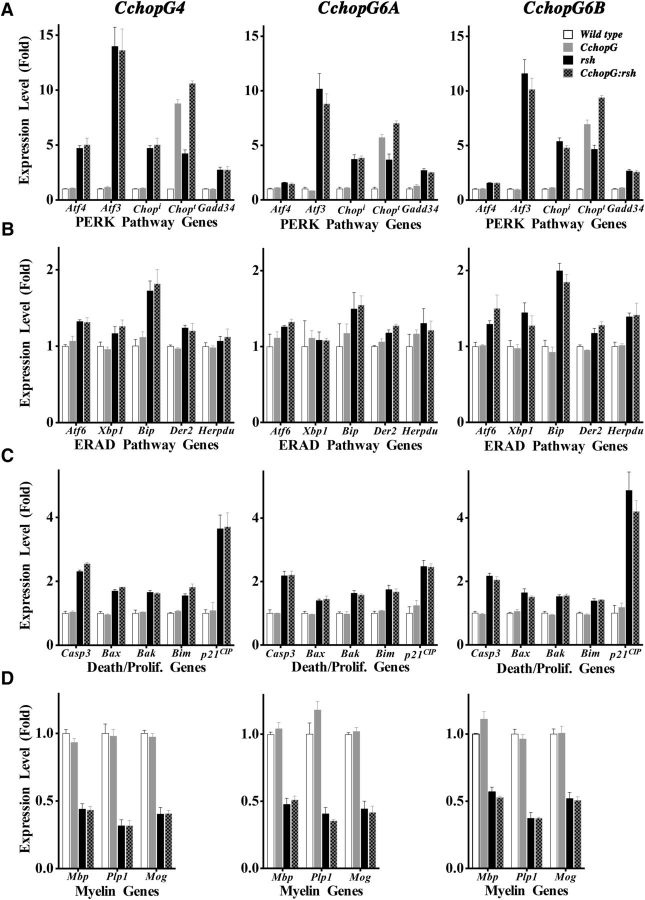

To identify subtle phenotypes at the molecular level, we examined the transgenic mice for changes in gene expression profiles in several pathways relevant to metabolic stress and the UPR: the PERK pathway, ERAD, apoptosis, and myelinogenesis. Quantitative TaqMan PCR analyses were performed in cervical spinal cord from P16 mice and normalized to the wild-type expression level for each gene. No differences are detected between the littermate controls and CchopG transgenic mice or between rsh and CchopG:rsh mice in any of the three lines for PERK pathway genes tested, except for the specific example of Chop mRNA expression in transgenic mice (Fig. 7A). These data are consistent with previous in vitro studies in MEFs overexpressing CHOP (Han et al., 2013) and our current data in SCC23-1E1 cells (Fig. 1), and demonstrate that expression of this transcription factor alone is not sufficient to induce UPR gene expression.

Figure 7.

qPCR analysis of steady-state RNA levels in spinal cord for UPR, cell death and differentiation, and myelin genes. Analyses of expression profiles in three independent transgenic lines for PERK pathway (A), ERAD (B), and cell death and proliferation (C) genes reveal that most are induced, and to similar extents, in rsh and CchopG:rsh mice compared with littermate controls. D, Analysis of expression profiles for three myelin genes show them to be decreased, and to similar extents, in rsh and CchopG:rsh mice compared with littermate controls. We find not statistical differences in expression levels for any gene compared between rsh and CchopG:rsh mice. Chopt in A, total Chop expression (i.e., the summation of endogenous, Chopi, and transgene-derived Chop). Thus, Chop transgene expression in CchopG:rsh mice is derived by subtracting Chopi from Chopt. For all genes, expression was determined from three technical replicates. Three biological replicates were measured per genotype for every gene (n = 3 mice). The TAT binding protein gene was used as the reference for normalizing all samples.

In this case, Chop expression in CchopG and CchopG:rsh mice exceeds that of wild-type and rsh mice, respectively, as expected (Fig. 2). Notably, Chop expression in the double-mutants falls short of the simple summation of endogenous Chopi (i.e., from rsh mice) and transgene expression (i.e., from CchopG mice). This occurs because the activity of promoter/enhancers for most myelin genes (CchopG expression is driven by the Cnp promoter/enhancer; Fig. 2A) is decreased by ∼50% compared with controls (Fig. 7D). Thus, Chop expression levels in CchopG:rsh mice approximate the summation of Chopi (from rsh) and half of the CchopG expression.

As anticipated from previous studies (Gow et al., 1998; Southwood and Gow, 2001; Southwood et al., 2002), expression of most Ire/ERAD- and apoptosis-related genes (Fig. 7A–C) is induced in rsh mice compared with controls, which reflects the pathophysiology of unbridled protein misfolding in these mice (Gow et al., 1994; Gow and Lazzarini, 1996). We do not observe significant differences in the expression profiles of these genes between rsh mice and CchopG:rsh mice, which suggests that the UPR operates maximally upon induction and is neither abetted nor hindered by the presence of (preexisting) supernormal levels of CHOP. Importantly, we find no evidence that constitutive CHOP expression sensitizes oligodendrocytes to proapoptotic pathways, as has been proposed in widely acknowledged models, which define CHOP as a proapoptotic protein (Rutkowski et al., 2006; Ron and Walter, 2007).

With respect to CNS myelinogenesis, we do not detect changes in the expression profiles of myelin structural genes in wild-type versus CchopG mice during development at a time when the rate of myelinogenesis is near its P21-P28 peak in brain (Fig. 7D). As expected, expression of myelin genes in rsh mice is decreased approximately twofold (Mitchell et al., 1992), and this phenotype is not altered by constitutive CHOP expression. Together, these data demonstrate that CHOP is a relatively neutral transcription factor under homeostatic conditions and that excess CHOP does not modify the overall activity of the UPR under metabolic stress conditions.

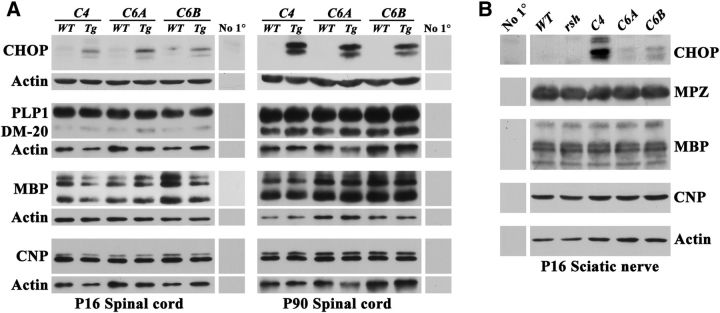

Normal expression of myelin structural proteins in the CNS and PNS of CchopG transgenic mice

To confirm the TaqMan data for myelin gene expression in Figure 7 and extend this analysis into the PNS, we performed Western blotting for several structural proteins in spinal cord and sciatic nerve at P16, as well as in spinal cord at P90. Figure 8A shows that steady-state levels of transgene-derived CHOP are similar between the three independent lines during development and increase in adulthood as the density of oligodendrocytes in the tissue increases. In the PNS, CchopG4 expression far exceeds that of the other lines. In addition, we observe a higher molecular weight species interacting with anti-CHOP antibody that is unique to the PNS (Fig. 8B). The origin of this band is unclear but may reflect post-translational modification associated with the high expression level. Despite supernormal levels of CHOP, we do not observe major changes in the levels of several myelin proteins, including PLP1, DM20, MBP, CNP, and myelin protein zero, indicating that major effects of transgene expression are absent in these mice.

Figure 8.

Steady-state levels of CNS and PNS myelin proteins in CchopG mice. Western blot analysis in three independent transgenic lines for myelin genes expressed at P90 and/or P16 in spinal cord (A) and sciatic nerve (B). In CNS, there are few differences in protein expression levels between the Chop transgenic mice and wild-type littermates, other than increased levels of CHOP expression. In sciatic nerve, CHOP expression is undetectable in wild-type and rsh controls and is markedly higher in the C4 line than the other two transgenic lines.

Normal myelin ultrastructure in CchopG optic nerves

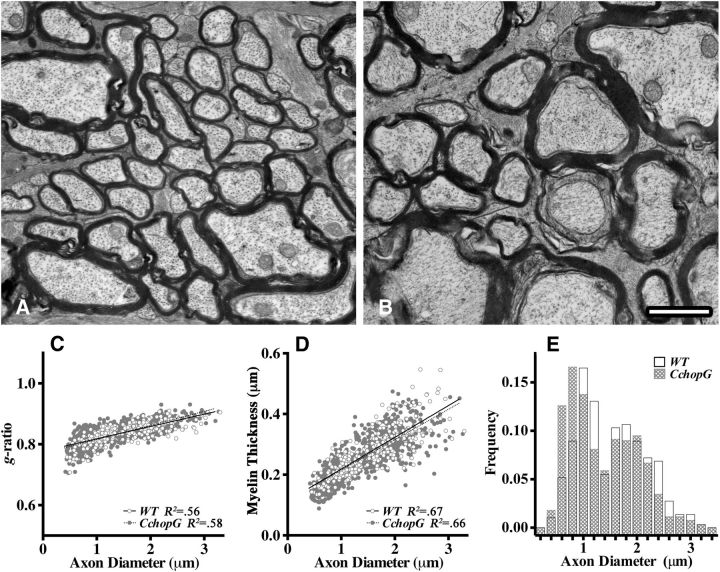

In view of the normalcy in levels of cell death, cell proliferation, and gene expression between wild-type and CchopG transgenic littermates, we examined myelin ultrastructure in optic nerves to determine whether subtle morphological changes might be associated with CHOP overexpression. Transverse sections of optic nerve midway between the retina and the chiasm from 4 month CchopG6B mice demonstrate that virtually all axons are myelinated. In micrograph surveys, we find no evidence of degenerating fibers or other markers of pathology, such as the presence of prominent intermediate filament-laden astrocyte processes. Further, the ultrastructure, orientation, and density of mitochondria, microtubules, and neurofilaments appears normal (Fig. 9A,B). Quantitative aspects of optic nerve ultrastructure for all three transgene lines, including plots for g-ratio, myelin thickness, and axon diameters (Fig. 9C–E), are indistinguishable from controls, indicating that we observe minimal changes in the presence of nuclear CHOP in oligodendrocytes. Accordingly, we conclude that myelin ultrastructure in transgenic mice is not perturbed.

Figure 9.

Normal myelin ultrastructure in optic nerves of CchopG mice. Transverse sections of optic nerve from CchopG6B mice (A) and littermate controls (B) are indistinguishable at the ultrastructural level with respect to the proportion of myelinated axons, the orientation and density of microtubules, as well as the size and abundance of mitochondria. C, D, Regression lines for the myelin g-ratios (C) and myelin thickness (D) around the axons from wild-type (solid) and CchopG6B (dashed) optic nerves are virtually identical over a wide range of axon diameters. Two mice per genotype were examined, and measurements were made from scanned micrographs examined at 6000–8000×. E, Histograms of the axon diameters used to determine g-ratios in C show the distributions for wild-type and CchopG6B sections. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Minimal impact of CchopG expression on motor coordination or sensory input in rsh mice

In the absence of changes in disease severity, apoptosis, immune surveillance, or gene expression profiles associated with constitutive CHOP expression in oligodendrocytes from CchopG or CchopG:rsh mice, we examined all three transgenic lines for systems changes that affect motor coordination and sensory input. We have previously demonstrated the utility of these approaches for identifying behavioral changes in mouse mutants that are not readily detected by other types of analysis (Gow et al., 1999; Stecca et al., 2000; Southwood et al., 2004).

In Figure 10A, CchopG4:rsh double-mutant male mice and littermate controls were assessed using a standard rotarod analysis between 1 and 12 months of age. Wild-type and CchopG4 transgenic mice perform well in this paradigm, and their levels of performance are indistinguishable using a two-way ANOVA for genotype and age with Tukey post hoc testing (p > 0.98). The rsh and CchopG4:rsh mutants perform rather poorly in this test compared with controls, particularly at young ages (p ≤ 0.04), but are indistinguishable from each other at all ages (p > 0.88). By 12 months, performance of the control groups has declined sufficiently so that no statistical differences are apparent between any of the genotypes (p > 0.13).

Figure 10.

Functional motor and sensory pathway analyses show no detrimental effects of CHOP overexpression in oligodendrocytes. A, Longitudinal rotarod analyses of three independent transgenic lines: CchopG4 (a), CchopG6A (b), and CchopG6B (c). Aa, Two-way ANOVA of the CchopG4 transgenic line between 1 and 12 months of age shows overall statistically significant differences for genotype (p < 0.0001) and age (p = 0.0003) with no overall interaction between these parameters (p = 0.055). Tukey post hoc tests corrected for multiple comparisons reveal that the performance of the control groups [wild-type (WT) and CchopG4 (C4)] are indistinguishable at every age (p > 0.98). Similarly, the rsh and CchopG4:rsh (C4:rsh) groups are indistinguishable from each other at all ages (p > 0.88). Tukey post hoc tests for WT versus rsh or C4 versus C4:rsh reveal statistical differences between 1 and 6 months of age (p ≤ 0.02 or p ≤ 0.04, respectively). In contrast, there are no differences between any of the genotypes at 12 months (p > 0.13). Number of male mice per genotype in all rotarod cohorts was ≥ 8, except for C4 2 month data in Aa (n = 5–8). Data are mean ± SEM. B, ABRs to 16 kHz pure tone pips from wild-type and CchopG6A mice are comparable both in terms of the threshold of hearing at ∼20 dB SPL and the amplitudes of Waves I-V. C, Interpeak latencies for the overall auditory pathway from the cochlea to the inferior colliculus (Waves V-I), the peripheral component of the pathway (Waves III-I), and the central component (Waves V-III) are comparable between three independent lines of CchopG transgenic mice and littermate controls.

To determine whether sensory systems might be perturbed by constitutive CHOP expression in myelinating cells, we measured ABRs to pure tone pips at several frequencies in adult CchopG mice. An example of ABR recordings is shown for CchopG6A mice and littermate controls in Figure 10B. A sound intensity series from 80 to 20 dB SPL shows the characteristic 5 wave (Waves I-V), stimulus-locked electroencephalogram response, with amplitude decreasing and latency increasing as functions of stimulus intensity. The threshold of hearing is apparent at 20 dB SPL for both genotypes by the flat response.

Interpeak latencies for the major ABR Waves (i.e., I, III, and V) are summarized in Figure 10C as a functional measure of the auditory pathway in these mice. The V-I interpeak latency is commonly used as a proxy for comparative overall conduction velocity along myelinated fibers in the auditory pathway from the cochlea to the auditory cortex. Conduction velocity through the peripheral portion of the pathway, which includes Schwann cell myelinated spiral ganglion neurons and oligodendrocyte myelinated eighth cranial nerve axons from the cochlea to the cochlea nucleus is estimated from Waves III-I. The central portion of the pathway comprises oligodendrocyte myelination from the cochlear nucleus to the cortex and is estimated from Waves V-III. We find no differences for these measures between CchopG mice and controls in all three lines, indicating that the function of myelinating cells in the transgenic mice is largely normal. Estimating conduction velocities from mice that harbor the rsh mutation is not possible using the current approach because the latter Waves IV and V are often ill defined or absent; thus, the total and central components of the pathway cannot be interrogated.

Discussion

One of the most enduring conundrums in the UPR literature revolves around an almost universal acceptance that activation of this signaling pathway is cell protective (the adaptive response) and yet is also directly responsible for initiating apoptosis through expression of the transcription factor CHOP, the maladaptive response. The conundrum arises because CHOP expression is an obligatory step in the PERK pathway. CHOP is necessary to induce the expression of target genes that enable cells in a UPR to return to homeostasis and resume normal metabolic function (specifically global protein synthesis). Thus, the question arises: how can an obligatory step simultaneously fulfill prosurvival and proapoptotic functions?

Widely accepted models of PERK pathway activation propose that CHOP is unstable when expressed at low levels during mild metabolic stress (Rutkowski et al., 2006; Ron and Walter, 2007). However, we have not detected such instability under conditions of mild versus severe levels of metabolic stress in oligodendrocytes from rsh and msd mice. Disease in rsh mice is associated with far less apoptosis than in msd mice, and yet we discern no differences in the time course of UPR induction during development or the extent to which UPR genes are induced (Gow et al., 1998; Southwood and Gow, 2001; Southwood et al., 2002; Sharma and Gow, 2007; Sharma et al., 2007). Indeed, our previous transcriptomics analysis reveals only subtle differences between mild and severe UPR disease, most probably linked to the number of cells undergoing metabolic stress rather than differences in the stress response itself (Southwood et al., 2013).

Other studies in oligodendrocytes are consistent with our findings (Lin et al., 2013). Further, the presence or absence of CHOP in Schwann cells undergoing a UPR does not determine cell survival (Pennuto et al., 2008; Gow and Wrabetz, 2009; Saporta et al., 2012). Perhaps a simple resolution to the conundrum is that the currently accepted UPR models involving proapoptotic CHOP require modification to more closely encompass all observations. In this regard, we have directly tackled the issue by constitutively overexpressing CHOP in myelinating cells of transgenic mice to determine whether this transcription factor induces apoptosis under normal physiological conditions or whether it predisposes cells, undergoing a UPR, to death.

In plain terms, we are unable to detect significant changes in mouse behavior, performance, cell survival, and function using a range of tests and systems approaches to examine mice overexpressing CHOP in myelinating cells. These remarkable findings indicate that constitutive expression and localization of CHOP to the nucleus in essentially all oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells are without significant or persistent consequence during normal development or in adulthood. Moreover, we do not detect changes, either positive or negative, in CchopG:rsh oligodendrocytes undergoing a UPR caused by the expression of mutant Plp1 gene products. We interpret these data to signify that CHOP plays little or no role in either promoting proapoptotic signals in vivo or sensitizing myelinating cells to apoptosis through a unilateral expression level-dependent mechanism. In contrast, such a mechanism has been demonstrated for cancer cells (Fribley et al., 2015).

Our data are consistent with a model in which the transcriptional activity of CHOP is low (but non-negligible; Fig. 1C,D) (Southwood et al., 2002) under homeostatic conditions and maximal from endogenous gene expression (i.e., saturated) under UPR conditions. Thus, constitutive CHOP expression has no discernible effects in normal cells, and there are few additive (i.e., constitutive + inducible CHOP) effects during a UPR. MEFs grown in culture and subjected to UPR conditions during constitutive CHOP expression behave similarly (Han et al., 2013). Nonetheless, we might expect that CchopG:rsh oligodendrocytes in the early stages of UPR induction (i.e., at the level of ATF4 target gene expression) would proceed more rapidly through the PERK pathway because of the constitutive availability of CHOP for driving expression of target genes, such as Gadd34. This would likely lead to premature dephosphorylation of phospho-eIF2α and the reinitiation of protein synthesis before the ERAD-mediated clearance of misfolded proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. Oligodendrocytes would more easily and more rapidly enter a new UPR cycle as they began to synthesize mutant PLP1.

If so, oligodendrocytes from CchopG:rsh mice should spend a greater proportion of time undergoing a UPR compared with rsh mice, which would increase steady-state expression of PERK pathway genes, such as Atf3 and Gadd34. However, we do not observe this effect from our expression data in Figure 7A, which suggests that constitutive CHOP does not hasten UPR progression. Thus, although CHOP is an obligatory step for completing a cycle of PERK activation, this transcription factor is presumably dependent on induction of additional genes and, therefore, is unlikely to be a rate-limiting or significant regulatory step in the PERK pathway. Such characteristics may limit the importance of CHOP as a target for disease modifying therapies, at least in glial cells.

Rethinking the role of PERK pathway activation in cell fate

As extensive as our data may be in this study, we cannot preclude the possibility that myelinating cells exhibit cell-specific metabolic activities that protect them from the proapoptotic role for CHOP observed in other cell types. Additional studies may resolve this possibility by defining whether a proapoptotic or protective activity is the archetypal function of CHOP. In the interim, our data afford an opportunity to posit a simplified model of the survival-death fate of cells undergoing a UPR.

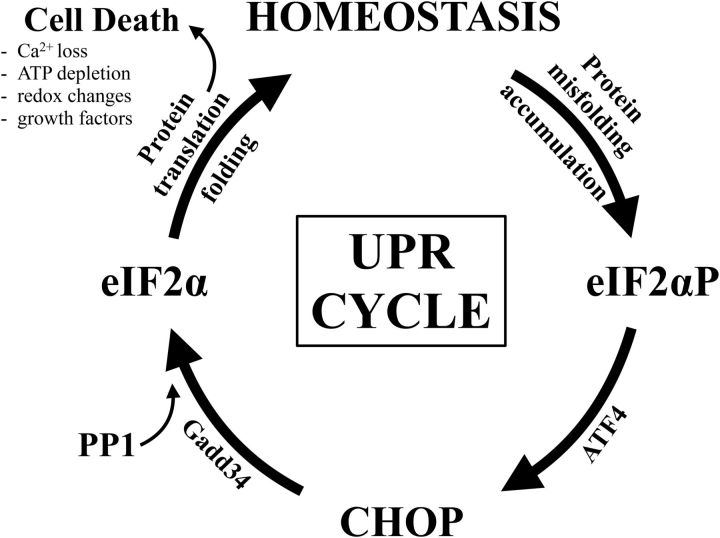

This model is not reliant on assumptions that CHOP expression is a rate-limiting step in the PERK pathway or that stability of the protein determines cell fate. Rather, this burden is shifted downstream to the dephosphorylation of phospho-eIF2α by the GADD34/protein phosphatase I complex, which provides cells with an opportunity to restore homeostasis. We posit that a failure to achieve homeostasis leads to cell death via any of its defined forms (Kroemer et al., 2009), probably in a context-dependent and cell type-specific manner.

A key concept for our simplified model is that of a UPR cycle, which can repeat indefinitely over time (Fig. 11). Thus, at the level of the cell, an accumulating mutant protein(s) induces a UPR and is degraded to allow exit from the UPR, but may subsequently accumulate again to induce another UPR cycle. Figure 2D demonstrates that ∼50% of myelinating oligodendrocytes from P16 rsh mice express CHOP and are in the midst of a UPR cycle. We interpret these data as a measure of steady state; thus, half of the oligodendrocyte population is undergoing a UPR and is transiting the PERK pathway, whereas the remaining cells are synthesizing myelin components, including mutant PLP1, and will subsequently enter or reenter a UPR cycle. This interpretation implies that oligodendrocytes spend ∼50% of their time in UPR cycles, which is largely determined by their metabolic activity. Thus, an escalation in the proportion of cells undergoing a UPR might reflect increased metabolism, with higher rates of protein synthesis causing individual cells to spend more time in UPR cycles. Conversely, reducing metabolic rate should reduce the proportion of the cell population in the UPR.

Figure 11.

Schematic of the UPR cycle. The UPR encompasses at least three pathways that are activated by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins. The PERK pathway is one of these and is activated by phosphorylation of the eIF2α protein to suppress global protein synthesis while activating expression of a series of transcription factors, including ATF4 and CHOP. CHOP expression is an important marker of PERK pathway activation, but our data suggest that it is unlikely to be a rate-limiting step. Nonetheless, CHOP expression is an obligatory step, which induces GADD34 expression, leading to dephosphorylation of phospho-eIF2α and the resumption of global protein synthesis. At this point of rekindled ribosome assembly, stochastic processes, such as the loss of calcium from endoplasmic reticulum stores, ATP depletion, redox changes/oxidative stress, or increased metabolism mediated by extrinsic growth factor signaling through cell surface receptors, may render cells transiently vulnerable to cell death as they attempt to restore normal cell function, leading to context-dependent and cell type-specific demise. In the event that cells reestablish homeostasis, subsequent metabolic events, such as the expression of a mutant protein in the case of rsh mice, cause protein aggregation and drive another UPR cycle and another period of stochastic vulnerability as the cell emerges from the UPR. Such periodic entry and exit from successive UPR cycles may continue for days or weeks or until the cell succumbs to apoptosis. Further, the more rapid or severe the accumulation of mutant proteins, the more frequently the cell activates the UPR and the greater the cumulative risk for apoptosis.

To account for UPR outcomes that are commonly attributed to CHOP proapoptotic activity, we propose that cells undergoing metabolic stress, such as oligodendrocytes in rsh mice, are in the midst of an indefinite succession of UPR cycles, and that the primary determinant of cell survival/death in each cycle is governed by stochastic vulnerability as global protein synthesis resumes. Calcium release from endoplasmic reticulum stores, ATP depletion, and generation of reactive oxygen species are examples of transient stochastic processes that could limit the capacity for cell revitalization and cause autonomous cell death via any of several known mechanisms (e.g., apoptosis, necroptosis). Alternatively, the presence of growth factors in the local milieu, such as during development, might increase metabolic demands via receptor-mediated signaling cascades, which would render vulnerable those cells emerging from a UPR cycle and lead to nonautonomous cell death. Such a circumstance might be considered paradoxical because growth factors are typically considered to improve cell viability.

In conclusion, from the view of our current and previous studies as well as those of other groups, our premise is that CHOP is a prosurvival protein representing the final regulatory step in a transcription-based protective time-delay circuit. CHOP is an important biomarker of the PERK pathway but is unlikely to be either rate-limiting or a major driver of pathway progression. Rather, CHOP enables the completion of each PERK activation cycle enabling cells to reengage global protein synthesis and restore normal function. Consistent with this conclusion, there is little direct evidence that CHOP induces prodeath signals in myelinating cells or several other cell types during the UPR (Batchvarova et al., 1995; Southwood et al., 2002; Tsang et al., 2007; Saporta et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2013).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Multiple Sclerosis Society Grant RG4078 and National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke Grants NS43783 and NS067157 to A.G., and National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant DE019678 and the Children's Hospital Foundation of Michigan to A.M.F. We thank Chad Beasley and Mike Bradley for technical assistance in the A.G. laboratory; and Dr. Mike Callaghan (Department of Pediatrics, Wayne State University) for helpful suggestions about the manuscript. The SCC23-derived CHOP-null cell clones were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing by Dr. Shondra Miller (Genome Engineering and iPSC Center at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Batchvarova N, Wang XZ, Ron D. Inhibition of adipogenesis by the stress-induced protein CHOP (Gadd153) EMBO J. 1995;14:4654–4661. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikka MR, McCabe DD, Tyra HM, Rutkowski DT. C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) contributes to suppression of metabolic genes during endoplasmic reticulum stress in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:4405–4415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.432344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirgwin JM, Przybyla AE, MacDonald RJ, Rutter WJ. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Antonio M, Musner N, Scapin C, Ungaro D, Del Carro U, Ron D, Feltri ML, Wrabetz L. Resetting translational homeostasis restores myelination in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1B mice. J Exp Med. 2013;210:821–838. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux J, Gow A. Tight junctions potentiate the insulative properties of small CNS myelinated axons. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:909–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fribley A, Zeng Q, Wang CY. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 induces apoptosis through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress-reactive oxygen species in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9695–9704. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9695-9704.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fribley AM, Miller JR, Brownell AL, Garshott DM, Zeng Q, Reist TE, Narula N, Cai P, Xi Y, Callaghan MU, Kodali V, Kaufman RJ. Celastrol induces unfolded protein response-dependent cell death in head and neck cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2015;330:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Southwood CM, Lazzarini RA. Disrupted proteolipid protein trafficking results in oligodendrocyte apoptosis in an animal model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:925–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Southwood CM, Li JS, Pariali M, Riordan GP, Brodie SE, Danias J, Bronstein JM, Kachar B, Lazzarini RA. CNS myelin and Sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent In Osp/Claudin 11-null mice. Cell. 1999;99:649–659. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Wrabetz L. CHOP and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in myelinating glia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Lazzarini RA. A cellular mechanism governing the severity of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Nat Genet. 1996;13:422–428. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Sharma R. The unfolded protein response in protein aggregating diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2003;4:73–94. doi: 10.1385/NMM:4:1-2:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Friedrich VL, Jr, Lazzarini RA. Myelin basic protein gene contains separate enhancers for oligodendrocytes and Schwann cell expression. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:605–616. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Friedrich VL, Jr, Lazzarini RA. Many naturally occurring mutations of myelin proteolipid protein impair its intracellular transport. J Neurosci Res. 1994;37:574–583. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490370504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]