Abstract

Background

The international community recognises violence against women (VAW) and violence against children (VAC) as global human rights and public health problems. Historically, research, programmes, and policies on these forms of violence followed parallel but distinct trajectories. Some have called for efforts to bridge these gaps, based in part on evidence that individuals and families often experience multiple forms of violence that may be difficult to address in isolation, and that violence in childhood elevates the risk of violence against women.

Methods

This article presents a narrative review of evidence on intersections between VAC and VAW – including sexual violence by non-partners, with an emphasis on low- and middle-income countries.

Results

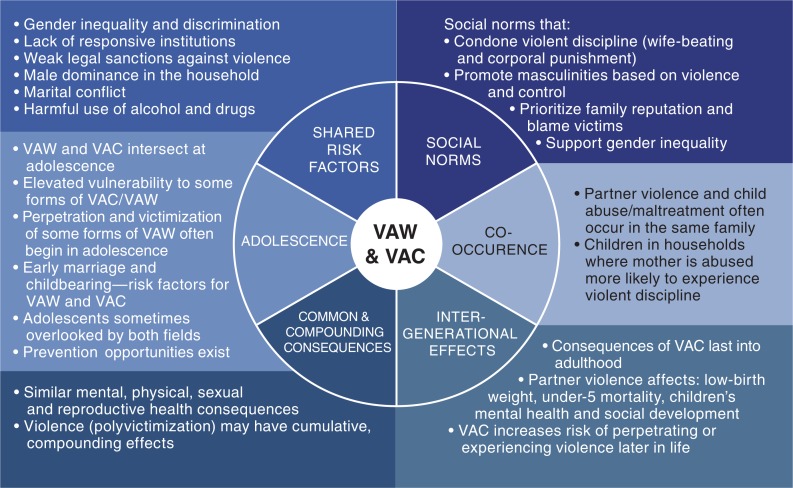

We identify and review evidence for six intersections: 1) VAC and VAW have many shared risk factors. 2) Social norms often support VAW and VAC and discourage help-seeking. 3) Child maltreatment and partner violence often co-occur within the same household. 4) Both VAC and VAW can produce intergenerational effects. 5) Many forms of VAC and VAW have common and compounding consequences across the lifespan. 6) VAC and VAW intersect during adolescence, a time of heightened vulnerability to certain kinds of violence.

Conclusions

Evidence of common correlates suggests that consolidating efforts to address shared risk factors may help prevent both forms of violence. Common consequences and intergenerational effects suggest a need for more integrated early intervention. Adolescence falls between and within traditional domains of both fields and deserves greater attention. Opportunities for greater collaboration include preparing service providers to address multiple forms of violence, better coordination between services for women and for children, school-based strategies, parenting programmes, and programming for adolescent health and development. There is also a need for more coordination among researchers working on VAC and VAW as countries prepare to measure progress towards 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, sexual violence, child maltreatment, child abuse, adolescents

Introduction

The international community has recognised violence against women (VAW) and violence against children (VAC) as global public health and human rights problems (1–3). According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, nearly one-third (30%) of ever-partnered women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a partner, and about 7% of women age 15 and older have experienced sexual violence by a non-partner, with wide variations by region (4). The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) estimates that 6 in 10 (almost 1 billion) children worldwide aged 2–14, experience regular physical punishment, and even higher proportions (about 7 in 10) experience psychological aggression; ‘harsh physical punishment’ – being hit hard repeatedly or on the face – affects an average of 17% of children from 58 countries where data are available, while about 1 in 10 girls under age 18 (approximately 120 million) worldwide have experienced forced intercourse or other unwanted sexual acts (2). Boys also report sexual abuse, usually at lower levels than girls (5). Studies from many countries also document high levels of emotional abuse and neglect of children (2).

Research, programmes, and policies on VAW and VAC have historically followed parallel but distinct trajectories, with different funding streams, lead agencies, strategies, terminologies, rights treaties, and bodies of research (6, 7). Some researchers have called for more efforts to bridge this divide based in part on evidence that research and services focused on one form of violence in isolation from others may overlook important risks, vulnerabilities, and consequences of multiple forms of violence within families and across the lifespan (6, 8–12). There have also been calls for closer collaboration between the two fields to help countries achieve and measure progress towards ending both forms of violence (13), as they committed to do as part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and targets (14).

Previous articles have reviewed intersections between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence, drawing largely on evidence from high-income settings (8, 9, 12, 15). This article provides a narrative review of the global evidence on intersections of VAC and VAW – defined more broadly to include sexual violence by non-partners. Based on a thematic analysis of international reviews and multi-country studies, we present a framework that includes six intersections: shared risk factors, social norms that condone violence and prevent help-seeking, co-occurrence of intimate partner violence and child maltreatment in the same household, intergenerational effects, common and compounded consequences, and a shared interest in adolescence. We review global evidence for each intersection with an emphasis on research from low and middle-income countries. We then discuss key gaps, policy implications, and opportunities for collaboration as well as possible risks.

Methods

Given the size of the global literature on VAW and VAC, a systematic review was neither feasible nor suited to our purpose. Systematic reviews that identify all relevant sources and select only those that meet strict methodological inclusion criteria are ideal for answering a specific research question; in contrast, narrative reviews can map themes that emerge from broad reviews of large or emerging bodies of research, using more flexible search methods and inclusion criteria (16, 17). This approach allowed us to identify broad intersections and summarise sub-themes across a wide range of sources from two large bodies of work. In keeping with guidelines for narrative reviews (16, 17), we did not perform formal quality assessments of each source, but whenever possible, relied on existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and multi-country, population-based studies.

We carried out searches in stages (described below) using PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, as well as hand searches of bibliographies and databases of international organisations. We limited sources to English language publications within the past 12 years (January 2004–December 2015), except for a few important older sources. We included peer-reviewed articles as well as reports and other publications by United Nations agencies and other international organisations.

Operational definitions and search terms

For purposes of this review, we focused on physical and sexual intimate partner VAW, and child maltreatment, but also sexual violence by non-partners against women, adolescents, and children. International human rights treaties endorse broad definitions of VAW and VAC that encompass a wide range of perpetrators, contexts, and forms, including acts of physical, sexual, and psychological violence, and (with regard to children) neglect and exploitation (1, 2). In practice, however, operational definitions that researchers use to measure different forms of violence vary widely (2, 4), are evolving, and are sometimes contested – as discussed in more detail within the body of this article.

Search terms included violence against children, child maltreatment, child abuse, child neglect, co-occurrence of domestic violence and child maltreatment, child exposure to intimate partner violence/domestic violence, violent discipline, corporal punishment, child sexual abuse, sexual exploitation of children, adolescents, youth, polyvictimisation VAW, gender-based violence, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, spouse abuse, rape, forced sex, sexual coer coercion, and sexual violence. Additional terms were used for moretargeted searches for each of the six intersections (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Search terms and strategies for individual intersections

| Intersection | Search terms | Search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Shared risk factors | Risk factors, correlates, perpetration, victimisation, review, systematic review, and meta-analysis combined with all search terms used for developing the framework. | Sources selected for this section were limited to international reviews (prioritising systematic reviews), meta-analyses and population-based multi-country studies with data from low and middle-income countries. |

| Social norms | Social norms, gender norms, attitude, social values, help-seeking, review, systematic review, and meta-analysis combined with search terms used to develop the framework. | In addition to published articles and reviews, we extracted data on attitudes about violence from Demographic and Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Surveys taken from UNICEF sources (2, 59). |

| Co-occurrence | Co-occurrence, review, systematic review, and meta-analysis combined with all search terms related to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence. | In additional to review articles and multi-country studies, we searched for individual studies from low and middle-income countries, excluding studies that considered exposure to domestic violence (alone) as a form of child maltreatment. |

| Intergenerational effects | Intergenerational effects, transmission of violence, consequences, long term effects, polyvictimisation, review, systematic review, and meta-analysis combined with search terms used to develop the framework (particularly terms related to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence). | In addition to review articles and multi-country studies, we searched for individual studies from low and middle-income countries. |

| Common and compounding consequences | Consequences, long-term effects, polyvictimisation, mental health, sexual and reproductive health, review, systematic review, and meta-analysis combined with all search terms used to develop the framework. | In addition to review articles and multi-country studies, we searched for individual studies from low and middle-income countries. |

| Adolescence | Adolescence, victimisation, perpetration combined with search terms used to develop the framework. | For the review of conceptual frameworks and operational definitions, we used sources from UN agencies and international research programmes, including Demographic and Health Surveys, World Health Organization surveys and Violence Against Children Surveys. For the discussion of adolescence as a time of vulnerability we drew from the previous review of risk factors and from the programmatic literature about promising responses to violence prevention. |

Mapping key intersections

To identify intersections, we analysed the themes that appear in international publications identified using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

English language;

global or multi-national sources focused on low and middle-income countries;

literature reviews (systematic when possible), meta-analyses or large, population-based multi-country studies;

addressed VAW, VAC, or both;

had a broad focus that included prevalence, risk factors, consequences, and policy implications (excluding sources with narrow research questions or focused on specific dimensions of violence such as consequences or interventions);

reviews of intersections between the two forms of violence (again excluding those that focused on a narrow research question or a single intersection);

published in peer-reviewed journals or by international organisations such as United Nations agencies;

published within the past 12 years (except for the 2002 WHO World Report on Violence which remains an important source for its global scope).

This search identified 48 sources, including:

25 global (or low and middle-income country) reviews or meta-analyses (1–5, 18–37)

10 population-based, multi-national studies or research programmes on VAW or VAC or both (38–47)

13 reviews of intersections between VAW and VAC (6–12, 15, 48–52).

A preliminary list of intersections was presented during the keynote speech at the 2013 Sexual Violence Research Initiative Forum (53) and revised after discussions with researchers at the 2015 Know Violence Expert Meeting in London.

Global evidence for each intersection

Next we carried out more targeted searches to produce brief reviews of the global evidence for each intersection. Again, a systematic review of each intersection was not feasible given the size of the literature and our aim, which was to provide brief overviews rather than in-depth or definitive summaries of the evidence. Google Scholar yields over 1.7 million sources for risk factors for VAW and VAC each, so our review of risk factors drew on the evidence from the 48 publications mentioned earlier, complemented by a targeted search for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and population-based multi-country studies with evidence on risk factors from low and middle-income settings. When reviewing evidence on co-occurrence, intergenerational effects, and common consequences, we also searched for individual studies from low and middle-income countries to provide examples of emerging bodies of work on those themes.

Sources from high-income countries comprise a majority of the published literature. For example, a PubMed search of (‘child abuse’ or ‘child maltreatment’) AND (‘domestic violence’ or ‘intimate partner violence’) from January 2011 through December 2015 identified 474 sources (excluding case reports), of which about one-fifth (84) came from low and middle-income countries, and nearly half (225) came from the United States of America (USA). This pattern is common across the indexed literature.

Results

Our thematic assessment of the global literature identified six key intersections between VAW and VAC, each with a series of sub-themes (Fig. 1). These categories are not designed to be strictly mutually exclusive. For example, social norms and intergenerational effects constitute risk factors, but are included as intersections in their own right because they are the focus of such a large portion of the literature and because they have programme and policy implications that go beyond elevated risk.

Fig. 1.

Intersections between violence against women (VAW) and violence against children (VAC).

Shared risk factors

International reviews and multi-country studies identify many similar risk factors for perpetrating VAW and VAC (Table 2). Both tend to be more common in societies with weak legal sanctions against violence, social norms that condone violence, high levels of social, economic, legal and political gender inequality, and inadequate protections for human rights; and within communities with weak institutional responses to violence and high levels of criminal violence or armed conflict (18–20, 23). Studies from high, middle, and low-income countries find elevated rates of child maltreatment and partner violence in families characterised by marital conflict, family disintegration, economic stress, male unemployment, norms of male dominance in the household, and the presence of non-biological father figures of children in the home (8, 27, 54).

Table 2.

Shared risk factors for perpetration of violence against women and violence against children

| Individual (perpetration) |

• Witnessed or experienced violence as a child • Young age • Alcohol and drug use • Depression • Personality disorder/antisocial behaviour • Attitudes that condone violence and gender inequality |

| Family/household | • Marital conflict/family breakdown • Male dominance in the family • Economic stress • Poverty/destitution • Non-biological father figures |

| Community | • Institutions that tolerate/fail to respond to violence • Community tolerance of violence • Lack of services for women, children, families • Gender and social inequality in the community • Community norms about privacy in the family • High level of criminal violence or and armed conflict |

| Societal | • Weak legal sanctions • Social norms that support violence, including physical punishment of wives/children • Social, economic, legal, and political disempowerment of women |

Studies worldwide find many common, if not universal, individual risk factors for male perpetration of intimate partner violence (54, 55), non-partner rape (56), sexual violence (28), and child maltreatment (20). These include childhood exposure to violence, young age (as in adolescence and early adulthood), personality disorders, antisocial behaviour, harmful use of alcohol or drugs, depression, criminal activity, and attitudes that support gender inequality or condone violence. Similarly, many studies have found elevated risks of experiencing physical or sexual violence among women exposed to violence in childhood – either as victims or witnesses (57, 58).

Social norms that condone violence and pose barriers to help-seeking

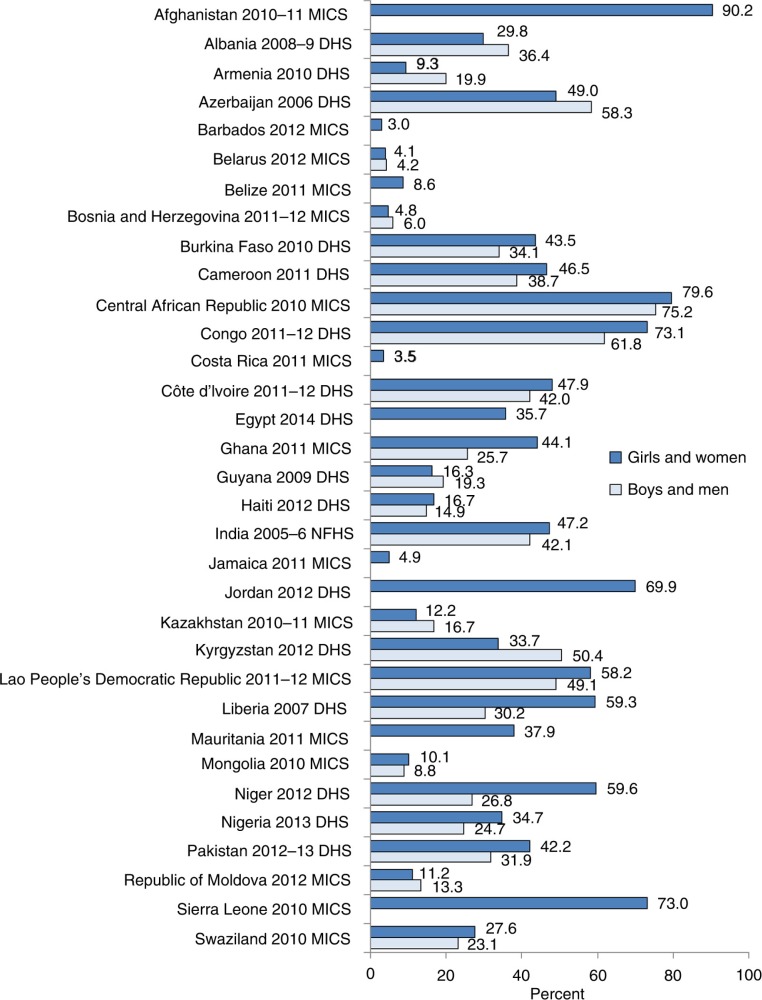

Worldwide, social norms that condone violence and support gender inequality merit attention, both as risk factors and as barriers for help-seeking. VAW is often justified, blamed on victims, or considered less important than reputations of perpetrators, families or institutions. For example, in many national surveys around the world, substantial proportions of women and men agree that wife-beating is justified for at least one reason, though figures vary widely by country (Fig. 2) (59). A World Bank analysis of national surveys from 55 countries (representing about 40% of the world population) found that 4 of 10 women agreed wife-beating was justified under some circumstances (60). A multi-level analysis of survey data from 44 countries found that norms condoning wife-beating and male control of female behaviour were among the strongest predictors of physical and sexual partner VAW at national and subnational levels, stronger than gross domestic product (61).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of women and men who agreed wife-beating is acceptable for at least one reason, selected national surveys 2010–2013 (59).

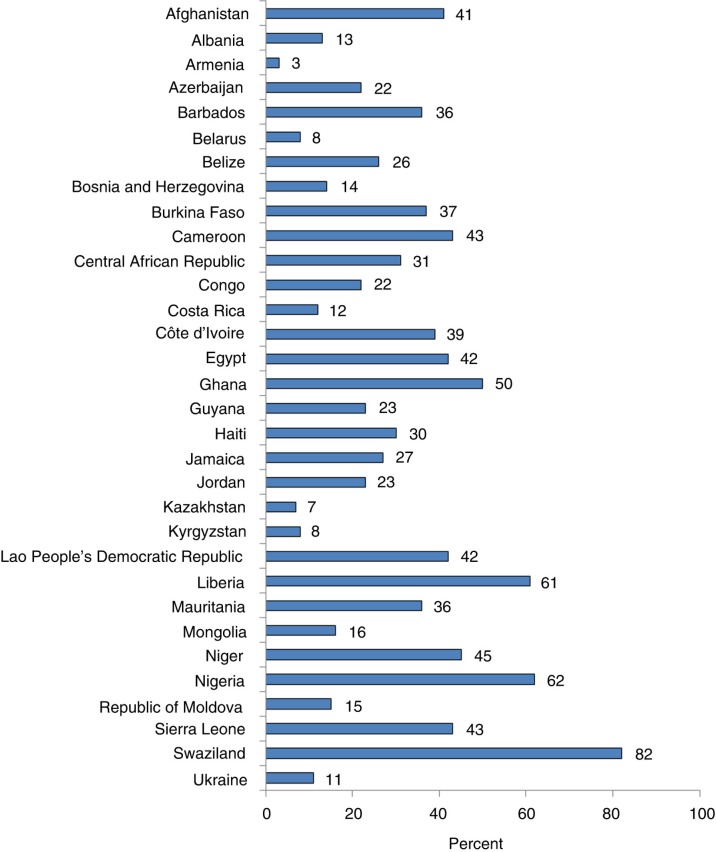

Similarly, despite international rights treaties recognising corporal punishment of children as a form of violence, it remains legal in schools or homes in 150 of 198 countries as of December 2015 (62). In national surveys from many countries, between 3 and 82% of adult caregivers say physical punishment is necessary for raising children (Fig. 3) (59). It is likely that even higher proportions believe it is acceptable in some circumstances.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of caregivers who agreed corporal punishment is necessary for raising children, selected national surveys 2005–2013 (2).

Research suggests links between acceptance of wife-beating and corporal punishment. In surveys from 25 low and middle-income countries, mothers who believed wife-beating was justified were significantly more likely than other women to believe that corporal punishment is necessary for raising children, and children of mothers who supported both wife-beating and corporal punishment were more likely than other children to experience psychological or physical violence (63).

In many settings, social norms blame victims rather than perpetrators and reinforce male sexual entitlement and men's right to control women. These attitudes have been linked to high levels of sexual violence against women and adolescents in diverse settings, including Asia and the Pacific (56), North America (64), and South Africa (65, 66). In some settings, large proportions of survey respondents consider it acceptable to kill a wife, sister or daughter who ‘dishonours’ the family (67), or to sexually harass women who dress provocatively (68).

Norms that prioritise family privacy over victim well being pose barriers to help-seeking for women who experience violence. In five national surveys from Latin America and the Caribbean, between one-fourth and one-half of women said that people outside the family should not intervene when a husband abuses his wife (39). These norms – along with fears of abandonment or retribution and lack of confidence in local services – contribute to low levels of help-seeking by women who experience violence (40, 41).

Norms that prioritise family reputation and blame victims also pose barriers to help-seeking for children, while norms about masculinity contribute to low disclosure rates by boys who experience sexual abuse (2). An analysis of seven national surveys found that few child survivors of sexual abuse disclosed their experience, even fewer received services, and perpetrators rarely suffered consequences (42, 43). For example, in Kenya, less than half of children who experienced sexual violence told anyone; less than one-fourth sought services; and less than 4% of girls and 1% of boys actually received services (69).

Co-occurrence of child maltreatment and intimate partner violence

Co-occurrence refers to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence that co-occurs in the same household during the same time period. A large body of research from high-income countries indicates that children in families affected by partner violence are more likely than other children to experience child abuse and neglect (29, 70). A USA study found that in as many as 4 of 10 households affected by partner violence, children also experienced physical abuse (71).

A smaller but growing literature from low and middle-income countries also documents co-occurrence, including studies from Hong Kong (72), India (73), Iraq (74), the Philippines (75), Romania (76), Taiwan (77), Thailand (78), Vietnam (79), and Uganda (80). Similarly, DHS surveys in many countries find that children in households affected by intimate partner violence are significantly more likely than other children to experience violent discipline (39, 81–83). Surveys do not always document whether children experience violent discipline by men who abuse women or by women who themselves experience abuse.

Global evidence about the magnitude of co-occurrence is complicated by the growing number of researchers, United Nations (UN) agencies and legal systems that define child exposure to intimate partner violence (by itself) as a form of child maltreatment, sometimes triggering mandatory reporting to child protection services (84), thereby posing challenges for service providers and women seeking help (15).

Intergenerational effects

Both VAW and VAC have intergenerational effects. Consequences of child maltreatment often last into adulthood, including long-term changes in brain structure, mental and physical health problems, risk behaviours, problems with social functioning, and reduced life expectancy (58, 85, 86).

VAW often has negative consequences for children. Violence during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of pre-term delivery and low birth weight (4, 87, 88). Partner VAW has been linked to higher rates of infant and under-five child mortality (89). Child exposure to intimate partner violence can have long-term health and social consequences similar to those of child abuse and neglect (84, 90).

Pathways by which partner violence affects child outcomes are not entirely understood. Marital conflict, family instability, and controlling behaviours – which often characterise families affected by partner violence – may contribute to child neglect, chronic stress, disrupted economic and social support, disrupted health care, and poor child health outcomes (91, 92). Some researchers theorise that children are negatively affected by abused mothers’ reduced maternal functioning due to stress, anxiety or depression (93); other studies produce mixed findings (94). Generally, researchers have paid less attention to poor parenting by men who abuse women (95), co-occurrence of child maltreatment (8), or batterers’ use of children as weapons against female partners, especially during separation and divorce (96, 97), despite the fact that using children to threaten and intimidate women has been part of conceptual models for understanding spousal abuse for more than 30 years (98). In fact, concern for children's safety is a reason why some women stay in abusive relationships and why others leave (99, 100).

Lastly, as noted earlier, research has found an association between exposure to violence in childhood (as a victim or witness) and the risk of experiencing or perpetrating violence during adolescence or adulthood, as documented in studies from high (101–103) and low and middle-income countries (104–106). Worldwide, women whose father beat their mother are significantly more likely to report partner violence than other women (40, 57). Similarly, multi-country studies from low and middle-income countries have found that men abused or neglected as children were significantly more likely than other men to report perpetrating physical or sexual VAW (45, 55, 56).

Common, cumulative, and compounding consequences

Violence against children, adolescents, and women may have similar consequences for physical health, mental health, and social functioning. Girls and women who experience sexual violence may experience similar sexual and reproductive health consequences, including unwanted pregnancy, pregnancy complications, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (107). In Swaziland, women who reported sexual violence before age 18 were significantly more likely to report STIs, pregnancy complications, miscarriages, unwanted pregnancy, and depression than respondents who did not report sexual violence, even after adjusting for age, community setting, socio-economic status, and orphan status (108).

Additionally, polyvictimisation – when individuals experience multiple forms of violence – may have cumulative or compounding effects (8). Evidence suggests that experiencing multiple forms of violence in childhood and adolescence (e.g. child maltreatment, exposure to partner violence against the mother, bullying, or dating violence) raises the risk of trauma and other negative health and social outcomes compared with experiencing just one form (109). Similarly, women who experience partner violence may be at heightened risk of negative mental and physical health outcomes if they have a history of childhood violence (110, 111).

Adolescence

The social constructs of ‘VAW’ and ‘VAC’ intersect at adolescence. The UN defines children to include boys and girls under 18 (2) and adolescents from age 10 to 19. Meanwhile, girls aged 15 and above are often considered ‘women’ by research and programmes focused on intimate partner violence, especially if they have married or had children (4). Violence against older adolescent girls aged 15–17 thus falls within the domains of both fields.

Adolescence is clearly a time of vulnerability, as both perpetration and victimisation of some forms of violence often begin or become elevated during this period. In many countries, a majority of adolescent survivors report first being sexually victimised between ages 15 and 19 (2). Similarly, a multi-country study from Asia and the Pacific found that a majority of adult men who ever committed rape carried out their first assault as teenagers (56), a finding echoed by studies from South Africa (65) and the USA (112). Meanwhile, physical and sexual violence are common within informal adolescent partnerships, as documented in high-income countries (113, 114) and in more limited research from low and middle-income countries such as Chile (115) and Mexico (116).

In addition, adolescent marriage and childbearing are risk factors for both intimate partner violence and child maltreatment. Worldwide, about one-fifth of adolescent girls are married or cohabiting with a male sexual partner (2). In many countries, married/cohabiting adolescent girls experience higher levels of recent partner violence than older women (40, 57), as do girls who begin childbearing as adolescents (39). Conversely, some evidence suggests that children of teenage mothers have a higher risk of child maltreatment than other children (20).

As the period between childhood and adulthood, research on violence against adolescents sometimes falls between the divide. International surveys on intimate partner violence, such as the DHS Domestic Violence Module, study women aged 15–49. While they gather some data on violence against adolescent girls, they typically lack study designs that allow in depth analyses of adolescent subsamples (117) or violence outside marital or cohabiting relationships. Meanwhile, internationally comparable evidence on VAC in low and middle-income countries remains limited (118), and important international surveys on children's wellbeing such as UNICEF's Multiple Indicator Surveys focus on violence and neglect against younger children rather than adolescents. Violence Against Children Surveys (VACS) gather a wide range of indicators on violence against adolescents – both boys and girls, but relatively few countries have done one, and most are not currently planning repeated data collection (42). In some cases, differences between conceptual frameworks used across the two bodies of research has produced conflicting definitions and gaps in the evidence, such as indicators for intimate partner violence against adolescent girls (13).

Discussion

Evidence of intersections has implications for programmes, policies, and research. First, overlapping correlates suggest that consolidating efforts to address shared risk factors may contribute to preventing both forms of violence. Both fields should have an interest in changing social norms that support violence and reducing harmful use of alcohol and drugs. In fact, associations between childhood exposure to violence and perpetrating or experiencing violence later in life are so strong that they suggest that prevention of violence in childhood may be essential for long-term prevention of VAW.

Both fields have identified school-based strategies as promising, particularly ‘whole school’ approaches that involve staff, students, and parents beyond the classroom (119, 120). Reviews of the programmatic literature suggest that some programmes that focus on corporal punishment or bullying lack attention to gender inequality and discrimination or the particular risks facing girls; others aim to prevent sexual violence against girls and women but overlook high levels of physical violence against boys (114, 121). Researchers have called for more understanding of how to integrate these approaches (21), particularly given mixed evidence of effectiveness (122).

Evidence that child maltreatment and intimate partner violence co-occur and produce intergenerational effects suggests a need for more integrated early intervention. In low and middle-income countries, home and community-based parenting programmes show promise for reducing harsh or abusive parenting (123) and may offer opportunities to address other forms of family violence. A few home visitation programmes in high-income countries have shown potential to reduce intimate partner violence as well as child maltreatment (124, 125). In sub-Saharan Africa, initiatives such as ‘One Man Can’ and ‘Families Matter!’ have integrated attention to gender inequality and partner violence within parenting programmes (126). Nonetheless, a systematic review concluded that parenting programmes in low and middle-income countries could do more to address gender inequality, son preference and discrimination against girls (33). Heise goes further, describing “an almost stunning” lack of attention to gender socialisation and inequality in most parenting curricula (25). Clearly this area needs more attention.

Co-occurrence and intergenerational effects also have important implications for health, social service, and legal responses to violence. Service providers from all sectors should be prepared to recognise and respond to multiple forms of violence within families. There is a need for more systematised evidence about best practices for collaboration between child protection services and services for women (127). Evidence suggests, for example, that mandatory reporting of child exposure to partner violence may overwhelm under-resourced child protection agencies (128, 129), create ethical challenges regarding patient confidentiality, and undermine women's willingness to seek help (130).

Co-occurrence poses particular challenges for health, social, and legal services and family courts (131). High-income countries such as Australia, Canada, and the USA have been criticised for ignoring or even penalising women seeking protection from spouses, or for accusing women of ‘failure to protect’ children from abusive partners (132, 133). In many low and middle-income countries, women have unequal rights to divorce, child custody, and property division (134), and children have even more limited access to legal protection. Generally, there is a need for more attention to co-occurrence in settings where legal systems discriminate against women, where customary laws operate alongside other legal systems, and where women's civil rights are in transition (135).

Evidence that different forms of violence have common and compounding consequences across the lifespan suggests a need for greater collaboration or at least knowledge sharing among those who provide services for adult, adolescent, and child survivors of abuse. Health services for survivors, including post rape care, need to be prepared to meet needs of different age groups as well as the compounding effects of polyvictimisation.

Adolescence falls between and within traditional domains of both fields and should be of interest to both. It is an age of elevated vulnerability to key forms of VAW and VAC, and a period when perpetration and experiences of some forms of VAW begin. It may also offer a window of opportunity for prevention. Both fields should have an interest in helping adolescent girls postpone unwanted sexual debut, marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing until adulthood. Child marriage (itself recognised as a harmful practice or form of violence against girls) and the partner violence that occurs in those unions should concern both fields. Helping adolescents manage risks and challenges is one of six strategies identified by UNICEF as important for preventing VAC (136), while those working on VAW have identified adolescence as an important life stage to influence attitudes and behaviours related to gender equality and violence (137).

Nonetheless, adolescents have sometimes been overlooked by child protection agencies that concentrate on younger children, and by researchers and programmes focused on women who are already married or cohabiting. Generally, violence against girls by non-cohabiting partners has been inadequately explored in low and middle-income countries.

The need to harmonise conceptual frameworks and instruments used to measure violence against adolescent girls may become particularly important as countries attempt to measure progress toward 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and targets, which contain two overlapping targets that relate to girls, namely target 5.2 (eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls) and 16.2 (end abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against and torture of children) (138).

Potential risks of greater collaboration

Greater coordination between the two fields may pose certain risks, and there may be valid reasons to work independently in some circumstances. Those working on VAC may be concerned that children's voices will not be heard or that integrated services will not meet their needs. Conversely, those working on VAW may be concerned that children's rights may be given precedence over women's rights and safety, as was the case with early programmes for preventing mother to child transmission of HIV (139), and may occur when providers are required to report partner violence to child protection agencies (133). There are also concerns about ensuring equitable investment in girls and boys, and adequate attention to gender equality within violence prevention programmes (140). These challenges deserve discussion but should not stop either field from seeking greater collaboration when appropriate.

Research gaps

Many knowledge gaps remain. We need to understand more about the cumulative effects of different forms of violence across the lifespan and what prevention strategies are effective in preventing multiple forms of violence across different settings (21). Understanding resiliency and how it moderates the impact of exposure to violence in childhood (49) is another important area of research, as is how to strengthen the availability and effectiveness of comprehensive services, particularly in low resource settings.

Limitations of this review

As noted earlier, given the size of the literature and the broad aim of the article, a systematic review and formal quality assessment of all sources was not feasible, though we relied on systematic reviews and meta-analyses when available. In fact, many intersections and sub-themes merit greater attention – including through systematic review, particularly in low and middle-income settings. We also did not explore the evidence of links among VAW, VAC, and other forms of violence, such as gang violence and armed conflict, another area of work that deserves more research (11).

Conclusion

This article highlights important intersections between VAW and VAC. While much of the literature focuses on intersections between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence, there are important intersections among other forms of violence, including sexual violence by non-partners. Evidence remains heavily weighted towards studies from high-income countries, but research from low and middle-income countries is growing and deserves investment.

Research, policies, and programmes that address one form of violence in isolation from others may overlook important vulnerabilities or misinterpret evidence about causes, correlates, and consequences. Evidence of intersections suggests opportunities for greater collaboration within school-based programmes, parenting interventions, and more coordinated health, social services, and legal responses. There is also a need for more coordination among researchers, especially as countries prepare to measure progress towards violence reduction as part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and targets. The positive news is the growing international political will to address VAW and VAC as impediments to human rights and sustainable development.

Acknowledgements

Deborah Billings and Jean Marie Place contributed to an earlier version of this paper. Betzabé Butrón, Theresa Kilbane, and Charlotte Watts commented on early drafts of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interests and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study. The Pan American Health Organization and the Know Violence in Childhood: Global Learning initiative (www.knowviolenceinchildhood.org/) provided support to authors for the preparation of this article but did not influence the content.

Disclaimer

Alessandra Guedes is a staff member of the Pan American Health Organization. The author alone is responsible for the views expressed in this publication, and they do not necessarily represent the decisions or policies of the Pan American Health Organization.

Paper context

Research and programmes on violence against women and violence against children have historically followed parallel but separate trajectories. With an emphasis on low and middle-income countries, this article reviews global evidence on intersections between these forms of violence, including shared risk factors, social norms, co-occurrence, intergenerational effects, consequences, and adolescence. Intersections between these forms of violence have important policy and programme implications and suggest a need for more collaboration between the two fields.

Authors’ contributions

Early drafts of this article were adapted from a keynote speech given by Alessandra Guedes at the Sexual Violence Research Initiative Forum, Evidence into action, 14–17 October 2013, Bangkok, Thailand. All authors contributed to the design, writing, and revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.UN. Report of the Secretary-General. New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2006. Ending violence against women: from words to action. In-depth study on all forms of violence against women. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF. Hidden in plain sight: a statistical analysis of violence against children. New York: UNICEF; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, Kress H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e2015407. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), Department of Reproductive Health and Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16:79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNFPA, UNICEF. Women's and children's rights: making the connection. New York: UNFPA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guedes A, Mikton C. Examining the intersections between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14:377–9. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.2.16249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Moylan CA. Intersection of child abuse and children's exposure to domestic violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9:84–99. doi: 10.1177/1524838008314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lessard G, Alvarez-Lizotte P. The exposure of children to intimate partner violence: potential bridges between two fields in research and psychosocial intervention. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;48:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercy J, Saul J, Hillis S. Research Watch. New York: UNICEF Office of Research; 2013. The importance of integrating efforts to prevent violence against women and children. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins N, Tsao B, Hertz M, Davis R, Klevens J. Connecting the dots: an overview of the links among multiple forms of violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alhusen JL, Ho GWK, Smith KF, Campbell JC. Addressing intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: challenges and opportunities. In: Korbin JE, Krugman RD, editors. Handbook of child maltreatment. Vol. 2. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- 13.TfG. Meeting Report. Washington, DC: Together for Girls (TfG) partnership; 2015. Priorities for research, monitoring and evaluation: building the new agenda for violence against children. [Google Scholar]

- 14.UN. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development; Resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015; New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hester M. The three planet model: towards an understanding of contradictions in approaches to women and children's safety in contexts of domestic violence. Br J Soc Work. 2011;41:837–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5:101–17. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heise L, Garcia Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia-Moreno C. Sexual violence. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 147–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Runyan D, Wattam C, Ikeda R, Hassan F, Ramiro L. Child abuse and neglect by parents and other caregivers. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulu E. A summary of the evidence and research agenda for what works: a global programme to prevent violence against women and girls. Pretoria, South Africa: Medical Research Council; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikton C. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Inj Prev. 2010;16:359–60. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinheiro PS. World report on violence against children: Secretary-General's study on violence against children. Geneva: United Nations; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gomez-Benito J. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse: a continuation of Finkelhor (1994) Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heise L. Working paper (version 2.0) London: STRIVE Research Consortium; 2011. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Alink LR. Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. Int J Psychol. 2013;48:81–94. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.697165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meinck F, Cluver LD, Boyes ME, Mhlongo EL. Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: a review and implications for practice. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16:81–107. doi: 10.1177/1524838014523336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tharp AT, DeGue S, Valle LA, Brookmeyer KA, Massetti GM, Matjasko JL. A systematic qualitative review of risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2013;14:133–67. doi: 10.1177/1524838012470031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Slep AM, Heyman RE, Garrido E. Child abuse in the context of domestic violence: prevalence, explanations, and practice implications. Violence Vict. 2008;23:221–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrahams N, Devries K, Watts C, Pallitto C, Petzold M, Shamu S, et al. Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: a systematic review. Lancet. 2014;383:1648–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340:1527–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, Musekiwa A, Zarowsky C. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knerr W, Gardner F, Cluver L. Parenting and the prevention of child maltreatment in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of interventions and a discussion of prevention of the risks of future violent behaviour among boys. Pretoria: Sexual Violence Research Initiative, Medical Research Council, and the Oak Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jejeebhoy S, Shah I, Thapa S, editors. Sex without consent: young people in developing countries. London: Zed Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.UNICEF. A statistical snapshot of violence against adolescent girls. New York: UNICEF; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulczycki A, Windle S. Honor killings in the Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review of the literature. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:1442–64. doi: 10.1177/1077801211434127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNICEF. Female genital mutilation/cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. New York: UNICEF; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milucci C. Harmful connections: examining the relationship between violence against women and violence against children in the South Pacific. Fiji: UNICEF Pacific; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bott S, Guedes A, Goodwin M, Mendoza JA. Violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean: a comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kishor S, Johnson K. Profiling domestic violence: a multi-country study. Calverton, MD: MEASURE DHS and ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen H, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sommarin C, Kilbane T, Mercy JA, Moloney-Kitts M, Ligiero DP. Preventing sexual violence and HIV in children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S217–23. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sumner SA, Mercy AA, Saul J, Motsa-Nzuza N, Kwesigabo G, Buluma R, et al. Prevalence of sexual violence against children and use of social services – seven countries, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:565–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fulu E, Warner X, Miedema S, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Lang J. Why do some men use violence against women and how can we prevent it? Quantitative findings from the United Nations multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok: UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women and United Nations Volunteers (UNV); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Contreras M, Heilman B, Barker G, Singh A, Verma R, Bloomfield J. Bridges to adulthood: understanding the lifelong influence of men's childhood experiences of violence analyzing data from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey. Washington, DC, Rio de Janeiro: International Center for Research on Women and Instituto Promundo; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadowski LS, Hunter WM, Bangdiwala SI, Munoz SR. The world studies of abuse in the family environment (WorldSAFE): a model of a multi-national study of family violence. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11:81–90. doi: 10.1080/15660970412331292306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson H, Ollus N, Nevala S. Violence against women: an international perspective. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Varcoe CM. Intimate partner violence in the family: considerations for children's safety. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:1186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wathen CN, MacGregor JC, Hammerton J, Coben JH, Herrman H, Stewart DE, et al. Priorities for research in child maltreatment. intimate partner violence and resilience to violence exposures: results of an international Delphi consensus development process BMC Public Health. 2012;12:684. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wathen CN, Macmillan HL. Children's exposure to intimate partner violence: impacts and interventions. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18:419–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Institute of Medicine. Forum on global violence prevention. Board on Global Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Preventing violence against women and children: workshop summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.UNICEF. Breaking the silence on violence against indigenous girls, adolescents and young women. New York: UNICEF, UN Women, UNFPA, ILO and the Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dartnall E, Loots L. Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI) Forum 2013: evidence into action; Conference report; Pretoria: SVRI, Medical Research Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fleming PJ, McCleary-Sills J, Morton M, Levtov R, Heilman B, Barker G. Risk factors for men's lifetime perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners: results from the international men and gender equality survey (IMAGES) in eight countries. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e187–207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jewkes R, Fulu E, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C. Prevalence of and factors associated with non-partner rape perpetration: findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e208–18. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, Devries K, Kiss L, Ellsberg M, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fry D, McCoy A, Swales D. The consequences of maltreatment on children's lives: a systematic review of data from the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13:209–33. doi: 10.1177/1524838012455873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.UNICEF. UNICEF global databases. New York: UNICEF; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.World Bank. Voice and agency: empowering women and girls for shared prosperity. Washington DC: World Bank Group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heise LL, Kotsadam A. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: an analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e332–40. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Global Initiative. Ending legalised violence against children: global progress to December 2015. London: Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children & Save the Children Sweden; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Bradley RH. Attitudes justifying domestic violence predict endorsement of corporal punishment and physical and psychological aggression towards children: a study in 25 low- and middle-income countries. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1208–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suarez E, Gadalla TM. Stop blaming the victim: a meta-analysis on rape myths. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:2010–35. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K. Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: findings of a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Cherry C, Jooste S, et al. Gender attitudes, sexual violence, and HIV/AIDS risks among men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. J Sex Res. 2005;42:299–305. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eisner M, Ghuneim L. Honor killing attitudes amongst adolescents in Amman, Jordan. Aggress Behav. 2013;39:405–17. doi: 10.1002/ab.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Population Council. Survey of young people in Egypt. Cairo: Population Council, West Asia and North Africa Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Violence against children in Kenya: findings from a 2010 national survey. Nairobi: UNICEF Kenya Country Office, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R. The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: a review and appraisal. J Fam Psychol. 1998;12:578–99. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chan KL. Children exposed to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence: a study of co-occurrence among Hong Kong Chinese families. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:532–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hunter WM, Jain D, Sadowski LS, Sanhueza AI. Risk factors for severe child discipline practices in rural India. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:435–47. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saed BA, Talat LA. Prevalence of childhood maltreatment among college students in Erbil, Iraq. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:441–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramiro LS, Madrid BJ, Brown DW. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:842–55. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rada C. Violence against women by male partners and against children within the family: prevalence, associated factors, and intergenerational transmission in Romania, a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen AC. Long-term effects of interparental violence and child physical maltreatment experiences on PTSD and behavior problems: a national survey of Taiwanese college students. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:148–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jirapramukpitak T, Harpham T, Prince M. Family violence and its ‘adversity package’: a community survey of family violence and adverse mental outcomes among young people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:825–31. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le MT, Holton S, Nguyen HT, Wolfe R, Fisher J. Poly-victimisation among Vietnamese high school students: prevalence and demographic correlates. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saile R, Ertl V, Neuner F, Catani C. Does war contribute to family violence against children? Findings from a two-generational multi-informant study in Northern Uganda. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dalal K, Lawoko S, Jansson B. The relationship between intimate partner violence and maternal practices to correct child behavior: a study on women in Egypt. J Inj Violence Res. 2010;2:25–33. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v2i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salazar M, Dahlblom K, Solorzano L, Herrera A. Exposure to intimate partner violence reduces the protective effect that women's high education has on children's corporal punishment: a population-based study. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24774. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24774. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.24774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gage AJ, Silvestre EA. Maternal violence, victimization, and child physical punishment in Peru. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:523–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN. Children's exposure to intimate partner violence. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:266–71. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Han A, Stewart DE. Maternal and fetal outcomes of intimate partner violence associated with pregnancy in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garoma S, Fantahun M, Worku A. The effect of intimate partner violence against women on under-five children mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ethiop Med J. 2011;49:331–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wood SL, Sommers MS. Consequences of intimate partner violence on child witnesses: a systematic review of the literature. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2011;24:223–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.DeRose L, Corcuera P, Gas M, Fernandez LCM, Salazar A, Tarud C. Family instability and early childood health in the developing world. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yount KM, DiGirolamo AM, Ramakrishnan U. Impacts of domestic violence on child growth and nutrition: a conceptual review of the pathways of influence. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1534–54. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McFarlane J, Symes L, Binder BK, Maddoux J, Paulson R. Maternal-child dyads of functioning: the intergenerational impact of violence against women on children. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:2236–43. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Renner LM, Boel-Studt S. The relation between intimate partner violence, parenting stress, and child behavior problems. J Fam Violence. 2013;28:201–12. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Greeson MR, Kennedy AC, Bybee DI, Beeble M, Adams AE, Sullivan C. Beyond deficits: intimate partner violence, maternal parenting, and child behavior over time. Am J Community Psychol. 2014;54:46–58. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9658-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bancroft L, Silverman J, Ritchie D. The batterer as parent: addressing the impact of domestic violence on family dynamics. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beeble ML, Bybee D, Sullivan CM. Abusive men's use of children to control their partners and ex-partners. Eur Psychol. 2007;12:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 98.McClennen J. Social work and family violence: theories, assessment, and intervention. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim JY, Lee JH. Factors influencing help-seeking behavior among battered Korean women in intimate relationships. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:2991–3012. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rasool S. Help-seeking after domestic violence: the critical role of children. J Interpers Violence. 2015;31:1661–86. doi: 10.1177/0886260515569057. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260515569057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Millett LS, Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Petra M. Child maltreatment victimization and subsequent perpetration of young adult intimate partner violence: an exploration of mediating factors. Child Maltreat. 2013;18:71–84. doi: 10.1177/1077559513484821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Narayan AJ, Englund MM, Egeland B. Developmental timing and continuity of exposure to interparental violence and externalizing behavior as prospective predictors of dating violence. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:973–90. doi: 10.1017/S095457941300031X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Widom CS, Czaja S, Dutton MA. Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:650–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Islam TM, Tareque MI, Tiedt AD, Hoque N. The intergenerational transmission of intimate partner violence in Bangladesh. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23591. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23591. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mandal M, Hindin MJ. Keeping it in the family: intergenerational transmission of violence in Cebu, Philippines. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mendoza JA, Bott S, Guedes A, Goodwin M. Intergenerational effects of violence against girls and women: selected findings from a comparative analysis of population-based surveys from 12 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. In: Dubowitz H, editor. World perspectives on child abuse. 10th ed. Aurora, CO: International society for prevention of child abuse and neglect; 2014. pp. 124–33. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Day K, Pierce-Weeks J. The clinical management of children and adolescents who have experienced sexual violence: technical considerations for PEPFAR programs. Arlington, Virginia: USAID; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reza A, Breiding MJ, Gulaid J, Mercy JA, Blanton C, Mthethwa Z, et al. Sexual violence and its health consequences for female children in Swaziland: a cluster survey study. Lancet. 2009;373:1966–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:149–66. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Montalvo-Liendo N, Fredland N, McFarlane J, Lui F, Koci AF, Nava A. The intersection of partner violence and adverse childhood experiences: implications for research and clinical practice. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36:989–1006. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1074767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lagdon S, Armour C, Stringer M. Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: a systematic review. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5:24794. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.White JW. Sexual assault perpetration and reperpetration: from adolescence to young adulthood. Crim Justice Behav. 2004;31:182–202. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Leen E, Sorbring E, Mawer M, Holdsworth E, Helsing B, Bowen E. Prevalence, dynamic risk factors and the efficacy of primary interventions for adolescent dating violence: an international review. Agress Violence Behav. 2013;18:159–74. [Google Scholar]

- 114.De Koker P, Mathews C, Zuch M, Bastien S, Mason-Jones AJ. A systematic review of interventions for preventing adolescent intimate partner violence. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lehrer JA, Lehrer EL, Koss MP. Sexual and dating violence among adolescents and young adults in Chile: a review of findings from a survey of university students. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.737934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rivera-Rivera L, Allen-Leigh B, Rodriguez-Ortega G, Chavez-Ayala R, Lazcano-Ponce E. Prevalence and correlates of adolescent dating violence: baseline study of a cohort of 7,960 male and female Mexican public school students. Prev Med. 2007;44:477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Way A. DHS Occasional Paper No. 9. Rockville, MD: ICF International; 2014. Youth data collection in DHS surveys: an overview. [Google Scholar]

- 118.CPMERG. Measuring violence against children: inventory and assessment of quantitative studies. New York: Division of Data, Research and Policy, UNICEF; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Devries KM, Knight L, Child JC, Mirembe A, Nakuti J, Jones R, et al. The good school toolkit for reducing physical violence from school staff to primary school students: a cluster-randomised controlled trial in Uganda. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e378–86. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00060-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.DevTech Systems Inc. Safe schools program final report. Washington, DC: USAID; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Leach F, Dunne M, Salvi F. A global review of current issues and approaches in policy, programming and implementation responses to school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) for the education sector. Paris: UNESCO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Walsh K, Zwi K, Woolfenden S, Shlonsky A. School-based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD004380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004380.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Knerr W, Gardner F, Cluver L. Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Prev Sci. 2013;14:352–63. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Prosman GJ, Lo Fo Wong SH, van der Wouden JC, Lagro-Janssen AL. Effectiveness of home visiting in reducing partner violence for families experiencing abuse: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2015;32:247–56. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bair-Merritt MH, Jennings JM, Chen R, Burrell L, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, et al. Reducing maternal intimate partner violence after the birth of a child: a randomized controlled trial of the Hawaii Healthy Start Home Visitation Program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:16–23. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.TfG. From research to action: advancing prevention and response to violence against children; Report on the global violence against children meeting; May 2014; Ezulwini, Swaziland. Washington, DC: Together for Girls (TfG) Partnership; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Turner W, Broad J, Drinkwater J, Firth A, Hester M, Stanley N, et al. Interventions to improve the response of professionals to children exposed to domestic violence and abuse: a systematic review. Child Abuse Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1002/car.2385. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/car.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Edleson JL, Gassman-Pines J, Hill MB. Defining child exposure to domestic violence as neglect: Minnesota's difficult experience. Soc Work. 2006;51:167–74. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cross TP, Mathews B, Tonmyr L, Scott D, Ouimet C. Child welfare policy and practice on children's exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:210–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lewis N. Balancing the dictates of law and ethical practice: empowerment of female survivors of domestic violence in the presence of overlapping child abuse. Ethics Behav. 2003;13:353–66. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hayes A, Higgins D, editors. Families, policy and the law: selected essays on contemporary issues for Australia. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Meier J. Domestic violence, child custody, and child protection: understanding judicial resistance and imagining the solutions. J Gend Soc Pol Law. 2003;11:657–730. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Humphreys C, Absler D. History repeating: child protection responses to domestic violence. Child Fam Soc Work. 2011;16:464–73. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hudson VM, Bowen DL, Nielsen PL. What Is the relationship between inequity in family law and violence against women? Approaching the issue of legal enclaves. Polit Gend. 2011;7:453–92. [Google Scholar]

- 135.UNWOMEN. Summary report: the Beijing declaration and platform for action turns 20. New York: UN Women; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 136.UNICEF . Ending violence against children: six strategies for action. New York: UNICEF; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: evidence from programme interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 138.United Nations. Report of the inter-agency and expert group on sustainable development goal indicators. New York: United Nations Economic and Social Council; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gruskin S, Ahmed S, Ferguson L. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling in health facilities – what does this mean for the health and human rights of pregnant women? Dev World Bioeth. 2008;8:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Reed E, Raj A, Miller E, Silverman JG. Losing the ‘gender’ in gender-based violence: the missteps of research on dating and intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2010;16:348–54. doi: 10.1177/1077801209361127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]