Abstract

Introduction

One Health (OH) can be considered a complex emerging policy to resolve health issues at the animal–human and environmental interface. It is expected to drive system changes in terms of new formal and informal institutional and organisational arrangements. This study, using Rift Valley fever (RVF) as a zoonotic problem requiring an OH approach, sought to understand the institutionalisation process at national and subnational levels in an early adopting country, Kenya.

Materials and methods

Social network analysis methodologies were used. Stakeholder roles and relational data were collected at national and subnational levels in 2012. Key informants from stakeholder organisations were interviewed, guided by a checklist. Public sector animal and public health organisations were interviewed first to identify other stakeholders with whom they had financial, information sharing and joint cooperation relationships. Visualisation of the OH social network and relationships were shown in sociograms and mathematical (degree and centrality) characteristics of the network summarised.

Results and discussion

Thirty-two and 20 stakeholders relevant to OH were identified at national and subnational levels, respectively. Their roles spanned wildlife, livestock, and public health sectors as well as weather prediction. About 50% of national-level stakeholders had made significant progress on OH institutionalisation to an extent that formal coordination structures (zoonoses disease unit and a technical working group) had been created. However, the process had not trickled down to subnational levels although cross-sectoral and sectoral collaborations were identified. The overall binary social network density for the stakeholders showed that 35 and 21% of the possible ties between the RVF and OH stakeholders existed at national and subnational levels, respectively, while public health actors’ collaborations were identified at community/grassroots level. We recommend extending the OH network to include the other 50% stakeholders and fostering of the process at subnational-level building on available cross-sectoral platforms.

Keywords: One Health, stakeholder, institutionalisation, Kenya

Infectious diseases are likely to continue emerging and re-emerging in the foreseeable future, with profound negative impacts on multiple sectors and global economies (1). Zoonoses account for 70% of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) and 60% of human pathogens/diseases (2–4). About 80% of human infectious disease pathogens could be used for bioterrorism (5). Major zoonotic EIDs that have occurred over the last 20 years include bovine spongiform encephalopathy, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), severe acute respiratory syndrome (6), Hendra virus disease (7), Nipah virus encephalitis (8), West Nile fever (9), pandemic H1N1 influenza (10), Middle East respiratory syndrome (11) and Ebola (12). Apart from the EIDs, endemic zoonoses such as Rift Valley fever (RVF) are also of great concern.

To mitigate the worrying trend of EIDs, the One Health (OH) strategy is expected to gain momentum as a tool to address both associated multisectoral impacts and environmental, animal and human health drivers for their emergence and spread. Major drivers for (re-)emergence of pathogens include increased movements and contacts of people, wildlife and livestock; intensification of livestock production; and low biosecurity in farms and live animal or wet markets (13–15). A main driver of RVF is climate change where El Nino events influence the frequency of outbreaks.

The OH strategy places health issues in a broader developmental and ecological context through collaborative efforts among multiple disciplines and sectors to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment (16–18). Promotion of OH seeks to put into best use limited resources available to health sectors, which may not be achieved through single-sector approaches and should add value in financial savings, improved health and well-being of people and animals, and fostered environmental services (19).

Protocols to implement OH strategy include establishment of cross-sectoral (partnerships across sectors) and multidisciplinary committees, joint planning and implementation of multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral approaches, development of communities’ capacities to report and timely response, creation and strengthening of multidisciplinary networks, developing appropriate university curricula and continuous training, and proactive disease risk management practices that address disease drivers (17, 18, 20–23). In summary, OH can be considered a complex innovation to identified health problems at human, animal and environmental interfaces. It is expected to drive changes in institutional (formal and informal) and organisational arrangements. To better understand and guide national institutionalisation processes, this paper presents a comprehensive stakeholder and institutional analysis within a broader study on RVF in an early OH adopting country – Kenya. The disease has been identified as a problem that requires OH approach (24).

Materials and methods

Conceptual framework for OH institutional analysis

We conceptualised OH as a policy or institutional innovation whose institutionalisation process analysis requires a socio-ecological approach. We assumed the process starts with identification of a need for all stakeholders to coordinate and cooperate on cross-sectoral health issues. Of the three modes of economic coordination – hierarchies, markets, and networks (25) – the latter was taken as most appropriate for bringing together OH stakeholders. Development of OH stakeholder or actor–networks to facilitate cross-sectoral collaboration may require significant system change across sectors with already existing hierarchies. Actor–network theory (ANT) and Social network analysis (SNA) provide a theoretical and analytical framework for understanding and guiding successful policy or innovation in complex systems that require network building (26).

ANT focuses on science-based innovation processes and provides insights into people, research evidence, technologies, financial resources, institutions and regulations required to drive innovations. On the other hand, SNA provides insights into social diffusion and adoption of innovations and coalition formation (27). We consider all actors within OH as stakeholders and thus use the terms interchangeably.

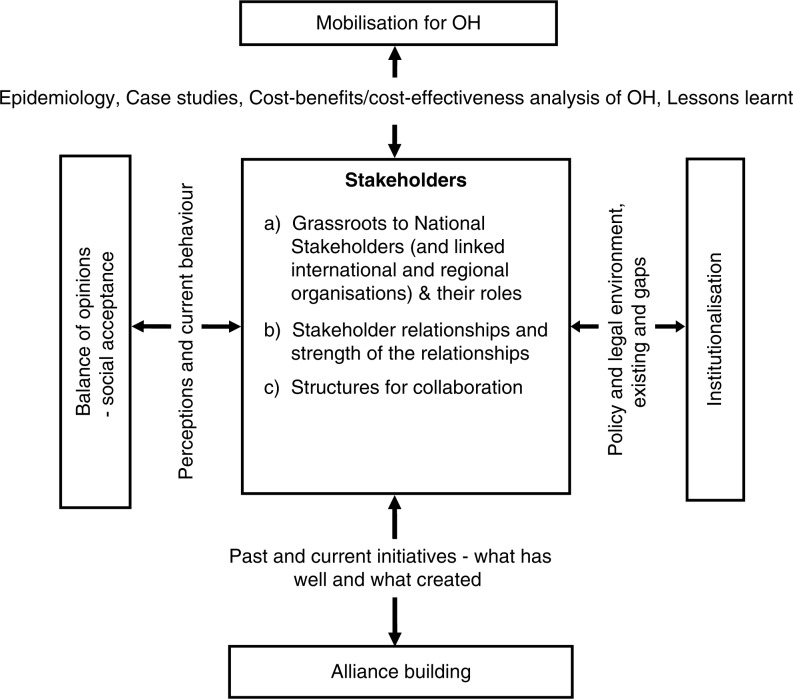

Figure 1 shows this study's schematised five-component conceptual framework for OH institutionalisation adapted from Ref. (26). The key and central component focuses on stakeholders and their existing (and missing) relationships, which would be required to initiate and institutionalise OH. The SNA widely used to study social networks of stakeholders was therefore the key analytical method of the central component. In OH adoption, stakeholders would not only initiate multisectoral cooperation on cross-sectoral health issues but also organise and hold in place activities of the other four components (mobilisation, social acceptance, alliance building, and institutionalisation). In doing so, they are guided by policy and legal frameworks. In the absence of appropriate policies, the stakeholders can also influence policy and legal frameworks. Mobilisation, a dynamic interplay between evidence and arguments (26), would shape and define how OH actions and solutions are framed. Stakeholders’ current perceptions and the provided evidence would influence the actions and solutions. OH policy works if key stakeholders gather cross-sectoral allies (and their resources) to join a network based on empirical evidence and benefits associated with change. However, the evidence is a cultural construct. Although there are scientific principles across nations, there might be a strong cultural influence on what is acceptable as evidence. Often, stakeholders may focus on a common problem that requires OH approach. Social acceptance process requires buy-in by governments and other actors. Institutionalisation refers to the process by which authoritative acceptance and institutional support emerges with appropriate governance structures (e.g. professional associations and issue-specific government units or committees) and financing and development of appropriate policy frameworks.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework for One Health (OH) institutional analysis.

To implement the framework, we choose a common problem in Kenya that requires OH-the RVF epidemics and therefore mapped: RVF and OH stakeholder landscape; existing and missing networks (relationships); institutions or platforms for cross-sectoral and multidisciplinary collaborations; past and current related mobilisation to institutionalisation activities; and supporting policies and legal frameworks.

Study area, data, and sampling techniques

Primary and secondary data were collected at two levels 1) Nairobi County–based national or head offices of stakeholder organisations and 2) subnational province and district-based organisations in Garissa County in north-eastern Kenya. The two levels represented decision-making (policy and technical) and policy implementation, respectively. Subnational analysis also considered community level, where livestock keepers interfaced with the animal and public health services. Subnational data were collected in February 2011 while national data were collected between February 2011 and January 2012. However, updating of institutional set-up continued up to 2014. Garissa County was selected since it was a hotspot for the 1997/98 and 2006/07 human and animal RVF outbreaks.

Data collected included: stakeholder roles in RVF and OH-related activities; collaborating partners; types of relationships; strength of relationships (also asking for explicitly perceived missing relationships), past and current cross-sectoral cooperation and coordination initiatives, structures and projects used, and, relevant policies and legal frameworks supporting OH.

A snowball method of stakeholder mapping and SNA described in (29) was used. The method rarely draws samples as was the case for this study. Based on prior knowledge, the Department of Veterinary Services (DVS), Ministries in charge of Health (MOH), and livestock keepers were identified as key stakeholders (egos) for RVF and OH, and were chosen as the starting (snowballing) points to identify other stakeholders and core groups. Key informants from DVS and MOH were identified and interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. Seventy-two livestock keepers were interviewed in four group discussions held in four villages (Fafi, Garissa, Bura, and Balambala), randomly selected from the 10 that key informants identified as most affected during the RVF epidemic in 2007.

Snowballing from these three stakeholders determined the sample reached of 63 key informants, 35 from national stakeholder organisations and 28 drawn from community animal and public health workers, public sector livestock and public health service providers, non-governmental organisations, programmes, and livestock traders. While prior listing of all possible OH relevant organisations based on prior knowledge and literature review was undertaken, it mainly assisted in identifying stakeholders who had no relationships with those interviewed.

Based on SNA (27), we characterised relationships between the stakeholders. Three relationships were considered: financial resources flows, cooperation (joint planning and implementation), and information sharing. Strengths of the three relationships were measured by asking respondents to assign individual qualitative scores using grouped ordinal and interval approaches. They were asked to describe frequency (as high, medium, low, or not applicable) and intensity (as high, medium, low, or not applicable) of the relationships and based on both, they scored each as either non-existent, weak, medium, strong, or very strong. Often, as noted in (29), respondents experienced difficulties scoring each relation independently and were allowed to collapse the three and use one score instead. To construct some true interval-level measure, we converted the qualitative scores into quantitative values using a scale of 0–8 as in no linkage (0), weak (1 or 2), medium (3 or 4), strong (5 or 6), and very strong (7 or 8). The decision to assign a lower or higher score for, let us say, medium was based on described frequency and intensity of interactions. The approach to an extent balanced the predispositions of the researcher and the respondent's descriptions, whereas the continuous measure of the relationships allowed estimation of statistical measures. The quantitative scores were plotted in a matrix. UCINET software (30) generated SNA sociograms and statistical measures (density, clustering coefficients, degree of closeness, and between-ness) of relationship strength. The statistical measures were estimated to understand the extent of relationships, and stakeholder power and influence within the OH network. Centrality statistics of actor degree, closeness (or farness), and between-ness reflect power and influence within the network. Degree measures describe the way an actor is embedded in a network while closeness refers to how close they are to others. High in-degree values for a stakeholder reflect a position where others want to influence it, for example, through information sharing. High out-degree measure for a stakeholder reflects a position of where it wants to influence those linked to them. Between-ness refers to a position of an actor in a network as in between several pairs of actors, or no other actors lie between them and other actors. The degree of clustering (cluster coefficient) of stakeholders in a network is estimated as an average of all the neighbourhoods.

To generate sociograms or visual diagrams of the network, the interval data were binarised where scores 0 and 1–8 were coded as absent ‘0’ and present ‘1’, respectively.

Results and discussions

Subnational stakeholders, roles, mobilisation, and network properties

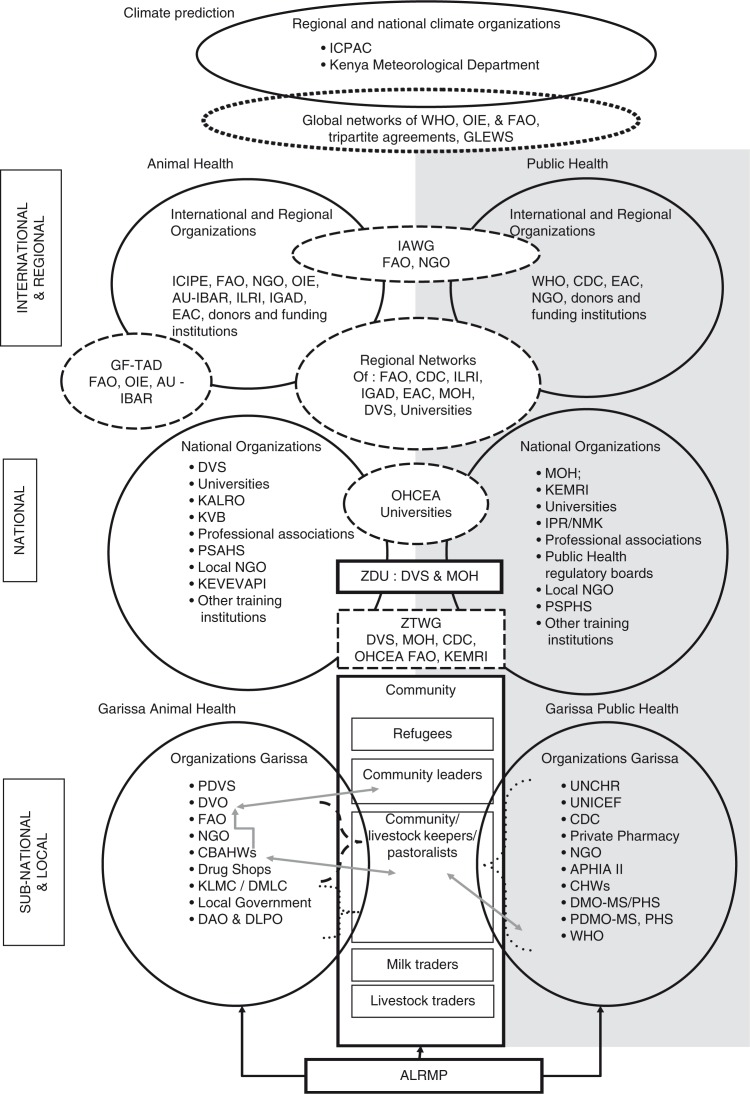

In Garissa County, 20 stakeholder organisations or groups relevant to OH included public and private service providers, livestock keeping community who were pastoralists with linked institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), United Nations technical agencies, traders, and three programmes/projects (Fig. 2; subnational component). In this study, we classified a stakeholder as an NGO if it was non-profit, funded by donors to support animal or public health except research and were not linked to any government or United Nations.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of RVF and OH stakeholders and coordination/cooperation structures. ALRMP, Arid Lands Resource Management Programme; APHIA II, AIDS, Population and Health Integrated Assistance Program; AU-IBAR, African Union Inter Bureau of Animal Resources; CBAHW, Community-Based Animal Health Workers; CDC, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; CHW, Community Health Workers; DAO & DLPO, District Agriculture Officer & District Livestock Production Officer; DMO-MS/PHS, District Medical Officers, Medical Services/Public Health and Sanitation; DVO, District Veterinary Officer; DVS, Department of Veterinary Services; EAC, East African Community; FAO, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations; GF-TAD, Global Framework for Transboundary diseases; GLEWS, Global Early Warning System; IAWG, Interagency Working Group; ICIPE, International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology; ICPAC, IGAD Climate Predictions and Applications Centre; IGAD, Inter Governmental Authority on Development; ILRI, International Livestock Research Institute; IPR/NMK, Institute of Primate Research of the National Museums of Kenya; KALRO, Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation; KEMRI, Kenya Medical Research Institute; KEVEVAPI, Kenya Veterinary Vaccines Production Institute; KLMC/DMLC, Kenya/District Livestock Marketing Council; KVB, Kenya Veterinary Board; MOH, Ministries in charge of Health; NGO, Non-Governmental Organisations; OHCEA, One Health Central and East Africa Network; OIE, World Organisation for Animal Health; PDMO-MS & PHS, Provincial Medical Officer Medical Services and Public Health and Sanitation; PDVS, Provincial Director of Veterinary Services; PSAHS, Private Sector Animal Health Service; PSPHS, Private Sector Public Health Service; UNHCR, United Nations High Commission for Refugees; UNICEF, United Nations Children Education Fund; WHO, World Health Organization; ZDU, Zoonotic Disease Unit; ZTWG, Zoonotic Technical Working Group.

Pastoralists perceived their roles as that of reporting animal disease outbreaks, treatment of sick animals, seeking public health care, and compliance with control or risk reduction measures. The District Veterinary Officers (DVOs) and their teams described their role as that of implementing animal health prevention and control measures. District Medical Officers (DMOs) described their role as that of coordinating delivery of public health services through a network of health facilities. Respondents consistently pointed to inadequate capacities of the DVOs, DMOs and pastoralists to effectively play their respective roles. Main barriers to effective roles mentioned by the stakeholders included inadequate government funding, personnel and other logistics, unfavourable animal health policies, weak interface between pastoralists and service providers, pastoralists’ knowledge capacity, increased vulnerability to shocks, and low incentives for livestock keepers to report animal diseases. They attributed the low incentives to difficulties in accessing the veterinary services. They described public health services as generally inadequate but more accessible compared to animal health services. The other subnational stakeholders described their roles as provision of information and resources to public animal and public health sectors (DVOs and DMOs) and communities in addition to direct implementation of complementary activities to improve health.

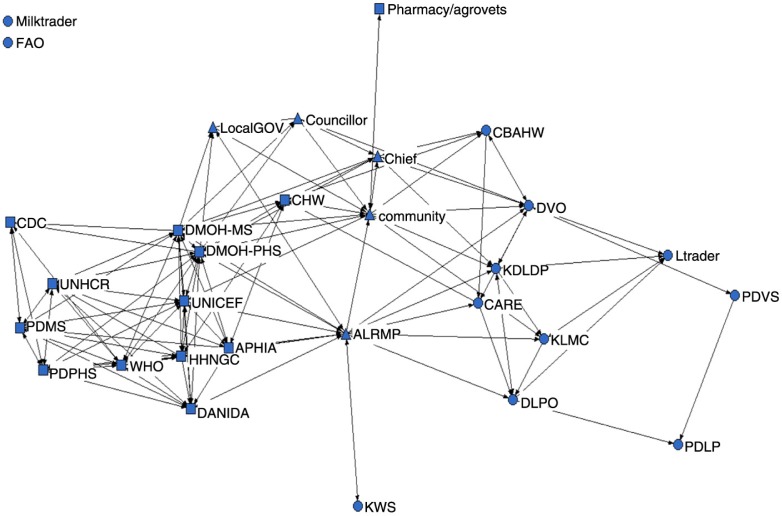

Subnational network sociogram (Fig. 3) demonstrates how the different stakeholders related. The computed overall binary network density was 0.21, which implied that only 21% of the possible ties were present. The sociogram is dense around the public health stakeholders and less dense around animal health stakeholders. Two livestock stakeholders (FAO and milk traders) had no relationships with the rest of the stakeholders, while DVO and the local wildlife office had no link. Only two coordination platforms enhanced cooperation amongst sectors and stakeholders. These included 1) a multisectoral district steering group (DSG) supported by a donor-funded cross-sectoral development project: the Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMP). The DSG had established a public health subgroup (HSG); 2) Public health stakeholder forums at all levels of health facilities. Health facilities had established health committees at community level.

Fig. 3.

Sociograph of the Garissa County OH network. Key: square (public health), circle (animal health), and upward triangle (others). ALRMP, Arid Lands Resource Management Programme; APHIA, AIDS, Population and Health Integrated Assistance Program; CARE, CARE International in Kenya; CBAHW, Community-Based Animal Health Workers; CDC, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; CHW, Community Health Workers; DANIDA, The Danish International Development Agency; DLPO, District Livestock Production Officers; DMOH-MS, District Medical Officers of Health Medical Services; DMOH-PHS, District Medical Officers of Health Public Health Services; DVO, District Veterinary Officers; FAO, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations; HHNGO, Human Health Non Governmental Organisation; KDLDP, Kenya Drylands Livestock Development Program; KLMC, Kenya Livestock Marketing Council; KWS, Kenya Wildlife Service; Ltrader, Livestock Trader; PDLP, Provincial Director of Livestock Production; PDPHS, Provincial Director of Public Health and Sanitation; PDMS, Provincial Director of Medical Services; PDVS, provincial Director of Veterinary Services; UNHCR, United Nations High Commission for Refugees; UNICEF, United Nations Children Education Fund; WHO, World Health Organization.

The DSG comprised of all district public sector heads, NGOs, and private sector organisations. Its main function was coordination of development activities including response to multisectoral emergencies such as RVF outbreaks. The ALRMP's drought monitoring or early warning officers collected household and community-level information that included disease status in animals and people. The local office of World Health Organization (WHO) analysed the public health information to share with local public health heads. Joint public and animal health activities were rare. The HSG coordinated only public health issues, though DVOs were invited to the meetings. The community-based public health facility committees brought together community leaders, community health workers (CHWs), and health officers for the purposes of enhancing community participation in health management and disease reporting. The public health platforms provided opportunities for private sector to engage and support public health services. There were more public health actors (including NGOs) compared to livestock or animal health. Livestock and animal health stakeholders had no sectoral collaboration platforms amongst themselves, with livestock keepers and public health sectors.

The degree centrality measures (Table 1) of the subnational network agree with the description of the collaborations mentioned above. The public health actors, ALRMP, and the community had more relationships and more pairs compared to livestock or animal health actors (Table 1, column 3, figures in brackets). Between-ness centrality measures of 239 (in) and 32 (out) identified the ALRMP as the actor who linked clusters, acted as broker, and has highest power within the network. This was attributed to the DSG and HSG collaboration platforms and the fact that the project was addressing issues in multiple sectors. Other stakeholders who linked clusters included the DVOs, community, WHO, and the Ministry of Health (MOH). Also, the ALRMP emerged as the actor demonstrating the highest in and out closeness at 23 and 29, respectively, followed by the MOH (22, 29), WHO (21, 27), and other human health NGOs (21, 26). For the same network, degree centrality measures confirm that the public health actors, ALRMP and the community, had more ties compared to livestock/animal health actors. The MOH had strong linkages to other public health stakeholders, ALRMP and the community, while the DVO had weak linkages with very few actors in the livestock or animal health sector.

Table 1.

Centrality statistics measures for Garissa County stakeholders

| Degree | Farness | Closeness | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acronym | Actor | Cluster coefficient | In | Out | In | Out | In | Out | Between | nBetween |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees | 0.92 (36) | 9 | 8 | 147 | 120 | 20 | 24 | 1 | 0.1 |

| DANIDA | The Danish International Development Agency | 0.84 (45) | 10 | 9 | 137 | 110 | 21 | 26 | 14 | 2 |

| CDC | Centre for Disease Control | 0.80 (10) | 5 | 3 | 151 | 132 | 20 | 22 | 0.2 | 0.03 |

| PDMS | Provincial Director of Medical Services | 0.78 (36) | 9 | 9 | 147 | 121 | 20 | 24 | 5 | 1 |

| PDPHS | Provincial Director of Public Health and Sanitation | 0.78 (36) | 9 | 9 | 147 | 119 | 20 | 24 | 6 | 1 |

| HHNGO | Human Health NGOs | 0.76 (55) | 8 | 11 | 138 | 108 | 21 | 27 | 19 | 2 |

| APHIA | AIDS, Population and Health Integrated Assistance Program | 0.75 (55) | 10 | 11 | 144 | 108 | 20 | 27 | 12 | 1 |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund | 0.74 (55) | 10 | 9 | 143 | 110 | 20 | 26 | 12 | 2 |

| WHO | World Health Organisation | 0.74 (55) | 11 | 11 | 136 | 108 | 21 | 27 | 35 | 4 |

| Local government | 0.65 (10) | 4 | 2 | 143 | 121 | 20 | 24 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Councillors | 0.57 (15) | 3 | 3 | 146 | 126 | 20 | 23 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| KLMC | Kenya Livestock Marketing Council | 0.55 (10) | 4 | 3 | 144 | 123 | 20 | 24 | 17 | 2 |

| CBAHW | Community-Based Animal Health Workers | 0.55 (10) | 3 | 4 | 153 | 122 | 19 | 24 | 4 | 1 |

| Livestock traders | 0.50 (6) | 4 | 2 | 158 | 142 | 18 | 20 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| CHW | Community Health Workers | 0.45 (28) | 7 | 6 | 143 | 115 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 2 |

| DMOH-PHS | District Medical Officer of Health – Public Health and Sanitation | 0.43 (105) | 12 | 15 | 132 | 102 | 22 | 28 | 74 | 9 |

| DMOH-MS | District Medical Officer of Health – Medical Services | 0.43 (105) | 12 | 14 | 132 | 104 | 22 | 28 | 61 | 8 |

| KDLDP | Kenya Drylands Livestock Development Program | 0.43 (21) | 6 | 5 | 140 | 117 | 21 | 25 | 31 | 4 |

| Chief | 0.41 (28) | 7 | 6 | 140 | 110 | 21 | 26 | 34 | 4 | |

| DLPO | District Livestock Production Officer | 0.37 (15) | 4 | 4 | 146 | 122 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 3 |

| CARE | CARE International in Kenya | 0.35 (10) | 3 | 4 | 147 | 116 | 20 | 25 | 6 | 1 |

| ALRMP | Arid Lands Resource Management Project | 0.28 (105) | 14 | 13 | 129 | 101 | 23 | 29 | 259 | 32 |

| DVO | District Veterinary Officer | 0.24 (36a) | 7 | 8 | 139 | 113 | 21 | 26 | 84 | 10 |

| Community | 0.30 (78) | 7 | 10 | 139 | 106 | 21 | 27 | 92 | 11 | |

| Milk traders | (0) | 0 | 0 | 870 | 870 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organisation | (0) | 0 | 0 | 870 | 870 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| KWS | Kenya Wildlife Service | (0) | 1 | 1 | 154 | 127 | 19 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Pharmacy/Agro Vets | (0) | 1 | 1 | 164 | 132 | 17 | 22 | 0 | 0 | |

| PDVS | Provincial Director of Veterinary Services | (1) | 1 | 2 | 164 | 137 | 18 | 21 | 3 | 0.4 |

| PDLP | Provincial Director of Livestock Production | (1) | 2 | 0 | 139 | 870 | 21 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean, n=30 | 6 (3.9) | 6 (4.4) | 193 (181) | 193 (226) | 19 (4.3) | 23 (7) | 27 (50) | 3.4 (6.2) | ||

Number in brackets refer to the number of pairs.

National-level stakeholders, roles, mobilisation activities, and network properties

A total of 32 international, regional, and national public and private sector organisations relevant to RVF and OH issues were identified at national level (Fig. 2). They can be grouped into four sectors: livestock, wildlife, public health, and environment (climate prediction agencies). Majority (21; 65%) were national organisations, of which 11 addressed animal health, 9 concerned public health, and 1 (the Kenya Meteorological Department (KMD)) worked on climate prediction issues. Eleven representing a third were international or regional organisations, based in Nairobi.

Activities of the national organisations included regulation and policy setting, delivery of services, academic, research, training, and regulatory and professional organisations. The DVS, the two MOH, and Kenya Wildlife Services were the lead agencies (mandate provision described in law) in livestock health, public health, and wildlife RVF-related OH issues, respectively. On the other hand, the roles of the international and regional organisations included 1) financial and technical support to the national organisations, 2) regional coordination of respective health activities through donor-funded sectoral or cross-sectoral initiatives, networks, and projects.

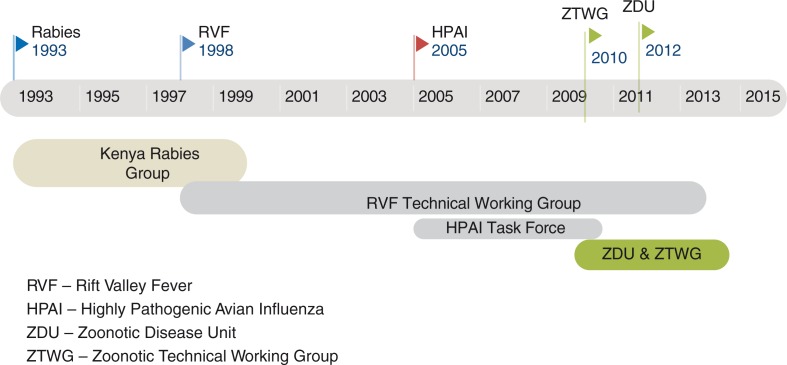

Current and past initiatives towards mobilisation, alliance building, social acceptance, and institutionalisation of OH at national level are summarised in Fig. 4. Three zoonotic diseases (rabies, RVF, and HPAI) drove the initiatives. The process was triggered by the formation of a regional network for rabies – Southern and Eastern African Rabies Group (SEARG) – in the early 1990s. The network called for the formation of national rabies groups. Twelve scientists/technical officers drawn from DVS, MOH, and other animal and human health institutions started an informal platform and named it the Kenya Rabies Group (KRG) in 1993. The group's activities included collection and sharing of rabies information used to advocate for both joint control efforts and increased resource allocation. The efforts led to a 440% rise in allocation of rabies control funds in 1997/98 and increased private sector participation in the control. However, the activities were not sustained and ceased in 2000, attributed to failures in alliance building and social acceptance by the heads of the institutions involved. Other factors cited included re-deployment of founding members and imbalanced composition as animal health experts accounted for 83% of KRG members. As a result, funding for rabies dropped by 92% in 2001 despite a focal person based at DVS maintaining a link to SEARG.

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram of national-level OH institutionalisation process in Kenya. HPAI, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza; RVF, Rift Valley Fever; ZDU, Zoonotic Disease Unit; ZTWF, Zoonotic Technical Working Group.

Some members of the KRG and other scientists formed a second informal platform, namely, the multisectoral and multidisciplinary RVF scientific working group (RVF-SWG) after the 1997/98 RVF epidemic. Their activities focused on RVF research and generation of evidence. When the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) predicted the next RVF epidemic in 2006/2007, the group technically supported multisectoral response efforts and had continued to do so in the post-epidemic period. The 15-year plus continuity of the group was largely attributed to both support by CDC (showing that institutional support is critical) and increased prioritisation of RVF in the country.

Formal process to institutionalise OH begun with a HPAI multisectoral taskforce formed in late 2005 after recommendations from FAO and WHO. Through the taskforce, technical heads of veterinary and medical services mobilised and built alliances with many OH stakeholder organisations in preparation for an influenza pandemic. However, in 2007, an RVF epidemic occurred and the multisectoral taskforce and RVF-SWG joined hands to support and coordinate the response. In 2010, noting usefulness of the HPAI taskforce in zoonoses control, policy makers transformed the taskforce into a Zoonotic Technical Working Group (ZTWG) and established a joint animal and public health Zoonotic Disease Unit (ZDU) in 2012. The institutionalisation activities have been largely funded by Centre for Disease Control (CDC) and line ministries. The period also coincided with the FAO/OIE/WHO calls for national OH platforms. By mid-2014, ZTWG and ZDU had identified priority zoonoses; developed a 5-year strategic plan; updated RVF's contingency plan; implemented joint zoonoses surveys and investigations; and were developing OH strategies for rabies and brucellosis.

Two policies guided animal and public health – a draft Veterinary Policy and the Kenya Public Health Policy 2012–2030. The draft Veterinary Policy explicitly had a policy statement mentioning that the two health sectors will establish cooperation platforms. On the other hand, the Kenya Public Health Policy 2012–2030 adopted a wider policy objective of strengthening collaboration with other sectors that impact on health.

In 2010, the ZTWG membership was drawn from 17 (53%) out of the 32 identified national stakeholders of which 35% had roles in public health, 29% in livestock, 12% in wildlife health, and 24% in cross-sectoral thematic areas. Missing stakeholder groups included: private sector service providers, NGOs, donors, regulatory and professional associations. Disciplinary orientation of ZTWG showed dominance (of 74%) by medical or veterinary epidemiologists and public health experts, making it a multidisciplinary team of two disciplines (veterinary and medical health professionals).

Among the regional and international organisations, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of The United Nations (FAO), CDC, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and WHO supported the ZDU and ZTWG and also engaged in regional coordination of OH. The African Union-Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR) implemented OH-related projects and was in the process of establishing a regional coordination mechanism. The two centres of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development's (IGAD) – Climate Predictions and Applications Centre (ICPAC) and Centre for Pastoral and Livestock Development (ICPALD) mostly provided livestock early warning and climate data. The NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre is a key information source for RVF. They had predicted the 2006–2007 outbreaks 1–2 months prior to the first human cases (31).

Regional networks to which the international or regional organisations belonged were noted as they either are or will provide an opportunity to link the national networks to regional and global initiatives. Two main global networks were 1) the FAO, OIE and WHO's Global Early Warning System (GLEWS) for major animal diseases and 2) the FAO and OIE's (plus AU-IBAR in Africa) Global framework for the progressive control of transboundary animal diseases (GF-TADs). Regional networks mentioned by stakeholders included:

Nairobi-based multisectoral Interagency Working Group (IAWG) on disaster preparedness, which had previously established on ad hoc basis multisectoral subgroups addressing avian influenza and RVF.

Nine regional networks supported by the international, regional stakeholders as well as donors that include the Cysticercosis Working Group for Eastern and Southern Africa (CWGESA).

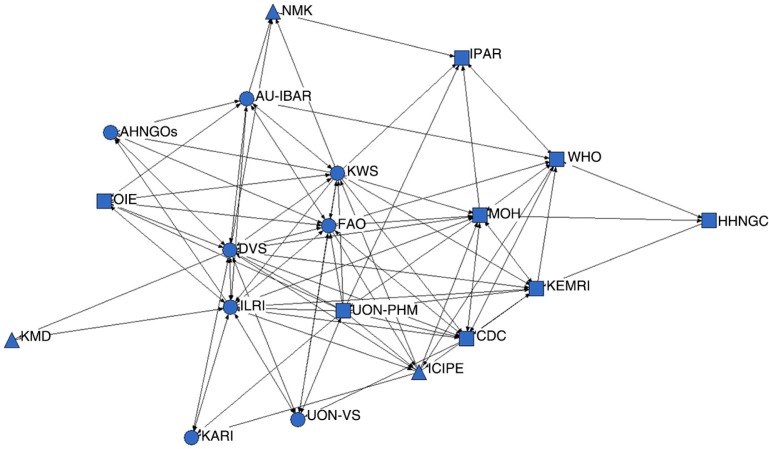

National-level sociogram (Fig. 5) shows how the national, regional, and international stakeholders based in Nairobi are related.

Fig. 5.

Sociograph of the national-level actors: square (public health), circle (animal health), and upward triangle (others). AHNGOs, Animal Health Non Governmental Organisations; AU-IBAR, African Union Inter Bureau of Animal Resources; CDC, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; DVS, Department of Veterinary Services; FAO, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations; HHNGO, Human Health Non Governmental Organisations; ICIPE, International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology; ILRI, International Livestock Research Institute; IPAR, Institute of Primate Research; KARI, Kenya Agriculture Research Institute (renamed Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation); KEMRI, Kenya Medical Research Institute; KMD, Kenya Meteorological Department; KWS, Kenya Wildlife Service; MOH, Ministries in charge of Health; NMK, National Museums of Kenya; OIE, World Organisation for Animal Health; UON-VS, University of Nairobi-Veterinary Services; UON-PHM, University of Nairobi – Public Health; WHO, World Health Organization.

Computed overall binary network density was 0.35 showing that only 35% of the possible relationships existed. The overall clustering coefficient was estimated at 0.56 showing fairly dense local neighbourhoods. Seven stakeholder organisations or groups – CDC, FAO, AU-IBAR, OIE, universities, NGOs, and International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) – had cluster coefficients that ranged from 0.51 to 0.95 (Table 2). This means that they had achieved more than 50% of possible ties in the neighbourhood, attributed to their networks and mandates in OH as well as their resources endowments from donors.

Table 2.

National OH actor–network centrality measures

| Degree | Farness | Closeness | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acronym | Actor | Cluster coefficient | In | Out | In | Out | In | Out | Between-ness | nBetween-ness |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organisations | 0.95 (10a) | 15 | 13 | 42 | 59 | 44 | 33 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| OIE | World Organisation for Animal Health | 0.7 (15) | 25 | 32 | 39 | 48 | 46 | 38 | 2 | 0.6 |

| AU-IBAR | African Union Interafrican Bureau of Animal Resources | 0.66 (28) | 29 | 37 | 38 | 46 | 47 | 39 | 6 | 2 |

| UON-VS | University of Nairobi-Veterinary Services | 0.63 (15) | 25 | 23 | 34 | 50 | 53 | 36 | 7 | 2 |

| NMK | National Museums of Kenya | 0.58 (6) | 14 | 8 | 34 | 81 | 53 | 22 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organisation | 0.56 (55) | 42 | 47 | 32 | 42 | 56 | 38 | 18 | 6 |

| ICIPE | International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology | 0.52 (28) | 24 | 19 | 32 | 47 | 56 | 38 | 18 | 6 |

| ICIPE | International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology | 0.52 (28) | 24 | 19 | 32 | 47 | 56 | 38 | 18 | 6 |

| CDC | Centres of Diseases Control – Kenya | 0.51 (36) | 38 | 42 | 29 | 46 | 62 | 39 | 24 | 8 |

| KWS | Kenya Wildlife Service | 0.47 (78) | 28 | 36 | 37 | 41 | 49 | 44 | 10.5 | 3 |

| ILRI | International Livestock Research Institute | 0.46 (66) | 36 | 41 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 40 | 37 | 20 |

| KEMRI | Kenya Medical Research Institute | 0.44 (36) | 34 | 34 | 31 | 47 | 58 | 38 | 17 | 5 |

| MOH | Ministries in charge of Health | 0.41 (45) | 42 | 47 | 30 | 46 | 60 | 39 | 27 | 9 |

| UON-PHM | University of Nairobi – Public Health | 0.4 (10) | 24 | 21 | 41 | 55 | 44 | 33 | 3 | 1 |

| DVS | Department of Veterinary Services | 0.37 (78) | 53 | 52 | 27 | 40 | 67 | 45 | 61 | 20 |

| WHO | World Health Organisation | 0.32 (36) | 38 | 32 | 30 | 51 | 60 | 35 | 44 | 14 |

| IPR | Institute of Primate Research | 0.25 (10) | 23 | 15 | 36 | 65 | 50 | 28 | 20 | 6 |

| KARI | Kenya Agriculture Research Institute | – | 15 | 15 | 38 | 55 | 47 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| KMD | Kenya Meteorological Department | – | 4 | 4 | 342 | 44 | 5 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean number in brackets refer to standard deviation (n=19) | 28 (12) | 28 (14) | 51 (69) | 51 (9) | 51 (13) | 37 (6) | 16 (17) | −5 | ||

Number in brackets refers to the number of pairs.

The DVS had the highest out and in ties followed closely by MOH, FAO, CDC, ILRI, and AU-IBAR, while NGOs (whose activities are mostly community-based) were one of those with least ties. The sum of geodesic distances from the other actors (in farness) within the network had less variability except for KMD. The values of actor between-ness of DVS, WHO, ILRI, MOH, and CDC imply that more actors depended on them to make connections with others placing them in a powerful position.

Discussions and conclusions

We sought to better understand the formal and informal institutional and organisational arrangements associated with OH institutionalisation processes to provide information to guide and strengthen processes at country level. OH was conceptualised as policy or innovation where stakeholders (who needed to cooperate to resolve a cross-sectoral problem) with diverse roles and networks were a central component. The stakeholders and their networks would require undertaking activities towards mobilisation, alliance building, social acceptance, and institutionalisation of OH. The study applied SNA methods namely snowballing, sociograms and statistical measurements of relationships to generate information on the OH stakeholders in Kenya, their cross-sectoral relationships and the extent to which they had institutionalised OH. To focus the analysis, a specific cross-sectoral health problem, RVF, was identified. The SNA snowball method facilitated mapping of 32 and 21 public and private RVF and OH stakeholders at national and subnational levels, respectively, drawn from animal and public health sectors and climate prediction agencies. Each stakeholder played a unique role and therefore we considered all as critical for cross-sectoral collaboration. Identification of climate prediction agencies at national level and a cross-sectoral steering group (DSG) of the ALRMP at subnational show that cross-sectoral collaborations for zoonotic diseases may go beyond the two health sectors.

Sociogram for the subnational stakeholders revealed a denser network among the public health stakeholders, which was attributed to more stakeholders and existence of within-sector multilevel coordination platforms. Network density measures showed that a significant number of relationships were missing at both levels but more at subnational level. These together with the limited efforts to institutionalise OH at subnational despite policy support can be attributed to failure to establish cooperation platforms among livestock sector stakeholders and between them, the community and public health sectors. Considering this happens at a level close to communities and where RVF outbreaks or other zoonotic events occur, then, concerted OH actions focused on solving a problem at animal level would be challenging.

Despite missing ties at national level, collaborating stakeholders – led by line ministries with support from development and technical partners – had mobilised for and institutionalised OH through formal structures. Examination of the institutionalisation process led a conclusion that the mobilisation for OH had evolved from informal to formal cross-sectoral (OH) mixed (top-down and home grown) collaborations, driven by three zoonotic diseases, regional networks, and global technical and donor agencies. It had mostly been based on arguments and lessons learnt on cross-sectoral projects and issues. This is attributed to the fact that only a few studies (32–34) explicitly demonstrate economic benefits of OH. Yet, in evidence-based innovations, mobilisation to institutionalisation activities is designed to link stakeholders with scientific evidence and technologies amongst other things (26).

The missing ties were attributed to the ‘on invitation’ alliance building where about 47% of identified stakeholders are out of OH coordination. While missing relationships may reflect possibility of missed resource flows from nearly half of the un-invited stakeholders, it goes to show that the OH network can progress to institutionalisation as long as key stakeholders are looped in. However, the impacts of missed opportunity to bring all (and their resources) on board might be evident when major disease events occur.

Applying SNA proved useful in understanding the power and influence of different stakeholders. For example, ALRMP (and its DSG and HSG) emerged as a stakeholder who connected most subnational stakeholders and whom also many stakeholders sought to influence. This implies that platforms with cross-sectoral mandate and coordination are critical in OH networks. The centrality measures findings show that cross-sectoral mandate and coordination is critical in networks. At both levels, high ties (in and out) of the MOH and DVS can be attributed to their legal mandate to implement prevention and control of diseases, which made other stakeholders want to exert their influence on them. On the other hand, high ties of CDC, WHO, and FAO reflect their global mandates in OH and their networks. These five organisations (CDC, WHO, FAO, MOH, and DVS) can be said to enjoy an advantage of having alternative ways to access resources and are able to call on more resources if needed, evidenced by them rallying others around ZTWG and ZDU. The presence of regional and international communities seem to have offered an opportunity for the top-down OH mobilisation as well as the link between local OH initiatives with global OH and regional platforms/networks. Through support from these organisations, the country had made direct and indirect links with major global and regional networks.

While this analysis was limited to national and subnational level, many regional-level networks linked to national and international stakeholders were identified. There may be the need for a cross-network regional platform to rationalise and coordinate the various networks and initiatives, which are likely duplicating roles and memberships, and thus efforts.

In conclusion, the need to institutionalise OH at subnational level is emphasised particularly in order to address the low networking between animal and public health sector who are considered as the critical drivers of OH. Also, the national OH can be strengthened to pull more resources. To do so, this study recommends the following:

Shortening of the OH institutionalisation process at subnational by creating formal OH platforms (OH units) that build on existing cross-sectoral coordination platforms, mainly the HSG, to exploit the MOH's higher influence in the network.

Increasing the capacity of the animal health sector to participate in the OH network by supporting DVOs’ to network livestock clusters. This could be achieved by creating community and district livestock committees, and stakeholder forums. Similar to human health NGOs, animal health NGOs could be encouraged to support DVOs to coordinate forums.

Extending membership of the Zoonotic Technical Working Group (ZWTG) to incorporate remaining stakeholders and other experts such as wildlife ecologists, zoologists, communication for development experts, sociologists, and health economists.

This study also recommends that FAO, OIE, and WHO exploit their OH tripartite arrangements to strengthen OH regional coordination. The activities of the regional OH platform would then finally be linked to national OH platforms which in turn would be linked to subnational networks.

Further, we note that the data collection and analysis methodologies used had limitations. First, the strength of relationships, though based on frequency and intensity of relationships, were subjective and could have introduced respondent bias. Secondly, the approach to convert ordinal to interval data could have also introduced author bias. Thirdly, inherent to SNA methods, binarising the relationship strength data leads to inform loss. Fourth, the data were collected in a cross-sectional survey. It would have been good to show interval sociograms. However, SNA proved useful in mapping the stakeholders, visualising the network, and generating mathematical properties of the network, which may not have been archived by other approaches of stakeholder mapping. Lastly, the information generated provides a baseline for future analysis of the impacts of the OH institutionalisation in the country and generation of temporal sociograms.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Canada through the Agriculture and Research Platform hosted at the International Food and Policy Research Institute. The authors acknowledge all field staff, key informants, and livestock keepers who freely provided information and collaborating institutions namely CDC-KEMRI. Also acknowledged are Bernard Bett of ILRI and Bouna Diop of FAO.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.King LJ. Emerging and re-emerging zoonotic diseases: challenges and opportunities. Compendium of technical items presented to the International Committee and to Regional Commissions. World Organization for Animal Health (OIE); Technical paper presented at the 72nd General session; 23–28 May, 2004; Paris. [Google Scholar]

- 2.OIE. One World One Health. Bulletin. Available from: http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Publications_%26_Documentation/docs/pdf/bulletin/Bull_2009-2-ENG.pdf [cited 14 July 2012]

- 3.Taylor HL, Latham SM, Woolhouse MEJ. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:983–9. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolhouse MEJ, Gowtage-Sequeria S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1842–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050997. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1112.050997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franz DR, Jahrling PB, Friedlander AM, McClain DJ, Hoover DL, Bryne WR, et al. Clinical recognition and management of patients exposed to biological warfare agents. JAMA. 1997;278:399–411. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Columbus C. Mad cow and other maladies: update on emerging infectious diseases. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2004;17:411–17. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2004.11928005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centre for Food Security and Public Health. Factsheets. 2009. Available from: http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets [cited 27 February 2016]

- 8.Hughes JM, Wilson ME, Luby SP, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ. Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1743–8. doi: 10.1086/647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Media centre. 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs354/en/ [cited 27 February 2016]

- 10.Newman AP, Reisdorf E, Beinemann J, Uyeki TM, Balish A, Shu B, et al. Human case of swine influenza A (H1N1) triple reassortant virus infection, Wisconsin. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1470–2. doi: 10.3201/eid1409.080305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/mers-cov/en/ [cited 27 February 2016]

- 12.Peters CJ, Peters JW. An introduction to ebola: the virus and the disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Supplement 1):ix–xvi. doi: 10.1086/514322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fournié G, Guitian J, Desvaux S, Cuong VC, Dung DH, Pfeiffer DU, et al. Interventions for avian influenza A (H5N1) risk management in live bird market networks . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(22):9177–9182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220815110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace RG, Kock RA. Whose food footprint? Capitalism, agriculture and the environment. Hum Geogr. 2012;5:63–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kock R. Drivers of disease emergence and spread: is wildlife to blame? Onderstepoort J Vet Res Art. 2014;81:4. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v81i2.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwabe CW. Veterinary medicine and human health. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. p. 713. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wildlife Conservation Society. Conference summary report. New York: The Rockefeller University; 2004. Sep 29, One World, One Health: building interdisciplinary bridges to health in a globalized world. Available from: http://www.oneworldonehealth [cited 1 May 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Food and Agriculture Organization, World Organization for Animal Health, World Health Organization, United Nations System Influenza Coordinator, United Nations Children's Fund, World Bank. Contributing to One World, One Health: a strategic framework for reducing risks of infectious diseases at the animal–human–ecosystems interface. Available from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/aj137e/aj137e00.HTML [cited 3 June 2013]

- 19.Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Waltner-Toews D, Whittaker M, Tanner M. One Health: the theory and practice of integrated health approaches. CABI. 2015 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781780643410.0000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.FAO, OIE, WHO. The FAO–OIE–WHO collaboration: sharing responsibilities and coordinating global activities to address health risks at the animal–human–ecosystems interfaces. 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/tripartite_concept_note_hanoi_042011_en.pdf [cited 4 May 2013]

- 21.WHO. A report of Joint WHO/DFID meeting with the participation of FAO and OIE. Geneva: WHO; 2005. The control of neglected zoonotic diseases – a route to poverty alleviation. [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO, FAO, OIE. Report of the WHO/FAO/OIE joint consultation on emerging zoonotic diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Bank. People, pathogens, and our planet. Volume 1: towards a One Health approach for controlling zoonotic diseases. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC. Rift valley fever: scientific pathways towards public health prevention and response. 2008. Unpublished workshop report. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson G, Frances J, Levacic R, Mitchell J, editors. The coordination of social life. London: Sage publications; 1991. Markets, Hierarchies and networks. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young D, Borland R, Coghill K. An actor-network theory analysis of policy innovation for smoke-free places: understanding change in complex systems. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1208–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latour B. Pandora's Hope Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanneman RA, Riddle M. Introduction to social network methods. Chapter 1: social network data. Riverside, CA: Department of Sociology at the University of California; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everett SP, Freema MG, Borgatti LC. UCINET for Windows: software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anyamba A, Linthicum KJ, Small J, Britch SC, Pak E, de La Rocque S, et al. Prediction, assessment of the Rift Valley fever activity in East and Southern Africa 2006–2008 and possible vector control strategies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2 Suppl):43–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schelling E, Wyss K, Bechir M, Daugala D, Zinsstag J. Synergy between public health human and veterinary services to deliver human and animal health. Br Med J. 2005;331:1264–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roth F, Zinsstag J, Orkhon D, Chimed-Ochir G, Hutton G, Cosivi O, et al. Human health benefits from livestock vaccination for brucellosis: case study. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:867–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Bank. People, pathogens and our planet: the economics of One Health. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2012. [Google Scholar]