Abstract

Performance-Based Financing (PBF) is a promising approach to improve health system performance in developing countries, but there are concerns that it may inadequately address inequalities in access to care. Incentives for reaching the poor may prove beneficial, but evidence remains limited. We evaluated a system of targeting the poorest of society (‘indigents’) in a PBF programme in Cameroon, examining (under)coverage, leakage and perceived positive and negative effects. We conducted a documentation review, 59 key informant interviews and 33 focus group discussions with community members (poor and vulnerable people—registered as indigents and those not registered as such). We found that community health workers were able to identify very poor and vulnerable people with a minimal chance of leakage to non-poor people. Nevertheless, the targeting system only reached a tiny proportion (≤1%) of the catchment population, and other poor and vulnerable people were missed. Low a priori set objectives and implementation problems—including a focus on easily identifiable groups (elderly, orphans), unclarity about pre-defined criteria, lack of transport for identification and insufficient motivation of community health workers—are likely to explain the low coverage. Registered indigents perceived improvements in access, quality and promptness of care, and improvements in economic status and less financial worries. However, lack of transport and insufficient knowledge about the targeting benefits, remained barriers for health care use. Negative effects of the system as experienced by indigents included negative reactions (e.g. jealousy) of community members. In conclusion, a system of targeting the poorest of society in PBF programmes may help reduce inequalities in health care use, but only when design and implementation problems leading to substantial under-coverage are addressed. Furthermore, remaining barriers to health care use (e.g. transport) and negative reactions of other community members towards indigents deserve attention.

Keywords: Accessibility, health services, inequalities, poverty, Sub-Saharan Africa, user-fees

Key messages

A system of targeting the poorest of society in PBF programs may help reduce inequalities in health care use as improvements in access, quality and promptness of care for the poorest of society were perceived.

Community health workers were able to identify very poor and vulnerable people with a minimal chance of leakage to non-poor people.

There was substantial under coverage which can, in part, be explained by design and implementation problems associated with targeting procedures.

Removal of user-fees for the poorest of society did not discard all (financial) barriers to health care use and those targeted by the system perceived negative reactions by other community members.

Introduction

In 2015, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) reached their target date. Although progress in reaching the goals has been made (United Nations 2013), there are indications that it was inequitable (Boerma et al. 2008; Victora et al. 2012). The poor profit much less from the MDGs than their richer counterparts, especially in the area of maternal and child care (Boerma et al., 2008). Facility-based health services, such as skilled birth attendance, were most inequitable, whereas community-level interventions were more equitable (Barros et al. 2012).

The mechanisms that underlie socio-economic inequities in maternal and child health care are complex, and various social, economic, cultural and political determinants play a role (CSDH 2008). Low health system performance is one of the factors that underlies these inequities in developing countries. The costs of care, the low quality of services, if provided at all, and lack of respectfulness of health care providers towards poor and otherwise vulnerable patients, are important barriers to seeking health care among the poorest of society (HSKN 2007; Bakeera et al. 2009).

A promising approach to address low health system performance is Performance-Based Financing (PBF) (Witter et al. 2012). PBF targets health facilities using a ‘fee-for-service-conditional-on-quality’ approach (Fritsche et al. 2014). PBF has been found to be effective in improving health care quality, health care utilization and health outcomes (Basinga et al. 2011; Witter et al. 2012). However, there are concerns that socio-economic inequalities are not adequately addressed and that a focus on easy-to-reach population groups, rather than poor and vulnerable people, may exacerbate inequalities (Witter and Adjei 2007). A targeting system within PBF, with incentives for reaching the poor, may help increase health care utilization among the poorest and most vulnerable of society. However the workings of targeting within PBF have not yet been properly described and evaluated. There are indications that targeting can be costly, bureaucratic, and can lead to leakage to richer or more influential groups, and to under-coverage of the target population (CSDH 2008).

Of further concern is the notion that implementing new guidelines or procedures in routine health care practice, such as a targeting system, is not easy (Davies and Tailor-Vaisey 1997; Grol and Grimshaw 2003; Grol et al. 2007), let alone in resource poor settings. Grol and Grimshaw (2003) and Grol et al. (2007) note three categories of barriers that can hamper the implementation of health care guidelines: organizational barriers, social barriers and professional/individual barriers. Organizational barriers can include financial disincentives, organizational constraints and resource constraints. Social barriers can include lack of support from management, standards of practice and social norms. Professional/individual barriers can include negative attitudes and lack of knowledge. Conversely, a better compliance to a guideline is associated with acuteness of the health problem, the quality of the evidence, compatibility of the guideline with existing values, the complexity of decision-making, concrete descriptions of the desired performance and limited necessity of new skills and organizational change (Grol and Grimshaw 2003).

Cameroon’s progress towards meeting the MDGs has been slow, especially for child and maternal health (United Nations 2012), with inequalities in reaching these goals between the poorer North and particularly rural areas, and the richer centre provinces [Institut National de la Statistique (INS) and ICF International, 2012]. In 2012, a PBF programme with specific incentives for reaching the poorest of society was implemented in 14 health facilities in the North. In the programme, extremely poor and vulnerable poor are registered as ‘indigents’ (from here on referred to as ‘indigents’; other poor and vulnerable people not registered in the programme will be referred to as ‘non-indigents’).

The aim of this study was to evaluate a system of targeting the poorest of society in Northern Cameroon. Specifically, we aimed to describe the targeting criteria and procedures as defined in programme documents and as implemented in practice and assess the implications of these criteria and procedures in terms of (under) coverage, leakage and perceived positive and negative effects.

Methodology

Study setting

The study took place in Northern Cameroon, in the PBF pilot programme of the Diocese of Maroua. The area is characterized by extreme poverty (INS and ICF International 2012). The programme includes 14 health facilities (13 located in rural zones) run by the Catholic mission, which have performance contracts with payment on the basis of performance targets (e.g. consultations and deliveries). The PBF programme uses a ‘fee-for-service-conditional-on-quality’ payment scheme (Fritsche et al. 2014). Services are linked to primary, secondary and community level indicators (see Supplementary Materials S3–S5). The PBF payments for indigents exempt indigents from user-fees. For other patients, user-fees apply (Ziebe and Vaggai 2013). The facilities provide quarterly overviews of indigents treated to the payment agency, after which they are remunerated. Subsidies can double depending on quality of care, which is evaluated quarterly through community surveys and audits (CDD 2013). If revenues from PBF are larger than actual costs, performance bonuses are available for health personnel and community health workers known in the programme as “COSA members”.

Study sample

We included 7 out of 14 facilities in our study: two facilities were purposively selected (the only participating hospital and urban facility); the remaining 12 rural facilities were stratified into three socio-economic regions: very poor, poor and less poor (Table 1) (Yonga and A 1995). To ensure there would be enough indigent participants in our sample and saturation would be reached, we randomly selected three facilities from group one (where more indigents live) and two facilities from groups two and three, by drawing notes from an envelope.

Table 1.

. Selected facilities and their characteristics

| Name of facility | Poverty profile (Very poor/poor/moderately poor) | Selected for the study (Yes/No) | Catchment population | Number of staff members | Number of COSA membersa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre de santé de Douvangar | Very poor | Yes | 13108 | 5 | 30 |

| Centre de santé de Djinglya | Very poor | No | |||

| Centre de santé de Goudjoumdélé | Very poor | Yes | 9292 | 5 | 20 |

| Centre de santé de Magoumaz | Very poor | No | |||

| Centre de santé de Mayo Ouldémé | Very poor | Yes | 32623 | 9 | 42 |

| Hopital de Tokombéré (hospital) | Very poor | Yes | 16952 | 62 | 40 |

| Centre de santé de Guétchéwé | Poor | No | |||

| Centre de santé de Ouro-Tada | Poor | Yes | 19635 | 9 | 68 |

| Centre de santé de Zamay | Poor | No (Pilot facility) | |||

| Centre de santé de Zélévet | Poor | No | |||

| Centre de santé de Domayo (urban) | Less poor | Yes | 14825 | 23 | 6 |

| Centre de santé de Guili | Less poor | Yes | 17090 | 5 | 24 |

| Centre de santé de Kila | Less poor | No | |||

| Centre de Santé de Sir | Less poor | No |

aCOSA members are community health workers.

Documentation review

All PBF project documentation was requested from the project coordinator and reviewed. During field visits, facility-level documentation (e.g. indigent registers) was collected. Documentation on the targeting procedures was scarce. The following documents were available and were reviewed: project proposal (CDD 2011), baseline study (CDD 2012a), activity execution guide (CDD 2013), procedure manual (CDD 2012b), indigent lists, consultation registers, workshop report (CDD 2012c) and business plans of the health facilities.

Interviews with key informants

Key informants were purposively selected on the basis of their role in the PBF programme. We included a variety of respondents, from health care personnel to COSA members. A total of 59 interviews were conducted (Table 2).

Table 2.

. Overview of the interviewed key informants

| Respondent type | Number of interviews |

|---|---|

| COSA membera | 26 |

| COSA president | 6 |

| Health facility personnel | 21 |

| Health facility director | 3 |

| PBF coordinator | 2 |

| Health coordinator | 1 |

| Total | 59 |

aCOSA members are community health workers.

Focus group discussions

Participants

Several groups of community members were invited to the focus group discussions (FGDs): (a) indigents who had attended the facility in 2013; (b) indigents who had not attended the facility in 2013; and (c) otherwise poor and vulnerable people not registered as indigent (‘non-indigents’) who had attended the facility in 2013. Separate male and female focus groups were organized. The facilities provided a list of all indigents and their characteristics (age, gender, facility attendance) registered in the catchment area in 2013. Local researchers split the list into four new lists by gender (male/female) and facility attendance (yes/no). Next, the lists were rearranged in alphabetical order and 15 people were randomly selected and invited for an FGD. If the selected indigent was a child, the main caretaker was invited. Non-indigents were identified by health care personnel (people that had difficulties paying health care costs in the past year) and were also invited.

In total, 33 FGDs with 238 participants (5–11 participants per group) were conducted (see Table 4). We were unable to organize six FGDs with indigents who had not attended the facility and three FGDs with non-indigents because participants were too weak to come to the FGD or had passed away. Indigent and non-indigent participants had similar socio-demographic characteristics (Table 3). Indigents who did not visit the facility were more often above the age of 60.

Table 4.

. Differences between community perceptions of poverty and vulnerability, targeting criteria applied in practice and predefined targeting criteria

| All groups and characteristics | Community | In practice | Predefined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of importance | |||

| Elderly | ++ | ++ | |

| Orphans | ++ | ++ | x |

| Widows | ++ | ++ | x |

| Blind | + | ++ | x |

| Handicapped | + | ++ | x |

| Leprosy patients | + | + | x |

| Mentally ill | + | + | x |

| Chronically ill | + | + | x |

| No family or support | ++ | ++ | x |

| Inability to work | ++ | ++ | |

| Food insecurity | ++ | ++ | |

| Lack of strength | ++ | ++ | |

| Dependency | ++ | ++ | |

| Lack of financial resources | + | ++ | x |

| Doesn’t own land or cattle | + | + | |

| Has nothing | + | ++ | |

| No or dirty clothing | + | ++ | |

| No housing or in bad state | + | + | |

| Cannot pay school fees | + | + | |

| Large families | + | + | |

++, highly frequent, highly extensive; + , little frequent, little extensive;

frequency, the number of respondents that mention the theme; extensiveness, the extensiveness of the theme across different sources;

x, Criteria predefined in programme documents.

Table 3.

. Characteristics of the Focus Groups and participants

| Indigents that attended the facility in 2013 (n = 88) | Indigents that didn’t attend the facility in 2013 (n = 20) | Non-indigents that attended the facility in 2013 (n = 80) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of female FGDs | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| Number of male FGDs | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| Age mean (SD) | 48.4 (18.6) | 66.2 (17.7) | 46.4 (16.8) |

| >60 years | 25.0% | 65.0% | 17.5% |

| Proportion females | 55.7% | 55.0% | 50.0% |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 15.9% | 20.0% | 10.0% |

| Married | 39.8% | 25.0% | 38.8% |

| Separated | 10.2% | 55.0% | 15.0% |

| Widow | 23.9% | 17.5% | |

| Widower | 3.4% | 1.3% | |

| Unknown | 6.8% | 17.8% | |

| Main occupation | |||

| Housewife | 45.5% | 30.0% | 45.0% |

| Farmer | 30.6% | 45.0% | 32.5% |

| Student | 2.3% | 3.8% | |

| Guard | 1.1% | ||

| Constructor | 1.3% | ||

| Retired | 2.3% | ||

| Unemployed | 14.8% | 15.0% | 11.3% |

| Informal jobs | 1.3% | ||

| Unknown | 3.4% | 10.0% | 5.2% |

| Difficulty in meeting food needs the past month | 88.0% | 88.9% | 92.5% |

| Indigent criteria meta | 89.8% | 100% | 27.5% |

aAccording to the predefined list of criteria.

Procedures

Two local researchers, one senior (R.Z.) and one assistant (D.V.), were extensively trained in qualitative research techniques and pilot-tested the tools in Zamay, a facility that had not been selected for the study. Some minor changes were made hereafter, particularly in terms of language use (e.g. some uncommon terms like stigmatization were explained).

The local research team conducted the FGDs and interviews between September 2013 and April 2014, in chaplaincies, churches or in laboratories and conference rooms at the health facilities. The interviews lasted between 23 and 87 min and were conducted in French. The FGDs lasted between 22 and 113 min and were conducted in French or one of the local languages (Fulfudé, Bana, Molfolé, Moufou, Mafa, Maktal, Mada, Ouldémé). All interviews and FGDs were recorded. Interviews were transcribed verbatim. As many of the local languages are only spoken, the FGD recordings were translated and transcribed into French.

Instruments

Guides were used for the interviews and FGDs (Supplementary Materials S1 and S2) and included general and probing questions focusing on defining different socio-economic groups in society, targeting procedures and positive and negative effects of targeting on access to care, quality of care, stigmatization or other non-specified effects. Indigent participants were asked additional questions on their perceptions of social labeling, while indigent participants who had not attended the facility were asked additional questions on reasons for non-attendance. A short demographic questionnaire was administered after the interviews and FGDs.

Analysis

The analysis was based on the framework method (Pope and Mays 2000). After transcribing the recorded interview/FGD, the researchers familiarized themselves with the transcriptions. Hereafter, a set of 10 interviews and FGDs from three different facilities were coded in NVivo by the primary researcher (I.F.). This led to the development of generic analysis frameworks for the interviews and FGDs (Pope and Mays 2000; Gale et al. 2013). Next, three researchers (I.F., R.Z. and D.V.) applied the generic analysis frameworks to a representative set of five interviews and FGDs using NVivo. The purpose of this step was to evaluate the frameworks and cross-check the identified themes and codes. The researchers discussed their findings and the analysis frameworks were updated. Hereafter, the primary researcher (I.F.) systematically coded the remaining interviews and FGDs using the new analysis frameworks. Emerging codes were added and some codes were merged. Finally, NVivo was used to create so-called ‘tree maps’ to discover patterns in the data by determining frequency (how many times a code was mentioned) and extensiveness (how many participants/sources mentioned a code). To gain a deeper understanding of the issue under study, data from different sources were triangulated and references to illustrative quotations were selected.

Results

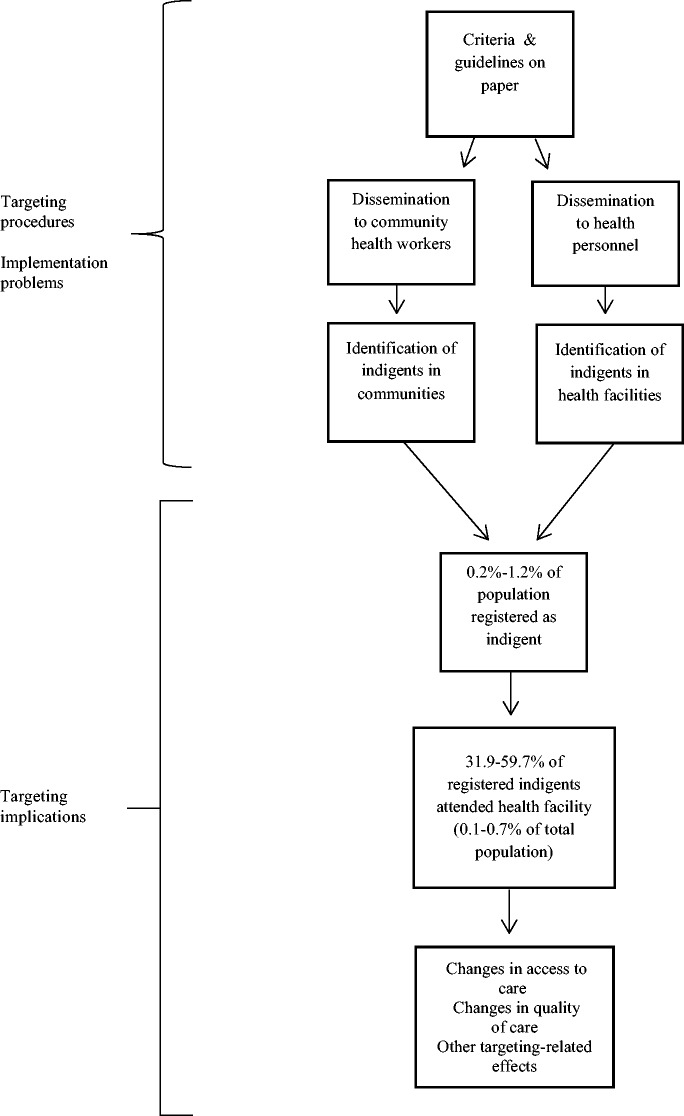

Figure 1 depicts the various steps undertaken to target the indigents in the PBF programme in Cameroon and the implications of the system. Each step will be described using the results of the documentation review, the Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and the FGDs with indigents and non-indigents.

Figure 1.

. Flowchart of the steps undertaken to target indigents in the PBF programme and its implications.

Targeting procedures

Criteria and guidelines predefined in programme documents

At the start of the programme, 10 criteria for identifying indigents were established during a workshop with PBF, health facility staff and community stakeholders (CDD 2012c) (see Table 4).

COSA members were held responsible for the identification of indigents and received 50 000 FCFA (around €76) yearly as compensation (CDD 2013). COSA are linked to the facility catchment area and its members are elected community representatives (e.g. members of the parish). Facility catchment areas consist of several villages and each village has at least one COSA member.

A priori objectives for the number of indigents to be identified were set yearly. These were based on facility registries of people who were unable to pay for health care in the previous year and served as an indication. At the time of this study (2013), the objective was to register a total of 1272 indigents in a catchment population of 191 544 (0.7%). Quarterly objectives, serving as minimum, were also set by health facilities in business plans together with COSA members. Expected numbers of indigents in business plans varied per quarter due to the seasonal patterning of health care utilization.

Dissemination of criteria and guidelines to community health committees and health personnel

According to the guidelines (CDD 2011), dissemination of criteria and targets to COSA members should be done by the COSA president. In practice, most COSA members received the criteria from the COSA president and/or the health facility. A few COSA members mentioned that they never received any fixed criteria and that they established their own criteria ‘Facilitator: have the targeting criteria been pre-established? “No, we observe and we know the community” (COSA member, Douvangar)’. The objectives for the number of indigents to be identified were not clear. A few COSA members mentioned that they received a quota: ‘We bring the number that they ask us to bring. If we bring more people the resources might run dry(COSA member, Domayo)’. ‘The project fixes the number of indigents brought by each COSA member. It would be better if this is left open so that the maximum is done (COSA member, Domayo)’ while others said there were ‘no objectives’.

Identification of indigents in the community and health facility

In practice, mostly the COSA members and sometimes health personnel identified indigents. In a few cases previously established lists (i.e. established by churches) of indigents were already available. COSA members identified indigents taking into account the pre-defined criteria and several economic characteristics (Table 4). Hence, the criteria applied in practice were broader than the pre-defined criteria. COSA members mentioned that they used various methods to identify indigents. The most frequently mentioned were: consulting other community members ‘The first thing we do is contact the village chiefs and ask them if there are people who suffer…’(COSA member, Goudjoumdélé), using own knowledge of the community ‘We know our community, even before this project, we knew the people with problems’(COSA president) and household observations. Household observations mainly consisted of an informal chat with the ‘potential’ indigents, checking their personal state (hygiene, appearance) and the state of their housing. Less often mentioned were surveys or formal meetings with community members or COSA members. Most COSA members mentioned that they received a ‘little bonus’ at the end of the trimester. Some mentioned getting paid per indigent referred while others said that they did not get paid at all ‘Our work is voluntary, we do not receive any financial compensation’(COSA member, Domayo).

Health personnel also mentioned various ways of identifying indigents at the facility level. Most mentioned that they had a list with names of indigents, submitted yearly by the COSA and/or that COSA members wrote out a note for the indigents mentioning their status. Health personnel usually first looked at the list ‘When the indigents are sick they come to our health facility, if we have the list we take care of them immediately’(Health personnel, Douvangar) and the referral notes ‘I see a lot of indigents that have a little note in their hands which helps us to recognize them as indigents’(Health personnel, Domayo). Some health personnel mentioned that they further checked the patient’s financial status by posing them or their companion questions ‘These patients are often accompanied by others that confirm that the person suffers and that there is nobody to take care of them and when you ask them questions you equally recognize that the person has no one and you have no other choice’(Health personnel, Domayo).

Identification of new indigents happened quite often at all facilities. According to the key informants, these were patients that came from outside the catchment area and did not appear on the COSA lists (e.g. Nigerian immigrants attending the Douvangar facility) or other groups that were difficult to identify, like street children (Domayo). At the hospital, many of the indigents came from outside the catchment area and were not on the COSA list ‘If there are people coming from outside the catchment area that don’t have financial means it’s the hospital that puts their name on the indigent list’(COSA president). To check whether these patients fulfilled the criteria, health personnel mentioned they used different methods: observations, posing questions, presenting the bill to check whether it can be paid, or going back to the villages to check if the patients were really indigents.

Implementation problems

Several problems with the implementation of the targeting system within the PBF programme were identified. In line with the review by Grol and Grimshaw (2003), the problems could be categorized into three levels: organizational, social and professional/individual.

Organizational

Financial incentives were considered too low and not in balance with the increase in workload ‘Some COSA members have gotten angry because they are not remunerated despite the fact that they have referred and accompanied indigents to the facility.’(COSA president). There was also a lack of transport to identify more indigents, particularly in mountainous areas, and to bring them to the facility ‘It’s not easy to do your identification by foot. A bike would make things a lot better’(COSA member, Tokombéré hospital). FGDs further showed that in only a few cases indigents were actually accompanied to the facilities by COSA members. Finally, there were no clear procedures as to how to inform the indigents about the benefits of the system. As a result many indigents were not informed at all ‘I wasn’t informed. Another blind person got back from the facility yesterday night and told me that the center invites poor people to come’(Male indigent, Mayo-Ouldémé).

Social

There was dispute among health personnel and COSA members about the distribution of performance bonuses and there were doubts about the fairness of the payment system. ‘The financing system needs to be clear and concrete. It shouldn’t only be communicated verbally. Now they promise us things but we never receive anything’(COSA member, Goudjoumdélé). ‘There are problems at the level of the bonuses. They say that the bonuses will be distributed equally among health personnel but in reality this is not the case’(Health personnel, Guili). There were also worries, particularly among health personnel, about the future of the targeting system and if and how it would continue once PBF would end ‘We are worried that the project will end, the people [indigents] will be used to it and all of a sudden there will be no more funds to take care of them’(Health personnel, Douvangar).

Professional/individual

There was a lack of clarity and knowledge about the criteria ‘What do you do when there is a family with many children? Do you consider them all as indigents?’(COSA president, Goudjoumdélé). KIIs further revealed that in practice COSA members often identified the easily recognizable indigents such as the elderly, orphans/otherwise vulnerable children, widows/widowers, the handicapped and the blind. ‘What I see a lot on the list here are the abandoned elderly’(Facility director, Mayo-Ouldémé). ‘COSA members are mostly interested in the elderly and poor children. There is not a good system to identify other indigents.’(Health personnel, Domayo). COSA members had more difficulty identifying those indigents whose illnesses were not visible, such as HIV/AIDS patients.

Additionally, COSA members and health personnel found the current criteria too strict and some groups were left out ‘We need to expand the criteria to the poor because in August [the wet season] we see that almost everyone could be considered an indigent, they cannot pay the health care costs, their granaries are empty and they are famished’(Health personnel, Mayo-Ouldémé). At the same time, many COSA members were unmotivated to identify more indigents ‘They don’t recognize our efforts even though we help the facility a lot’(COSA member, Douvangar).

Targeting implications

Under-coverage and leakage

There were no indications that leakage was an important concern within the targeting system. Only a minority of the health personnel experienced that some ‘indigents had money on them when presented with the bill’. In turn, criteria applied in practice were similar to the community perceptions of poverty and vulnerability (Table 4). Socio-economic data further confirmed that indigents were indeed poor and socially vulnerable (Table 3).

Conversely, under-coverage was a concern. First, identified indigents constituted a tiny proportion of the catchment population (maximum 1.2%; see Table 4) and the indigents that attended the facility constituted an even tinier proportion of the population (maximum 0.7%; see Table 5). Second, non-indigent participants identified themselves as indigents ‘An indigent is like me, I have nothing; my husband passed away, I suffer and have nothing to eat’(Non-indigent participant, Goudjoumdélé) and were found to have similar socio-economic characteristics (Table 3). Third, the focus on only some of the groups that were listed in the predefined criteria (widows, orphans) while focusing less on other groups (e.g. HIV patients) and the poor motivation of COSA members to identify more indigents is likely to have influenced coverage rates.

Table 5.

. Targeting outcomes for the included facilities

| Hôpital de Tokombéré | Douvangar | Mayo- Ouldémé | Goudjoumdélé | Ouro- Tada | Domayo | Guili | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population of catchment area | 16 952 | 13 108 | 32 623 | 9292 | 19 635 | 14 825 | 17 090 |

| Patients that attended the health facility in 2013 | 9019 | 4150 | 5400 | 3037 | 9966 | 24 873 | 3061 |

| % population that attended the health facility in 2013 | 53.2% | 31.7% | 16.6% | 32.7% | 50.8% | 167.8% | 17.9% |

| Number of registered indigents | 207 | 92 | 91 | 116 | 92 | 74 | 67 |

| Registered indigents as % of catchment area population | 1.2% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 1.2% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.4% |

| Number of indigents that attended the health facility in 2013 | N.A.a | 44 | 29 | 67 | 32 | 44 | 40 |

| % registered indigents that attended health facility in 2013 | N.A.a | 47.8% | 31.9% | 57.8% | 34.8% | 59.5% | 59.7% |

| Registered indigents that attended health facility in 2013 as % of catchment area population | N.A.a | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.7% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% |

aConsultation list did not match the list of registered indigents.

Perceived positive and negative effects of the targeting system

Change in access to care

According to most indigents, access to care had improved since the introduction of the targeting system ‘I went to the health center with my brother’s son who had a fracture. I had only 2000FCFA on me but they gave it back and the care, which lasted 3 months, was for free’(Female indigent, Goudjoumdélé). The relatively high percentages of registered indigents that attended the health facilities in 2013 (32–60%; Table 4) support this finding. Nevertheless, these percentages also show that not all identified indigents used care, and our FGDs and KIIs revealed that not all (financial) barriers were discarded by the system. In fact, many similar barriers were identified in the indigent (those that attended the facility and those that did not) and non-indigent groups. One persisting financial barrier mentioned by many indigents was the long distance to the facility and the lack of financial means to pay for transport ‘It’s good to go to the health center when you are sick. But for me, I don’t go because I can’t find any money for the transportation.’(Female indigent, Domayo). Some indigents reported that they preferred to go to a traditional healer because the distance was shorter and the fees were lower. Not having any money to buy food when hospitalized or to swallow prescribed medication was also mentioned as a barrier by some indigent participants.

There were also non-financial barriers that hampered access to care. Most often mentioned was a low perceived severity of the illness ‘For others, when the illness is not that serious they will take some “bil-bil” [local alcoholic beverage] and think it will pass’(Male indigent, Ouro-Tada).

Key Informants additionally mentioned that there were some indigents that ‘refused to accept their status’ and feared stigmatization. Also, indigents expressed worries regarding the quality of care when it was free. Key Informants further revealed some difficulties for indigents in accessing secondary care (hospitals). As only one hospital (only providing free obstetric care) participates in the PBF programme, health personnel at the primary level often mentioned that hospital treatment costs were not covered ‘It was clearly defined within the programmethat in the case of a referral, the person has to pay’(COSA member, Domayo). However, health personnel said that the facility sometimes paid for transport to the hospital or part of the treatment costs ‘Once they arrive at the hospital and say the bill is around 50 000 CFA, we divide that in two and we pay around half’(Health personnel, Goudjoumdélé). Two indigent participants at the Douvangar facility also mentioned that they got ‘10 000 CFA from the health facility’ when they were referred.

Change in quality of care

Both indigent and non-indigent participants identified improvements in quality of care since the introduction of PBF, particularly in the area of hygiene and facilities ‘There are changes: there are new buildings, the toilets are well maintained, and there are no more flies’(Male non-indigent, Mayo-Ouldémé). Some differences between indigent and non-indigent groups were noted. In indigent groups, a few participants mentioned that they were prioritized over other patients, while in non-indigent groups long queues were perceived as an inconvenience. In indigent groups, many participants perceived positive changes in attitudes of health care staff ‘The other nurses used to scold us but these don’t do that and when you arrive they immediately help you’(Female indigent, Mayo-Ouldémé). In non-indigent groups, some participants mentioned lack of respect, impatience and unavailability of staff ‘Often the nurses are not in place. Either they are at home or in a bar’(Female non-indigent, Douvangar).

Other targeting-related effects

Several other positive effects of the targeting system were perceived. A direct positive effect was less financial worries. One important indirect effect mentioned by many indigent participants was an improvement in economic status due to better health ‘I went to the hospital many times. I was treated for free and I now notice that poverty has also reduced’(Female indigents, Tokombéré) ‘Now that I am cured I can do other activities like cultivate land again’(Female indigent, Tokombéré). Other indirect effects that were mentioned by a few indigents in a few groups were exposure to health and hygiene education and access to other services such as food and water. Key Informants also mentioned positive effects, particularly more motivated staff, work efficiency, more trainings and equipment and a better collaboration between the COSA and the facility ‘There is more dialogue between health staff and the COSA; there are no more secrets. We have regular meetings in which we develop our business plans together.’(Health personnel, Domayo).

Several negative effects were also identified. Although there were no direct indications of stigmatization, negative reactions of community members such as jealousy or incomprehension were perceived as disrupting by indigent participants ‘The neighbors are jealous, they don’t want to bring us to the facilities with their transport and if you don’t have transport you cannot get to the center’(Female indigent, Mayo-Ouldémé). One key informant remarked that due to labelling some indigents felt ‘privileged over other community members’(Facility director, Guili). In the non-indigent groups, feelings of injustice and jealousy were confirmed ‘It’s good to help those that don’t have any resources but why only select some?’ (Female non-indigent, Mayo-Ouldémé). In turn, some non-indigent participants noted that the health care fees had gone up the past year/months ‘I don’t really see a change; the fees have actually gone up. For instance, some medical fees have gone from 1000to 2000FCFA, for adults the fees have even gone up from 2000to 4000FCFA’(Female non-indigent, Douvangar) and that the facility was less flexible with giving loans ‘The hospital is not like before; a lot has changed. Before we used to be able to get loans for medicines now you have to have cash’(Male non-indigent, Tokombéré).

Key informants identified additional negative effects. Many mentioned an increase in workload, lack of staff and discussions/conflicts about the distribution of the performance bonuses ‘There is an increase in tasks which also increase the waiting time for patients’(Health personnel, Domayo). At the Goudjoumdélé facility key informants mentioned that targeting had led to more costs ‘PBF has influenced the cost of care. Indigents generally come to the center when the illness is severe and the costs often surpass the amount we get. We lose more than we gain’(Health personnel, Goudjoumdélé). Conversely, others mentioned that PBF had lowered the fees for patients and that the profitability of the centre had increased ‘With the arrival of PBF instead of paying 10 000 CFA, patients will be paying 2000or 5000FCFA which is already half’(Health personnel, Tokombéré).

Discussion

This study showed that within the targeting system in Northern Cameroon community health workers were able to identify very poor and vulnerable people with a minimal chance of leakage to non-poor people. Nevertheless, the system only reached a tiny proportion of the population and a substantial part of the population that can also be considered poor and socially vulnerable people was missed. Low a priori objectives and implementation problems are likely to explain this. Several positive and negative effects of the targeting system were identified. Indigents perceived improvements in economic status, access, quality and promptness of care while negative reactions (e.g. jealousy) of other community members towards indigents were perceived as negative effects.

Some methodological strengths and limitations need be addressed. A strength is that we collected data from different sources using different methods which allowed us to triangulate data (Pope and Mays 2000). The large number of interviews and FGDs that were conducted with different groups (indigents and non-indigents) were an additional strength. There were also some limitations. By conducting FGDs in several languages some information may have gotten lost during the translation process. Social desirability and response bias (i.e. more response from those indigents that attended the facilities) could have influenced the results found. Additionally, contextual factors such as increases in drug costs or changes in the PBF mechanisms and indicator pricing may have influenced the results found.

In line with other studies (Noirhomme et al., 2007; Ridde et al., 2010a, 2011a), we found that community health workers ‘are’ able to identify those people that are most vulnerable and poor and that leakage with this community-based approach was minimal. On the other hand, our study revealed that only a tiny proportion of the population (≤1%) was reached with the approach. We had expected larger percentages based on the literature. For instance, the proportion of the population in Northern Cameroon that falls in the poorest quintile (according to country-level cut-offs) is 54.8% (INS and ICF International 2012). Also, 5% of the Cameroonian population was estimated to be disabled in 2012 (INS and ICF International 2012). A study conducted in Burkina Faso, estimated that 10–20% of the population could be considered indigent (Ridde et al., 2010a).

We found that implementation problems probably exacerbated the (under)coverage. As noted by others (Davies and Taylor-Vaissey 1997; Grol and Grimshaw 2003; Grol et al. 2007), the implementation of new guidelines in routine health care practice is driven by a variety of inhibiting and enabling factors. For community-based targeting to succeed, all of these factors need to be considered (Grol et al. 2007). In Cameroon, financial incentives for motivating community health workers to implement the targeting system were considered insufficient given the increase in workload. Also, there was no transport to identify indigents. Financial disincentives and transport problems were also found to play a role in other community-based targeting systems in Africa (Ridde et al. 2010b, 2011a;Maluka, 2013). Grol et al. (2007) note that provision of resources, awards and (financial) incentives influence the volume of activities. At the individual level, adequate knowledge about the guidelines and positive attitudes are important (Grol et al. 2007). In our study area in Cameroon and in other similar settings (Ridde et al. 2010a;Maluka 2013), community health workers particularly targeted easily identifiable groups such as the elderly and orphans. Although this may reflect demographics, with rural-urban migration by young people leaving many elderly in rural areas without support (the so-called ‘rural exodus’) (Barbier et al. 1981) this may also reflect negative attitudes towards the current criteria (e.g. guidelines unclear, resistance to predefined criteria) or a lack of knowledge about the criteria. Last, there were social factors that were driving the implementation problems in Cameroon. Of importance was the finding that there was dispute about the distribution of performance bonuses and feelings of injustice. As a result, community health workers and health personnel were less motivated to perform well. A strong feeling of control and recognizing the output achieved is found to be crucial to successful implementation (Davies and Taylor-Vaissey 1997; Grol and Grimshaw 2003; Grol et al. 2007).

Despite the implementation problems identified, positive effects of the targeting system were perceived including improvements in access, quality and promptness of care as well as less financial worries and improvements in economic status for indigents. Nevertheless, lack of transport, distance to the health centres and poor knowledge about the targeting benefits continued to hamper indigents to seek care, as also reported by others Hardeman et al. (2004) and Ridde et al. (2011b).

The improvements in quality of care noted in this study, particularly in the area of hygiene and facilities, have been reported by other PBF studies (Basinga et al. 2011; Soeters et al. 2011). Conversely, we found that poor and vulnerable groups not registered as indigent perceived longer waiting times, less availability of staff, increased user-fees and less flexibility with loans. In a recent review (Gorter and Meessen 2013), several unintended side-effects of PBF were noted, including a neglect of non-numerated activities and adverse selection of patients. Although further research is warranted, our study may also indicate that vulnerable populations not directly targeted by PBF could be disadvantaged and fall by the wayside.

Lessons learned from implementation practice

This study showed that community health workers are able to identify very poor and vulnerable people with a minimal chance of leakage to non-poor people. It also shows that such a targeting system may improve access to care and perceived quality of care for the most vulnerable of society. Conversely, coverage rates were found to be very low, there were implementation problems and several negative effects of the system were perceived. Before discussing recommendations for improving the system, it’s important to address the issue of coverage. In situations of widespread poverty, such as in Northern Cameroon, where many of the non-indigents were hardly any better off than those identified as indigent by the programme, results achieved may not outweigh the cost of targeting. Hence, programme implementers should carefully consider the pros and cons of implementing such a targeting system since other strategies, such as social security schemes, might be more effective in achieving increase in access to care.

When implementing targeting systems, programme implementers are advised to base objectives/targets on evidence on the size of the target population, taking into account both social and economic vulnerability. Once these objectives are set, they should be carefully communicated to those working with them, ensuring they are not interpreted as a quota. When working with community health workers in a targeting system, it is essential to think about incentives, either in the form of money, trainings and/or transport (e.g. availability of a bike, car/moto). The extra workload for health care workers due to the system should be manageable. To ensure this, close attention needs to be paid to the context when estimating indicator pricing within PBF programmes so that costs are fully covered. This is likely to lead to more equal distribution of funds and enables health facilities to hire more staff. Last, programme implementers should consider investing in a comprehensive targeting system which includes a clear promotion component so that indigents are aware of the system, indigent identification cards, transport and accompaniment to the health centre, referrals and follow-up visits.

Conclusion

This study shows that a system of targeting the poorest of society in PBF programmes may help reduce inequalities in health care use, but design and implementation problems can lead to substantial under-coverage. Furthermore, remaining barriers to health care use (e.g. transport) and negative reactions towards indigents due to their status deserve attention.

Ethical issues

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus Medical Centre gave a ‘declaration of no objection’ for this study (MEC—2013-256). Additionally, the regional delegate of the Cameroonian Ministry of Health gave her permission for the study. The free and informed consent of the participants was attained on article. Participants were made aware of their voluntary participation and the right to withdraw at any moment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank André Zra for his immense help with coordinating the research activities on site and in Yaoundé. A further word of thanks goes out to all the respondents that participated in the FGDs and interviews.

Funding

This research was made possible through funding from Cordaid Grant number 109199.

Conflict of interest statement. Frank van de Looij and Hilda van ‘t Riet are employees of the funding agency.

References

- Bakeera SK, Wamala SP, Galea S. et al. 2009. Community perceptions and factors influencing utilization of health services in Uganda. International Journal of Equity Health 8: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier JC, Courade G, Gubry P. 1981. [The rural exodus in Cameroon]L’exode rural au Cameroun. Cah Orstom (Sci Hum) 18: 107–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H. et al. 2012. Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 379: 1225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basinga P, Gertler PJ, Binagwaho A. et al. 2011. Effect on maternal and child health services in Rwanda of payment to primary health-care providers for performance: an impact evaluation. Lancet 377: 1421–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerma JT, Bryce J, Kinfu Y, Axelson H, Victora CG. 2008. Mind the gap: equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health services in 54 Countdown countries. Lancet 371: 1259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDD. 2011. [Proposal for Performance Based Financing in the Diocese of Maroua] Proposition Financement Basé sur la Performance Diocèse de Maroua. Maroua: Comité Diocésain de Développement. [Google Scholar]

- CDD. 2012a. [Baseline report conducted in the context of the execution of PBF activities in the Diocese of Maroua-Mokolo] Rapport de l’étude de base dans le cadre de la mise en oeuvre des activités PBF dans le Diocèse de Maroua-Mokolo. Maroua: Comité Diocésain de Développement. [Google Scholar]

- CDD. 2012b. [Manual for the administrative, financial and accounting procedures] Manuel de procedures de gestion administrative, financiere et comptable. Maroua: Comité Diocésain de Développement. [Google Scholar]

- CDD. 2012c. [Report on the PBF kick-off workshop 19-24 March 2012 in Maroua] Rapport de la formation du lancement des activités PBF du 19 au 24 mars 2012 a Maroua. Maroua: Comité Diocésain de Développement. [Google Scholar]

- CDD. 2013. [Diocese of Maroua-Mokolo PBF health program: Activity execution guide] Diocese de Maroua-Mokolo PBF Santé: Guide d'execution des activités. Maroua: Comité Diocésain de Développement. [Google Scholar]

- CSDH. 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Davies DA, Taylor-Vaissey A. 1997. Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Canadian Medical Association Journal 157: 408–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche BG, Soeters R, Meessen B. 2014. Performance-Based Financing Toolkit, Washington DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. 2013. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter AC, Ir P, Meessen B. 2013. Evidence Review, Results-Based Financing of Maternal and Newborn Health Care in Low- and Lower-middle-Income Countries. Study commissioned and funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the sector project PROFILE at GIZ – Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. 2003. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 362: 1225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Bosch M, Hulscher M, Eccles M, Wensing M. 2007. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. The Milbank Quaterly 85: 93–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman W, Van Damme W, Van Pelt M. et al. 2004. Access to health care for all? User fees plus a Health Equity Fund in Sotnikum, Cambodia. Health Policy and Planning 19: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSKN. 2007. Final Report of the Health Systems Knowledge Network of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Statistique (INS) & ICF International. 2012. [Demographic Health Survey and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey Cameroon] Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples du Cameroun. Calverton, MD: INS and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- Maluka SO. 2013. Why are pro-poor exemption policies in Tanzania better implemented in some districts than in others? International Journal of Equity Health 12: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noirhomme M, Meessen B, Griffiths F. et al. 2007. Improving access to hospital care for the poor: comparative analysis of four health equity funds in Cambodia. Health Policy and Planning 22: 246–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Mays N. 2000. Qualitative Research in Health Care . London: BMJ Books. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridde V, Haddad S, Nikiema B. et al. 2010a. Low coverage but few inclusion errors in Burkina Faso: a community-based targeting approach to exempt the indigent from user fees. BMC Public Health 10: 631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridde V, Yaogo M, Kafando Y. et al. 2011a. Targeting the worst-off for free health care: a process evaluation in Burkina Faso. Evaluation Program Planning 34: 333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridde V, Yaogo M, Kafando Y. et al. 2011b. Challenges of scaling up and of knowledge transfer in an action research project in Burkina Faso to exempt the worst-off from health care user fees. BMC International Health and Human Rights 11: S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridde V, Yaogo M, Kafando Y. et al. 2010b. A community-based targeting approach to exempt the worst-off from user fees in Burkina Faso. Jorunal of Epidemiology Community Health7 64: 10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeters R, Peerenboom PB, Mushagalusa P, Kimanuka C. 2011. Performance-based financing experiment improved health care in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Health Affairs 30: 1518–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2012. Millennium Development Indicators: Country and Regional Progress Snapshots. Retrieved from: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/ on 15th July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United nations. 2013. MDGs Progress Chart 2013. Geneva: Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, Barros AJ, Axelson H. et al. 2012. How changes in coverage affect equity in maternal and child health interventions in 35 Countdown to 2015 countries: an analysis of national surveys. Lancet, 380: 1149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter S, Adjei S. 2007. Start-stop funding, its causes and consequences: a case study of the delivery exemptions policy in Ghana. International Journal of Health Planning Manage 22: 133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter S, Kessy FL, Lindahl AK. 2012. Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD007899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonga A, A V. 1995. Enquête sur les budgets familiaux dans les Monts Mandara Extrême-Nord Cameroun. Comité Diocésain de Développement (CDD). [Google Scholar]

- Ziebe R, Vaggai D. 2013. [Indigent criteria and targeting procedures in the health facilities of the Diocese Maroua Mokolo] Critère d’indigence et procédure de ciblage dans les formations sanitaires du Diocèse de Maroua Mokolo. Maroua: Institut Superieur du Sahel, Université de Maroua, Maroua, Cameroun. [Google Scholar]