Abstract

Introduction

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often have multiple hospitalisations because of exacerbation. Evidence shows disease management programmes are one of the most cost-effective measures to prevent re-hospitalisation for COPD exacerbation, but lack implementation and economic appraisal in China. The aims of the proposed study are to determine whether a hospital outreach invention programme for disease management can decrease hospitalisations and medical costs in patients with COPD in China. Economic appraisal of the programme will also be carried out.

Methods and analysis

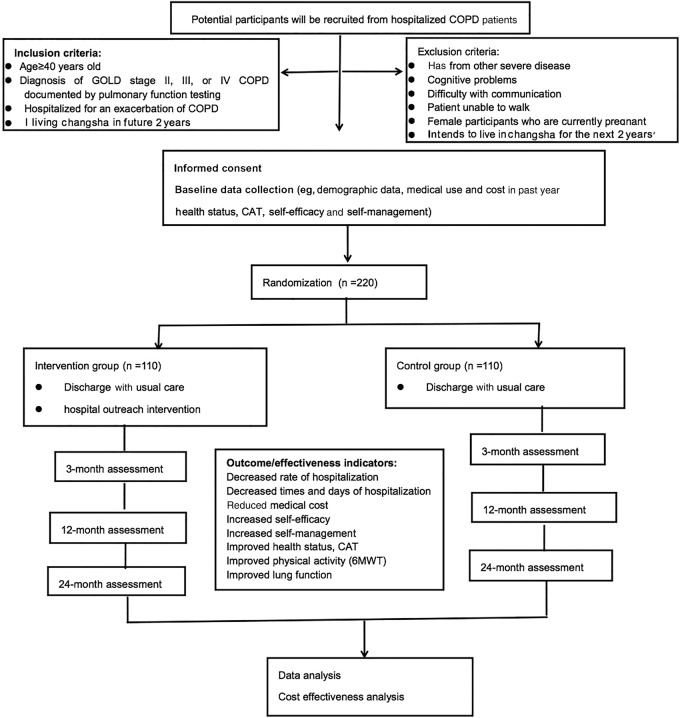

A randomised single-blinded controlled trial will be conducted. 220 COPD patients with exacerbations will be recruited from the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China. After hospital discharge they will be randomly allocated into an intervention or a control group. Participants in the intervention group will attend a 3-month hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation intervention and then receive a home-based programme. Both groups will receive identical usual discharge care before discharge from hospital. The primary outcomes will include rate of hospitalisation and medical cost, while secondary outcomes will include mortality, self-efficacy, self-management, health status, quality of life, exercise tolerance and pulmonary function, which will be evaluated at baseline and at 3, 12 and 24 months after the intervention. Cost-effectiveness analysis will be employed for economic appraisal.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (IRB2014-S159). Findings will be shared widely through conference presentations and peer-reviewed publications. Furthermore, the results of the programme will be submitted to health authorities and policy reform will be recommended.

Trial registration number

Chi CTR-TRC-14005108; Pre-results.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a hospital outreach intervention programme to prevent re-hospitalisations and decrease medical costs in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in China.

Economic appraisal of the hospital outreach intervention programme will be carried.

The aim of the study is to develop a disease management model suitable for COPD patients in China.

Recruitment of participants from a single clinic will limit the generalisability of the study findings to patients in similar hospitals.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and results in an economic and social burden.1 The WHO and World Bank reported that COPD is the fourth leading cause of death and has the fifth highest disease burden globally.2 The prevalence of COPD is 4.96% in the USA.2 The problem is even more severe in China, which has over 300 million cigarette smokers.3 The prevalence of COPD in China is 8.2%,4 accounting for 1.28 million deaths annually, which is higher than for coronary heart disease (1 million). It is the only major disease whose mortality rate is increasing.2 4 Exacerbation of COPD is defined as an acute event characterised by a worsening of the patient's respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variations and leads to a change in regular medication.5–7 Exacerbations have a significant impact on COPD patients such as increasing the long-term decline in lung function and resulting in a deterioration in health status and risk of death.8–12 Furthermore, exacerbation is a major cause of COPD patients requiring hospital admission,11 which hospitalisations account for 70% of the treatment costs for this disease.13–15

Researchers have previously explored the interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with COPD, such as pulmonary rehabilitation, outreach nursing, multidisciplinary care, patient self-management, patient counselling and education, and case management.16 17 The effectiveness of these interventions has also been investigated: original studies reported that these programmes improved exercise capability and health-related quality of life, and decreased hospitalisations for COPD exacerbation in patients.18–20

Implementing an outreach system has been generally accepted as an effective means of providing support services to improve chronic disease management in the outpatient setting.21

Currently, COPD patients in China receive healthcare only in hospitals with no outreach follow-up or services provided after discharge, although hospital outreach interventions have been a focus of public hospital reforms undertaken by the Ministry of Health since 2009. Some hospital–community integrated programmes for COPD have been conducted in China and their effectiveness verified.4 22 In these programmes, care was primarily provided by community healthcare providers, so the intervention is suitable for patients with mild to moderate disease but not patients with severe disease. Patient adherence to treatment is very important and includes taking the correct medication, pulmonary rehabilitation, smoking cessation, and self-management. It is therefore key to develop a hospital outreach system to ensure a continuum of hospital care and maintain patients’ motivation regarding adherence to healthy behaviour.

Economic analyses of healthcare interventions are increasingly necessary, especially since skilled allocation of scarce healthcare resources is particularly important in a developing country. Cost-effectiveness analysis of several COPD disease management programmes has been carried out previously.23 24 A recent meta-analysis showed that such programmes can lead to significant savings in hospital costs and total healthcare costs.25 However, prior to our study, no randomised controlled trials of the effect and the costs of hospital outreach intervention programmes for patients with COPD in China were available.

The proposed study seeks to develop, deliver and evaluate a hospital outreach invention programme for patients with COPD, aiming at preventing exacerbations and thus reducing readmissions and medical costs. It is hypothesised that the hospital outreach intervention programme will provide cost-effective disease management by improving adherence to medication, physical exercise, self-management and smoking cessation in patients with COPD, resulting in fewer exacerbations, less hospitalisations and lower medical costs. This will be tested in this study.

Goal and objectives

The overall goal of the project is to develop, deliver and evaluate a hospital outreach intervention for patients with COPD. There are four specific objectives:

To coordinate multidisciplinary experts in establishing a protocol for a hospital outreach intervention;

To provide a hospital outreach intervention programme after discharge for patients with COPD;

To evaluate the effectiveness of a hospital outreach intervention programme in preventing re-hospitalisation and decreasing medical cost;

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of this programme.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

A randomised single-blind controlled trial will be conducted and economically evaluated. The research protocol of this study will be registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.chictr.org.cn).

Setting

This study will be conducted at the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University in Changsha city, Hunan province. This hospital is located in the west of Changsha city. It is a general hospital with 1800 beds and mainly provides healthcare for the 600 000 residents in the surrounding district, with an estimated of 48 000 individual patients hospitalised every year. On average, 100–120 patients with COPD are discharged every month following hospitalisation for a COPD exacerbation.

Participants

Hospitalised COPD patients in the Third Xiangya Hospital of the Central South University will be invited to participate. Entry criteria will be as follows: (1) age ≥40 years; (2) diagnosis of Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage II, III or IV COPD documented by pulmonary function testing; (3) hospitalised for an exacerbation of COPD; and (4) not intending to move from Changsha city within the next 2 years. Exclusion criteria will be: (1) has other severe disease, such as unstable cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, cancer or uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension; (2) presence of cognitive problems; (3) difficulty with communication, such as blindness or deafness; (4) unable to walk and so hindered from undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation focused on upper extremity conditioning; and (5) current pregnancy.

Preparation

We undertook several approaches to explore different trial designs. First, a draft of the protocol was written based on the guidelines.1 Second, the draft protocol was reviewed by five experts in respiratory medicine, nursing, nutrition, psychology and rehabilitation. Third, the protocol was revised following suggestions from the experts. Finally, a pilot was completed to test various elements prior to study commencement.

Recruitment

Figure 1 shows the proposed study flow. Recruitment will be undertaken among patients with COPD hospitalised for exacerbations in the Third Xiangya Hospital of the Central South University. Two main recruiting approaches will be used. First, potentially eligible patients will be identified through a review of electronic medical records in the hospital information system. The physicians of eligible patients will be notified of their patients' eligibility, and then asked for permission to enrol these patients in the study. Thereafter, the physician and researcher will approach the patients for screening, consent and a baseline visit. Second, physicians will be asked to identify patients with COPD on the wards. Study investigators will explain the study rationale, significance and procedures to the physicians each month. At this time, physicians will be given a business card that lists the eligibility criteria and contact information for the researcher. Once a patient fulfilling the inclusion criteria is identified, the researcher will approach the patient and complete the eligibility screen, consent and baseline data collection.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of trial study flow and participant numbers. CAT, COPD Assessment Test; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 6MWT

Sample size and calculation

A sample size of 220 is required, consisting of 110 patients for an intervention group and 110 for a control group. This number was calculated by power analysis using PASS software (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA). One intervention group and one control group of equal size and two-tailed hypothesis testing is assumed. The power is set at >0.8, while α is 0.05. According to a literature review, self-reported health status is independently associated with COPD hospitalisations.26 Self-rated health status was provided as fair or poor versus good, very good, or excellent (from SF-36 tool) (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.23). Overall, 10.8% of patients with no hospitalisation in the past 12 months reported they had a fair/poor health status, while 26.7% of patients with at least one hospitalisation reported their health status was fair/poor.26 The calculated sample size is 92 for each group. To account for an attrition rate of 20%, the final sample size will be 220.

Intervention description

Hospital outreach intervention

The intervention will be divided into two parts. (1) Hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation will be provided for the first 3 months (table 1): an area in the hospital large enough for about 20 patients to perform physical exercises will be rented. Free door-to-door transport will be provided to facilitate participants. (2) Home-based programmes will consist of two sections: (i) after the 3 months of hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation, patients will be instructed to continue the same physical exercises at home without supervision and will record their physical exercise each week on a special sheet; and (ii) nurses will contact patients every 1–2 weeks to maintain patient motivation to adhere to physical exercise, smoking cessation, and long-term oxygen and inhaler use, and will provide psychosocial support if necessary.

Table 1.

Major elements of the hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme during the first 3 months

| Item | Content | Frequency | Interventionist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical exercise | Upper body exercise: 15–30 min of lifting weights Lower body exercise: 15–30 min on a cycle ergometer |

Twice a week for 30–60 min each time | Physiotherapists | |

| Modified Taijiquan exercises | Once a week for 30–60 min | Taijiquan instructor, RA | ||

| Smoking cessation | Group intervention | 3 Sessions | Psychologist, nurse | |

| Individual intervention | Once or twice a week | |||

| Self-management education | COPD knowledge, symptom management, pulmonary rehabilitation treatment and drug utilisation, benefits of physical exercise, nutrition and diet, long-term oxygen therapy |

7 Sessions | Multidisciplinary team: physician, nutritionist, nurse | |

| Psychosocial support | Group activity to facilitate communication among patients; suggesting coping strategies; individual counselling when needed |

2 Sessions | Psychologist, nurse |

In our preliminary study, we reduced the number of traditional Taijiquan procedures from 24 to 6 and verified its effectiveness. Adherence to the intervention was defined as attendance at 75% or more sessions.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RA, research associate.

Discharge usual care

Both groups will be given instruction on self-management, exercise and seeking healthcare when necessary by a respiratory nurse before discharge from hospital. All participants will receive a pamphlet on COPD management.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants will be randomised after consent and the collection of baseline data. Recruitment staff will not have access to the results of randomisation prior to recruiting the subject. The allocation sequence will be generated and released to the interventionist on a case-by-case basis by an independent organisation which specialises in supplying randomly generated sequences for research. The randomisation sequence will be recorded. Patients will be informed of the results of randomisation by a research associate in person or by phone after discharge. At that time, the research associate will discuss the intervention schedule and answers any questions.

Given the nature of the intervention, this will be a single-blind trial as blinding the participants is not feasible and the interventionist will know that all those contacted are in the intervention arm. The statistician will be blind to individual results during the trial and the allocation-to-trial-arm coding will only be revealed when the data set is sealed. The interventionist and supervisors will be blind to the baseline and follow-up measures and will not be involved in the delivery of the intervention. Anonymised responses will be entered onto the database by an individual not connected to the project.

Safety during exercise

Only patients able to undertake exercise safely will be considered for enrolment in the study. Consequently, no adverse events such as SpO2 falling below 80%, angina or myocardial infarction should occur during exercise. The following procedure will be followed: (1) at the time of recruitment, participants' inpatient files and self-reports will be used to screen for health conditions; those with comorbidities (such as unstable cardiovascular disease) that prevent participation in exercise be excluded from the study; (2) during supervised training, participants’ heart rate, SpO2 and dyspnoea will be monitored by a research assistant. If SpO2 falls below 90%, oxygen supplementation will be provided to maintain SpO2 at 90% or above. Exercise must be stopped immediately if there is chest pain, new cardiac arrhythmia, dizziness or nausea. The patient should rest if their heart rate approaches the participant’s age predicted maximum), SpO2 falls below 85% or there is marked wheeze. Some first-aid medications and facilities will be provided at the exercise site. (3) The prescription for each home exercise (eg, duration for endurance exercise, and weight and number of repetitions for resistance exercise) will be individualised based on performance during the supervised sessions.

Outcome evaluation

Primary outcome measures

1. Admissions to hospital

Data on hospitalisation (number of hospitalised persons, number of times admitted per person, mean length of hospital stay per person) will be obtained from the hospital record through the hospital information system and reconciled with patient follow-up records and patient self-report.

2. Medical cost

Information on medical cost will be also obtained by searching hospital records and reconciled with patient follow-up records and patient self-report.

Secondary outcome measures

Mortality

Health status, including dyspnoea, exercise tolerance, quality of life and lung function

Level of self-efficacy

Level of self-management.

Information on all-cause mortality and number of deaths will be obtained from hospital records through the hospital information system and reconciled with patient follow-up records.

Dyspnoea will be measured using the modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale (MMRC).27 The MMRC measures functional limitation resulting from dyspnoea on a scale of 0–4. The Chinese version of the scale has been tested and used.

Exercise tolerance will be assessed using the 6 min walk test (6MWT).28 The 6MWT will be conducted according to the protocol recommended by American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines to measure functional exercise capacity.29 This test measures the self-paced distance that a patient can quickly walk on a flat, hard surface in a period of 6 min.30 Two tests will be performed, with the greatest distance recorded.

Quality of life will be measured with the COPD Assessment Test (CAT). The CAT is a short, simple questionnaire for assessing the impact of COPD on health status.31 The scale consists of eight items and is scored from 0 to 40, where 0–10 indicates slight impact and 31–40 indicates very serious impact. The questionnaire has been used in a Chinese population.

Lung function will be tested by spirometry using the same machine and by the same technician for all patients following a standard protocol.32 Parameters will include forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), percentage predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) and percentage predicted vital capacity.

Self-efficacy will be measured using the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adapted Index of Self-Efficacy (PRAISE).33 The 15-item PRAISE is in English and items are scored from 1 to 4. Researchers will translate PRAISE into Chinese and validate it.

Self-management will be measured using the COPD Self-Management Scale (CSMS),34 which includes five domains: symptom management, daily life management, emotion management, information management and self-efficacy. This scale has been used in a Chinese population.

Analysis of economic data

Cost analysis

- Intervention cost

- Personnel cost: the activities and number of hours spent by personnel will be recorded by the programme provider. The cost per subject will then be calculated by dividing the overall cost by the total number of participants.

- Materials needed for the intervention such as renting a space for Taijiquan exercises and health education; CDs; TV; pamphlets.

- Transportation: transport of patients to the hospital so they can participate in the programme.

- Communication: telephone calls to follow-up patients and maintain patient motivation.

- Medical costs of patients (COPD and COPD-related medical costs)

- Total inpatient cost

- Total outpatient cost

- Medication cost.

Outcome analysis

Mortality rate

- Physical outcome

- Pulmonary function

- Exercise tolerance: 6MWT

Quality of life

- Smoking status

- Smoking cessation

- Decreased number of smoked cigarettes

Utilisation of healthcare (number of hospitalised persons, number of times admitted per person, mean length of hospital stay per person)

- Cost saving

- Total cost difference between the intervention and control groups during the pre/post intervention period.

- Inpatient cost savings for the intervention group.

Economic analysis

A difference-in-difference model will be used. Cost and outcomes will be modelled individually as dependent variables. The following will be used: a dummy variable to indicate 1 as the intervention (I) and 0 as control as a key independent variable, a pre-post (P) dummy variable (1 is post, 0 is pre) and an interaction variable (I×P) to account for the pre/post difference, plus other confounding factors such as stage of COPD, age, gender, education, as other independent variables. The model is as follows:

Y is the cost or outcome variable. The coefficient of I is the difference between intervention and control, and P is the difference between pre and post, while the coefficient of I×P is the difference between intervention and control as well as pre and post. The coefficient will show the net effect of the intervention.

Cost-effectiveness comparison

Cost saving ratio: Every Chinese yuan of intervention cost spent on the intervention group, how many Chinese yuan of COPD and COPD-related medical cost would be saved.

Data collection

The data will be collected before and 3, 12 and 24 months after the intervention for the intervention group. For the control group, the data will be collected at the same time points as the intervention group.

Data analysis

SAS, STATA and Excel software will be used for statistical analysis. Equivalence will be examined at group assignment to the intervention and control groups using the Mann-Whitley U test, χ2 test, t-test or ANOVA. Clinical outcomes will include the indicators of self-efficacy, self-management, 6MWT, pulmonary function, perceived health status and quality of life. For the intervention and control groups, the indicators at baseline and at 3, 12 and 24 months will be compared with repeated measures ANOVA. Comparison of these outcome indicators between the intervention and control groups will be conducted using the t-test. The primary outcomes will include hospitalisation and medical costs. The rate of hospitalisation will be calculated as follows: rate=hospitalised persons×hospitalised days/observed persons×observed days. The effects on hospitalisation rate will be tested with the χ2 test. The effects on medical cost will be tested with the t-test.

Intention to treat

Outcome will be analysed on the basis of intention to treat (ITT). First, the principles of ITT will be applied to test the effects of attrition, meaning that all patients who have been randomised will be included in the analysis. Missing endpoints will be imputed using the expectation-maximisation (EM) algorithm. To gauge the robustness of the outcomes, this analysis will be repeated using the multiple-imputation approach. Second, propensity score analysis will also be employed using a logistic model (1 for adherence and 0 for attrition; 1 for intervention and 0 for control) to predict the probability of being in adherence/intervention. The predicted variable will then be used to replace the attrition/control dummy variable.

Data management

Only the principal investigator and the research coordinator will have access to the database during the study period. All data will be recorded by remote data entry into a web-based electronic case report form developed for the study by the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. The electronic case report form data will be anonymous and will identify study participants by their assigned study numbers only. All missing data, possible duplications and data outside preset limits for each parameter will be queried by the management centre, and will be internally validated before database lock. Participant files will be maintained in storage for 3 years after completion of the study. The data manager will respond by checking the original forms for inconsistency, checking other sources to determine the correct data, and modifying the original (paper) form by entering a response to the query. Note that it will be necessary for data managers to respond to each query received in order to obtain closure on the queried item.

Study steering committee

The study steering committee will consist of one principal investigator, three physicians and two representatives from the data monitoring centre, and will be responsible for all quality control activities, assessing adherence to the trial protocol, enrolment, adverse events and compliance reports, and making the final decision to terminate the trial. The committee will hold a seminar every month to report on the progress of the programme and to discuss any problems and their solutions.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The study has been approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. Before the study, participants will be told about the benefits, risks, rights and responsibility of the programme and the informed consent form will be signed. During the research, the participants will have full freedom to participate or withdraw at any time. The privacy of participants will be maintained and all of the information will be confidential. Usual health education on the management of stable COPD will be delivered to patients in the control group before discharge. If any patient needs help, they can access appropriate professional assistance.

Dissemination

Findings will be shared widely through conference presentations and peer-reviewed publications. Furthermore, the results of the programme will be submitted to health authorities and policy reform will be recommended.

Discussion

Our research project aims to develop, implement and evaluate a hospital outreach intervention programme suited to the needs of Chinese patients with COPD and to evaluate it economically. This study will address an important problem: although awareness of COPD is increasing in China, healthcare management still focuses on the acute stage during hospitalisation and relies primarily on pharmacological treatment while the management of stable disease is neglected.35 We hope to offer some strategies to strengthen disease management in COPD patients.

Original studies and systematic review have analysed the cost-effectiveness of many disease management programmes for COPD.36–38 However, as our programme will be different from previous projects, a specific economic evaluation will need to be carried out. First, we will analyse the consumption of health services by 220 patients with COPD over 24 months. In most previous studies, the follow-up period for assessing the effectiveness of disease management in COPD lasted 12 months or less,38 so we will have a relatively long observation period. Second, the cost estimates are based on reliable sources. Third, all costs associated with the intervention programme will be identified and measured.

This study will allow us to ascertain whether the hospital outreach intervention programme can prevent exacerbations, reduce re-hospitalisation, decrease medical costs, be cost-effective, increase self-efficacy, facilitate self-management, promote exercise tolerance, improve health status and lung function, and increase the quality of life of COPD patients in China.

The results of our study will contribute information on the effectiveness of a hospital outreach intervention programme for patients with COPD, provide better understanding and management of COPD, and raise the question of whether the programme could be extended to other chronic diseases. A summary report of the programme will be submitted to the health authorities and policy reform will be recommended.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the entire staff of the respiratory ward and rehabilitation centre of the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University for their help. We also like to express our gratitude to Professor Zhang Jianyong and Professor Cheng Ling for their support in developing the intervention.

Footnotes

Contributors: JY is principal investigator and was involved in study design and conception, manuscript preparation and editing. LW was involved in writing the protocol, editing the manuscript, setting up the trial, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. CL was involved in refining trial design, and setting up the trial. HY was involved in designing and setting up the trial. XW was involved in the design of the trial, and analysis and interpretation of data. BY was involved in designing and setting up the trial. QL was involved in setting up the trial and acquisition of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was provided by the China Medical Board (CMB grant number: 12-115).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (IRB2014-S159).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256–76. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannino DM. COPD: Epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality and disease heterogeneity. Chest 2002;121(Suppl 5):121S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Au WW, Su D, Yuan J. Cigarette smoking in China: public health, science, and policy. Rev Environ Health 2012;27:43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong NS. Chinese science and technological workers should play roles in COPD prevention. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis 2009;32:241–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Roisin R. Toward a consensus definition for COPD exacerbations. Chest 2000;117:398S–401S. 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_2.398S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J Suppl 2003;41:46s–53s. 10.1183/09031936.03.00078002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celli BR, Barnes PJ. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2007;29:1224–38. 10.1183/09031936.00109906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002;57:847–52. 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groenewegen KH, Schols AM, Wouters EF. Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2003;124:459–67. 10.1378/chest.124.2.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer S, Calverley PM, Burge PS et al. Impact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPD. Eur Respir J 2004;23:698–702. 10.1183/09031936.04.00121404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yohannes AM, Baldwin RC, Connolly MJ. Predictors of 1-year mortality in patients discharged from hospital following acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Age Ageing 2005;34:491–6. 10.1093/ageing/afi163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet 2007;370:786–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61382-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan MD. Preventing hospital admissions for COPD: role of physical activity. Thorax 2003;58:95–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer S, Jones PW. Time course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Thorax 2003;58:589–93. 10.1136/thorax.58.7.589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almagro P, Calbo E, Echagüen AOD et al. Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest 2002;121:144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faxon DP, Schwamm LH, Pasternak RC et al. Improving quality of care through disease management: principles and recommendations from the American Heart Association's Expert Panel on Disease Management. Circulation 2004;109:2651–4. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128373.90851.7B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casas A, Troosters T, Garcia-Aymerich J et al. Integrated care prevents hospitalisations for exacerbations in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2006;28:123–30. 10.1183/09031936.06.00063205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:585–91. 10.1001/archinte.163.5.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Staeger P, Bridevaux PO et al. Effectiveness of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-management programs: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2008;121:433–43. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denberg TD, Lin CT, Myers BA et al. Improving patient care through health-promotion outreach. J Ambul Care Manage 2008;31:54–65. 10.1097/01.JAC.0000304102.30496.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoogendoorn M, van Wetering CR, Schols AM et al. Is INTERdisciplinary COMmunity-based COPD management (INTERCOM) cost-effective? Eur Respir J 2010;35:79–87. 10.1183/09031936.00043309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steuten LM, Lemmens KM, Nieboer AP et al. Identifying potentially cost effective chronic care programs for people with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon 2009;4:87–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boland MR, Tsiachristas A, Kruis AL et al. The health economic impact of disease management programs for COPD: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2013;13:40. 10.1186/1471-2466-13-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benzo RP, Chang CC, Farrell MH et al. Physical activity, health status and risk of hospitalization in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 2010;80:10–18. 10.1159/000296504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chhabra SK, Gupta AK, Khuma MZ. Evaluation of three scales of dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Thoracic Med 2009;4:128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;166:111–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solway S, Brookes D, Lacasse Y et al. A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 2001;119:256–70. 10.1378/chest.119.1.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P et al. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller M R, Hankinson J, Brusasco V et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincent E, Sewell L, Wagg K et al. Measuring a change in self-efficacy following pulmonary rehabilitation: an evaluation of the PRAISE tool. Chest 2011;140:1534–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang C, Wang W, Li J et al. Development and validation of a COPD self-management Scale. Respir Care 2013;58:1931–6. 10.4187/respcare.02269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Y, Hu G, Wang D et al. Community based integrated intervention for prevention and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Guangdong, China: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c6387 10.1136/bmj.c6387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallefoss F, Bakke PS. Cost–benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of self-management in patients with COPD—a 1-year follow-up randomized, controlled trial. Respir Med 2002;96:424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paré G, Poba-Nzaou P, Sicotte C et al. Comparing the costs of home telemonitoring and usual care of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Res Telemed 2013;2:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lemmens KM, Nieboer AP, Huijsman R. A systematic review of integrated use of disease-management interventions in asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2009;103:670–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]