Abstract

Objective

To develop a theoretical model concerning male victims' processes of disclosing experiences of victimisation to healthcare professionals in Sweden.

Design

Qualitative interview study.

Setting

Informants were recruited from the general population and a primary healthcare centre in Sweden.

Participants

Informants were recruited by means of theoretical sampling among respondents in a previous quantitative study. Eligible for this study were men reporting sexual, physical and/or emotional violence victimisation by any perpetrator and reporting that they either had talked to a healthcare provider about their victimisation or had wanted to do so.

Method

Constructivist grounded theory. 12 interviews were performed and saturation was reached after 9.

Results

Several factors influencing the process of disclosing victimisation can be recognised from previous studies concerning female victims, including shame, fear of negative consequences of disclosing, specifics of the patient–provider relationship and time constraints within the healthcare system. However, this study extends previous knowledge by identifying strong negative effects of adherence to masculinity norms for victimised men and healthcare professionals on the process of disclosing. It is also emphasised that the process of disclosing cannot be separated from other, even seemingly unrelated, circumstances in the men's lives.

Conclusions

The process of disclosing victimisation to healthcare professionals was a complex process involving the men's experiences of victimisation, adherence to gender norms, their life circumstances and the dynamics of the actual healthcare encounter.

Keywords: Violence, Abuse, Masculinity, Gender, Help-seeking

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to explore men's experiences of disclosing victimisation to healthcare professionals in Sweden.

Men with experiences of different kinds of violence victimisation from different kinds of perpetrators were included in the study, mirroring a true diversity in experiences among male patients.

Since we chose to include men with experiences of different kinds of violence victimisation, we could not identify violence-specific processes of disclosing. Instead of eliciting nuances, we captured core features of the process of disclosing.

Introduction

Exposure to different kinds of interpersonal violence (eg, intimate partner violence, childhood abuse and peer victimisation) is prevalent and is associated with poor health in both sexes.1–5 However, only few victims tell healthcare professionals about their victimisation. In a Swedish population-based study by the National Centre for Knowledge on Men's Violence Against Women, only 20% of women and men subjected to physical violence in adulthood and 5–10% of women and ∼1% of men subjected to sexual violence in adulthood had sought professional help from a counsellor, a psychologist or a doctor.6

Different kinds of victimisation are intertwined, and many victims of violence have experienced more than one kind of violent behaviour (sexual, physical and emotional) and/or violence from more than one kind of perpetrator (family, partner and other).3 4 7–9 Yet, research on help-seeking and healthcare response to victims of violence is often focused on a specific kind of violence, most commonly intimate partner violence or sexual abuse.10–12 Also, though some studies have focused on the help-seeking experience of male victims of intimate partner violence,13 help-seeking among male victims has not been as thoroughly investigated as among female victims. This study explores the process of disclosing experiences of victimisation to healthcare professionals in Sweden for men subjected to different kinds of violence from different kinds of perpetrators.

Theories of help-seeking behaviour have been applied to interpersonal violence in general14 15 and more specifically to female victims of intimate partner violence.16 It has been emphasised that emotions (eg, shame due to being victimised), reactions and attitudes from relatives and friends, and wider social processes (eg, societal norms that lead to the acceptance of violence within an intimate partner relationship) influence the victims' help-seeking processes.14–16 These theories of help-seeking behaviours either focus only on women or do not discuss gender.14–16 However, interpersonal violence and help-seeking are gendered processes.13 17 In general, men and women are exposed to different kinds of violence associated with different characteristics and perpetrators.3 8 18 For example, though some men are subjected to serious violence from their intimate partners,19 20 women are, on a group level, exposed to more severe and serious forms of intimate partner violence than are men.18 21

Gender also affects the response that men receive when seeking help. For example, in one US study investigating the help-seeking experiences of men who have sustained violence from a female intimate partner, a large proportion of men report being referred to batterer programmes when seeking help as victims at domestic violence agencies.13

Research on addressing violence with male patients within the healthcare system is scant, but men have been found to be less likely than women to discuss their victimisation.22–24 One study of Swedish emergency departments found that very few had routines in place for identifying victims of violence, and none were prepared to care for male victims of violence.25 Male victims' experiences of disclosing violence to healthcare professionals have never been explored in Sweden, but are essential for improving the healthcare systems' response to male victims of different kinds of violence.

Aim

The aim of this study was to develop a theoretical model concerning male victims' processes of disclosing experiences of victimisation to healthcare professionals in Sweden.

Theoretical framework—hegemonic masculinities

Gender, and more specifically masculinity, can be constructed in multiple ways. Practices of masculinity that are more associated with authority and social power than others constitute what is referred to as hegemonic masculinity. The practices that are characteristic of hegemonic masculinity differ, depending on the cultural context but can be for instance self-dependence.26 Men who endorse hegemonic masculinity have been found to be less prone to seek psychological, as well as medical, help.27 28 In the current study, we use the concept of hegemonic masculinity as an interpretative tool.

Method

Methodology

Constructivist grounded theory as described by Charmaz29 was used. The analytical approach in constructivist grounded theory is similar to original grounded theory created by Glaser and Strauss.30 However, the latter builds on positivist assumptions, whereas constructivist grounded theory asserts that knowledge is contextually created together by the researcher and the informants.29 Contrary to the original grounded theory, the end product in constructivist grounded theory is not necessarily an overriding core category. Rather, the practice of theorising in constructivist grounded theory gives priority to revealing patterns and connections rather than to linear reasoning and emphasises understanding rather than explanation.29

Participants

Informants were recruited from respondents in a quantitative study of being subjected to interpersonal violence, ill-health and help-seeking behaviour that was conducted among men and women in the general population (n=1510, response rate 37%) and at two primary healthcare centres (n=129, response rate 70%) in Sweden in 2012. That study will be reported elsewhere. Respondents answered the NorVold Abuse Questionnaire (NorAQ), which included questions about lifetime experiences of emotional, physical and sexual violence as well as questions about the participant's health and help-seeking.31 32 The questions used to operationalise violence can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Questions about exposure to interpersonal violence in NorAQ

| Emotional violence | |

| Mild | Have you experienced anybody systematically and for a long period trying to repress, degrade or humiliate you? |

| Moderate | Have you experienced anybody systematically and by threat or force trying to limit your contact with others or totally control what you may and may not do? |

| Severe | Have you experienced living in fear because somebody systematically and for a long period threatened you or somebody close to you? |

| Physical violence | |

| Moderate | Have you experienced anybody hitting you with his/her fist(s) or with a hard object, kicking you, pushing you violently, giving you a beating, thrashing you or doing anything similar to you? |

| Severe | Have you experienced anybody threatening your life by, for instance, trying to strangle you, showing a weapon or knife, or by any other similar act? |

| Sexual violence | |

| Mild | Has anybody against your will touched parts of your body other than the genitals in a “sexual way” or forced you to touch other parts of his or her body in a ‘sexual way’? |

| Mild/sexual humiliation | Have you in any other way been sexually humiliated; for example, by being forced to watch a pornographic movie or similar against your will, forced to participate in a pornographic movie or similar, forced to show your body naked or forced to watch when somebody else showed his/her body naked? |

| Moderate | Has anybody against your will touched your genitals, used your body to satisfy him/herself sexually or forced you to touch anybody else's genitals? |

| Severe | Has anybody against your will put his penis into your vagina, mouth or rectum or tried any of this, or put in or tried to put an object or other part of the body into your vagina, mouth or rectum? |

The word ‘vagina’ was omitted from the male version of the questionnaire.

NorAQ, NorVold Abuse Questionnaire.

Men who answered ‘Yes’ to at least one of the questions about violence and reported that they either had talked to a healthcare provider about their victimisation or had wanted to do so were eligible for this study. Experiences of disclosing victimisation to professionals who work within healthcare services, as well as healthcare professionals such as therapists and counsellors who work within social services, were included in the present study. Table 2 provides the background characteristics of the interviewed men. One man was recruited from one of the primary healthcare centres and 11 were recruited from the random population sample. Two potential informants could not participate for practical reasons, and one declined participation because he had put his experiences behind him and did not want to revisit them (also included in table 2).

Table 2.

Background characteristics of the 12 interviewed men and those who declined participation

| No | Age | Kind of violence | Duration/frequency of victimisation | Perpetrator: partner, family member or someone else | Disclosed to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informants | |||||

| 1 | 61 | Emotional | >2 years | Partner | Physician and nurse, psychiatric care |

| Physical | 1–2 times | Someone else | |||

| 2 | 42 | Emotional | >2 years | Someone else | School nurse |

| Physical | >10 times | ||||

| 3 | 61 | Emotional | 3–5 times | Partner | Counsellor, social services |

| Physical | Someone else | ||||

| 4 | 36 | Physical | 1–2 times | Someone else | Psychologist, occupational health service |

| Sexual | 1–2 times | ||||

| 5 | 30 | Physical | 3–5 times | Someone else | Counsellor, psychiatric care |

| 6 | 63 | Emotional | >2 years | Partner | Physician, psychiatric care and emergency department |

| Physical | >10 times | Family member | |||

| 7 | 45 | Emotional | >2 years | Partner | Counsellor, social services |

| Physical | 3–5 times | Psychologist, private care | |||

| 8 | 37 | Emotional | >2 years | Someone else | School nurse |

| Physical | >10 times | Physician, primary care | |||

| 9 | 69 | Physical | 1–2 times | Family | Physician, emergency department and ocular department |

| 3–5 times | Someone else | ||||

| 10 | 52 | Physical | >10 times | Partner | Counsellors, social services |

| 11 | 63 | Emotional | >2 years | Family member | No one |

| Physical | >10 times | ||||

| 12 | 32 | Emotional | >2 years | Family member | Psychologist, private care |

| Physical | >10 times | Someone else | |||

| Declined participation | |||||

| 13 | 53 | Emotional | >2 years | Partner | Counsellor, psychiatric care |

| Sexual | 1–2 times | Someone else | |||

| 14 | 41 | Physical | 3–5 times | Someone else | Counsellor, nurse, psychiatric care and primary healthcare centre. |

| Sexual | >10 times | ||||

| 15 | 67 | Physical | 1–2 times | Someone else | Physician emergency department |

Though only one man had not told anyone about his experiences of victimisation, all of the men had experiences of not disclosing. They all had healthcare visits during which they had not told the professional about their experience.

We applied the logic of theoretical sampling, defined by Charmaz29 as seeking data to develop the emerging theoretical model and refine its categories. This was done by a constant modification of the interview guide and through specifically identifying whom to talk to next. In our study, the background characteristics presented in table 2 were used for this purpose, assuming and noticing that these properties mattered for how our theoretical model developed. After nine interviews, no new categories were created. Three more interviews were conducted, which stabilised and further refined the categories.

Interviews

The first author (JS) recruited informants by telephone and conducted all the interviews between November 2012 and January 2013. Beforehand, informants were sent an email about the main topic of the interview and why the study was conducted. The email was signed with the first author's name and profession (MD, PhD candidate). The interviews were conducted in Swedish and lasted between 20 min and 1 hour 38 min (median: 45 min). They were conducted either in an office (n=10) or a small conference room (n=2) at the university. Each informant was only interviewed once and only JS and the informant were present in the room. Member checking was not used. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each interview started with inviting the men to talk about their experiences of victimisation, and then the following interview questions were asked, followed by prompts, if needed.

Can you tell me about a situation where you talked to a healthcare provider about the violence you have been subjected to?

Have you ever been in a situation where you wanted to tell healthcare providers about your victimisation but chose not to do so? If so, what held you back?

In what kind of situations do you think it is desirable and/or important to talk to healthcare professionals about violence?

What advice would you give to healthcare professionals who wish to talk about experiences of being subjected to violence with their patients?

Many victims of violence choose not to tell medical professionals about their victimisation. Why do you think that is?

Analysis

The first author (JS) performed line-by-line coding after each interview in the manner described by Charmaz.29 A constant comparative analysis was used in which codes were compared to each other, within an interview and between interviews. As the next step, focused coding was used, whereby the most significant line-by-line codes were used to categorise and synthesise the data. This level of coding is on a more abstract and interpretive level and patterns within the data are traced. Throughout the coding processes, JS also wrote memos that included reflections and interpretations of the interviews.

JS is a female MD and was at the time of the interviews a PhD candidate. She had formal training but little practical experience with qualitative research. To ensure the quality of the study, analysis was triangulated between all authors. The second author (AJB) is a social scientist and has a PhD in medical sciences. He has conducted multiple grounded theory studies. The third author (KS) is a registered nurse and professor. She has a long experience with qualitative research in general and grounded theory in particular. KS and JB read all interviews to familiarise themselves with the data and also performed line-by-line coding of two of the interviews to ensure that all authors interpreted the data in a similar way. JS and JB performed focused coding individually where after they met to perform theoretical coding together, discussing how codes and categories were related to each other and could be interpreted and integrated into theoretical concepts. Subsequently, JS began to work with the theoretical concepts and revisited the early codes and memos while writing new memos. Finally, the theoretical model was evaluated for each man's individual process of disclosure.

Ethical considerations

It is possible that the interviews evoked negative feelings and unwanted recollections for the men. The men were therefore provided with the contact information of an independent therapist. Participation was voluntary, and the men could choose to stop the interview at any time. All of the men signed a written consent form. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board (registration number 2012/194-31).

Results

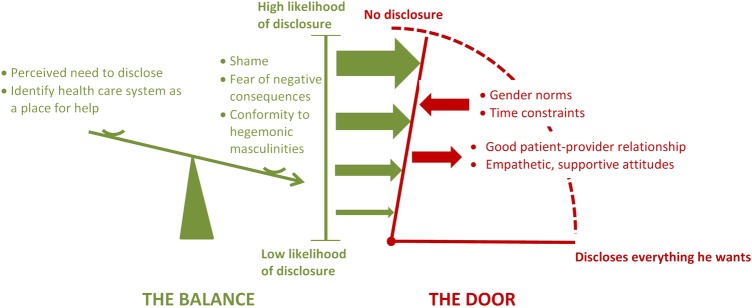

Disclosing experiences of being subjected to violence to healthcare professionals was found to be a dynamic, non-linear process that could be understood by using two theoretical concepts that were closely related and dependent on each other: the metaphors that we call ‘the balance’ and ‘the door’ (figure 1).

Figure 1.

An illustration of our theoretical model. ‘The balance’ illustrates that the men's likelihood of disclosing experiences of being subjected to interpersonal violence to healthcare professionals was dependent on a variety of factors balanced against one another. ‘The door’ illustrates the dynamics during the actual encounter, where the door's opening represents if how much and what the men disclose. The arrows in the model symbolise that the men's likelihood of disclosure translates to the force by which they try to open ‘the door’. The healthcare professionals had a strong influence on how much and what the men disclose.

‘The balance’ was used to illustrate that the likelihood of disclosure was dependent on a variety of factors balanced against one another. For example, men's conformity to hegemonic masculinity and feelings of shame related to victimisation could tip ‘the balance’ towards a low likelihood of disclosure, whereas a strong need for help could tip it towards a high likelihood of disclosure.

The metaphor called ‘the door’ illustrates the dynamics in play during the actual disclosure, where the door's opening represents if and how much the men disclosed. Healthcare professionals acted as doorkeepers and had a strong influence on the process of disclosure. For example, by acting empathic and building trust, the healthcare professionals opened ‘the door’. Contrary, time constraints and professionals gendered expectations, such as not acknowledging male victimisation or suffering, could be ways that healthcare professionals closed ‘the door’.

The male victims and the healthcare professionals were active in the process of disclosure. As illustrated in figure 1, the position of ‘the balance’ transformed into the force that the victim used to push ‘the door’ open. If ‘the balance’ was tipped towards a high likelihood of disclosure, the healthcare professional would only need to listen for disclosure to occur. If ‘the balance’ was tipped towards a low likelihood of disclosure, the healthcare professionals would need to take a more active role, build trust and ask questions. Also, even when ‘the balance’ shifted towards a high likelihood of disclosing victimisation to healthcare professionals, the men still had to come in contact with healthcare professionals. Some of the men sought help themselves; others received help to contact healthcare professionals from people in their vicinity. For others, life events unrelated to their victimisation triggered help-seeking.

Theoretical concept: ‘the balance’

Factors and feelings associated with the experience of victimisation

A sense of urgency to seek help and feeling ready to talk about one's victimisation were strong factors that tipped ‘the balance’ towards a high likelihood of disclosing victimisation, whereas a low perceived need for help tipped ‘the balance’ towards a low likelihood of disclosure. The men's perceived need to disclose was in part dependent on their current suffering, but also in part on their social networks and the support they could receive elsewhere. Experiences of violence were part of the men's life story, rather than isolated events. When the men experienced unrelated life difficulties, their need to disclose victimisation tended to increase.

For most of the interviewed men, shame was a major factor that tipped ‘the balance’ towards nondisclosure. One man who had been abused by his father during his childhood expressed his feelings of shame in the following way:

‘I didn't want anyone to know… […] I just wanted the lid to be put on. I found it so sensitive. Because really, nobody knew, nobody understood anything. Not my closest friends, nothing… I don't know; one feels so terribly ashamed to… yeah… shame, just like that’.

Experiences and fears in relation to the healthcare system

The men's previous experiences with, or beliefs about, the healthcare system had a strong influence on their likelihood of disclosing victimisation. Some men said that they did not recognise the healthcare system as a resource from which to seek help, except for physical injuries.

A fear of negative consequences for themselves or others as a result of disclosing victimisation tipped ‘the balance’ towards a low likelihood of disclosure. Some expressed a fear that they would not be believed and that their story could somehow be turned against them. In particular, this fear was articulated in relation to losing child custody rights when the perpetrator was a former female intimate partner. The fear of negative consequences could also involve the perpetrator; for example, one man said he did not want to tell anyone about his abusive father because he wanted to protect his father from the police or social authorities.

Some men expressed a lack of trust in confidentiality between patients and caregivers, which tipped ‘the balance’ towards a low likelihood of disclosure. They were worried that healthcare providers would repeat parts of their story to other people or that the physical space did not allow for privacy. In particular, men who lived in a small village were sometimes afraid that others would find out about their victimisation. One man had been subjected to violence by his female intimate partner and had previously worked at the hospital where he sought help. During the interview, he sighed and said:

‘Patient-provider confidentiality is all very well, but people talk a lot within the health care system’.

Masculinity

Conforming to hegemonic masculinity was a heavy weight tipping ‘the balance’ towards nondisclosure.

One expression of conformity to hegemonic masculinity was the reluctance to seek help, despite suffering in the aftermath of victimisation. When discussing why it took him several years to disclose his victimisation one man said:

‘As I said, it's kind of an honour thing. It's about keeping face […] A guy should not… he cannot cry [sighing], I mean a guy shouldn't, it's the way it is’.

Sometimes the men downplayed what had happened to them or their need for help. Some men had done this to the extent that they had a breakdown, but they still needed someone in their vicinity to make them seek professional help. In all such cases, the ‘helpers’ were women. One man had a breakdown at a party, and a female friend helped him contact a therapist. Another man sat drunk at home for a week until his aunt took him to the primary healthcare centre.

Some men said that it was easier to talk about victimisation with female healthcare professionals and some said that it is more difficult for men to talk about experiences of violence than it is for women, particularly concerning victimisation by an intimate partner. The men expressed that, because male intimate partner victimisation is not acknowledged by society as much as partner violence towards women, they felt that they were alone in their experience. Some feared—or had in fact experienced—not being believed or taken seriously by healthcare professionals. When one man, who had been subjected to violence by his female partner, was asked in the interview whether he had ever sustained physical injuries serious enough to require a visit the hospital, he replied as follows:

Yeah, biting. Well, she bit me here so that the skin came off. […] But then you were reluctant to go and talk about, go to… the hospital and say that… my partner has bitten me. You are reluctant to do that. Then you take a chance and sees if it becomes, eh… a blush or an infection or something, then you seek help. Because I believe that… […] I believe that it is even harder and more difficult if you are a man.

Theoretical concept: ‘the door’

The caring encounter

It was evident that the behaviour of the healthcare professional played a significant role in the men's disclosure of victimisation. A supportive, empathic attitude from a professional who truly listened opened ‘the door’ for disclosure. Although this confidence could be built in just one session for some, others required a long-term relationship for disclosure. It was also clear that the meeting with the healthcare professionals needed to be individually tailored. For some, an active professional was essential, that is, someone who was observant, asked questions and saw behind the front that the men had created.

Professionals' gender expectations

Some men had experiences of professionals who seemed to expect them to construct hegemonic masculinities. This was perhaps most evident in the story of one man who had been victimised by his female intimate partner. He had sustained a physical injury and told the story of his experiences at the emergency room. During the interview, he was asked whether he had told the healthcare professionals that it was his female intimate partner who had inflicted the injury.

Well, I did that a couple of times, but, but… eh… they laughed more or less. ‘Did you get beaten by a girl? Ha, Ha, can't you hit back?’ […] Yeah, yeah… It's the way it works. Men are not beaten up by women. It's only women who are beaten up by men.

The men said that they sometimes encountered a lack of compassion from healthcare professionals, which they interpreted to be because they were men. For example, physical violence from a peer can be linked to considerable psychological suffering, but such violence seemed to have been normalised by the healthcare professionals and the men were not expected to suffer beyond their broken bones. One man had been punched by a stranger on the street until he was unconscious, and the next morning, when he was still in his hospital room, the perpetrator unexpectedly was standing in front of him. He was again scared for his life.

When I think about it, the most horrible was that in the morning, when I woke up, the guy who had kicked me came. And they let him in. They didn't ask me, I mean, from my point of view, how I would feel when that guy came in and… yeah… […] That is what I thought. It's because I'm a guy. They would never have let in a… guy to [visit] a girl. They wouldn't have done that. It's like that; it's ignored. It's business as usual that… guys should just shake hands and move on and… like a darn robot.

Discussion

Principal finding

Disclosing victimisation to healthcare professionals was a complex process involving the men's own experiences of violence and life circumstances as well as the dynamics of the actual healthcare encounter. Many of the factors influencing our theoretical model resemble those identified in previous studies concerning female victims of intimate partner violence. Our study, however, extends previous research by including male victims of any kind of violence and emphasising the strong negative effects that adherence to stereotypical gender norms have on the process of disclosing. It is also emphasised that disclosure of victimisation cannot be considered as separate from other life circumstances.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is the first study to explore men's experiences of disclosing victimisation to healthcare professionals in Sweden. We chose to include men with experiences of different forms of violence from different kinds of perpetrators. Although this hindered us from identifying violence-specific processes of disclosing, we consider our approach a strength, because it did allow us to capture core features of disclosing for a wide range of victimisation, mirroring the diverse experiences that health professionals' encounter. Instead of eliciting nuances, we aimed to present a general model that can inform future healthcare interventions towards victims of violence. Looking for general features of disclosing also explains why saturation was reached after nine interviews, despite great variety in victimisation.

It is well known that many victims of violence are also perpetrators of violence.9 33–35 Keeping our focus on disclosing victimisation, we chose not to discuss perpetration of violence in the interviews. This might have affected the theoretical model, considering that it is possible that also being a perpetrator of violence is what keeps victims from disclosing. This is an important topic to address in further research.

Previous research has demonstrated that victimisation, help-seeking and disclosure are affected by ethnicity and sociocultural context.16 28 36 In our study, all but one of the men were born in Sweden. It is a limitation of this study that we were not able to consider how, for example, gender and ethnicity are simultaneously constructed and affect the process of disclosure. Additionally, if the study had been conducted in another country, other factors would probably have affected ‘the balance’ and ‘the door’. For example, because healthcare is publicly financed in Sweden, insurance coverage is not an obstacle for help-seeking, but this may be the case in other countries.11 37

The research interview is a social interaction in a specific setting.38 JS is an MD who wishes to improve the healthcare system's response to victims of violence and as such she may have asked for and received responses in that particular direction, but in which ways was not evident in the interviews. JS was not involved in the informants' care and it was clearly stated that their participation in the study would not affect their future care. Previously, gender has been suggested to be a resource and a delimiting factor within the qualitative interview.39 By taking on the role of an empathic listener, the interviewer constructed traditional femininity and a few of the interviewed men expressed that they could not have disclosed their experiences if the researcher had been a man. Similar experiences have been reported by other female researchers interviewing male informants.40

Our results in relation to other studies

Shame caused ‘the balance’ to shift towards a low likelihood of disclosure. The importance of shame in relation to help-seeking has been noted before, and shame is a well-known component in experiences of different kinds of violence.15 16 41 42 Several of the factors that influenced ‘the balance’ in our study were also found in studies of help-seeking behaviours among female victims. For example, not knowing where to go for help, fear of negative consequences and not trusting in maintenance of confidentiality have previously been identified as obstacles to help-seeking among female victims of intimate partner violence.7 16 42 Additionally, in accordance with previous studies, identifying the need to seek help and feeling ready to disclose victimisation are central components that tip ‘the balance’ towards a high likelihood of disclosure.16 42

As in previous studies of female victims of intimate partner violence, we found that a patient–provider relationship characterised by trust, compassion and confidentiality was an important factor that opened ‘the door’ and thereby facilitated disclosure. Other important factors recognised in previous studies are the amount of time available for discussion with the professional and an individually tailored response to disclosure.10 23 37 42

Previously, men who endorse views that men should be self-sufficient, be strong and control their emotions have been found to be less prone to seeking psychological help.28 In the current study, some men also expressed views that they should handle the problem themselves, an attitude also identified as a barrier to help-seeking among female victims of intimate partner violence.7 15 For men, this is in line with norms of hegemonic masculinity, a concept we used as an interpretative tool. While these findings also can be interpreted as attitudes related to being a victim of violence, they also elicit an intimate connection between victimisation, gender norms and help-seeking. So-called self-stigma has been found to be a mediating factor between dominant masculinity and attitudes towards seeking help. Self-stigma refers to internalised negative views found in society towards help-seeking, for example, believing that one is inferior or weak for seeking psychological help.28 The men's reluctance to seek help was mirrored by the experience of some of them that healthcare professionals did not acknowledge their psychological suffering because they were men. This was most explicit for those who had experiences of violence perpetrated by a female intimate partner. Those men expressed worries about, or had direct experience of, not being taken seriously when seeking help. This is in line with previous research on help-seeking among male victims of intimate partner violence in the USA13 as well as in Sweden.34

Some of the men got in contact with healthcare professionals through the help of others. Interestingly, all the ‘helpers’ were women. Additionally, some men said that they had disclosed victimisation only because the healthcare provider was a woman. Why did the men turn to women for help? It could be a consequence of constructions of femininity: women are seen as more caring and easier to talk to than men, a view articulated by some of the men. But equally interesting, why did the men not turn to other men for help? The hierarchy between different masculinities and their relation to the constructs of femininity is complex, but it presumes the subordination of non-hegemonic masculinities.26 43 For example, within male homosocial groups, emotional detachment is associated with being masculine, whereas discussing feelings is associated with femininity. The latter is considered inappropriate for the male homosocial group and may lead to exclusion.44 Exposing oneself as a victim of violence and thereby taking a subordinate position could be a threat to the men's sense of masculinity. In addition, discussing emotions and vulnerability with another man can be stigmatising in itself. This could explain why disclosing victimisation to other men might be even more difficult than disclosing to women.

Clinical implications

In this study, talking about victimisation was referred to as an unmet need, and subsequent feelings of relief were described. However, the route to disclosure was difficult for many; several of the men needed help in contacting the healthcare system and/or needed healthcare professionals to be alert and ask questions. Previous studies have shown that female victims of intimate partner violence find it difficult to spontaneously disclose victimisation, but are often positive about healthcare providers asking questions.10 37 42 Although not all victims of violence want to talk to healthcare professionals about their victimisation, disclosure needs to be facilitated for those who do. When victims disclose, this gives healthcare professionals an opportunity to help them and to conduct relevant referrals, and unnecessary investigations can be avoided.

Some efforts for improving healthcare response to male victimisation have been made.45 However, more education for professionals concerning male victimisation is warranted, so that professionals' stereotypically gendered expectations can be reduced within the healthcare system.

Much research concerning the healthcare response to intimate partner violence tends to focus on evaluating screening tools and screening methods (eg, computer based vs face to face).23 46 47 In future research, concerning interventions to improve healthcare for victims of violence, the complexity of the disclosing process demonstrated in the current study, as well as previous studies concerning help-seeking, needs to be better addressed. For example, a lack of trust in patient–provider confidentiality was expressed in this study, as in previous studies.10 37 42 It would be interesting to study if measures to ensure confidentiality, including improvements in the organisation of the physical room, would affect disclosure rates.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS and KS prepared the interview guide. JS performed all interviews, transcribed 10 interviews and performed coding of all interviews. AJB read the transcripts of all interviews and performed line-by-line coding as well as participated in theoretical coding. KS read all interviews and performed line-by-line coding of two of the interviews. JS prepared the first draft of the manuscript. AJB and KS critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Region Östergötland, Sweden (grant numbers LIO-340221 and LIO-514621).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethical Review Board, Linköping.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymised transcripts of the original interviews (in Swedish) can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med 2002;23:260–8. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ace) study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romito P, Grassi M. Does violence affect one gender more than the other? The mental health impact of violence among male and female university students. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:1222–34. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott-Storey K. Cumulative abuse: do things add up? An evaluation of the conceptualization, operationalization, and methodological approaches in the study of the phenomenon of cumulative abuse. Trauma Violence Abuse 2011;12:135–50. 10.1177/1524838011404253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hines DA, Douglas EM. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in men who sustain intimate partner violence: a study of helpseeking and community samples. Psychol Men Masc 2011;12:112–27. 10.1037/a0022983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NCK. Våld och hälsa. En befolkningsundersökning om kvinnors och mäns våldsutsatthet samt kopplingen till hälsa, nck-rapport 2014:1. Uppsala: The National Centre for Knowledge on Men's Violence Against Women [Nationellt Centrum för Kvinnofrid, NCK], 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postmus JL, Severson M, Berry M et al. Women's experiences of violence and seeking help. Violence Against Women 2009;15:852–68. 10.1177/1077801209334445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmons J, Wijma B, Swahnberg K. Associations and experiences observed for family and nonfamily forms of violent behavior in different relational contexts among Swedish men and women. Violence Vict 2014;29:152–70. 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamby S, Grych J. The web of violence. In: Johnson RJ, ed.. Exploring connections among different forms of interpersonal violence and abuse. New York: Springer, 2013:9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feder GS, Hutson M, Ramsay J et al. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:22–37. 10.1001/archinte.166.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ullman SE. Mental health services seeking in sexual assault victims. Women Ther 2007;30:61–84. 10.1300/J015v30n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns 2005;59:141–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas EM, Hines DA. The helpseeking experiences of men who sustain intimate partner violence: an overlooked population and implications for practice. J Fam Violence 2011;26:473–85. 10.1007/s10896-011-9382-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreiber V, Maercker A, Renneberg B. Social influences on mental health help-seeking after interpersonal traumatization: a qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health 2010;10:634 10.1186/1471-2458-10-634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber V, Renneberg B, Maercker A. Seeking psychosocial care after interpersonal violence: an integrative model. Violence Vict 2009;24:322–36. 10.1891/0886-6708.24.3.322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P et al. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. Am J Community Psych 2005;36:71–84. 10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KL. Theorizing gender in intimate partner violence reserach. Sex Roles 2005;52:853–65. 10.1007/s11199-005-4204-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimmel MS. Gender symmetry in domestic violence: a substantive and methodological research review. Violence Against Women 2002;8:1332–63. 10.1177/107780102237407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hines DA, Douglas EM. A closer look at men who sustain intimate terrorism by women. Partner Abuse 2010;1:286–313. 10.1891/1946-6560.1.3.286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hines DA, Douglas EM. Intimate terrorism by women towards men: does it exist? J Aggress Confl Peace Res 2010;2:36–56. 10.5042/jacpr.2010.0335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson MP. Conflict and control: gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women 2006;12:1003–18. 10.1177/1077801206293328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women's and men's experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1011–18. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapur NA, Windish DM. Optimal methods to screen men and women for intimate partner violence: results from an internal medicine residency continuity clinic. J Interpers Violence 2011;26:2335–52. 10.1177/0886260510383034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimberg LS. Addressing intimate partner violence with male patients: a review and introduction of pilot guidelines. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:2071–8. 10.1007/s11606-008-0755-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linnarsson JR, Benzein E, Årestedt K et al. Preparedness to care for victims of violence and their families in emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2013;30:198–201. 10.1136/emermed-2012-201127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connell RW. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G. ‘It's caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: men's accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:503–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogel DL, Heimerdinger-Edwards SR, Hammer JH et al. ‘Boys don't cry’: examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:368–82. 10.1037/a0023688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE Publications, 2006:1–148. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1967/1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swahnberg K. Norvold Abuse Questionnaire for men (m-NorAQ): validation of new measures of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and abuse in health care in male patients. Gend Med 2011;8:69–79. 10.1016/j.genm.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swahnberg K, Wijma B. The NorVold Abuse Questionnaire (NorAQ): validation of new measures of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and abuse in the health care system among women. Eur J Public Health 2003;13:361–6. 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodin EM, Sotskova A, O'Leary KD. Intimate partner violence assessment in an historical context: divergent approaches and opportunities for progress. Sex Roles 2013;69:120–30. 10.1007/s11199-013-0294-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nybergh L, Enander V, Krantz G. Theoretical considerations on men's experiences of intimate partner violence: an interview-based study. J Fam Violence 2016;31:191–202. 10.1007/s10896-015-9785-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hester M, Ferrari G, Jones SK et al. Occurrence and impact of negative behaviour, including domestic violence and abuse, in men attending UK primary care health clinics: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007141 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alaggia R, Regehr C, Jenney A. Risky business: an ecological analysis of intimate partner violence disclosure. Res Social Work Pract 2012;22:301–12. 10.1177/1049731511425503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, Bauer HM. Breaking the silence. Battered women's perspectives on medical care. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:153–8. 10.1001/archfami.5.3.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies D, Dodd J. Qualitative research and the question of rigor. Qual Health Res 2002;12:279–89. 10.1177/104973230201200211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broom A, Hand K, Tovey P. The role of gender, environment and individual biography in shaping qualitative interview data. Int J Soc Res Method 2009;12:51–65. 10.1080/13645570701606028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arendell T. Reflections on the researcher-researched relationship: a woman interviewing men. Qual Sociol 1997;20:341–68. 10.1023/A:1024727316052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fanslow JL, Robinson EM. Help-seeking behaviors and reasons for help seeking reported by a representative sample of women victims of intimate partner violence in New Zealand. J Interpers Violence 2010;25:929–51. 10.1177/0886260509336963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hathaway JE, Willis G, Zimmer B. Listening to survivors’ voices—addressing partner abuse in the health care setting. Violence Against Women 2002;8:687–719. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: rethinking the concept. Gender Soc 2005;19:829–59. 10.1177/0891243205278639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bird SR. Welcome to the men's club: homosociality and the maintenance of hegemonic masculinity. Gender Soc 1996;10:120–32. 10.1177/089124396010002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson E, Jones SK, Ferrari G et al. Health professionals responding to men for safety (HERMES): feasibility of a general practice training intervention to improve the response to male patients who have experienced or perpetrated domestic violence and abuse. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2015;16:281–8. 10.1017/S1463423614000358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E et al. Screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;302:493–501. 10.1001/jama.2009.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mills TJ, Avegno JL, Haydel MJ. Male victims of partner violence: prevalence and accuracy of screening tools. J Emerg Med 2006;31:447–52. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]