Abstract

Introduction

Interventions to improve child diet are recommended as dietary patterns developed in childhood track into adulthood and influence the risk of chronic disease. For child health, childcare services are required to provide foods to children consistent with nutrition guidelines. Research suggests that foods and beverages provided by services to children are often inconsistent with nutrition guidelines. The primary aim of this study is to assess, relative to a usual care control group, the effectiveness of a multistrategy childcare-based intervention in improving compliance with nutrition guidelines in long day care services.

Methods and analysis

The study will employ a parallel group randomised controlled trial design. A sample of 58 long day care services that provide all meals (typically includes 1 main and 2 mid-meals) to children while they are in care, in the Hunter New England region of New South Wales, Australia, will be randomly allocated to a 6-month intervention to support implementation of nutrition guidelines or a usual care control group in a 1:1 ratio. The intervention was designed to overcome barriers to the implementation of nutrition guidelines assessed using the theoretical domains framework. Intervention strategies will include the provision of staff training and resources, audit and feedback, ongoing support and securing executive support. The primary outcome of the trial will be the change in the proportion of long day care services that have a 2-week menu compliant with childcare nutrition guidelines, measured by comprehensive menu assessments. As a secondary outcome, child dietary intake while in care will also be assessed. To assess the effectiveness of the intervention, the measures will be undertaken at baseline and ∼6 months postbaseline.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee. Study findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publications.

Keywords: Nutrition guidelines, Obesity prevention, Healthy eating, Childcare, Implementation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study incorporates random allocation of long day care services and blinding of the dietitian assessing compliance to nutrition guidelines.

The intervention is based on a theory-informed systematic process to target barriers and enablers identified by the childcare setting.

The intervention is conducted in the Hunter New England region of New South Wales and findings may not generalise nationally.

Multiple observation periods may improve the validity of the assessment on usual child food intake.

Introduction

Internationally, dietary risk factors are a primary cause of death and disability. In 2010, the Global Burden of Disease study reported that over 11 million deaths worldwide were due to dietary risk factors alone.1 Of these deaths, 4.9 million were linked to low fruit intake, 1.7 million to low vegetable intake and 3.1 million to a high sodium intake.1 In Australia, ∼23% of total mortality and 11% of disability-adjusted life years during 2010 were attributable to dietary risk factors.1

Dietary patterns and food preferences developed in childhood track into adulthood and influence the risk of future chronic disease.2 Developing healthy eating patterns in childhood is therefore recommended by the WHO and governments internationally as a key chronic disease prevention strategy.3 Childcare services represent an opportune setting to improve the dietary intake of children as they provide access to a large number of children for prolonged periods of time at a critical stage of development.4 Further, systematic review evidence suggests that improving the childcare nutrition environment can improve dietary and health outcomes for children.4

It is recommended that childcare services provide foods to children consistent with dietary guidelines.5 6 International research, however, suggests that foods and beverages provided by services to children are often inconsistent with guideline recommendations. A study conducted in the UK audited 118 nursery menus and found that none adhered to nutrition guidelines.7 Similarly in Australia, 46 long day care service menus were reviewed and none provided adequate serves of vegetables consistent with the guidelines.8 Childcare services report a number of barriers to complying with nutrition guidelines, including limited professional development opportunities, lack of practical resources, lack of time and inadequate support from management and colleagues.9 10

Childcare services in Australia do not receive a subsidy from the government for the provision of meals that comply with the nutrition guidelines. For childcare services in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, the current nutrition recommendations are outlined in the Caring for Children resource which has been publicly available online since October 2014.11 The resource was developed by the NSW Ministry of Health to assist childcare services to provide food that is consistent with the sector-specific nutrition guidelines. The content is based on experience in the field and consultation with childcare service representatives and outlines best practice guidelines on healthy eating and nutrition for the childcare setting. The resource provides guidance on menu planning and the number of serves of foods that need to be provided on a service menu to be compliant with guidelines. In NSW assessment and compliance officers, who regulate service accreditation, use the Caring for Children resource as a benchmark for determining if services meet accreditation standards in relation to the provision of healthy food and drinks to children while in care.

If the health benefits of nutrition guidelines for the childcare sector are to be realised, interventions to support services to overcome barriers to routine implementation are required. The few trials that have been conducted to assess how to best support the implementation of nutrition guidelines in childcare services report mixed results on implementation outcomes, providing a limited evidence base for efforts to improve implementation of nutrition guidelines and practices in this setting.12–20 In addition, the majority of these trials do not explicitly report applying an implementation framework to guide intervention development and strategy selection.13 19 20 Nonetheless, existing findings from these trials suggest that strategies such as resource provision, performance monitoring and feedback, ongoing support and professional development opportunities for service cooks and service managers may be effective in changing food provision in line with nutrition guidelines.12 15–21 Furthermore, it is suggested that strategies to increase childcare staff awareness of the nutrition guidelines may also be effective in improving compliance with nutrition guidelines in the setting.22

While a number of non-randomised trials have assessed the impact of changing food provision in line with nutrition guidelines on child dietary intake, to the best of our knowledge no randomised trials of such interventions have been undertaken.14 16–18 Such trials are required to better assess the health impact of such implementation strategies on child health.

Methods and analysis

Study aim

Given the limitations of the existing evidence base, the primary aim of the study is to assess, relative to usual care, the effectiveness of a multistrategy childcare-based intervention in improving the compliance with nutrition guidelines in long day care services. As a secondary aim, the impact on child dietary intake during the hours attending care will also be assessed.

Study design

The study will employ a randomised controlled trial design. Fifty-eight long day care services will be allocated to receive either the multicomponent intervention to support nutrition guideline implementation or a usual care control group. Service compliance with nutrition guidelines regarding food provision will be assessed by menu assessments undertaken by a dietitian blind to group allocation at baseline and at ∼6 months following baseline data collection. Child dietary intake will be assessed by aggregate plate waste measures and educator-completed child food intake questionnaires.

Setting

The study will take place across one local health district of NSW, Australia (Hunter New England). The Australian Statistical Geography Standard describes the region as encompassing non-metropolitan ‘major cities’ and ‘inner regional’ areas.23 Over 840 000 people reside in the area, of which ∼33 300 are aged 3–5 years.24 There are currently 368 childcare services in the study region, of which 107 are long day care services which prepare and provide food onsite to children while in care. A subsample of 58 services will be invited to participate in this trial.

Sample

To be eligible to participate in the trial, long day care services must prepare and provide one main meal and two mid-meals to children while they are in care, and be open for at least 8 hours per day. Services that do not prepare and provide meals to children onsite or do not have a cook with some responsibility for menu planning will be excluded from the study. Further, services catering exclusively for children requiring specialist care will be excluded, as will mobile preschools and family day care centres given the different operational characteristics, and therefore intervention requirements of these services relative to permanent centre-based care services.

Recruitment procedures

A list of all long day care services in the study region will be supplied by the NSW Ministry of Health and serve as the sampling frame. Service managers will be mailed recruitment letters ∼1 week prior to recruitment, informing them of the study and inviting participation. A research assistant will contact services to confirm eligibility and invite participation. The order at which services will be approached to participate in the study will be randomised using a random number function in Microsoft Excel. Consent will be obtained through the service manager via the return of the service's current 2-week menu. Study recruitment will continue until the required sample is achieved. To assess secondary outcome measures, a nested evaluation will be undertaken in a randomly selected subsample of 34 participating services located in the Hunter region. For such services, managers will also be asked if they consent to participate in a site visit to assess child dietary intake via plate waste. Services will be asked to return consent forms if they choose to participate in the site visits. To maximise study participation, a dedicated recruitment coordinator will make multiple attempts to contact services at times convenient to the centre.17 25 26 The research team have extensive experience in the childcare setting and achieving consent rates of >80% in previous trials undertaken.17 27

To assess selective non-participation bias, the coordinator will also monitor participation rates and document characteristics of consenting and non-consenting services.28

Random allocation of childcare services

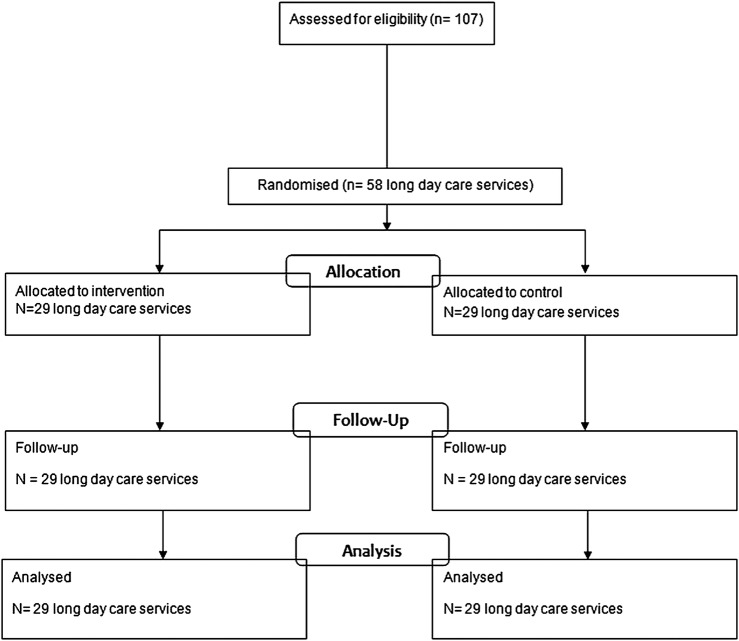

Consenting childcare services will be randomly allocated to an intervention or control group in a 1:1 ratio via block randomisation using a random number function in SAS statistical software (see figure 1). Block size will range between 2 and 6. Allocation of services will be undertaken by an experienced research assistant. Outcome data collectors will be blinded; however, long day care service staff will be aware of their group allocation.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram estimating the progress of long day care services through the trial.

Intervention

Implementation intervention

The multicomponent intervention was designed by an expert advisory group of health promotion practitioners, implementation scientists, dietitians and behavioural scientists in consultation with childcare service cooks and service managers. The intervention strategy selection is based on a theoretical framework and previous research evidence in the childcare setting.26 28–30

Application of a theoretical framework

The theoretical domains framework was the basis for intervention development.31 32 The theoretical domains framework is an integrative theoretical framework developed for behavioural research and incorporates 33 theories of behaviour change. The framework includes the following health behaviour change domains: knowledge; skills; social/professional role and identity; beliefs about capabilities; optimism; beliefs about consequences; reinforcement; intentions; goals; memory, attention and decision processes; environmental context and resources; social influences; behavioural regulation.33 The framework has previously been used to design effective interventions to improve guideline implementation in clinical settings.29 33 34 Further information about the domain definitions and constructs is reported by Cane et al.33 The theoretical domains framework was chosen by the research team as it has been empirically validated, successfully applied in numerous healthcare settings and covers ∼95% of constructs targeting behaviour change.34–38

The theoretical domains framework was used to assess the potential behavioural determinants of the implementation of nutrition guidelines in childcare services, and inform selection of intervention strategies to influence these.32 Specifically, literature reviews of previous implementation interventions targeting food provision in childcare and semistructured interviews with service cooks (n=7) using a modified theoretical domains framework questionnaire were undertaken, to identify the relevant domains in the framework that may influence (enable or impede) guideline implementation.29 39 The findings of the interviews were supplemented with on-site observations of food service practices and menu planning processes. On the basis of findings of the literature review, the interviews and the observations, a matrix developed by Michie et al31 was applied to map potential behaviour change techniques (implementation strategies) to the relevant theoretical domains (see table 1 for more detail). The implementation strategies to include in the intervention were selected on the basis of the mapping process and evidence of effect in changing behaviours; with consideration of contextual factors, programme resources and following further consultation with health promotion practitioners, childcare service managers and service cooks.31

Table 1.

Identified domains from quantitative and qualitative interviews, intervention content and delivery of intervention strategies

| Identified domain | Intervention content | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | The menu planning workshop will attempt to address the service managers and cooks awareness of the sector specific nutrition guidelines, the AGHE food groups and the daily recommended serves per child to be provided while in care.5 | The menu planning workshop |

| The menu planning workshop will introduce the Caring for Children resource, which outlines the sector-specific nutrition guidelines. Participating services will also be provided with menu planning tools and checklists, recipe ideas, budgeting factsheets and serve size posters during the workshop. | Printed or electronic resources | |

| Post attending the menu planning workshop services will receive two face-to-face service visits (duration 1–2 hours) with a support officer at their service on site, which will also target specific knowledge gaps regarding application of the guidelines and provide clarification about any information about the sector-specific nutrition guidelines that the service cook or manager were uncertain about. | Service visits | |

| Skills | During the menu planning workshop the service cook and service manager will be taught step by step how to plan a service menu that is compliant with the nutrition guidelines using the menu planning checklist within the Caring for Children resource. Each service will be asked to bring their current service menu to the training and as part of the workshop will review the menu items for one full day of their menu. Activities such as serve size calculations and recipe modification exercises will assist to develop the individual menu planning skills of the service cooks and service managers. In addition, small group discussions during the workshop will provide opportunities for services to share ideas, problem solve and practise menu planning processes together. | Menu planning workshop |

| The follow-up support contacts will provide additional opportunities for the service cook and manager to practice menu planning skills with their allocated support officer and receive immediate feedback and guidance to ensure menu compliance. | Follow-up support contacts | |

| Environmental context and resources | Services will be encouraged to adapt the service environment to be more supportive of the implementation of the nutrition guidelines. Services will be asked to display the nutrition guidelines and serve size posters in highly visible areas in the kitchen and to store provided resources at easily accessible areas. | Follow-up support contacts |

| Printed resources | ||

| Action planning | At the menu planning workshop, the service cook and service manager will set joint goals and action plans, using a goal setting template, to work towards menu compliance based on their completed review of one full day of the service menu. Services will be encouraged to begin developing SMART goals and indicate who is responsible to achieve each goal. A copy of the developed goals and action plans will be collected at the end of the workshop by each service's allocated support officer. | Menu planning workshop |

| During the follow-up contacts support officers will review the goals and actions plans of each service and use quality improvement principles encouraging service managers and cooks to identify problems, set new goals and implement action plans to facilitate services progression towards having a 2-week menu that is compliant with nutrition guidelines. | Follow-up contact | |

| Professional identity | The service cooks and service managers are to determine clear roles and responsibilities for the implementation of nutrition guidelines, as part of their goals and action plans, during the menu planning workshop. | Menu planning workshop |

| The MOU signed by the service cook and service manager during the initial follow-up service visit will recommend that the service manager be supportive of the implementation of the nutrition guidelines and communicate feedback directly to the service cook. | Follow-up support | |

| Service managers will be encouraged to update the service nutrition policy and the service cook position description to reflect the defined roles. | Securing executive support | |

| Beliefs about consequences (reinforcement) | The intervention will attempt to strengthen the relationship and communication between the service cook and service manager.49 The service manager will be encouraged to provide feedback to the cook throughout the intervention, as detailed in the signed MOU. Both the service manager and service cook will attend the support officer service visits, where they will together discuss the services progress towards compliance with the nutrition guidelines. | Follow-up support |

| A communication tool developed for the intervention will be provided to the services by their allocated support officer during the first follow-up contact. The communication tool is designed for the service cook and service manager to provide clear feedback about the service menu between each another and as a monitoring tool to document the steps undertaken by the respective parties. | Printed resources | |

| Social influences | The newsletters distributed throughout the study period will relay key messages, provide further meal and snack ideas for inclusion on the menu and highlight case studies from services that have made significant improvements to their service menu. Highlighting achievements of other intervention services can act as an external influencer to progress services towards having a 2-week menu that is compliant with nutrition guidelines. | Printed materials |

AGHE, Australian Guide to Healthy Eating; MOU, memorandum of understanding; SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, appropriate timeframe.

Intervention strategies

On the basis of the above process, a 6-month intervention to facilitate childcare service implementation of nutrition guidelines will be delivered to long day care centres. The intervention will target childcare service managers and service cooks given their primary role in the menu planning and food preparation process. Specifically, the intervention will consist of the strategies listed below. Further detail about the content of each strategy and how each strategy addresses the identified domains is given in table 1.

Provision of staff training

A 1-day face-to-face menu planning workshop will be provided to service managers and cooks to improve staff knowledge and skills in the application of nutrition guidelines to childcare food service. The workshop will incorporate both didactic and interactive components including small group discussions, case studies, facilitator feedback and opportunities to practise new skills.40–43 Experienced implementation support staff and dietitians will facilitate the workshop.

Provision of resources

All intervention services will receive a resource pack to support the implementation of nutrition guidelines which includes the Caring for Children resource, menu planning checklists, recipe ideas and budgeting fact sheets. Resources to support guideline implementation were selected on the sector barriers as identified in literature reviews and expressed by service cooks during the semistructured theoretical domains framework interviews.9 10 44

Audit and feedback

Intervention service menus will be audited by a dietitian and feedback provided at two time points. The first menu audit and feedback will use baseline data and be provided at the start of the intervention and the second will be mid-intervention. Intervention service cooks and service managers will receive written (email) and verbal (service visit) feedback following each menu assessment via their implementation support officer.45

Ongoing support

Intervention services will be allocated an implementation support officer to provide expert advice and assistance to facilitate guideline implementation. Each intervention service will receive two face-to-face contacts, following the menu planning workshop. Support contacts will be provided to service managers and cooks. Two newsletters will also be distributed to intervention services during the intervention period.46 47

Securing executive support

The implementation support officer, the service manager and cook will sign a memorandum of understanding outlining each party's responsibilities in working to improve food service. Service managers will be asked to communicate support and endorsement of adhering to nutrition guidelines to other staff and update the service nutrition policy accordingly (if required).48

Intervention quality assurance and monitoring

The delivery of the intervention will be managed by an experienced health promotion manager, who will provide the implementation support staff and dietitians with 1-day training to ensure that they are equipped with the skills and knowledge required to deliver the intervention. The training will cover communication skills, role plays, case study discussions, and data collection and documentation processes.

The intervention support staff will participate in fortnightly group meetings, facilitated by the health promotion manager, to ensure standardised intervention delivery, facilitate staff learning, identify intervention delivery problems, problem-solve and agree on standard responses to problems or service queries. Intervention delivery records will be maintained by implementation support staff. These records will be monitored to ensure that the intervention is delivered as per protocol. Deviations in protocol will be documented and addressed by the health promotion manager.

Control group

Services randomised to the control group will receive usual care and be posted a hard copy of the Caring for Children resource. The control services will not receive any other intervention support from the research team.

Measures

Service cook demographics and menu planning practices

Service cooks will be asked to complete a mailed pen and paper questionnaire at baseline and follow-up. The questionnaire will collect service cook demographic data (including education level, years employed as a service cook, age, weekly hours worked) as well as information about the current processes that relate to the planning of menus in their service and the provision of healthy foods. Items to assess how frequently the service menu is reviewed, how feedback is incorporated during a menu review and the hours typically taken to plan a service menu were adapted from items previously used in a state-based survey of childcare service providers conducted by the research team.

Childcare service operational characteristics, nutrition environment and menu planning practices

Childcare service operational and nutrition environment characteristics will be collected by a pen and paper questionnaire completed by the service manager at baseline and at follow-up. Childcare service operational characteristics will include the hours of operation and the total number of children who are enrolled at the service, the number that attend each day and the total number of staff. The items used to assess service characteristics have been used in other Australian surveys of childcare services conducted by the research team.50 The nutrition environment of services will be assessed using items validated in a previous sample of 42 Australian childcare services and included in the service manager questionnaire.27 51 The nutrition environment items include assessment of a nutrition policy and the role modelling behaviour of staff during meal times.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Compliance with nutrition guidelines

The primary outcome of the trial is the change in proportion of services with a 2-week menu that is compliant with the nutrition guidelines. Compliance will be assessed via a comprehensive menu assessment undertaken by a dietitian in accordance with best practice protocols for menu assessment undertaken at baseline and follow-up.52 Consistent with guideline recommendations, a compliant menu will be defined as one that provides 50% of the recommended daily serves of each of the Australian Dietary Guidelines five food groups ((1) vegetables and legumes/beans; (2) fruit; (3) wholegrain cereal foods and breads; (4) lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, seeds and legumes; (5) milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives) for children aged 2–5 years who attend each day.11 A comparison of plate waste measures and menu audits (unpublished) conducted by the research team found a 96% agreement in number of food groups provided among 84 meals, supporting the utility of menu assessments to assess overall guideline compliance. The recommended serve sizes are outlined in the Caring for Children resource and are based on the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE) recommendations. Table 2 shows the recommended number of serves to be provided on a childcare service menu consistent with childcare nutrition guidelines.

Table 2.

Recommended daily serves of food groups to be provided to children aged 2–5 years who attend care for 8 or more hours

| Food group | Recommended daily serves to provide for 8 or more hours of care (2–5 years old) |

|---|---|

| Vegetables and legumes/beans | 2 |

| Fruit | 1 |

| Wholegrain cereal foods and breads | 2 |

| Lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, seeds and legumes | 0.75 |

| Milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives | 1 |

Source: Caring for Children 2014 resource.11

Services will be asked to provide a copy of their current 2-week menu to the research team. An independent dietitian, blind to group allocation, will review menus and calculate serves of food groups provided per child per day, based on the AGHE food groups. For menu assessment, the food items on the menu will be classified into their appropriate food group and the total of each food group summed to generate the number of serves for each food group. If insufficient information is provided to enable food group classification, the dietitian will contact service cooks for additional information via a telephone or face-to-face visit. The dietitian will determine compliance with the nutrition guidelines based on the calculations of serves of each food group provided per child per day.

Compliance with nutrition guidelines for individual AGHE food groups

The change in proportion of services which comply with the nutrition guidelines for the individual food groups ((1) vegetables and legumes/beans; (2) fruit; (3) wholegrain cereal foods and breads; (4) lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, seeds and legumes; (5) milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives) and ‘discretionary’ foods will also be compared between the intervention and control group. ‘Discretionary’ foods are defined as those which are high in kilojoules, saturated fat, added sugars and added salt.11 Examples include cakes, sweet biscuits, chocolate, confectionery, crisps, pastries, commercially fried foods and high salt savoury biscuits.11 Discretionary foods are not recommended for provision in childcare services as outlined in the Caring for Children resource.11

Secondary outcomes

Theoretical domains framework constructs

Postintervention between-group differences in the theoretical domains framework constructs targeted by the intervention will be assessed as a process measures part of the cook's pen and paper questionnaire.

Food group consumption

Child food group consumption is measured on two levels—service level via aggregate plate waste measures and an individual level via educator-completed usual food intake questionnaires.

Service-level child food group serves consumption

The secondary trial outcome will be the grams of food consumed at the service per day for each of the core food groups and the ‘discretionary’ foods. The data will be collected in a subsample of 34 services. Plate waste methods will be used to obtain aggregate serves of food groups consumed by children while in care. Aggregated plate waste has been reported to be a valid method of assessing food intake at the group level and has been previously used in studies assessing the food intake of children in the school setting.53 Plate waste will be collected for one main meal and two mid-meals, at baseline and follow-up, during a full day data collection site visits. Two trained research assistants will undertake the plate waste measurements for each service. Data collection and assessment procedures will be based on those previously reported in the literature and will include the following:

Research assistants will collect the written menu and additional information including recipes from the service cook, for the day of data collection.

Once the food is prepared and cooked, prior to being served, the food items will be separated into their respective food groups based on the AGHE and the total mass of each food group will be weighed, to the nearest 0.1 g, using a digital scale (Nuweigh JAC838). Any liquids will be measured to the nearest millilitre. Mixed meals (those which include a combination of food groups) will be weighed as a total mass and the proportion of each food group contributing to the total mass will be determined from the recipe information collected from the service cook.

To measure waste, a number of tubs, dependent on the services menu items, will be provided to collect leftover food items. The tubs will be labelled with the AGHE food groups or mixed meals items included on the service menu. They will also be provided and labelled for any liquids; each liquid type will be poured into a separate waste tub. Leftover food items (including any food items found on the floor) will be similarly separated into food groups, placed in labelled waste tubs and weighed to determine the leftover mass. Mixed meals will again be weighed as a total mass. The research assistants will be responsible for grouping the leftover food items. When food items become mixed through the process of serving and/or eating and the food items are unable to be weighed separately postserving then they will be treated as a mixed food and serving sizes attributed on the basis of the combined food groups, determined from the recipe provided by the service cook.

The research team will subtract the leftover weight of each food group from the initial weights, providing the total weight of each food group consumed by the children.

The steps outlined above will be repeated for each meal within the 8 hours of care (typically two mid-meals and one main meal).

The research assistants will be trained in safe food handling practices and wear gloves at all times to address occupational health and safety concerns. The data collection service visits will be scheduled at a time convenient for the service cook and the measurements will be conducted to cause minimal disruption to the service cooks daily practices.

Usual child consumption of food group serves while in care

A further secondary outcome measure will be the usual serves of food, from each food group (as well as ‘discretionary’ foods) consumed by individual children attending each service. This will be measured in the same subsample of 34 services by childcare service educator-completed questionnaires at baseline and at follow-up. The food intake questionnaire was developed specifically for this intervention and was adapted from a reliable and validated dietary intake survey for children.54 The tool has been developed in recognition of the resource burden required to capture ‘usual intake’ using gold standard or objective data collection methodologies such as direct observations of children and/or multiple day plate waste assessments.55 56

The food intake questionnaire requires staff to record the number of serves of each of the Australian Dietary Guideline food groups plus ‘extra’ foods that the child usually consumes across the day, while in care. Research assistants will provide service educators with brief training and a supporting resource, explaining how to accurately complete the child food intake questionnaire. The child food intake questionnaires will be provided to educators during the full day data collection service visit. The questionnaire will only be completed for children aged 2–5 years attending care on the day of data collection. To maximise the number of returned questionnaires, the research team will place a data collection box at the service, which will be collected 1 week post the full day data collection service visit. One member of the research team will be responsible for monitoring and following up the return of the child food intake questionnaires.

Intervention acceptability

As part of the follow-up pen and paper questionnaires, services allocated to the intervention group will answer items related to the use, appropriateness and satisfaction with the resources, training and ongoing support provided by the implementation team. Both the service cook and service manager will answer these acceptability items. The items are not validated and will be similar to those used by the research team to evaluate previous health promotion programmes in childcare services.57 The items will be answered on a four-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree).

Contamination and co-intervention

Intervention contamination and receipt of other interventions provided separate to the trial will be assessed via pen and paper questionnaires completed by service cooks and service managers both in intervention and control groups at follow-up. The questionnaire items will assess if the control services were exposed to any intervention materials or support during the study period. If the participants received any additional support to improve menu planning or food preparation during the study period, they will be asked to describe such support.

Context

A systematic search will be conducted to aid the assessment of the external validity of the trial findings and to describe the context in which the trial was conducted. The search will include national and state education websites, local newspaper archives and accreditation and national healthy eating recommendations and guidelines to identify any changes in government policy, standards, sector accreditation requirements and nutrition guidelines that may impact on the healthy eating environment and the provision of healthy foods within the childcare setting. The date of events and release of promotional materials related to the dissemination of the Caring for Children resource will also be documented. The search will include the 12 months prior to and the 6 months during intervention delivery.

Delivery of intervention strategies

Project records maintained by implementation support staff will be used to monitor and assess the delivery and uptake of each of the intervention strategies.

Provision of tools and resources: the type of tools/resources provided to each intervention service will be monitored and recorded, along with the date they were distributed.

Provision of staff training: the name of the service manager and service cook who attended the 1-day menu planning workshop will be recorded by implementation support officers. In addition, the date and location of the workshop of each intervention service attended will be documented.

Executive support: a copy of the goals developed by intervention service cooks and service managers will be collected by implementation support officers at the completion of the 1-day menu planning workshop.

Audit and feedback: the date each menu assessment is completed and feedback report provided to intervention services will be recorded by implementation support officers.

Ongoing support (newsletters, follow-up service visits/calls): the date and frequency of support contacts by implementation support officers to each service will be recorded.

Minimising attrition

Evidence-based strategies will be employed to minimise study attrition.58 Specifically, strategies include allocating one research assistant to monitor follow-up data collection, using multiple modes of contact (including phone, face-to-face and email) to collect data and sending reminder letters and emails to services that have not provided follow-up data.58 To minimise burden to services, the data collection site visits will be scheduled at a convenient time for the services and the pen and paper questionnaires will be of an appropriate length to complete.

Data entry

Hard copies of data will be stored in lockable filing cabinets, at the Hunter New England Population Health Facility, to which only the study team will have access. Electronic data will be stored on password-protected computers and within a secure electronic database. The pen and paper questionnaire will be coded by a trained research assistant, then checked by the chief investigator and one other investigator. This same coding process will be undertaken for the educator-completed usual food intake questionnaires. To ensure data quality, double data entry will be conducted for 10% of all data for each measure.

Sample size and power calculations

Services implementation of nutrition guidelines (compliant/non-compliant)

Allowing for a 13% compliance rate in the control group, the recruitment of 29 services in the intervention group and 29 services in the control group will enable the detection of an absolute difference of 32% in primary outcome at follow-up, with 80% power, using a two-sided α of 0.05.17

Statistical analysis

The primary trial outcome will be assessed by comparing group differences in proportion of services having 2-week menus which are compliant with nutrition guidelines (providing 50% of recommended serves of the AGHE food groups per child per day). The software used for all statistical analyses will be SAS (V.9.3 or later). The primary trial outcome will be analysed under an intention-to-treat framework, with services being analysed on the basis of the groups to which they were allocated, regardless of the treatment type or exposure received.59 All statistical tests will be two-tailed with an α value of 0.05. A logistic regression model, adjusted for baseline values of the primary trial outcome will be used to determine intervention effectiveness. All available data will be used for the analysis. Sensitivity analyses, using multiple imputations for missing data will also be performed to assess the robustness of the findings of the primary analyses.

Discussion

The limited available evidence regarding the implementation of nutrition guidelines in menu-based childcare services highlights the need for further intervention studies to support childcare services to implement these guidelines. The strengths of this trial include its randomised design, the use of the theoretical domains framework to guide intervention strategy selection to target barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the childcare nutrition guidelines and rigorous assessment of primary and secondary outcome measures. This trial will provide strong evidence to advance implementation research in this setting and allow assessment of the impact on child diet. This randomised controlled trial is the first in the childcare setting to assess the impact of improving guideline implementation on child dietary intake.

Conclusion

This paper describes the design; delivery and evaluation of a randomised trial to support childcare services’ implementation of nutrition guidelines. The proposed trial addresses a gap in the literature by applying implementation theory to inform the design and development of an intervention to improve childcare centres’ implementation of nutrition guidelines. The trial will be the first national randomised trial of its type and is likely to represent a substantial contribution to the literature in this field.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of the Good for Kids, Good for Life Early Childhood Education and Care advisory group.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS led the development of this manuscript. KS, SLY, MF and LW conceived the intervention concept. KS, SLY, MF, JJ and LW contributed to the research design and trial methodology. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: This project received funding from the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour, University of Newcastle Australia and Hunter New England Population Health Wallsend Australia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval to conduct the study has been obtained from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: 06/07/26/4.04). Evaluation data and process data collected as part of the study may be presented at scientific conferences, be published within scientific journals, form part of student theses. Participant's confidentiality will be maintained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Search Global Burden of Disease Data. 2014. 16-2-2015.

- 2.Shrestha R, Copenhaver M. Long-term effects of childhood risk factors on cardiovascular health during adulthood. Clin Med Rev Vasc Health 2015;7:1–5. 10.4137/CMRVH.S29964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waxman A. Prevention of Chronic Diseases: WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 2003;24:281–4. 10.1186/1475-2891-13-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikkelsen MV, Husby S, Skov LR et al. . A systematic review of types of healthy eating interventions in preschools. Nutr J 2014;13:56 10.1186/1475-2891-13-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health and Medical Research Council Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council 2013. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf

- 6.American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: benchmarks for nutrition in child care settings. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:979–86. 10.1016/j.jada.2005.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Local Authorities Coordinators of Regulatory Services. Nursery school nutrition survey results. London: Local Government Association, 2010. 10-2-2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoong SL, Skelton E, Jones J et al. . Do childcare services provide foods in line with the 2013 Australian Dietary guidelines? A cross-sectional study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2014;38:595–6. 10.1111/1753-6405.12312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard CM, Lewis JM, Miller MR. Food service in long day care centres—an opportunity for public health intervention. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23:606–11. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore H, Nelson P, Marshall J et al. . Research report: laying foundations for health: food provision for under 5s in day care. Appetite 2005;44:207–13. 10.1016/j.appet.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NSW Ministry of Health. Caring for children birth to 5 years. North Sydney: NSW Government, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston Molloy C, Kearney J, Hayes N et al. . Pre-school manager training: a cost-effective tool to promote nutrition- and health-related practice improvements in the Irish full-day-care pre-school setting. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:1554–64. 10.1017/S1368980013002760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin SE, Ammerman AS, Sommers JK et al. . Nutrition and physical activity self-assessment for child care (NAP SACC): results from a pilot intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav 2007;39:142–9. 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollard C, Lewis J, Miller M. Start right-eat right award scheme: implementing food and nutrition policy in child care centers. Health Educ Behav 2001;28:320–30. 10.1177/109019810102800306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward DS, Benjamin SE, Ammerman AS et al. . Nutrition and physical activity in child care: results from an environmental intervention. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:352–6. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams CL, Bollella MC, Strobino BA et al. . “Healthy-Start”: Outcome of an intervention to promote a heart healthy diet in preschool children. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;21:62–71. 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell AC, Davies L, Finch M et al. . An implementation intervention to encourage healthy eating in centre-based child-care services: impact of the Good for Kids Good for Life programme. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:1610–19. 10.1017/S1368980013003364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matwiejczyk L, McWhinnie JA, Colmer K. An evaluation of a nutrition intervention at childcare centres in South Australia. Health Promot J Aust 2007;18:159–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkon A, Crowley AA, Neelon SEB et al. . Nutrition and physical activity randomized control trial in child care centers improves knowledge, policies, and children's body mass index. BMC Public Health 2014;14:215 10.1186/1471-2458-14-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy L, King L, Kelly B et al. . Munch and Move: evaluation of a preschool healthy eating and movement skill program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:80 10.1186/1479-5868-7-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landers M, Warden R, Hunt K et al. . Nutrition in long day child care centres: are the guidelines realistic? Aust J Nutr Diet 1994;51:186–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neelon SEB, Burgoine T, Hesketh KR et al. . Nutrition practices of nurseries in England. Comparison with national guidelines. Appetite 2015;85:22–9. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New South Wales Department of Health. Population health division: the health of the people of New South Wales—report of the Chief Health Officer. 2006.

- 24.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011 Census of Population Health and Housing – Community Profiles. 2012. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/communityprofiles?opendocument&navpos=230

- 25.Wyse RJ, Wolfenden L, Campbell E et al. . A cluster randomised trial of a telephone-based intervention for parents to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in their 3- to 5-year-old children: study protocol. BMC Public Health 2010;10:216 10.1186/1471-2458-10-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones J, Wolfenden L, Wyse R et al. . A randomised controlled trial of an intervention to facilitate the implementation of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices in childcare services. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005312 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finch M, Wolfenden L, Falkiner M et al. . Impact of a population based intervention to increase the adoption of multiple physical activity practices in centre based childcare services: a quasi experimental, effectiveness study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:101 10.1186/1479-5868-9-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finch M, Wolfenden L, Morgan PJ et al. . A cluster randomised trial to evaluate a physical activity intervention among 3–5 year old children attending long day care services: study protocol. BMC Public Health 2010;10:534 10.1186/1471-2458-10-534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Dusseldorp E et al. . Measuring determinants of implementation behavior: psychometric properties of a questionnaire based on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci 2014;9:33 10.1186/1748-5908-9-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finch M, Yoong SL, Thomson RJ et al. . A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of an implementation intervention to increase healthy eating and physical activity-promoting policies, and practices in centre-based childcare services: study protocol. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006706 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J et al. . From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol 2008;57: 660–80. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.French SD, Green SE, O'Connor DA et al. . Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci 2012;7:38–45. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:37 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ et al. . Experiences of using the Theoretical Domains Framework across diverse clinical environments: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2015;8:139–46. 10.2147/JMDH.S78458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarmast H, Mosavianpour M, Collet JP et al. . TDF (Theoretical Domain Framework): how inclusive are TDF domains and constructs compared to other tools for assessing barriers to change? BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:81.24559177 [Google Scholar]

- 36.French SD, McKenzie JE, O'Connor DA et al. . Evaluation of a theory-informed implementation intervention for the management of acute low back pain in general medical practice: The IMPLEMENT Cluster Randomised Trial. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e65471 10.1371/journal.pone.0065471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dyson J, Lawton R, Jackson C et al. . Development of a theory-based instrument to identify barriers and levers to best hand hygiene practice among healthcare practitioners. Implement Sci 2013;8:111 10.1186/1748-5908-8-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Gruen RL et al. . Understanding practice: the factors that influence management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department-a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci 2014;9:8 10.1186/1748-5908-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Crone MR et al. . Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implement Sci 2014;9:11 10.1186/1748-5908-9-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forsetlund l, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A et al. . Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD003030 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joyce B, Showers B. Improving in service training: the message of research. Educ Leaders 1980;37:379. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM et al. . Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ 1998;317:465–8. 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charles WR, Brian HK. Which training methods are effective? Manage Dev Rev 1996;9:24–9. 10.1108/09622519610111781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rohrbach LA, Grana R, Sussman S et al. . Type II translation: transporting prevention interventions from research to real-world settings. Eval Health Prof 2006;29:302–33. 10.1177/0163278706290408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S et al. . Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6:CD000259 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–87. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA 1990;263:549–56. 10.1001/jama.1990.03440040088034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones RA, Riethmuller A, Hesketh K et al. . Promoting fundamental movement skill development and physical activity in early childhood settings: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2011;23:600–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson S et al. . Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance misuse: systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:238–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolfenden L, Wiggers J, Campbell E et al. . Feasibility, acceptability, and cost of referring surgical patients for postdischarge cessation support from a quitline. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:1105–8. 10.1080/14622200802097472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodds P, Wyse R, Jones J et al. . Validity of a measure to assess healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices in Australian childcare services. BMC Public Health 2014;14:572 10.1186/1471-2458-14-572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ginani VnC, Zandonadi RP, Araujo WMC et al. . Methods, instruments, and parameters for analyzing the menu nutritionally and sensorially: a systematic review. J Culinary Sci Technol 2012;10:294–310. 10.1080/15428052.2012.728981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacko CC, Dellava J, Ensle K et al. . Use of the plate-waste method to measure food intake in children. J Extension 2007;45:6RIB7. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hendrie GA, Viner Smith E, Golley RK. The reliability and relative validity of a diet index score for 4-11-year-old children derived from a parent-reported short food survey. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1486–97. 10.1017/S1368980013001778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ball SC, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. Development and reliability of an observation method to assess food intake of young children in child care. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:656–61. 10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erinosho T, Dixon LB, Young C et al. . Nutrition practices and children's dietary intakes at 40 child-care centers in New York City. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1391–7. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones J, Wyse R, Finch M et al. . Effectiveness of an intervention to facilitate the implementation of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices in childcare services: a randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci 2015;10:147 10.1186/s13012-015-0340-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brueton VC, Tierney JF, Stenning S et al. . Strategies to improve retention in randomised trials: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003821 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.White IR, Horton NJ, Carpenter J et al. . Strategy for intention to treat analysis in randomised trials with missing outcome data. BMJ 2011;342:d40 10.1136/bmj.d40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]