Abstract

Objective

To assess whether a novel ‘direct access pathway’ (DAP) for the management of high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTEACS) is safe, results in ‘shorter time to intervention and shorter admission times’. This pathway was developed locally to enable London Ambulance Service to rapidly transfer suspected high-risk NSTEACS from the community to our regional heart attack centre for consideration of early angiography.

Methods

This is a retrospective case–control analysis of 289 patients comparing patients with high-risk NSTEACS admitted via DAP with age-matched controls from the standard pan-London high-risk ACS pathway (PLP) and the conventional pathway (CP). The primary end point of the study was time from admission to coronary angiography/intervention. Secondary end point was total length of hospital stay.

Results

Over a period of 43 months, 101 patients were admitted by DAP, 109 matched patients by PLP and 79 matched patients through CP. Median times from admission to coronary angiography for DAP, PLP and CP were 2.8 (1.5–9), 16.6 (6–50) and 60 (33–116) hours, respectively (p<0.001). Median length of hospital stay for DAP and PLP was similar at 3.0 (2.0–5.0) days in comparison to 5 (3–7) days for CP (p<0.001).

Conclusions

DAP resulted in a significant reduction in time to angiography for patients with high-risk NSTEACS when compared to existing pathways.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, non- ST elevation MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, clinical pathway

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of direct access pathway (DAP) appears to be safe and effective in patients admitted with high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Using DAP can reduce time from admission to coronary angiography and length of in-hospital stay significantly.

DAP may potentially ease the in-hospital bed pressures, thus easing current 4-hour treatment targets imposed on UK emergency departments.

This is a retrospective case–control analysis with associated limitations.

Cost–benefit analysis of using direct access pathway was not carried out.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) comprise a spectrum of myocardial events ranging from ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) through to non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina (UA). NSTEMI and UA are now together described under the umbrella term non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS). Over the past decade, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) has become the gold standard for the treatment of STEMI with clear survival benefit when compared to previous therapies.1 However, a uniform treatment strategy does not exist for NSTEACS as they represent a heterogeneous group of patients in terms of their underlying pathology and prognosis. Furthermore, it is evident that patients with NSTEACS with high-risk features have higher mortality when compared to STEMI at 6 months.2 3 As a consequence, international and national guidelines state that all patients presenting with NSTEACS should undergo early risk stratification; with high-risk patients benefitting from angiography within 24 hours or even earlier in those with haemodynamic instability.4 Recently updated guidelines by National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommend invasive treatment within 72 hours of first hospital admission for all patients with intermediate- and high-risk NSTEACS.5 The UK 2014 national Myocardial Infarction National Audit Project (MINAP) reported that 33% of all patients with NSTEACS who underwent angiography did so after 96 hours, without taking into account the delay incurred by interhospital transfer for patients initially presenting to a hospital without an interventional catheter laboratory. The median length of stay without talking into account interhospital transfers for this group was 5 days (IQR 3–9) as per the same report.5 Similarly, the SWEDEHEART registry from Sweden also reported that a third of NSTEACS cases underwent angiography after 72 hours in 2013.6 The delay in NSTEMI patients receiving early angiography, at least in the UK, is partly due to inherent delays in the existing treatment pathways for patients presenting with NSTEACS. In the existing model, patients with NSTEACS are admitted and assessed in the emergency departments (ED) of local district general hospitals (DGHs) or tertiary centres, but then wait for coronary angiography pending assessment by a cardiologist. Existing models are hierarchical, and prior to being considered for angiography, several physicians from ED, general medicine and finally cardiologists would assess patients, thus resulting in delays. To overcome the inherent delay in this model and in order to deliver patients with high-risk NSTEACS directly to cardiologists, a novel pathway was designed. This pathway called ‘direct access pathway’ (DAP) involves paramedic assessment of clinical and ECG high-risk NSTEACS features in the community with direct admission to the heart attack centre (HAC) so that urgent angiography can be considered similar to the pathway for PPCI. In this pathway, the first physician contact is with an interventional cardiologist, at a PCI capable centre, who is in a position to (1) make a swift decision regarding the need for coronary angiography and (2) has round the clock access to the catheter laboratory. This pathway was implemented at the Royal Free Hospital (RFH) with the support of London Ambulance Service (LAS) since 2011. The RFH is a regional HAC, serving a population of ∼750 000 in north London. The hospital is one of the designated primary PCI centres in London and provides a coronary angiography and PCI service to local DGHs. The effectiveness of DAP was compared with the existing pan-London high-risk ACS pathway (PLP)7 and patients admitted conventionally via the existing model (conventional pathway, CP).

Methods

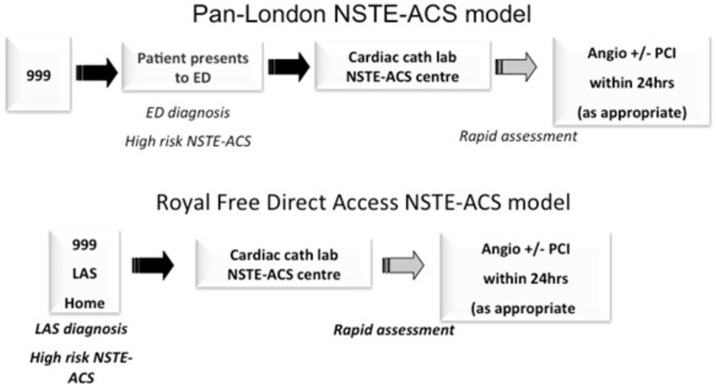

This is a retrospective analysis comparing the performance of a newly initiated pathway for the care of patients with high-risk NSTEACS with existing pathways. The analysis included all patients admitted with high-risk NSTEACS between March 2011 and October 2014. The study was registered with the RFH clinical governance department. As this was retrospective analysis, consent from patients was not deemed necessary by the hospital research and development department. The study pathways, with their individual inclusion criteria, are detailed in table 1. Schematic flow diagrams of the PLP and DAP pathways are shown in figure 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for DAP, PLP and CP

| DAP | PLP | CP |

|---|---|---|

Patients with on-going chest pain and with any of the following additional haemodynamic or electrocardiographic features:

|

|

Patients admitted either via the ED, GP referrals or from local DGH medical departments with suspected NSTEACS and high-risk features as per Pan-London high-risk pathwayPatients not appropriately triaged and undergo conventional (delayed) angiography |

CP, conventional pathway; DAP, direct access pathway; DGH, district general hospital; ED, emergency department; NSTEACS, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndrome; PLP, pan-London high-risk ACS pathway.

Figure 1.

Flow charts depicting PLP and DAP. 999, UK emergency services contact number; DAP, direct access pathway; ED, emergency department; LAS, London Ambulance Service; NSTEACS, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndromes; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PLP, pan-London high-risk ACS pathway.

Direct access pathway

Patients admitted via DAP were directly transferred from the community to the RFH heart attack service and were immediately assessed by a consultant cardiologist or a cardiology registrar, and decision to perform urgent angiography was made based on the inclusion criteria in table 1. Patients deemed to be high risk but without on-going chest pain were admitted directly to monitored cardiac ward, started on evidence-based therapy and angiography was performed within 24 hours. All other patients underwent immediate angiography. The index assessment for the activation of this pathway was undertaken by paramedic staff in the community. Troponin elevation was not included in the activation criteria so as to reduce delay and allow activation of the pathway in the community (figure 1).

Pan-London high-risk ACS pathway

PLP was implemented in 2012 across several cardiovascular networks in London to expedite the transfer of patients with NSTEACS to a centre where angiography can be performed (figure 1 and table 1).7 The source of activation for the PLP can be in the ED or medical take at local DGHs. Appropriate patients were transferred by emergency ambulance to a cardiac centre where evidence-based medical therapy was started and a decision on whether to proceed with early angiography was then made.

Conventional pathway

The existing model of care is described as the CP. A wide variety of referral sources for patients suspected of NSTEACS are reviewed in ED by emergency physicians and usually the medical take team (table 1). The referral sources included general practitioners and self-presenters. Patients in this group had similar high-risk features to the PLP group but were not identified as high risk at source and were referred for conventional delayed angiography as interhospital transfers. These patients were identified and included in the study following their admission to cardiology ward or at the time of coronary angiography.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had any usual contraindication to early interventional management and if an alternative diagnosis to NSTEACS was strongly suspected.

Outcome measures

The primary study end point was time to coronary angiography for patients with NSTEACS. This was defined as arrival at the cardiac unit to beginning of angiography for DAP and time of registration at the DGH or RFH ED to beginning of the angiogram procedure for the other two pathways. Secondary end points included length of in-hospital stay and 30-day mortality across three groups.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data with a normal distribution were reported as mean±SD. Non-parametric data were reported as median and IQR. Categorical data were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Data across three groups were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test and then Mann-Whitney U tests for intergroup differences. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Demographics and baseline characteristics are presented in table 2. Two hundred and eighty-nine patients with NSTEACS were included in the study and separated by pathway (n=101 patients in the DAP, n=109 patients in the PLP and n=79 patients in the CP). The mean age was broadly similar across the groups. DAP had a higher percentage of male patients in comparison to the other groups. Aside from a significantly higher frequency of male patients and patients with previous history of hypertension in the DAP, there were no other variables with statistically significant difference between the groups.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| DAP (%) | PLP (%) | CP (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.7 (SD 13.31) | 685 (SD 15.1) | 69.5 (SD 11.5) | 0.8 |

| Sex (male) | 76.2 | 67.5 | 64.5 | |

| Hypertension | 55.4 | 37 | 35 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 29 | 26 | 31 | 0.15 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 39.6 | 45 | 30 | 0.09 |

| Smoker | 22 | 19 | 17 | 0.7 |

| Family history of CAD | 21 | 20 | 13 | 0.7 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 9 | 10 | 0.6 |

| Previous PCI | 8 | 9 | 7 | 0.9 |

| Previous CABG | 7 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 0.5 |

| CVA | 6 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 0.4 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CP, conventional pathway; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DAP, direct access pathway; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PLP, pan-London high-risk ACS pathway.

Outcome of invasive investigation

Ninety-eight (97%) patients in DAP, 105 (96%) patients in PLP and 75 (95%) patients in CP underwent coronary angiography. Seventy-three (74.7%) patients in DAP, 71 (67.7%) patients in PLP and 62 (78.6%) patients in CP underwent PCI. Eight (8.1%) patients in DAP, six (5.7%) patients in PLP and eight (10.4%) patients in CP underwent coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG). The remaining were treated with medical therapy. A proportion of patients who were treated with medical therapy across three groups included those with angiographically severe triple vessel disease. This group of patients did not undergo PCI or CABG as they were deemed not suitable for either strategy following a discussion at multidisciplinary team meeting and were thought to be best served by medical therapy.

Time to coronary angiography

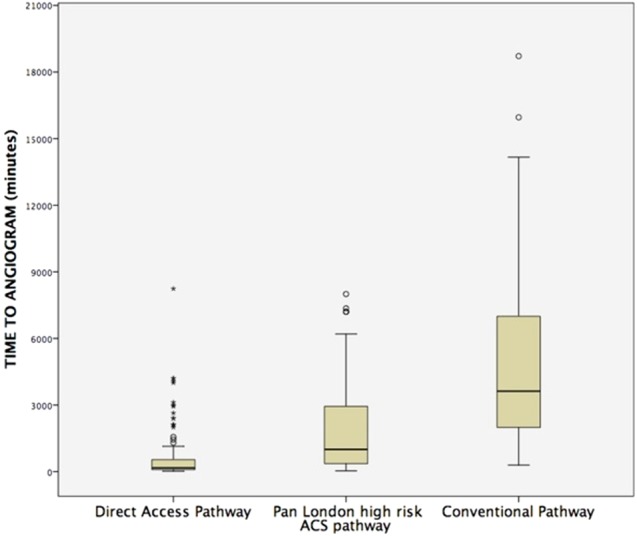

The median time from admission to coronary angiography for DAP, PLP and CP was 2.8 (1.5–9), 16.6 (6–50) and 60 (33–116) hours, respectively (p<0.001) (figure 2). One hundred and fifty-two (54.3%) patients underwent angiography within first 24 hours. The highest percentage of patients undergoing angiography within 24 hours was in the DAP group (n=82, 83.7%).

Figure 2.

Box plots depicting the time to angiography across three groups.

Length of hospital stay

The median length of hospital stay was significantly higher in the CP compared to DAP and PLP groups (5 (3–7) vs 3 (2–5) and 3(2–5) days, respectively; p<0.001 and 0.001).

30-Day mortality

Overall mortality across three groups was small (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of key metrics across three pathways

| N=289 | DAP (a) (n=101) |

PLP (b) (n=109) |

CP (c) (n=79) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital stay Median (days) (IQR) |

3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 5 (3–7) | <0.001a–c 0.001b,c 0.3a,b |

| Cases undergoing angiography (%) | 98 (97%) | 105 (96%) | 75 (95%) | 0.9 |

| PCI (%) | 73 (74.7%) | 71 (67.7%) | 62 (78.6%) | 0.003a,b <0.001a–c 0.003b,c |

| CABG (%) | 8 (8.1%) | 6 (5.7%) | 8 (10.4%) | 0.4 |

| Time to angiogram Median (hours) (IQR) |

2.8 (1.5–9) | 16.6 (6–50) | 60 (33–116) | <0.001a–c <0.001a,b <0.001b,c |

| Angiography <24 hours 152 (54.3%) |

82 (83.7%) | 62 (59.04%) | 8 (10.7%) | <0.001a–c <0.001a,b <0.001b,c |

| 30-Day mortality | 2 (0.02%) | 1 (0.02%) | 3 (0.04%) | 0.5 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CP, conventional pathway; DAP, direct access pathway; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PLP, pan-London high-risk ACS pathway.

Discussion

The principal finding of our study was a significant reduction in admission time to angiography in patients with high-risk NSTEACS admitted via DAP when compared to other pathways. Furthermore, DAP also has a shorter length of hospital stay for patients with NSTEACS when compared to control pathway but similar length of stay when compared to PLP and a similar 30-day mortality to other pathways. A further remarkable observation was that despite activation by paramedics in the community, in comparison to physicians in hospital, there was a similar percentage of patients who required angiography and importantly had follow-on revascularisation (PCI or CABG) in the DAP when compared to the other two groups. This study suggests that the diagnostic yield for ‘genuine’ culprit lesion-related ACS using the DAP is as good as the other pathways, and it supports the notion that paramedics can be used to identify patients with high-risk features early on in the patient journey. Through this pathway, we have also demonstrated that high-risk NSTEACS can be rapidly assessed by a cardiologist and be offered angiography in a timely fashion in line with current guidelines.

The care provided to patients with NSTEMI differs substantially between countries and continents despite a strong evidence base.8 However, one aspect on which there is consensus is that of an early invasive/interventional strategy.9 10 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of Angioplasty to Blunt the Rise of Troponin in Acute Coronary Syndromes Randomised for an Early or Delayed Intervention (ABOARD),11 Timing of Intervention in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes (TIMACS),10 Intracoronary Stenting With Antithrombotic Regimen Cooling Off (ISAR-COOL)12 and Early or Late Intervention in unStable Angina (ELISA)13 trials have shown early invasive strategy to be safe, effective and reduce the length of hospital stay.14 However, the reality is different with healthcare systems struggling to provide an early invasive strategy to patients with NSTEACS. According to the 2014 UK MINAP report, only two-thirds of patients admitted with NSTEACS underwent angiography within 96 hours. According to the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society audit, a national registry of percutaneous coronary interventions in England and Wales for the year 2013–2014, only 55% underwent angiography within first 72 hours,15 a target now set by the NICE in the amended NSTEMI treatment guidelines. This clinical target of offering angiography to all high-risk patients with NSTEACS within 72 hours of admission is a challenging prospect for most healthcare systems due to the inherent delay associated with the initial triage and management delivered by ED and general physicians. Several pathways for patients presenting with NSTEMI have been described previously. Bellenger et al reported their experience of a regional transfer unit (RTU) to treat ACS in 2006. Angiography was performed within 24 hours of arrival of patients from DGH to the RTU. In their model, the mean waiting time from referral to angiography was reduced from 20 to 8 days—a 62% reduction.16 Recently Gallagher et al17 reported a significant reduction in the median time from ED admission to coronary angiography and length of hospital stay following introduction of a novel HAC—Extension (HAC-X) pathway for patients presenting with NSTEACS in East London. In the HAC-X pathway, patients presenting to their local DGH with NSTEACS were triaged rapidly and transferred to a tertiary centre whereby early angiography was performed. The PLP is designed in similar lines to the HAC-X pathway with the same purpose. DAP was designed with strict inclusion criteria so that LAS can identify patients with NSTEACS who are at high risk and facilitated transfer to an HAC from the community. Perhaps this was one of the reasons why over 90% of patients admitted by DAP underwent angiography. The time to angiography achieved by DAP was much quicker than the PLP perhaps explained by the extra steps involved in the activation of PLP. However, there was no difference in the length of hospital stay between DAP and PLP, reflecting the fact that the shorter time to angiography in DAP did not transform into reduced stay. DAP appears to be feasible, effective and safe. Despite the inherently high-risk features of the patients recruited to the DAP, as required by the inclusion criteria, there was no difference in 30-day mortality when compared to the other pathways. Furthermore, admitting patients with high-risk NSTEACS directly to an HAC, bypassing local ED, may potentially ease the in-hospital bed pressures, thus easing current 4-hour treatment targets imposed on UK ED. However, delivering DAP, a pathway that is similar to PPCI pathway, requires extra resources. This includes the availability of highly trained catheter laboratory staff round the clock, although most HACs have this level of on call cover already in place in order to provide a primary PCI service. In our experience, no extra staff were required to deliver the DAP; however, the feasibility needs to be reassessed with larger numbers. Furthermore, setting up of a DAP requires significant investment in staff and paramedic training but may well be offset by savings in the duration of hospital stay. Our preliminary experience is that LAS paramedics are good discriminators.

Limitations

The limitations associated with retrospective design need recognition. Although we have 30-day mortality data across all three groups, long-term data are not available. Furthermore, it is reassuring that there are no signals from these mortality data that the DAP is associated with harm, but given the small size of the cohorts this study is not sufficiently powered to ascertain a mortality difference. Other potential secondary end points such as the magnitude of myocardial infarction as assessed by troponin area under the curve have not been compared in this study. This is because patients in the DAP underwent coronary angiography and revascularisation in a fashion similar to PPCI and thus only postintervention bloods are available, which may be confounded by intervention-related myocardial injury. Second, troponin assays varied at the local DGHs and HAC, thus making direct comparison difficult. DAP appears to be safe given the fact that the mortality is similar across three groups; however, further analysis including complications, if any, associated with DAP needs to be carried out.

Conclusion

The use of a dedicated DAP, within an already established regional HAC, is effective in patients admitted with high-risk NSTEACS. Furthermore, this rapid access to a senior cardiology opinion and angiography was also associated with a shorter in-hospital stay. These factors may improve patient experience and have a positive health economics impact. Further studies with larger cohorts of patients are warranted to ascertain major cardiovascular event rate differences and cost benefits of admitting patients via a DAP.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK and AS collected and analysed data and prepared the manuscript. MW helped in the collection of data. N and TK reviewed the manuscript and made necessary changes. RDR designed and oversaw the whole project and carried out the final review.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savonitto S, Ardissino D, Granger CB et al. Prognostic value of the admission electrocardiogram in acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 1999;281:707–13. 10.1001/jama.281.8.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen LA, O'Donnell CJ, Camargo CA Jr et al. Comparison of long-term mortality across the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2006;151:1065–71. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project: how the NHS cares for patients with heart attack, London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies. SWEDEHEART annual report, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redefining the NSTEACS pathway in London. The London Cardiovascular Project. London: London Cardiac and Stroke Networks, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNamara RL, Chung SC, Jernberg T et al. International comparisons of the management of patients with non-ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States: the MINAP/NICOR, SWEDEHEART/RIKS-HIA, and ACTION Registry-GWTG/NCDR registries. Int J Cardiol 2014;175:240–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox KA, Clayton TC, Damman P et al. Long-term outcome of a routine versus selective invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2435–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2165–75. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montalescot G, Cayla G, Collet JP et al. Immediate vs delayed intervention for acute coronary syndromes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2009;302:947–54. 10.1001/jama.2009.1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Pogatsa-Murray G et al. Evaluation of prolonged antithrombotic pretreatment (“cooling-off” strategy) before intervention in patients with unstable coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:1593–9. 10.1001/jama.290.12.1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van ‘t Hof AW, de Vries ST, Dambrink JH et al. A comparison of two invasive strategies in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: results of the Early or Late Intervention in unStable Angina (ELISA) pilot study. 2b/3a upstream therapy and acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katritsis DG, Siontis GC, Kastrati A et al. Optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential intervention in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2011;32:32–40. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.British Cardiovascular Interventional Society. Adult interventional procedure audit returns. Blackpool, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellenger NG, Wells T, Hitchcock R et al. Reducing transfer times for coronary angiography in patients with acute coronary syndromes: one solution to a national problem. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:411–13. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.040162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher SM, Lovell MJ, Jones DA et al. Does a ‘direct’ transfer protocol reduce time to coronary angiography for patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes? A prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005525 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]