Abstract

Acquisition of the lower jaw (mandible) was evolutionarily important for jawed vertebrates. In humans, syndromic craniofacial malformations often accompany jaw anomalies. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Hand2, which is conserved among jawed vertebrates, is expressed in the neural crest in the mandibular process but not in the maxillary process of the first branchial arch. Here, we provide evidence that Hand2 is sufficient for upper jaw (maxilla)-to-mandible transformation by regulating the expression of homeobox transcription factors in mice. Altered Hand2 expression in the neural crest transformed the maxillae into mandibles with duplicated Meckel’s cartilage, which resulted in an absence of the secondary palate. In Hand2-overexpressing mutants, non-Hox homeobox transcription factors were dysregulated. These results suggest that Hand2 regulates mandibular development through downstream genes of Hand2 and is therefore a major determinant of jaw identity. Hand2 may have influenced the evolutionary acquisition of the mandible and secondary palate.

The evolution of vertebrates, which first appeared as gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates), is associated with jaw acquisition, as it allowed a shift from passive to active predation1. The evolution of articulated jaws was mainly induced because invertebrates acquired the neural crest2. The upper (maxilla) and lower (mandible) jaws and associated soft tissues are derived from the maxillary and mandibular processes, respectively, of the first branchial arch. The jaws of early gnathostomes consisted of two major components, the palatoquadrate in the upper jaw and Meckel’s cartilage in the lower jaw3,4. Jawed vertebrates are divided into two groups, bony vertebrates and cartilaginous fishes, which are further grouped into two lineages, elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) and holocephalans (elephant sharks and ratfishes). Holocephalans, which are the most primitive of living jawed vertebrates5, have a complete hyoid arch and upper jaw fused to the cranium. Cyclostomes (lampreys) are widely recognised as the closest living relatives of jawless vertebrates1,6,7. In humans, improper development of neural crest cells (NCCs) occurs in at least one-third of all congenital anomalies8. Syndromic craniofacial malformations often accompany mandibular anomalies such as agnathia, micrognathia, retrognathia, and aplasia/hypoplasia of the mandibular condyles. Therefore, the identification of factors involved in mandible specification will provide insights into the evolution of vertebrates and the mechanisms underlying congenital anomalies involving craniofacial tissues.

The Hand protein family of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors in higher species consists of two members, Hand1 and Hand2. Ablation of Hand2 expression in NCCs of the branchial arches results in hypomorphism of the mandibles and Meckel’s cartilage in mice9,10,11. The NCCs in the first branchial arch are devoid of Hox homeobox genes, and Hox gene expression in the first branchial NCCs is incompatible with jaw formation12. Instead, non-Hox homeobox transcription factors, which are expressed in the first branchial arch, have broad potential to produce most of the cartilaginous and dermatocranial derivatives13. Dlx homeobox transcription factors, which specify the dorsoventral patterning of the first branchial arch, have been involved in vertebrate evolution4,14. Dlx6 acts as an intermediary between endothelin1 (Edn1)/endothelin receptor type A (Ednra)-mediated signalling and Hand2 expression during mandibular development15,16, although Hand2 expression in the ventral region of the branchial arch is independent of Edn1/Ednra-mediated signals9. The loss of Dlx5/Dlx6 or Ednra in mice results in homeotic transformation of the lower jaws to the upper jaws4,17,18, whereas the constitutive activation of Ednra expression induces ectopic expression of Hand2 in the maxillary arch and subsequently transforms the upper jaws into lower jaws19,20. In 66% of EdnraHand2/+ mutants, in which one copy of Hand2 was knocked into the Ednra locus, exhibit the transformation of upper jaw structures into lower jaw elements19. In the Japanese lamprey Lethenteron japonicum, a Hox-expression-free mandible has been maintained21 and homologs of Edn1, Ednra, and Hand2 are expressed as in gnathostomes22, thus indicating that the regulation of Hand2 gene expression in the branchial arch is conserved in cyclostomes and gnathostomes.

Here, we show that altered expression of the Hand transcription factors, Hand1 and Hand2, in NCCs or the osteochondral progenitors induced the transformation of the upper jaw into a lower jaw, which resulted in a missing secondary palate. We identified that Hand2 was specifically located genetically upstream of non-Hox homeobox transcription factors in the development of the first branchial arch. Modification of the Hand2 gene may correlate with the evolution of vertebrates.

Results

Altered expression of Hand2 induces the transformation of the upper jaw to the lower jaw

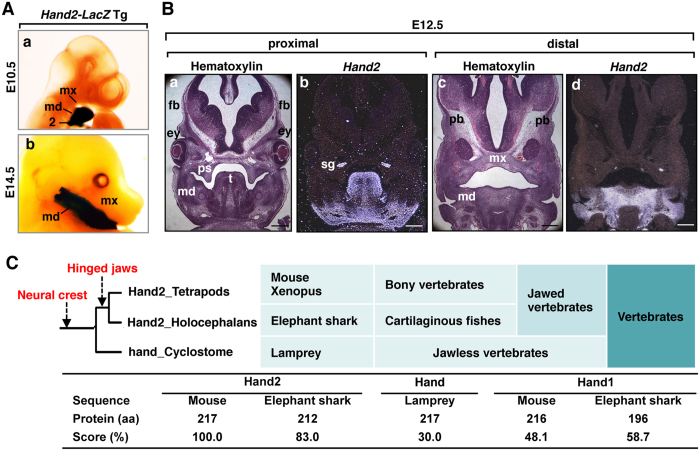

The bHLH transcription factor Hand2 controls cardiac, limb, and craniofacial development9,11,15,23,24. When we analysed the whole-mount LacZ expression that was driven by the 11-kb Hand2 promoter in the craniofacial region, Hand2 expression was observed exclusively in the mandibular arch but not in the maxillary arch or calvarial regions (Fig. 1A). The nested expression of the Hand2 gene in the mandibular region was also confirmed by in situ hybridization (Fig. 1B). Because the acquisition of the mandible was especially important in the evolution of vertebrates and Hand2 expression is nested in the mandibular arch, the amino-acid alignment of the Hand proteins was examined. Interestingly, Hand2 is evolutionally conserved in primitive jawed vertebrates (elephant sharks) but less conserved among jawless vertebrates (lampreys) and invertebrates (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Figs S1 and S2).

Figure 1. Nested expression of Hand2 in the mandibular arch.

(A) Whole-mount β-galactosidase staining of Hand2-LacZ transgenic embryos at embryonic day (E) 10.5 (a) and E14.5 (b). md, mandibular arch; mx, maxillary arch; 2, the second branchial arch. (B) Hand2 (b,d) was detected by in situ hybridization on coronal sections from the wild-type head at E12.5. Adjacent control sections are stained with hematoxylin (a,c). Hand2 expression is nested in the mandibular process (md). mx, maxillary process; fb, frontal bone; ps, palatal shelf; t, tongue; pb, parietal bone; sg, sympathetic ganglion. Scale bars: 300 μm. (C) Genetic events and phylogeny of the Hand2 coding sequences.

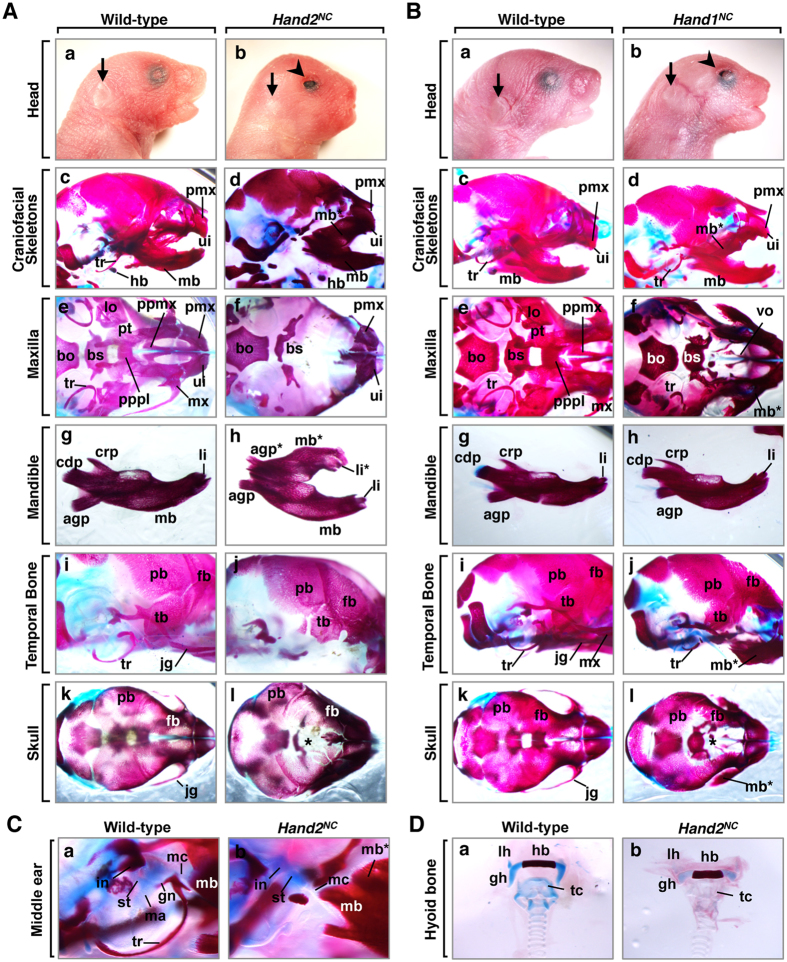

The correlation of the pattern of the nested expression of Hand2 in the mandibular arch (Fig. 1A,B) and the phylogenetic tree of Hand2 (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. S1) suggested that Hand2 might determine the mandibular identity within the first branchial arch. NCCs, which contribute to jaw and craniofacial evolution, have been implicated in the patterning of craniofacial cartilaginous and dermatocranial derivatives25. To explore the hypothesis that Hand2 specifies the identity of jaws within the NCCs of the branchial arches, we overexpressed Hand2 specifically in the NCCs of mice and examined the resulting craniofacial phenotypes. At postnatal day (P) 1, all (16 of 16) Hand2CAT/+; Wnt1-Cre (hereafter Hand2NC) mice died neonatally with craniofacial deformities, including brachycephaly, eyelid colobomas, tongue protrusion, and small pinna in the anterior position, compared to control littermates (Fig. 2Ab; Supplementary Table S1). Alizarin red and alcian blue staining showed that the maxillary elements (maxillary bone, palatal process of maxilla and palatine, vomer, pterygoid, lamina obturans, and jugal bones) were aplastic in Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 2Af; Supplementary Table S2) and that these elements were replaced by mirror-image duplication of the mandibular bone with duplicated lower incisors and mandibular molar alveoli (Fig. 2Ad,f,h). The mutant mandibular bones and angular processes of the mandible were hypoplastic, and the coronoid and condylar processes were aplastic (Fig. 2Ah). The duplicated mandibular bone was fused to the original mandibular bone at the condylar process and attached to the premaxilla (Fig. 2Ad,h). The premaxilla, which is a derivative of the frontonasal process (FNP), was mildly deformed, while the upper incisors within the premaxilla were maintained in Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 2Af). The pterygoid, presphenoid, and basisphenoid bones, which are derivatives of the neural crest, were aplastic or severely malformed, whereas the basioccipital bone, which is a derivative of the mesoderm, was intact (Fig. 2Af). The temporal bones were reduced and fragmented in Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 2Aj). Compared with the wild-type mice, the neural crest-derived frontal bones were much reduced in size in Hand2NC mutants, whereas the mesoderm-derived parietal bones were similar in size (Fig. 2Ak,l). The mutant skulls showed brachycephaly (Fig. 2Ak,l), suggesting that skull shape was sensitive to the patterning information from the tissue at the junction of the maxillary process. In the middle ear, derivatives of the first branchial arch (malleus, incus, gonial bone, and tympanic ring) failed to form (Fig. 2C). The hyoid bones, which are derivatives of the second branchial arch, were maintained; however, the ossification was hypoplastic in Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Patterning defects in neural crest-specific Hand2- and Hand1-induced mutants.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of Hand2CAT/+; Wnt1-Cre (Hand2NC) mice. (a,b) Facial appearance of postnatal day (P) 1 wild-type (a) and Hand2NC (b) mice. Hand2NC mutants (b) exhibit brachycephaly, eyelid colobomas (arrowhead in b), and small pinna (arrow in b). (c–l) Alizarin red (mineralised bone) and alcian blue (cartilage) staining of P1 wild-type (c,e,g,i,k) and Hand2NC (d,f,h,j,l) mice. Hand2NC mutants demonstrate the transformation of the maxilla (mx) into a duplicated mandibular bone (mb*), which appears as a mirror image of the mandibular bone (mb). Hypoplasia of the frontal bones (fb) and frontal foramina (asterisk) are observed in the skull vault of Hand2NC mutants (l). (B) Phenotypic analysis of Hand1CAT/+; Wnt1-Cre (Hand1NC) mice. (a,b) Facial appearance of P1 wild-type (a) and Hand1NC (b) mice. Hand1NC mutants (b) exhibit brachycephaly, eyelid colobomas (arrowhead in b), and small pinna (arrow in b). (c–l) Bone staining of P1 wild-type (c,e,g,i,k) and Hand1NC (d,f,h,j,l) mice. Hand1NC mutants have a partially duplicated mandible (mb*). Hypoplasia of the frontal bones (fb) and frontal foramina (asterisk) are observed in the skull vault of Hand1NC mutants (l). (C) The middle ear phenotype of P1 wild-type (a) and Hand2NC (b) mice. In wild-type mice (a), the malleus (ma), incus (in), stapes (st), gonial bone (gn), tympanic ring (tr), and Meckel’s cartilage (mc) are observed. In Hand2NC mutants, the malleus, gonial bone, and tympanic ring are absent or hypomorphic. (D) The hyoid bone phenotype of P1 wild-type (a) and Hand2NC (b) mice. The ossification of the hyoid bones is hypoplastic in Hand2NC mutants. mx, maxilla; mb*, duplicated mandibular bone; mb, mandibular bone; fb, frontal bone; tr, tympanic ring; lo, lamina obturans; jg, jugal bones; tb, temporal bone; bs, basisphenoid bone; ui, upper incisors; li, lower incisors; li*, duplicated lower incisors; bo, basioccipital bone; pmx, premaxilla; hb, hyoid bone; pt, pterygoid; ppmx, palatal process of maxilla; pppl, palatal process of palatine; agp, angular process; crp, coronoid process; cdp, condylar process; pb, parietal bone; vo, vomer; hy, hyoid bone, with lesser (lh) and greater (gh) horns; tc, thyroid cartilage.

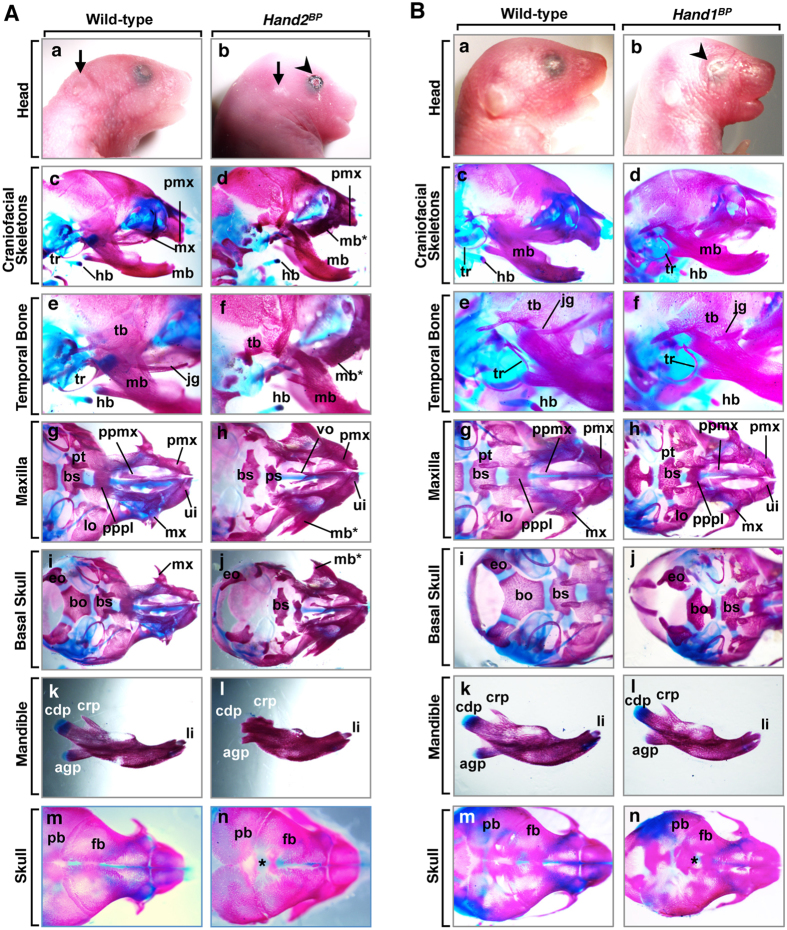

To understand the physiological role of Hand2 in the bone development of the branchial arches, we overexpressed Hand2 in the early precursors of all of the cell types of the bone primordium with Twist2-Cre knockin mice26. All Hand2CAT/+; Twist2-Cre (hereafter Hand2BP) mice died neonatally with severe craniofacial defects, including brachycephaly, eyelid colobomas, and small pinna (Fig. 3A), which were similar to the defects observed in the Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 2A). In Hand2BP mutants, the maxillary structures (the palatal process of the maxilla and palatine jugal bones) were missing and replaced by a partially duplicated set of mandibular bones with a mandibular molar alveolus (Fig. 3A). These skeletal abnormalities of Hand2BP mutants were similar to but milder than those seen in Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 2A), except for the basioccipital bones (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S2). These results indicate that Hand2 in the NCCs contribute as a selector gene to the specification of the mandibular bone. The abnormalities were not observed in Hand2CAT/+ mice (n = 16).

Figure 3. Craniofacial dysmorphism resulting from conditional activation of Hand2 or Hand1 by Twist2-Cre.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of Hand2BP mice. (a,b) Facial appearance of P1 wild-type (a) and Hand2BP (b) mice. The Hand2BP mutant exhibits brachycephaly, eyelid colobomas (arrowhead), and small pinna (arrow) (b). (c–n) Alizarin red and alcian blue staining of P1 wild-type and Hand2BP mice, as indicated. Hand2BP mutants show partial maxilla-to-mandible transformation (d,f,h,j). The tympanic ring (tr), jugal bone (jg), and basioccipital bone (bo) are aplastic in Hand2BP mutants (f,j). The condylar processes and temporal bone (tb) of Hand2BP mutant are severely hypoplastic (l). Hypoplasia of the frontal bones (fb) and open frontal foramina (asterisk) are observed in the skull vault of Hand2BP mutants (n). (B) Phenotypic analysis of Hand1BP mice. (a,b) Facial appearance of the P1 wild-type (a) and Hand1BP (b) mice. Hand1BP mutant (b) exhibits brachycephaly and eyelid colobomas (an arrowhead). (c-n) Alizarin red and alcian blue staining of P1 wild-type and Hand1BP mice, as indicated. The pterygoid bone (pt), basisphenoid bone (bs), and basioccipital bone (bo) of Hand1BP mutants are hypoplastic (h,j). Hypoplasia of the frontal bones (fb) and open frontal foramina (asterisk) are observed in the skull vault of Hand1BP mutant (n). li, lower incisor; ui, upper incisor; pmx, premaxilla; pt, pterygoid; lo, lamina obturans; ppmx, palatal process of maxilla; pppl, palatal process of palatine; vo, vomer; eo, exoccipital bone; agp, angular process; crp, coronoid process; cdp, condylar process; pb, parietal bone.

Altered expression of Hand1 partially recapitulates Hand2-induced skeletal patterning

We next examined whether the neural crest phenotype was specific for the Hand protein family. To test whether Hand1 also transforms the upper jaws to the lower jaws, we used Hand1CAT/+; Wnt1-Cre (hereafter Hand1NC) mice and examined the craniofacial phenotypes at P1. Hand1NC mutants resembled Hand2NC mutants with their brachycephaly and eyelid colobomas (Fig. 2Bb). Bone analysis of Hand1NC mutants revealed that the maxillary structures were hypoplastic and were replaced by a partially duplicated set of mandibular bones with mandibular molar alveoli (Fig. 2Bd,f; Supplementary Table S2). When we overexpressed Hand1 specifically in the osteochondral progenitors of the bone primordium, Hand1CAT/+; Twist2-Cre (hereafter Hand1BP) mutants showed similar but weak phenotypes (Fig. 3B) compared with Hand1NC mutants (Fig. 2B). Abnormalities were not observed in Hand1CAT/+ mice (n = 16).

The significance of the endoderm- and ectoderm-derived epithelium for craniofacial development has been demonstrated27,28. To examine the contribution of Hand transcription factors to the epithelial lineage in jaw development, we crossed Hand2 or Hand1 transgenic mice with the KRT14-Cre mice and examined the craniofacial phenotypes. The altered expression of the conditional alleles for Hand2 or Hand1 in the KRT14-Cre mice resulted in a lack of bone phenotypes at P1 (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). These data suggest that the Hand transcriptional factors exert specific functions in the NCCs and bone primordium to control the patterning of the jaws.

Hand2- and Hand1-induced mandibular transformations are accompanied by oral tissue remodeling

Lesser Hand2NC mutants than expected were obtained (Supplementary Table S1). To determine whether this was a consequence of decreased viability, we examined Hand2NC embryos. Until embryonic day (E) 12.5, the surface appearance of Hand2NC embryos was normal. At E13.5, Hand2NC mutants were characterised externally by inadequate pigmentation in the ventral retina (Supplementary Fig. S3). At E13.5–E16.5, Hand2NC mutants showed small pinna, brachycephaly, and tongue protrusion. In addition, Hand2NC mutants often exhibited exencephaly or hemorrhage (Supplementary Fig. S3).

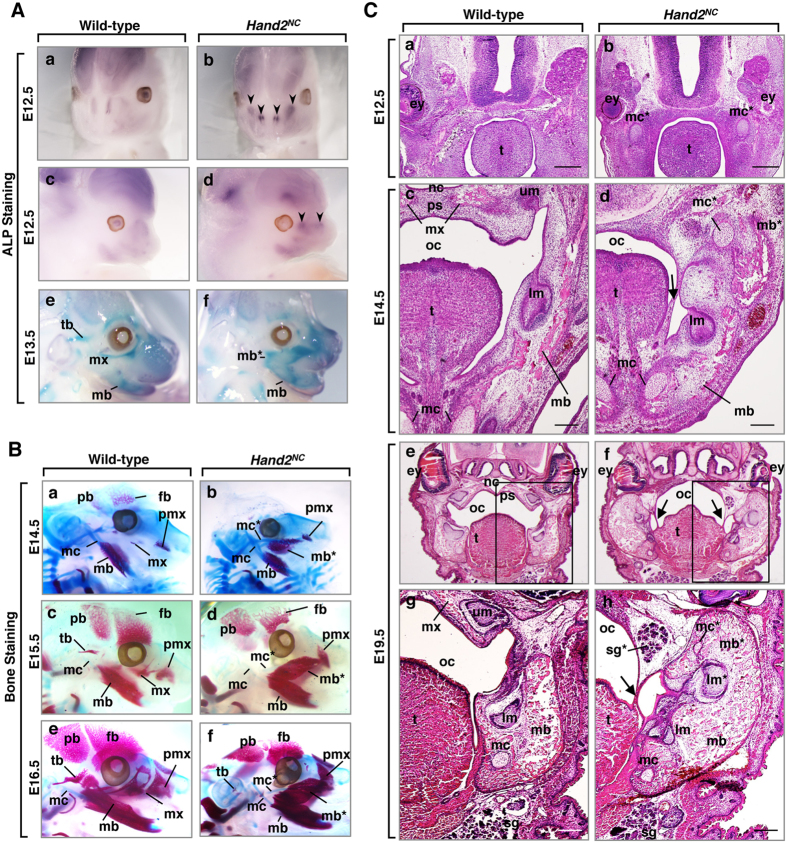

To analyse the effects of Hand2 on the mandibular bone patterning, we next examined jaw development of wild-type and Hand2NC embryos from E12.5 to E16.5. Altered expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), an early osteoblast marker, was observed in the maxillary process of Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 4Ab,d), suggesting that the destination of the maxillary arch was determined as early as E12.5. The duplicated mandible in the maxillary region was confirmed in whole-mount ALP staining of Hand2NC mutants at E13.5 (Fig. 4Af). Bone staining of embryos showed that the maxillary bone was aplastic, the premaxilla was deformed, and the duplicated mandible contained ectopic truncated Meckel’s cartilage in the maxillary region of Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 4Bb,d,f). Ossification of the temporal bones was delayed in Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 4Bb,d,f).

Figure 4. Morphological transformation of the maxillary to mandibular process in Hand2NC mutants.

(A) Whole-mount alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining of E12.5 (a–d) and E13.5 (e,f) wild-type (a,c,e) and Hand2NC (b,d,f) embryos. The arrowheads indicate the changes in ALP expression (b,d). (B) Skeletal preparations at E14.5 (a,b), E15.5 (c,d), and E16.5 (e,f) from wild-type (a,c,e) and Hand2NC (b,d,f) embryos. The mutant maxilla (mx) is transformed to duplicated mandibular bone primordium (mb*) and is associated with the duplicated Meckel’s cartilage (mc*). The delayed ossification of the temporal bones (tb) and fontal bones (fb) are observed in Hand2NC mutants (b,d,f). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained coronal sections of E12.5 (a,b), E14.5 (c,d), and E19.5 (e–h) wild-type (a,c,e,g) and Hand2NC (b,d,f,h) heads. In Hand2NC mutants, duplicated Meckel’s cartilages (mc*) are observed in the maxillary region (b,d,h). The palatal shelves (ps) are missing, and the original mandible is fused to the duplicated mandible by connective tissue strings (arrows in d,f,h). At E19.5, Hand2NC mutants exhibit ectopic salivary glands (sg*) in the maxillary region and a second set of lower molars (lm*) in the duplicated mandible (mb*) (h). Scale bars: 300 μm (a,b), 200 μm (c,d,g,h). mx, maxilla; mb, mandibular bone; tb, temporal bone; mc, Meckel’s cartilage; fb, frontal bone; pb, parietal bone; pmx, premaxilla; ey, eye; oc, oral cavity; sg, salivary glands; lm, lower molar; um, upper molar; t, tongue. An asterisk indicates a duplicate.

To further examine the role of Hand2 in jaw development, we performed histological analysis of Hand2NC mutants. At E12.5, ectopic Meckel’s cartilage was observed in the maxillary region of Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 4Cb). At E14.5, the control palatal shelves were elevated above the dorsum of the tongue and fused at the midline (Fig. 4Cc), whereas the palatal shelves of Hand2NC mutants were missing, and the duplicated mandible was fused to the original mandible by connective tissue strings (Fig. 4Cd). At E19.5, heads of Hand2NC mutants showed duplication of the mandibular bone and Meckel’s cartilage, ectopic salivary glands in the maxillary region, and a second set of lower molars in the duplicated mandible (Fig. 4Ch). Hand1NC mutants (Supplementary Fig. S4) were histologically similar to Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 4C). These results revealed that Hand proteins determine the mandibular identity and that correct Hand expression is required in the mandibular arch for normal palatogenesis to occur.

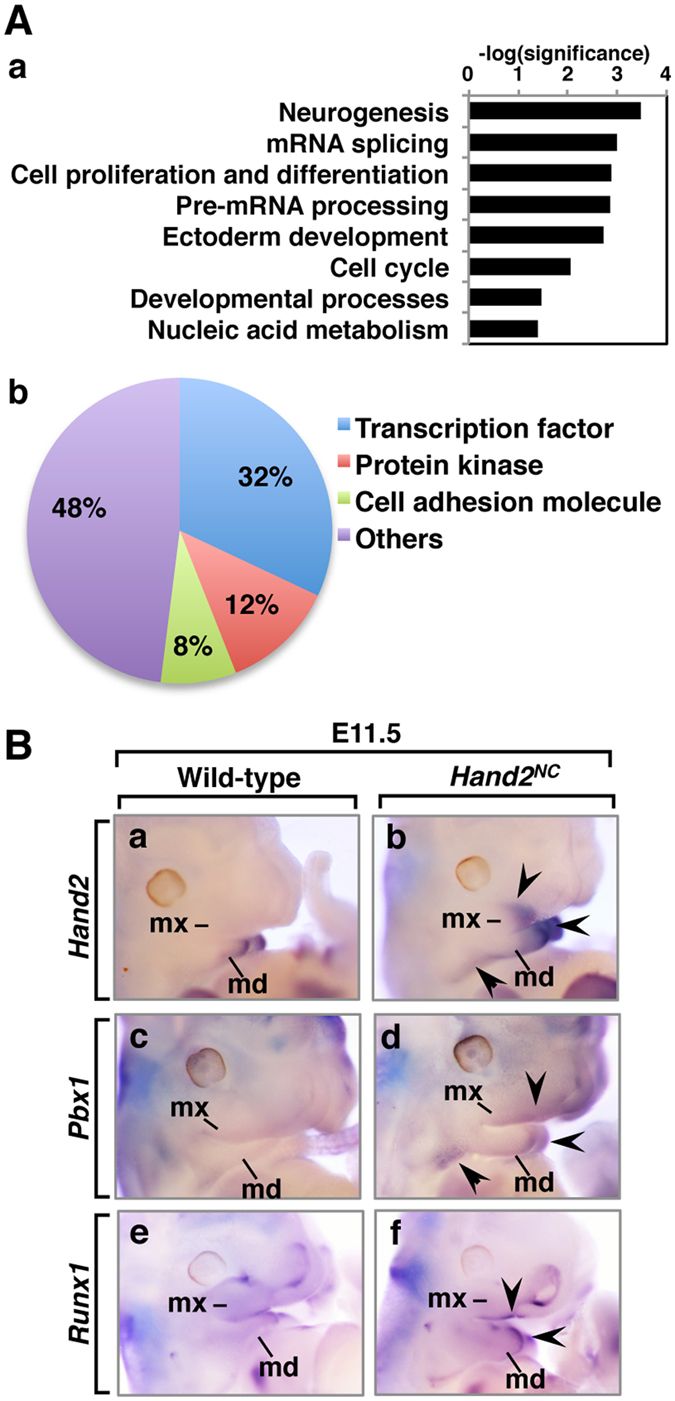

Hand2 controls expression of Pbx1 and Runx1 in the first branchial arch

The maxilla-to-mandible transformation of the first branchial arch in Hand2NC mutants indicated that altered Hand2 expression converted the genetic program from the maxillary to the mandibular arch. To further determine the downstream genes of Hand2, we performed gene expression profiling on E11.5 Hand2NC embryos. Surprisingly, only a small portion of the genes was dysregulated in E11.5 Hand2NCmutants; 51 genes were downregulated, and 17 genes, including the Hand2 gene, were upregulated when the two-fold change cutoff was applied (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). To analyse whether certain molecular functions or biological processes were sensitive to the altered Hand2 expression in the neural crest, a gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed on the dysregulated genes. Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER)29 indicated that the prominent biological process was neurogenesis (Fig. 5Aa). The genes that were dysregulated in the developmental processes were further analysed for their annotated molecular function. The majority of the dysregulated genes encoded transcription factors (Fig. 5Ab, Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 5. Aberrant gene expression resulting from the altered expression of Hand2.

(A) Affinity GeneChip array analysis of wild-type and Hand2NC heads at E11.5. Gene ontology analysis was performed with the PANTHER classification system (n = 4 per genotype). (a) Significantly (P < 0.05) enriched biological processes are shown. (b) The prominent molecular function in the developmental processes is the transcription factor (P = 0.00016). (B) The expression patterns of the genes that are upregulated in the Hand2NC maxillary and mandibular processes at E11.5. Lateral views of wild-type (a,c,e) and Hand2NC (b,d,f) embryos that were processed by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Arrowheads indicate changes in gene expression. md, mandibular arch; mx, maxillary arch.

To understand the transcriptional network controlled by Hand2, we examined the dysregulated expression of the transcription factors in E11.5 embryos. In Hand2NCmutants, levels of Hand2 and Pbx1 expression were increased in the medial mandibular process and hyoid arch, and the altered expression of these genes was observed in the maxillary process (Fig. 5Bb,d). The Runx1 expression was also increased in the medial mandibular process and maxillomandibular junction in Hand2NCmutants (Fig. 5Bf). Analysis of the expression of Hif1a, Rsf1, Six4, Rb1cc1, Sfmbt2, and Dner did not reveal any obvious differences between the wild-type and Hand2NCheads (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Hand2 activates a mandible-specific genetic program in the maxillary process

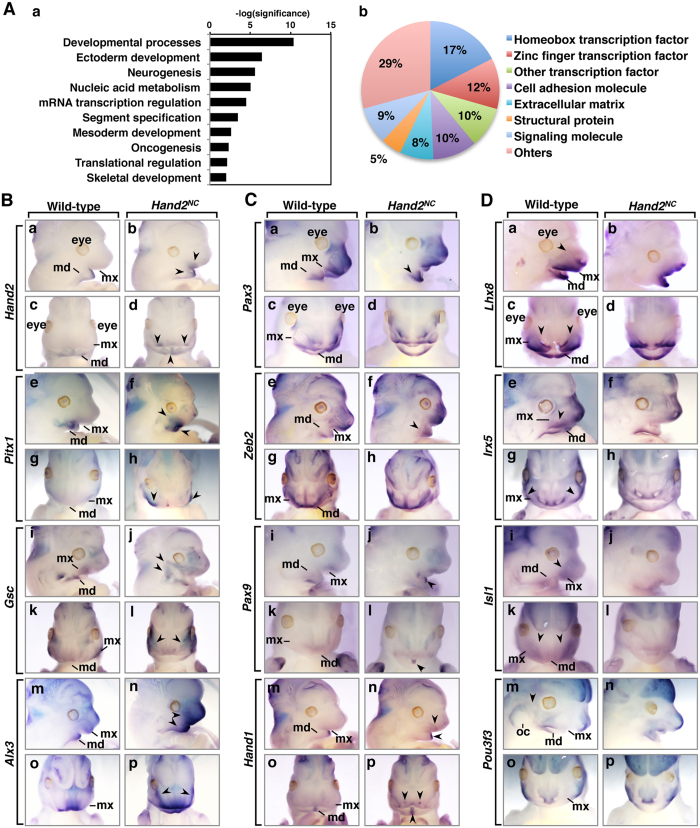

Hand2 gene expression was confirmed in the mandibular region at E12.5 (Fig. 1B) and Hand2NCmutants were first recognised by dysmorphogenesis of the head at E12.5 (Fig. 4C). To find downstream genes of Hand2, we next performed a microarray analysis using the heads from E12.5 embryos. We found that 61 genes, including the Hand2 gene, were upregulated, and 84 genes were downregulated, with a cutoff of a two-fold change (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). Interestingly, the expression of Smr2, a member of the gene family encoding salivary glutamine/glutamic acid-rich proteins, was upregulated in Hand2NC mutant heads at E12.5 (Supplementary Table S7). A gene ontology analysis showed that the most significantly enriched biological process in the E12.5 Hand2NC mutants was the developmental processes (Fig. 6Aa). The prominent molecule was transcription factors, especially the homeobox transcription factor (Fig. 6Ab). Most dysregulated homeobox transcription factors have been linked to human genetic diseases or genetically engineered mice with craniofacial anomalies (Supplementary Table S8).

Figure 6. Hand2-regulated expression of homeobox transcription factors.

(A) Affinity GeneChip array analysis of wild-type and Hand2NC heads at E12.5 (n = 3 per genotype). Gene ontology analysis was performed with the PANTHER classification system. (a) Significantly (P < 0.05) enriched biological processes are shown. (b) The prominent molecular function in the developmental processes is the homeobox transcription factor (P = 8.1 × 10−17). (B–D) The expression patterns of the genes that are dysregulated in the Hand2NC maxillary and mandibular processes at E12.5. Lateral (upper panels) and frontal (lower panels) views of wild-type and Hand2NC embryos processed by whole-mount in situ hybridization, as indicated. Arrowheads indicate the changes in gene expression. md, mandibular process; mx, maxillary process; oc, otic capsule.

The patterning of cranial and branchial NCCs is achieved by the regulation of homeobox transcription factors. To better understand the transcriptional network that is controlled by Hand2 during jaw patterning, we focused on the homeobox transcription factors that had altered regulation in Hand2NCmutants. Whole-mount in situ hybridization showed that Hand2 was only expressed in the mandibular process of wild-type embryos, whereas ectopic Hand2 expression was observed in the lateral region of the maxillary process in Hand2NC mutants at E12.5 (Fig. 6B). The ectopic expression of Pitx1 was also confirmed in the maxillary process and increased in the mandibular process of Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 6B). Gsc expression is downregulated in the branchial arches of hand2 mutant zebrafish hanS6 and conditional Hand2 knockout mice30,31. In Hand2NC mutants, Gsc was ectopically expressed, suggesting that Hand2 maintains or activates Gsc expression in the branchial arches. Alx3 expression was increased in the mandibular and maxillary processes (Fig. 6B). The levels of expression of Pax3 and Zeb2 were increased in the mandibular process of Hand2NC mutants (Fig. 6C). We have shown that the ablation of Hand1 and Hand2 in the NCCs affects the expression of Pax9 in the distal midline of the mandibular process10. In Hand2NC mutants, the levels of Pax9 expression were increased in the midline of the mandibular process where Hand2 expression was highly upregulated by the transgene (Fig. 6C). The expression of Lhx8, as well as Isl1, which is required for establishing the posterior hind limb field upstream of the Hand2-Shh pathway32, was less intense in the maxillary process of Hand2NC mutants, while the expression of these genes was not affected in the mandibular process (Fig. 6D). Similarly, the expression of Irx5, which has been identified as a direct target of Hand2 in limb buds24, was reduced in the maxillary process (Fig. 6D). Pou3f3 is required for the formation of maxillary components, including the temporal bone, jaw joint, and incus33. Consistent with the bone phenotype of Hand2NCmutants (Fig. 2A,C), Pou3f3 expression was absent at the maxillary-mandibular junction in Hand2NCmutants (Fig. 6D). Because Hand2 regulates Hand1 expression in the mandibular arch31, we examined Hand1 expression in Hand2NC mutants. Ectopic Hand1 expression in the maxillary process of Hand2NC mutants was confirmed in the lateral region, although the expression level appeared lower than that in the midline of the mandibular process (Fig. 6C). The expression of Zfhx3, Hmx1, and Shox2 was not obviously different in the mandibular and maxillary processes of wild-type and Hand2NC mutants (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Oral functional registration of the palate requires the correct integration of the secondary palate of the maxillary process and the primary palate. For simultaneous breathing and feeding, palate formation between the oral and nasal cavities must be appropriately aligned. Cleft palate is the most frequent congenital anomaly in humans34. Altered Hand2 gene expression in the maxillary arch results in a loss of the secondary palate and nasal cavities (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the dysregulated genes in Hand2NC mutants are involved in palatogenesis. Whole-mount in situ hybridization of the E12.5 embryos also showed that Alx3, Lhx8, Pax3, Pitx1, Shox2, Gsc, Zeb2, Isl1, Rhox4b, Uncx, and Hmx1 were expressed in the secondary palate (Supplementary Fig. S6), suggesting that these homeobox transcription factors may be implicated in palatal development as intrinsic factors. Among these genes, ablation or mutation of Alx3, Lhx8, Pax3, Pitx1, Shox2, and Zeb2 induces cleft palates in humans and/or mice (Supplementary Table S8). Collectively, these results indicate that NCCs within the first branchial arches respond to Hand2 transcription activity, which controls jaw patterning and palatogenesis by regulating the expression of homeobox transcription factors (Fig. 7).

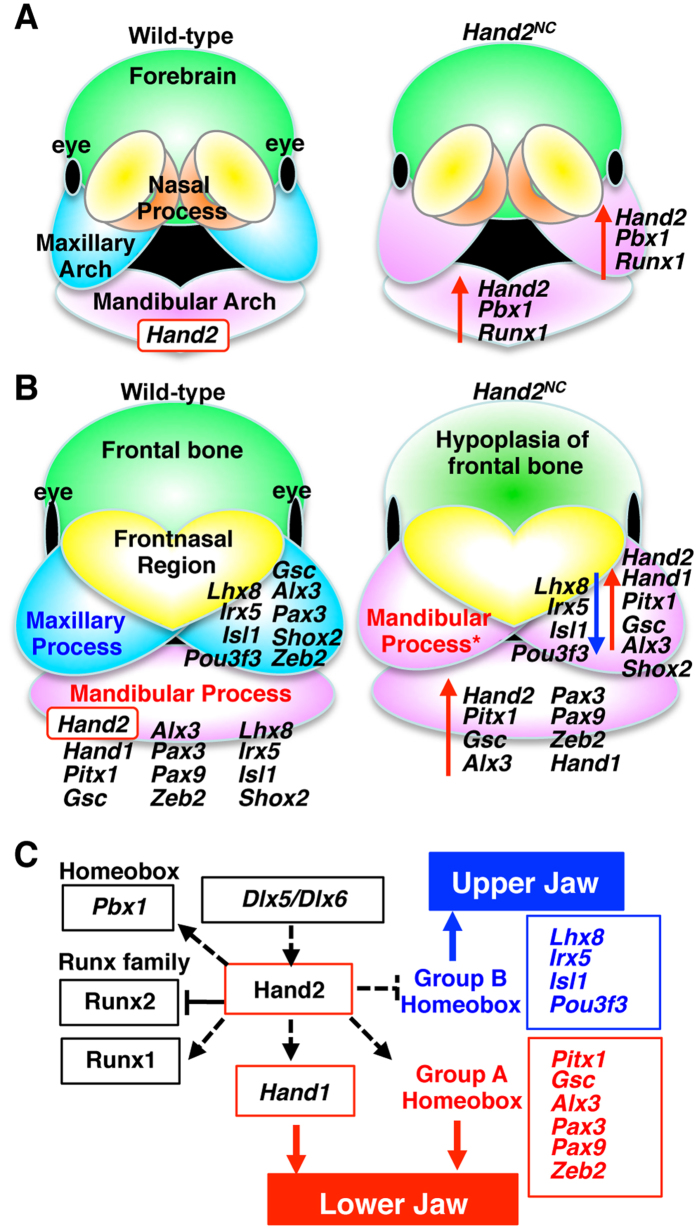

Figure 7. The putative networks governed by Hand2 in the branchial arch.

(A,B) Schematic presentation of the transcription factor expression that is affected by altered Hand2 expression in the neural crest-derived cells at E11.5 (A) and E12.5 (B). The red arrows indicate upregulation, and the blue arrow indicates downregulation in the Hand2NC mutants compared with the wild-type. The nested expression of Hand2 in the mandibular process regulates jaw patterning by controlling the homeobox transcription factors. An asterisk indicates a duplicate. (C) Model of the putative transcriptional regulation of mandibular identity by Hand2. Dlx5 and Dlx6 activate Hand2 expression distally15,16,33. Hand2 induces and/or maintains Group A and represses Group B homeobox transcription factors in the mandibular process. Presumably, the Group A homeobox transcription factors are involved in lower jaw identity, whereas the Group B homeobox transcription factors promote upper jaw development. The solid lines indicate direct interactions, whereas the dashed lines indicate genetic interactions.

Discussion

The bHLH transcription factor Hand2 is expressed in NCCs in the mandibular arch but not in the maxillary arch of the first branchial arch. The Hand2 sequence is conserved among jawed vertebrates but not among jawless vertebrates. Consistent with its expression pattern and amino-acid alignment, Hand2 gene expression is incompatible with maxillary jaw development, and altered Hand2 expression transforms the maxilla to the mandible and controls the specification of jaw identity. Hand2 orchestrates the dynamics of transcription factors and regulates the patterning of the first branchial arch (Fig. 7), suggesting that its role as one of the central molecules that determine the dorsoventral polarity of the first branchial arch. The skeletal abnormalities of Hand2NCmutants were similar to those seen in EdnraHand2/+ mutants19 except for the penetration. However, we cannot formally rule out the possibility that overexpression of Hand2 may lead to changes that are not physiological and that are not representative of the true function or network of Hand2.

Regulation of jaw patterning and bone formation by Hand2

The functional modification of genes has been causally linked to adaptive evolution. The Hand2 amino sequence is evolutionally conserved in jawed vertebrates but less conserved in jawless vertebrates and invertebrates. In particular, the N-terminus of Hand2 is only conserved among jawed vertebrates, suggesting that the domain may contribute to the acquisition of the hinged jaw and the evolution from jawless to jawed vertebrates. We have shown that the N-terminus of Hand2 has an anti-osteogenic function by directly inhibiting Runx211. Interestingly, hand2 zebrafish mutant hanc99, which lacks a region equivalent to the N-terminal amino acids (1–53aa) of mouse Hand2, has defects in jaw development and exhibits continuous upper jaw joints35,36. Since Hand proteins can dimerise with bHLH proteins to form a bipartite DNA-binding domain that recognises the E-box element23,37,38, the overexpression of Hand proteins may alter the dimerization pool of bHLH transcription factors or the DNA-binding activity in the branchial arch. The expression patterns of hand in the branchial arches of lampreys are similar to those of orthologous hand genes in jawed vertebrates22, even though the number of Hand orthologs expressed in the branchial arches of jawless and jawed vertebrates may be different. Multiple-species sequence alignment and expression analysis of Hand2 target molecules may yield insights into vertebrate evolution.

Transformation of the upper jaw into the lower jaw is observed in Edn1 knock-in mice (EdnraEdn1/+), in which one copy of Edn1 was knocked into the Ednra locus, resulting in constitutive Ednra activation19. The effects of constitutive Ednra activation are mostly restricted to the first branchial arch, even though Ednra expression occurs throughout the head and branchial arches19. In EdnraEdn1/+ mice, the complete mandibular bones with continuous Meckel’s cartilage and malleus were duplicated. In Hand2NC mutants, the duplicated dentary was complete with the angular process, but the condylar process, coronoid process, and malleus were aplastic or hypomorphic in the duplicated mandible, suggesting that Hand2 is involved in the formation of the dentary and angular process of the mandibular bone. In the maxillary region of Hand2NC mutants, the presphenoid, vomer, and palatal bones were missing, and they were replaced by mandibular elements, whereas these maxillary elements remained in EdnraEdn1/+ mice. It is possible that the constitutive Ednra activation predominantly affects the first branchial arch in EdnraEdn1/+ mice, whereas the expression of Hand2 is altered in the cranial NCCs in Hand2NCmice. Other explanations are that part of the Hand2 expression is independent from Ednra1/Edn1-Dlx5/6 signalling17,19.

The altered expression of Hand2 in the cranial NCC-derived bone primordium resulted in hypoplastic bone formation in the cranial region, and this was observed in the frontal bones, temporal bones, and dorsal mandibular elements. Altered Hand2 expression in the bone primordium (Hand2BP) resulted in the aplasia of the basioccipital bones. These results indicate that Hand2 antagonises the genetic program for the formation of membranous bones and are consistent with the findings that Hand2 negatively regulates the ossification of the mandibular bone by directly inhibiting Runx2, which is a master transcription factor of osteoblast-specific genes11. In contrast, the response of the NCCs in the second branchial arch to the altered Hand2 expression was limited, suggesting that the levels of Hand2 expression were not critical in the second branchial arch. Because the targeted deletion of Hoxa2 transforms the second branchial arch to a mandibular branchial arch39, Hox genes may be primarily involved in determining the patterning of the second branchial arch. Thus, the Hand2 expression levels and domains must be exquisitely regulated for the bone formation of the first branchial arch.

Regulation of gene expression by Hand2

The present studies demonstrate that a number of genes are disrupted following the Hand2 overexpression, subsequently inducing the maxilla-to-mandible transformation. The transformation induced a mirror-image duplication, suggesting that positional information along the maxillary-mandibular axis is present. Runx1, which is expressed in the maxillomandibular junction of the first branchial arch, may function as one of the patterning molecules. Interestingly, some of the dysregulated genes in the E11.5 Hand2NC mice are involved in the transformation of elements. In Pbx1-deficient mice, the NCC-derived bones of the second branchial arch were morphologically transformed into elements that were reminiscent of first arch-derived cartilage40. In Hoxc8-deficient mice, several skeletal segments were transformed into the likeness of more anterior ones41. At E12.5, Hand2-mediated signalling positively regulated the mandibular-specific expression of Pitx1, Gsc, Alx3, Zeb2, and Pax9 and influenced the repression of Lhx8, Irx5, Isl1, and Pou3f3 genes in the mandibular arch. Osterwalder et al. (2014) identified a set of Hand2-target regions in mouse embryonic tissues with Hand2 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR analysis24, and showed that Hand2 chromatin complexes were enriched in the genomic landscape of the following transcription regulators: Pbx1, Pitx1, Gsc, Alx3, Shox2, Pax3, Zeb2, Pax9, Lhx8, Irx5, Isl1, Pou3f3, and Hand1 (Gene Expression Omnibus #GSE55707). Hand2 may directly regulate some of the transcription factors that participate in craniofacial development. The premaxilla of Hand2NC mutants remained with upper incisors, and the ectopic induction of transcription factors was not observed in the midline of the maxillary process, suggesting that the effects of Hand2 were restricted to the maxillary prominences, except in the FNP. In Hand2NC mutants, the environmental signals from the FNP ectodermal zone may competently respond to Hand2 signalling.

Implications for human diseases

The homeobox transcription factors with altered regulation in Hand2NC mutants are also important in the etiology of the Mendelian forms of syndromes. Alx3, Gsc, Pax3, Pax9, Pitx1, and Zeb2, the expression of which was positively regulated by Hand2-mediated signalling, are the disease genes of craniofacial syndromes (Supplementary Table S8). Among the craniofacial syndromes, auriculocondylar syndrome [Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) #602483 and #614669] is characterised by outer ear and mandible malformations that affect NCC development within the first and second branchial arches. Recent studies have found that patients with auriculocondylar syndrome have mutations in the genes, EDN1, EDNRA1, PLCB4 and GNAI3, which function in the endothelin signalling pathway42,43,44; however, mutations in HAND2 have not been identified in patients with auriculocondylar syndrome. Since the homeobox transcription factors with altered regulation in Hand2NC mutants were also expressed in the palatal shelves, the mutations in genes downstream of Hand2 could also be associated with craniofacial syndromes with mandibular and/or palatal anomalies.

In summary, our analysis reveals that altered Hand2 expression in the maxillary arch results in altered homeobox transcription factor regulation in the mandibular and maxillary processes and a transformation of the upper jaw into the lower jaw. The results of the present study also suggest that nested Hand2 expression in the mandibular arch is necessary for palatogenesis. Hand2 and Hand1 genes might have had a central role in the coordination of oral morphogenesis that diverted the craniofacial shape noted in vertebrates and the transition between filter feeding and active predation by providing specific mandibular identity. Moreover, the modification of the Hand2 sequence may contain a specific code that contributed to the transition from jawless to jawed vertebrates. Integration of the molecular data will enhance the understanding of the morphogenetic program for mandibular and maxillary patterning.

Methods

Generation of Hand2 and Hand1-mutant mice

The transgene vectors CAG-lox-CAT-lox-Hand2-polyA and CAG-lox-CAT-lox-Hand1-polyA were constructed and injected into fertilised eggs to generate the permanent transgenic lines CAG-CAT Hand2Tg/+ (Stock No. RBRC01366, RIKEN, Wako, Saitama, Japan) and CAG-CAT Hand1Tg/+ (Stock No. RBRC01369, RIKEN), respectively. Hand2-LacZ45, Wnt1-Cre46 (Stock No. 7807, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), Twist2-Cre knock-in26,47 (Stock No. 8712, The Jackson Laboratory), and KRT14-Cre48 (Stock No. 4782, The Jackson Laboratory) mice have been previously described. For the conditional activation of Hand2 or Hand1, we generated double-transgenic mice by intercrossing CAG-floxed CAT-Hand2 or -Hand1 with Wnt1-Cre, Twist2-Cre, or KRT14-Cre mice. Wild-type littermates were used as controls. All of the animal experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Permit Number: 0160215A). All experiments were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Histology and in situ hybridization

The embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate buffered saline and embedded in paraffin. The sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E). Whole-mount and section in situ hybridization was performed as described previously11,28. A probe for Hand1 was generously provided by Eric N. Olson49. Other probes were prepared by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. RT-PCR was performed as described previously50. The primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S9.

Ortholog identification

The Hand2 protein sequences of the following 10 vertebrates and 2 invertebrates were downloaded from the Ensembl Genome Browser (http://asia.ensembl.org/index.html): human, mouse, chicken, zebra finch, Xenopus tropicalis, medaka, stickleback, Tetraodon, cod, zebrafish, fruit fly, and Caenorhabditis elegans. The elephant shark proteome was obtained from the Elephant Shark Genome Project (http://esharkgenome.imcb.a-star.edu.sg)5. To identify the ortholog of the lamprey, a protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was run with default settings from the Japanese Lamprey Genome Project (http://jlampreygenome.imcb.a-star.edu.sg). The BLAST analysis of the amino-acid sequences of the mouse Hand proteins against the entire lamprey genome revealed no appreciable identity to any of the sequences except for JL1799. ClustalW (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw) and Ensembl were used to create multiple sequence alignments of Hand2 and the rooted phylogenetic trees of the Hand proteins.

Skeletal staining, β-galactosidase staining, and whole-mount ALP staining

Alizarin red and alcian blue staining, β-galactosidase staining, and whole-mount ALP staining were performed as described previously11,28. The representative pictures from each group (n = 3) were shown.

Microarray and gene ontology analysis

Total RNA was extracted either from wild-type or Hand2NC embryos with TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and a RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and subsequently pooled prior to analysis. For each RNA sample, the concentration and purity were measured with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrometer, and the quality was then checked with 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The microarray analysis was performed by the KURABO Bio-Medical Department with the GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). A gene ontology analysis was performed with the PANTHER database (http://pantherdb.org). Only biological processes with significant (P < 0.05) enrichment were used to examine molecular function. To elucidate the molecular pathogenesis of genes, genetic diseases in humans and genetically engineered mice were investigated with the OMIM program (http://omim.org) and Mouse Genome Informatics program (http://www.informatics.jax.org), respectively.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Funato, N. et al. Specification of jaw identity by the Hand2 transcription factor. Sci. Rep. 6, 28405; doi: 10.1038/srep28405 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank James A. Richardson, John Shelton, and Jesse A. Morris of the Molecular Pathology Core Laboratory at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for performing the section in situ hybridizations and Eriko Matsumoto for her technical assistance. In addition, we thank David Rowitch, David Ornitz, Andrew McMahon, Eric N. Olson, and Rhonda Bassel-Duby for mice and reagents. N.F. was a recipient of a grant provided by the JSPS KAKENHI (25670774, 15K11004).

Footnotes

Author Contributions N.F., H.Y. and Y.S. designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the paper; N.F., K.H. and M.N. performed the experiments for mice. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

References

- Oisi Y., Ota K. G., Kuraku S., Fujimoto S. & Kuratani S. Craniofacial development of hagfishes and the evolution of vertebrates. Nature 493, 175–180 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota K. G., Kuraku S. & Kuratani S. Hagfish embryology with reference to the evolution of the neural crest. Nature 446, 672–675 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetani Y. et al. Heterotopic shift of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in vertebrate jaw evolution. Science 296, 1316–1319 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depew M. J., Lufkin T. & Rubenstein J. L. Specification of jaw subdivisions by Dlx genes. Science 298, 381–385 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B. et al. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 505, 174–179 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn M. J. Evolutionary biology: lamprey Hox genes and the origin of jaws. Nature 416, 386–387 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. J. et al. Sequencing of the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) genome provides insights into vertebrate evolution. Nat. Genet. 45, 415–421(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor P. A. Specification of neural crest cell formation and migration in mouse embryos. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 683–693 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa H., Clouthier D. E., Richardson J. A., Charite J. & Olson E. N. Targeted deletion of a branchial arch-specific enhancer reveals a role of dHAND in craniofacial development. Development 130, 1069–1078 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa A. C. et al. Hand transcription factors cooperatively regulate development of the distal midline mesenchyme. Dev. Biol. 310, 154–168 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato N. et al. Hand2 controls osteoblast differentiation in the branchial arch by inhibiting DNA binding of Runx2. Development 136, 615–625 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor P. A. & Krumlauf R. Hox genes, neural crest cells and branchial arch patterning. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 698–705 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santagati F. & Rijli F. M. Cranial neural crest and the building of the vertebrate head. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 806–818 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis J. A., Modrell M. S. & Baker C. V. Developmental evidence for serial homology of the vertebrate jaw and gill arch skeleton. Nat. Commun. 4, 1436 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava D. et al. Regulation of cardiac mesodermal and neural crest development by the bHLH transcription factor, dHAND. Nat. Genet. 16, 154–160 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charite J. et al. Role of Dlx6 in regulation of an endothelin-1-dependent, dHAND branchial arch enhancer. Genes Dev. 15, 3039–3049 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruest L. B., Xiang X., Lim K. C., Levi G. & Clouthier D. E. Endothelin-A receptor-dependent and -independent signaling pathways in establishing mandibular identity. Development 131, 4413–4423 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T. et al. Developmental genetic bases behind the independent origin of the tympanic membrane in mammals and diapsids. Nat. Commun. 6, 6853 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T. et al. An endothelin-1 switch specifies maxillomandibular identity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18806–18811 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares A. L. & Clouthier D. E. Cre recombinase-regulated Endothelin1 transgenic mouse lines: novel tools for analysis of embryonic and adult disorders. Dev. Biol. 400, 191–201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takio Y. et al. Evolutionary biology: lamprey Hox genes and the evolution of jaws. Nature 429, 262–263 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny R. et al. Evidence for the prepattern/cooption model of vertebrate jaw evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17262–17267 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. G., McAnally J., Richardson J. A., Charite J. & Olson E. N. Misexpression of dHAND induces ectopic digits in the developing limb bud in the absence of direct DNA binding. Development 129, 3077–3088 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder M. et al. HAND2 Targets Define a Network of Transcriptional Regulators that Compartmentalize the Early Limb Bud Mesenchyme. Dev. Cell 31, 345–357 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor P. A., Melton K. R. & Manzanares M. Origins and plasticity of neural crest cells and their roles in jaw and craniofacial evolution. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 47, 541–553 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K. et al. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development 130, 3063–3074 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Marcucio R. S. & Helms J. A. A zone of frontonasal ectoderm regulates patterning and growth in the face. Development 130, 1749–1758 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato N., Nakamura M., Richardson J. A., Srivastava D. & Yanagisawa H. Tbx1 regulates oral epithelial adhesion and palatal development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 2524–2537 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H., Muruganujan A. & Thomas P. D. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D377–D386 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. T., Schilling T. F., Lee K., Parker J. & Kimmel C. B. sucker encodes a zebrafish Endothelin-1 required for ventral pharyngeal arch development. Development 127, 3815–3828 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron F. et al. Downregulation of Dlx5 and Dlx6 expression by Hand2 is essential for initiation of tongue morphogenesis. Development 138, 2249–2259 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itou J. et al. Islet1 regulates establishment of the posterior hindlimb field upstream of the Hand2-Shh morphoregulatory gene network in mouse embryos. Development 139, 1620–1629 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. et al. Dlx genes pattern mammalian jaw primordium by regulating both lower jaw-specific and upper jaw-specific genetic programs. Development 135, 2905–2916 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolarova M. M. & Cervenka J. Classification and birth prevalence of orofacial clefts. Am. J. Med. Genet. 75, 126–137 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelon D. et al. The bHLH transcription factor hand2 plays parallel roles in zebrafish heart and pectoral fin development. Development 127, 2573–2582 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. T., Yelon D., Stainier D. Y. & Kimmel C. B. Two endothelin 1 effectors, hand2 and bapx1, pattern ventral pharyngeal cartilage and the jaw joint. Development 130, 1353–1365 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firulli B. A., Hadzic D. B., McDaid J. R. & Firulli A. B. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors dHAND and eHAND exhibit dimerization characteristics that suggest complex regulation of function. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33567–33573 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. S. & Cserjesi P. The basic helix-loop-helix factor, HAND2, functions as a transcriptional activator by binding to E-boxes as a heterodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 12604–12612 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santagati F., Minoux M., Ren S. Y. & Rijli F. M. Temporal requirement of Hoxa2 in cranial neural crest skeletal morphogenesis. Development 132, 4927–4936 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selleri L. et al. Requirement for Pbx1 in skeletal patterning and programming chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Development 128, 3543–3557 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Mouellic H., Lallemand Y. & Brulet P. Homeosis in the mouse induced by a null mutation in the Hox-3.1 gene. Cell 69, 251–264 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder M. J. et al. A human homeotic transformation resulting from mutations in PLCB4 and GNAI3 causes auriculocondylar syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 907–914 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C. T. et al. Mutations in endothelin 1 cause recessive auriculocondylar syndrome and dominant isolated question-mark ears. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 1118–1125 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C. T. et al. Mutations in the endothelin receptor type A cause mandibulofacial dysostosis with alopecia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 519–531 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. G. et al. A GATA-dependent right ventricular enhancer controls dHAND transcription in the developing heart. Development 127, 5331–5341 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielian P. S., Muccino D., Rowitch D. H., Michael S. K. & McMahon A. P. Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Curr. Biol. 8, 1323–1326 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosic D., Richardson J. A., Yu K., Ornitz D. M. & Olson E. N. Twist regulates cytokine gene expression through a negative feedback loop that represses NF-kappaB activity. Cell 112, 169–180 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassule H. R., Lewis P., Bei M., Maas R. & McMahon A. P. Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development 127, 4775–4785 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. G. et al. The Hand1 and Hand2 transcription factors regulate expansion of the embryonic cardiac ventricles in a gene dosage-dependent manner. Development 132, 189–201 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato N., Nakamura M., Richardson J. A., Srivastava D. & Yanagisawa H. Loss of Tbx1 induces bone phenotypes similar to cleidocranial dysplasia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 424–435 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.