Abstract

Objectives

Studies have shown that dentists have a higher incidence of work-related musculoskeletal (MSK) pain than those in other occupations. The risk factors contributing to MSK pain among Saudi dentists has not been fully studied so this study aims to estimate the prevalence of MSK pain and investigate its associated risk factors among dentists in Saudi Arabia.

Setting and participants

A cross-sectional survey was carried out in the capital city Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, using random cluster sampling. 224 surveys were distributed among dentists with a 91.1% response rate (101 women and 103 men).

Outcomes

The prevalence of MSK pain and its associated risk factors were investigated.

Results

184 (90.2%) respondents reported having MSK pain. Lower back pain was the most commonly reported MSK pain (68.1%). Gender and age were reported to be predictors for at least one type of MSK pain. Older age was associated with lower back pain (OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.50) and women had double the risk of shoulder pain (OR 2.52; 95% CI 1.12 to 5.68). In addition, lower back pain was related to the time the dentist spent with patients (OR 0.28; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.54), while shoulder pain (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06) and lower back pain (OR 1.06; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.10) were significantly related to years of experience.

Conclusions

MSK pain is common among older and female Saudi dentists. Research on the impact of exercise and the ergonomics of the workplace on the intensity of MSK pain and the timing of its onset is required.

Keywords: musculoskeletal symptoms, work-related, risk factors, dental setting, dental ergonomics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge this is the first study in Riyadh to employ cluster random sampling.

A variety of dental personnel were surveyed.

Age, gender, marital status, specialty and poor workplace ergonomics contribute to musculoskeletal (MSK) pain in Saudi dentists.

Larger controlled studies are needed to further identify risk factors associated with MSK among dentists.

Further studies on dental training and ergonomics are encouraged.

Introduction

Dentistry is an expanding profession in Saudi Arabia. According the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties there were 5946 Saudi dentists in 2015, comprising 32% of all dentists working in Saudi Arabia. Musculoskeletal (MSK) pain is a major occupational health concern in dentistry.1 The higher rates of MSK pain among dentists can be attributed to various physiological and ergonomic factors related to the profession.2 Work-related factors include awkward postures and movements, frequent and prolonged use of vibrating tools, and time spent with each patient.3 Additional factors include the dentists body mass index (BMI), lengthy working hours, number of walk-in patients and number of scheduled patients per day.4 5 The frequency of awkward movements performed by dentists such as stooping, slouching, ducking, uncomfortable posture while sitting, and bending forwards and sideways for better manoeuvrability make dentists more prone to MSK pain.2 6 Such prolonged and awkward postures mostly affect the back, neck and upper extremities.2 6 MSK pain affects the quality of life of the dentist and may lead them to change profession to protect their health.7–9

Lower back pain is common among dentists. Its prevalence was reported to be around 37% in a study from Surat, India, which revealed that mental health, gender and exercise play a vital role in the development of MSK pain.10 A study of dentists carried out in New Zealand showed a prevalence of lower back pain of 54%, a prevalence of neck pain of 57% and a prevalence of shoulder pain of 52%.11 A study from Saudi Arabia in 2001 demonstrated that dentists reported reduced visibility of the mouths of their patients and restricted movement due to lack of work space.12 The study also reported that 55% of the sample population had neck pain while 74% had lower back pain that could potentially have been reduced by exercise. A more recent study in 2015 among dentists in Saudi Arabia showed that 85% have work-related MSK pain.13 However, the study had major limitations. First, it reported on only 225 members of one dental association and included dental assistants, dental hygienists and dental technicians, which is not considered representative of the total dental population. A further limitation is that questionnaire validation was not described.

The present study aims to estimate the prevalence of MSK pain among Saudi dentists and identify common risk factors, thus allowing intervention measures to be planned and implemented.

Materials and methods

Study design and sampling technique

This cross-sectional study was carried out in Riyadh over 1-month period and used random cluster sampling. A total of 150 hospitals and private polyclinics were randomly selected from the 15 administrative municipalities of Riyadh. Five government-run hospitals and five private polyclinics were chosen from each area using random numbers generated by Stata V.14. Five dental departments were randomly selected from each hospital or polyclinic and all dentists available were asked to take the survey.

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of MSK pain among dentists. Assuming a 95% confidence level, with an expected prevalence of 85% based on a previous study,13 and 0.05 absolute precision, the required sample size was 196 dentists. Therefore, 224 questionnaires were distributed among dentists and a 91.1% response rate (101 women and 103 men) was achieved.

Study setting and subjects

The study was conducted in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh is divided into 15 municipalities along with the Diplomatic Quarter. The study included male and female Saudi dentists who had worked as dentists for at least 1 year. Dentists with a history of orthopaedic trauma or congenital deformities (of the neck, back and upper extremities) were excluded.

Questionnaire

An existing English questionnaire was adapted for our study.14 The questionnaire was carefully revised so that it fulfilled the objectives of the study. The questionnaire was divided into five main sections with a total of 98 questions. The first section was designed to collect baseline data from study participants on age, gender, marital status, weight, height, smoking, specialty, years of experience, time in contact with patients per day, other characteristics and performance of exercise (30 questions); the other four sections were designed to pool information about neck (16 questions), upper extremity (45 questions) and lower back pain (7 questions) experienced over the previous year. The duration, frequency and intensity of pain was noted. Other related data such as seeking medical attention, quitting the job and taking sick leave were also collected. A 0–10 numeric rating scale for pain severity was used: mild pain was defined as a score between 0 and 4, moderate pain as a score between 5 and 7, and severe pain as a score between 8 and 10.15

Data management and analyses

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) V.22 was used for data management and analysis. Descriptive analyses were carried out by calculating the frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables, while continuous variables were summarised as the mean±SD. Prevalence was calculated with a 95% CI. Univariate and multivariate analyses of logistic regression were conducted to investigate risk factors related to MSK pain in dentists. The univariate model was employed using one predictor at a time to obtain the OR without adjusting for other predictors. The relationship between MSK pain and its potential predictors was determined using forward stepwise logistic regression analysis with a probability of 0.05 for a variable to enter the model. The 95% CI, OR and adjusted OR (aOR) were reported. All the tests were considered significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Participation in the study was voluntary, and each participant could withdraw from the study at any time. The questionnaire was accompanied by a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study and reassuring respondents of the confidentiality of the survey. Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

One hundred and three (50.5%) of the questionnaire respondents were male with a mean±SD age of 38.0±10.6 years for male and female dentists combined. One hundred and thirty (63.7%) participants were married, and all dentists had an average of 13.1 (±10.2) years of experience working as dentists. The mean BMI of participants was 26.6 (±4.7), and 46 (22.5%) of the sample were smokers. Seventy per cent (142) of the participants reported they did not take exercise or engage in sports or fitness activities. Restorative dentists constituted 30.9% of the study population.

We found that 89.2% (182) of participants were right-handed and all dentists worked for a mean of 7.6 hours daily with their patients. In addition, 154 (75.5%) participants frequently bent and twisted themselves to gain better access to and visibility of the oral cavity. Pain caused a reduction in the various activities of daily living in 163 (79.9%) of the sample. Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the dentists who participated in the study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of respondents

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 38.0±10.6 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 101 (49.5) |

| Male | 103 (50.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 74 (36.3) |

| Married | 130 (63.7) |

| BMI | 26.6±4.7 |

| Do you smoke? | |

| No | 158 (77.5) |

| Yes | 46 (22.5) |

| Do you practice any exercise? | |

| No | 142 (69.6) |

| Yes | 62 (30.4) |

| Are you right or left-handed? | |

| Right-handed | 182 (89.2) |

| Left-handed | 22 (10.8) |

| Specialty | |

| Restorative dentistry | 63 (30.9) |

| Endodontic dentistry | 26 (12.7) |

| Paediatric dentistry | 15 (7.4) |

| Periodontics | 12 (5.9) |

| Prosthodontics | 24 (11.8) |

| Orthodontics | 15 (7.4) |

| Maxillofacial surgery | 22 (10.8) |

| General practitioner | 27 (13.2) |

| Experience, years (mean±SD) | 13.1±10.2 |

| Time in contact with patients/day, hours (mean±SD) | 7.6±1.7 |

| Do you excessively bend and twist yourself for better access to or visibility within the oral cavity? | |

| No | 50 (24.5) |

| Yes | 154 (75.5) |

| Did MSK pain cause a reduction in activity? | |

| No | 41 (20.1) |

| Yes | 163 (79.9) |

BMI, body mass index; MSK, musculoskeletal.

Prevalence of work-related MSK pain over a 12-month period

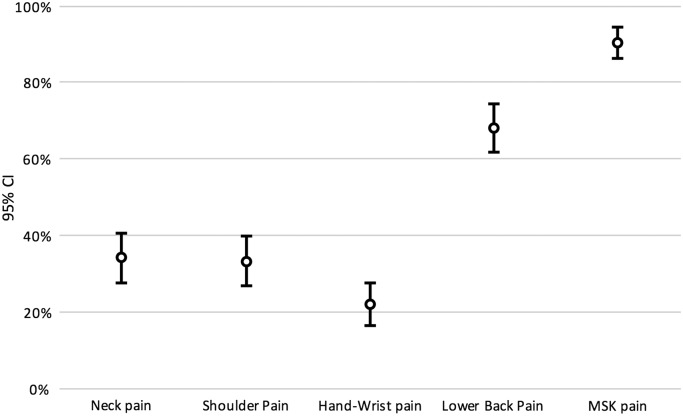

As figure 1 shows, 90.2% (n=184) of the dentists reported MSK pain. Lower back pain had the highest prevalence and was experienced by 68.1% (n=139) of all dentists. The prevalence of neck pain was 34.3% (n=70), while 34.3% (n=68) reported shoulder pain, and 22.1% (n=45) experienced hand and wrist pain.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among dentists.

Characteristics of work related MSK pain over 12-month period

Notably, pain episodes in 86.5% of study participants lasted for less than 4 weeks. The frequency of pain attacks depended on the pain site: the 46.8% of the participants who reported lower back pain experienced the same pain more than five times during the previous year, as did the 11.1% of the sample population who reported either hand or wrist pain. The severity of MSK pain varied among study participants: 28.3% reported the pain was mild, 7.4% that it was moderate and 64.3% that it was severe. Twelve per cent of participants had taken sick leave during the previous 12-month period because of MSK pain, but only 3.8 had sought medical care. Table 2 details the MSK pain characteristics as reported by the study sample.

Table 2.

Characteristics of different types of musculoskeletal (MSK) pain

| Variable | MSK pain (N=184) n (%) |

Neck pain (N=70) n (%) |

Shoulder pain (N=68) n (%) |

Hand-wrist pain (N=45) n (%) |

Back pain (N=139) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | |||||

| <4 weeks | 159 (86.5) | 59 (84.3) | 63 (92.7) | 40 (88.6) | 112 (80.6) |

| 2–3 months | 17 (9.3) | 7 (10.0) | 3 (4.4) | 4 (9.1) | 19 (13.7) |

| 3–6 months | 5 (2.5) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.3) |

| >6 months | 3 (1.6) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (1.4) |

| Frequency of pain attacks (times) | |||||

| <5 | 138 (75) | 58 (82.9) | 51 (75.0) | 40 (88.9) | 74 (53.2) |

| >5 | 46 (25) | 12 (17.1) | 17 (25.0) | 5 (11.1) | 65 (46.8) |

| Intensity of pain (scale of 1–10) | |||||

| Mild (1–3) | 52 (28.3) | 25 (35.7) | 17 (25.0) | 19 (42.2) | 14 (10.1) |

| Moderate (4–7) | 118 (64.3) | 45 (64.3) | 50 (73.5) | 24 (53.3) | 92 (66.2) |

| Severe (8–10) | 14 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (4.4) | 33 (23.8) |

| Sought medical attention | 7 (3.8) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (4.4) | 7 (5) |

| Changed job | 3 (1.6) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) |

| Took sick leave in past 12 months | 22 (12) | 5 (7.3) | 11 (16) | 3 (6.7) | 25 (18) |

| Number of times taken sick leave | |||||

| 0 times | 167 (90.9) | 65 (92.8) | 65 (95.6) | 42 (93.3) | 144 (82) |

| 1–5 times | 15 (8) | 5 (7.3) | 3 (4.4) | 3 (6.7) | 19 (13.7) |

| >5 times | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.3) |

Univariate logistic regression analysis of the predictors of MSK pain

Age was associated with shoulder pain and lower back pain in the univariate analyses. There was no association between gender, BMI or smoking habit and MSK pain. However, marital status was significantly associated with lower back pain, with married participants experiencing more lower back pain than single participants (OR 0.33; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.62).

In addition, lower back pain was related to the time the dentist spent with patients (OR 0.28; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.54), while shoulder pain (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06) and lower back pain (OR 1.06; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.10) were significantly related to years of experience.

Periodontists, orthodontists, restorative dentists, prosthodontists and paediatric dentists experienced more MSK pain than general dentists or maxillofacial surgeons. Shoulder and lower back pain was more common among dentists who did not take any exercise and among dentists who did a lot of bending and twisting. Table 3 details the univariate analyses of MSK pain over the previous 12 months.

Table 3.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of the predictors of musculoskeletal (MSK) pain

| Variable(s) | MSK pain OR (95% CI) |

Neck pain OR (95% CI) |

Shoulder pain OR (95% CI) |

Hand-wrist pain OR (95% CI) |

Lower back pain OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.19) | 1.026 (0.99 to 1.05) | 1.033 (1.01 to 1.062) | 1.006 (0.98 to 1.04) | 1.068 (1.03 to 1.11) |

| p Value | 0.005 | 0.065 | 0.020 | 0.692 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 0.78 (0.31 to 1.98) | 0.67 (0.37 to 1.19) | 1.47 (0.82 to 2.64) | 1.09 (0.56 to 2.11) | 1.60 (0.88 to 2.91) |

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p Value | 0.606 | 0.171 | 0.199 | 0.808 | 0.121 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.36) | 0.80 (0.43 to 1.46) | 0.94 (0.51 to 1.72) | 0.85 (0.42 to 1.70) | 0.33 (0.18 to 0.62) |

| Married | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p Value | <0.001 | 0.463 | 0.837 | 0.642 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.11) | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) |

| p Value | 0.724 | 0.392 | 0.160 | 0.612 | 0.938 |

| Specialty | |||||

| Restorative dentistry | 3.76 (1.23 to 11.55) | 1.16 (0.51 to 2.63) | 0.54 (0.24 to 1.22) | 1.27 (0.50 to 3.24) | 2.82 (1.28 to 6.21) |

| Periodontics/prosthodontics | 11.35 (1.40 to 91.93) | 1.79 (0.72 to 4.42) | 1.10 (0.45 to 2.66) | 0.72 (0.22 to 2.36) | 2.37 (0.96 to 5.84) |

| Paediatrics/orthodontics | 9.41 (1.16 to 76.58) | 1.07 (0.40 to 2.90) | 0.63 (0.23 to 1.70) | 2.57 (0.91 to 7.25) | 5.21 (1.71 to 15.83) |

| Endodontics | 8.11 (0.99 to 66.36) | 2.14 (0.80 to 5.76) | 1.72 (0.66 to 4.51) | 1.33 (0.42 to 4.27) | 2.83 (1.01 to 7.93) |

| GP/maxillofacial dentristry | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p Value | 0.010 | 0.466 | 0.137 | 0.259 | 0.019 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Non-smoker | 1.16 (0.40 to 3.39) | 0.86 (0.44 to 1.70) | 1.19 (0.58 to 2.41) | 1.45 (0.62 to 3.39) | 1.71 (0.87 to 3.38) |

| Smoker | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p Value | 0.783 | 0.668 | 0.636 | 0.388 | 0.121 |

| Time spent per patient | 1.12 (0.87 to 1.43) | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.28) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.23) | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.13) | 1.20 (1.00 to 1.44) |

| p Value | 0.381 | 0.483 | 0.787 | 0.466 | 0.039 |

| Experience | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.19) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.10) |

| p Value | 0.007 | 0.069 | 0.029 | 0.787 | 0.001 |

| Do you excessively bend and twist yourself for better access to or visibility within the oral cavity? | |||||

| No | 0.14 (0.05 to 0.36) | 0.52 (0.25 to 1.08) | 0.35 (0.16 to 0.78) | 1.00 (0.46 to 2.15) | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.54) |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p Value | <0.001 | 0.080 | 0.010 | 0.991 | <0.001 |

| Do you exercise? | |||||

| No | 2.538 (0.998 to 6.456) | 1.412 (0.740 to 2.695) | 2.383 (1.185 to 4.791) | 2.000 (0.897 to 4.457) | 2.337 (1.251 to 4.366) |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p Value | 0.050 | 0.295 | 0.015 | 0.090 | 0.008 |

BMI, body mass index.

Forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis of MSK pain predictors

Gender, age and marital status were found to be predictors for at least one type of MSK pain. Older age was associated with lower back pain (aOR 1.07; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.11), women had double the risk of lower back pain compared with men (aOR 2.17; 95% CI 1.12 to 4.20), and participants who did not exercise had more shoulder pain than those who did exercise (aOR 2.31; 95% CI 1.14 to 4.69).

Marital status was associated with MSK pain (aOR 0.12; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.42) as was orthodontic and paediatric dentistry (aOR 11.84; 95% CI 1.28 to 109.49). More importantly, excessive bending and twisting for better access to the oral cavity was significantly associated with MSK pain, shoulder pain and lower back pain. Table 4 summarises the results of forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis of MSK pain over the previous 12 months.

Table 4.

Forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis of musculoskeletal (MSK) pain predictors

| Region | Variable | Category | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSK pain | Marital status | Single | 0.12 (0.04 to 0.42) | 0.001 |

| Married | 1 | |||

| Specialty | Restorative dentistry | 2.40 (0.68 to 8.51) | 0.174 | |

| Periodontics/prosthodontics | 6.23 (0.67 to 58.04) | 0.108 | ||

| Paediatrics/orthodontics | 11.84 (1.28 to 109.49) | 0.029 | ||

| Endodontics | 5.97 (0.63 to 56.11) | 0.118 | ||

| GP/maxillofacial dentistry | 1 | |||

| Bending and twisting for better access | No | 0.16 (0.05 to 0.47) | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 1 | |||

| Shoulder pain | Bending and twisting for better access | No | 0.37 (0.16 to 0.81) | 0.013 |

| Yes | 1 | |||

| Exercising | No | 2.31 (1.14 to 4.69) | 0.021 | |

| Yes | 1 | |||

| Lower back pain | Age | Continuous | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) | <0.001 |

| Gender | Female | 2.17 (1.12 to 4.20) | 0.021 | |

| Male | 1 | |||

| Bending and twisting for better access | No | 0.30 (0.15 to 0.61) | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 1 |

Discussion

MSK pain is common among dentists with various factors increasing its prevalence. As previous studies have shown that dentists experience common MSK symptoms,1 3 7 8 11 13 16 it is important to investigate the causes contributing to this work-related pain among Saudi dentists. When these factors have been identified then ergonomic solutions can be implemented.

The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of MSK pain and identify potential risk factors among dentists in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study reveals a high prevalence of MSK pain during the previous 12 months among Saudi dentists in Riyadh (92.5%) with age, gender, specialty and poor workplace ergonomics being predictors of MSK pain. The 92.5% prevalence of MSK pain is higher than that reported in other countries such as India, Iran, China and Australia17–20 and is much higher than that found by Alghadir et al.13 The present study also showed that the prevalence of neck pain was around 34.3% which is much lower than that among Dutch and Australian dentists who reported neck pain prevalences of 51% and 57.5%, respectively.21 22 However, the 27.6% prevalence of neck pain in our study was higher than the prevalence of 19.8% reported in Saudi Arabian dental hygienists.12 MSK pain among Saudi dentists in Riyadh (92.5%) is much higher than among the general population in Saudi Arabia.23 MSK pain was reported by 1477 (25.4%) respondents in the community, of whom 762 (13.1%) were men and 715 (12.3%) were women. Also, 31.2% of 1000 adults above 18 years of age surveyed in a recent study complained of MSK pain during the period of the study.24 MSK pain among construction workers in Saudi Arabia was also found to be lower than in our sample with 80 (48.5%) of 165 workers reporting MSK pain.25

The 34.3% prevalence of shoulder pain among our participants was lower than the 60% reported in US dental hygienists.26 Furthermore, a much higher prevalence of 81% was found among Swedish dental hygienists.27 Another study carried out among dental personnel in Saudi Arabia revealed that 61% of respondents experienced shoulder pain. However, that study included dental hygienists, dental assistants and dental technicians, in addition to dentists, thus limiting the comparability of the findings to our results.13

In addition, 44% of Polish dentists reported hand and wrist pain,3 which is much higher than the 22.1% who experienced such pain in our study. However, our findings were similar to those of a Dutch study where 14% and 21% of dentists experienced wrist and hand pain, respectively.21 A literature review of the general health of dentists stated that dental hygienists experience a higher prevalence of hand and wrist pain.28

Previous reviews showed that lower back pain was the most common MSK problem amongst dentists.2 28 This agrees with our study where 68.1% of dentists experienced lower back pain and a Polish study which demonstrated a prevalence of 60.1%.3 Similarly, 60% of Danish dentists29 and 53.7% of dentists in Queensland, Australia reported lower back pain,22 while a previous study from Saudi Arabia showed that 60% of dentists had lower back pain.13 This lower figure from Saudi Arabia could be explained by the inclusion of only 225 members of one dental association in addition to dentists from other countries.

Age, gender, marital status, specialty and awkward posture and movements, like twisting and bendng, contribute to the high prevalence of MSK pain among Saudi dentists. Studies have shown that MSK symptoms increase with age as older dentists have spent more time with patients and eventually experience complicated pain.30

There were inconsistent findings concerning the effect of the number of years worked on the incidence and prevalence of MSK disorders. Some studies reported that MSK disorders increase by years of work.31 MSK symptoms were significantly associated with work experience at the univariate level, but other studies showed that MSK pain in dentists was negatively correlated with years worked.22 29 Some researchers and scholars believed that dentists with a lot of experience learn to adapt their work posture and avoid MSK disorders, or that dentists with MSK problems might leave dentistry as a profession.9

The study also showed that female dentists were approximately 1.5 times more likely to experience shoulder pain than male dentists. Similarly, a study of Thai dentists found that female dentists experienced worse shoulder pain than their male counterparts.32 Another study among dentists from New South Wales, Australia, revealed that female dentists were more likely to rate their pain as very severe but that gender was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis of overall MSK pain.33 A study conducted by Muralidharan et al34 revealed almost the same findings.

Marital status was found to be associated with lower back pain. Married participants had more lower back pain than single participants, which finding was consistent with other studies that investigated lower back pain in the general population.35–37 Marriage can also affect physiological mechanisms after it is consummated.36

Awkward postures while sitting and bending and twisting are highly associated with shoulder and lower back pain. A study conducted on the working postures of dentists and dental hygienists found that 86% of the time they worked with their neck bent (flexed) by at least 30°, and at least 50% of their time with their trunk flexed by at least 30°.38 Studies have shown that excessive flexion can cause stress to the spine and limbs.39 When dentists are operating, they often have to hold their wrists in an awkward position to access the mouth and provide optimal treatment. In addition, using small dental instruments is stressful as it requires nimble fingers and uncomfortable shoulder positions, which eventually create overload and pressure on the shoulder. Future studies are recommended to investigate possible correlation between different tool sizes and MSK symptoms so that workplace ergonomics in dentistry can be improved.

As the present study shows, the time the dentist spent with each patient was highly correlated with the presence of lower back pain. Participants working for more than 2 hours without a break are more likely to have neck and lower back pain. A previously study reports that over 90% of dentist's time was taken up with appointments which lasted 10–60 min.20 A study on Danish dentists showed that the length of appointments seemed to influence neck pain,29 while another study showed that patient treatment time was positively associated with MSK pain.40

Moreover, paediatric dentists, periodontists, prosthodontists, orthodontists, restorative dentists and endodontic dentists were reported to be more likely to have MSK pain compared to general practitioners or maxillofacial surgeons. Rafie et al19 stated that oral surgeons and prosthodontists were the groups most likely to have MSK disorders. Ratzon et al31 also showed that the high prevalence of MSK disorders in oral surgeons was caused by very stressful work. In addition, Varmazyar et al41 showed that prosthodontists were more likely to have MSK pain because they were required to move more during their work and oral surgeons because their work required great concentration, endurance and stamina.

The current study also shows a significant association between regular exercise and less MSK pain. Dentists who took even a small amount of exercise were less likely to experience lower back pain than dentists who took no exercise. Indeed, regular aerobic and stretching exercises are key for preventing damage and strengthening the MSK system in dental workers.42 43 However, the present study showed that more than 69% of dentists did not take regular exercise in contrast to a study carried out in China where only 30% of dentists reported no exercise.20

The working environment and normal daily activities of dentists are negatively affected by the high prevalence of MSK pain. The present study revealed that MSK pain caused a reduction in activity in 79.9% of respondents. In addition, 12% of participants took sick leave during the previous 12 months because of work-related pain, 3.8% sought medical care for pain, and in 1.6% MSK pain was severe enough to cause them to change their profession. A study carried out in Baghdad showed that 24% of dentists resigned because of MSK pain, and in another study from Queensland, Australia, one in 10 dentists had taken sick leave during the previous 12 months.1 22 One study showed that 46.6% of dentists in Surat, India sought medical care for MSK symptoms, which is alarming.10 MSK disorders cost billions of dollars every year. For instance, in Canada, MSK disorders cost $C25.6 billion in 1994, with $C8.1 billion spent on back and spine disorders.44 Another study showed that MSK pain causes many dentists to decrease their working hours or leave the profession altogether. These negative effects have significant consequences for society and the economy.44 45

Prospective studies should be carried out on the longitudinal effects of physical and psychosocial risk factors on the development of MSK symptoms in dental practitioners. Self-reported surveys may introduce bias but are inexpensive and convenient for collecting primary data. Physical examinations and assessments are more reliable but are expensive and time-consuming. Interpretation of published data should be done cautiously as definitions of MSK disorders, sample populations, response rates, prevalences and other contributory factors may vary.

It is important to control pain as it has a negative effect on dentists' performance. Therefore, measures to manage pain should be carefully designed and thoroughly evaluated. Non-compliance, insufficient education about pain control and ineffective policies to improve the working environment are major challenges to providing better pain management and minimising occupational MSK.46–48

Recommendations

The present study reveals that there is a high prevalence of MSK pain among Saudi dentists in Riyadh. Therefore, it is recommended that the ergonomics of dental surgeries be improved. Training courses covering occupational health, ergonomics, workplace organisation and psychosocial coping skills should be offered to dentists. Further studies on the ergonomics of dental surgeries are encouraged.

Acknowledgments

Authors would thank Mrs. Ghada Al-yahya for her help with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: HSA and OAA-M designed the study and revised the manuscript. NSA and WMA collected data and wrote the manuscript. EMM analysed and interpreted data. OAA-M contributed to the interpretation of data.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mohammad ZJ. Musculoskeletal disorders: back and neck problems among a sample of Iraqi dentists in Baghdad city. J Baghdad Coll Dent 2011;23:90–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes M, Cockrell D, Smith DR. A systematic review of musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals. Int J Dent Hyg 2009;7:159–65. 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szymanska J. Disorders of the musculoskeletal system among dentists from the aspect of ergonomics and prophylaxis. Ann Agric Environ Med 2002;9:169–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maguire M, O'Connell T. Ill-health retirement of schoolteachers in the Republic of Ireland. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2007;57:191–3. 10.1093/occmed/kqm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNee C, Kieser JK, Antoun JS et al. Neck and shoulder muscle activity of orthodontists in natural environments. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013;23:600–7. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayatollahi J, Ayatollahi F, Ardekani AM et al. Occupational hazards to dental staff. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:2–7. 10.4103/1735-3327.92919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayers KMS, Thomson WM, Newton JT et al. Self-reported occupational health of general dental practitioners. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:142–8. 10.1093/occmed/kqp004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kierklo A, Kobus A, Jaworska M et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dentists—a questionnaire survey. Ann Agric Env Med 2011;18:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Occupational health problems in modern dentistry: a review. Ind Health 2007;45:611–21. 10.2486/indhealth.45.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah S, Dave B. Prevalence of low back pain and its associated risk factors among doctors in Surat. Int J Heal Sci Res 2012;2:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samotoi A, Moffat SM, Thomson WM. Musculoskeletal symptoms in New Zealand dental therapists: prevalence and associated disability. N Z Dent J 2008;104:49–53; quiz 65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Wazzan KA, Almas K, Al Shethri SE et al. Back & neck problems among dentists and dental auxiliaries. J Contemp Dent Pr 2001;2:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alghadir A, Zafar H, Iqbal ZA. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals in Saudi Arabia. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:1107–12. 10.1589/jpts.27.1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon 1987;18:233–7. 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschfeld G, Zernikow B. Variability of ‘optimal’ cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain: neglected problems when comparing groups. Pain 2013;154:154–9. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pargali N, Jowkar N. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among dentists in Shiraz, Southern Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med 2010;1:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakzewski L, Naser-Ud-Din S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Australian dentists and orthodontists: risk assessment and prevention. Work 2015;52:559–79. 10.3233/WOR-152122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar VK, Kumar SP, Baliga MR. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal complaints among dentists in India: a national cross-sectional survey. Indian J Dent Res 2013;24:428–38. 10.4103/0970-9290.118387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rafie F, Zamani Jam A, Shahravan A et al. Prevalence of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders in dentists: symptoms and risk factors. J Environ Public Health 2015;2015:517346 10.1155/2015/517346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng B, Liang Q, Wang Y et al. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms of the neck and upper extremity among dentists in China. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006451 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Droeze EH, Jonsson H. Evaluation of ergonomic interventions to reduce musculoskeletal disorders of dentists in the Netherlands. Work 2005;25:211–20. http://iospress.metapress.com/content/03KVRJ0CP6C0WL12\nhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16179770 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leggat PA, Smith DR. Musculoskeletal disorders self-reported by dentists in Queensland, Australia. Aust Dent J 2006;51:324–7. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Arfaj AS, Alballa SR, Al-Dalaan AN et al. Musculoskeletal pain in the community. Saudi Med J 2003;24:863–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moussa S, Al Zaylai F, Alomar A et al. Musculoskeletal pain in Hail community: medical and epidemiology study; Saudi Arabia. Int J Sci Res 2015;4:1292–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alghadir A, Anwer S. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in construction workers in Saudi Arabia. Sci World J 2015;2015:1–5. 10.1155/2015/529873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anton D, Rosecrance J, Merlino L et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms and carpal tunnel syndrome among dental hygienists. Am J Ind Med 2002;42:248–57. 10.1002/ajim.10110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Öberg T, Öberg U. Musculoskeletal complaints in dental hygiene: a survey study from a Swedish county. J Dent Hyg 1993;67:257–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puriene A, Janulyte V, Musteikyte M et al. General health of dentists. Literature review. Stomatologija 2007;9:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finsen L, Christensen H, Bakke M. Musculoskeletal disorders among dentists and variation in dental work. Appl Ergon 1998;29:119–25. 10.1016/S0003-6870(97)00017-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares JJF, Sundin O, Grossi G. Age and musculoskeletal pain. Int J Behav Med 2003;10:181–90. 10.1207/S15327558IJBM1002_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ratzon NZ, Yaros T, Mizlik A et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms among dentists in relation to work posture. Work 2000;15:153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chowanadisai S, Kukiattrakoon B, Yapong B et al. Occupational health problems of dentists in southern Thailand. Int Dent J 2000;50:36–40. 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2000.tb00544.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall ED, Duncombe LM, Robinson RQ et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms in New South Wales dentists. Aust Dent J 1997;42:240–6. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb00128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muralidharan D, Fareed N, Shanthi M. Musculoskeletal disorders among dental practitioners: does it affect practice? Epidemiol Res Int 2013;2013:1–6. 10.1155/2013/716897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knox J, Orchowski J, Scher DL et al. The incidence of low back pain in active duty United States military service members. Spine 2011;36:1492–500. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f40ddd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biglarian A, Seifi B, Bakhshi E et al. Low back pain prevalence and associated factors in Iranian population: findings from The National Health Survey. Pain Res Treat 2012;2012:21–4. 10.1155/2012/653060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altinel L, Kose KC, Ergan V et al. [The prevalence of low back pain and risk factors among adult population in Afyon region, Turkey]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2008;42:328–33. 10.3944/AOTT.2008.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marklin RW, Cherney K. Working postures of dentists and dental hygienists. J Calif Dent Assoc 2005;33:133–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szymanska J. Occupational hazards of dentistry. Ann Agric Environ Med 1999;6:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ylipaa V, Arnetz BB, Benko SS et al. Physical and psychosocial work environments among Swedish dental hygienists: Risk indicators for musculoskeletal complaints. Swed Dent J 1997;21:111–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varmazyar S, Amini M, Kiafar S. Ergonomic evaluation of work conditions in Qazvin dentists and its association with musculoskeletal disorders using REBA method. J Islam Dent Assoc IRAN 2012;24:182–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;134:1604–12. 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrews N, Vigoren G. Ergonomics: muscle fatigue, posture, magnification, and illumination. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2002;23:261–6, 268, 270 passim; quiz 274. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12785139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coyte PC, Asche CV, Croxford R et al. The economic cost of musculoskeletal disorders in Canada. Arthritis Care Res 1998;11:315–25. 10.1002/art.1790110503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morse T, Bruneau H, Dussetschleger J. Musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and shoulder in the dental professions. Work 2010;35:419–29. 10.3233/WOR-2010-0979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souza CA, Oliveira LM, Scheffel C et al. Quality of life associated to chronic pelvic pain is independent of endometriosis diagnosis--a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:41 10.1186/1477-7525-9-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hooten WM, Timming R, Belgrade M, et al. For the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Health care guideline: assessment and management of chronic pain. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement website November 2013: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/bw798b/chronicpain.pdf.

- 48.Bond M. Pain education issues in developing countries and responses to them by the International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain Res Manag 2011;16:404–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]