Abstract

Bosutinib, a dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor, has shown potent activity against chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). In this phase 1/2 study we evaluated bosutinib in patients with chronic phase imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant CML. Part 1 was a dose-escalation study to determine the recommended starting dose for part 2; part 2 evaluated the efficacy and safety of bosutinib 500 mg once-daily dosing. The study enrolled 288 patients with imatinib-resistant (n = 200) or imatinibintolerant (n = 88) CML and no other previous kinase inhibitor exposure. At 24 weeks, 31% of patients achieved major cytogenetic response (primary end point). After a median follow-up of 24.2 months, 86% of patients achieved complete hematologic remission, 53% had a major cytogenetic response (41% had a complete cytogenetic response), and 64% of those achieving complete cytogenetic response had a major molecular response. At 2 years, progression-free survival was 79%; overall survival at 2 years was 92%. Responses were seen across Bcr-Abl mutants, except T315I. Bosutinib exhibited an acceptable safety profile; the most common treatment-emergent adverse event was mild/moderate, typically self-limiting diarrhea. Grade 3/4 nonhematologic adverse events (> 2% of patients) included diarrhea (9%), rash (9%), and vomiting (3%). These data suggest bosutinib is effective and tolerable in patients with chronic phase imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant CML. This trial was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00261846.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) accounts for ∼ 15% of adult leukemias,1 with an estimated 4870 new cases in the United States in 2010 and 440 disease-associated deaths.2 Available tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as imatinib, are effective in many patients3–5 but have toxicities that potentially are associated with off-target effects.3,6–10 In the International Randomized Study of IFN and STI571 (IRIS) of patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase (CP) CML, treatment with imatinib was associated with an estimated major cytogenetic response (MCyR) rate of 87% at 18 months11 and an event-free survival rate at 60 months of 83%.12 However, imatinib commonly was associated with certain toxicities (eg, edema, musculoskeletal events, gastrointestinal events, rash, fatigue, headache, and grade 3/4 myelosuppression) in this study.11,12 Imatinib-resistant disease has also been encountered.12–14 Second-generation TKIs (eg, nilotinib, dasatinib) are effective in approximately one-half of patients who exhibit resistance to imatinib, and each has a unique toxicity profile.4,6,7,10,15,16 Alternative treatments are needed for patients with CML who are resistant or intolerant to imatinib or second-generation TKIs.

Bosutinib (SKI-606) is a small molecule, orally bioavailable, dual Src/Abl TKI with potent preclinical Bcr-Abl inhibitory activity in imatinib-resistant CML cell lines, with one-half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values approximately 15- to 100-fold lower than those obtained with imatinib.17,18 Unlike other second-generation TKIs, bosutinib exhibits minimal inhibitory activity against c-KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor,17,19 2 nonspecific targets potentially associated with toxicities observed with other TKIs.17,19–21 Bosutinib demonstrated preclinical activity against most imatinib-resistant mutants of Bcr-Abl, with the exception of T315I and V299L.17,22 In this phase 1/2 study, we assessed the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of bosutinib in patients with imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant CP CML.

Patients and methods

Patient population

Eligible patients were at least 18 years of age with Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) CML or Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia exhibiting imatinib resistance (primary or secondary resistance) or intolerance. In the current report we describe only those patients with CP CML receiving bosutinib treatment in the second-line setting; data for the other cohorts (ie, advanced leukemias or CP with > 1 prior TKI) will be reported separately. For patients with CP CML, primary imatinib resistance was defined as failure to achieve or maintain any of the following measurements: hematologic improvement within 4 weeks, a complete hematologic response (CHR) after 12 weeks, any cytogenetic response by 24 weeks, or a MCyR by 12 months with an imatinib treatment dose of 600 mg or greater.23 Acquired resistance was defined as loss of a MCyR or any hematologic response. Imatinib intolerance was defined as an inability to take imatinib because of imatinib-related grade 4 hematologic toxicity lasting longer than 7 days; imatinib-related grade 3 or greater nonhematologic toxicity; persistent grade 2 toxicity not responding to dose reductions and medical management; or loss of previously attained response on lower-dose imatinib among patients with previous toxicity. The definition of CP CML was as reported previously.3,4,6

Patients were required to have previous imatinib therapy; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 1; no antiproliferative or antileukemia treatment within 7 days of bosutinib initiation (except hydroxyurea or anagrelide); corrected QT (QTc) interval < 470 ms at screening; and, for CP imatinib-resistant patients, absolute neutrophil count > 1000 × 109/L. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each site. This trial is registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00261846.

Study design

This was a phase 1/2, open-label, 2-part study. Part 1 was a dose-escalation study of standard 3 + 3 design with successive cohorts of 3-6 patients with CP imatinib-resistant CML. Each cohort was evaluated for safety over the course of 28 days before enrollment of the next cohort to establish the maximum tolerated dose (MTD; greatest dose at which no more than one patient experienced a dose-limiting toxicity [DLT] possibly related to bosutinib). A DLT included either of the following events that occurred during the first 28 days of bosutinib therapy and was considered at least possibly related to bosutinib: any grade 3/4 clinically relevant nonhematologic toxicity occurring despite supportive care or any clinically significant grade 2 or greater nonhematologic toxicity requiring ≥ 14 days to resolve.

In part 2 we evaluated the efficacy and safety of bosutinib. The primary end point was the MCyR rate at 24 weeks in patients with CP imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant CML and no previous TKI exposure other than imatinib. Prespecified interim analyses conducted at 25%, 50%, and 75% of data availability evaluated the proportion of imatinib-resistant patients who achieved a MCyR at week 24. All patients treated with bosutinib who were followed for 24 weeks of treatment or permanently discontinued (or died) with an adequate baseline cytogenetic assessment were included in the interim analyses.

Oral bosutinib was administered daily, except the day 2 dose was skipped in part 1 to provide a 48-hour pharmacokinetic profile. Treatment continued until disease progression (transformation to accelerated or blast phase, or loss of previously attained response), unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. During part 1, successive cohorts received escalating doses of bosutinib, starting at 400 mg. During part 2, patients received bosutinib 500 mg/d (dose determined in part 1); intrapatient dose escalation to bosutinib 600 mg/d was allowed for lack of efficacy (failure to achieve CHR by week 8 or complete cytogenetic response [CCyR] by week 12) if grade 3 or greater bosutinib-related toxicity had not been observed. Doses were held or reduced in 100-mg decrements on the basis of severity and duration of treatment-related toxicities. Patients were removed from the study if they were unable to tolerate a bosutinib dose of ≥ 300 mg/d.

Safety and efficacy assessments

Screening was conducted within 14 days of patient registration and included medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, complete blood count, serum chemistry, urinalysis, and RT-PCR for Bcr-Abl; BM aspiration was performed within 28 days of registration. During the first 2 years, BM examination and cytogenetics were performed every 3 months. Complete blood count with differential was performed at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 12, and every 3 months thereafter; after 2 years, assessments were performed every 6 months.

Molecular response was assessed with non-nested RT-PCR for the Bcr-Abl transcript (Bcr-Abl/Abl ratio) performed at a central laboratory (Quest Diagnostics) monthly for the first 3 months, every 3 months through 2 years, and every 6 months thereafter. Because of logistical constraints, molecular response was not evaluated for patients enrolled in China, India, Russia, and South Africa. Sequencing of exons 4-9 of the Abl kinase domain (ATP binding domain and activation loop) was performed to identify mutations before the first dose and at treatment completion. The sensitivity of detecting mutant alleles was 20% in the background of wild-type cells. An electrocardiogram was obtained immediately before and 2, 4, and 6 hours after bosutinib dosing on day 1, immediately before and 2, 4, 6, and 20-23 hours after bosutinib dosing on day 21, and at the end of treatment. Adverse events (AEs) were graded by the use of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3.0.

The criteria for cytogenetic responses were standard23: CCyR, 0% Ph+ metaphases; partial cytogenetic response, 1%-35%; MCyR, 0%-35%; minor cytogenetic response, 36%-65%; minimal cytogenetic response, 66%-95%; no cytogenetic response, > 95%. At least 20 metaphases were required for postbaseline assessment. If fewer than 20 metaphases were available, FISH analysis of BM aspirate for the presence of Bcr-Abl could be used if ≥ 200 cells were analyzed; cytogenetic responses were determined as indicated previously except that < 1% of positive cells was considered as CCyR by FISH analysis.

To be a responder for cytogenetic response, the patient must have had an improvement in cytogenetic response from baseline. Molecular responses were categorized as complete (CMR; undetectable Bcr-Abl, with a RT-PCR sensitivity of ≥ 5 log) or major (MMR; ≥ 3 log reduction from standardized baseline). Hematologic responses were required to be confirmed and of ≥ 4 weeks in duration, with peripheral blood and/or BM documentation (supplemental Table 2). To be considered a responder for hematologic response, the patient must have had an improvement from baseline or maintained his or her baseline CHR. Disease progression was defined as evolution from CP to accelerated or blast phase; doubling of white blood cell count over at least 1 month with a confirmed second count > 20 × 109/L; or loss of confirmed CHR or loss of MCyR with an increase of ≥ 30% in Ph+ metaphases.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic analyses performed on data from part 1 with the use of noncompartmental methods are reported. Samples were collected before bosutinib administration and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 hours after administration on day 1 and before and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 24 hours after administration on day 15.

Statistical analyses

After the 28-day safety evaluation, patients recruited in part 1 were further analyzed along with patients from part 2 for both efficacy and long-term safety. Rate of MCyR at 24 weeks was evaluated for all treated patients by the use of response rates and confidence intervals (CIs). Secondary end points were summarized with the use of descriptive statistics, such as the Kaplan-Meier method, and response rates. Overall survival was calculated from the start date of therapy to the date of death, with patients censored at the last contact (patients were followed for 2 years after stopping treatment). Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the start date of therapy to the date of progression (until study completion) or death. Time to response was calculated from the start date of therapy to the first date of response (confirmed response for hematologic response and unconfirmed response for cytogenetic and molecular responses). Duration of response was calculated from the first date of response to confirmed loss, progressive disease, or death. For time-to-event end points except overall survival, patients were censored at the last follow-up visit for those not known to have the respective end point. Evaluable patients for response for a given end point (secondary efficacy analyses) included those patients who had an adequate baseline assessment for that particular end point. All patients who received at least one dose of bosutinib were included in the safety analysis. AEs were described both with and without regard to causality. Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed with the use of noncompartmental methods and other analyses, as appropriate.

Results

Patients

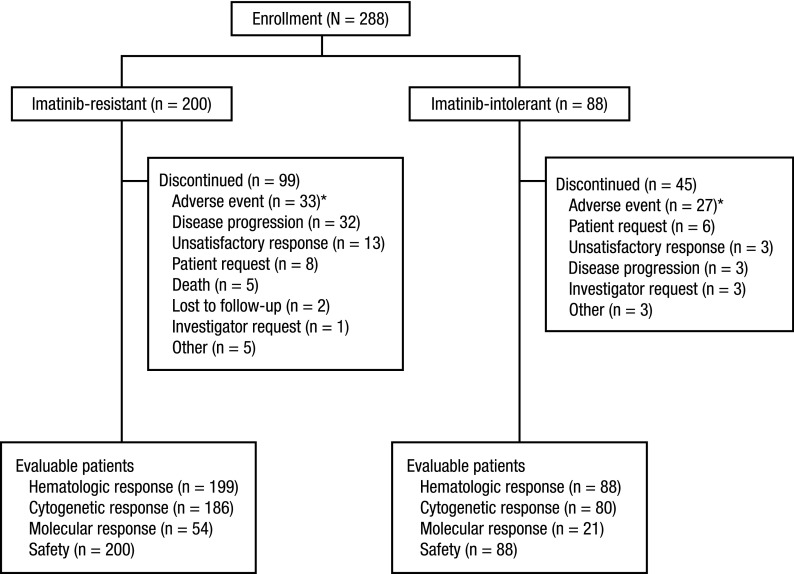

A total of 288 patients with imatinib-resistant (n = 200; 69%) or imatinib-intolerant (n = 88; 31%) CP CML were enrolled between January 24, 2006, and July 14, 2008, in 58 centers in 27 countries (Figure 1). Among these 288 patients, 17 were CP patients included in part 1. As of the data cutoff for this analysis on June 3, 2010, the median duration of follow-up was 24.2 months. Demographic and baseline disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Bcr-Abl mutation status at baseline was available for 115 (40%) patients (83/200 [42%] imatinib-resistant and 32/88 [36%] imatinib-intolerant patients); 65 (57%) of patients who underwent successful Abl kinase domain sequencing had at least 1 mutation identified.

Figure 1.

Disposition of patients. A total of 288 patients were enrolled in part 2, including 200 imatinib-resistant patients and 88 imatinib-intolerant patients. *AEs leading to withdrawal in 2 or more imatinib-resistant patients included thrombocytopenia (n = 6), aspartate aminotransferase elevation (n = 4), alanine aminotransferase elevation (n = 3), diarrhea (n = 3), neutropenia (n = 2), anemia (n = 2), leukopenia (n = 2), and vomiting (n = 2). AEs leading to withdrawal in 2 or more imatinib-intolerant patients included thrombocytopenia (n = 8), diarrhea (n = 3), alanine aminotransferase elevation (n = 3), aspartate aminotransferase elevation (n = 2), dyspnea (n = 2), neutropenia (n = 2), pancytopenia (n = 2), and rash (n = 2).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographic and disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Imatinib resistant (n = 200) |

Imatinib intolerant (n = 88) |

Total (N = 288) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| Median | 51.0 | 54.5 | 53.0 | |||

| Range | 18-86 | 23-91 | 18-91 | |||

| Sex, male | 116 | 58 | 38 | 43 | 154 | 53 |

| Hematologic analysis, 109/L | ||||||

| White blood cell count | ||||||

| Median | 6.7 | 5.9 | 6.5 | |||

| Range | 2.1-151 | 2.1-160.7 | 2.1-151 | |||

| Platelet count | ||||||

| Median | 261.5 | 202.5 | 237.5 | |||

| Range | 47-2436 | 48-2251 | 47-2436 | |||

| Duration of disease, y | ||||||

| Median | 4.0 | 2.8 | 3.6 | |||

| Range | 0.1-15.1 | 0.1-13.6 | 0.1-15.1 | |||

| Treatment history | ||||||

| No. of previous therapies* | ||||||

| 1 | 131 | 66 | 65 | 74 | 196 | 68 |

| 2 | 69 | 35 | 23 | 26 | 92 | 32 |

| Previous IFN | 69 | 35 | 23 | 26 | 92 | 32 |

| Previous stem cell transplantation | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| Features of imatinib treatment | ||||||

| Duration of previous imatinib treatment, y | ||||||

| Median | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.2 | |||

| Range | 0.4-8.8 | < 0.1-8.3 | < 0.1-8.8 | |||

| Previous complete hematologic response with imatinib | 164 | 82 | 55 | 63 | 219 | 76 |

| Reason for stopping imatinib | ||||||

| Adverse event (intolerance)† | 1 | 1 | 86 | 98 | 87 | 33 |

| Disease progression | 163 | 92 | 1 | 1 | 164 | 62 |

| Regimen completed | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| Other | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 |

| Missing‡ | 22 | 0 | 22 | |||

| 1 or more Bcr-Abl mutations detected§ | 57/83 | 69 | 8/32 | 25 | 65/115 | 57 |

Includes previous tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies. Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding.

Patients simultaneously meeting the protocol definitions for imatinib resistance and imatinib intolerance are categorized as having imatinib resistance.

The reason for stopping imatinib was not reported.

Total of 83 imatinib-resistant and 32 imatinib-intolerant patients assessed for mutation status at baseline.

Dose escalation cohort

Eighteen patients were enrolled in part 1, 17 with imatinib-resistant CP CML and one with accelerated-phase CML (25% and 30% basophils in peripheral blood and BM, respectively, at enrollment); this patient with accelerated-phase CML was included in the pharmacokinetic and safety evaluations in part 1 but not in efficacy analyses for the second-line CP CML population. Three patients each were enrolled in the 400- and 500-mg cohorts; bosutinib was well tolerated with no DLTs. Five patients were initially enrolled in the 600-mg cohort; one patient developed grade 3 rash, nausea, and vomiting (qualified as a DLT), and another had grade 2 alanine transaminase (ALT) elevation that resolved spontaneously after 69 days, without dose interruption. The 600-mg cohort was expanded to 12 patients, with one patient each reporting grade 2 rash (worsening at time of treatment interruption) and grade 3 diarrhea (despite medical therapy). Because of the clinical benefit observed at all doses and the observed events at the 600-mg dose level, 500 mg of bosutinib was chosen as the starting dose for part 2 despite not reaching a protocol-defined MTD.

Dose intensity (parts 1 and 2)

The median duration of bosutinib treatment (parts 1 and 2) was 14.9 months (range, 0.2-49.2 months), including 14.9 months for imatinib-resistant patients and 15.3 months for imatinib-intolerant patients. The median dose intensity for imatinib-resistant and imatinib-intolerant patients was 484.9 mg/d and 394.1 mg/d, respectively. Treatment interruptions because of AEs were required by 189 of 288 (66%) patients (121/200 [61%] imatinib-resistant and 68/88 [77%] imatinib-intolerant patients); the median duration of treatment interruptions because of AEs was 21 days (range, 1-308 days). Dose reductions because of AEs were required by 135 of 288 (47%) patients (86/200 [43%] imatinib-resistant and 49/88 [56%] imatinib-intolerant patients). Common AEs (all grades) leading to dose reductions included thrombocytopenia (n = 33; 11%), rash (n = 21; 7%), and diarrhea (n = 13; 5%). The median number of treatment interruptions for any reason was 2 (range, 1-37 interruptions) in the imatinib-resistant group and 2 (range, 1-49 interruptions) in the imatinib-intolerant group, resulting in a median of 4% and 10% of days with treatment interruption, respectively. Among patients initially treated with bosutinib 400 or 500 mg/d, 29 of 189 (15%) imatinib-resistant and 3 of 88 (3%) imatinib-intolerant patients had their dose of bosutinib escalated to 600 mg/d.

Efficacy

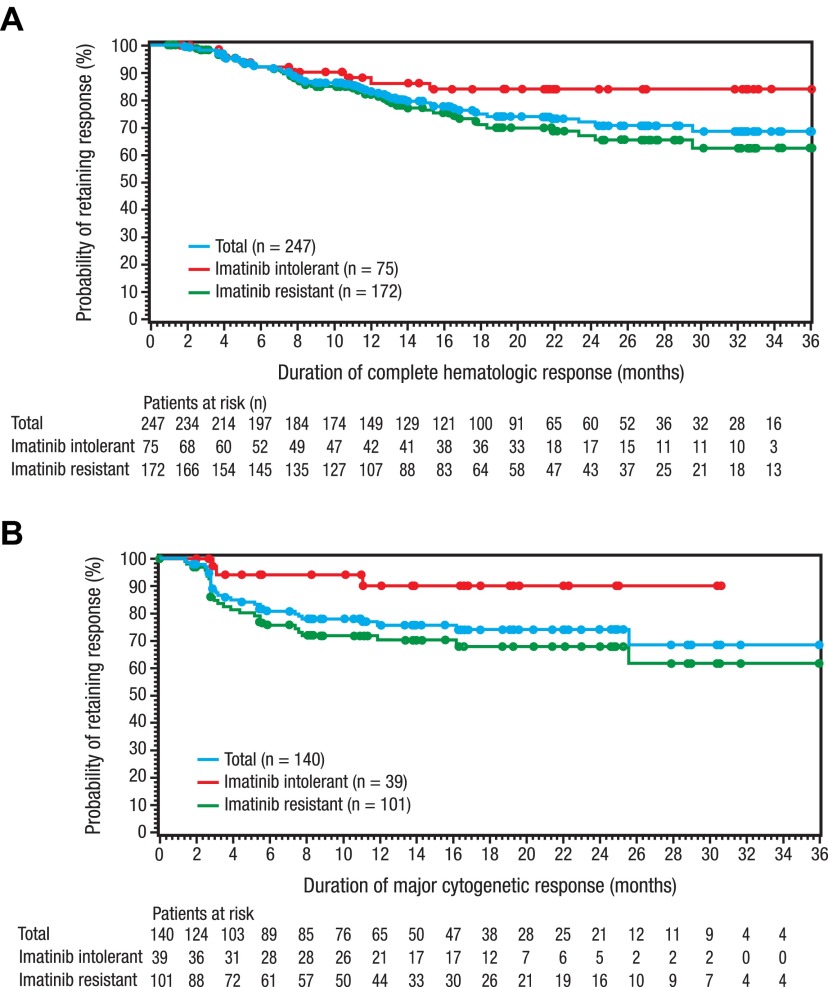

Most patients (n = 247/287 [86%]) in the evaluable population for hematologic response achieved a CHR (Table 2), with a median time to CHR of 2.0 weeks among responders. Among 141 evaluable patients without CHR at baseline, 110 (78%) achieved a CHR during the study. The duration of CHR is shown in Figure 2A.

Table 2.

Hematologic response

| Response | Imatinib resistant |

Imatinib intolerant |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Cumulative response | ||||||

| Evaluable patients | 199 | 88 | 287 | |||

| Complete response | 172 | 86 | 75 | 85 | 247 | 86 |

| Cumulative response among patients with no baseline complete hematologic response | ||||||

| Evaluable patients | 100 | 41 | 141 | |||

| Complete response | 76 | 76 | 34 | 83 | 110 | 78 |

| Reason for exclusion from analysis | ||||||

| No baseline assessment | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

Figure 2.

Duration of CHR and MCyR with bosutinib treatment. Duration of CHR (A) and MCyR (B) were determined by the evaluable population; patients entering the study in CCyR were excluded. As of the data cutoff, 77% of the evaluable patients who achieved a CHR still retained their response (124/172 [72%] imatinib-resistant and 65/75 [87%] imatinib-intolerant patients), with a median duration of CHR not reached. Of the evaluable patients who achieved a MCyR, 78% still retained their MCyR as of the data cutoff (73/101 [72%] imatinib-resistant and 36/39 [92%] imatinib-intolerant patients), with the median duration of MCyR not reached.

At 24 weeks, 31% (95% CI, 26%-37%) of all treated patients achieved a MCyR, including 33% (95% CI, 27%-40%) imatinib-resistant and 27% (95% CI, 18%-38%) imatinib-intolerant patients (Table 3). Overall, 53% of evaluable patients achieved a MCyR during the study, and 41% achieved a CCyR. Among responders, median time to MCyR was 12.3 weeks and was similar between imatinib-resistant (13.1 weeks) and imatinib-intolerant (12.1 weeks) patients. The duration of MCyR is shown in Figure 2B. Dose intensities of > 350 mg/d were associated with greater rates of MCyR (Table 3). Of those patients who had not previously achieved MCyR on imatinib, 41% and 25% achieved MCyR and CCyR, respectively, on bosutinib (Table 4).

Table 3.

Cytogenetic response

| Response | Imatinib resistant |

Imatinib intolerant |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Response at 24 weeks | ||||||

| All treated patients* | 200 | 88 | 288 | |||

| Major† | 66 | 33 | 24 | 27 | 90 | 31 |

| Complete | 45 | 23 | 20 | 23 | 65 | 23 |

| Cumulative response | ||||||

| Evaluable patients | 186 | 80 | 266 | |||

| Major† | 101 | 54 | 39 | 49 | 140 | 53 |

| Complete | 77 | 41 | 33 | 41 | 110 | 41 |

| Reason for exclusion from evaluable analysis | ||||||

| No baseline assessment | 14 | 8 | 22 | |||

| Major cytogenetic response† in evaluable patients by dose intensity | ||||||

| Mean dose < 250 mg/d | 1/6 | 17 | 0/6 | 0 | 1/12 | 8 |

| Mean dose 250 to < 350 mg/d | 12/24 | 50 | 9/17 | 53 | 21/41 | 51 |

| Mean dose 350 to < 450 mg/d | 26/45 | 58 | 12/21 | 57 | 38/66 | 58 |

| Mean dose 450 to < 550 mg/d | 53/94 | 56 | 18/36 | 50 | 71/130 | 55 |

| Mean dose ≥ 550 mg/d | 9/17 | 53 | 0/0 | 0 | 9/17 | 53 |

Patients without a baseline or week 24 assessment were counted as nonresponders.

Major cytogenetic response = complete + partial cytogenetic response.

Table 4.

Cytogenetic response by best previous response to imatinib

| Response | Imatinib resistant |

Imatinib intolerant |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Best previous cytogenetic response with imatinib* | ||||||

| Major cytogenetic response† | 80 | 40 | 39 | 44 | 119 | 41 |

| Complete | 51 | 26 | 31 | 35 | 82 | 28 |

| Partial | 29 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 37 | 13 |

| No major cytogenetic response | 106 | 53 | 23 | 26 | 129 | 45 |

| Minor | 15 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 6 |

| Minimal | 24 | 12 | 6 | 7 | 30 | 10 |

| None | 67 | 34 | 14 | 16 | 81 | 28 |

| Missing | 14 | 7 | 26 | 30 | 40 | 14 |

| Major cytogenetic response† by best previous response to imatinib | ||||||

| Major cytogenetic response on imatinib previously | 51/80 | 64 | 18/39 | 46 | 69/119 | 58 |

| No major cytogenetic response on imatinib previously | 45/106 | 42 | 8/23 | 35 | 53/129 | 41 |

| Missing data on response to imatinib previously | 5/14 | 36 | 13/26 | 50 | 18/40 | 45 |

| Complete cytogenetic response by best previous response to imatinib | ||||||

| Major cytogenetic response on imatinib previously | 46/80 | 58 | 17/39 | 44 | 63/119 | 53 |

| No major cytogenetic response on imatinib previously | 27/106 | 25 | 5/23 | 22 | 32/129 | 25 |

| Missing data on response to imatinib previously | 4/14 | 29 | 11/26 | 42 | 15/40 | 38 |

Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding.

Major cytogenetic response = complete + partial cytogenetic response.

Among patients who achieved a CCyR and were evaluable for molecular response, 64% (n = 35/55) of imatinib-resistant and 65% (n = 15/23) of imatinib-intolerant patients achieved a MMR; 49% (n = 27/55) and 61% (n = 14/23) achieved a CMR, respectively (Table 5). An analysis of molecular response in all treated patients who excluded only those patients enrolled in countries (China, India, Russia, and South Africa) in which molecular response was not assessed was also performed; in this analysis the MMR rate was 41% and the CMR rate was 34%.

Table 5.

Molecular response among patients achieving complete cytogenetic response

| Response | Imatinib resistant |

Imatinib intolerant |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Cumulative response* | ||||||

| Patients in subgroup analysis | 55 | 23 | 78 | |||

| Major | 35 | 64 | 15 | 65 | 50 | 64 |

| Complete | 27 | 49 | 14 | 61 | 41 | 53 |

| Reason for exclusion from analysis | ||||||

| No assessment† | 70 | 21 | 91 | |||

| Did not achieve complete cytogenetic response | 75 | 44 | 119 | |||

Major molecular response = ≥ 3 log reduction from standardized baseline Bcr-Abl:Abl ratio. Complete molecular response = undetectable Bcr-Abl, with a sensitivity of ≥ 5 log. Molecular response was not assessed according to the International Scale.

Because of logistical constraints, 4 countries (China, India, Russia, and South Africa) did not evaluate molecular response.

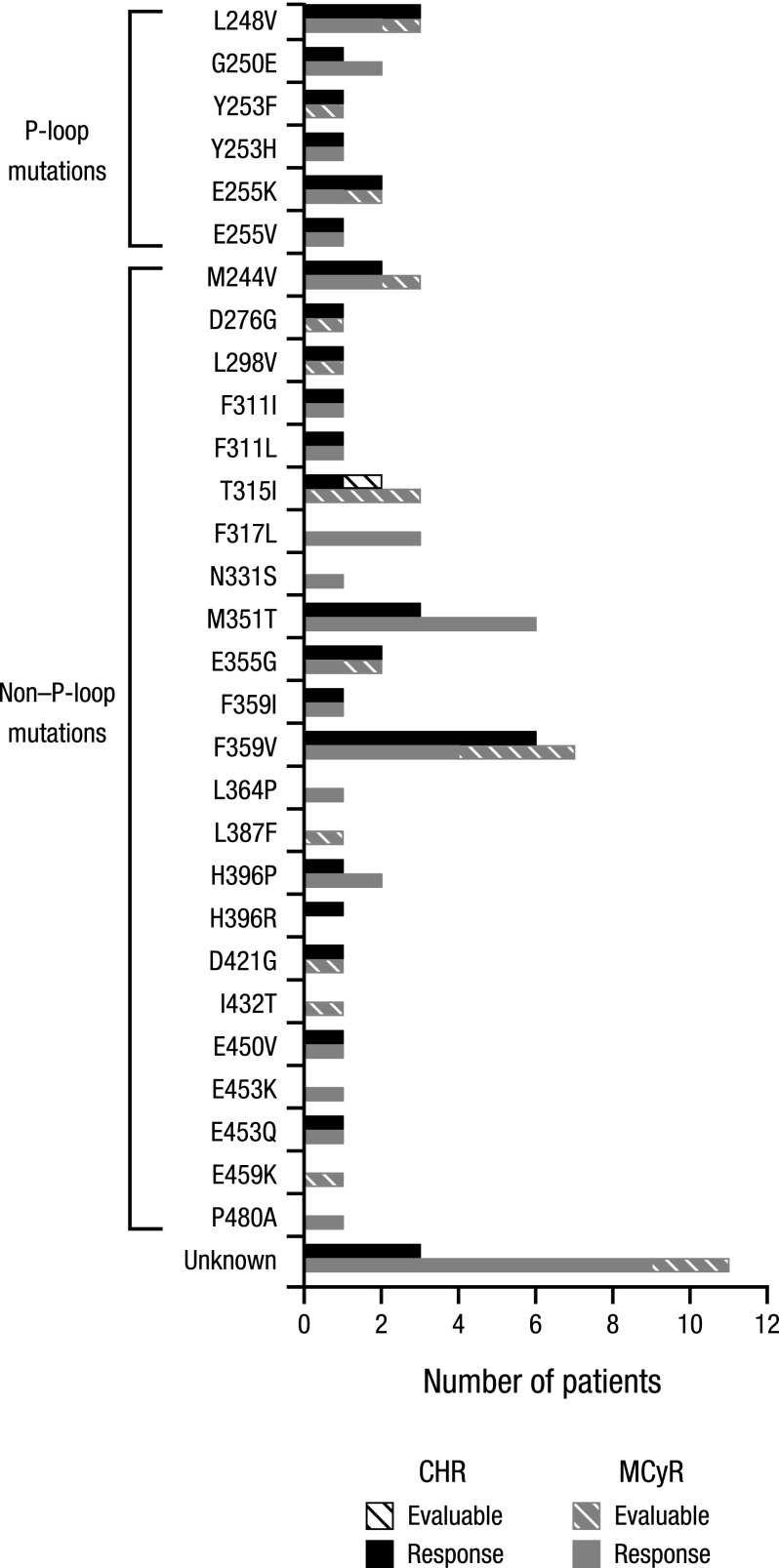

Among the 115 patients with known mutations at baseline, the most common were M351T (n = 7), F359V (n = 7), F317L (n = 4), L248V (n = 4), G250E (n = 3), M244V (n = 3), and T315I (n = 3). Similar rates of CHR or MCyR were observed between patients with and without mutations. Responses were observed broadly across Bcr-Abl mutants, except for T315I (Figure 3 and supplemental Table 3).

Figure 3.

CHR and MCyR by Bcr-Abl mutation status at baseline. Mutations indicated as “unknown” included abnormalities not associated with known mutations (eg, nucleotide insertions or deletions, alternate splicing).

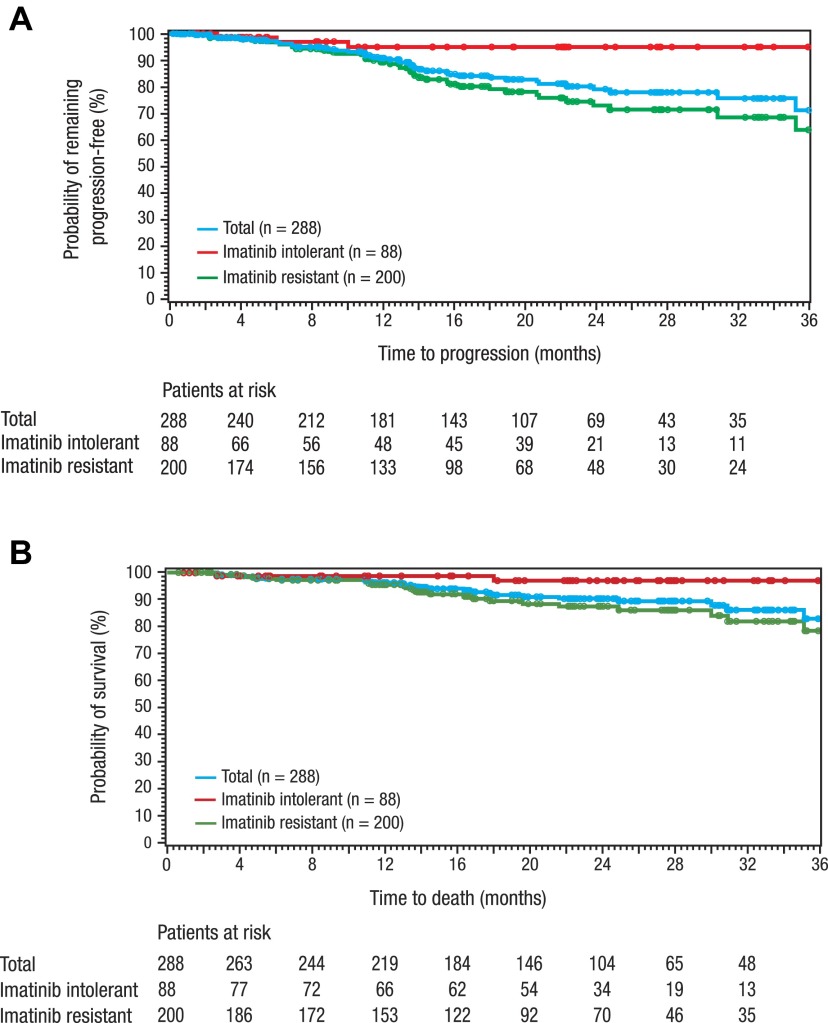

At 1 year, the PFS rate was 91%, including 89% of imatinib-resistant and 95% of imatinib-intolerant patients; at 2 years, the PFS rate was 79%, including 73% of imatinib-resistant and 95% of imatinib-intolerant patients (Figure 4A). Overall survival was 97% at 1 year and 92% at 2 years, including 89% for imatinib-resistant and 98% for imatinib-intolerant patients at 2 years (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

PFS and overall survival with bosutinib treatment. PFS (A) and overall survival (B) are shown for chronic phase imatinib-resistant or -intolerant patients treated with bosutinib (all-treated population) at a median follow-up of 24.2 months.

Safety

The most common nonhematologic treatment-emergent AEs were diarrhea (84%), nausea (44%), rash (44%), and vomiting (35%; Table 6). These events occurred early (median time to onset of 2.0, 5.0, 17.5, and 8.0 days, respectively), were generally transient (median cumulative duration of 23.0, 9.5, 25.0, and 3.0 days, respectively), and frequently resolved spontaneously or with supportive care and/or dose adjustments. Of the 243 patients who experienced diarrhea, 165 (68%) patients received concomitant medication, including 141 (58%) who received loperamide and 9 (4%) who received diphenoxylate/atropine. Overall, grade 3 diarrhea was experienced by 26 (9%) of patients (Table 6), with a median event duration of 3.0 days; no grade 4 events were reported. Of those who experienced diarrhea, 13 (5%) patients required dose reduction, and 6 (3%) patients discontinued treatment because of diarrhea. Of the 35 (14%) patients who required dose interruption for diarrhea, 33 were rechallenged with bosutinib, and 31 of 33 (94%) did not have another diarrhea event and/or did not discontinue permanently because of diarrhea. Less-common AEs included fluid retention (15%; all but one event were grade 1/2), pleural effusion (4%), and muscle-related AEs (muscle spasms [3%], musculoskeletal pain [3%], creatine kinase elevations [2%], and myalgia [5%]). Two cases of hypopigmentation were reported.

Table 6.

Treatment-emergent adverse events and laboratory abnormalities

| Event | Imatinib resistant (n = 200) |

Imatinib intolerant (n = 88) |

Total (N = 288) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

Gr 3/4 |

All |

Gr 3/4 |

All |

Gr 3/4 |

|||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Nonhematologic TEAEs occurring with any grade in 10% or more of patients | ||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 169 | 85 | 15 | 8 | 74 | 84 | 11 | 13 | 243 | 84 | 26 | 9 |

| Nausea | 84 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 50 | 4 | 5 | 128 | 44 | 4 | 1 |

| Rash* | 85 | 43 | 17 | 9 | 41 | 47 | 9 | 10 | 126 | 44 | 26 | 9 |

| Vomiting | 67 | 34 | 3 | 2 | 34 | 39 | 6 | 7 | 101 | 35 | 9 | 3 |

| Abdominal pain | 44 | 22 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 24 | 1 | 1 | 65 | 23 | 3 | 1 |

| Upper abdominal pain | 38 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 42 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 64 | 22 | 2 | 1 |

| Pyrexia | 48 | 24 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 21 | 1 | < 1 |

| Cough | 34 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 29 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Edema† | 28 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 15 | 1 | < 1 |

| Arthralgia | 26 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 39 | 14 | 1 | < 1 |

| Decreased appetite | 25 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| Constipation | 17 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 11 | 1 | < 1 |

| Back pain | 12 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 19 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Hematologic laboratory abnormalities (all grades) | ||||||||||||

| Anemia‡ | 182 | 91 | 20 | 10 | 76 | 86 | 16 | 18 | 258 | 90 | 36 | 13 |

| Thrombocytopenia§ | 131 | 66 | 39 | 20 | 60 | 68 | 29 | 33 | 191 | 66 | 68 | 24 |

| Neutropenia¶ | 74 | 37 | 28 | 14 | 42 | 48 | 25 | 28 | 116 | 40 | 53 | 18 |

| Other laboratory abnormalities occurring with grade 3/4 severity in 4% or more of patients | ||||||||||||

| Elevated ALT | 111 | 56 | 20 | 10 | 58 | 66 | 10 | 11 | 169 | 59 | 30 | 10 |

| Elevated AST | 95 | 48 | 8 | 4 | 46 | 52 | 6 | 7 | 141 | 49 | 14 | 5 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 88 | 44 | 18 | 9 | 36 | 41 | 6 | 7 | 124 | 43 | 24 | 8 |

| Elevated uric acid | 89 | 45 | 12 | 6 | 31 | 35 | 5 | 6 | 120 | 42 | 17 | 6 |

| Hypocalcemia | 75 | 38 | 5 | 3 | 40 | 45 | 5 | 6 | 115 | 40 | 10 | 3 |

| Elevated lipase | 50 | 25 | 18 | 9 | 29 | 33 | 6 | 7 | 79 | 27 | 24 | 8 |

| Hypermagnesemia | 47 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 26 | 30 | 18 | 20 | 73 | 25 | 34 | 12 |

| Elevated INR | 52 | 26 | 3 | 2 | 19 | 22 | 4 | 5 | 71 | 25 | 7 | 2 |

| Hypomagnesemia | 44 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 19 | 1 | 0 |

ALT indicates alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Gr, grade; INR, international normalized ratio; and TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Rash includes acne, allergic dermatitis, erythema, exfoliative rash, folliculitis, heat rash, rash, rash erythematous, rash macular, rash papular, rash pruritic, and skin exfoliation.

Edema includes edema, face edema, localized edema, edema peripheral, periorbital edema, and pitting edema.

At baseline, anemia was reported by 125 (63%) imatinib-resistant patients and 45 (51%) imatinib-intolerant patients.

At baseline, thrombocytopenia was reported by 34 (17%) imatinib-resistant patients and 19 (22%) imatinib-intolerant patients.

At baseline, neutropenia was reported by 18 (9%) imatinib-resistant patients and 13 (15%) imatinib-intolerant patients.

Possibly drug-related cardiac events were observed in 5% of patients and included angina pectoris (n = 3), cardiac failure (n = 2), and atrial fibrillation, biatrial enlargement, bradycardia, coronary artery stenosis, left ventricular dysfunction, prolonged QT interval, palpitations, pericardial effusion, and premature atrial beat (n = 1 each). On treatment (all time points) and at treatment completion, only one patient had a Fridericia-corrected QT interval (QTcF) interval of > 500 ms, and one patient had an increase of ≥ 60 ms. At baseline, 3% of patients had a QTcF interval > 450 ms, but none had an interval > 500 ms. All events of QTcF prolongation were asymptomatic.

Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities were thrombocytopenia (24%), neutropenia (18%), and anemia (13%; Table 6). Myelosuppression generally occurred early (median time to onset of 29 days [range, 1-845 days]), with a median duration for grade 3/4 events of 36 days (range, 5-537 days). Three patients resistant to imatinib experienced grade 3 hemorrhagic AEs (any causality); all events were in the context of concurrent thrombocytopenia. Drug-related hemorrhagic AEs of any grade were reported by 5 (2%) patients, including 2 imatinib-resistant and 3 imatinib-intolerant patients.

On-treatment grade 3/4 elevations of ALT and aspartate transaminase (AST) were experienced by 10% and 5% of patients, respectively, with incidence rates similar between imatinib-resistant and imatinib-intolerant patients (Table 6). For those patients who experienced transaminase elevations (any grade), median time to onset was 28 days for ALT and 22 days for AST.

Twenty-one percent of patients discontinued treatment because of AEs, including 17% of imatinib-resistant and 31% of imatinib-intolerant patients, with a median time to discontinuation because of AEs of 5.3 months (range, 0.2-19.7 months) and 3.8 months (range, 0.5-12.9 months), respectively. AEs most frequently leading to discontinuation included thrombocytopenia (4%), increased ALT (2%), increased AST (2%), and diarrhea (2%; Figure 1).

In retrospective evaluation of cross-intolerance between bosutinib and imatinib we found that 27% of patients with intolerance to imatinib experienced the same grade 3/4 AE on bosutinib and 6% discontinued bosutinib because of the same AE. Of these, 15 of 31 patients with intolerance to imatinib related to myelosuppression experienced grade 3/4 myelosuppression on bosutinib; 13% discontinued because of myelosuppression. Three of 10 patients with intolerance to imatinib related to rash experienced a grade 3/4 rash on bosutinib. Only 1 patient each with intolerance to imatinib related to diarrhea and muscle spasms experienced these grade 3/4 AEs on bosutinib. No patient with intolerance to imatinib related to other gastrointestinal events, edema, fatigue, or hepatobiliary disorders experienced the same grade 3/4 AE on bosutinib.

Pharmacokinetics

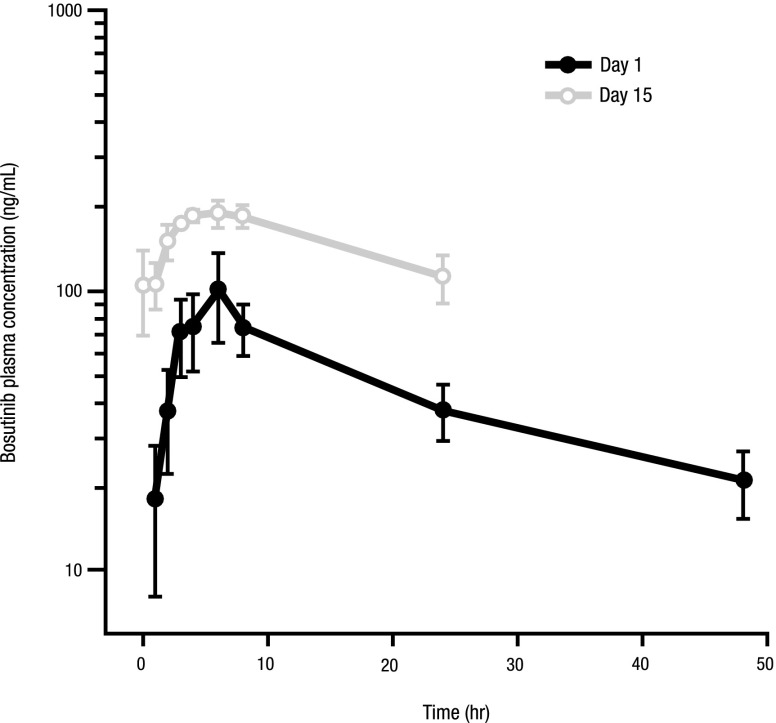

Pharmacokinetic data for bosutinib from part 1 of the study (400 mg [n = 3], 500 mg [n = 3], and 600 mg [n = 12]; Table 7) indicated that absorption was relatively slow, with a median time to maximum drug concentration of ∼ 3-6 hours. There was no increase in plasma exposure when the dose of bosutinib increased from 500-600 mg, which could be explained by the saturable solubility of bosutinib at greater doses. Multiple-dose exposure was ∼ 2-fold greater than single-dose exposure (Figure 5). The elimination half-life (22-27 hours) of bosutinib supports a once-daily dosing regimen. The coefficients of variation for maximum concentration and area under the curve were small to moderate.

Table 7.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters on days 1 and 15 after oral administration of bosutinib 400, 500, and 600 mg

| Dose | Day | Measure | Cmax, ng/mL | Tmax, h* | T1/2, h | AUC, ng·h/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 mg | 1 | No. | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean | 77.2 | 3.0 (3-4) | NA | 1487 | ||

| CV% | 76.3 | 17.3 | 109.4 | 72.2 | ||

| 15 | No. | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| Mean | 157.3 | 6.0 (6-24) | 22.6 | 2851 | ||

| CV% | 17.6 | 86.6 | 24.4 | 16.6 | ||

| 500 mg | 1 | No. | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean | 100.9 | 6.0 (6-6) | 22.1 | 2064 | ||

| CV% | 35.3 | 0 | 10.1 | 24.8 | ||

| 15 | No. | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| Mean | 200.3 | 6.0 (4-8) | 21.9 | 3660 | ||

| CV% | 6.0 | 33.3 | 27.9 | 11.4 | ||

| 600 mg | 1 | No. | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| Mean | 119.9 | 4.0 (2-48) | 24.7 | 2074 | ||

| CV% | 33.5 | 159.0 | 54.1 | 20.0 | ||

| 15 | No. | 10 | 10 | 6 | 10 | |

| Mean | 208.2 | 6.0 (3-8) | 27.0 | 3360 | ||

| CV% | 35.2 | 30.4 | 100.8 | 43.5 |

AUC indicates area under the curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; CV%, coefficient of variation; NA, not available; Tmax, time to maximum concentration; and T1/2, elimination half life.

For Tmax, median (range) values are shown instead of mean values.

Figure 5.

Mean plasma concentration vs time profiles after oral administration of bosutinib 500 mg on days 1 and 15.

Discussion

In the current study, bosutinib demonstrated efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in patients with CP CML with imatinib resistance or intolerance and no other previous TKI exposure. As predicted on the basis of preclinical data,17 bosutinib was effective in both imatinib-resistant and imatinib-intolerant patients across all Bcr-Abl mutations, except the T315I mutation. Individual dose intensities of ≥ 350 mg/d were associated with an increased rate of MCyR, suggesting a dose-intensity threshold for best observed response.

The majority (86%) of evaluable patients achieved a CHR, including 78% of patients without a CHR at baseline. In addition, more than one-half (53%) of evaluable patients achieved a MCyR, with 31% of all treated patients achieving a MCyR at 24 weeks. Further, most (78%) evaluable patients who achieved a MCyR during the study still retained their response as of the cutoff date for this analysis, indicating good durability of cytogenetic response to bosutinib.

CCyR was observed in 41% of evaluable imatinib-resistant and imatinib-intolerant patients. Among patients with a CCyR who were evaluable for molecular response, 64% achieved a MMR, including 53% with a CMR; however, it should be noted that molecular response was not evaluated by use of the International Scale because this scale was not in wide use at the time the study was designed. In addition, molecular response was evaluable only in a small subset of patients. In an all-treated analysis that included patients regardless of achievement of a CCyR, the rate of MMR was 41% (CMR, 34%) of all patients treated, except those patients enrolled in the 4 countries (China, India, Russia, and South Africa) in which molecular response was not assessed.

When we allowed for differences in study design and patient population, we found the efficacy outcomes from this study are comparable with those observed with dasatinib6–9,15 and nilotinib3,10 in imatinib-resistant and imatinib-intolerant patients with CP CML. In phase 2 studies of dasatinib, a CHR was achieved in 86%-92% of patients and a MCyR was achieved in 52%-59% of patients after a follow-up time of 6-8 months.7,9 Similar results are reported for nilotinib (CHR, 74%; MCyR, 35%-48%) after a follow-up time of 6 months, with comparable results for imatinib-resistant and imatinib-intolerant patients.3,10 Responses with these agents increased over time, with MCyR rates improving from 45% with dasatinib and 48% with nilotinib after a median follow-up of 6 months3,6 to 53% and 58%, respectively, after ∼ 2 years.15,24 Longer follow-up will be required to determine the ultimate response rate with bosutinib.

Results of this study suggest that bosutinib has a favorable safety profile. Myelosuppression generally occurred early, was mild to moderate in intensity, and was transient. Incidence rates of on-therapy grade 3/4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were 18% and 24%, respectively, with bosutinib in this study compared with 33%-49% and 22%-47%, respectively, reported for dasatinib6–9 and 13%-29% and 20%-29%, respectively, reported for nilotinib.3,10 Three patients reported grade 3/4 hemorrhagic events (with concurrent thrombocytopenia) that subsequently resolved. Because c-KIT has a role in normal hematopoiesis, the absence of inhibition of c-KIT by bosutinib might mitigate the risk of myelosuppression.21 The authors of several reports have shown that other TKIs inhibit platelet function, particularly dasatinib,25–27 whereas there is little evidence of a bosutinib effect on platelet function.25 Consistent with these observations, bleeding has been reported in 40% of patients treated with dasatinib, 10% of which were grade 3/4,25,28 whereas in contrast only 5% of patients (1% with grade 3) experienced hemorrhagic events in this study. Together, these data suggest bosutinib has an acceptable hematologic toxicity profile and is not associated with a risk of bleeding.

The incidence of nonhematologic AEs was acceptable with bosutinib. Although diarrhea was quite common (84% of patients), most instances were mild, transient, and manageable, frequently resolving spontaneously or with a combination of supportive care and/or dose adjustment after approximately 3 weeks of therapy; few patients (3%) discontinued therapy because of diarrhea. Skin hypopigmentation has been reported for imatinib,29 perhaps because of inhibition of c-KIT, and was observed in 2 patients in the current study. Fluid retention, a troublesome nonhematologic toxicity associated with dasatinib (pleural effusion in 23% of patients; 4% with grade 3/4)6–9,30–32 and imatinib (peripheral edema),31,33 occurred relatively infrequently with bosutinib. Pleural effusion of any severity grade was reported in 4% of patients treated with bosutinib, with only one event of grade 3/4 severity reported.

Muscle cramps, musculoskeletal pain, creatine kinase elevations, and myalgia have been reported in up to 50% of patients during imatinib treatment31,33,34 but were infrequent with bosutinib. Bosutinib was associated with minimal effects on the QTcF interval; only 2 patients experienced an on-treatment QTcF interval > 500 ms or an increase of ≥ 60 ms. These data are supported by a recent thorough QTc study in which the authors also showed no effect of bosutinib on QTc prolongation.35 Nilotinib has occasionally been associated with QTcF interval prolongation (typically 5-15 ms; 1%-4% with QTcF interval > 500 ms or increase > 60 ms) and sudden/cardiac death (< 1%).3,10,36,37 Although liver laboratory abnormalities of any grade were common, on-treatment grade 3/4 ALT and AST elevations were each experienced by 10% or fewer patients. Not surprisingly, a greater percentage of imatinib-intolerant (31%) than imatinib-resistant (17%) patients discontinued therapy because of AEs, most commonly thrombocytopenia in both groups. Nonetheless, a discontinuation rate of 31% in patients with previous intolerance to imatinib provides indirect evidence of limited cross-intolerance to bosutinib.

In conclusion, these data suggest bosutinib is effective, with an acceptable safety profile that is differentiated from that of other TKIs, and may offer a new treatment option for patients with CP CML who are resistant or intolerant to imatinib. Results of this study support continued investigation of bosutinib for the treatment of Ph+ CML. Clinical evaluations of bosutinib in the settings of newly diagnosed CP CML, CP CML after failure of 2 or more TKIs, and accelerated phase and blast phase CML are currently ongoing.38

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Becker Hewes in initiation and conduct of this study.

This study was sponsored by Wyeth Research, which was acquired by Pfizer Inc in October 2009. Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Kimberly Brooks, PhD, at a MedErgy HealthGroup company, and was funded by Pfizer.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Presented in part in abstract form at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL, December 9-12, 2006; annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, June 1-5, 2007; annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, December 11, 2007; annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 30-June 3, 2008; annual congress of the European Hematology Association, Copenhagen, Denmark, June 12-15, 2008; annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 6, 2008; annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, June 7, 2010; annual congress of the European Hematology Association, Barcelona, Spain, June 10-13, 2010; and annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL, December 6, 2010.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.E.C., H.J.K., and C.G.-P. created and designed the study; J.E.C., H.M.K., T.H.B., D.-W.K., A.G.T., Z.-X.S., R.P., H.J.K., and C.G.-P. provided study materials or patients; J.E.C., T.H.B., D.-W.K., and J.W. collected and assembled data; all authors assisted in the analysis and/or interpretation of the data; all authors assisted in writing and critically revising the manuscript; and all authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.E.C., H.M.K., T.H.B., H.J.K., and C.G.-P. have served as advisors for Pfizer Inc; T.H.B. has also served as an advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. J.E.C. and H.M.K. have received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc; T.H.B. has received research funding from Novartis; and C.G.-P. has received research funding from Pfizer Inc. T.H.B. has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc; and D.-W.K. has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. S.A., A.V, N.B., R.A., J.W., and E.L. are employees of Pfizer Inc; S.A., R.A., and J.W. are also stockholders of Pfizer Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jorge E. Cortes, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard, Box 428, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: jcortes@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. V. 2.2009. [Accessed May 12, 2009]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/cml.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures, 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian HM, Giles F, Gattermann N, et al. Nilotinib (formerly AMN107), a highly selective BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is effective in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase following imatinib resistance and intolerance. Blood. 2007;110(10):3540–3546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Deininger M, et al. Dasatinib induces durable cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Leukemia. 2008;22(6):1200–1206. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lavallade H, Apperley JF, Khorashad JS, et al. Imatinib for newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: incidence of sustained responses in an intention-to-treat analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3358–3363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2531–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochhaus A, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, et al. Dasatinib induces notable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of imatinib therapy. Blood. 2007;109(6):2303–2309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian H, Pasquini R, Hamerschlak N, et al. Dasatinib or high-dose imatinib for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of first-line imatinib: a randomized phase 2 trial. Blood. 2007;109(12):5143–5150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah NP, Kantarjian HM, Kim DW, et al. Intermittent target inhibition with dasatinib 100 mg once daily preserves efficacy and improves tolerability in imatinib-resistant and -intolerant chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3204–3212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2542–2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408–2417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez P, Dipersio JF. Therapy options in imatinib failures. Oncologist. 2008;13(4):424–434. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisberg E, Manley PW, Cowan-Jacob SW, Hochhaus A, Griffin JD. Second generation inhibitors of BCR-ABL for the treatment of imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(5):345–356. doi: 10.1038/nrc2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantarjian H, Pasquini R, Levy V, et al. Dasatinib or high-dose imatinib for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia resistant to imatinib at a dose of 400 to 600 milligrams daily: two-year follow-up of a randomized phase 2 study (START-R). Cancer. 2009;115(18):4136–4147. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian HM, Giles FJ, Bhalla KN, et al. Nilotinib is effective in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after imatinib resistance or intolerance: 24-month follow-up results. Blood. 2011;117(4):1141–1145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-277152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puttini M, Coluccia AM, Boschelli F, et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of SKI-606, a novel Src-Abl inhibitor, against imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl+ neoplastic cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(23):11314–11322. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golas JM, Arndt K, Etienne C, et al. SKI-606, a 4-anilino-3-quinolinecarbonitrile dual inhibitor of Src and Abl kinases, is a potent antiproliferative agent against chronic myelogenous leukemia cells in culture and causes regression of K562 xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63(2):375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remsing Rix LL, Rix U, Colinge J, et al. Global target profile of the kinase inhibitor bosutinib in primary chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):477–485. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konig H, Holyoake TL, Bhatia R. Effective and selective inhibition of chronic myeloid leukemia primitive hematopoietic progenitors by the dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor SKI-606. Blood. 2008;111(4):2329–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartolovic K, Balabanov S, Hartmann U, et al. Inhibitory effect of imatinib on normal progenitor cells in vitro. Blood. 2004;103(2):523–529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redaelli S, Piazza R, Rostagno R, et al. Activity of bosutinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib against 18 imatinib-resistant BCR/ABL mutants. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):469–471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, et al. Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;108(6):1809–1820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantarjian HM, Giles F, Bhalla KN, et al. Nilotinib in chronic myeloid leukemia patients in chronic phase (CMLCP) with imatinib resistance or intolerance: 2-year follow-up results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2008;112(suppl) Abstract 3238. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quintás-Cardama A, Han X, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced platelet dysfunction in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(2):261–263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman DK. The Y's that bind: negative regulators of Src family kinase activity in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gratacap MP, Martin V, Valera MC, et al. The new tyrosine-kinase inhibitor and anti-cancer drug dasatinib reversibly affects platelet activation in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;114(9):1884–1892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brave M, Goodman V, Kaminskas E, et al. Sprycel for chronic myeloid leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia resistant to or intolerant of imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(2):352–359. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(3):228–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, et al. Pleural effusion in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with dasatinib after imatinib failure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3908–3914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gora-Tybor J, Robak T. Targeted drugs in chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(29):3036–3051. doi: 10.2174/092986708786848578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SPRYCEL (dasatinib) tablet for oral use [package insert] Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.GLEEVEC (imatinib mesylate) tablets for oral use [package insert] East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franceschino A, Tornaghi L, Benemacher V, Assouline S, Gambacorti-Passerini C. Alterations in creatine kinase, phosphate and lipid values in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia during treatment with imatinib. Haematologica. 2008;93(2):317–318. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbas R, Hug B, Leister C, Burns J, Sonnichsen D. A single dose, crossover, placebo- and moxifloxacin-controlled study to assess the effects of bosutinib (SKI-606) on cardiac repolarization in healthy adult subjects.. Poster presented at the 15th Congress of the European Hematology Association; June 12, 2010; Barcelona, Spain. Abstract 0846. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tasigna (nilotinib) [package insert] East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.le Coutre P, Ottmann OG, Giles F, et al. Nilotinib (formerly AMN107), a highly selective BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is active in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant accelerated-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(4):1834–1839. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller G, Schafhausen P, Brummendorf TH. Bosutinib: a novel dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor. In: Martens UM, editor. Small Molecules in Oncology, Recent Results in Cancer Research. Vol 184. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]