Abstract

Introduction

There is a high incidence of blood transfusion following hip fractures in elderly patients. Tranexamic acid (TXA) has proven efficacy in decreasing blood loss in general trauma patients as well as patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery. A randomised controlled trial will measure the effect of TXA in a population of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.

Methods

This is a double-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Patients admitted through the emergency room that are diagnosed with an intertrochanteric or femoral neck fracture will be eligible for enrolment and randomised to either treatment with 1 g of intravenous TXA or intravenous saline at the time of skin incision. Patients undergoing percutaneous intervention for non-displaced or minimally displaced femoral neck fractures will not be eligible for enrolment. Postoperative transfusion rates will be recorded and blood loss will be calculated from serial haematocrits.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and is registered with clinicaltrials.gov. The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

Keywords: tranexamic acid, hip fracture, blood transfusion

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled trial is the optimal study design to address the question of efficacy of tranexamic acid (TXA) use in patients with hip fractures.

The outcomes will be reported based on 1-year follow-up, which is longer follow-up than any other study examining TXA use in patients with hip fractures.

Findings will provide objective data from which clinicians can base future guidelines regarding TXA administration.

Recruitment is slow as patients and healthcare proxies are wary of enrolling in a study in a trauma setting.

Introduction

Hip fractures in the elderly remain a pressing public health issue in the USA given the aging population.1 Hip fractures are associated with numerous adverse events and increased mortality up to 1 year after the event.2–5 Hidden blood loss in hip fractures, in addition to intraoperative blood loss, may be as high as 1500 cc.6 7 The rate of blood transfusion in the perioperative period for hip fracture patients is reported between 20% and 60%.8–11 Total blood loss, and thus rate of transfusion, is greater for extracapsular hip fractures compared to intracapsular hip fractures.6 A meta-analysis of 20 studies found a significantly increased risk of postoperative bacterial infection in patients who receive an allogenic blood transfusion in the perioperative period.12 In addition to the increased risk of infection, patients who require blood transfusion following hip fracture have an increased hospital length of stay.13 Furthermore, an allogenic blood transfusion in the USA was recently estimated to increase costs by $1731 per admission.14

Numerous antifibrinolytics have been used to limit bleeding in orthopaedic surgery and prevent the need for blood transfusion.15–19 One of these antifibrinolytics, tranexamic acid (TXA), is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid lysine and acts as a competitive inhibitor in the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, therefore preventing the degradation of fibrin. As a result of the CRASH-2 trial,20 21 which demonstrated reduced mortality in trauma patients who received TXA, the WHO added TXA to the essential drugs list. Currently TXA is not routinely used in patients with hip fractures in the USA, despite its common use worldwide and proven efficacy in reducing blood loss in other populations.

Numerous studies have investigated the safety and efficacy of TXA in patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery, including total joint replacement and spine surgery.22–27 The consensus from this literature is overwhelmingly in favour of administration of TXA given the decrease in blood loss, transfusion rates and cost.28 29 Although several individual studies have found increased risk of thromboembolic events in groups receiving TXA,9 30 larger studies and meta-analyses have uniformly found no increased risk of thrombosis.31 32

Patients who suffer hip fractures frequently have multiple comorbidities making them more susceptible to adverse events from blood loss.19 20 The most common comorbidities of individuals with hip fractures are congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease and diabetes.1 Administering TXA to such patients has a potential to offset blood loss, improve patient outcomes and lower cost of care by decreasing the rate of transfusions.33 34 Five studies, all conducted outside the USA, have previously reported results of using TXA in hip fracture surgery.8–11 35 Sadeghi and Mehr-Aein8 randomised 67 hip fracture patients to receive either placebo injection or intravenous TXA at the time of surgery. They found a significantly lower volume of blood loss (652±228 mL vs 1108±372 mL, p<0.003) and shorter hospital stays (4.3±1.6 days vs 5.8±1.5 days, p<0.05). Vijay et al35 also reported significantly reduced transfusion rates in the TXA arm of their clinical trial. In a retrospective cohort study, Lee et al11 similarly reported a transfusion rate three times lower in patients who received TXA prior to hemiarthroplasty. In a separate randomised controlled trial that compared intravenous administration of TXA to topical TXA administration as well as placebo in hip fracture patients undergoing hemiarthroplasty, both of the TXA groups experienced less blood loss.9

In designing this study, we concluded that hip fracture patients are both likely to experience significant blood loss and are susceptible to the adverse effects of blood loss making them an ideal population to target for a randomised controlled trial of the effects of perioperative TXA on blood loss. We hypothesise that administration of TXA will decrease blood loss in hip fracture patients and lower the rate of allogenic blood transfusion.

Objective

To investigate the hypothesis that TXA will lower blood loss and transfusion rate in patients with hip fractures.

Methods and analysis

Overview of trial design

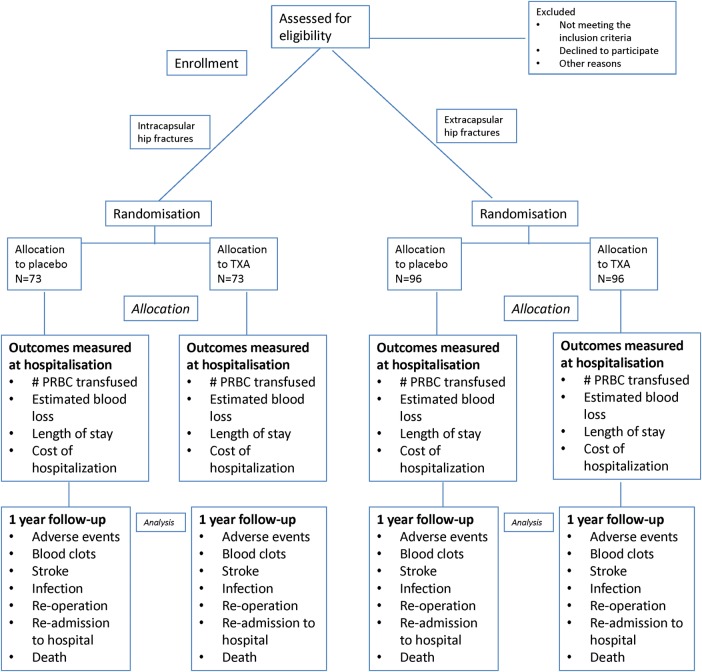

We are conducting a single-centre randomised controlled trial using a parallel two-arm design to investigate whether perioperative TXA use will decrease the rate of transfusion in patients with hip fractures (figure 1). Randomisation will be stratified by type of hip fracture (ie. intertrochanteric vs femoral neck fracture). The surgical team, anesthesia team and patients will be blinded to the assignment. Once consent is obtained and a patient is enrolled, a 1:1 randomisation system will be employed by our institution's investigational pharmacy to assign patients to receive TXA or placebo. Patient enrolment will occur over ∼2 years and enrolled patients will be followed for 1 year postoperatively. Incidence of blood transfusion, total calculated blood loss, and acute adverse events (transfusion reaction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, symptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT), surgical site infection (SSI), and death) will be assessed in the perioperative period. Patients will also be assessed at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months postoperatively to capture long-term adverse events as well as determine mortality rate. This trial is registered (NCT01940536) and has received ethical approval from the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1301013463).

Figure 1.

Study Design (TXA: tranexamic acid; PRBC: packed red blood cells).

Primary research question

In patients with hip fractures, does a single bolus of TXA at the time of surgery result in a lower rate of blood transfusion?

Secondary research question

In patients with hip fractures, does a single bolus of TXA at the time of surgery result in:

Decreased calculated blood loss?

Shorter length of hospitalisation?

Differences in occurrence of adverse events?

Hypothesis

As a primary outcome, there will be a decreased rate of blood transfusion in patients who receive TXA intraoperatively and no significant increase in frequency or severity of adverse events in comparison to patients who receive placebo. This study is powered to address the primary outcome of difference in transfusion rates between the two study arms for intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures.

Setting and participants

Adult patients (over 18 years of age) presenting to a single tertiary care centre with an acute hip fracture will be screened for eligibility. All patients with hip fractures at this institution are admitted to the Medical Orthopaedic Trauma Service (MOTS). Prior to surgery, patients older than 75 years of age, or those with medical comorbidities will be optimised by the general medical service prior to surgery. All potentially eligible patients will be screened and documented as (1) eligible and included, (2) eligible and missed or (3) excluded. The study coordinator will obtain informed consent for participation in the study using the approved IRB Informed Consent forms.

All patients will provide written informed consent and will understand that by entering in the study they may receive either placebo or TXA. Participation in the study is voluntary and their decision to participate will not affect any other aspect of their care in case of refusal. Patients will have the right to withdraw from the study at any point.

Inclusion criteria

Patients admitted through the emergency department or transferred to our institution who meet the following criteria will be included in the study:

Adults over the age of 18

Acute intertrochanteric or femoral neck hip fracture

Patients treated surgically with cephalomedullary nail, hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty (THA)

Exclusion criteria

Patient who meet any one or more of the following criteria will be excluded from the study:

Use of any anticoagulant at the time of admission (eg, vitamin K antagonists, antithrombin agents, antiplatelet agents or factor IIa and Xa inhibitors)

Documented allergy to TXA

History of DVT or pulmonary embolus

Hepatic dysfunction (aspartate transaminase (AST)/alanine transaminase (ALT)>60)

Renal dysfunction (Cr >1.5 of glomerular filtration rate (GFR)>30)

Active coronary artery disease (event in the past 12 months)

History of CVA in the past 12 months

Presence of a drug-eluting stent

Colour blindness

Leukaemia or any active cancer

Coagulopathy based on admission laboratory values (international normalised ratio (INR)>1.4, partial thromboplastin time (PTT)>1.4× normal, platelets <50 000)

Non-displaced femoral neck fractures treated percutaneously

Baseline

Baseline assessment includes sex; birth date; height and weight; mechanism of injury; time from injury to presentation to our institution; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification; Charlson Comorbidity Index; and comorbidities including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, hypertension and history of smoking. The haemoglobin and haematocrit will be recorded at the time of admission and on the morning of surgery.

Blinding

After consent and enrolment in the study, patients will be stratified based on type of hip fracture (intracapsular or extracapsular). Following stratification by fracture type, the institution's investigational pharmacist will perform the randomisation and assign the patient to either receive TXA or placebo. Patients will be randomised in blocks of 20. The packaging of the injections will be performed by the investigational pharmacy and will be identical for TXA and placebo. All patients and clinicians, with the exception of the pharmacist, will remain blinded until the data is analysed.

Intervention

The patients randomised to the treatment arm will receive 1 g of intravenous TXA mixed in 100 cc of saline, bolused at the time of surgical incision. Those assigned to the placebo group will receive an equivalent volume bolus of saline at the time of surgical incision.

Patients with intertrochanteric hip fractures will be treated with a long intramedullary hip screw implant with a trochanteric start point. Patients with displaced femoral neck fractures will be treated with a cemented or non-cemented hemiarthroplasty or THA at the discretion of the treating surgeon. All surgeries will be supervised by the attending surgeon with the assistance of orthopaedic residents. The surgical technique as well as the anaesthetic technique (regional vs general anaesthesia) will be recorded and assessed in the final analysis. The time from injury to surgery will also be recorded and included in the analysis.

Blood transfusion criteria will remain consistent with hospital standards (Hb<8 g/dL or symptomatic anaemia) as determined by an independent, blinded medical team who will follow the patient throughout the hospital stay. Number of blood transfusions received will be documented on patient discharge. Haematocrit and haemoglobin will be recorded daily for all patients while they remain in the hospital. Further monitoring will be conducted based on need as determined by the independent medical team. Estimated blood volume will be calculated using baseline height, weight and gender and the laboaratory values will be used to calculate estimated blood loss postoperatively (see online supplementary appendix 1).36

bmjopen-2015-010676supp_appendix.pdf (27.6KB, pdf)

All patients will be permitted to weight-bear as tolerated postoperatively and DVT prophylaxis will be standardised. All enrolled patients will receive subcutaneous heparin, 5000 units every 8 hours beginning on admission until 12 hours prior to surgery and restarting 6 hours after surgery. Calf mechanical compression devices will also be utilised during the inpatient stay and will remain on at all times with the exception of physical therapy sessions. Following discharge from the hospital patients will be given aspirin 325 mg twice daily for DVT prophylaxis for a total of 6 weeks. Diagnostic studies to assess for thromboembolic events (ie, DVT, pulmonary embolism, and stroke) will be ordered only if the patient develops clinical signs or symptoms that justify their use.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the study will be the rate of blood transfusion from the time of surgery until discharge. Patients will be monitored with serial haemoglobin and haematocrit measurements and their vital signs will be recorded as per the standard of care to determine the need for blood transfusion. Only intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusions will be considered for the primary outcome measure as the drug will be administered at the time of surgical incision. Therefore, we anticipate that TXA administration in this study will only modify the rate of intraoperative or postoperative transfusion, and have no effect on the rate of preoperative transfusion in this population.

Secondary outcome

The secondary study outcomes include the calculated blood loss (calculated based on validated methods as outlined in online supplementary appendix 1), frequency of adverse events (including transfusion reaction, myocardial infarction, symptomatic DVT, pulmonary embolus, CVA, reoperation, readmission, infection and death) (figure 1).

For the study purposes, a transfusion reaction will be defined as any constellation of symptoms during a blood transfusion that necessitate discontinuation of the transfusion.

Myocardial infarction will be defined as a cardiologist diagnosis of myocardial infarction based on a combination of ECG changes, echocardiogram changes, or creatine kinase MB or troponin changes. A pulmonary embolism must be confirmed by pulmonary angiography, CT scan of the chest, echocardiographic visualisation or visualisation of thrombus at autopsy. A symptomatic DVT must be confirmed by venography, CT scan, MRI, or pathological evidence at autopsy. A CVA must be diagnosed by a neurologist and will be defined as an embolic, thrombotic or hemorrhagic vascular accident or stroke with motor, sensory or cognitive dysfunction that persists for longer than 24 hours.37

A SSI will be defined as either superficial or deep infection. Superficial SSI involves only skin or subcutaneous tissue while a deep SSI extends deep to the fascial and muscle layers. Reoperation is defined as any return to the operating room for a procedure related to the fractured hip.

Sample size consideration

Our institutional transfusion rate was calculated based on a random sample of 60 patients and was 65% for extracapsular hip fractures and 35% for intracapsular hip fractures, for an overall transfusion rate of 49%. The average reduction in transfusion rate in the previous five studies using TXA was 20%.8–11 35 We plan to include a total of 338 patients (146 intracapsular hip fractures and 192 extracapsular hip fractures). This study design will achieve 81% power to detect a reduction in blood transfusion from 65% in the placebo control group to 45% in the TXA group with statistical significance set to α equal to 0.05 for the extracapsular hip fracture group. Similarly the study will achieve 81% power to detect a reduction in blood transfusion from 35% in the placebo control group to 15% in the TXA group with statistical significance set to α equal to 0.05 for the intracapsular hip fracture group.

Data analysis plan

Descriptive analyses of the patient population will include reporting means (with SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies (with percentages) for categorical or discrete variables. A χ2 analysis will be conducted to evaluate the superiority of TXA in reducing the rate of transfusion in the TXA group versus the placebo control group. The analysis and reporting of the results of the clinical outcomes will follow the CONSORT guidelines (http://www.consort-statement.org). We will conduct a multiple logistic regression model to determine if type of fracture (intertrochanteric or femoral neck), comorbidities, Charlson comorbidity index, age, time to surgery and mechanism of injury are related to transfusion administration. Similarly we will conduct a multiple linear regression model to determine which variables are related to blood loss. We will also conduct subgroup analyses to determine if the effect of TXA is modified by fracture type (intertrochanteric or femoral neck).

Our a priori hypothesis, based on retrospective data,6 is that patients with intertrochanteric fractures incur more blood loss than femoral neck fractures and will have a higher rate of transfusion. If these subgroup analyses are underpowered, the subgroup data will be used to generate further hypotheses to be tested in the future. All analyses will be performed using Stata 14.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Data safety monitoring

The data safety monitoring board has been established to monitor the trial safety and renew the study biannually. This board is independent of the trial and free of conflicts with any of the investigation team.

Discussion

There is clinical uncertainty and a lack of high-quality evidence regarding the use of TXA in hip fracture patients. Despite its proven efficacy in elective orthopaedic surgery,25 38 the optimal dosing and timing of TXA administration is still debated.39 Furthermore, the efficacy and side effect profile of TXA in patients with fractures remains unclear. The immediate goal of this trial is to provide high-quality evidence that can be used to develop clinical guidelines for use of TXA in patients with hip fractures.

Patients undergoing elective total joint arthroplasty and elective spine surgery represent a different population from patients who sustain hip fractures. A larger percentage of hip fracture patients have significant medical comorbidities, and many have history of cardiac disease.1 While TXA has demonstrated safety and efficacy in patients without significant cardiac disease undergoing elective surgery, there is still debate if TXA will have the same effect in patients with significant comorbidities. 22 25 39 The data investigating TXA in patients with comorbidities is limited, which has further deterred clinicians from using TXA in patients with hip fractures. However, the potential benefit of decreasing blood loss and decreasing the number of transfusions following hip fracture surgery is overwhelming and will likely result in improved patient outcomes, shorter length of stay and lower cost. The study investigators believe that the potential benefit of TXA in such patients outweighs the risk of TXA. The majority of literature regarding TXA has confirmed its safety and squelched concerns that its use will result in higher rates of thrombosis.20 22 30 32 40

Of the five studies investigating the use of TXA in hip fracture patients, four were randomised controlled trials that were underpowered for detecting significant differences in thromboembolic events (table 1).8–11 35 Furthermore, patients were only followed perioperatively, and differences in 6-month and 1-year mortality rates and late-onset complications were not assessed.

Table 1.

Previously reported outcomes of tranexamic acid (TXA) in hip fracture patients

| Use of TXA in patients with hip fractures | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Design | Hip fx (IT or FNF) | TXA regimen | DVT PPX | Sample size | Blood loss (cc) | Transfuse rate % | Thromboembolic events | |

| Lee et al 201511 | UK | Cohort | Hemiarthroplasy only | 1 g bolus preoperative | Tinzaparin | 84 cases/187 controls | – | 6 | 1 |

| – | 19 | 4 | |||||||

| Emara et al 20149 | Egypt | RCT | Hemiarthroplasty only | 10 mg/kg bolus, then 5 mg/kg/hour infusion | Clexane | 20 cases IV/20 cases topical/20 controls | 640* | 5 | 5 |

| 1100* | 32 | 0 | |||||||

| Zufferey et al 201010 | France | RCT | Hip fractures | 15 mg/kg bolus preoperative and 3 h later | Fondaparinux×35 days (mandatory ultrasound) | 57 cases/53 controls | 975 | 42 | 0 |

| 1178 | 60 | 0 | |||||||

| Sadeghi and Mehr-Aein 20068 | Iran | RCT | Hip fractures | 15 mg/kg bolus preoperative | NA | 32 cases/35 controls | 960 | 37 | 0 |

| 1484 | 57 | 0 | |||||||

| Vijay et al 201335 | India | RCT | Hip fractures | 10 mg/kg bolus at surgery | NA | 45 cases/45 controls | 39* | 16 | 0 |

| 91* | 40 | 0 | |||||||

*Drain output. Thromboembolic events include only symptomatic thromboembolic events.

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; FNF, femoral neck fracture; IT, intertrochanteric; NA, not applicable; PPX, prophylaxis; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Four of five studies identified a significant decrease in rate of transfusion in patients who received TXA compared to those that did not.8–11 35 The largest study, with a total of 219 patients, was a cohort study with no randomisation.11 While they found a significant decrease in blood transfusion rate, the study design limits the interpretation of the results secondary to the potential biases of surgeon and patient preference. Several studies excluded all patients with preoperative anemia, which limits the generalisability of their findings.8 9 None of the randomised trials provided a detailed analysis of total number of patients excluded from the study at each stage. While the early results from these studies are promising, the overall validity cannot be confirmed without this information. Similarly, there has yet to be a large study to perform a complete subgroup analysis to determine the efficacy of TXA among intracapsular and extracapsular hip fracture patients. Furthermore, the studies did not follow patients up to 1 year postoperatively, which is our intention. The extended follow-up period allows for assessment of mortality at 12 months as well as incidence of unanticipated adverse events following discharge from the hospital. The most novel characteristic of this study in comparison to the other studies is that it is powered to detect a significant difference in blood transfusion rates in intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures. As the hidden blood loss experienced by hip fracture patients is distinct between these two patterns of hip fractures,6 it is important to demonstrate efficacy in groups independently.

TXA has the potential to decrease transfusion rates by decreasing blood loss in patients with hip fractures. Ultimately, this will decreased hospital length of stay and improve outcomes in the hundreds of thousands of patients with hip fractures every year. If the results prove the efficacy of TXA in hip fracture patients, this study may change the standard of care across the USA for these patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: EBG revised the study from its original form and condensed the application of the tranexamic acid to one dose in the operating room in order to facilitate the flow of the project. This author made substantial contributions to the planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. MRG conceived of the study and designed the first draft of the protocol. He was awarded the Thomas P. Sculco Research Grant and the Joseph M. Lane Research Grant for his proposal of the project. He made substantial contributions to the drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. AL made substantial contributions to the study design, modifications of the study to conform to guidelines and for logistics. She will also be involved in patient recruitment, data collection and analysis. This author made substantial contributions to the design of the work, planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. SJW made substantial contributions to the design of the work, planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. AN facilitated IRB submissions and amendments. He is also coordinating the enrolment of patients in the study and working with the orthopaedic trauma team during the process of drug administration. This author made substantial contributions to the design of the work, planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. TT is the main anaesthesiologist who will be orchestrating the anaesthesiologists who administer the drug prior to skin incision. This author made substantial contributions to the design of the work, planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. EF is the head of the Medical Orthopaedic Trauma Service (MOTS) who organises the medical attendings who manage the patients following surgery. This author made substantial contributions to the design of the work, planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work. DGL is the chief of the orthopaedic trauma service at NYP. This author made substantial contributions to the design of the work, planning of data analysis, drafting and revising of the protocol, final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of the work.

Funding: This work is supported by a Dr. Thomas Sculco grant and a Dr. Joseph M. Lane grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The study has not begun enrolment yet, so there is no data to share at this time. Updates will be available on the clinicaltrials.gov website.

References

- 1.Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM et al. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA 2009;302:1573–9. 10.1001/jama.2009.1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richmond J, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD et al. Mortality risk after hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2003;17:53–6. 10.1097/00005131-200301000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyes GJ, Tucker A, Marley D et al. Predictors for 1-year mortality following hip fracture: a retrospective review of 465 consecutive patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2015. [Epub ahead of print Aug 2015]. 10.1007/s00068-015-0556-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah MR, Aharonoff GB, Wolinsky P et al. Outcome after hip fracture in individuals ninety years of age and older. J Orthop Trauma 2001;15:34–9. 10.1097/00005131-200101000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sathiyakumar V, Greenberg SE, Molina CS et al. Hip fractures are risky business: an analysis of the NSQIP data. Injury 2015;46:703–8. 10.1016/j.injury.2014.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foss NB, Kehlet H. Hidden blood loss after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:1053–9. 10.1302/0301-620X.88B8.17534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith GH, Tsang J, Molyneux SG et al. The hidden blood loss after hip fracture. Injury 2011;42:133–5. 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadeghi M, Mehr-Aein A. Does a single bolus dose of tranexamic acid reduce blood loss and transfusion requirements during hip fracture surgery? A prospective randomized double blind study in 67 patients. Acta Medica Iranica 2007;45:437–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emara WM, Moez KK, Elkhouly AH. Topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid as a blood conservation intervention for reduction of post-operative bleeding in hemiarthroplasty. Anesth Essays Res 2014;8:48–53. 10.4103/0259-1162.128908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zufferey PJ, Miquet M, Quenet S et al. Tranexamic acid in hip fracture surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2010;104:23–30. 10.1093/bja/aep314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee C, Freeman R, Edmondson M et al. The efficacy of tranexamic acid in hip hemiarthroplasty surgery: an observational cohort study. Injury 2015;46:1978–82. 10.1016/j.injury.2015.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill GE, Frawley WH, Griffith KE et al. Allogeneic blood transfusion increases the risk of postoperative bacterial infection: a meta-analysis. J Trauma 2003;54:908–14. 10.1097/01.TA.0000022460.21283.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shokoohi A, Stanworth S, Mistry D et al. The risks of red cell transfusion for hip fracture surgery in the elderly. Vox Sang 2012;103:223–30. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2012.01606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saleh A, Small T, Chandran Pillai AL et al. Allogenic blood transfusion following total hip arthroplasty: results from the nationwide inpatient sample, 2000 to 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:e155 10.2106/JBJS.M.00825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kagoma YK, Crowther MA, Douketis J et al. Use of antifibrinolytic therapy to reduce transfusion in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery: a systematic review of randomized trials. Thromb Res 2009;123:687–96. 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eubanks JD. Antifibrinolytics in major orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2010;18:132–8. 10.5435/00124635-201003000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan C, Zhang H, He S. Efficacy and safety of using antifibrinolytic agents in spine surgery: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e82063 10.1371/journal.pone.0082063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zufferey P, Merquiol F, Laporte S et al. Do antifibrinolytics reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in orthopedic surgery? Anesthesiology 2006;105:1034–46. 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tse EY, Cheung WY, Ng KF et al. Reducing perioperative blood loss and allogeneic blood transfusion in patients undergoing major spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:1268–77. 10.2106/JBJS.J.01293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R et al. , CRASH-2 trial collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A et al. , CRASH-2 collaborators. The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: An exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:1096–101, 1101.e1–2 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60278-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whiting DR, Gillette BP, Duncan C et al. Preliminary results suggest tranexamic acid is safe and effective in arthroplasty patients with severe comorbidities. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:66–72. 10.1007/s11999-013-3134-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cid J, Lozano M. Tranexamic acid reduces allogeneic red cell transfusions in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion 2005;45:1302–7. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemay E, Guay J, Cote C et al. Tranexamic acid reduces the need for allogenic red blood cell transfusions in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Can J Anaesth 2004;51:31–7. 10.1007/BF03018543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ 2014;349:g4829 10.1136/bmj.g4829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raksakietisak M, Sathitkarnmanee B, Srisaen P et al. Two doses of tranexamic acid reduce blood transfusion in complex spine surgery: a prospective randomized study. Spine 2015;40:E1257–63. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wind TC, Barfield WR, Moskal JT. The effect of tranexamic acid on transfusion rate in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:387–9. 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuttle JR, Ritterman SA, Cassidy DB et al. Cost benefit analysis of topical tranexamic acid in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1512–15. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang F, Wu D, Ma G et al. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss and transfusion in major orthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis. J Surg Res 2014;186:318–27. 10.1016/j.jss.2013.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishihara S, Hamada M. Does tranexamic acid alter the risk of thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty in the absence of routine chemical thromboprophylaxis? Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:458–62. 10.1302/0301-620X.97B4.34656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duncan CM, Gillette BP, Jacob AK et al. Venous thromboembolism and mortality associated with tranexamic acid use during total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:272–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang ZG, Chen WP, Wu LD. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:1153–9. 10.2106/JBJS.K.00873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foss NB, Kristensen MT, Kehlet H. Anaemia impedes functional mobility after hip fracture surgery. Age Ageing 2008;37:173–8. 10.1093/ageing/afm161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence VA, Silverstein JH, Cornell JE et al. Higher hb level is associated with better early functional recovery after hip fracture repair. Transfusion 2003;43:1717–22. 10.1046/j.0041-1132.2003.00581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vijay BS, Bedi V, Mitra S et al. Role of tranexamic acid in reducing postoperative blood loss and transfusion requirement in patients undergoing hip and femoral surgeries. Saudi J Anaesth 2013;7:29–32. 10.4103/1658-354X.109803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015;25:129–33. 10.1007/s00590-014-1457-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basques BA, Toy JO, Bohl DD et al. General compared with spinal anesthesia for total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:455–61. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danninger T, Memtsoudis SG. Tranexamic acid and orthopedic surgery-the search for the holy grail of blood conservation. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:77–5839. 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.01.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simmons J, Sikorski RA, Pittet JF. Tranexamic acid: from trauma to routine perioperative use. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2015;28:191–200. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillette BP, DeSimone LJ, Trousdale RT et al. Low risk of thromboembolic complications with tranexamic acid after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:150–4. 10.1007/s11999-012-2488-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010676supp_appendix.pdf (27.6KB, pdf)