Abstract

Objectives

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) provide important information about the impact of treatment from the patients' perspective. However, missing PRO data may compromise the interpretability and value of the findings. We aimed to report: (1) a non-technical summary of problems caused by missing PRO data; and (2) a systematic review by collating strategies to: (A) minimise rates of missing PRO data, and (B) facilitate transparent interpretation and reporting of missing PRO data in clinical research. Our systematic review does not address statistical handling of missing PRO data.

Data sources

MEDLINE and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases (inception to 31 March 2015), and citing articles and reference lists from relevant sources.

Eligibility criteria

English articles providing recommendations for reducing missing PRO data rates, or strategies to facilitate transparent interpretation and reporting of missing PRO data were included.

Methods

2 reviewers independently screened articles against eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved with the research team. Recommendations were extracted and coded according to framework synthesis.

Results

117 sources (55% discussion papers, 26% original research) met the eligibility criteria. Design and methodological strategies for reducing rates of missing PRO data included: incorporating PRO-specific information into the protocol; carefully designing PRO assessment schedules and defining termination rules; minimising patient burden; appointing a PRO coordinator; PRO-specific training for staff; ensuring PRO studies are adequately resourced; and continuous quality assurance. Strategies for transparent interpretation and reporting of missing PRO data include utilising auxiliary data to inform analysis; transparently reporting baseline PRO scores, rates and reasons for missing data; and methods for handling missing PRO data.

Conclusions

The instance of missing PRO data and its potential to bias clinical research can be minimised by implementing thoughtful design, rigorous methodology and transparent reporting strategies. All members of the research team have a responsibility in implementing such strategies.

Keywords: patient-reported outcomes, health-related quality of life, missing data, quality assurance, systematic review, methodology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review collates practical strategies to minimise the problem of missing patient-reported outcome (PRO) data. Recommendations were retrieved from 117 multidisciplinary sources and potential drawbacks of each recommendation are presented.

Missing PRO data may be preventable in many cases by implementing rigorous study design and methodological strategies, as described in this review.

In some clinical research settings, missing PRO data is not avoidable due to deteriorating health status of the participants. Strategies to minimise the potential for bias caused by missing PRO data are described.

This paper discusses one aspect of PRO data quality: data completeness. Many other factors also contribute to high-quality PRO data, including but not limited to appropriateness of PRO measures, timing of PRO assessment, ensuring patients self-complete and clinical versus statistical significance of findings.

This review excludes non-English sources. The non-English publications may have been relevant; however, given the repetition of themes found in our 117 included sources we do not believe that these would significantly affect our findings.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and specific symptoms, provide unique information about the effect of disease and treatment on the patient. PRO research evidence is crucial for informed clinical and policy decision-making, and is increasingly being used to inform labelling claims for medical products.1–3 The quality and value of PRO evidence is contingent on a number of factors, including: provision of a clear rationale for PRO assessment, the choice of PRO measure, the timing of PRO assessments, and ensuring the responses are the patient's own. One critical PRO quality assurance issue is missing data, defined as “…values that are not available and that would be meaningful for analysis if they were observed” (ref. 4, p. 1355). Conversely, researchers may measure ‘PRO assessment compliance’, which refers to the number of completed questionnaires received as a proportion of the number expected, given the study design, and the number of patients still alive and enrolled in the study.5 6 Both definitions acknowledge that questionnaires are not expected from patients who have died.4–6

The practical and methodological issues associated with missing PRO data received considerable attention in the literature in the 1990s. An expert workshop on the prevention and analysis of missing PRO data in trials led by international cancer trials groups was held in 1996, with findings published in a dedicated special issue of Statistics in Medicine.7 Yet problems with missing PRO data persist; high rates of missing PRO data continue to be reported in clinical trials,8–10 and PRO compliance rates are sometimes so poor that PRO data are not analysed.11

Persisting PRO compliance problems may reflect the sporadic attention the issue has received in the literature over the past 20 years,4 most of which is targeted to statisticians handling missing PRO data during analysis. This is problematic for four reasons: first, content targeted at statisticians may be conceptually and technically inaccessible to non-specialists; second, content addressing statistical handling of missing data does not acknowledge that some missing PRO data is preventable through study design and implementation; third, it promotes an attitude that the problem of missing data is the sole responsibility of the statistician; and fourth, appropriate statistical handling of missing PRO data is often contingent on other research data, and this will require consideration at the trial design stage. The broader research team should understand the issues associated with missing data, and their role in minimising related problems. This team includes individuals involved in study design and planning; recruitment; data collection; quality assurance; and analysing, interpreting or reporting of the results. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a systematic review targeting the role of the broader research team in maximising PRO compliance rates, and minimising the problem of missing PRO data.

This paper has two aims, and is accordingly structured in two parts:

To summarise the problems created by missing PRO data in a format accessible to anyone involved in designing, conducting or analysing clinical research.

- To systematically review the multidisciplinary literature to identify and collate strategies relevant to the entire research team to:

- Maximise PRO compliance rates through study design and implementation;

- Reduce the potential for biased interpretation caused by missing PRO data through PRO-specific strategies for research design, implementation and reporting.

Part 1: the problem of missing PRO data—a summary of the issues

Missing PRO data create challenges for data analysis, and can compromise the interpretability and value of PRO findings for three major reasons: first, missed observations reduce study power.12 Studies with secondary PRO end points are usually sufficiently powered for PRO analyses when the sample size calculation is based on a survival primary end point (eg, progression-free survival) because these typically require larger sample sizes. However, a high proportion of missing PRO data will substantially reduce power and inflate standard error.13 This increases the risk of type 2 errors, that is, false-negative findings.

Second, and more problematically, missing data may be related to the measured outcome (ie, HRQOL, pain, etc).12 For example, non-completers who dropped out of Southwest Oncology Group trials due to death had worse HRQOL at baseline, and at time of drop out than other participants.5 In many cases, this type of missing PRO data is unavoidable, yet it cannot be ignored as doing so may lead to biased estimates—the extent of which is impossible to calculate.13

Third, the presence of missing data undermines randomisation, and makes intention-to-treat analyses (analysing according to randomised groups) less valid as missing data create a need to make assumptions about the data that are not always verifiable.14

Difficulties in statistically handling missing PRO data

There are many options for statistically handling missing PRO data. Each method makes assumptions about the missing data mechanism,15 which is a fairly technical system for classifying missing data according to their probable cause (see box 1). The challenge is to handle missing data in a way that closest resembles the true, albeit unverifiable, missing data mechanism, since the mechanism often has a greater impact on research results than does the proportion of missing data.16 To use a simple example—if PRO data are truly missing not at random (MNAR; eg, missing due to declining health), but the analysis method used assumes missing data are missing completely at random (eg, missing due to institution error) by excluding cases with missing data, then the analysed data represents only the better-performing patients. Therefore, in addition to some loss of study power, the findings may falsely indicate that PROs are more favourable than is the true case, thus potentially leading to biased interpretation of change over time within groups, or of between-group differences.13 If the missing data appear MNAR, and are handled and interpreted sensibly (within the specific clinical and study context), the risk of introducing bias is reduced. Although statistical approaches are available, it is critical to prevent missing data, where possible, rather than to rely solely on statistical approaches. Prevention, statistical handling, interpretation and transparent reporting of missing PRO data are complementary strategies. It is recommended that statistical handling of missing PRO data be undertaken by a statistician as the methods used are technical. Therefore, statistical handling of missing PRO data is not addressed in our systematic review below. Interested readers are referred to Bell and Fairclough17 for detailed discussion.

Box 1. The missing data mechanism.

▸ Missing completely at random (MCAR)

The probability of missing data is unrelated to past, current and future patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores/health status such as administrative errors.18 MCAR assumes the participants with missing data are a random sample of the whole sample.18 Therefore, assuming the study is adequately powered, the results should not be altered too much if the MCAR are ignored in analysis; however, the standard error of the estimates will be inflated.19 Many examples of MCAR are caused by poor study design and implementation, and are hence ‘preventable’ sources of missing PRO data.

▸ Missing at random (MAR)

The probability of missing data depends on observed data or a fixed covariate, but not on the current (missing) or future PRO scores; for example, if a particular cultural group has a high proportion of missing data and patients from this group tend to have poorer PRO scores.13 Depending on whether the variable contributing to the likelihood of missing data is ‘informative’ (related to measured health outcome) or ‘ignorable’ (unrelated), using a statistical method that ignores MAR may distort the findings, potentially introducing bias.19 MAR is difficult to ascertain, but methods are available to test for (albeit with some uncertainty12 20) and analyse MAR PRO data.12 21

▸ Missing not at random (MNAR)

The probability of missing data depends on current and future unobserved scores. PRO scores previously observed are constant but would decline at (or after) drop out, and the process of decline is not observed.18 Data that meet the MNAR assumption are always ‘informative’, that is, missing due to the patient's declining health status, but the extent of decline is not known because it is not observed. Few methods are available for unbiased analysis of MNAR.21

Part 2: a systematic review of strategies to maximise PRO compliance rates and reduce the potential for bias

Part 1 of this paper summarised the problem of missing PRO data for the analysis and interpretation of study results. This motivates part 2 of our paper: a systematic review of strategies for all research team members to assist in minimising the problem of missing PRO data.

Systematic review methods

Search strategy

MEDLINE and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases were systematically searched using a search strategy (see online supplementary appendix A) which combined PRO terms with missing data and compliance terms. These databases were chosen as they canvassed the disciplines of interest to our review, and because they indexed key papers already known to the authors. The search strategy was developed by first reviewing literature to identify key search terms. We sought advice from three librarians with expertise in systematic reviews to ensure all relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were addressed, and conducted several pilot searches to capture targeted papers. The MEDLINE search was restricted to English language articles. Reference lists and citations of included papers retrieved in the database search were screened (by title) for additional relevant sources, using the same eligibility criteria.

bmjopen-2015-010938supp_appendices.pdf (228.6KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Papers were included if they provided guidance or recommendations for minimising/preventing missing PRO data in prospective research designs, or for transparent interpretation and reporting of missing PRO data to minimise risk of potential interpretation bias. We excluded non-English articles; conference presentations; research protocols; papers discussing statistical handling of missing PRO data, instrument development, proxy-reporting, patient-reported behaviours (smoking, drug use, etc), non-patient samples and papers reporting general study/trial drop-out rates.

Study selection

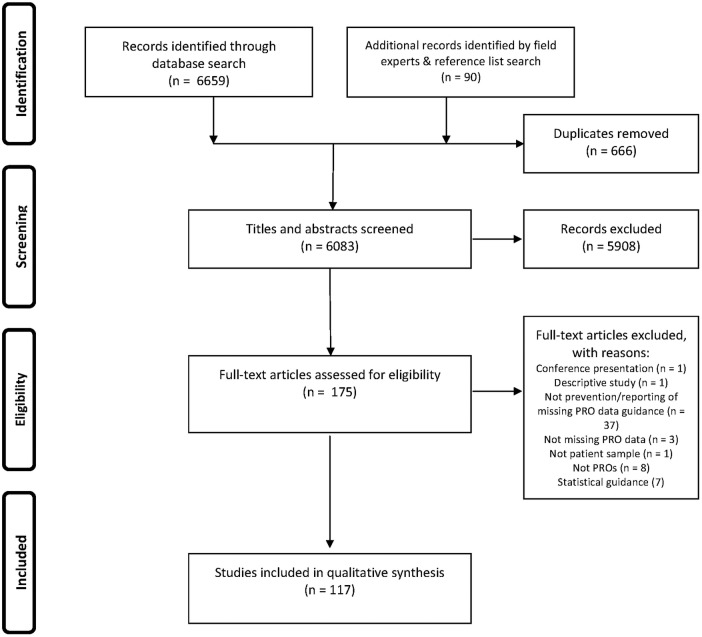

Two reviewers (RM-B and MJP) independently screened article titles and abstracts using the eligibility criteria. Screening discrepancies were discussed and settled with two senior authors (MB and MTK). Abstracts that appeared to meet the criteria were obtained in full text and assessed against the same criteria. Our search and study selection process complied with Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines22 (see online supplementary appendix B).

Extraction and coding of recommendations

Recommendations were extracted, coded and analysed using framework synthesis methodology (RM-B).23 24 An a priori framework was used to organise recommendations into three categories (study design and planning, during active study, reporting), then coded according to the specific recommendation (eg, minimise patient burden). These codes were refined and developed during the process, and organised into three code levels on completion. For example, the major category of ‘minimise patient burden’ was subcategorised into ‘assistance to patients’, ‘questionnaire content’, ‘length of assessments’ and ‘validated questionnaires’. Each subcategory was further categorised for specificity; for example, the third-level categories for ‘length of assessments’ includes ‘fewer assessments’, ‘shorter questionnaire’, ‘use screening questions’, etc. Three reviewers (MTK, MJP, MB) each checked 10% of extractions. Frequencies of each unique recommendation were calculated, and potential drawbacks of each recommendation were described. Two reviewers (MJP, MTK) checked 100% of the final results tables. Disagreements were discussed as a team to achieve consensus.

Results

One hundred and seventeen articles (listed in online supplementary appendix C) met the inclusion criteria (figure 1). These arose from oncology, palliative care and other disease-specific and non-disease-specific PRO literature (table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRO, patient-reported outcome.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included sources

| N | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 117 | 100.0 |

| Disease | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 | 2.6 |

| Non-specific | 22 | 18.8 |

| Oncology | 65 | 55.6 |

| Orthopaedics | 3 | 2.6 |

| Pain | 2 | 1.7 |

| Palliative care | 6 | 5.1 |

| Women's health | 3 | 2.6 |

| Other | 13 | 11.1 |

| Publication type | ||

| Discussion/review | 64 | 54.7 |

| Guideline | 3 | 2.6 |

| Meta-analysis | 2 | 1.7 |

| Original research | 30 | 25.6 |

| Systematic review | 9 | 7.7 |

| Text book | 6 | 5.1 |

| Other | 3 | 2.6 |

| Year of publication (range) | ||

| 1988–1989 | 3 | 2.6 |

| 1990–1999 | 40 | 34.2 |

| 2000–2009 | 47 | 40.2 |

| 2010–2015 | 27 | 23.1 |

Design strategies to minimise the problem of missing PRO data

Recommendations for reducing the problem of missing PRO data through study design are summarised in 12 categories in table 2: PRO assessment schedule: a clinically informative and feasible assessment schedule should be defined, with acceptable assessment time windows and stopping rules; collection of auxiliary or supporting data: collect information to facilitate unbiased interpretation of PRO data in the presence of missing data, such as clinician-rated health status, observational or proxy-reported data; eligibility criteria: include literacy and language requirements, and the need for a valid baseline PRO assessment; feasibility issues: considerations for determining required resources and ensuring the PRO study is feasible; guidance: for trial team members to standardise administration and maximise PRO completion rates; mode of questionnaire administration (MOA): MOA should be feasible and acceptable, and impact on PRO completion rates should be considered; minimise participant burden: employ strategies to ensure PRO assessment is easy and acceptable to participants; PRO measure: PRO measures should be clinically relevant, validated, and acceptable to patients; PROs part of the trial: incorporate PROs into all relevant study documents and ensure the team is committed to the PRO study; quality assurance: prepare databases, study guidance and procedures with ongoing quality assurance in mind; sample: ensure the PRO sample size is representative and sufficient for planned analyses; team involved in design/protocol development: involve a multidisciplinary team, including PRO experts, clinicians, nurses, site coordinators, patients and others.

Table 2.

Study design and planning strategies to minimise the problem of missing PRO data

|

Category |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Topic | Specific recommendation | N recommendations* | Potential drawbacks | Source/s: first author (year). Full citations are provided as Online Supplementary Appendix C |

| Assessment schedule | Specify PRO assessment time points | Specify the required PRO assessment time points | 2 | None | Bernhard, Gusset (1998), Beitz (1996) |

| Specify the minimum PRO data requirements (eg, ‘baseline, on and off treatment, and and/or end of study’ (ref. 5, p. 524) | 3 | May create impression that additional PRO assessments are not important | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | ||

| PRO assessment schedule if treatment schedule is disrupted (ie, will the PRO assessment schedule be altered if the treatment schedule is altered?) | 1 | None | Fairclough (2010) | ||

| Time point selection (guidance on how to select PRO assessment time points) | Align PRO assessments to clinic visits so that data may be captured while the patient visits the clinic | 16 | Clinic visits may not be most informative to capture particular treatment effects (eg, chemotherapy toxicity) | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Moinpour (1998), Movsas (2003), Aaronson (1990), Land (2007), Walker (2003), Calvert (2004), Sprague (2003), Revicki (2005), Fairclough (2010), Kyte (2013), Blazeby (2003), Simes (1998) | |

| May be burdensome to participants to attend clinic for regular assessments | |||||

| Align assessment schedule to a fixed reference point (for ease of calculating when PRO assessments are due) | 1 | May be burdensome to participants to attend regular assessments | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | ||

| Allow sufficient breaks between PRO assessments | 1 | May not be feasible if investigators wish to capture acute disease/treatment effects or their frequency via PROs | Sherman (2005) | ||

| Assess PROs of palliative care patients weekly | 4 | Does not consider when PRO assessment would be most meaningful | Tang (2002) | ||

| Balance the number of required PRO assessments (not too few, not too many) | 4 | None | Revicki (2005), Fairclough (2010) | ||

| Consider patient treatment and expected survival when planning assessment schedule (added note: avoid PRO assessments beyond the point of expected median survival) | 3 | None | Kaasa (2002), Hahn (1998), Atherton (2006) | ||

| Select clinically meaningful time points (ie, ensure that PRO assessments will be taken at clinically informative times, ie, to capture the trajectory of treatment and recovery) | 4 | Clinically meaningful PRO assessment time points may not align with clinic visits, which may require alternative modes of administration | Ganz (2007), Jordhoy (1999), Tang (2002) | ||

| Event-driven PRO assessment for a subsample (ie, rather than subjecting entire sample to detailed PRO assessments if they experience certain clinical events, it may minimise staff effort and resources to restrict these additional assessments to a subsample only) | 2 | Event-driven PRO assessment can be logistically challenging to implement | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Simes (1998) | ||

| Focus on short-term outcomes in patients with advanced disease (focusing on long-term outcomes in such samples will lead to high rates of missing PRO data, and uninformative data) | 1 | May not be clinically meaningful to assess short-term outcomes in all studies | Ganz (2007) | ||

| Justify chosen PRO assessment time points | 1 | None | Ganz (2007) | ||

| Minimise PRO assessment time points (select fewer time points to minimise burden and resource usage) | 3 | May sacrifice important information by omitting time points, for example, differences between treatment arms5 | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Macefield (2013), Cella (1995) | ||

| Shorter follow-up duration (avoid following up patients for a longer period of time as participants are more likely to drop out over time) | 1 | May sacrifice important information by ceasing PRO assessment too early in some studies. Some studies may be interested in long-term follow-up/survival outcomes. | Little, Cohen (2012) | ||

| Treatment failure/cessation | Continue PRO assessments after treatment failure | 6 | May be difficult to engage or contact participants beyond point of treatment failure | Hao (2010), Little, D'Agnostino (2012), Sprangers (2002), Chassany (2002), Cella (1995), Cella (1994) | |

| Specify procedures for contacting participants after treatment cessation | 3 | None | Cella (1994), Revicki, Hao (2010) | ||

| Specify the PRO assessment stopping rule (ie, under what circumstances should PRO assessments discontinue) | 3 | None | Bell (2014), Kaasa (1992), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Time windows | Define PRO assessment time windows (ie, baseline assessment time window should always end before the intervention/treatment commences. Follow-up assessment time windows should border the period in which treatment effects of interest are anticipated, for example, if the time point is 1 week postsurgery, a valid assessment may occur anytime between 4 and 12 days postsurgery). | 12 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Cella (1994), Wisniewski (2006), Blazeby (2003), Hopwood (1996), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Fayers (1997), Hopwood (1998), Revicki (2005), Fairclough (2010), Cella (1995) | |

| Flexible/large time windows (very narrow time windows may be logistically infeasible to implement and so risk of missing PRO data may be reduced by setting larger time windows) | 3 | Not all time windows can be flexible, particularly when assessing acute effects of treatment | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Little, Cohen (2012), McMillan (2003) | ||

| Collect additional/supporting data (which can be used during PRO data analysis and interpretation) | Auxiliary data (to assist interpretation if there are some missing PRO data). Suggestions of types of auxiliary data in the next column | Additional information about non-responders (type of additional information unspecified) | 1 | Requires prespecification, and additional time and resources to collect | Kim (2004) |

| Clinical data | 1 | Requires additional time and resources to collect | Newgard (2010) | ||

| Health status (clinician-rated quality of life index, Karnofsky or ECOG performance status) | 6 | Requires additional clinician time | Coates (1998), Bell (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Simes (1998), Revicki (2005), Fairclough (2010) | ||

| Comorbidity data | 1 | Requires additional time and resources to collect | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | ||

| Concomitant medications | 1 | Requires additional time and resources to collect | Beitz (1996) | ||

| Observation data | 1 | Requires additional time and resources to collect | Kaasa (2002) | ||

| Participant clinical data | 1 | None | Newgard (2010) | ||

| Participant demographics | 2 | None | Altman (2007), Newgard (2010) | ||

| Proxy† reports when participant is no longer able to self-complete | 21 | Proxy reports are not always concordant with participant self-reports. Care must be taken when interpreting proxy data. This is a specialist subject and additional reading is recommended for investigators considering to use proxy assessment.64 | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Chassany (2002), Fayers (1997), Jordhoy (2010), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Kyte (2013), Machin (1998), Moynihan (1998), Peruselli (1997), Revicki (2005), Rock (2007), Simes (1998), Sprangers (2002), Stewart (1992), Taphoorn (2010), Walker (2003) | ||

| Toxicity data | 2 | Requires additional time and resources to collect, if not already being collected as part of the study | Fairclough (2010), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Unspecified (use an alternative to PRO in final weeks of life) | 1 | Requires additional time and resources to collect. Additional drawbacks may be apparent depending on specific alternative measure/s used. | Jordhoy (2010) | ||

| Collect reasons for missing PRO data | – | – | See ‘cover sheet’ section in administration procedures in table 3 | ||

| Eligibility criteria for PRO study (suggestions of specific eligibility or inclusion criteria) | Consider the participants' ability to complete PROs | Include—‘participant must be able to complete PROs’ as an inclusion criterion | 2 | Ability to complete PRO assessments may change over the course of treatment. Results may not be generalisable to all patients. | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Huntington (2005) |

| Exclude patients with language/cognitive barriers from the PRO study only (ie, these participants are able to take part in other aspects of the trial, but will not be included in the PRO study) | 2 | May reduce the sample size/power of PRO study. Results may not be generalisable to all patients. | Hopwood (1998), Sprague (2003) | ||

| Baseline PRO completion (some sources recommended include baseline PRO completion as an eligibility criterion) | 29 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Calvert (2004), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Chassany (2002), Conroy (2003), Fayers (1997), Hayden (1993), Hopwood (1998), Hurny (1992), Kaasa (1998), Movsas (2003), Osoba (1992), Osoba (2007), Sadura (1992), Simes (1998), Sprangers (2002), Walker (2003), Young, Maher (1999), Young de Haes (1999) | ||

| Include patients with minimal level of impairment (as per baseline PRO) to ensure inclusion of patients with severe disease | 1 | May lead to selection bias | Chassany (2002) | ||

| May impact generalisability of results | |||||

| Surviving long enough to complete PROs (palliative care) | 3 | Difficult to estimate in some cases, so prognostic cues predictive of death may be more practical; may introduce selection bias. | Bakitas (2009), Jordhoy (1999), Chassany (2002) | ||

| Participants’ willingness to complete PROs | 3 | May result in selection bias; patients more willing to take part in PRO study may differ systematically from non-participants. | Fayers (1997), Sprague (2003) | ||

| Feasibility issues of PRO studies | Pilot study | Determine feasibility of PRO study (potential issues, resources required and/or sample size), and acceptability by conducting a pilot study | 9 | Requires time and resources | Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Groenvold (1999), Hurny (1992), Moinpour (1989), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Young, de Haes (1999), Sherman (2005), Wisniewski (2006) |

| Determine compliance targets by conducting a pilot study | 1 | Requires a long pilot study to determine; significant time and resources | Hahn (1998) | ||

| Conduct a pilot study to determine average time to complete PRO measures | 1 | Requires time and resources | Kleinpell-Nowell (2000) | ||

| Use the PRO pilot study as a training opportunity for less experienced staff | 1 | Requires time and resources | Cella (1995) | ||

| PRO resources | Ensure there is sufficient funding for the PRO study and that the PRO study is included in study budget | 5 | Funding can be difficult to obtain; however, it is possible to minimise costs of PRO studies at no cost to high-quality PRO research | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Cella (1995), Coates (1998), Gotay (2005), Moynihan (1998) | |

| Resource allocation—ensure recruiting sites are sufficiently resourced for the PRO study | 15 | Funding can be difficult to obtain across all sites especially if recruiting internationally or trans-nationally. | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Hayden (1993), Hopwood (1998), Hopwood (1996), Kaasa (1992), Moinpour (1998), Moynihan (1998), Revicki (2005), Scott (2004), Sprague (2003), Walker (2003), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Ensure adequate staff at potential sites | 2 | Funding to employ new staff can be difficult to obtain | Revicki (2005), Scott (2004) | ||

| Minimise resources required for the PRO study | 4 | Care must be taken not to sacrifice quality of data or performance | Bernhard, Cella (1998), McMillan (2003) | ||

| Selection of recruiting sites | Select sites with good compliance record | 1 | May limit the number of participants recruited; may overly burden particular sites; potential for selection bias65 | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | |

| Select sites with adequate resources | 2 | May limit the number of participants recruited | Hurny (1992) | ||

| Sites with adequate resources may not necessarily be sites with best compliance record. | |||||

| Provide PRO-specific guidance for the research team | PRO administration guidance (for site staff) | General administration guidance aiming to standardise administration of PROs | 27 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Calvert (2004), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Fayers (1997), Friedman (1998), Ganz (1988), Hahn (1998), Hayden (1993), Hopwood (1998), Kaasa (1998), Kaasa (1992), Land (2007), Newgard (2010), Osoba (1996), Osoba (1992), Sprangers (2002), Taphoorn (2010), Vantongelen (1989), Walker (2003), Wisniewski (2006) |

| Flexible processes across sites (There may be local variations in who is responsible for PRO data collection at different sites; therefore, procedures should be flexible to accommodate such differences.) | 1 | May introduce bias if procedures differ too much between recruiting sites | Bernhard, Peterson (1998) | ||

| Importance of complete data must be stressed in PRO administration guidance | 1 | None | Fayers (1997) | ||

| Instructions to give to participants must be specified in PRO administration guidance | 1 | None | Wisniewski (2006) | ||

| Procedures for missed assessments must be specified in PRO administration guidance | 1 | None | Calvert (2004) | ||

| Staff roles must be specified in PRO administration guidance | 3 | None | Poy (1993), Young de Haes (1999) | ||

| Procedures for handling special situations must be specified in PRO administration guidance | 5 | Not all difficult situations can be predicted in advance | Hahn (1998), Hopwood (1998), Hopwood (1996), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Protocol guidance60 61 63 | Follow PRO protocol guidance (investigators) | 2 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Osoba (2007) | |

| Develop protocol guidance for investigators (trials groups) | 1 | None | Osoba (1996) | ||

| MOA (ie, is the questionnaire administered in hardcopy (pen and paper), electronically, over the phone, etc) | Choice of MOA | Consider costs involved with each MOA | 1 | None | Macefield (2013) |

| Consider impact of MOA on participants’ willingness to disclose information | 1 | The most acceptable MOA for participants may not be the most cost-effective or feasible | Hallum-Montes (2014) | ||

| Consider potential impact MOA on response rate | 3 | None | Hallum-Montes (2014), Cantrell (2007) | ||

| Consider inclusion of remote participants (web-based modes may be more accommodating to remote patients than face-to-face administration) | 1 | None | Cantrell (2007) | ||

| Mode preferred by sample | 1 | Requires additional pilot work to gauge participant preferences. Requires additional staff time and costs. Need to ensure equivalence of modes66 | Basch (2012) | ||

| Electronic modes of administration ‘e-PROs’, for example, using a computer, tablet, smart phone, etc | Allow participants to complete on their preferred electronic device | 1 | Requires resources to ensure compatibility of database across many types of electronic devices | Jansen (2013) | |

| Allows real-time compliance monitoring | 1 | None | Basch (2012) | ||

| Avoid fancy layouts | 1 | None | Cantrell (2007) | ||

| Avoid mandating completion of all items | 2 | May lead to missing item-level data if questions are of sensitive nature67 | Cantrell (2007), Hanscom (2002) | ||

| Present items one at a time | 1 | May be burdensome for participants considering cumulative time required to click between screens | Hanscom (2002) | ||

| Avoid question presentation one at a time (to reduce response burden) | 2 | None | Cantrell (2007), Hallum-Montes (2014) | ||

| Dialogue boxes for missed items | 1 | May be costly to develop | Wisniewski (2006) | ||

| Electronic dictation of questions | 1 | May be costly to develop | Hallum-Montes (2014) | ||

| Email PRO assessment reminders to participants | 1 | Requires time/resources to implement | Cantrell (2007) | ||

| e-PROs encouraged | 1 | e-PRO assessment may not be acceptable to some patient populations. | Basch (2012) | ||

| May be subject to technical fault/data protection/connectivity issues | |||||

| Keep assessment simple to reduce risk of technical fault | 1 | None | Hjermstad (2012) | ||

| Make all items mandatory | 1 | May lead to incomplete questionnaires if questions are of a sensitive nature | Cantrell (2007) | ||

| Flexible MOA | Follow-up missed assessments with alternate mode (eg, if participant misses a face-to-face visit in which hardcopy PRO assessment was scheduled, consider calling the participant to complete PRO over the phone, or posting the questionnaire to their home address with reply-paid envelope to return completed questionnaire) | 4 | Requires additional staff time and resources | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Blazeby (2003) | |

| Interview-administered questionnaires for very sick participants | 4 | Requires additional staff time | Kaasa (1998), Stewart (1992), Moynihan (1998), Chassany (2002) | ||

| Offer more than one MOA | 2 | May complicate data entry procedures or procedures for returning PRO data | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Gotay (2005) | ||

| Negotiate with the site as to their preferred MOA | 1 | May be infeasible to implement different modes between sites—some sites may have to compromise | Simes (1998) | ||

| Interview-administered MOA | Interview-administered MOA may improve response rates. | 1 | Requires additional staff time and resources | Fowler (1996) | |

| Postal MOA | Complete the baseline assessment in clinic and subsequent assessments by post | 1 | None | Kaasa (1998) | |

| Include postage-paid, self-addressed envelope for easy return of completed questionnaires (when using postal MOA) | 3 | Requires additional staff time and postage costs. May be burdensome for participants to send questionnaires back to researchers. | Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Poulter (1997) | ||

| Patient burden—minimise | Minimise patient burden (general statement) | 8 | None | Aaronson (1990), Hahn (1998), Little, D’Agostino (2012), Macefield (2013), McMillan (2003), Revicki (2005), Walker (2003) | |

| Offer assistance to participants to complete PROs (to reduce burden PRO completion) | Additional assistance—childcare (offer to provide child care for participants’ children so that participants can attend clinic visits in which PRO assessments are scheduled) | 1 | Requires additional resources | Bell (2014) | |

| Additional assistance—travel (offer to arrange or fund travel of participants to the clinic for scheduled PRO assessments) | 1 | Requires additional resources | Bell (2014) | ||

| Avoid the need for a clinic visit where possible | 1 | May be difficult to engage participants away from the clinic | Little, Cohen (2012) | ||

| Offer assistance to complete questionnaire if needed | 1 | Requires additional staff time and resources | Sprague (2003) | ||

| Content | Clear/simple content and instructions of questionnaires | 1 | None | Young, de Haes (1999) | |

| Reduce overlap in questionnaire items | 3 | None | Fallowfield (1998), Walker (2003), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Collect relevant PRO data only | 2 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Little, Cohen (2012) | ||

| Format | Avoid using multiple questionnaires | 1 | None | Chassany (2002) | |

| Avoid written (free text) answers | 1 | None | Friedman (1998) | ||

| Clear/simple format | 6 | None | Conroy (2003), Little Cohen (2012), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Revicki (2005), Sloan (2007) | ||

| Large/clear font | 1 | May increase printing costs if larger font adds pages to the questionnaire booklet | Fairclough (2010) | ||

| Professional format (eg, use study letterhead on printed questionnaires, use consistent formatting, etc) | 3 | None | Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Revicki (2005), Sloan (2007) | ||

| Single-sided printing (some reports suggest that participants are more likely to overlook the underside of questionnaires printed double-sided) | 2 | Environmental burden. May increase printing costs due to additional pages in the questionnaire booklet | Fairclough (2010), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Uniform presentation format (a consistent formatting approach appears more professional and may be easier for participants to follow, potentially reducing risk of participants skipping items inadvertently or due to lack of understanding) | 2 | May not be possible if using more than one questionnaire | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Hurny (1992) | ||

| Length of assessments | Consider participant health—sicker participants will not be able to complete long PRO assessments | 3 | None | Moinpour (1989), Stewart (1992), Young, de Haes (1999) | |

| Fewer assessment time points (ie, PRO assessments that occur regularly may be overly burdensome) | 10 | May sacrifice important information by assessing PRO less often | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Little, Cohen (2012), Chassany (2002), Ganz (1988), Jansen (2013), Revicki (2005), Fallowfield (1998), Hurny (1992), Hao (2010), Steinhauser (2006) | ||

| Fewer pages in e-PROs (eg, minimising the number of clicks between pages may reduce burden) | 1 | None | Cantrell (2007) | ||

| Shorter questionnaire | 18 | Limits the amount of information that can be assessed using PROs | Basch (2012), Basch (2014), Bell (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Chassany (2002), Fairclough (2010), Hjermstad (2012), Hurny (1992), Moinpour (1989), Revicki (2005), Rock (2007), Sadura (1992), Siddiqui (2014), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Use CAT/screening questions (allows for targeted question content and fewer items, to minimise burden) | 1 | Requires additional set-up costs. Can be difficult to introduce a second, non-electronic MOA if using CAT as questions administered will differ between participants | Hjermstad (2012) | ||

| Use validated questionnaires | Questionnaire items or formatting that participants find burdensome may be addressed in response to feedback obtained during questionnaire validation process | 1 | None | Kaasa (1992) | |

| Participant education and engagement (also see table 3) | Continued participant engagement—use strategies to keep participants engaged throughout the life of the study/trial | Adapt procedures to participant cultural group—conduct background research about the cultural groups involved | 2 | Requires time and resources | Wilcox (2001) |

| Participant incentives for participating/completing PRO questionnaires | Offer participants access to care via/after trial/study | 3 | Requires time and resources | Blazeby (2003), Little, Cohen (2012), Little D'Agnostino (2012) | |

| Offer participants financial incentives | 13 | Requires time and resources. Conflicting evidence about the effectiveness (in general population samples)68 and ethical issues in patient populations | Dykema (2012), Gates (2009), Jansen (2013), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Little, Cohen (2012), Meyers (2003), Sherman (2005) | ||

| Offer participants non-financial incentives | 8 | Requires time and resources. Conflicting evidence about the effectiveness (in general population samples)68 and ethical issues in patient populations | Dykema (2012), Little, Cohen (2012), Sherman (2005), Hellard (2001) | ||

| Reimburse participants for their time/costs involved in participating (factor into study budget) | 3 | Requires time and resources | Hellard (2001), Little, Cohen (2012), Senturia (1998) | ||

| Selecting a PRO measure | Acceptable measures for participants | 5 | None | Chassany (2002), Jordhoy (2010), Kaasa (1992), Revicki (2005) | |

| Clinically relevant measures (select PRO measures that are clinically appropriate, that is, include questions about relevant issues to specific disease/treatment) | 7 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Friedman (1998), Ganz (2007), Gheorghe (2014), Hahn (1998), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Features to avoid in prospective PRO measures | Avoid overlapping content/highly correlated items | 2 | None | Beitz (1996), Taphoorn (2010) | |

| Avoid sensitive item content (ie, participants are more likely to skip items addressing sensitive issues such as sexuality or finances; so by avoiding such items you may minimise risk of missing PRO data) | 4 | Participants may have different views about what constitutes sensitive data. Some key issues for particular studies are considered sensitive, for example, sexual function | Fallowfield (1998), Jansen (2013), Pijls-Johannesma (2005), Simes (1998) | ||

| Translated (validated) questionnaires | 2 | Complicates trial set up and implementation, particularly when using e-PROs | Kaasa (1998), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000) | ||

| Validated measures (these are likely to be more clinically relevant and acceptable to patients) | 6 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Blazeby (2003), Fallowfield (1998), Kaasa (1992), Siddiqui (2014) | ||

| Other | Ordering questionnaire items chronologically may speed up completion time and be easier for patients to complete | 1 | We strongly recommend that researchers do not change the item order of validated questionnaires. Questionnaires should be administered in the exact format as validated. | Dunn (2003) | |

| Strategies for measuring sensitive issues (please see Chassany 2002 for a description of various strategies) | 1 | None | Chassany (2002) | ||

| PROs part of trial/larger study | Research team should commit to the PRO substudy (eg, when part of larger trial) | 11 | Requires time and resources | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Chassany (2002), Hayden (1993), Kiebert (1998), Moynihan (1998) | |

| Incorporate PROs in trial/main study design | PROs should be a mandatory/integral part of the trial/ larger study (ie, PRO data are not an optional extra) | 10 | None | Aaronson (1990), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Hayden (1993), Hurny (1992), Kaasa (1992), Movsas (2004), Osoba (2007), Sadura (1992), Siddiqui (2014), Young, de Haes (1999) | |

| Consider logistic factors when designing PRO study | 4 | None | Chassany (2002), Little, D’Agostino (2012), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| PRO content in the study protocol60 61 63 | Define end points/hypotheses (ensure PRO end point is scientifically compelling) | 5 | None | Cella (1994), Fallowfield (2005), Little, Cohen (2012), Taphoorn (2010), Walker (2003) | |

| Specify how missing data will be handled | 1 | May not be possible to fully plan how missing data will be handled prospectively | Calvert (2004) | ||

| Specify the importance of PRO assessment compliance | 1 | None | Fayers (1997) | ||

| Include/plan PRO aspects of the study carefully | 13 | None | Bell (2014), Fayers (1997), Ganz (2007), Hahn (1998), Hao (2010), Land (2007), Moinpour (1998), Movsas (2003), Poy (1993), Revicki (2005), Sloan (2007),Walker (2003) | ||

| Specify plans for minimising missing data (such as those listed in this review) in the protocol | 11 | None | Beitz (1996), BIQSFP (2012), Calvert (2004), Fairclough (2010), Kaasa (1998), Moinpour (1998), Revicki (2005), Simes (1998), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Specify PRO assessment schedule | 2 | None | Hopwood (1996), Moinpour (1998) | ||

| Specify the rationale for PRO assessment (understanding why PROs are being measured and the value the information will bring to the trial is useful for all members of the trial team, and reinforces the importance of high-quality PRO data collection) | 11 | None | Aaronson (1990), Bell (2014), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Conroy (2003), Fayers (1997), Hopwood (1998), Sadura (1992) | ||

| Include PROs in the SAP† | Specify potential problems with PRO analysis in SAP | 2 | May not be possible to predict and prepare for all potential problems with PRO analysis when developing the SAP | Taphoorn (2010), Walker (2003) | |

| Plans for addressing missing data in SAP | 2 | May not be possible to fully plan how missing data will be handled prospectively | Bell (2014), Bernhard, Peterson (1998) | ||

| PROs in other trial/study documents | Include PRO study in relevant sections of procedural documents | 1 | None | Land (2007) | |

| QA | QA—planning ahead | Consider logistic factors when designing PRO study | 1 | None | Fallowfield (2005) |

| Create study databases with QA in mind (ie, consider how PRO data completion rates will be monitored using the database) | 5 | Requires time and resources | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Land (2007), Moinpour (1998), Wisniewski (2006) | ||

| Manage PROs with other trial/study end point data (ie, in a single database) | 2 | Data managers will require additional training for PROs—which requires additional time and resources | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Hurny (1992) | ||

| Describe QA procedures in protocol | 3 | None | Cella (1995), Gheorghe (2014), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Specify QA procedures in a manual | 2 | None | Cella (1994),Cella (1995) | ||

| Establish target PRO compliance rates (ie, quotas that must be achieved, eg, a target of 95% indicates that no more than 5% of missing PRO questionnaires will be tolerated) | 6 | None | Hahn (1998), Little, Cohen (2012), Little, D’Agostino (2012), McMillan (2003), Sloan (2007) | ||

| Sample (for PRO data collection) | PRO subsample (if study power permits and if the study budget or logistics limit capacity to collect PROs from all participants, consider collecting PROs from a subsample only) | PRO data from representative subsample of the trial population | 2 | May be difficult administratively, particularly for site staff to implement | Simes (1998) |

| Do not collect PROs from patients with advanced disease | 1 | QOL issues are often of very important in patients with advanced disease. | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | ||

| Allow patients/sites to opt in to the PRO study | 1 | May lead to selection bias if sites or participants opt-in to PRO study | Simes (1998) | ||

| May also lead to impression that PRO study is of lesser importance than other study outcomes | |||||

| Recruit motivated patients only | 2 | May lead to selection bias if only motivated participants take part in PRO study | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Simes (1998) | ||

| Separate (additional) consent for PRO study | 1 | Requires additional time and resources | Simes (1998) | ||

| Sample size | Increase sample size to allow for attrition | 7 | The rate of missing data is important, regardless of whether the available data meet sample size requirements. Although increasing sample size will improve study power in the case of low PRO completion rates, the outcomes of participants with missing PRO data may differ to those with complete PRO data—which may lead to bias. | Altman (2007), Kaasa (2002), Little, D’Agostino (2012), Sherman (2005), Stewart (1992), Tang (2002), Jordhoy (2010) | |

| Team—design/protocol development | Involve committees (to review PRO study) | Ethics review | 1 | None | Movsas (2003) |

| PRO committee (ie, some trials groups have a dedicated PRO committee, comprised of PRO research specialists who review and provide feedback on PRO aspects of trials) | 6 | Requires access to a trials group with resources for a PRO committee | Hahn (1998), Osoba (1992), Osoba (2007), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Multidisciplinary team involved in design/protocol development (each party brings unique and complementary expertise and experiences to improve the design of the PRO study) | Involve a multidisciplinary team in PRO study design | 6 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Kiebert (1998), Moinpour (1998) | |

| Involve experienced investigators in PRO study design (to offer strategies for maximising compliance, selection of informative measures and time points, and other key aspects of study design) | 2 | None | Little, Cohen (2012), Little, D’Agostino (2012) | ||

| Involve nurses in PRO study design (to offer expertise about patient experiences and relevant QOL issues, clinic environment, data collection, etc) | 1 | None | Hayden (1993) | ||

| Involve patients in PRO study design (to comment on the acceptability and relevance of PRO questionnaires, suitability of assessment time points in capturing desired outcomes, patient burden, strategies to educate and engage participants, and many other important aspect of study design) | 3 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Hurny (1992), Moynihan (1998) | ||

| Involve PRO experts in PRO study design (to offer strategies for maximising compliance, selection of informative measures and time points, analysis and interpretation strategies and other key aspects of study design) | 3 | None | Fallowfield (1998), Kiebert (1998), Basch (2014) | ||

| Involve site coordinators in PRO study design (to offer expertise about logistics of PRO assessment, patient experiences and relevant QOL issues, data collection strategies, etc) | 4 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Hayden (1993), Larkin (2012), Moinpour (1998), Cella (1995) | ||

| Support the site staff | Minimise institution/staff burden (an overly burdensome PRO assessment schedule or procedure for site staff is likely to lead to high rates of missing data) | 6 | None | Aaronson (1990), Young, de Haes (1999) |

*Some sources may have provided a recommendation more than once.

†This review only covers proxy reporting as a strategy to facilitate interpretation of missing PRO data. If considering using proxies, please consult the literature for a review of additional challenges and implementation strategies.

CAT, computer-adaptive testing; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ePRO, PROs administered electronically; MOA, mode of administration; PRO, patient-reported outcome; QA, quality assurance; QOL, quality of life; SAP, statistical analysis plan.

The five most frequently recommended design strategies were: baseline PRO completion as an eligibility criterion (n=28), develop guidance for site staff to standardise the administration of PRO questionnaires(n=27), minimise the length of questionnaires to reduce patient burden (n=18), align PRO assessment time points to clinic visits (n=16) and ensure recruiting sites have sufficient resources to run the PRO study (n=15).

Implementation strategies to minimise the problem of missing PRO data

Recommendations for minimising the problem of missing PRO data while the PRO study is active were coded into seven categories in table 3: administration procedures: standardised procedures, particularly for site staff, to maximise PRO compliance; patient education and engagement: education about the value of PROs in the study, and engagement through study updates or incentives; maintaining patient records: contact details and health status should be kept updated; quality assurance: procedures and active communication to monitor compliance and intervene if issues are apparent; site coordinator: appoint an individual responsible for PRO assessment at recruiting sites with appropriate organisational and communication skills; team involved in study implementation: broader trial team must stay engaged and committed to the PRO study, and work together towards its successful completion; and staff training: provide initial and ongoing training about PROs, communication skills, methodology; and formats of such training. The most frequently recommended implementation strategies were: use a PRO completion cover sheet for standardised recording of reasons for missing PRO data (n=39), appoint a site coordinator responsible for PRO assessments (n=33), send reminders about upcoming PRO assessments to site staff (n=30), ensure site staff check completed PRO questionnaires for missed items while the patient is still in the clinic (n=29) and centrally monitor PRO compliance in real-time (n=27).

Table 3.

Study conduct strategies to minimise the problem of missing PRO data

| Category | Topic | Specific recommendation | N recommendations* | Potential drawbacks | Source/s: first author (year). Full citations are provided as Online Supplementary Appendix C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration procedures | Approach all participants | All participants involved in the PRO study should be approached to complete scheduled PRO assessments, including those who are very ill (Site staff should not make any decisions about who is able to complete PROs as this may lead to selection bias. The decision is the participant’s.) | 11 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Fairclough (2010), Hopwood (1998), Bakitas (2009), McMillan (2003), Revicki (2005), Young, de Haes (1999), Aaronson (1990), Moynihan (1998) |

| Assistance completing PRO measures | Prespecify types/levels of assistance that may be provided to participants | 5 | None | Fayers (1997), Kaasa (2002), Revicki (2005), Young, de Haes (1999), Fairclough (2010) | |

| Offer assistance to participants who need it | 11 | Requires additional staff time | Aaronson (1990), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Fayers (1997), Friedman (1998), Hurny (1992), Jordhoy (2010), Bakitas(2009), Macefield (2013), Repetto (2001), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Record levels of assistance provided | 1 | None | Blazeby (2003) | ||

| Nominate who should provide assistance to participants | 3 | Requires additional time and resources | Cella (1995), Revicki (2005), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Be organised | Ensure sufficient questionnaires available for use | 1 | None | Moynihan (1998) | |

| Prepare for upcoming assessments (have questionnaires ready) | 6 | None | Vantongelen (1989), Cella (1995), Coates (1998), Moinpour (1989), Revicki (2005), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Prepare to handle potential problems | 1 | None | Revicki (2005) | ||

| Track when PRO assessments due | 5 | None | Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Checking | Checking for missed PRO items | 29 | None | Calvert (2004), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Chassany (2002), Davies (1994), Fallowfield (1998), Fayers (1997), Fowler (1996), Friedman (1998), Ganz (1988), Hayden (1993), Hopwood (1998), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Kyte (2013), Moinpour (1990), Moinpour (1998), Movsas (2003), Movsas (2004), Revicki (2005), Taphoorn (2010), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | |

| Checking source data (data entry; when entering questionnaire data into database) | 2 | None | Davies (1994), Poy (1993) | ||

| Ensure patients receive questionnaires (particularly when the patients complete questionnaires outside of clinic) | 1 | None | Kaasa (1998) | ||

| PRO completion cover sheet (a form on which site staff can record whether PROs were completed and if not completed, the possible reason why) | Importance of cover sheet | 1 | None | Moinpour (1998) | |

| Recording levels of assistance | 6 | Requires additional time and resources to collect | Fayers (1997), Fairclough (2010), Fayers (1997), Moinpour (1998), Hopwood (1998), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Standardised reasons for missing data (possible reasons for non-completion of PROs may be listed on a cover sheet for the convenience of site staff and for ease of data collection) | 39 | Requires additional time and resources to collect | Fairclough (2010), Fayers (1997), Moinpour (1998), Hopwood (1998), Revicki (2005), Bell (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Blazeby (2003), Calvert (2004), Curran (1998), Fairclough (2010), Fallowfield (1998), Fayers (1997), Hahn (1998), Hao (2010), Kiebert (1998), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Land (2007), Little, Cohen (2012), Luo (2008), Moinpour (1990), Moinpour (1998), Revicki (2005), Simes (1998), Taphoorn (2010), Walker (2003), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Reasons for missing PRO data may not be easy to determine in some cases. | |||||

| Missed assessments | Alternative mode of administration (if participants miss a PRO assessment, contact the participant to capture the data using an alternative mode. Also see table 2 ‘Mode of administration’) | 17 | Requires additional staff time and resources. Potential for bias based on setting of completion (systematic differences between modes, particularly if one mode is interview administered, and the other is completed by patient66) | Basch (2014) Calvert (2004), Cella (1995), Fairclough (2010), Fowler (1996), Hopwood (1996), Hurny (1992), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Land (2007), Moinpour (1990), Revicki (2005), Stewart (1992), Walker (2003), Revicki (2005) | |

| Following up missed assessments | 18 | Requires additional staff time and resources | Cella (1994), Cella (1995),Conroy (2003), Fowler (1996), Hopwood (1998), Huntington (2005), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Movsas (2003), Movsas (2004), Sherman (2005), Sprague (2003), Sprangers (2002), Taphoorn (2010), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Specify place of PRO completion (eg, quiet spot in the clinic) | 8 | May be difficult to offer a quiet place to complete questionnaires in busy clinic environment | Calvert (2004), Hurny (1992), Jansen (2013), Moynihan (1998), Sadura (1992), Sherman (2005), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Returning questionnaires | Specify procedures for returning questionnaires | 1 | None | Poulter (1997) | |

| Time of completion | Standardise time of completion (eg, first thing when the patient arrives at the clinic) | 2 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Fayers (1997) | |

| Before seeing clinician (many sources recommended PROs should be completed before the participants have their appointment with their clinician) | 4 | Requires advanced planning and potential negotiation with clinician to ensure PRO assessment is complete prior to the clinic appointment. Difficulties may arise if scheduled PRO assessments do not align with clinic visits. | Fayers (1997), Sprague (2003), Young, de Haes (1999), Hopwood (1998) | ||

| Standardised methods | Adhere to PRO assessment schedule | 2 | None | Moinpour (1998), Poulter (1997) | |

| Use standard administration methods | 5 | None | Cella (1995), Chassany (2002), Movsas (2003), Movsas (2004), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Standardise methods (eg, by developing written guidance) | 13 | Time and minimal costs involved initially | Bernhard, Gusset (1998), Cella (1995), Chassany (2002), Fayers (1997), Gheorghe (2014), Hopwood (1998), Moinpour (1998), Movsas (2003), Movsas (2004), Osoba (2007), Poy (1993), Revicki (2005), Sadura (1992) | ||

| Thank the participant | On completion of questionnaire (face-to-face) | 6 | None | Calvert (2004), Kyte (2013), Meyers (2003), Sherman (2005), Steinhauser (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | |

| Thank you letters | 3 | Requires additional time and resources | Steinhauser (2006), Fallowfield (1998), Poulter (1997) | ||

| Train staff | – | – | See ‘Train staff’ category | ||

| Participant education and engagement | Confidentiality | Be mindful of sensitive PRO data (ensure participants understand it will be kept confidential) | 2 | None | Cella (1994), Sherman (2005) |

| Discuss family involvement (participants may not wish to disclose certain information if they believe family members may see the data) | 1 | None | Sherman (2005) | ||

| Inform participants that PRO data are kept confidential | 6 | None | Calvert (2004), Fallowfield (1998), Movsas (2003), Sherman (2005), Simes (1998), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Sealed envelopes (allow participants to self-seal so they are assured of the confidentiality of data) | 1 | Prevents site staff from being able to check for any missing items | Fallowfield (1998) | ||

| Strategies for continued participant engagement | Site staff should offer to answer participant questions | 3 | None | Calvert (2004), Fayers (1997), Hurny (1992) | |

| Awareness of culturally sensitive issues | 1 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | ||

| Match staff to participant cultural group (Some participants may build rapport more easily if they liaise with a coordinator from the same cultural group.) | 1 | May not be possible/feasible for all studies | Cella (1995) | ||

| Build rapport with participants | 4 | None | Blazeby (2003), Steinhauser (2006) | ||

| Educate participants about PROs (importance of PROs, how PRO data are used, how to complete PROs) | 5 | Requires staff time and commitment—depending on the comprehensiveness of education offered | Basch (2012), Fairclough (2010), Gotay (2005), Huntington (2005), Kaasa (1998) | ||

| Provide clear/simple instructions for completion of PRO assessments | 5 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Calvert (2004), Chassany (2002), Hurny (1992), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Encourage participants to ask for questionnaire when they are due (in case site staff forget) | 2 | None | Fayers (1997), Hopwood (1998) | ||

| Ensure participants understand (PRO assessment/how to complete questionnaires, etc) | 8 | Requires staff time, | Moinpour (1990), Moinpour (1998), Muller-Buh (2011), Poulter (1997), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Collect information about participants at risk of dropping out and use that information to intervene, or implement intensive follow-up strategies for these participants | 4 | Risk of drop out may be difficult to predict in some samples. | Little, D’Agostino (2012), Senturia (1998),Sprague (2003) | ||

| Maintain contact with participants | 4 | Requires staff time, resources and commitment | Hellard (2001), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Senturia (1998), Wisniewski (2006) | ||

| Send participants PRO assessment reminders | 16 | Requires staff time, resources and commitment | Altman (1993), Basch (2012), Bell (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Cella (1998), Fallowfield (1998), Jansen (2013), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Land (2007), Revicki (2005), Sherman (2005), Sprague (2003), Wisniewski (2006) | ||

| Provide assistance to participants when required | 1 | Requires staff time, resources and commitment | Fairclough (2010) | ||

| Provide encouragement to participants when completing PROs | 4 | Requires staff time, resources and commitment | Basch (2012), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Little, Cohen (2012), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Explain reason for multiple PRO assessments | 4 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Calvert (2004), Hurny (1992), Sprague (2003) | ||

| Explain and remind participants of importance of PROs | 11 | None | Fayers (1997), Kyte (2013), Taphoorn (2010), Wilcox (2001), Calvert (2004), Cella (1995), Chassany (2002), Conroy (2003), Hellard (2001), Sherman (2005) | ||

| Update participants on trial/study progress | 6 | Requires staff time, resources and commitment | Cella (1995), Hellard (2001), Little, Cohen (2012), Sadura (1992) | ||

| Informed consent (ensure these aspects of PRO study are addressed) | Instruct participants to answer honestly/no right or wrong answers | 1 | None | Young T, de Haes (1999) | |

| Inform participants that assistance is available if needed | 1 | None | Young T, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Explain commitment involved for the PRO study | 7 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Blazeby (2003), Hurny (1992), Sherman (2005), Sprague (2003), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Explain PRO assessment during informed consent process | 5 | None | Fallowfield (1998), Fayers (1997), Hopwood (1998), Movsas (2003), Moynihan (1998) | ||

| Explain importance of PRO assessment | 14 | None | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Conroy (2003), Fairclough (2010), Fayers (1997), Friedman (1998), Hurny (1992), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Blazeby (2003), Revicki (2005),Taphoorn (2010), Walker (2003), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Explain importance of complete PRO data | 5 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Little, Cohen (2012), Young T, de Haes (1999), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Explain that participation is voluntary | 1 | None | Sherman (2005) | ||

| Language translations available (participants may feel more confident using an alternative language translation that the default language offered) | 1 | None | Young T, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Ensure participant understands | 3 | None | Ganz (1988), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Participants can take information sheets home. | 3 | None | Fayers (1997), Land (2007) | ||

| Recruitment method | Face-to-face recruitment | 2 | None | Jansen (2013) | |

| Follow the recruitment protocol | 1 | None | Senturia (1998) | ||

| Less aggressive recruitment methods may be more effective than more assertive methods. | 2 | May result in reduced recruitment. Recruitment method should not be aggressive, not lax. | Hellard (2001), Kaasa (1998) | ||

| Participant records | Obtain contact details at registration | Alternate contact (a close relative or friend who you can contact in case the participant cannot be reached) | 5 | Some participants may not have a trusted friend/relative to nominate as alternate contact. Alternate contact person will need to provide consent to be contacted—which may be difficult to obtain and/or implement. | Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Senturia (1998), Sherman (2005) |

| Obtain complete participant contact details | 1 | Participant contact details may change during the course of the study; therefore, contact details should be checked regularly. | Sprague (2003) | ||

| Specify procedures for checking and updating participant records | 3 | None | Cella (1995), Moinpour (1990), Senturia (1998) | ||

| Update participant records | Check if participant is alive (It may be distressing for friends/family members if study reminder letters are posted to participants home after they have died. This situation can be avoided by contacting the participant's doctor for updates on the participant’s condition.) | 2 | Must be handled carefully if participants’ relatives are contacted, and may require formal approval if participants’ GPs are contacted | Fallowfield (1998), Hopwood (1996) | |

| Update participant contact details | 6 | Requires time and resources | Kleinpell-Nowell (2000), Little, Cohen (2012), Little, D’Agostino (2012), Meyers (2003), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Record successful strategies for contacting participants (so that these strategies may be used for future study contact) | 1 | None | Meyers (2003) | ||

| Quality assurance | Central monitoring for PROs | Central office monitors compliance | 4 | Requires planning and resources to implement | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Hayden (1993), Kiebert (1998), Land (2007) |

| Appoint a central PRO coordinator/QA officer | 12 | Requires additional resources | Bell (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Fallowfield (1998), Hahn (1998), Hurny (1992), Land (2007), Moinpour (1990), Poy (1993), Simes (1998), Sloan (2007) | ||

| Real-time monitoring of PRO completion (enables prompt intervention if PRO assessments are missed) | 27 | Requires time, commitment and resources of site and central monitoring staff. Requires input from database developers and statisticians from set-up phase. Difficult to implement for multisite trials due to delays in obtaining PRO forms from sites, and differences between patients in recruitment time | Basch (2012), Basch (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Gusset (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Ganz (2007), Hayden (1993), Huntington (2005), Kyte (2013), Little, Cohen (2012), Movsas (2003), Poy (1993), Revicki (2005), Siddiqui (2014), Sprague (2003), Walker (2003), Wilcox (2001), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Communication | Central monitors should discuss participants who withdraw with site staff (this may identify potential issues with site management and potential strategies for avoiding problems in future). | 1 | Requires real-time compliance monitoring, which requires time, commitment and resources of central and site staff | Sprague (2003) | |

| Discuss the role of site staff in responding to participants’ medical needs | 1 | None | Sherman (2005) | ||

| Central office should send feedback reports to sites on PRO compliance and reasons for missing PRO data (this may assist sites to recognise problematic patterns in missing data, and to work towards rectifying such issues). | 14 | Requires real-time compliance monitoring, which requires time and resources of central staff | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Land (2007), Friedman (1998), Hahn (1998), Hurny (1992), Senturia (1998), Wilcox (2001), Young, de Haes (1999), Young, Maher (1999) | ||

| Sites should send feedback to central office (problems, participant feedback, etc, which may be able to be addressed through discussion, in future protocol amendments or in future studies) | 3 | Time commitment | Bernhard, Gusset (1998), Hopwood (1998) | ||

| Importance of regular communication between research team | 20 | Requires time and resources | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Calvert (2004), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Hayden (1993), Land (2007), Moinpour (1998), Moynihan (1998), Osoba (1992), Poy (1993), Wisniewski (2006), Young, de Haes (1999) | ||

| Regular meetings (a forum for communication between the research team) | 6 | Requires time and resources | Cella (1994), Land (2007), Moinpour (1989), Osoba (1996), Sprague (2003), Wisniewski (2006) | ||

| Share strategies for successful PRO compliance | 3 | None | Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Calvert (2004), Kleinpell-Nowell (2000) | ||

| Schedule when reports are due for the sites to communicate with the central office | 1 | None | Cella (1995) | ||

| Reward high performing sites/staff | Document methods of success (regarding high PRO completion rates) | 1 | None | Stewart (1992) | |

| Offer financial incentives to sites for high completion rates | 5 | Costs involved | Little, D’Agostino (2012), Ganz (2007), Little, Cohen (2012), Aaronson (1990), Bernhard, Gusset (1998) | ||

| Offer incentives to sites for high completion rates (type of incentive unspecified) | 4 | Costs involved | Basch (2012), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Cella (1995), Hurny (1992) | ||

| Offer National Cancer Institute (NCI, USA) credit as incentive | 2 | Costs involved | Land (2007) | ||

| Offer non-financial incentives | 1 | Costs involved | Little, D’Agostino (2012) | ||

| Site coordinator authorship as incentive | 1 | Costs involved | Moinpour (1998) | ||

| Thank you letters to site staff | 1 | Time and costs involved | Land (2007) | ||

| Travel support to high performing site staff as incentive | 2 | Costs involved | Hahn (1998) | ||

| Poorly performing sites | Intervene in poorly performing sites (ie, with additional training, discussion about support needed to improve completion rates, etc) | 4 | Requires real-time compliance monitoring, and time and resources to implement interventions | Bernhard, Gusset (1998), Hahn (1998), Hahn (1998), Land (2007) | |

| Introduce incentives if improvement is seen at poorly performing sites | 1 | Costs involved. Need to be introduced before compliance rates fall too low. | Cella (1994) | ||

| Penalise sites for poor compliance (eg, eliminate opportunity for future recruitment/involvement in future trials) | 5 | May reduce morale at that site if not handled appropriately | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Hayden (1993), Land (2007), Moinpour (1998) | ||

| Terminate recruitment at poorly performing sites | 2 | May reduce number of patients eligible for recruitment | Fayers (1997), Poy (1993) | ||

| QA should be in place to promote high completion rates | – | 10 | Requires commitment and resources to implement | Bell (2014), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Cella (1995), Moinpour (1989), Moinpour (1998), Osoba (2007), Poy (1993), Revicki (2005) | |

| Rate site's performance and assess against benchmark compliance rates | 1 | Requires real-time compliance monitoring, which requires central staff time and resources | Land (2007) | ||

| Site-level monitoring | Sites should be prepared for regulator inspections | 1 | Requires time and commitment of site and central staff | Poy (1993) | |

| Sites should also monitor their own compliance rates | 1 | Requires time and resources | Hahn (1998) | ||

| Support for sites/staff | Offer ongoing training to site staff | 4 | Time and costs involved | Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Hahn (1998), Revicki (2005) | |

| Send site staff reminders (for upcoming/overdue PRO assessments) | 32 | Requires time and resources | Basch (2012), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Fairclough (2010), Hahn (1998), Hayden (1993), Hurny (1992), Land (2007), Moinpour (1989), Moinpour (1998), Osoba (1992), Poulter (1997), Revicki (2005), Sadura (1992), Siddiqui (2014), Simes (1998), Vantongelen (1989) | ||

| Site coordinator | Appoint a site coordinator—an individual at each site responsible for PRO administration for the study | 34 | Costs involved | Beitz (1996), Bernhard, Cella (1998), Bernhard, Peterson (1998), Blazeby (2003), Calvert (2004), Cella (1994), Cella (1995), Conroy (2003), Fallowfield (1998), Fayers (1997), Ganz (1988), Gotay (2005), Hahn (1998), Hayden (1993), Hopwood (1998), Hurny (1992), Kaasa (1992), Kyte (2013), Moinpour (1989), Moinpour (1990), Muller-Buh (2011), Poulter (1997), Revicki (2005), Stewart (1992), Young, de Haes (1999) | |

| Roving coordinator (Rural/remote centres may have too few participants to warrant appointing a dedicated site coordinator. Instead a roving coordinator may be responsible for several such sites.) | 1 | Costs involved | Scott (2004) | ||

| May be difficult to implement if rural centres are geographically distant, and if participants have similar PRO assessment schedules | |||||

| Nominate a back-up site coordinator (If a primary site coordinator is absent, this individual will take responsibility for the trial.) | 3 | Requires additional resources to ensure back-up coordinator is adequately trained and informed about the PRO study | Calvert (2004), Fayers (1997), Revicki (2005) | ||

| Characteristics of site coordinator | Committed to the study | 2 | None | Blazeby (2003), Larkin (2012), Moinpour (1998) | |

| Site staff should be accommodating/flexible | 7 | The flexibility of site staff is limited by their individual schedules and the resources available at the site | Senturia (1998), Sherman (2005), Sprague (2003) | ||

| Interpersonal skills | 1 | Interpersonal skills cannot always be taught | Bernhard, Cella (1998) | ||

| Languages spoken (if the site has participants from multiple language backgrounds, it may be crucial to employ a coordinator who can speak these language/s) | 1 | May be difficult to recruit multilingual site coordinators | Bernhard, Peterson (1998) | ||

| Positive attitude | 8 | Difficult to train staff to have a positive attitude. Ascertaining and intervening in such problems may be difficult to implement. | Bernhard, Cella (1998), Fairclough (2010), Kaasa (1992), Larkin (2012), Revicki (2005), Scott (2004), Sherman (2005) | ||

| Team involved in study implementation | Commitment to the PRO study—required of the entire trial team, specifically: | Central office staff | 1 | May require some education about the value and importance of complete PRO data—which may require additional time and resources | Osoba (2007) |

| Physicians | 2 | May require some education about the value and importance of complete PRO data—which may require additional time and resources | Hurny (1992), Vantongelen (1989) | ||