Abstract

Two recent large-scale sequencing studies have identified multiple genetic aberrations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. These findings offer substantial insights that may spur the development of new diagnostics and treatments for these cancers.

Large-scale sequencing efforts have facilitated the dawn of a new era in deciphering the molecular basis of pediatric brain tumors. Only a short time ago, these tumors were collectively considered a veritable ‘black box’ of ill-defined pathological entities. In the past year, new mutations in medulloblastoma1–3 and driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin-remodeling factor genes in pediatric glioblastoma4,5 have been identified, providing key insights for the development of novel treatments for affected patients. Low-grade gliomas (LGGs) commonly affect children and include World Health Organization (WHO) grade I pilocytic astrocytomas, grade II diffuse gliomas and other entities such as pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas (PXAs) and gangliogliomas. Whereas most pilocytic astrocytomas have a favorable prognosis, LGGs that cannot be completely resected ultimately cause significant morbidity and mortality, despite their slow growth. Even though previous studies have linked LGGs to the abnormal activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)–extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) pathway6, little was known about the specific genetic alterations driving this pathway. Now, two independent genomic studies from David Ellison and colleagues7 and Stefan Pfister and colleagues8 provide the first clear overview of the genomic landscape of lower grade pediatric gliomas.

Many roads, one destination

Zhang et al.7 report whole-genome, transcriptome and targeted high-throughput sequencing of pediatric lower grade tumors. Overall, few genetic alterations were identified, with a median of only a single alteration per tumor. In agreement with previous studies9,10, Zhang et al.7 confirmed the presence of KIAA1549-BRAF fusions that lack the portion of BRAF encoding its regulatory domain, leading to constitutive BRAF activation, in 59% of pilocytic astrocytomas and BRAFV600E mutations in 70% of PXAs. They further identified new rearrangements and amplifications of MYB in 25% of diffuse cerebral gliomas. Intriguingly, they found recurrent intragenic duplications of the region of FGFR1 encoding the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) in 24% of diffuse grade II cerebral gliomas. In theory, these duplications would bring together two tyrosine kinase domains, obviating the need for receptor dimerization to activate signaling. When the investigators orthotopically transplanted Tp53-null astrocytes expressing TKD-duplicated FGFR1, all mice developed high-grade astrocytomas with complete penetrance. Within these tumors, two pathways downstream of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) activation, the MAPK-ERK and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways, were both aberrantly activated. Likewise, ectopic expression of TKD-duplicated FGFR1 in vitro resulted in FGFR1 autophosphorylation and activation of both MAPK-ERK and PI3K pathways. Notably, selective FGFR inhibitors blocked the autophosphorylation of TKD-duplicated FGFR1, thus providing a rationale for targeting FGFR1 or its downstream effectors in pediatric LGGs. In addition to duplications, missense mutations in FGFR1 and FGFR-TACC fusions were also identified that can activate the MAPK-ERK and PI3K pathways.

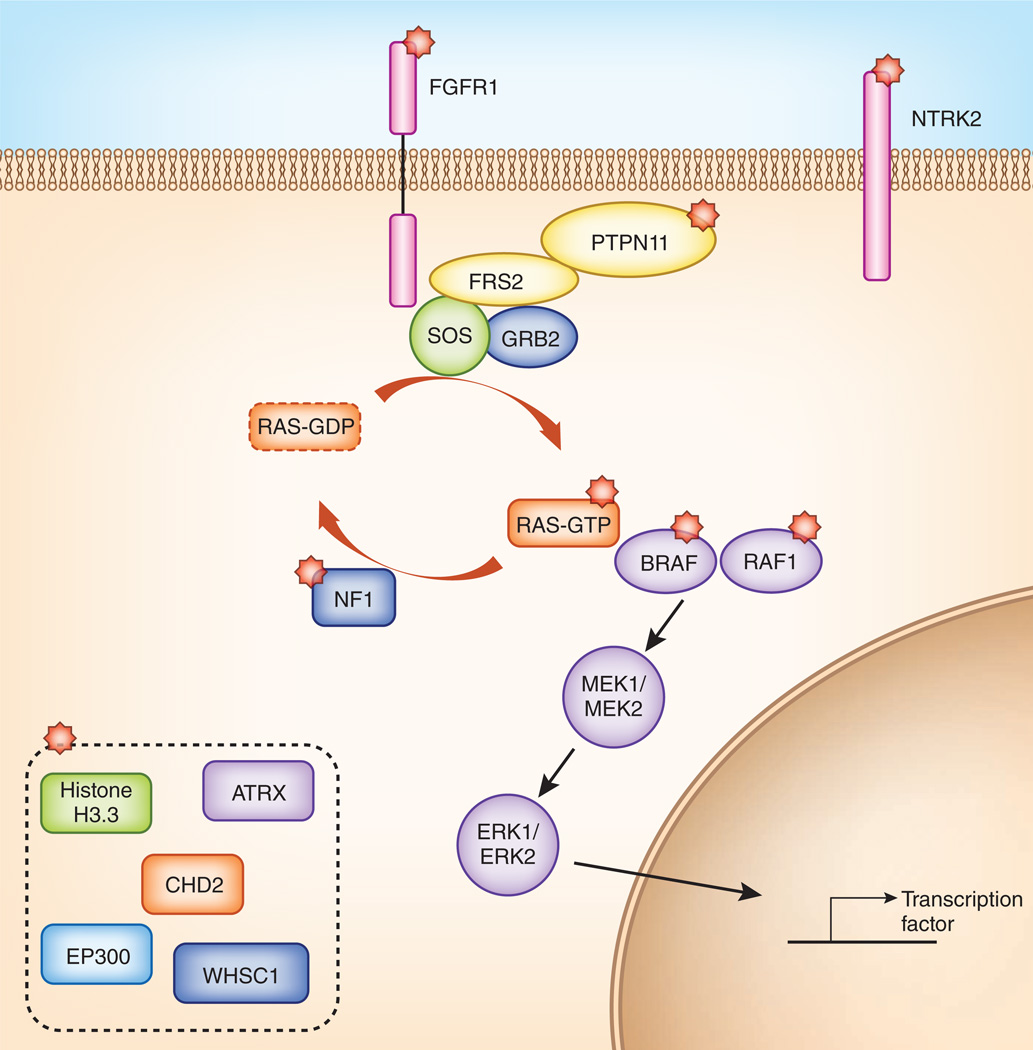

In an independent study, Jones et al.8 sequenced 96 pilocytic astrocytomas and also noted an extremely low rate of mutation. They reported the presence of KIAA1549-BRAF fusion variants, along with four new BRAF fusions and a single three-amino-acid insertion in the interdomain cleft of BRAF, which increased ERK phosphorylation as effectively as the BRAFV600E mutation. Interestingly, in the 19% of non-cerebellar tumors that lacked an alteration in BRAF or KRAS, new NTRK2 gene fusions affecting its kinase domain were identified. The resulting chimeric tyrosine kinases probably mediate ligand-independent dimerization, leading to a dominantly acting oncoprotein and potentially activating the MAPK pathway. Jones et al. also uncovered FGFR1 aberrations and identified mutations and duplications affecting the kinase domain of FGFR1, along with mutations in the tyrosine phosphatase PTPN11. Notably, PTPN11 alterations were only present in a subset of FGFR1-mutant tumors, suggesting a cooperative role for these factors in tumorigenesis. Notably, all of the pilocytic astrocytomas harbored a MAPK pathway alteration, and, with the exception of the co-occurrence of mutations in FGFR1 and PTPN11, each case harbored only one alteration in the pathway per tumor. Taken together, data from Jones et al. and Zhang et al. suggest that pediatric LGGs can have differing genomic alterations that ultimately converge so as to achieve activation of a few common signaling pathways (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The majority of genetic alterations in pediatric LGGs activate the MAPK-ERK pathway. MAPK pathway components with alterations identified in the studies by Zhang et al.7 and Jones et al.8 are indicated with red stars. Several factors linked to histone modification were also found to have genetic abnormalities in a small subset of samples (dashed box). These findings offer insight into novel approaches to targeted therapeutics for pediatric LGGs.

It remains to be seen whether alterations in the epigenome contribute to pediatric LGGs. Both studies indicated that, unlike adult LGGs, in which hotspot mutations in IDH1 or IDH2 are found in more than 70% of tumors11,12 and tend to co-occur with TP53 and ATRX mutations or with 1p or 19q loss13–15, pediatric LGGs are mainly driven by genetic aberrations that activate kinase signaling. At least, from what we know so far, driver mutations in the epigenetic machinery seem to be reserved for higher grade pediatric glioblastomas5. Indeed, Jones et al. identified only one FGFR1-mutant tumor that also had a mutation affecting histone H3.3. These findings indicate a small degree of overlap between the genes that drive pediatric LGGs and those that drive higher grade gliomas. It remains to be seen whether such overlapping mutations can serve as prognostic factors for progression.

Are we there yet?

The data described above significantly advance understanding of these once-enigmatic tumors. However, much work remains. In comparison to adult LGGs, malignant transformation is less frequent for pilocytic astrocytomas and certain other lower grade tumors in children. It is unclear whether this difference is due to the relatively stable nature of pediatric LGG cancer genomes, to differing cells of origin for these two cancers or to other unknown factors. If a pediatric LGG recurs, does it accumulate more mutations and remain distinct from its adult counterpart? Future studies are needed to shed light on these important questions.

The findings of Zhang et al.7 and Jones et al.8 converge on the hypothesis that, despite the mutational heterogeneity among different tumors, genetic alterations in LGGs commonly lead to the activation of the MAPK-ERK and PI3K pathways. This observation suggests the existence of a degree of biological homogeneity, which opens the door to developing better treatment options. In the near future, we will need to assess the response of affected patients to agents that target these pathways and explore possible mechanisms of resistance should this occur. Ultimately, it is tantalizing to envision a treatment paradigm for pediatric gliomas similar to that for other cancer types driven primarily by distinct kinases, as with the kinase inhibitors used to target BCR-ABL in chronic myelogenous leukemia. In the event that novel, effective treatment options come to fruition, it would be clear that the studies described here provided the direction needed to allow affected patients to successfully navigate their disease and treatment.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jones DT, et al. Nature. 2012;488:100–105. doi: 10.1038/nature11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rausch T, et al. Cell. 2012;148:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson G, et al. Nature. 2012;488:43–48. doi: 10.1038/nature11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu G, et al. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:251–253. doi: 10.1038/ng.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartzentruber J, et al. Nature. 2012;482:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfister S, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1739–1749. doi: 10.1172/JCI33656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, et al. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:602–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DTW, et al. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:927–932. doi: 10.1038/ng.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sievert AJ, et al. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:449–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schindler G, et al. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan H, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turcan S, et al. Nature. 2012;483:479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XY, et al. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:615–625. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannan K, et al. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1194–1203. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiao Y, et al. Oncotarget. 2012;3:709–722. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]