Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Safe, effective weight loss with resolution of comorbidities has been convincingly demonstrated with bariatric surgery in the aged obese. They, however, lose less weight than younger individuals. It is not known if degree of weight loss is influenced by the choice of bariatric procedure. The aim of this study was to compare the degree of weight loss between laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in patients above the age of 50 years at 1 year after surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective analysis was performed of all patients more than 50 years of age who underwent LSG or LRYGB between February 2012 and July 2013 with at least 1 year of follow-up. Data evaluated at 1 year included age, sex, weight, body mass index (BMI), mean operative time, percentage of weight loss and excess weight loss, resolution/remission of diabetes, morbidity and mortality.

RESULTS:

Of a total of 86 patients, 54 underwent LSG and 32 underwent LRYGB. The mean percentage of excess weight loss at the end of 1 year was 60.19 ± 17.45 % after LSG and 82.76 ± 34.26 % after LRYGB (P = 0.021). One patient developed a sleeve leak after LSG, and 2 developed iron deficiency anaemia after LRYGB. The remission/improvement in diabetes mellitus and biochemistry was similar.

CONCLUSION:

LRYGB may offer better results than LSG in terms of weight loss in patients over 50 years of age.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, elderly, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, weight loss

INTRODUCTION

The epidemic of obesity has emerged rapidly in the Asia Pacific region over the last 20 years. As per the World Health Organization (WHO) World Health Statistics 2012 report, 1 in 6 adults is obese and 1 in 10 is diabetic.[1] A recent study in the urban population of India demonstrated that 6.8% are obese [>30 body mass index (BMI)] and 33.5% are overweight (25-30 BMI).[2] The prevalence of morbid obesity is also rising sharply amongst the elderly patients.[3] With the additional burden of comorbidities in the elderly, quality of life deteriorates further. Effective weight loss and resolution of comorbidities has been convincingly demonstrated with bariatric surgery. Concerns regarding increased perioperative complications earlier led to reluctance to offer bariatric surgery to older patients.[4] There is increasing evidence in the published literature for the safety profile of bariatric surgery performed in such a subgroup of patients.[5] However, aged obese individuals lose less weight than younger individuals.[6]

Among the various surgical options, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) remain the most commonly performed surgeries worldwide. It is not known if the degree of weight loss achieved by aged obese individuals can be improved by the choice of bariatric procedure. Recently, LSG has been increasingly popular among surgeons and patients due to its safety profile and reproducibility. Although the results of LSG seem to be comparable to LRYGB in the general population, the same has not been made in the elderly group (>50 years) of the population.

The aim of this study was to compare the degree of weight loss between LSG and LRYGB in patients above the age of 50 years at 1 year after surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A retrospective analysis was performed using a prospectively maintained database. All obese elderly patients over the age of 50 years who underwent LSG or LYRGB between February 2012 and July 2013 and with at least 1 year of follow-up were included in the study.

As this was a retrospective study, approval from the hospital Ethics Committee was not required. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for including them in the study. No identifying information is included in this article.

Selection for bariatric procedure

Our institution is a tertiary care referral hospital providing advanced procedures in gastrointestinal surgery, with a dedicated department for bariatric surgery. At our institution, all patients selected for bariatric surgery are required to meet National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for eligibility for bariatric surgery.

The choice of bariatric procedure (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy) was based on the individualised goals of therapy [i.e., weight loss and/or metabolic (glycaemic) control], presence of associated nutritional risks, presence of gastro-oesophageal reflux and patient preferences. If metabolic (glycaemic) control was needed, the choice of bariatric procedure was based on severity and duration of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and preoperative C peptide levels.

In general, a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was advised only to patients with long-standing, severe diabetes with lower preoperative C peptide levels and in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. In the rest of the patients, a LSG was advised. Occasionally, the procedure planned was changed according to patient preferences and in the presence of associated nutritional risks. This resulted in the choice of LSG in a majority of the patients over LRYGB.

Surgical techniques

Surgical weight loss operations were carried out using the laparoscopic approach in all patients. The bariatric surgeries included in this study were the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and the sleeve gastrectomy. These were combined with cholecystectomy and ventral hernia repair (anatomical repair or intraperitoneal mesh repair) when indicated for gallstones and ventral hernias.

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

The five-port technique was used. The gastro-colic and gastro-splenic omentum was divided from the greater curvature close to the stomach using a Harmonic Ace device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) or a Ligasure device (Covidien Ltd, Norwalk, Connecticut, USA). The sleeve was created over a 38-Fr bougie starting 5 cm proximal to the pylorus. Multiple applications of a linear stapler using green, blue or gold loads were used to excise the stomach. An intraoperative air leak test was performed as a routine.

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB)

An ante-colic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was performed with an approximately 30-mL gastric pouch. A 75-cm biliopancreatic limb and an alimentary limb in the range of 75-150 cm were created. The jejunojejunostomy was constructed in a side-to-side, stapled manner with single firing of a 60-mm laparoscopic linear stapler, with closure of enterotomy using intracorporeal suturing. The gastrojejunal anastomosis was constructed with a linear stapler on the posterior wall and then closed by intracorporeal hand suturing. The gastrojejunal stoma is approximately 2.5 cm. No drains were used in either group. Gastrograffin study was done in all cases.

Follow-up schedule and supplementation

We routinely follow up patients at 15 days, 1 month, 1.5 months, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and thereafter 1-yearly after surgery. Single multi-vitamin supplementation was recommended for sleeve gastrectomies. Twice-daily multi-vitamin supplementation and calcium/vitamin D3 supplementation were recommended after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with screening to prevent iron and vitamin B12 deficiencies.

Outcome measures

Data evaluated at 1 year included age, sex, weight, BMI, mean operative time, weight loss, resolution/remission of diabetes, re-admissions, morbidity and mortality.

Weight loss

Body weights were measured at 1 week pre-surgery and 12 months post-surgery. Excess body weight was defined as measured body weight minus the body weight that would result in a BMI of 25 kg/m2, which in simple terms would mean measured body weight minus ideal body weight (IBW). Weight loss outcome measures used were percentage of excess weight loss, percentage of weight loss and BMI loss.

Diabetes control

Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), requirement of insulin and oral hypoglycaemic agents (OHA) were also recorded at 1 week pre-surgery and 12 months post-surgery. Diabetes was considered resolved in patients who had normal fasting blood glucose (FBG) (≤110 mg/dL), who had a normal HbA1c, and who required no diabetic medications after surgery. Patients were considered improved if there was significant improvement in FBG (by >25 mg/dL) or if there was a significant reduction of HbA1c (by >1%), or if there was a significant reduction in diabetes medication or dose (by discontinuing one agent or 1/2 reduction in dose).

Complications

Short-term complications were divided into major and minor complications. Major complications were defined as those directly related to the operation, such as anastomotic or staple line leak, haemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, inadvertent injury to other organs, postoperative venous thromboembolism or pulmonary complications. Minor complications were defined as non–life-threatening events that include superficial skin or soft-tissue infection, incisional haematoma, urinary tract infection or musculoskeletal problems. Long-term complications were defined as nutritional complications at follow-up. Mortality was recorded, and 30-days and 1-year mortality rates were calculated.

Analysis of study population

The study population was divided into two groups. Group I was composed of patients who underwent LSG and Group II of patients who underwent LRYGB. Comparative analysis of BMI and percentage excess weight loss between the two groups of patients was performed using the independent Student t test. Improvement/remission of diabetes was expressed as categorical variables and changes were assessed using the chi-square test. SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 20 was used for statistical analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Two hundred ninety-one patients underwent bariatric surgery at our institution between February 2012 and July 2013. Two hundred twenty received LSG and 71 received LRYGB. Of these, 86 patients who were >50 years of age with at least 1 year of follow-up were included in the study.

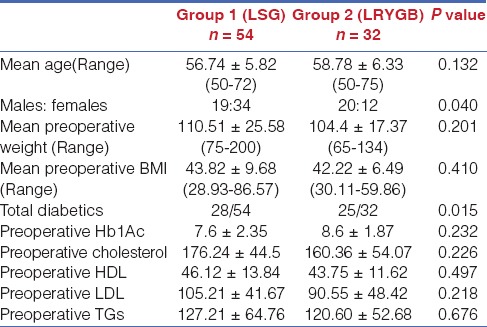

Of the 86 patients, 54 patients (Group 1) had received LSG and 32 patients (Group 2) had received LRYGB. Details of demography, anthropometry, comorbidities and biochemistry at the time of surgery in both groups are provided in Table 1. Both the groups were comparable in terms of demographic profile, as shown in Table 1. There were more females among those in whom a LSG was performed, and more diabetics among those in whom a LRYGB was performed.

Table 1.

Details of demography, anthropometry, co-morbidities and biochemistry at the time of surgery in the study population

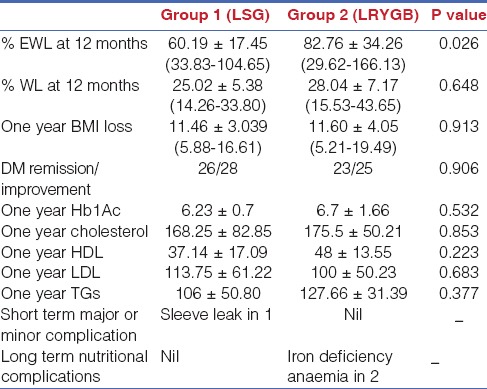

Details of weight loss outcomes, improvement of comorbidities and biochemistry in both groups are provided in Table 2. The mean percentage of excess weight loss at the end of 1 year was 60.19 ± 17.45% for Group I versus 82.76 ± 34.26% for Group II (P = 0.021). A total of 28 patients had T2DM in Group I with 26 patients resolved at 1 year. Two patients with long-standing diabetes on insulin showed improvement at 1 year. Twenty-five patients in Group II had T2DM, with 23 patients resolved at 1 year. Two patients with long-standing diabetes on insulin showed improvement at 1 year. There was no difference in diabetes resolution or improvement in biochemistry. There was one sleeve leak in Group I and no major complications in Group II. There were 2 patients with iron deficiency anaemia on long-term follow-up in Group II.

Table 2.

Details of weight loss outcomes, improvement of comorbidities and biochemistry at one year in the study population

DISCUSSION

With increasing rates of obesity in the elderly, weight management becomes an important but difficult aspect for this subset of individuals. The reasons are attributable to an increasing prevalence of comorbidities and, more importantly, the associated physical and cognitive disability. Bariatric surgery has developed to be the primary treatment option for the morbidly obese who fail lifestyle interventions.[7] There are sufficient data on the efficacy of these surgical procedures on weight reduction and remission of the associated comorbidities. Bariatric surgery at most centres is limited to patients <65 years of age for many reasons.[7] Scozzari et al. had reported age as an important prognostic factor in bariatric surgery and recommended that surgical indications in patients >50 years be carefully weighed.[8] Age is considered to be an independent prognostic factor in addition to BMI, presence of diabetes mellitus and smoking in predicting postoperative mortality.[9] Santo et al. had reported increased incidence of postoperative thromboembolism in the elderly.[10] Further, increased postoperative morbidity and mortality rates in the elderly, as reported by Flum et al. and Livingston and Langert et al., have been a concern among surgeons in the context of the safety of procedures in the elderly.[4,11]

With improvement in anaesthetic techniques, standardisation of surgical procedures and better patient selection, there are now sufficient data on the safety and efficacy of the bariatric surgical procedures in the elderly. Ramirez et al. had shown bariatric surgeries can be safely performed even in patients >70 years of age with a low rate of complications and acceptable improvement of comorbidities.[12] Although the elderly patients (>65 years) had a slightly prolonged hospital stay, Dorman et al. had reported no increased morbidity or mortality compared to the younger population.[13] Willkomm et al. reported no differences in postoperative complications between patients above and less than 65 years of age.[5] A recent meta-analysis of 1206 elderly patients operated for morbid obesity reported a mortality rate of 0.25%, which is comparable to the mortality rates published by the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Consortium for a younger cohort of patients (0.3%).[14] Most of the available data on bariatric surgery for patients >50 years have been for either LRYGB or LAGB.[15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] In the meta-analysis by Lynch et al., perioperative complication rates and mortality were higher in the LRYGB group compared to the LAGB group.[27] At the same there was better weight loss at 6 months and 12 months and significantly better comorbidity resolution in the LRYGB group.[27] Since its inception, LSG has evolved to be an acceptable standalone procedure for morbid obesity. A randomised controlled trial by Keidar et al. had shown no difference in excess weight loss or resolution of comorbidities compared to LRYGB.[28] Yaghoubian et al. had shown comparable morbidity and mortality and, although insignificant, better weight loss in the sleeve gastrectomy group.[29] Vidal et al. had shown similar short- and mid-term weight loss between the two procedures and, more importantly, reduced complications rates in the sleeve gastrectomy group.[30] With the advantages of easier reproducibility, better morbidity profile and comparable outcomes to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy is gaining increasing acceptance worldwide. The safety and efficacy of LSG have also been demonstrated in the elderly group. The results of Van Rutte et al. and Soto et al. have shown LSG to be a relatively safe and effective procedure in terms of weight loss and comorbidity resolution in the elderly.[31,32] Considering the safety profile and better results, LSG has emerged to be a better alternative to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and LAGB, as suggested by Carlin et al.[33] However, the efficacy of LSG has been questioned by a few authors. A recent meta-analysis by Li et al. has shown Roux-en-Y gastric bypass to be more effective to LSG, in both weight loss and resolution of comorbidities.[34] Thus, controversies continue to exist. In addition, there exist very limited data on the comparison of these procedures in the patient groups over 50 years of age.

Our study addresses the latter fact and has shown that LRYGB with % EWL of 82.76% at 12 months was significantly better compared to LSG with % EWL of 60.19%. The results of sleeve gastrectomy were similar to those reported from other centres. Soto et al. had shown 55% EWL with LSG at the end of 12 months with the usage of 38-Fr bougie.[31] Van Rutte et al. had reported % EWL of 52.6% at the end of 14 months in the elderly patients with LSG.[32] The results after LRYGB were higher than those after LSG, as reported from other centres. Fazylov et al. reported a 69.5% EWL at 12 months after LRYGB in patients >55 years.[15] Sosa et al. reported a mean EWL of 65% at 12 months after LRYGB in patients >55 years.

In this study, the percentage of total weight loss and BMI loss was also higher in those with LRYGB in comparison to LSG; however, our findings highlight the well-known discrepancy of very significant differences in %EWL versus no significant differences in total weight loss and BMI reduction between the two groups. Several statistical and clinical reasons can be implicated for this disparity. It has been shown that the percentage of excess weight loss varies significantly based on initial BMI, i.e., the higher the BMI of the patient, the lower the percentage of excess weight loss. This effect is further magnified by short follow-up, which does not allow sufficient time for higher-BMI individuals to lose sufficient weight to reach their nadir. This variation by initial BMI disappears using percentage of total weight loss.[35] However, on using percentage of total weight loss instead of percentage of excess weight loss, a very significant correlation with postoperative weight is not found although differences are still demonstrated as in our study further supporting our findings.

Our study thus highlights the fact that in patients with no pre-existing nutritional deficiencies, and with otherwise no contraindication for a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, LRYGB will ensure better weight loss without any additional morbidity. However, the major limitations of our study are that it was a retrospective study with a small number and a short follow-up of only 1 year. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the impact of different bariatric procedures in elderly obese patients.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, bariatric surgery is an effective procedure for weight loss and can be safely performed even in the elderly. Although LSG has emerged as a standalone bariatric procedure with comparable results to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the general population, our study shows that LRYGB may offer significantly better weight loss than LSG with no added morbidity.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

All the authors declare no financial disclosure and no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. World Health Statistics 2012. WHO. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 16]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2012/en/

- 2.Unnikrishnan AG, Kalra S, Garg MK. Preventing obesity in India: Weighing the options. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:4–6. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.91174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirani V, Zaninotto P, Primatesta P. Generalised and abdominal obesity and risk of diabetes, hypertension and hypertension-diabetes co-morbidity in England. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:521–7. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JA, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1903–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willkomm CM, Fisher TL, Barnes GS, Kennedy CI, Kuhn JA. Surgical weight loss >65 years old: Is it worth the risk? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:491–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Kellum JM, Sugerman EL, Meador JG, Wolfe LG. Effects of bariatric surgery in older patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:243–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133361.68436.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scozzari G, Passera R, Benvenga R, Toppino M, Morino M. Age as a long-term prognostic factor in bariatric surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;256:724–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182734113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padwal RS, Klarenbach SW, Wang X, Sharma AM, Karmali S, Birch DW, et al. A simple prediction rule for all-cause mortality in a cohort eligible for bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:1109–15. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santo MA, Pajecki D, Riccioppo D, Cleva R, Kawamoto F, Cecconello I. Early complications in bariatric surgery: Incidence, diagnosis and treatment. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:50–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032013000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livingston EH, Langert J. The impact of age and medicare status on bariatric surgical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1115–21. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez A, Roy M, Hidalgo JE, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients >70 years old. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:458–62. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorman RB, Abraham AA, Al-Refaie WB, Parsons HM, Ikramuddin S, Habermann EB. Bariatric surgery outcomes in the elderly: An ACS NSQIP study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:35–44. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1749-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:445–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazylov R, Soto E, Merola S. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in morbidly obese patients > or =55 years old. Obes Surg. 2008;18:656–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9364-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papasavas PK, Gagn® DJ, Kelly J, Caushaj PF. Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y gastric bypass is a safe and effective operation for the treatment of morbid obesity in patients older than 55 years. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1056–61. doi: 10.1381/0960892041975541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sosa JL, Pombo H, Pallavicini H, Ruiz-Rodriguez M. Laparoscopic gastric bypass beyond age 60. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1398–401. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Peter SD, Craft RO, Tiede JL, Swain JM. Impact of advanced age on weight loss and health benefits after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Arch Surg. 2005;140:165–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trieu HT, Gonzalvo JP, Szomstein S, Rosenthal R. Safety and outcomes of laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery in patients 60 years of age and older. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:383–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wittgrove AC, Martinez T. Laparoscopic gastric bypass in patients 60 years and older: Early postoperative morbidity and resolution of comorbidities. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1472–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9929-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busetto L, Angrisani L, Basso N, Favretti F, Furbetta F, Lorenzo M. Italian Group for Lap-Band. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the elderly. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:334–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abu-Abeid S, Keidar A, Szold A. Resolution of chronic medical conditions after laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding for the treatment of morbid obesity in the elderly. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:132–4. doi: 10.1007/s004640000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clough A, Layani L, Shah A, Wheatley L, Taylor C. Laparoscopic gastric banding in over 60s. Obes Surg. 2011;21:10–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor CJ, Layani L. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in patients > or =60 years old: Is it worthwhile? Obes Surg. 2006;16:1579–83. doi: 10.1381/096089206779319310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frutos MD, Luján J, Hernández Q, Valero G, Parrilla P. Results of laparoscopic gastric bypass in patients > or =55 years old. Obes Surg. 2006;16:461–4. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silecchia G, Greco F, Bacci V, Boru C, Pecchia A, Casella G, et al. Results after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in patients over 55 years of age. Obes Surg. 2005;15:351–6. doi: 10.1381/0960892053576622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch J, Belgaumkar A. Bariatric surgery is effective and safe in patients over 55: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1507–16. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0693-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keidar A, Hershkop KJ, Marko L, Schweiger C, Hecht L, Bartov N, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for obese patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1914–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaghoubian A, Tolan A, Stabile BE, Kaji AH, Belzberg G, Mun E, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy achieve comparable weight loss at 1 year. Am Surg. 2012;78:1325–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vidal P, Ramón JM, Goday A, Benaiges D, Trillo L, Parri A, et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a definitive surgical procedure for morbid obesity. Mid-term results. Obes Surg. 2013;23:292–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soto FC, Gari V, de la Garza JR, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Sleeve gastrectomy in the elderly: A safe and effective procedure with minimal morbidity and mortality. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1445–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0992-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Rutte PW, Smulders JF, de Zoete JP, Nienhuijs SW. Sleeve gastrectomy in older obese patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2014–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlin AM, Zeni TM, English WJ, Hawasli AA, Genaw JA, Krause KR, et al. Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182879ded. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li JF, Lai DD, Ni B, Sun KX. Comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Surg. 2013;56:E158–64. doi: 10.1503/cjs.026912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van de Laar A, de Caluw® L, Dillemans B. Relative outcome measures for bariatric surgery. Evidence against excess weight loss and excess body mass index loss from a series of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21:763–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]