Abstract

Objectives

To measure the incidence of urinary incontinence over 10 years among older women who did not report urinary incontinence at baseline in 1998. We also estimated the prevalence of female urinary incontinence, by severity and type and explored potential risk factors for development.

Design

A secondary analysis of a prospective cohort

Participants

Women participating in the Health and Retirement Study, between 1998 and 2008 including only female participants who did not have urinary incontinence at baseline (1998).

Measurements

We defined urinary incontinence as an answer of “Yes” to the question, “During the last 12 months, have you lost any amount of urine beyond your control?” Incontinence was characterized by severity, according to the Sandvik Severity Index, and type, according to International Continence Society definitions, at each biennial follow-up between 1998 and 2008.

Results

In 1998, 5,552 women ages 51 to 74 years old reported no urinary incontinence. The cumulative incidence of urinary incontinence in older women was 37.2% (95%CI 36.0%, 38.5%). The most common incontinence type at the first report of leakage was mixed urinary incontinence (49.1%; 95%CI 46.5%, 51.7%) and women commonly reported their symptoms at first leakage as moderate to severe (46.4%; 95%CI 43.8%, 49.0%).

Conclusion

Development of urinary incontinence in older women was common and tended to result in mixed type and moderate to severe symptoms.

Keywords: epidemiology, natural history, urinary incontinence

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common condition associated with depression, social isolation and poor self-rated health in older women.(1, 2) Among community-dwelling adult women, UI prevalence estimates range from 30 to 60% and increase with age.(3, 4) The majority of epidemiologic studies have focused on measuring UI symptoms at a single-time point or incidence over a short time period.(5-7) Fewer studies have obtained data at regular intervals over longer time periods to delineate the natural history of UI symptoms.

Three secondary analyses of large prospective cohorts have examined urinary symptoms in women over 6 to 10 years, mostly surrounding the menopausal transition.(8-10) In a study of U.S. women through the menopausal transition, average annual incidence of UI was 11.1% over 6 years. (8) Over the 6 years surrounding the menopausal transition, 14.7% of women reported worsening of urinary symptoms and 32.4% reported improvement of symptoms.(11) Another population-based study of women aged 40 to 44 in Norway, reported on women's urinary symptoms over 10 years.(10) Two-year incidence of UI ranged from 12% to 14.5%.(10) Finally, in an older cohort of women aged 70-75 years, 14% (95% confidence interval (CI) 13.9-15.3) of women developed new incontinence symptoms over the 9 years of follow-up.(9) These studies demonstrate that urinary symptoms are dynamic and changes in women's urinary symptoms are common.

Improved knowledge of long-term natural history of UI by type and severity, especially in community-dwelling older women after the menopausal transition, is needed. In this study, we measured the incidence of UI over 10 years among older women who did not report UI at baseline in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative cohort. We also estimated the prevalence of UI, by severity and type, over 10 years. Finally, we examined potential risk factors at baseline for development of UI.

Methods

Design

We performed a secondary analysis of the HRS, a prospective cohort of over 30,000 older adults funded by the National Institutes on Aging and conducted by the Institute for Social Research (ISR) at the University of Michigan. Written exemption for this study (#1205010299) was obtained from the Yale University Institutional Review Board on 6/4/2012.

Setting

The HRS was first launched in 1992 and follows participants with in-person interviews conducted by trained research personnel every 2 years.(12)

Participants

The overall response rate for the HRS is 87 to 89%.(12) We included in our analytic sample all female participants in the 1998 HRS who did not have UI at baseline (in 1998). We then followed these women through the subsequent biennial datasets for the next 10 years until 2008. We then excluded women who died between 1998 and 2008 (n = 940) or who dropped out (n=216). A total of 5,552 women were included in our analysis.

Measurement of UI

We defined UI as women who answered “Yes” to the question, “During the last 12 months, have you lost any amount of urine beyond your control?” We utilized responses about urinary symptoms from the 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008 HRS datasets. Women were categorized into one of four distinct categories: no UI (no UI reported at any time), UI with fluctuation (UI reported at least once, but never had 2 consecutive reports of UI), UI with persistence (2 consecutive follow-ups with UI), and uncategorized (unable to classify due to missing data). Missing data on UI symptoms on at least one of the 5 follow-up questionnaires were present in 986 women. Of these 986 women with missing UI data, 117 women could be clearly classified as either UI with fluctuation or UI with persistence according to definitions. The remaining 869 women could not be clearly assigned and were classified as uncategorized.

We further characterized UI by severity and type at each time point. To categorize UI severity, we used the Sandvik Severity Index (SSI) using the modification proposed by Komesu et al. for the HRS answer responses.(6,13) Higher scores indicated worse incontinence. Scores of ≥ 3 are considered moderate to severe incontinence. Type of UI was categorized based on International Continence Society definitions of responses to two questions. Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) was defined by answers of “most of the time” or “some of the time” to the question, “[H]ow often did you leak with an urge to urinate and could not get to the bathroom fast enough?” Stress urinary incontinence was defined as answers of “most of the time” or “some of the time” to the question “[H]ow often did you leak with activities such as coughing, laughing or sneezing?” Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) was defined as women who had both SUI and UUI.

Measurements of potential risk factors

We examined demographics and clinical characteristics that could be associated with the development of UI. These characteristics included age category in 1998 (51 to 56 years old (war baby cohort), 57 to 67 years old (HRS cohort), and 68 to 74 years old (CODA cohort)), self-reported race/ethnicity, current smoking status, parity and obesity category. In addition, we summed seven major medical comorbidities including hypertension, heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, cancer, lung disease, and arthritis. Medical comorbidity was examined as a dichotomous variable (≥3 vs. < 3). Functional status was assessed by asking women about6 basic activities of daily living (ADLs). The composite functional status measure combined the responses of all 6 ADLs as a single variable. Having a functional limitations was defined as difficulty or dependence with ≥1 ADL. Finally, depressive symptoms were measured utilizing the short-form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale modified for the HRS.(14)

Analyses

Statistical analyses, including descriptive and inferential statistics with percentage estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI), were performed as appropriate (F-test for continuous variables, Rao-Scott χ2 test for categorical variables). We estimated the prevalence (exact 95% Confidence Intervals (CI)) of UI, including by severity (mild, moderate/severe), type (stress, urgency and mixed) and age category (CODA, HRS, and War Babies), in 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, & 2008. We estimated the cumulative incidence of UI every 2 years over the 10 years of follow-up by dividing the total number of women who had ever reported UI during follow-up by the total number of women in the study population. We estimated the incidence rate (95% CI) of new onset UI (per 1,000 person-year) at each two year follow-up using modified Poisson regression.(15) We also estimated the 10-year cumulative incidence rate of UI among every 1,000 person-years. Analyses for UI prevalence and incidence were conducted only among women with non-missing UI data (e.g. missing data was not imputed).

The HRS dataset allowed data to be weighted to provide an estimate of population characteristics representative of community-dwelling older Americans (birth year cohorts from 1924 to1947). Percentage estimates and 95% CI were reported as weighted percentages. A multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to explore potential risk factors (in 1998) for UI symptom category (UI with fluctuation, and UI with persistence) ten years later (in 2008) among the 4,683 women who clearly fit into one of the three categories. Potential risk factors were included in the final model based on their significance in univariate analysis (p ≤.1). Sensitivity analyses were then performed. For the 869 uncategorized women who could not be clearly classified into one of the three UI categories (No UI, UI with fluctuation or UI with persistence) due to the missing information on UI symptoms at one or more follow-ups, we randomly assigned the missing UI variable as “Yes” or “No” with probability of 50% of each. Thus, all 5552 women had the outcome variable defined. We repeated this random imputation process 10,000 times, estimating an odds ratio each time. The odds ratios (50th, 2.5th, and 97.5th percentiles) from the 10,000 runs including all 5,552 women were then compared to the odds ratios from the primary analysis conducted among the 4,683 women who had clearly fit into one of the three UI categories. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

In 1998, there were 5,552 female participants in the HRS ages 51 to 74 years old who reported no UI symptoms and were included in our analysis. Forty-nine percent of women (95%CI 48.0%-50.6%) never reported UI at any time in the 10 years of follow-up. UI symptoms were variable in women with incident UI; 970 women (17.5%; 95%CI 16.5-18.5) reported UI with fluctuation and 977 women (17.6%; 95%CI 16.6-18.6) reported UI with persistence.(Table 1) Women who developed incident UI (with fluctuation or persistence) were older, more likely to be obese or have functional limitations, and had more medical co-morbidities compared with women who remained continent. (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Women (in 1998) (N=5,552).

| Characteristics | No UI (N=2736) |

UI with fluctuation (N=970) |

UI with persistence (N=977) |

Uncategorized (N=869) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted, Percent (95%CI) or Mean (SEM) | N | Weighted, Percent (95%CI) or Mean (SEM) | N | Weighted, Percent (95%CI) or Mean (SEM) | N | Weighted, Percent (95%CI) or Mean (SEM) | P value | |

| Age(Year), Mean(SEM) | 2736 | 59.7 (0.2) | 970 | 60.4 (0.3) | 977 | 60.6 (0.3) | 869 | 59.5 (0.3) | 0.001 |

| Age Category | 0.002 | ||||||||

| CODA (68 to 74 years old) | 495 | 18.2 (15.7, 20.7) | 220 | 22.5 (19.7, 25.2) | 236 | 23.8 (19.8, 27.9) | 163 | 19.2 (16.1, 22.4) | |

| HRS (57 to 67 years old) | 1537 | 43.7 (41.7, 45.6) | 534 | 43.9 (40.8, 46.9) | 519 | 41.3 (38.7, 43.8) | 451 | 39.8 (36.1, 43.5) | |

| War Babies (51 to 56 years old) | 704 | 38.1 (35.6, 40.6) | 216 | 33.6 (30.1, 37.2) | 222 | 34.9 (30.6, 39.2) | 255 | 40.9 (36.8, 45.0) | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 2129 | 84.0 (81.4, 86.6) | 780 | 85.0 (81.9, 88.1) | 849 | 89.9 (87.6, 92.2) | 642 | 79.5 (75.8, 83.3) | |

| Black | 485 | 11.3 (9.8, 12.8) | 156 | 11.0 (8.6, 13.3) | 104 | 7.4 (5.7, 9.1) | 181 | 14.5 (11.8, 17.1) | |

| Other | 122 | 4.7 (3.2, 6.2) | 34 | 4.0 (2.3, 5.8) | 24 | 2.7 (1.3, 4.0) | 46 | 6.0 (3.9, 8.1) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 237 | 7.4 (5.1, 9.8) | 95 | 8.6 (4.8, 12.3) | 79 | 6.5 (4.3, 8.8) | 96 | 9.4 (6.8, 12.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Other | 2499 | 92.6 (90.2, 94.9) | 875 | 91.4 (87.7, 95.2) | 898 | 93.5 (91.2, 95.7) | 773 | 90.6 (88.0, 93.2) | |

| Marital Status | 0.9 | ||||||||

| Married | 1876 | 65.0 (62.6, 67.5) | 680 | 67.1 (63.7, 70.4) | 666 | 65.0 (61.2, 68.8) | 593 | 63.7 (59.6, 67.9) | |

| Divorced or Separated | 366 | 16.4 (14.7, 18.2) | 127 | 15.3 (12.3, 18.2) | 125 | 15.3 (11.8, 18.8) | 118 | 15.6 (12.3, 18.9) | |

| Widowed | 410 | 15.1 (13.6, 16.6) | 140 | 14.8 (12.2, 17.5) | 155 | 16.0 (13.3, 18.8) | 125 | 15.8 (13.0, 18.6) | |

| Never Married | 80 | 3.3 (2.5, 4.2) | 21 | 2.6 (1.2, 3.9) | 29 | 3.5 (2.1, 5.0) | 33 | 4.9 (3.0, 6.7) | |

| Education | 0.7 | ||||||||

| Less than High School | 626 | 19.5 (16.6, 22.4) | 241 | 21.3 (18.8, 23.9) | 189 | 17.3 (14.2, 20.4) | 226 | 22.4 (19.9, 24.9) | |

| High School or Equivalent | 1097 | 39.6 (37.0, 42.3) | 370 | 38.8 (35.3, 42.3) | 407 | 40.7 (36.6, 44.9) | 348 | 41.5 (38.1, 44.8) | |

| Some College | 563 | 22.5 (20.3, 24.7) | 211 | 22.1 (19.2, 25.1) | 215 | 22.6 (19.1, 26.2) | 178 | 21.5 (18.5, 24.5) | |

| Bachelor's Degree or Higher | 447 | 18.2 (15.9, 20.4) | 148 | 17.7 (15.3, 20.2) | 165 | 19.3 (16.4, 22.3) | 117 | 14.6 (11.9, 17.4) | |

| Parity | 0.2 | ||||||||

| 0 | 156 | 7.1 (6.0, 8.2) | 45 | 5.1 (3.5, 6.7) | 53 | 6.3 (4.7, 7.9) | 41 | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | |

| ≥1 | 2556 | 92.9 (91.8, 94.0) | 914 | 94.9 (93.3, 96.5) | 907 | 93.7 (92.1, 95.3) | 821 | 94 (92.0, 96.0) | |

| BMI Category | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <30 | 2087 | 79.1 (77.1, 81.1) | 650 | 70.4 (67.5, 73.3) | 660 | 69.2 (65.1, 73.4) | 655 | 77.8 (75, 80.6) | |

| ≥30 | 598 | 20.9 (18.9, 22.9) | 296 | 29.6 (26.7, 32.5) | 296 | 30.8 (26.6, 34.9) | 191 | 22.2 (19.4, 25) | |

| Number of co-morbidities | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <3 | 2456 | 91.2 (89.9, 92.4) | 793 | 83.6 (80.5, 86.7) | 793 | 83.0 (79.9, 86.0) | 770 | 90.6 (88.4, 92.8) | |

| ≥3 | 280 | 8.8 (7.6, 10.1) | 177 | 16.4 (13.3, 19.5) | 184 | 17.0 (14.0, 20.1) | 99 | 9.4 (7.2, 11.6) | |

| Functional Limitations | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Independent | 2467 | 91.1 (89.6, 92.6) | 794 | 83.0 (79.9, 86.0) | 790 | 82.1 (78.6, 85.6) | 798 | 92.2 (89.8, 94.7) | |

| ≥1 Limitation | 266 | 8.9 (7.4, 10.4) | 176 | 17.0 (14.0, 20.1) | 186 | 17.9 (14.4, 21.4) | 65 | 7.8 (5.3, 10.2) | |

| Current Smoker (Yes) | 459 | 18.0 (15.7, 20.2) | 155 | 17.9 (14.6, 21.3) | 174 | 19.1 (16.0, 22.3) | 169 | 20.6 (17.6, 23.5) | 0.8 |

| CES-D score Mean(SEM) | 2684 | 1.3 (0.1) | 949 | 1.6 (0.1) | 960 | 1.7 (0.1) | 826 | 1.5 (0.1) | <0.001 |

N = unweighted

CI = confidence interval

SEM-standard error of the Mean

Uncharacterized-Unable to be classified into No UI, UI with fluctuation, or UI with persistence due to missing data on at least one of the follow-ups

CODA- children of the depression (birth year 1924-1930)

HRS- original health and retirement survey (birth year 1931-1941)

War babies- (birth year 1942-1947)

BMI- body mass index

IQR-interquartile range

CES-D-Center for epidemiologic studies-depression

The prevalence of UI increased over time. (Table 2) The prevalence of UI in 2000, two years after baseline measurements, was 11.1% (95%CI 10.3%-12.0%) and in 2008, ten years after baseline measurements, was 24.9% (95%CI 23.7%-26.1%). Mixed UI was the most common type of UI that developed. The prevalence of UI was higher among older versus younger women. (Table 2) Mixed urinary incontinence did not tend to develop out of stress or urge alone. The most common UI type at the first report of UI was mixed UI (49.1%; 95%CI 46.5%-51.7%), rather than stress alone (20.1%; 95%CI 18.1%-22.2%) or urge alone (16.9%; 95%CI 15.0%-18.9%). Moderate to severe UI also did not tend to develop from mild UI symptoms. At the first report of UI, women commonly reported their urine leakage as moderate to severe (46.4%; 95%CI 43.8%-49.0%), rather than mild (23.9%; 95%CI 21.8%-26.2%) or uncategorized (29.7%; 95%CI 27.4%-32.1%). The cumulative incidence of UI over 10-years was 37.3% (95%CI 36.0%-38.5%). The 2-year incidence rate of new UI among women who previously did not report symptoms varied between 50.6 per 1,000 person-years (95%CI 46.4-55.2) and 69.5 per 1,000 person-years (95%CI 64.2-75.1). (Table 2) The 10-year cumulative incidence rate of UI was 430 (95%CI 417-445) per 1,000 UI-free persons.

Table 2.

Prevalence and Incidence of Urinary Incontinence among Women without Incontinence in 1998

| 2000 N =5,295 |

2002 N = 5,240 |

2004 N = 5,118 |

2006 N = 5,052 |

2008 N = 4,995 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point estimate of prevalence of UI (95% CI) * | 11.1% (10.3%, 12.0%) | 14.7% (13.8%, 15.7%) | 17.4% (16.4%, 18.5%) | 20.3%(19.2%, 21.4%) | 24.9%(23.7%, 26.1%) | |

| Type of UI | Not available at 2000 | |||||

| Stress | 3.7% (3.2%, 4.2%) | 4.0% (3.5%, 4.6%) | 3.9%(3.3%, 4.4%) | 4.6%(4.0%, 5.2%) | ||

| Urge | 2.0% (1.6%, 2.4%) | 2.9% (2.4%, 3.4%) | 4.0%(3.5%, 4.6%) | 5.2%(4.6%, 5.9%) | ||

| Mixed | 6.8% (6.1%, 7.5%) | 8.5% (7.7%, 9.3%) | 10.1%(9.3%, 11.0%) | 11.8%(10.9%, 12.7%) | ||

| Uncategorized | 2.2% (1.8%, 2.6%) | 2.0% (1.6%, 2.4%) | 2.4%(2.0%, 2.8%) | 3.3%(2.8%, 3.8%) | ||

| Severity of UI | ||||||

| Mild (1-2) | 3.6% (3.1%, 4.2%) | 3.8% (3.2%, 4.3%) | 3.8% (3.3%, 4.3%) | 5.1% (4.5%, 5.8%) | ||

| Mod/Sev (>=3) | 7.5% (6.8%, 8.3%) | 9.0% (8.3%, 9.9%) | 11.3% (10.4%, 12.2%) | 14.1% (13.1%, 15.1%) | ||

| Uncategorized | 3.6% (3.1%, 4.1%) | 4.6% (4.0%, 5.2%) | 5.2% (4.6%, 5.9%) | 5.7% (5.0%, 6.3%) | ||

| Age Category | ||||||

| CODA | 12.2% (10.3%, 14.3%) | 18.2% (15.9%, 20.6%) | 20.6% (18.2%, 23.3%) | 24.5% (21.8%, 27.2%) | 30.4% (27.6%, 33.4%) | |

| HRS | 10.5% (9.4%, 11.6%) | 13.9% (12.7%, 15.3%) | 17.0% (15.6%, 18.4%) | 19.2% (17.8%, 20.8%) | 24.3% (22.7%, 25.9%) | |

| War Babies | 11.7% (10.0%, 13.6%) | 13.6% (11.8%, 15.6%) | 15.7% (13.8%, 17.9%) | 19.3% (17.2%, 21.6%) | 21.7% (19.4%, 24.1%) | |

| Incidence rate at each two year follow-up per 1,000-person-years) | 55.6 (51.5, 60.0) | 50.6 (46.3, 55.1) | 51.3 (47.0, 56.1) | 58.6 (53.9, 63.8) | 69.5 (64.2, 75.1) | |

| Persons at Risk: | Person at Risk: | Person at Risk: | Person at Risk: | Person at Risk: | ||

| No UI at 1998 | No UI at 2000 | No UI at 2002 | No UI at 2004 | No UI at 2006 | ||

| N = 4,706 | N = 4,063 | N = 3,821 | N = 3,583 | N = 3,323 | ||

| Cumulative incidence rate of UI | 111 (103, 120) | 208 (197, 219) | 285 (273, 298) | 357 (343, 370) | 430 (417, 445) | |

| At each two year follow-up among every 1000 UI-free persons since 1998 | 2-year Cumulative incidence rate in 2000 since 1998 (N = 4,706) | 4-year Cumulative incidence rate in 2002 since 1998 (N = 4,063) | 6-year Cumulative incidence rate in 2004 since 1998 (N = 3,554) | 8-year Cumulative incidence rate in 2006 since 1998 (N = 3,131) | 10-year Cumulative incidence rate in 2008 since 1998 (N = 2,736) | |

| Cumulative incidence | 10.6% (9.8%, 11.5%) | 19.2% (18.2%, 20.2%) | 25.6% (24.4%, 26.7%) | 31.3% (30.1%, 32.5%) | 37.2% (36.0%, 38.5%) | |

| Age Category | ||||||

| CODA | 11.8% (9.9%, 13.8%) | 22.7% (20.3%, 25.3%) | 30.4% (27.7%, 33.2%) | 36.8% (34.0%, 39.7%) | 43.6% (40.7%, 46.6%) | |

| HRS | 10.0% (8.9%, 11.1%) | 18.2% (16.8%, 19.6%) | 24.6% (23.0%, 26.1%) | 30.2% (28.5%, 31.8%) | 36.4% (34.7%, 38.2%) | |

| War Babies | 11.1% (9.5%, 12.9%) | 18.5% (16.5%, 20.6%) | 23.8% (21.6%, 26.2%) | 29.3% (26.9%, 31.7%) | 33.9% (31.4%, 36.5%) | |

Prevalence of UI and 95% CI were estimated based on Binomial Distribution and the Exact 95% Confidence Limits of reported binomial proportion were reported.

Incidence rate and 95% confidence intervals were estimated based on modified Poisson regression

UI-urinary incontinence

CI-confidence interval

CODA- children of the depression (birth year 1924-1930)

HRS- original health and retirement survey (birth year 1931-1941)

War babies- (birth year 1942-1947)

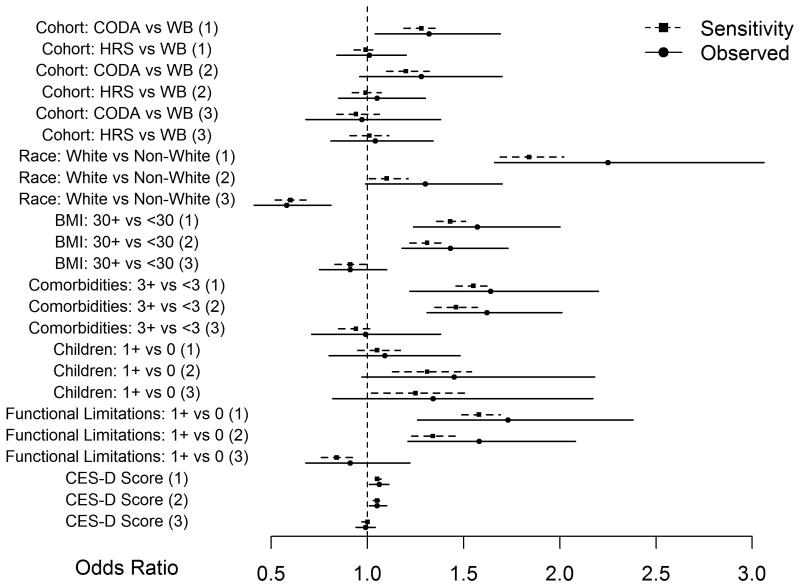

In the final multinomial logistic regression model, we found that obesity, older age, white race, functional limitations, more medical comorbidities, and greater depressive symptoms, but not parity at baseline were associated with increased odds of developing incident UI with persistence or fluctuation; these observed associations remained statistically significant in sensitivity analyses. (Figure 1) Older women, in the CODA birth cohort, had 1.3 increased odds (95%CI 1.0-1.7) of developing incident UI with persistence compared with the younger war babies birth cohort over 10 years. On sensitivity analysis, these associations remained statistically significant (2.5th to 97.5th percentile 1.2- 1.4). White women had 2.3 fold increased odds of developing incident UI with persistence compared with non-white women (95%CI 1.7- 3.1). On sensitivity analysis, this association also remained statistically significant (2.5th to 97.5th percentile 1.7-2.0). Compared with women without functional limitations at baseline, odds of developing incident UI with persistence increased by 73% among women with functional limitations (Adjusted OR 1.7, 95%CI 1.3-2.4). On sensitivity analysis, this association remained statistically significant (2.5th to 97.5th percentile 1.5-1.7). White race had 0.6 decreased odds of development of UI with fluctuation (95%CI 0.5-0.7) vs. development of UI with persistence. On sensitivity analysis, this association remained statistically significant (2.5th to 97.5th percentile 0.5-0.7). No other baseline risk factors demonstrated statistically significant associations for the development of UI with persistence vs. UI with fluctuation.

Figure 1.

Plot of observed OR (95% confidence interval) and 50th percentile (2.5th percentile, 97.5th percentile) of odds ratio from 10,000 sensitivity analyses.

Dotted line-50th percentile (2.5th percentile, 97.5th percentile) of odds ratio from 10,000 sensitivity analyses Solid line-observed odds ratio with 95% confidence interval from multinomial logistic regression OR-odds ratio; CI-confidence interval; CODA- children of the depression (birth year 1924-1930); HRS- original Health and Retirement Survey (birth year 1931-1941); WB-war babies- (birth year 1942-1947); UI-urinary incontinence; BMI-body mass index; CES-D- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Score

Discussion

In this large and well-established cohort of older women in the United States, we found that new onset urinary symptoms were common and variable. Among older women who did not report UI at baseline, roughly 21% developed UI with persistence and 21% developed UI with fluctuation over 10 years of follow-up.

Our findings of the high prevalence, incidence, fluctuation and persistence of urinary symptoms over a 10-year period add important epidemiologic insight to the natural history of UI in older women. Our findings for the prevalence of UI are somewhat lower than other studies.(8-10) This finding could be due to our starting with a select cohort of women who did not report UI symptoms at baseline. By excluding women with UI at baseline, we have good insight into women who develop of UI symptoms later in life.

The 2-year incidence rates of UI we observed are similar to those found in previous studies of urinary incidence over 2 years. A prospective analysis of women aged 54 to 79 years in the Nurses' Health Study I (NHS I) examining study responses to the 2000 and 2002 survey found a 2-year incidence of incontinence was 9.2%.(5) Komesu et al. examined the incidence of urgency UI between 2004 and 2006 among women aged ≥ 50 years in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), finding the incidence of new-onset urgency UI was 3.7%.(16)

We found that incident UI that develops later in life has strong associations with obesity, functional ability, and medical comorbidities, but not parity. This is consistent with the conclusions of Hunskaar et al. who observed that the association of UI with childbirth diminishes with age.(17) Interestingly, we found that development of UI in this older cohort of women tended to result in mixed UI and moderate to severe symptoms, rather than starting as either stress or urgency and evolving into mixed symptoms, or starting as mild UI and progressing in severity over time.

Our study has several limitations. This was a secondary analysis of a large population cohort. The primary objective of the HRS is to explore “changes in labor force participation and the health transitions that individuals undergo toward the end of their work lives”, not to examine urinary symptoms in older women. However this cohort is a well-characterized nationally-representative sample of older women with consistent follow-up of urinary symptoms over a 10-year period. We were also limited by missing data. In our multinomial logistic regression analysis of UI risk factors, we chose to categorize women as having “no UI”, “UI with fluctuation” and “UI with persistence” at 10 years after their initial screening; therefore, we were able to examine which baseline characteristics were associated with these different categories over a long follow-up. However, by categorizing women this way, we could not input UI symptom data for the 15% of women we could not clearly categorize. We were able to consider these uncategorized women in sensitivity analyses; results were similar to those in the primary analysis. We were also limited as we do not have information on treatment received by women with persistent and fluctuating symptoms which is an area for future research.

Conclusion

Development of UI in older women is common. Over ten-years, the cumulative incidence of UI in older women was 37.2% (95% CI 36.0%, 38.5%). In contrast to younger women who develop UI symptoms around the menopausal transition, we found that development of UI in this older cohort tended to result in mixed UI and moderate to severe symptoms. Finally, when we examined risk factors for development of UI in older women, later strong associations were observed with obesity, functional ability, and medical comorbidities, but not parity.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) Foundation. The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. Dr. Erekson is supported in part by The Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number KL2TR001088 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Sponsor's Role: none

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Dr. Elisabeth Erekson had full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. The authors for this work and their contributions to the research are as follows: Elisabeth A. Erekson, MD MPH: study design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content; Xiangyu Cong, PhD, MPH: study design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content; Mary K. Townsend, ScD: interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content Maria M. Ciarleglio, PhD: analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content.

References

- 1.Yip SO, Dick MA, McPencow AM, et al. The association between urinary and fecal incontinence and social isolation in older women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:146.e1–146.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melville JL, Delaney K, Newton K, et al. Incontinence severity and major depression in incontinent women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:585–592. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000173985.39533.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landefeld CS, Bowers BJ, Feld AD, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: Prevention of fecal and urinary incontinence in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:449–458. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, et al. and the Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trondelag. A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: The Norwegian EPINCONT study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trondelag J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lifford KL, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, et al. The epidemiology of urinary incontinence in older women: Incidence, progression, and remission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1191–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komesu YM, Rogers RG, Schrader RM, et al. Incidence and remission of urinary incontinence in a community-based population of women >/= 50 years. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0838-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townsend MK, Danforth KN, Lifford KL, et al. Incidence and remission of urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:167.e1–167.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waetjen LE, Liao S, Johnson WO, et al. Factors associated with prevalent and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: A longitudinal analysis of data: study of women's health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:309–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byles J, Millar CJ, Sibbritt DW, et al. Living with urinary incontinence: a longitudinal study of older women. Age Ageing. 2009;38:333–338. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahanlu D, Hunskaar S. The Hordaland Women's Cohort: prevalence, incidence, and remission of urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:1223–1229. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waetjen LE, Feng WY, Ye J, et al. Factors associated with worsening and improving urinary incontinence across the menopausal transition. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:667–677. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816386ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juster F, Suzman R. An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study. J Human Resources. 1995;30:s7–s56. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandvik H, Seim A, Vanvik A, et al. A severity index for epidemiological surveys of female urinary incontinence: Comparison with 48-hour pad-weighing tests. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:2<137::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report: Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study 2000 (Online) [Accessed November 6th, 201.]; Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-005.pdf.

- 15.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komesu Y, Schrader R, Rogers R, et al. Urgency Urinary Incontinence in Women >/= 50 years: Incidence, remission and predictors of change. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:17–23. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31820446e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunskaar S, Arnold EP, Burgio K, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2000;11:301–319. doi: 10.1007/s001920070021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erekson EA, Ciarleglio MM, Hanissian PD, et al. Functional disability and compromised mobility among older women with urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;21:170–175. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, et al. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1068–1074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manton KG. Demographic trends for the aging female population. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1997;52:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waetjen LE, Ye J, Feng WY, et al. Association between menopausal transition stages and developing urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:989–98. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bb531a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rortveit G, Hannestad YS, Daltveit AK, et al. Age- and type-dependent effects of parity on urinary incontinence: The Norwegian EPINCONT study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]