ABSTRACT

Nucleus is the residence and place of work for a plethora of long noncoding RNAs. Here, we provide a summary of the functions and functional mechanisms of several relatively well studied examples of nuclear long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the nucleus, such as Xist, NEAT1, MALAT1 and TERRA. The recently identified novel EIciRNA is also highlighted. These nuclear lncRNAs play a variety of roles with diverse molecular mechanisms in animal cells. We also discuss insights and concerns about current and future studies of nuclear lnc RNAs.

Keywords: EIciRNA, long noncoding RNA, nuclear, satellite RNA, transcription

Introduction

Eukaryotic transcripts can be either coding or noncoding based on the presence or absence of functional open reading frame. Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are divided arbitrarily into small (<200 nt) and long (>200 nt) ncRNAs (lncRNAs) based on their length. RNAs are transcribed from the nuclear genome in animal cells; the original place of essentially all RNAs is the nucleus, except the small fraction encoded by the mitochondrial DNA. Most ncRNAs small or long generally go through several steps of processing or biogenesis in the nucleus. For some ncRNAs, the final residence and functional place is the cytoplasm, where they may undergo further processing steps. For example, the ∼20 nt microRNAs are processed from nuclear primary microRNA transcripts with 2 steps of endoribonuclease cleavage, first in the nucleus and then in the cytoplasm. Actually, a lot of small ncRNAs are originated or processed from precursors or primary forms of lncRNAs. For small ncRNAs, they may reside and play roles either in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus. There are also reports about some small ncRNAs, such as microRNA-29b, getting back into the nucleus and may possess nuclear functions.1

There are a myriad of ncRNAs, especially lncRNAs, that remain and function solely in the nucleus. The long studied lncRNA Xist may be the founding member of the long regulatory ncRNAs, which by chance is also a nuclear lncRNA. The past decades have witnessed a dramatic increase in the inventory of nuclear lncRNAs. Diverse roles and multiple functional mechanisms have now been linked to lncRNAs in the nucleus.2-4 Our recent work has found a novel class of lncRNAs localizing in the nucleus and regulating transcription.5 In this minireview, we summarize the functions and functional mechanisms of some of the relatively well studied nuclear lncRNAs, and highlight our recent identification of EIciRNAs. Insights, current thinking and some concerns about nuclear roles of lncRNAs are discussed.

Xist and RoX

In mammals, a long ncRNA Xist is responsible for the inactivation of 1 X chromosome in female.6,7 The phenomenon of X chromosome inactivation in females was documented in 1949, and the central player Xist, a ∼17 knt (kilo-nucleotide) ncRNA in human was identified more than 4 decades later.8-10 Xist RNA is essential and responsible for the initiation, propagation, and maintenance of X chromosome inactivation via the recruiting of an array of epigenetic regulators. Xist is expressed from the future inactive X-chromosome. With the accumulation of the Xist RNA, it coats and spreads on the X-chromosome in cis. Xist directly interacts with SHARP, which recruits the co-repressor SMRT to regulate HDAC3, and eventually leads to the deacetylation of histones and some other epigenetic events to silence the transcription on the inactive X-chromosome.11-14 Xist RNA also recruits the polycomb repressive complex 1 and 2 (PRC1 and PRC2) to induce the PRC1 meditated mono-ubiquitylation of histone H2AK119 and the PRC2-dependent H3K37me3, respectively.15-22 A recent study shows that HnrnpK and Spen specifically interact with Xist. This interaction is not essential for the localization of Xist to the inactive X-chromosome but required for the silencing effect of Xist.23 A very interesting phenomenon is that the sequence and length of Xist are not conserved among different branches of mammals, although all mammalian Xist RNAs are composed of repeats of short units.24-28

In Drosophila melanogaster, compensation of X-chromosome dosage is fulfilled by transcriptional upregulation of the single X chromosome in male.28 Two lncRNAs roX1 and roX2, both transcribed from the X chromosome in male, are required for the X-chromosome activation by recruiting the Male-Specific Lethal (MSL) protein complex to increase histone H4 acetylation.29-37 RoX1 is ∼ 3.6 knt, and RoX2 is ∼1.1 knt in length. Both RoX1 and RoX2 paint the X chromosome via chromatin entry sites, and they are partially redundant in the X chromosome activation. Although both RoX1 and RoX2 are encoded by the X chromosome, their effects on X chromosome activation can be in trans, as RoX RNAs wrongly or artificially expressed from autosome lead to the same X chromosome activation in male.34,37

Xist and RoX RNAs are the first identified regulatory lncRNAs, and either by coincidence both regulate dosage compensation of X chromosome in animals. They also set up the concept that nuclear lncRNAs can be powerful master regulators of chromatin epigenetic status.

HOTAIR

For a long period, Xist and RoX RNAs were considered the only nuclear regulatory lncRNAs, until the milestone identification of lincRNA HOTAIR in 2007.38 LincRNA stands for long intergenic noncoding RNA, which is a class of lncRNAs transcribed in between genomic regions of coding genes. HOTAIR is transcribed from the intergenic region of HoxC gene loci and with a length of ∼2.2 knt.38 HOTAIR binds the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and the LSD1/CoREST/REST complex, and thus modulates histone modifications of target genes in trans to silence the transcription of HoxD loci.38-39 HOTAIR deletion actually results in a coordinated loss of PRC2 and LSD1 binding at hundreds of genes, and these genes also show a corresponding increase in their gene expression.40 Further studies show that HOTAIR can reprogram chromatin states during tumor metastasis.41-43 For example, in breast carcinomas, HOTAIR is upregulated with metastasis. Overexpression of HOTAIR in breast epithelial cells leads to the occupancy of PRC2 to over 800 additional genes, and the pattern of the PRC2 occupancy changes from that of the typical breast epithelial cells to that of embryonic fibroblasts.41-43

The identification of HOTAIR in combination with the development of RNA detection technologies such as microarray and second generation of nucleic acid sequencing has provided a surge in the search for lncRNAs and their functions and functional mechanisms in eukaryotic cell. A plethora of lncRNAs are now thought to utilize molecular mechanisms similar to HOTAIR, to recruit key epigenetic factors for either cis or trans epigenetic regulation of chromatin status in the nucleus.44-47

Neat1 and Malat1

In a search for nuclear enriched abundant transcript (NEAT) RNAs, 2 lncRNAs NEAT1 and NEAT2 (already identified as MALAT-1 in previous studies) are discovered.48 NEAT1 is widely expressed in all sorts of mammalian cells, and is transcribed by RNA polymerase II (pol II). NEAT1 exists in 2 forms: a ∼3.7 knt isoform of NEAT1_1 with poly (A) tail and a ∼23 knt isoform of NEAT1_2.49,50 Both isoforms of NEAT1 are localized in and also key components of the paraspeckles.50-53 Paraspeckles are unique subnuclear structures composed of specific proteins and RNAs. Some of these specific proteins belong to the Drosophila Behavior/Human Splicing (DBHS) family such as PSPC1, SFPQ (PSF) and NONO (p54nrb).54,55 NEAT1_2 has been shown to directly interact with the SFPQ and NONO to form a pivotal component for paraspeckle formation, and NEAT1_2 knockdown disturbs the paraspeckle formation.50 NEAT1_1 can bind to PSPC1, which is also localized in paraspeckles. NEAT1_1 overexpression can increase the number of paraspeckles, although NEAT1_1 deletion does not block the formation of paraspeckles.49 A to I edited mRNAs are retained within the nucleus inside paraspeckle in NEAT1-dependent manner.51 Hyper-edited RNAs with inverted repeat sequences in the 3′ UTR are retained in paraspeckles of differentiated cells.48,56-58 Upon NEAT1 deletion, paraspeckles are not formed and the RNAs with inverted repeats are transported into cytoplasm.48,56-58 Recently, lines of evidence show that NEAT1 has important roles in the formation of corpus luteum and mammary gland as suggested by the phenotypes of NEAT1 knockout mice.59,60 However, critical roles of NEAT1 and paraspeckles in mammalian cells require further investigations.

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1), also known as NEAT2 is a lncRNA about 8 knt, and is highly conserved in mammalian species.48,61-64 MALAT1 was initially identified as a prognostic parameter for lung cancer patients, and is also one of the first ncRNAs to be associated with a disease.61,64 High expression level of MALAT1 is detected in many human carcinomas, and level of MALAT1 in early-stage tumors is a prognostic marker for patient survival.65-69

MALAT1 is transcribed by pol II. The region of about one hundred nucleotides at the 3′ end of unprocessed MALAT1 is the most evolutionarily conserved part of this transcript from fish to human, and this 3′ end has the cloverleaf secondary structure of tRNAs.63,71 Just like tRNAs, processing of the MALAT1 3′ end is executed by RNase P and RNase Z.63,71 NEAT1_2 is also processed like MALAT1 by cleavage with RNase P at its 3' end by recognizing a tRNA-like structure, and the mature 3' end of both lncRNAs are protected by triple helical structures.70,71

MALAT1 is a component of nuclear speckles (also known as SC35 splicing domains), and it contains 2 regions responsible for protein interaction and RNA binding for its localization.48,62,73 Nuclear speckles are involved in mRNA processing, splicing, and export of mRNA, and MALAT1 is thought to serve as a scaffold for the pre-mRNA processing complex in nuclear speckles.48,73 siRNA meditated knockdown of the speckle protein RNPS1, SRm160, or IBP160 results in disrupted MALAT1 localization.72 MALAT1 localization in nuclear speckles is also thought to participate in active transcription.74 Blocking pol II transcription with α-amanitin or 5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribobenzimidazole results in MALAT1 diffusing in the nucleus.75 MALAT1 is also reported to interact with pre-mRNA splicing factors such as SR proteins,62,75-77 although deleting MALAT1 does not incur splicing change in lung cancer cells.64,78,79

MALAT1 binds to unmethylated polycomb2 (Pc2) to regulate the nuclear localization of Pc2 based on several researches.77,80 Pc2 is a component of the PRC1, and its methylation/demethylation cycle controls the expression of multiple growth-signal responsive genes. Unmethylated Pc2 relocates from polycomb bodies to nuclear speckles by binding to MALAT1, and this binding further promotes the SUMOylation of a critical transcription factor E2F1, which activates a growth-control gene program.77,80 In neurons MALAT1 has also been shown to interact with the TAR DNA binding protein (Tdp-43) and to regulate synapse formation.81 TDP-43 is a nuclear protein that regulates transcription, alternative splicing, and RNA stability.82-84

MALAT1 may have diverse functions in multiple cellular events. However, in instances of MALAT1 deletion, no significant effect on nuclear speckles is observed, and there is no distinct phenotype in the MALAT1 knockout mice.85-87 It seems that despite all lines of evidence indicating critical functions of MALAT1 in cell cultures, its actual relevance in animal physiology remains unknown.

Some other nuclear lncRNAs

The lncRNA H19 has been known for more than two decades.88,89 In recent years H19 has been identified as the primary transcript of miR-675.90,91 On the other hand, H19 may also possess a cytoplasmic role as sponge of let-7 and miR-106a.92,93 It seems that H19 as one of the most abundant, conserved, and first identified lncRNAs in mammals remains intriguing for its actual physiological functions and functional mechanism. Another nuclear lncRNA Pnky is found in mammalian neural stem cells, and it interacts with PTBP1 to regulate the expression and alternative splicing of some genes.94

Another class of RNAs are derived from the enhancers of an array of genes, and are known as enhancer RNAs (eRNAs).95 eRNAs are a large species of lncRNAs residing in the nucleus and maybe never apart from the chromatin. Enchancer DNA elements can regulate the transcription of genes in cis from a distal intragenic or intergenic region.96-101 Transcription at enhancer can produce bi-directional and uni-directional eRNAs,102,103 and the main function as well as the reason of producing 2 forms of eRNAs is still unclear. eRNAs normally are recognized as non-polyadenylated single exon, although spliced and polyadenylated eRNAs have also been shown to exist.103-105 eRNAs are positively regulated by Androgen, estradiol, P53, MYOD, and MYOG in various conditions.106-108 Under the estradiol treatment, eRNAs from the enhancers of the estradiol induced genes are increased in MCF7 cells.102 Similarly, Nutlin-3 induces eRNA production from the enhancer of p53-dependent genes.107 The REV-ERB signaling can negatively regulate the generation of eRNAs through binding to the enhancer of target genes.109 The exact mechanism of eRNAs in regulating gene transcription is largely unknown. It has also been shown that eRNAs can stabilize the looping of the cohesion and/or Mediator complex interacting with the enhancer of the target genes, although eRNA deletion does not always influence the loop formation.102,110

Some housekeeping lncRNAs also reside in the nucleus, and these include centromeric satellite RNAs and telomere RNAs, and both actually possess regulatory roles along their canonical functions. Centromere is composed of satellite and retroelement repetitive DNA sequences in most eukaryotes.111-114 RNAs transcribed by pol II from the repetitive DNA elements are termed centromeric satellite RNAs. Centromeric satellite RNAs usually are in a length of 35–5000 nt,115-118 and they have a key role on centromere/kinetochore assembling and function in many organisms.119-121 The minor satellite RNA in mice even plays a role in trans to regulate the activity of telomerase in embryonic stem cells.122 Telomere RNA is transcribed by pol II from telomeric ends of the chromosome. The length of telomere RNA varies from 100 to 9000 nt and contains various number of UUAGGG repeat sequences in different eukaryotic organisms, and thus it is known as telomeric repeat-contain RNA (TERRA).123 TERRA is a key component of telomere, which is a nucleoprotein structure that protects the termini of the chromosome from damage and degradation, and maintains the chromosome length, integrity, and stability.124-127

EIciRNAs

In the past years, circular RNAs (circRNAs) have emerged as a large family of ncRNAs.128-132 In canonical or linear splicing, the 5′ end of the exon joins the 3′ end of another exon upstream (more 5′ in the linear precursor RNA). The circRNAs are generated from coding (sometimes also noncoding) regions of genes by a process called back-splicing, in which the 5′ end of an exon joins with the 3′ end of itself or another exon downstream (more 3′ in the linear precursor RNA).

Thousands of circRNAs have been identified in eukaryotic cells. Most circRNAs are composed exclusively of exonic sequences, without association with polyribosomes, and localized in the cytoplasm with cell specificity.128,129,133,134 Two of these circRNAs have been shown to function as microRNA sponge in the cytoplasm.128,129 Recently, we have identified a new subclass of circRNAs, which are circularized with introns “retained” between the circularized exons, and for this reason we call them exon-intron circRNAs (EIciRNAs).5 The identification of circRNAs and EIciRNAs actually makes us rethink the meaning of “coding” sequences of the “coding” genes, as now both mRNAs and lncRNAs can be generated from the same exonic sequences of pre-mRNA. In contrast to the other circRNAs, EIciRNAs are localized exclusively in the nucleus. Further investigations reveal that EIciRNAs associate with pol II and enhance the initiation of transcription in cis by promoting pol II binding at the core promoter of the EIciRNA parent genes.5 The association between EIciRNAs and pol II is mediated by U1 snRNP via the RNA-RNA binding of U1 snRNA and the EIciRNAs. The 5′ splicing site of the retained intron in EIciRNAs is the actual binding site of U1 snRNA. Thus, EIciRNAs are a new class of nuclear lncRNAs with functions in transcriptional regulation through RNA-RNA interaction.

A series of unknowns are associated with EIciRNAs. We have shown in 2 examples that EIciRNAs serve as a positive feedback to promote transcription, and it remains to be examined whether this is true for all EIciRNAs to their parent genes genome-wide. It is also possible that EIciRNAs have a link with epigenetic chromatin status of active transcription. EIciRNAs has colocalization with their parent genomic loci, although they are also distributed to multiple nuclear regions. The close association of EIciRNAs with U1 snRNA indicates strongly that EIciRNAs may be localized to nuclear speckles, where active transcription and splicing can be coordinated. We speculate that besides their cis role as individuals, EIciRNAs as a whole could possess a trans role synergistically by keeping factors such as U1 snRNP at the nuclear sites of active gene expression.

Perspective

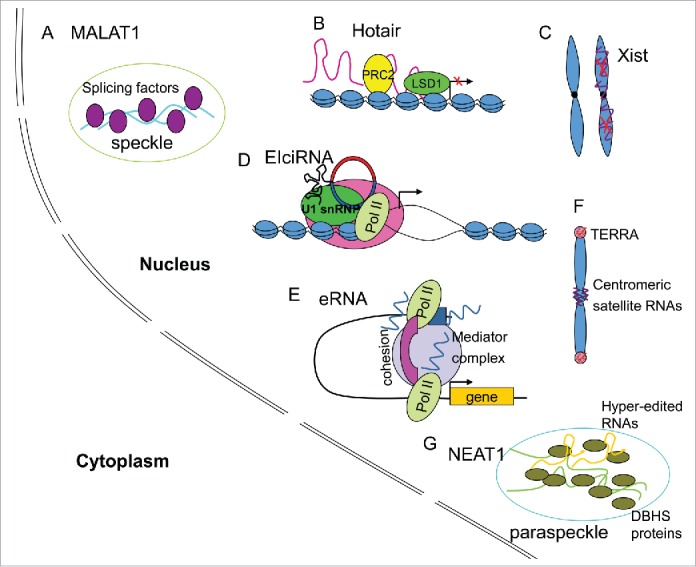

LncRNAs are recognized as important regulators in different aspects of cellular events. In this review, we have summarized a number of lncRNAs that are retained and function in the nucleus (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Functional mechanisms of some nuclear lncRNAs. (A) MALAT1 localizes in the nuclear speckles and interacts with splicing factors to regulate splicing. (B) HOTAIR interacts with critical epigenetic regulators to regulate the chromatin status. (C) Xist RNA silences 1 X chromosome in female via epigenetic regulation. (D) EIciRNAs enhance the initiation of pol II transcription of their parent genes by interacting with U1 snRNP. (E) eRNAs promote transcription in cis by enhancing chromatin looping. (F) Centromeric satellite RNAs play roles in centromere/kinetochore formation and function, while TERRA plays roles in the telomeres. (G) NEAT1 localizes and functions in paraspeckles.

Localization of ncRNAs must be regulated to coordinate the whole process of biogenesis and the function. The existence of some lncRNAs predominantly or exclusively in the nucleus requires the involvement of localization mechanisms either active or passive. One would speculate that the association of lncRNAs such as Xist, HOTAIR, and eRNAs with chromatin keeps them in the nucleus. On the other hand the binding of nuclear proteins to lncRNAs such as MALAT1, NEAT1, and EIciRNAs ensures the nuclear localization of these RNAs. Nuclear ncRNAs may also lack sequences or features required for active nuclear exportation. Is it possible that some lncRNAs may shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm? At least there is no such an example so far.

The abundance of each nuclear lncRNA has to be regulated to ensure proper functionality and localization. Theoretically, cis effect requires only lower abundance, while higher abundance for trans effect. The relative abundance is supposedly decided by the production rate (transcription and biogenesis) and the process of degradation. For most nuclear lncRNAs, we still know little about the dynamic regulation in their transcription, biogenesis, and degradation.

Nuclear lncRNAs play quite diverse roles with multiple molecular mechanisms. A substantial number of nuclear lncRNAs are conserved in mammals, indicating further functional significance. The physiological roles of most nuclear lncRNAs are still elusive, even for those with known functional mechanisms, such as NEAT1, MALAT1, and EIciRNAs. One of the reasons for missing physiological relevance may be because of the fact that research about lncRNAs in model organisms such as C. elegans, Drosophila, zebra fish, and mice are still limited. The many unknowns about nuclear lncRNAs urge substantially more investigations in this field.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Liang Chen and other members of the Ge Shan lab for discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB943000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (91519333 and 31471225), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WK2070000034).

References

- [1].Hwang HW, Wentzel EA, Mendell JT. A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science 2007; 315:97-100; PMID:17204650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1136235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hu S, Wu J, Chen L, Shan G. Signals from noncoding RNAs:unconventional roles for conventional pol III transcripts. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012; 44(11):1847-51; PMID:22819850; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ip JY, Nakagawa S. Long non-coding RNAs in nuclear bodies. Dev Growth Differ 2012; 54(1):44-54; PMID:22070123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. Non-coding RNAs: key regulators of mammalian transcription. Trends Biochem Sci 2012; 37(4):144-51; PMID:22300815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li Z, Huang C, Bao C, Chen L, Lin M, Wang X, Zhong G, Yu B, Hu W, Dai L, et al. “Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus” Nat Struct Mol Biol 2015; 22(3):256-64; PMID:25664725; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Marin I, Siegal ML, Baker BS. The evolution of dosage-compensation mechanisms. Bioessays 2000; 22:1106-14; PMID:11084626; http://dx.doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wutz A. RNAs templating chromatin structure for dosage compensation in animals. Bioessays 2003; 25(5):434-42; PMID:12717814; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.10274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Borsani G, Tonlorenzi R, Simmler MC, Dandolo L, Arnaud D, Capra V, Grompe M, Pizzuti A, Muzny D, Lawrence C, et al.. Characterization of a murine gene expressed from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 1991; 351:325-29; PMID:2034278; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/351325a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brown CJ, Hendrich BD, Rupert JL, Lafreniere RG, Xing Y, Lawrence J, Willard HF. The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell 1992; 71:527-42; PMID:1423611; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90520-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brockdorff N, Ashworth A, Kay GF, McCabe VM, Norris DP, Cooper PJ, Swift S, Rastan S. The product of the mouse Xist gene is a 15 kb inactive X-specific transcript containing no conserved ORF and located in the nucleus. Cell 1992; 71:515-26; PMID:1423610; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90519-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].van Bemmel JG, Mira-Bontenbal H, Gribnau J. Cis- and trans-regulation in X inactivation. Chromosoma 2016; 125(1):41-50; PMID:26198462; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00412-015-0525-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chaumeil J, Le Baccon P, Wutz A, Heard E. A novel role for Xist RNA in the formation of a repressive nuclear compartment into which genes are recruited when silenced. Genes Dev 2006; 20:2223-37; PMID:16912274; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.380906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chu C, Zhang QC, da Rocha ST, Flynn RA, Bharadwaj M, Calabrese JM, Magnuson T, Heard E, Chang HY. Systematic discovery of xist RNA binding proteins. Cell 2015; 161:404-16; PMID:25843628; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McHugh CA, Chen CK, Chow A, Surka CF, Tran C, McDonel P, Pandya-Jones A, Blanco M, Burghard C, Moradian A, et al.. The Xist lncRNA interacts directly with SHARP to silence transcription through HDAC3. Nature 2015; 521:232-6; PMID:25915022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sun BK, Deaton AM, Lee JT. A transient heterochromatic state in Xist preempts X inactivation choice without RNA stabilization. Mol Cell 2006; 21:617-28; PMID:16507360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ, Lee JT. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science 2008; 322:750-6; PMID:18974356; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1163045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb group silencing. Science 2002; 298:1039-43; PMID:12351676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1076997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Czermin B, Melfi R, McCabe D, Seitz V, Imhof A, Pirrotta V. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 2002; 111:185-96; PMID:12408863; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00975-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kuzmichev A, Nishioka K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev 2002; 16:2893-905; PMID:12435631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1035902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].de Napoles M, Mermoud JE, Wakao R, Tang YA, Endoh M, Appanah R, Nesterova TB, Silva J, Otte AP, Vidal M, et al.. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation. Dev Cell 2004; 7:663-76; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fang J, Chen T, Chadwick B, Li E, Zhang Y. Ring1b-mediated H2A ubiquitination associates with inactive X chromosomes and is involved in initiation of X inactivation. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:52812-5; PMID:15509584; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.C400493200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Plath K, Talbot D, Hamer KM, Otte AP, Yang TP, Jaenisch R, Panning B. Developmentally regulated alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 1 proteins on the inactive X chromosome. J Cell Biol 2004; 167:1025-35; PMID:15596546; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200409026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chu C, Zhang QC, da Rocha ST, Flynn RA, Bharadwaj M, Calabrese JM, Magnuson T, Heard E, Chang HY. Systematic discovery of xist RNA binding proteins. Cell 2015; 161:404-16; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hoki Y, Kimura N, Kanbayashi M, Amakawa Y, Ohhata T, Sasaki H, Sado T. A proximal conserved repeat in the Xist gene is essential as a genomic element for X-inactivation in mouse. Development 2009; 136(1):139-46; PMID:19036803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.026427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lyon MF. X-chromosome inactivation:a repeat hypothesis. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1998; 80(1-4):133-7; PMID:9678347; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000014969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Duszczyk MM, Wutz A, Rybin V, Sattler M. The Xist RNA A-repeat comprises a novel AUCG tetraloop fold and a platform for multimerization. RNA 2011; 17(11):1973-82; PMID:21947263; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.2747411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hoki Y, Kimura N, Kanbayashi M, Amakawa Y, Ohhata T, Sasaki H, Sado T. A proximal conserved repeat in the Xist gene is essential as a genomic element for X-inactivation in mouse. Development 2009; 136(1):139-46; PMID:19036803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.026427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Duszczyk MM, Zanier K, Sattler M. A NMR strategy to unambiguously distinguish nucleic acid hairpin and duplex conformations applied to a Xist RNA A-repeat. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36(22):7068-77; PMID:18987004; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkn776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Marin I, Siegal ML, Baker BS. The evolution of dosage-compensation mechanisms. Bioessays 2000; 22:1106-14; PMID:11084626; http://dx.doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Amrein H, Axel R. Genes expressed in neurons of adult male Drosophila. Cell 1997; 88:459-69; PMID:9038337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81886-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Meller VH, Wu KH, Roman G, Kuroda MI, Davis RL. roX1 RNA paints the X chromosome of male Drosophila and is regulated by the dosage compensation system. Cell 1997; 88:445-57; PMID:9038336; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81885-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Meller VH, Rattner BP. The roX genes encode redundant male-specific lethal transcripts required for targeting of the MSL complex. EMBO J 2002; 21:1084-91; PMID:11867536; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kageyama Y, Mengus G, Gilfillan G, Kennedy HG, Stuckenholz C, Kelley RL, Becker PB, Kuroda MI. Association and spreading of the Drosophila dosage compensation complex from a discrete roX1 chromatin entry site. EMBO J 2001; 20:2236-45; PMID:11331589; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Henry RA, Tews B, Li X, Scott MJ. Recruitment of the male-specific lethal (MSL) dosage compensation complex to an autosomally integrated roX chromatin entry site correlates with an increased expression of an adjacent reporter gene in male Drosophila. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:31953-8; PMID:11402038; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M103008200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bashaw GJ, Baker BS. The msl-2 dosage compensation gene of Drosophila encodes a putative DNA-binding protein whose expression is sex specifically regulated by Sex-lethal. Development 1995; 121:3245-58; PMID:7588059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Franke A, Baker BS. The rox1 and rox2 RNAs are essential components of the compensasome, which mediates dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell 1999; 4:117-22; PMID:10445033; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80193-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kelley RL, Meller VH, Gordadze PR, Roman G, Davis RL, Kuroda MI. Epigenetic spreading of the Drosophila dosage compensation complex from roX RNA genes into flanking chromatin. Cell 1999; 98(4):513-22; PMID:10481915; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81979-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et al.. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell 2007; 129:1311-23; PMID:17604720; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, Shi Y, Segal E, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science 2010; 329(5992):689-93; PMID:20616235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1192002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schorderet P, Duboule D. Structural and functional differences in the long non-coding RNA hotair in mouse and human. PLoS Genet 2011. May; 7(5):e1002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al.. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 2010; 464:1071-6; PMID:20393566; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kogo R, Shimamura T, Mimori K, Kawahara K, Imoto S, Sudo T, Tanaka F, Shibata K, Suzuki A, Komune S, et al.. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR regulates Polycomb-dependent chromatin modification and is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancers. Cancer Res 2011; 71:6320-6; PMID:21862635; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. Non-coding RNAs:key regulators of mammalian transcription. Trends Biochem Sci 2012; 37(4):144-51; PMID:22300815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bhan A, Mandal SS. LncRNA HOTAIR: A master regulator of chromatin dynamics and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1856(1):151-64; PMID:26208723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hajjari M, Salavaty A. HOTAIR: an oncogenic long non-coding RNA in different cancers. Cancer Biol Med 2015; 12(1):1-9; PMID:25859406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhou X, Chen J, Tang W. The molecular mechanism of HOTAIR in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and drug resistance. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2014; 46(12):1011-5; PMID:25385164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/abbs/gmu104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wu Y, Zhang L, Wang Y, Li H, Ren X, Wei F, Yu W, Wang X, Zhang L, Yu J, et al.. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR involvement in cancer. Tumour Biol 2014; 35(10):9531-8; PMID:25168368; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s13277-014-2523-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hutchinson JN, Ensminger AW, Clemson CM, Lynch CR, Lawrence JB, Chess A. A screen for nuclear transcripts identifies two linked noncoding RNAs associated with SC35 splicing domains. BMC Genomics 2007; 8:39; PMID:17270048; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-8-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Guru SC, Agarwal SK, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Crabtree JS, Weisemann JM, Kester MB, Kim YS, Wang Y, Emmert-Buck MR, et al.. A transcript map for the 2.8-Mb region containing the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 locus. Genome Res 1997; 7:725-35; PMID:9253601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sasaki YT, Ideue T, Sano M, Mituyama T, Hirose T. MENepsilon / β noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci U S A 2009; 106:2525-30; PMID:19188602; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0807899106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chen LL, Carmichael GG. Altered nuclear retention of mRNAs containing inverted repeats in human embryonic stem cells: functional role of a nuclear noncoding RNA. Mol Cell 2009; 35:467-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, Lawrence JB. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell 2009; 33:717-26; PMID:19217333; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sunwoo H, Dinger ME, Wilusz JE, Amaral PP, Mattick JS, Spector DL. MEN epsilon / β nuclearretained non-coding RNAs are up-regulated upon muscle differentiation and are essential components of paraspeckles. Genome Res 2009; 19:347-59; PMID:19106332; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.087775.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fox AH, Lam YW, Leung AK, Lyon CE, Andersen J, Mann M, Lamond AI. Paraspeckles: a novel nuclear domain. Curr Biol 2002; 12:13-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Fox AH1, Bond CS, Lamond AI. P54nrb forms a heterodimer with PSP1 that localizes to paraspeckles in an RNA-dependent manner. Mol Biol Cell 2005; 16:5304-15; PMID:16148043; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ip JY, Nakagawa S. Long non-coding RNAs in nuclear bodies. Dev Growth Differ 2012; 54(1):44-54; PMID:22070123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Chen LL, DeCerbo JN, Carmichael GG. Alu element- mediated gene silencing. EMBO J 2008; 27:1694-705; PMID:18497743; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2008.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Faulkner GJ, Kimura Y, Daub CO, Wani S, Plessy C, Irvine KM, Schroder K, Cloonan N, Steptoe AL, Lassmann T, et al.. The regulated retrotransposon transcriptome of mammalian cells. Nat Genet 2009; 41:563-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Nakagawa S, Shimada M, Yanaka K, Mito M, Arai T, Takahashi E, Fujita Y, Fujimori T, Standaert L, Marine JC, et al.. The lncRNA Neat1 is required for corpus luteum formation and the establishment of pregnancy in a subpopulation of mice. Development 2014; 141(23):4618-27; PMID:25359727; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.110544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Standaert L, Adriaens C, Radaelli E, Van Keymeulen A, Blanpain C, Hirose T, Nakagawa S, Marine JC. The long noncoding RNA Neat1 is required for mammary gland development and lactation. RNA 2014; 20(12):1844-9; PMID:25316907; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.047332.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Boing S, Metzger R, Schneider PM, Tidow N, Brandt B, Buerger H, Bulk E, et al.. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin beta4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2003; 22:8031-41; PMID:12970751; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, Song DY, Pan Q, Watt AT, Freier SM, Bennett CF, Sharma A, Bubulya PA, et al.. The nuclearretained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol Cell 2010; 39:925-38; PMID:20797886; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wilusz JE, Freier SM, Spector DL. 3′end processing of a long nuclear-retained noncoding RNA yields a tRNA-like cytoplasmic RNA. Cell 2008; 135:919-32; PMID:19041754; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Diederichs S. MALAT1 — a paradigm for long noncoding RNA function in cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013; 91(7):791-801; PMID:23529762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00109-013-1028-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Luo JH, Ren B, Keryanov S, Tseng GC, Rao UN, Monga SP, Strom S, Demetris AJ, Nalesnik M, Yu YP, et al.. Transcriptomic and genomic analysis of human hepatocellular carcinomas and hepatoblastomas. Hepatology 2006; 44:1012-24; PMID:17006932; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/hep.21328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lin R, Maeda S, Liu C, Karin M, Edgington TS. A large noncoding RNA is amarker formurine hepatocellular carcinomas and a spectrum of human carcinomas. Oncogene 2007; 26:851-8; PMID:16878148; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1209846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Guffanti A, Iacono M, Pelucchi P, Kim N, Soldà G, Croft LJ, Taft RJ, Rizzi E, Askarian-Amiri M, Bonnal RJ, et al.. A transcriptional sketch of a primary human breast cancer by 454 deep sequencing. BMC Genomics 2009; 10:163; PMID:19379481; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-10-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lai MC, Yang Z, Zhou L, Zhu QQ, Xie HY, Zhang F, Wu LM, Chen LM, Zheng SS. Long non-coding RNA MALAT-1 overexpression predicts tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Med Oncol 2011; 29:1810-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Schmidt LH, Spieker T, Koschmieder S, Schäffers S, Humberg J, Jungen D, Bulk E, Hascher A, Wittmer D, Marra A, et al.. The long noncoding MALAT-1 RNA indicates a poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer and induces migration and tumor growth. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6:1984-92; PMID:22088988; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182307eac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wilusz JE, Jnbaptiste CK, Lu LY, Kuhn CD, Joshua-Tor L, Sharp PA. A triple helix stabilizes the 3′ ends of long noncoding RNAs that lack poly(A) tails. Genes Dev 2012; 26:2392-407; PMID:23073843; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.204438.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Brown JA, Valenstein ML, Yario TA, Tycowski KT, Steitz JA. Formation of triple-helical structures by the 3′-end sequences of MALAT1 and MENbeta noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:19202-7; PMID:23129630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1217338109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Miyagawa R, Tano K, Mizuno R, Nakamura Y, Ijiri K, Rakwal R, Shibato J, Masuo Y, Mayeda A, Hirose T, et al.. Identification of cis- and trans-acting factors involved in the localization of MALAT-1 noncoding RNA to nuclear speckles. RNA 2012; 18:738-51; PMID:22355166; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.028639.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Spector DL, Lamond AI. Nuclear speckles. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 1; 3(2):a000646; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a000646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Bernard D, Prasanth KV, Tripathi V, Colasse S, Nakamura T, Xuan Z, Zhang MQ, Sedel F, Jourdren L, Coulpier F, et al.. A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. EMBO J 2010; 29:3082-93; PMID:20729808; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2010.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Anko ML, Muller-McNicoll M, Brandl H, Curk T, Gorup C, Henry I, Ule J, Neugebauer KM. The RNA-binding landscapes of two SR proteins reveal unique functions and binding to diverse RNA classes. Genome Biol 2012; 13:R17; PMID:22436691; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-r17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sanford JR, Wang X, Mort M, Vanduyn N, Cooper DN, Mooney SD, Edenberg HJ, Liu Y. Splicing factor SFRS1 recognizes a functionally diverse landscape of RNA transcripts. Genome Res 2009; 19:381-94; PMID:19116412; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.082503.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Yang L, Lin C, Liu W, Zhang J, Ohgi KA, Grinstein JD, Dorrestein PC, Rosenfeld MG. ncRNA- and Pc2 methylation dependent gene relocation between nuclear structures mediates gene activation programs. Cell 2011; 147:773-88; PMID:22078878; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Bourgeois CF, Lejeune F, Stevenin J. Broad specificity of SR (serine/arginine) proteins in the regulation of alternative splicing of pre-messenger RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2004; 78:37-88; PMID:15210328; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)78002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Long JC, Caceres JF. The SR protein family of splicing factors:master regulators of gene expression. Biochem J 2009; 417:15-27; PMID:19061484; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BJ20081501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bernstein E, Duncan EM, Masui O, Gil J, Heard E, Allis CD. Mouse polycomb proteins bind differentially to methylated histone H3 and RNA and are enriched in facultative heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:2560-9; PMID:16537902; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2560-2569.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, Ling SC, Sun E, Wancewicz E, Mazur C, et al.. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14:459-68; PMID:21358643; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.2779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Buratti E, Baralle FE. Multiple roles of TDP-43 in gene expression, splicing regulation, and human disease. Front Biosci 2008; 13:867-78; PMID:17981595; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kuo PH, Doudeva LG, Wang YT, Shen CK, Yuan HS. Structural insights into TDP-43 in nucleic-acid binding and domain interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:1799-808; PMID:19174564; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkp013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, Konig J, Hortobagyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, et al.. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14:452-8; PMID:21358640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Nakagawa S, Ip JY, Shioi G, Tripathi V, Zong X, Hirose T, Prasanth KV. Malat1 is not an essential component of nuclear speckles in mice. RNA 2012; 18:1487-99; PMID:22718948; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.033217.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Zhang B, Arun G, Mao YS, Lazar Z, Hung G, Bhattacharjee G, Xiao X, Booth CJ, Wu J, Zhang C, et al.. The lncRNA Malat1 is dispensable for mouse development but its transcription plays a cis-regulatory role in the adult. Cell Rep 2012; 2:111-23; PMID:22840402; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, Lawrence JB. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell 2009; 33:717-26; PMID:19217333; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Pachnis V, Belayew A, Tilghman SM. Locus unlinked to α-fetoprotein under the control of the murine raf and Rif genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1984; 81(17):5523-7; PMID:6206499; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Brannan CI, Dees EC, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10(1):28-36; PMID:1688465; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.10.1.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Cai X, Cullen BR. The imprinted H19 noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. RNA 2007; 13(3):313-6; PMID:17237358; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.351707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Keniry A, Oxley D, Monnier P, Kyba M, Dandolo L, Smits G, Reik W. The H19 lincRNA is a developmental reservoir of miR-675 that suppresses growth and Igf1r. Nat Cell Biol 2012; 14(7):659-65; PMID:22684254; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Kallen AN, Zhou XB, Xu J, Qiao C, Ma J, Yan L, Lu L, Liu C, Yi JS, Zhang H, et al.. The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Mol Cell 2013; 52(1):101-12; PMID:24055342; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Imig J, Brunschweiger A, Brümmer A, Guennewig B, Mittal N, Kishore S, Tsikrika P, Gerber AP, Zavolan M, Hall J. miR-CLIP capture of a miRNA targetome uncovers a lincRNA H19-miR-106a interaction. Nat Chem Biol 2015; 11(2):107-14; PMID:25531890; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nchembio.1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ramos AD, Andersen RE, Liu SJ, Nowakowski TJ, Hong SJ, Gertz CC, Salinas RD, Zarabi H, Kriegstein AR, Lim DA. The long noncoding RNA Pnky regulates neuronal differentiation of embryonic and postnatal neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2015; 16(4):439-47; PMID:25800779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, et al.. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature 2010; 465 (7295):182-7; PMID:20393465; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature09033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Barish GD, Yu RT, Karunasiri M, Ocampo CB, Dixon J, Benner C, Dent AL, Tangirala RK. Evans RM: Bcl-6 and NF-kappaB cistromes mediate opposing regulation of the innate immune response. Genes Dev 2010; 24:2760-5; PMID:21106671; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1998010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger TR, Eeckhoute J, Brodsky AS, Keeton EK, Fertuck KC, Hall GF, et al.. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet 2006; 38:1289-97; PMID:17013392; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 2010; 38:576-89; PMID:20513432; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].John S, Sabo PJ, Thurman RE, Sung MH, Biddie SC, Johnson TA, Hager GL, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat Genet 2011; 43:264-8; PMID:21258342; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Lefterova MI, Steger DJ, Zhuo D, Qatanani M, Mullican SE, Tuteja G, Manduchi E, Grant GR, Lazar MA. Cell-specific determinants of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma function in adipocytes and macrophages. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30:2078-89; PMID:20176806; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01651-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Nielsen R, Pedersen TA, Hagenbeek D, Moulos P, Siersbaek R, Megens E, Denissov S, Borgesen M, Francoijs KJ, Mandrup S, et al.. Genome-wide profiling of PPARgamma:RXR and RNA polymerase II occupancy reveals temporal activation of distinct metabolic pathways and changes in RXR dimer composition during adipogenesis. Genes Dev 2008; 22:2953-67; PMID:18981474; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.501108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Li W, Notani D, Ma Q, Tanasa B, Nunez E, Chen AY, Merkurjev D, Zhang J, Ohgi K, Song X, et al.. Functional roles of enhancer RNAs for oestrogen-dependent transcriptional activation. Nature 2013; 498:516-20; PMID:23728302; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature12210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].De Santa F, Barozzi I, Mietton F, Ghisletti S, Polletti S, Tusi BK, Muller H, Ragoussis J, Wei CL, Natoli G. A large fraction of extragenic RNA Pol II transcription sites overlap enhancers. PLoS Biol 2010; 8:e1000384; PMID:20485488; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, et al.. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature 2010; 465:182-7; PMID:20393465; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature09033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Koch F, Fenouil R, Gut M, Cauchy P, Albert TK, Zacarias-Cabeza J, Spicuglia S, de la Chapelle AL, Heidemann M, Hintermair C, et al.. Transcription initiation platforms and GTF recruitment at tissue-specific enhancers and promoters. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011; 18:956-63; PMID:21765417; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Wang D, Garcia-Bassets I, Benner C, Li W, Su X, Zhou Y, Qiu J, Liu W, Kaikkonen MU, Ohgi KA, et al.. Reprogramming transcription by distinct classes of enhancers functionally defined by eRNA. Nature 2011; 474:390-4; PMID:21572438; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Melo CA, Drost J, Wijchers PJ, van de Werken H, de Wit E, Oude Vrielink JA, Elkon R, Melo SA, Léveillé N, Kalluri R, et al.. eRNAs are required for p53-dependent enhancer activity and gene transcription. Mol Cell 2013; 49:524-35; PMID:23273978; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Mousavi K, Zare H, Dell'orso S, Grontved L, Gutierrez-Cruz G, Derfoul A, Hager GL, Sartorelli V. eRNAs promote transcription by establishing chromatin accessibility at defined genomic loci. Mol Cell 2013; 51:606-17; PMID:23993744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Lam MT, Cho H, Lesch HP, Gosselin D, Heinz S, Tanaka-Oishi Y, Benner C, Kaikkonen MU, Kim AS, Kosaka M, et al.. Rev- Erbs repress macrophage gene expression by inhibiting enhancer-directed transcription. Nature 2013; 498:511-5; PMID:23728303; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature12209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Lai F, Shiekhattar R. Enhancer RNAs: the new molecules of transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2014; 25:38-42; PMID:24480293; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gde.2013.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Schueler MG, Higgins AW, Rudd MK, Gustashaw K, Willard HF. Genomic and genetic definition of a functional human centromere. Science 2001; 294(5540):109-15; PMID:11588252; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1065042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Jiang J, Birchler JA, Parrott WA, Dawe RK. A molecular view of plant centromeres. Trends Plant Sci 2003; 8(12):570-5; PMID:14659705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Dawe RK, Henikoff S. Centromeres put epigenetics in the driver's seat. Trends Biochem Sci 2006; 31(12):662-9; PMID:17074489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Birchler JA, Gao Z, Sharma A, Presting GG, Han F. Epigenetic aspects of centromere function in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2011; 14:217-22; PMID:21411364; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Topp CN, Zhong CX, Dawe RK. Centromere-encoded RNAs are integral components of the maize kinetochore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101(45):15986-91; PMID:15514020; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0407154101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Lee HR, Neumann P, Macas J, Jiang J. Transcription and evolutionary dynamics of the centromeric satellite repeat CentO in rice. Mol Biol Evol 2006; 23(12):2505-20; PMID:16987952; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/molbev/msl127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Carone DM, Longo MS, Ferreri GC, Hall L, Harris M, Shook N, Bulazel KV, Carone BR, Obergfell C, O'Neill MJ, et al.. A new class of retroviral and satellite encoded small RNAs emanates from mammalian centromeres. Chromosoma 2009; 118(1):113-25; PMID:18839199; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00412-008-0181-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Hall LE, Mitchell SE, O'Neill RJ. Pericentric and centromeric transcription: a perfect balance required. Chromosome Res 2012; 20(5):535-46; PMID:22760449; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10577-012-9297-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Ohkuni K, Kitagawa K. Endogenous transcription at the centromere facilitates centromere activity in budding yeast. Curr Biol 2011; 21:1695-703; PMID:22000103; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Chan FL, Marshall OJ, Saffery R, Kim BW, Earle E, Choo KH, Wong LH. Active transcription and essential role of RNA polymerase II at the centromere during mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109(6):1979-84; PMID:22308327; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1108705109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Huang C, Wang X, Liu X, Cao S, Shan G. RNAi pathway participates into chromosome segregation in mammalian cells. Cell Discov 2015; 1:15029; PMID:27066265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Mallm JP, Rippe K. Aurora Kinase B Regulates Telomerase Activity via a Centromeric RNA in Stem Cells. Cell Rep 2015; 11(10):1667-78; PMID:26051938; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Azzalin CM, Reichenbach P, Khoriauli L, Giulotto E, Lingner J. Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science 2007; 318:798-801; PMID:17916692; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1147182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Doksani Y, de Lange T. The role of double-strand break repair pathways at functional and dysfunctional telomeres. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014; 6:345-56; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a016576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Luke B, Lingner J. TERRA: telomeric repeat-containing RNA. EMBO J 2009; 28(17):2503-10; PMID:19629047; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Theimer CA, Feigon J. Structure and function of telomerase RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2006; 16 (3):307-18; PMID:16713250; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Theimer CA, Blois CA, Feigon J. Structure of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot reveals conserved tertiary interactions essential for function. Mol Cell 2005; 17(5):671-82; PMID:15749017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013; 495:384-8; PMID:23446346; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Memczak S1, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, et al.. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013; 495(7441):333-8; PMID:23446348; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N, Brown PO. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS One 2012; 7(2):e30733; PMID:22319583; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0030733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Chen L, Huang C, Wang X, Shan G. Circular RNAs in Eukaryotic Cells. Curr Genomics 2015; 16(5):312-8; PMID:27047251; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1389202916666150707161554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Huang C, Shan G. What happens at or after transcription:Insights into circRNA biogenesis and function. Transcription 2015; 6(4):61-4; PMID:26177684; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/21541264.2015.1071301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Capel B, Swain A, Nicolis S, Hacker A, Walter M, Koopman P, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Circular transcripts of the testis:determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell 1993; 73:1019-30; PMID:7684656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90279-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Guo JU, Agarwal V, Guo H, Bartel DP. Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome Biol 2014; 15:409; PMID:25070500; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s13059-014-0409-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]