Abstract

Background

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Existing data on cardiac structure and function in HFpEF suggests significant heterogeneity in this population.

Methods and Results

Echocardiograms were obtained from 935 patients with HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥45%) enrolled in the Treatment Of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial prior to initiation of randomized therapy. Average age was 70±10 years, 49% were female, 14% were of African descent, and co-morbidities were highly prevalent. Centralized quantitative analysis in a blinded core laboratory demonstrated a mean LVEF of 59.3±7.9%, with prevalent concentric LV remodeling (34%) and hypertrophy (43%), and left atrial (LA) enlargement (53%). Diastolic dysfunction was present in 66% of gradable participants, and was significantly associated with greater LV hypertrophy and a higher prevalence of LA enlargement. Doppler evidence of pulmonary hypertension was present in 36%. At least 1 measure of structural heart disease was present in 93% of patients.

Conclusions

Participants enrolled in TOPCAT demonstrated heterogeneous patterns of ventricular remodeling, with high prevalence of structural heart disease, including LV hypertrophy and LA enlargement, in addition to pulmonary hypertension, each of which has been associated with adverse outcomes in HFpEF. Diastolic function was normal in approximately one-third of gradable participants, highlighting the heterogeneity of the cardiac phenotype in this syndrome. These findings deepen our understanding of the TOPCAT trial population and expand our knowledge of the diversity of the cardiac phenotype in HFpEF.

Clinical Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT00094302

Keywords: Heart Failure, preserved left ventricular function, diastolic function, echocardiography

Introduction

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is common among the elderly, increasing in prevalence, and causes substantial morbidity, mortality, and resource utilization. 1,2 The three large randomized controlled trials to date have failed to identify specific therapy to improve prognosis.3,4,5 Although left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction with associated concentric remodeling is thought to be the primary cardiac perturbation underlying this heterogeneous syndrome, findings from prior HFpEF clinical trials and epidemiologic studies suggest a more diverse cardiac phenotype.6 In particular, previous epidemiologic and clinical trial imaging studies have demonstrated normal LV geometry in 30 – 45% of patients.7,8 Traditional noninvasive measures of diastolic function are normal in approximately one-third of HFpEF patients enrolled in clinical trials,7,9 while diastolic dysfunction is frequently detected in older persons without heart failure.10

The Treatment Of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) Trial was designed to determine whether treatment with spironolactone would reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HFpEF.11 Assessment of cardiac structure and function by echocardiography at baseline was prespecified in a subset of participants, with a smaller portion undergoing additional assessment at 12–18 months following randomization to either spironolactone or placebo. In this analysis, we aimed to characterize the cardiac phenotype in HFpEF patients in the TOPCAT trial, and thereby deepen our understanding of the trial population. We describe baseline cardiac structure and function in this HFpEF population and compare it with other HFpEF clinical trials and epidemiologic studies. These findings deepen our understanding of the TOPCAT trial population and expand our knowledge of the diversity of the cardiac phenotype in HFpEF.

Methods

Patient population

TOPCAT is a multicenter, international, randomized, double blind placebo-controlled trial testing the efficacy and safety of the aldosterone antagonist, spironolactone, to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in adults with signs and symptoms of HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥45% as previously described in detail.11 Briefly, TOPCAT enrolled 3,445 patients at 270 sites in 6 countries, who met the following key inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥50 years old, (2) HF defined by the presence of at least one symptom at the time of screening and one sign in the prior 12 months; (3) LVEF≥45% per local reading and obtained within 6 months prior to randomization and at least 6 months after myocardial infarction (MI) or other event that would affect LVEF; (4) controlled systolic blood pressure (BP) defined as systolic BP<140 mmHg or 140 – 160 mmHg if on 3 or more antihypertensive medications; and (5) assignment to one of two strata within which subjects were randomized: either at least one hospitalization in the prior 12 months for which HF was a major component of the hospitalization, or B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) in the prior 60 days ≥100 pg/ml or N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) ≥360 pg/ml. This study was approved by an institutional review committee at each participating site. All patients provided written informed consent. Key exclusion criteria included chronic pulmonary disease requiring home O2 or oral steroid therapy, infiltrative or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, hemodynamically significant uncorrected obstructive or regurgitant valvular heart disease or any valvular disease expected to lead to surgery during the trial, atrial fibrillation with a resting heart rate >90 bpm, MI or coronary artery bypass surgery in past 3 months, percutaneous coronary intervention in the past 30 days, and severe renal dysfunction defined as an eGFR <30 ml/min or serum creatinine ≥2.5 mg/dl.

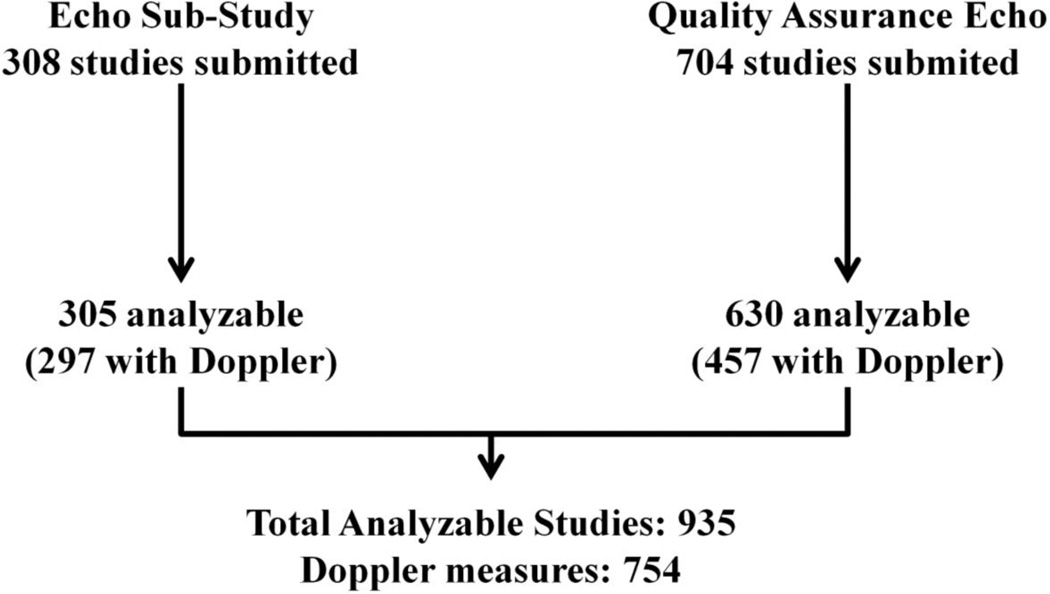

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the trial population have been previously described in detail.12 For quality control purposes, each enrolling site was required to submit echocardiographic (echo) images from at least the first 2 randomized patients for quantification of LVEF by the echo core laboratory at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Studies were performed within 6 months of randomization and were not obtained using a uniform prespecified acquisition protocol. Consent for review of these echocardiograms was obtained in the main study consent form. At 27 sites, patients consenting to participation in the overall TOPCAT trial were separately consented to participate in the echo sub-study. For participating sites, echos were performed by a study-specific protocol at baseline and 12 – 18 months following randomization. From a combined total of 1,017 baseline studies received from 204 sites, 935 studies were suitable for quantitative analysis and included in this report (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment in the TOPCAT echocardiography study.

Echocardiographic Methods

Echos were sent in digital or analog format to the echo core laboratory at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Echos from videotape were digitized and analyses were performed on an offline analysis workstation. Quantitative measures on all study echos were performed by dedicated analysts at the core laboratory, blinded to clinical information and randomized treatment assignment.

LV endocardial borders were manually traced at end-diastole and end-systole in the apical 4- and 2-chamber views and LV volumes derived according to the modified biplane Simpson’s rule. In cases where the Simpson’s method could not be used due to missing or poor quality apical views, LVEF was calculated using the Teicholz method.13 In order to minimize measurement variability and given the low prevalence of regional wall motion abnormalities, LV mass was calculated by the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) recommended formula for estimation of LV mass from LV linear dimensions and indexed to body surface area.14 LV hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as LV mass indexed to body surface area (LV mass index, LVMi) >115 g/m2 in men or >95 g/m2 in women. LV geometry was classified based on relative wall thickness (RWT), defined as (2*diastolic posterior wall thickness)/LV end-diastolic dimension, and LVMi as recommended by the ASE: normal – RWT≤0.42 and no LVH; eccentric hypertrophy – RWT≤0.42 and LVH; concentric remodeling – RWT>0.42 and no LVH; concentric hypertrophy – RWT>0.42 and LVH. Mitral regurgitation (MR) was categorized by tracing the MR jet area (obtained with color Doppler imaging) occupying the left atrium in 4- and 2-chamber views and was expressed as a proportion of left atrial (LA) area. The presence of an eccentric jet raised the grade of MR by 1 degree.15 LA volume was assessed by the biplane area-length method from apical 2- and 4-chamber views at end-systole from the frame preceding mitral valve opening, and was indexed to body surface area (LA volume index, LAVi). Left atrial enlargement was determined based on LA area, volume, and volume index based on guideline recommendations.14 Peak early diastolic tissue velocity (E’) was measured from the septal and lateral aspects of the mitral annulus. Mitral inflow velocity was assessed by pulsed wave Doppler from the apical 4-chamber view, by positioning the sample volume at the tip of the mitral leaflets. The deceleration time of the E wave was measured as the interval from the peak E wave to its extrapolation to the baseline. E/E’ ratio was calculated as E wave divided by E’. Diastolic dysfunction grade was derived from mitral inflow E/A ratio, tissue Doppler E’ and deceleration time.16 Diastolic dysfunction was graded as follows: mild – reduced E’ (septal <8 cm/sec or lateral <10 cm/sec) and E/A ratio ≤0.8; moderate – reduced E’ and E/A ratio of 0.8 to 1.5; severe – reduced E’ and E/A ratio >1.5 or E wave deceleration time <160 msec. Diastolic dysfunction was only graded among participants in sinus rhythm at the time of echo. Due to the limited feasibility of obtaining reliable pulmonary venous flow data, pulmonary venous Doppler pattern was not measured. Right ventricular (RV) function, expressed as the RV fractional area change (RVFAC), was assessed as the percent change in cavity area from end-diastole to end-systole in accordance with ASE guidelines.17 Peak tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity was measured and peak RV-to-RA systolic gradient was calculated as 4·(peak TR velocity)2. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was estimated as 0.1618 + (10.006*[peak TR velocity/RVOT VTI]).18

An experienced echocardiographer (A.M.S.) over-read all quantitative measures and qualitatively assessed each study for the presence of regional wall motion abnormalities, in addition to the presence and severity of aortic insufficiency, mitral stenosis, tricuspid regurgitation, and right ventricular enlargement. Aortic insufficiency grade was assessed primarily based on the width of the color Doppler jet at the level of the aortic valve in the parasternal long and short axis views, in addition to the percent of the LV outflow tract diameter occupied by the aortic regurgitation color Doppler signal in the parasternal long axis view.19 Mitral stenosis assessment was based on the mean antegrade transmitral gradient from continuous wave Doppler, with mild defined as a mean gradient <5 mmHg, moderate as 5–10 mmHg, and severe as >10 mmHg. Tricuspid regurgitation severity was based primarily on the size of the regurgitant color Doppler signal relative to the right atrial size. Evaluations were performed only on images with color Doppler Nyquist limit ≥50 cm/sec.

Three hundred and five of 308 (99%) sub-study echocardiograms and 630 of 704 (89%) quality assurance echocardiograms could be analyzed quantitatively (Figure 1). Of the 935 analyzable studies included in this analysis, complete 2D and Doppler data were available in 553 (59%), with all Doppler measures missing in 181 (19%), and tissue Doppler only missing in an additional 147 (16%) patients. Among the 78% of participants with Doppler measures, 76% were in sinus rhythm.

Each measure was performed by the same analyst for all study participants. Intra-observer variability in our laboratory, performed in 60 studies, are as follows: wall thickness: coefficient of variation: 12%, bias 0.02±0.1 cm; LV end-diastolic volume (EDV): coefficient of variation 12%, bias 1.6±10.5 ml; LV end-systolic volume (ESV): coefficient of variation 18%, bias 2.6±5.9 ml; LVEF: coefficient of variation 6.6%, bias 2.0±4.3%; tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) E’: coefficient of variation 7.0%, bias 0.1±0.4 cm/sec; E/E’ ratio: coefficient of variation 11%, bias 0.2±1.2.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations or median and interquartile range as specified. Comparison of baseline clinical measures between TOPCAT patients included (n=935) and not included (n=2,510) in the echo cohort, and comparison of cardiac structure and function based on TOPCAT entry criteria, were performed using a Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and a t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables as specified. Two-sided P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 and Stata version 11.

Results

The average age of the 935 TOPCAT patients in the pooled echo analysis was 70±10 years old, 49% were female, 14% were of African descent, and 11% were Hispanic. Co-morbidities included hypertension (91%), coronary artery disease (57%), atrial fibrillation (38%), diabetes (40%), and chronic kidney disease (42%). The majority of patients were receiving therapy with beta-blockers (81%), inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system (ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers; 81%), and diuretics (83%). Compared to TOPCAT patients not in the pooled echo analysis, patients participating in the echo cohort were older, more frequently of African descent, had a higher BMI, and had a higher prevalence of co-morbidities, including diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), prior coronary revascularization, atrial fibrillation, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma (Table 1). Patients in the echo cohort were also more frequently enrolled in the U.S. (52%). Compared to patients in the echo cohort without missing echo data, participants with missing data were more frequently male and white, had a lower prevalence of CKD and prior percutaneous coronary intervention, and had higher diastolic blood pressure, eGFR, and hematocrit.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of TOPCAT patients included compared to those not included in the echocardiographic sub-study.

| Characteristic | Overall (3445) |

Echo (935) |

Non- Echo(2510) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 68.6±9.6 | 69.9±9.7 | 68.1±9.5 | <0.0001 |

| Female gender, n(%) | 1775(52) | 462(49) | 1313(52) | 0.14 |

| Race/ethnicity, n(%) | ||||

| White | 3062(89) | 770(82) | 2292(91) | <0.0001 |

| Black/African American | 302(9) | 127(14) | 175(7) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 321(9) | 103(11) | 218(9) | 0.04 |

| Native American/Alaskan native | 10(<1) | 5(<1) | 5(<1) | 0.15 |

| Asian | 19(1) | 4(<1) | 15(<1) | 0.80 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1(<1) | 0(0) | 1(<1) | |

| Other | 70(2) | 31(3) | 39(2) | 0.002 |

| Country | <0.0001 | |||

| US | 1151(33) | 483(52) | 668(27) | |

| Canada | 326(9) | 101(11) | 225(9) | |

| Russia | 1066(31) | 242(26) | 824(33) | |

| Republic of Georgia | 612(18) | 39(4) | 573(23) | |

| Brazil | 167(5) | 42(5) | 125(5) | |

| Argentina | 123(4) | 28(3) | 95(4) | |

| Comorbitidies, n(%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 3147(91) | 854(91) | 2293(91) | 1.0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 893(26) | 253(27) | 640(26) | 0.36 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 500(15) | 164(18) | 336(13) | 0.003 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 443(13) | 144(15) | 299(12) | 0.007 |

| Angina pectoris | 1613(47) | 391(42) | 1222(49) | 0.0004 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2023(59) | 533(57) | 1490(59) | 0.23 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1213(35) | 359(38) | 854(34) | 0.02 |

| Pacemaker | 269(8) | 94(10) | 175(7) | 0.003 |

| Implanted cardioverter-defibrillator | 44(1) | 14(2) | 30(1) | 0.50 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1114(32) | 373(40) | 741(30) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1311(38) | 391(42) | 920(37) | 0.006 |

| Obesity | 1902(55) | 538(58) | 1364(55) | 0.11 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2073(60) | 639(68) | 1434(57) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 403(12) | 127(14) | 276(11) | 0.04 |

| Asthma | 223(6) | 74(8) | 149(6) | 0.04 |

| Stroke | 265(8) | 77(8) | 188(8) | 0.47 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 319(9) | 90(10) | 229(9) | 0.64 |

| Medications, n(%) | ||||

| Diuretic | 2785(81) | 774(83) | 2011(80) | 0.10 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 2260(66) | 566(61) | 1694(68) | 0.0001 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 672(20) | 203(22) | 469(19) | 0.053 |

| Beta-blocker | 2731(79) | 753(81) | 1978(79) | 0.30 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1285(37) | 355(38) | 930(37) | 0.66 |

| Hypoglycemic agent | 959(28) | 331(35) | 628(25) | <0.0001 |

| Other cardiovascular medication | 3115(91) | 853(91) | 2262(90) | 0.40 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Smoking, n(%) | 0.35 | |||

| Current | 360(10) | 81(9) | 279(11) | |

| Past | 1268(37) | 394(42) | 874(35) | |

| Never | 1813(53) | 459(49) | 1354(54) | |

| Activity level (metabolic equivalents/week) * | 9.3(1.5,28.0) | 5.8(1.0,17.5) | 11.3(2.0,28.0) | <0.0001 |

| Physical characteristics | ||||

| Weight, kg | 89.7±22.1 | 91.4±23.6 | 89.1±21.5 | 0.01 |

| Height, cm | 167.0±10.2 | 167.1±10.9 | 167.0±10.0 | 0.82 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 105.0±16.8 | 105.7±16.6 | 104.7±16.9 | 0.13 |

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 32.1±7.3 | 32.6±7.5 | 31.9±7.2 | 0.01 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 69.1±10.4 | 69.1±11.1 | 69.1±10.1 | 0.89 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 129.2±14.0 | 128.1±14.8 | 129.6±13.6 | 0.005 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75.8±10.6 | 73.6±10.7 | 76.6±10.5 | <0.0001 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 53.4±12.3 | 54.6±13.0 | 53.0±12.0 | 0.001 |

| Electrolytes, renal function, and glucose | ||||

| Sodium, mEq/L | 141.2±4.2 | 140.6±4.1 | 141.4±4.2 | <0.0001 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.3±0.4 | 4.2±0.4 | 4.3±0.5 | 0.06 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.09±0.30 | 1.13±0.32 | 1.06±0.29 | <0.0001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtrate rate, ml/min/1.73m2 | 68.6±21.4 | 66.8±22.0 | 69.2±21.2 | 0.004 |

| Complete blood count | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.3±1.7 | 13.1±1.7 | 13.4±1.7 | <0.0001 |

| Hematocrit, % | 40.1±5.1 | 39.3±5.0 | 40.4±5.0 | <0.0001 |

Numbers represent mean ± S.D. for continuous variables and N (%) for categorical variables. Between group comparisons for continuous variables was performed using t-test.

Median and interquartile range, rank sum test.

Left Ventricular Structure and Systolic Function

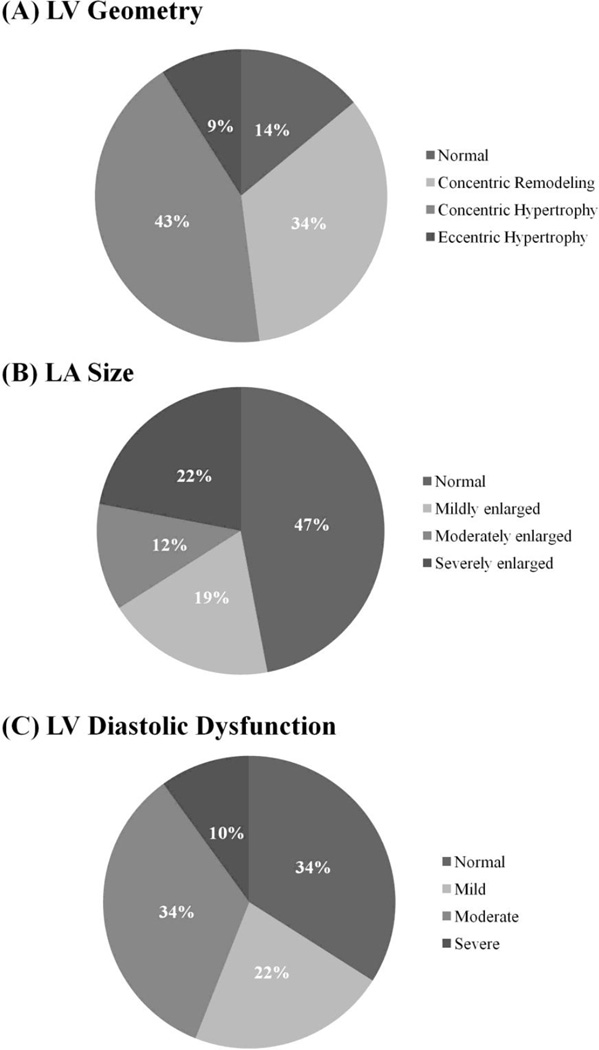

Consistent with trial inclusion criteria, the mean LVEF was 59.3±7.9%, with core laboratory LVEF <50% in only 13% and an LVEF <45% in 5% (Table 2). Despite preserved ejection fraction, LV longitudinal shortening reflected in TDI S’ was significantly reduced. The majority of patients demonstrated normal LV size but increased wall thickness. Elevated LV RWT was present in 78%, and concentric LV hypertrophy was present in 44% of participants (Figure 2A). Eccentric hypertrophy was also found in 9% of participants, and was associated with lower LVEF. Focal regional wall motion abnormalities, suggestive of prior myocardial infarction, were noted in 7% of participants (n=70).

Table 2.

Cardiac structure and function in the TOPCAT echocardiography study.

| N | Median (Q1-Q3) | N (%) Abnormal |

Abnormal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV structure | ||||

| LVEDVi (ml/m2) | 862 | 47.2 (38.9 – 58.2) | 50 (6%) | >75 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) | 862 | 18.6 (14.1 – 24.0) | 114 (13%) | >30 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 878 | 4.80 (4.41 – 5.17) | 71 (8%) | >5.3 (F), 5.9 (M) |

| LVESD (cm) | 878 | 3.35 (3.00 – 3.65) | - | - |

| Septal wall thickness (cm) | 878 | 1.18 (1.05 – 1.32) | 813 (93%) | >0.9(F), 1.0(M) |

| Posterior wall thickness (cm) | 877 | 1.13 (1.02 – 1.27) | 783 (89%) | >0.9(F), 1.0(M) |

| LV mass index (mg/m2) | 875 | 108 (90 – 128) | 456 (52%) | >95(F), >115(M) |

| Relative wall thickness | 877 | 0.47 (0.42 – 0.53) | 675 (77%) | >0.42 |

| LV geometry | 875 | |||

| Normal | 119 (14%) | |||

| Concentric remodeling | 300 (34%) | |||

| Concentric hypertrophy | 373 (43%) | |||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 83 (9%) | |||

| LV systolic function | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 935 | 60.1 (55.6 – 64.3) | 117 (13%) | <50% |

| TDI S’ (lateral) (cm/sec) | 499 | 6.5 (5.4 – 7. 7) | ||

| TDI S’ (septal) (cm/sec) | 508 | 5.6 (4.7 – 6.6) | ||

| LV diastolic function | ||||

| E/A ratio | 553 | 1.03 (0.77 – 1.49) | <0.8: 153 (28%) >1.5: 138 (25%) |

|

| TDI E’ (lateral) (cm/sec) | 503 | 7.6 (5.9 – 9.8) | 386 (77%) | <10 |

| TDI E’ (septal) (cm/sec) | 511 | 5.6 (4.6 – 7.3) | 429 (83%) | <8 |

| E/E’ (lateral) | 493 | 10.5 (7.9 – 14.3) | 191 (39%) | ≥12 |

| E/E’ (septal) | 499 | 14.7 (10.5 – 18.7) | 9–15: 192 (38%) ≥15: 236 (47%) |

|

| LAVi (ml/m2) | 834 | 27.9 (21.2 – 35.1) | 381 (46%) | ≥29 |

| LA diameter (cm) | 878 | 4.19 (3.84–4.66) | 564 (64%) | >4.0 |

| Diastolic Dysfunction Grade | 490 | |||

| Normal | 166 (34%) | |||

| Mild | 108 (22%) | |||

| Moderate | 169 (34%) | |||

| Severe | 47 (10%) | |||

| Pulmonary Vascular and RV | ||||

| TR jet velocity (m/sec) | 450 | 2.70 (2.44 – 3.04) | 162 (36%) | >2.9 |

| RV-RA gradient (mmHg) | 450 | 29 (24 – 37) | ||

| PVR (Woods units) | 324 | 1.76 (1.48 – 2.13) | 35 (11%) | >2.5 |

| RVFAC (%) | 673 | 48.8 (43.7 – 53.8) | 29 (4%) | <35% |

EDD – LV end-diastolic dimension; ESD – LV end-systolic dimension; EDVi – LV end-diastolic volume indexed to BSA; EDVi – LV end-systolic volume indexed to BSA; LVEF - LV ejection fraction; LAVi – left atrial volume indexed to BSA; E wave – peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity; A wave – peak late diastolic transmitral flow velocity; E’ lateral – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at lateral mitral annulus; E’ septal – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at septal mitral annulus; TR – tricuspid regurgitation; PVR – pulmonary vascular resistance; FAC – fractional area change.

Figure 2.

Pie charts demonstrating the prevalence of (A) LV geometry (n=875), (B) left atrial enlargement (n=836), and (C) LV diastolic dysfunction grade in the TOPCAT echocardiography study (n=490).

Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

LA size was enlarged in 53% of patients (Figure 2B), with moderate or severe left atrial enlargement noted in 34% of participants. Including LA anterior-posterior dimension >4.0 cm as an additional criteria, the prevalence of LA enlargement increased to 80%. Only 7% of patients demonstrated normal LV and LA structure. Both lateral and septal TDI E’ were impaired in the majority of patients. Elevated LV filling pressure, defined by a septal E/E’ ≥15 or lateral E/E’ ≥12, was present in 51%, and was associated with a higher prevalence of left atrial enlargement (62% with elevated E/E’ ratio versus 52% without, p=0.03). Diastolic grade could not be determined in 445 participants, due to atrial fibrillation in 25%, no tissue Doppler measures in 72%, and additionally no mitral inflow Doppler E wave in 3%. Among the 52% of patients in whom diastolic dysfunction grade could be determined, diastolic dysfunction was present in 66%, with moderate or severe dysfunction in 44% (Figure 2C). Worse diastolic dysfunction grade was significantly associated with higher prevalence of LV hypertrophy (p = 0.02), both concentric and eccentric.

Pulmonary Vasculature and the Right Ventricle

Among patients with measurable TR jet (n=450), the peak velocity was elevated to >2.9 m/sec in 36%. Among the 162 of these participants with a jet velocity >2.9 m/sec, the mean TR velocity was 3.28±0.33 m/sec. TR jet was ≥3.5 m/sec in 37 (8%) and was ≥4.0 m/sec in 8 (2%). TR jet velocity was significantly related to the E/E’ ratio (septal: r=0.29, p<0.0001; lateral: r=0.23, p<0.0001). In the subset of 324 patients in whom PVR could be estimated echocardiographically, PVR exceeded 2.5 Woods units in 11%. RV FAC was within reference limits in the majority of participants (median 0.49, Q1–Q3 0.44 – 0.54). RV FAC was <0.45 in 31% of patients, <0.40 in 11%, and <0.35 (the abnormal cut-off per ASE guidelines) in 4%. Some degree of RV enlargement was noted in 11% of patients, and was moderate or severe in 5%.

Mitral and Aortic Valve Disease

Mitral regurgitation was detected in 61% of patients, with moderate or greater regurgitation present in 12% of patients overall. Mitral stenosis was rare, noted in 1.2% and was mild in the large majority. Peak antegrade transaortic velocity was obtained in 623 patients, among whom mild aortic stenosis (peak velocity of 2.0 – 3.0 m/sec) was present in 10%, and moderate stenosis (peak velocity 3.0 – 4.0 m/sec) was present in 1.1%. Mild aortic regurgitation was noted in 9%, and moderate regurgitation was noted in 1.3%. Prior replacement of the mitral and/or aortic valve was noted in 28 patients (3%; 6 mitral only, 19 aortic only, 3 both). Finally, at least moderate tricuspid regurgitation was noted in 55 patients (6%).

Impact of Trial Entry Criteria on Cardiac Structure and Function

Entry into TOPCAT required either hospitalization within the prior 12 months for which HF was a major component or BNP ≥100 pg/ml or NT-proBNP ≥360 pg/ml within the prior 60 days. Patients qualifying only by biomarker criteria (33%) tended to be older, had a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and prior coronary revascularization, and were more likely to be enrolled in the U.S. or Canada. Despite these differences, LV structure differed modestly between groups. Participants with a HF hospitalization within the prior 12 months demonstrated slightly higher wall thickness (Table 3). Echocardiographic markers of elevated LV filling pressure – namely LAVi and E/A ratio – were higher among participants enrolled solely based on biomarker criteria. These differences in LAVi and E/A ratio remained significant after adjusting for age and history of atrial fibrillation. Participants enrolled based on biomarker criteria also demonstrated lower systolic longitudinal velocity despite similar LVEF.

Table 3.

Cardiac structure and function based on TOPCAT entry criteria.

| HF hospitalization in prior 12 months (n=622) |

NT-proBNP or BNP criteria only (n=313) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (Q1-Q3) | N | Median (Q1-Q3) | ||

| LV structure | |||||

| LVEDD (cm) | 574 | 4.82 (4.45–5.17) | 304 | 4.77 (4.33–5.16) | 0.13 |

| LVESD (cm) | 574 | 3.38 (3.01–3.65) | 304 | 3.33 (2.95–3.64) | 0.16 |

| LVEDVi (ml/m2) | 566 | 48.0 (39.6–58.2) | 296 | 45.8 (38.6–57.4) | 0.08 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) | 566 | 18.8 (14.4–24.5) | 296 | 18.1 (13.7–23.2) | 0.06 |

| Septal wall thickness (cm) | 574 | 1.19 (1.07–1.32) | 304 | 1.16 (1.02–1.32) | 0.03 |

| Posterior wall thickness (cm) | 573 | 1.15 (1.04–1.28) | 304 | 1.11 (1.00–1.26) | 0.02 |

| LV mass index (mg/m2) | 572 | 110 (91–128) | 303 | 107 (87–128) | 0.13 |

| LV hypertrophy (%) | 54% | 49% | 0.07 | ||

| Relative wall thickness | 573 | 0.48 (0.43–0.53) | 304 | 0.47 (0.42–0.53) | 0.23 |

| LV geometry | 0.10 | ||||

| Normal | 13% | 16% | |||

| Concentric remodeling | 33% | 36% | |||

| Concentric hypertrophy | 45% | 37% | |||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 9% | 11% | |||

| LV systolic function | |||||

| LVEF (%) | 622 | 59.9 (55.4–64.0) | 313 | 60.8 (56.0–65.2) | 0.12 |

| TDI S’ (lateral) (cm/sec) | 315 | 6.6 (5.6–7.7) | 184 | 6.3 (5.3–7.5) | 0.06 |

| TDI S’ (septal) (cm/sec) | 329 | 5.7 (4.9–6.8) | 179 | 5.4 (4.5–6.4) | 0.004 |

| LV diastolic function | |||||

| E/A ratio | 361 | 1.00 (0.74–1.44) | 192 | 1.14 (0.85–1.67) | 0.01 |

| TDI E’ (lateral) (cm/sec) | 317 | 7.5 (5.7–9.6) | 186 | 7.8 (6.1–9.9) | 0.57 |

| TDI E’ (septal) (cm/sec) | 330 | 5.7 (4.6–7.2) | 181 | 5.5 (4.6–7.4) | 0.92 |

| E/E’ (lateral) | 310 | 10.5 (7.8–14.2) | 183 | 10.6 (8.0–15.1) | 0.25 |

| E/E’ (septal) | 322 | 14.4 (10.2–18.7) | 177 | 15.0 (11.4–19.1) | 0.26 |

| LAVi (ml/m2) | 543 | 26.6 (20.5–33.8) | 291 | 30.3 (23.0–38.9) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic Dysfunction Grade | 317 | 173 | 0.06 | ||

| Normal | 33% | 36% | |||

| Mild | 25% | 16% | |||

| Moderate | 34% | 35% | |||

| Severe | 8% | 13% | |||

| Pulmonary Vascular & RV | |||||

| TR jet velocity (m/sec) | 267 | 2.68 (2.43–3.03) | 183 | 2.74 (2.48–3.04) | 0.42 |

| RVFAC (%) | 429 | 48.8 (44.1–53.8) | 244 | 48.7 (43.1–53.8) | 0.87 |

Between group comparisons are performed using a rank sum test.

EDD – LV end-diastolic dimension; ESD – LV end-systolic dimension; EDVi – LV end-diastolic volume indexed to BSA; EDVi – LV end-systolic volume indexed to BSA; LVEF - LV ejection fraction; LAVi – left atrial volume indexed to BSA; E wave – peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity; A wave – peak late diastolic transmitral flow velocity; E’ lateral – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at lateral mitral annulus; E’ septal – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at septal mitral annulus; TR – tricuspid regurgitation; FAC – fractional area change.

Discussion

Among 935 patients enrolled in TOPCAT, we found a high prevalence of structural heart disease, including concentric LV remodeling, concentric hypertrophy, and LA enlargement. Indeed, only 7% of participants demonstrated normal LV geometry and normal LA size. Over one third of patients with measurable TR jet velocity demonstrated evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Each of these echocardiographic characteristics has been associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes in HFpEF, and together suggest that the TOPCAT cohort represents a particularly high risk group of patients with the HFpEF syndrome.7,20 Doppler-based diastolic function grade, which has only inconsistently been associated with outcomes in HFpEF,7,9 was normal in one-third of evaluable participants. These findings enhance our understanding of the HFpEF population tested in TOPCAT, and suggest that they may represent a particularly high risk group within the HFpEF syndrome.

We noted a higher prevalence of LVH, increased LV wall thickness, and higher mass index in TOPCAT compared to epidemiologic cohorts (Table 4).8,21–27 A notable exception is African Americans with HFpEF from the Jackson, MS site of the NHLBI ARIC study, who demonstrated an even higher prevalence of LV hypertrophy than seen in this cohort.24 In general, the pattern of ventricular remodeling noted in TOPCAT more closely approximated that from a large HFpEF registry.ww

Table 4.

Cardiac structure and function in TOPCAT compared to HFpEF patients in select epidemiology and registry studies.

| TOPCAT | Olmsted County8 |

CHS21 | Strong Heart Study22 |

He et al.23 | ARIC/ Jackson24 |

NY HF Registry25 |

French Registry26 |

Northwestern Registry27 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 935 | 244 | 167 | 50 | 128 | 85 | 619 | 368 | 402 |

| LVEF cut-off | ≥45% | ≥50% | ≥55%* | >54% | >55% | ≥50% | ≥50% | ≥50% | >50% |

| Age (years) | 69.9±9.7 | 76 (22–99) | 76±7 | 64±8 | 72±10 | 61 (57–67) | 71.7±14.1 | 76±10 | 65±13 |

| Female | 49% | 55% | 57% | 84% | 45% | 85% | 73% | 53% | 62% |

| LV Structure | |||||||||

| EDD (cm) | 4.80±0.58 | NA | 5.1±0.8 | 5.04±0.65 | 4.7±0.6 | 4.4 (4.1–4.7) | 4.70±0.76 | 5.0±0.8 | 4.63±0.63 |

| ESD (cm) | 3.37±0.51 | NA | 3.0±0.7 | NA | 3.1±0.5 | 2.6 (2.4–3.0) | 3.21±0.73 | 3.3±0.7 | 2.94±0.65 |

| EDVi (ml/m2) | 49.9±15.5 | 56.4±14.4 | 69±22 | NA | 53±16 | NA | NA | NA | 40.6±11.0 |

| ESVi (ml/m2) | 20.7±9.8 | NA | 20±10 | NA | 20±8 | NA | NA | NA | 16.2±6.3 |

| Septal WT (cm) | 1.20±0.21 | NA | NA | 0.99±0.14 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | NA | NA | 1.21±0.29 |

| Posterior WT (cm) | 1.16±0.20 | NA | 0.9±0.2 | 0.92±0.11 | 1.1±0.2 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 1.16±0.26 | ||

| LV Mass (g) | 223±71 | 200.4±67.1 | 176±64 | 178±51 | 215±69 | 239 (202–285) | NA | NA | 210±79 |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 111±31 | 102.1±29.0 | 98±34 | 96±24 | 118±36 | NA | 66 (53–85) | NA | 103±38 |

| Hypertrophy | 52% | 42% | NA | NA | NA | 75% | NA | NA | 60% |

| RWT | 0.49±0.10 | 0.45±1.0 | 0.36±0.11 | 0.37±0.06 | NA | 0.57 (0.51–0.62) | NA | NA | 0.51±15 |

| LV geometry | |||||||||

| Normal | 14% | 31% | NA | NA | NA | 5% | NA | NA | 12% |

| Concentric remodeling | 34% | 27% | NA | NA | NA | 20% | NA | NA | 28% |

| Concentric hypertrophy | 43% | 26% | NA | NA | NA | 73% | NA | NA | 48% |

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 9% | 16% | NA | NA | NA | 2% | NA | NA | 12% |

| LV Systolic Function | |||||||||

| EF (%) | 59.6±8.0 | 62±6 | 72±7 | 64±9 | 64±5 | 67 (59–75) | 59.8±7.3 | 63±8 | 61±6 |

| LV Diastolic Function | |||||||||

| LAVi (ml/m2) | 29.8±12.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 34±14 |

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.3±0.6 | NA | NA | NA | 3.9±0.5 | 3.4 (3.1–3.8) | 4.1±0.7 | NA | |

| E/A ratio | 1.2±0.7 | 1.21±0.69 | 1.3±1.2 | 0.75±0.28 | 1.1±0.8 | 0.94 (0.79–1.12) | NA | NA | 1.4±0.7 |

| TDI E’ septal (cm/s) | 6.1±2.2 | 6.0±2.1 | NA | NA | 8±2 | NA | NA | NA | 7.0±2.7 |

| TDI E’ lateral (cm/s) | 8.2±3.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.3±3.9 |

| E/E’ ratio (septal) | 15.6±6.8 | 18.4±9.7 | NA | NA | 10 | NA | NA | NA | 17±9 |

| Diastolic Dfxn (y/n) | 66% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 27% | NA | NA | 91% |

| Pulmonary Pressure | |||||||||

| TR velocity (m/sec) | 2.8±0.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | PASP: 47±17 | NA | 3.0±0.6 |

Values in italics were estimated by the author from primary data provided in the referenced manuscripts.

EDD – LV end-diastolic dimension; ESD – LV end-systolic dimension; EDVi – LV end-diastolic volume indexed to BSA; EDVi – LV end-systolic volume indexed to BSA; LVEF - LV ejection fraction; WT – wall thickness; LVMI – LV mass index; RWT – relative wall thickness; LAVi – left atrial volume indexed to BSA; E wave – peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity; A wave – peak late diastolic transmitral flow velocity; E’ lateral – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at lateral mitral annulus; E’ septal – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at septal mitral annulus; TR – tricuspid regurgitation

Compared to data from the echo sub-study of the I-PRESERVE trial, which is the most comparable in size and comprehensiveness, LV size was similar although wall thickness tended to be greater in TOPCAT,7 resulting in a higher prevalence of concentric remodeling and concentric hypertrophy . The reason for this difference is unclear, as the prevalence of major co-morbidities – including hypertension, diabetes, and coronary disease – was similar between studies. The average eGFR was modestly lower in TOPCAT. In addition, African Americans appear to develop greater degrees of concentric LV remodeling28 and LV hypertrophy29 for a set degree of hypertension and demonstrate greater hypertrophy in HFpEF.24 One potential contributor to the higher LV mass index and concentricity noted in TOPCAT might be the greater representation of blacks (14%) compared to I-PRESERVE (2%). Greater variability in ventricular structure exists when looking more broadly at HFpEF clinical trials (Table 5),4,7,9,30–32 with appreciably larger LV size observed in the CHARMES and PARAMOUNT trials. 9,30 Interestingly, we noted an eccentric pattern of hypertrophy in 9% of participants, consistent with findings from the PARAMOUNT trial (eccentric hypertrophy in 7%) and the Olmsted County epidemiologic cohort (eccentric hypertrophy in 16%).8 While increased wall thickness-to-cavity ratio with diminished cavity size is the commonly expected pattern of remodeling in HFpEF, these findings suggest heterogeneity of the cardiac phenotype in the HFpEF syndrome.

Table 5.

Cardiac structure and function in TOPCAT compared to select HFpEF clinical trials enrolling at least 100 patients.

| TOPCAT | PARAMOUNT30 | Aldo-DHF31 | RELAX32 | I-PRESERVE7 | CHARMES9 | PEP-CHF4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 935 | 292 | 422 | 216 | 745 | 312 | 850 |

| Key Inclusion Criteria |

LVEF≥45% HF hospitalization or BNP≥100 or NT-proBNP ≥360 pg/ml |

LVEF≥45% NT-pBNP>400 |

LVEF≥50% Echo DD or AF pV02≤25 |

LVEF≥50% NT-pBNP>400 pV02<60% pred |

LVEF≥45% NSR at echo |

LVEF>40% | LVEF>40% DHF by clin, echo criteria |

| Age (years) | 69.9±9.7 | 70.6±9.1 | 67 ± 8 | 69,62–77 | 72±7 | 66±11 | 75, 72–79 |

| Female | 49% | 56% | 52% | 48% | 62% | 34% | 56% |

| LV Structure | |||||||

| EDD (cm) | 4.80±0.58 | 4.64±0.48 | 4.65±0.62 | 4.6, 4.3–5.1 | 4.8±0.6 | 5.4±0.7 | 4.6, 4.2–5.1 |

| ESD (cm) | 3.37±0.51 | 2.99±0.70 | 2.55±0.64 | NA | 3.2±0.7 | 3.6±0.7 | NA |

| EDVi (ml/m2) | 49.9±15.5 | 61.4±15.4 | NA | NA | 49±14 | NA | NA |

| ESVi (ml/m2) | 20.7±9.8 | 26.5±10.4 | NA | NA | 18±9 | NA | NA |

| MWT (cm) | 1.18±0.20 | 0.91±0.16 | NA | NA | 0.93±0.15 | NA | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) |

| LV Mass (g) | 223±71 | 148±43 | NA | NA | 164±48 | 237±91 | NA |

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | 111±31 | 79.1±22.2 | 109±28 | 78, 62–94 | NA | 117±42 | NA |

| Hypertrophy | 52% | 14% | NA | 48% | 29% | NA | NA |

| RWT | 0.49±0.10 | 0.38±0.08 | NA | NA | 0.40±0.08 | NA | NA |

| Concentric form of remodeling | 77% | 21% | NA | 46% | 54% | NA | NA |

| LV geometry | |||||||

| Normal | 14% | 72% | NA | NA | 46% | NA | NA |

| Concentric remodeling | 34% | 14% | NA | NA | 25% | NA | NA |

| Concentric hypertrophy | 43% | 7% | NA | NA | 29% | NA | NA |

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 9% | 7% | NA | NA | 0% | NA | NA |

| LV Systolic Function | |||||||

| EF (%) | 59.6±8.0 | 57.7±7.9 | 67 ± 8 | 60, 56–65 | 64±9 | 50, 18–65 | 65 (56–66) |

| LV Diastolic Function | |||||||

| LAVi (ml/m2) | 29.8±12.5 | 35.9±13.5 | 28.0±8.4 | 44, 36–59 | - | 41.3±14.7 | NA |

| LA Area (cm2) | 19.6±5.2 | 21±5 | - | - | 23±6 | NA | NA |

| LA Diameter (cm) | 4.3±0.6 | 3.7±0.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.5 (4.1–4.8) |

| E/A ratio | 1.2±0.7 | 1.1±0.62 | 0.91±0.33 | 1.5, 1.0–2.1 | 1.05±0.74 | 1.1±0.7 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| TDI E’ septal (cm/s) | 6.1±2.2 | 5.8±2.0 | 5.9±1.3 | 6, 5–8 | 7.2±2.9 | NA | NA |

| TDI E’ lateral (cm/s) | 8.2±3.2 | 7.5±2.8 | - | - | 9.1±3.4 | NA | NA |

| E/E’ ratio (septal) | 15.6±6.8 | 15.9±7.3 | 12.8±4.0 | 16,11–24 | - | NA | NA |

| E/E’ ratio (lateral) | 11.8±5.9 | 12.7±7.4 | - | - | 10.0±4.5 | NA | NA |

| Diastolic Dysfxn (y) | 66% | 92% | 100% | NA | 69% | 67% | NA |

| None | 34% | 8% | 0% | NA | 31% | 33% | NA |

| Grade 1 | 22% | 31% | 77% | NA | 29% | 22% | NA |

| Grade 2 | 34% | 43% | 21% | NA | 36% | 37% | NA |

| Grade 3 | 10% | 18% | 2% | NA | 4% | 7% | NA |

| Pulmonary Pressure | |||||||

| TR velocity (m/sec) | 2.8±0.5 | 2.5±0.4 | NA | 41, 33–53 (RVSP) | 37±13 (RVSP) | NA | NA |

Values in italics were estimated by the author from primary data provided in the referenced manuscripts.

EDD – LV end-diastolic dimension; ESD – LV end-systolic dimension; EDVi – LV end-diastolic volume indexed to BSA; EDVi – LV end-systolic volume indexed to BSA; LVEF - LV ejection fraction; WT – wall thickness; LVMI – LV mass index; RWT – relative wall thickness; LAVi – left atrial volume indexed to BSA; E wave – peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity; A wave – peak late diastolic transmitral flow velocity; E’ lateral – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at lateral mitral annulus; E’ septal – peak early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity at septal mitral annulus; TR – tricuspid regurgitation

Doppler-based measures of diastolic function were normal in approximately one-third of our patients in sinus rhythm. Previous, relatively small, invasive hemodynamic studies in select highly phenotyped HFpEF patients demonstrated a high prevalence of diastolic dysfunction, characterized by both prolongation of early diastolic active relaxation and increase in left ventricular passive stiffness.33,34 However, clinical trials likely include a broader and more diverse HFpEF population and the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in TOPCAT is nearly identical to findings from both the I-PRESERVE echo sub-study and CHARMES.7,9 Importantly, limited normative data for diastolic measures exist in the elderly represented in TOPCAT and limit our confidence in defining ‘abnormal’ in this cohort. In particular, for tissue Doppler relaxation velocities central to current grading schemes, even the largest studies to provide normal ranges for healthy community dwelling individuals without prevalent CV risk factors included only ~100 subjects older than 70 years.35,36 Left atrial enlargement, considered an integrator of LV diastolic function and dependent on left atrial filling pressure, was present in the majority of TOPCAT participants.

The characteristics of patients with HFpEF have varied depending on the cohort studied, due both to the inherent heterogeneity of the syndrome and the cohort specific inclusion criteria. Within TOPCAT, we also observed echo differences based on study inclusion criteria, with more prominent markers of elevated filling pressure, including larger LAVi and higher E/A ratio, among participants enrolled on the basis of elevated BNP or NT-proBNP levels, as opposed to recent hospitalization with HF. These findings could help account for the greater degree of left atrial enlargement noted in clinical trials with a uniform entry requirement for an elevated NT-proBNP, such as PARAMOUNT and RELAX.30,32 The previously noted distinctions between clinical trials and observational epidemiologic studies also may reflect trial-specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, and inclusion of a broader range of patients – possibly with more comorbidities – in the observational studies.

Concomitant pulmonary hypertension is a risk factor for adverse outcomes in HFpEF.20 We found Doppler evidence of pulmonary hypertension in 36% of patients, likely consistent with findings from other HFpEF trials.7,30,32 At least moderate pulmonary hypertension, defined as a peak TR velocity of ≥3.5 m/sec, was present in 8%. Concordant with data from the Olmsted County cohort, estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure was significantly associated with E/E’ ratio as an index of LV filling pressure.20 Prior studies, however, have not assessed PVR in HFpEF. In the smaller subgroup of our participants in whom PVR could be estimated non-invasively, PVR was elevated in approximately 11%. Relatively little is also known about RV performance in HFpEF. Gross RV dysfunction, based on the FAC, was uncommon. However, while guideline documents define abnormal RV FAC as <0.35,17 studies in HF with reduced EF have demonstrated the prognostic relevance of RVFAC <0.40,37 which was present in 11% of participants.

Limited data exists regarding the prevalence and prognostic implication of valvular disease in HFpEF. Most clinical trials and observational studies have excluded individuals with significant mitral or aortic valve disease from HFpEF studies. Of 619 HFpEF patients in the New York Heart Failure Registry, moderate-to-severe or greater degrees of MR was present in 10%.25 Similarly, in the Northwestern HFpEF Registry, moderate mitral regurgitation was noted in approximately 14% of patients.27 Consistent with these findings, moderate or greater MR was noted in 12% of TOPCAT participants. Although hemodynamically significant valvular disease was an exclusion criterion, interobserver agreement for MR grading is known to be approximately 83%, possibly explaining the discordance between site and corelab assessments in these cases.38 Consistent with TOPCAT trial inclusion criteria, no cases of severe mitral stenosis, aortic regurgitation, or aortic stenosis were detected.

Several limitations of this analysis should be noted. Although centrally analyzed, a portion of the echocardiograms included in this analysis were clinical echocardiograms not obtained by a prespecified protocol, and could have been performed within 6 months of randomization which may introduce variability into measurements. Because of this, certain echocardiographic views or measures, particularly Doppler measures, were missing in a large proportion of patients. In addition, although the study protocol precluded intercurrent myocardial infarction, we cannot exclude that cardiac structure and function may have changed for other reasons during this period. Compared to TOPCAT participants not included in the echo study, those included differed in some baseline characteristics which, although relatively minor, may limit the generalizability of these findings. Finally, clinical trials by necessity impose inclusion and exclusion criteria, and therefore these findings may not be generalizable to community-based cohorts.

Conclusions

Echocardiographic findings from the 935 participants enrolled in TOPCAT demonstrate a high prevalence of concentric LV remodeling and hypertrophy, LA enlargement, and pulmonary hypertension. In the context of existing epidemiologic and clinical trial studies, these findings suggest that the TOPCAT participants represent a particularly high risk group within the HFpEF syndrome. Similar to other published HFpEF trials, diastolic function was normal in approximately one-third, highlighting the heterogeneity of the cardiac phenotype in this syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source:

TOPCAT was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Bethesda, MD grant N01 HC45207. The work for this manuscript was also supported by NHLBI grant 1K08HL116792-01A1 (A.M.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu P. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJV, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J for the CHARM investigators and committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleland JGF, Tendera M, Adamus J, Freemantle N, Polonski L, Taylor J on behalf of PEP-CHF investigators. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Anderson S, Donovan M, Iverson E, Staiger C, Ptaszynska A for the I-PRESERVE investigators. New Engl J Med. 2008;359:2456–2467. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah AM, Pfeffer MA. The many faces of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:555–556. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zile MR, Gottdiener JS, Hetzel SJ, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Baicu CF, Massie BM, Carson PE. Prevalence and significance of alterations in cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2011;124:2491–2501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam CSP, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Bursi F, Borlaug BA, Ommen SR, Kass DA, Redfield MM. Cardiac structure and ventricular-vascular function in persons with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation. 2007;115:1982–1990. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Persson H, Lonn E, Edner M, Baruch L, Lang CC, Morton JJ, Ostergren J, McKelvie RS. Diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved systolic function: need for objective evidence: results from the CHARM Echocardiographic Substudy – CHARMES. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai AS, Lewis EF, Li R, Solomon SD, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Clausell N, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, McKinlay S, O’Meara E, Shaburishvili T, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA. Rationale and design of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist Trial: A randomized, controlled study of spironolactone in patients with symptomatic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2011;162:966–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah SJ, Heitner JF, Sweitzer NK, Anand IS, Kim HY, Harty B, Boineau R, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Lewis EF, Markov V, O’Meara E, Kobulia B, Shaburishvili T, Solomon SD, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Li R. Baseline characteristics of patients in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:184–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.972794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teicholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic-angiographic correlation in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ Chamber Quantification Writing Group. American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CG, Thomas JD, Anconina J, Harrigan P, Mueller L, Picard MH, Levine RA, Weyman AE. Impact of impinging wall jet on color Doppler quantification of mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 1991;84:712–720. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, Waggoner AD, Flachskampf FA, Pellikka PA, Evangelista A. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:107–133. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbas AE, Fortuin D, Schiller NB, Appleton CP, Moreno CA, Lester SJ. A simple method for noninvasive estimation of pulmonary vascular resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:777–802. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam CSP, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Borlaug BA, Enders FT, Redfield MM. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurer MS, Burkhoff D, Fried LP, Gottdiener J, King DL, Kitzman DW. Ventricular structure and function in hypertensive participants with heart failure and a normal ejection fraction: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:972–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Liu JE, Welty TK, Lee E, Rodeheffer R, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV. Congestive heart failure despite normal left ventricular systolic function in a population-based sample: The Strong Heart Study. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1090–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He KL, Burkhoff D, Leng WX, Liang ZR, Fan L, Wang J, Maurer MS. Comparison of ventricular structure and function in Chinese patients with heart failure and ejection fractions >55% versus 40% to 55% versus<40% Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta DK, Shah AM, Castagno D, Takeuchi M, Loehr LR, Fox ER, Butler KR, Mosley TH, Kitzman DW, Solomon SD. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in African Americans: the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2013;1:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klapholz M, Maurer M, Lowe AM, Messineo F, Meisner JS, Mitchell J, Kalman J, Phillips RA, Steingart R, Brown EJ, Berkowitz R, Moskowitz R, Soni A, Mancini D, Bijou R, Sehhat K, Varshneya N, Kukin M, Katz SD, Sleeper LA, Le Jemtel TH. Hospitalization for heart failure in the presence of a normal left ventricular ejection fraction: Results of the New York Heart Failure Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1432–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Mahjoub H, Souliere V, Levy F, Peltier M, Slama M, Massy Z. Prognosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A 5 year prospective population-based study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:339–347. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz DH, Beussink L, Sauer AJ, Freed BH, Burke MA, Shah SJ. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes associated with eccentric versus concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kizer JR, Arnett DK, Bella JN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Province MA, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Liu JE, Devereux Differences in left ventricular structure between black and white hypertensive adults: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. Hypertension. 2004;43:1182–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128738.94190.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drazner MH, Dries DL, Peshock RM, Cooper RS, Klassen C, Kazi F, Willett D, Victor RG. Left ventricular hypertrophy is more prevalent in blacks than whites in the general population: the Dallas Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005;46:124–129. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000169972.96201.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, Voors A, Shah A, Kraigher-Krainer E, Shi V, Bransford T, Takeuchi M, Gong J, Lefkowitz M, Packer M, McMurray JJV. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A phase II randomized-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1387–1395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, Kraigher-Krainer E, Colantonio C, Kamke W, Duvinage A, Stahrenberg R, Durstewitz K, Loffler M, Dungen HD, Tschope C, Herrmann-Lingen C, Halle M, Hasenfuss G, Gelbrich G, Pieske B. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The ALDO-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;209:781–791. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, Semigran MJ, Lee KL, Lewis G, LeWinter MM, Rouleau JL, Bull DA, Mann DL, Deswal A, Stevenson LW, Givertz MM, Ofili EO, O’Connor CM, Felker GM, Goldsmith SR, Bart BA, McNulty SE, Ibarra JC, Lin G, Oh JK, Patel MR, Kim RJ, Tracy RP, Velazquez EJ, Anstrom KJ, Hernandez AF, Mascette AM, Braunwald E. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1268–1277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure – abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1953–1959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westermann D, Kasner M, Steendijk P, Spillman F, Riad A, Weitmann K, Hoffmann W, Poller W, Pauschinger M, Schultheiss H-P, Tschope C. Role of left ventricular stiffness in heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circulation. 2008;117:2051–2060. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalen H, Thorstensen A, Vatten LJ, Aase SA, Stoylen A. Reference values and distribution of conventional echocardiographic Doppler measures and longitudinal tissue Doppler velocities in a population free from cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:6114–6622. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.926022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chahal NS, Lim TK, Jain P, Chambers JC, Kooner JS, Senior R. Normative reference values for the tissue Doppler imaging parameters of left ventricular function: a population-based study. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:51–56. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anavekar NS, Skali H, Bourgoun M, Ghali JK, Kober L, Maggioni AP, McMurray JJV, Velazquez E, Califf R, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Usefulness of right ventricular fractional area change to predict death, heart failure, and stroke following myocardial infarction (from the VALIANT ECHO Study) Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dall’Aglio V, D’Angelo G, Moro E, Nicolosi GL, Burelli C, Zardo F, Cervesato E, Zanuttini D. Interobserver and echo-angio variability of two-dimensional colour Doppler evaluation of aortic and mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:334–340. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]