Abstract

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is typically associated with minimal inflammation; however, patients may develop an inflammatory response due to immune reconstitution (IRIS). The authors aimed to determine if characteristics and outcomes of PML are altered in those with IRIS. A retrospective records review was performed on 87 patients diagnosed with PML at Johns Hopkins, 27 of which had a syndrome consistent with IRIS. Gadolinium enhancement on MRI occurred in 44.4% of cases of PML-IRIS versus 5.1% in PML (p<0.05), and thus had low diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. In HIV+ cases, CD4 counts were lower in those who later developed IRIS (mean 34.8 vs. 71.7, p<0.05) and was predictive of the development of IRIS (p<0.05). Improved prognosis was seen with higher cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white blood cell counts and protein levels, but not for gadolinium enhancement and there were no differences in survival for PML versus PML-IRIS.

Keywords: Leukoencephalopathy, Progressive multifocal, Immune reconstitution inflammatory, syndrome, Immunosuppression, HIV

1. Introduction

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a rare viral infection of the central nervous system that is caused by the JC virus (Padgett et al., 1971). PML usually develops in immunocompromised states, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), organ transplantation, hematological malignancies, and immunosuppressive therapies (Brooks and Walker, 1984).

Nearly universally fatal in the setting of HIV infection in the past (Holman et al., 1991; Holman et al., 1998), the advent of combination anti-retroviral therapy (cART) has increased the survival of those with PML to approximately 50% (Clifford et al., 1999; Antinori et al., 2001; Cinque et al., 2003). Occasionally, despite cART, individuals with HIV-related PML will continue to clinically decline despite restoration of their immune system – in which case a diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is considered.

CNS-IRIS is a clinical manifestation of rapid influx of immune cells into the central nervous system at the time of immune restoration (Rushing et al., 2008). Associated risk factors are HIV-infection, preexisting opportunistic infection, being cART naïve, having a low nadir CD4 count prior to cART, and achieving a substantial decline in HIV viral load after instituting cART (Shelburne et al., 2005; Manabe et al., 2007; Dhasmana et al., 2008). As much as 23% of HIV-infected patients with PML who recently started cART will develop PML-IRIS (Cinque et al., 2001; Falco et al., 2008). PML-IRIS has also occurred in non-HIV cases of PML, such as in multiple sclerosis after removal of natalizumab by plasma exchange (Clifford et al., 2010). PML-IRIS needs to be recognized early as this syndrome can result in death or permanent neurological disability (Tan et al., 2009). The diagnosis of CNS-IRIS can be challenging as currently there are no established diagnostic criteria (Johnson and Nath, 2010). In this study we characterized the differences between PML and PML-IRIS based on clinical, imaging, and laboratory data to elucidate specific predictors of conversion to IRIS and overall prognosis.

2. Methods

This study consisted of a retrospective review of medical records. Permission to perform this review was granted by the institutional review board of Johns Hopkins University. Candidate subjects for analysis were identified by two means. First, patients were identified through a clinical database of patients diagnosed with PML and followed in the Moore Clinic for care of patients with HIV infection at Johns Hopkins Hospital between 1992 and 2008. Additionally, a hospital billing database search was performed (also at Johns Hopkins Hospital) for the corresponding ICD-9 code for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, which identified candidate cases diagnosed in the years 2000 through 2008. One hundred and fifty six candidates were identified via this search. For the purposes of this review, the diagnosis of PML was defined by identical means to our prior report (Tan et al., 2009): by detection of the JC virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or biopsy tissue, characteristic pathologic appearance in brain biopsy tissue, or by the presence of characteristic clinical and neuroradiologic features with exclusion of other opportunistic infections. After an initial review of medical records, laboratory results, and imaging, we found that 47 cases had been mislabeled and did not meet the criteria for diagnosis of PML. Another 22 cases were removed from analysis due to lack of adequate medical records and/or neuroimaging studies available for review. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected via review of each individual case's available records. Review of archived MRI images was performed by the authors D.H. and S.N. For the PML group, scans at the time of PML diagnosis were used. For the PML-IRIS group, scans at the time of IRIS diagnosis were used.

To identify cases with a dual syndrome of PML-IRIS, we developed an a priori clinical definition for this syndrome. Cases were categorized as having PML-IRIS if they met the following clinical definition: a rapid (days to weeks) deterioration in neurological status occurring in temporal association with laboratory evidence of reconstitution of the immune system. For HIV cases, a minimum of a 100% increase in the CD4 T-cell count in those with sizeable declines in the HIV viral load was considered as evidence of immune reconstitution. For non-HIV cases, evidence of immune reconstitution was based on the relevant laboratory parameters for the individual's particular immunosuppressive agent. Cases were further split based on timing of the onset of IRIS. Those that developed IRIS sometime after having been diagnosed with PML were labeled as delayed PML-IRIS (PML-d-IRIS) and those that developed symptoms of PML and IRIS at the same time were labeled as simultaneous PML-IRIS (PML-s-IRIS).

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 10.1 IC software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). A difference in group means and proportions for demographic, clinical, radiologic, and laboratory data was analyzed by Student's t-test. The ability of demographic, clinical, radiologic, or laboratory data at the time of PML diagnosis to predict later development of IRIS was tested by simple logistic regression and reported as odds ratios. Those with PML-s-IRIS were removed from this portion of the analysis. It should be noted that radiologic information for this portion of the analysis was taken from scans at the time of IRIS in those that developed IRIS, but it is presumed that the location of the T2/FLAIR portion of the PML lesions should have been approximately the same at the time of PML diagnosis. The ability of each individual risk factor to predict clinical prognosis was tested by Cox regression and hazard ratios were determined. The proportional hazards assumption for this regression was tested by visual inspection of log–log plots. Kaplan–Meier curves were also analyzed to inspect survival differences for dichotomous predictive variables, with statistical significance determined by log-rank testing. For the survival and regression analyses, any parameters attaining statistical significance at the p<0.05 were re-tested via 1000 bootstrap resamplings of the data to confirm statistical significance. This was performed to reduce the family-wise error rate due to multiple comparisons. All survival analyses (Cox and Kaplan–Meier) were conducted with the time from PML symptom onset to last known data point as the time variable. For determination of prognosis, survival failure was set as either severe disability or death (combined outcome described as “poor prognosis” hereafter) at last known follow up. Severe disability was defined as cases with complete impairment of activities of daily living, bed-bound status, and severely limited or no communicative ability. The majority of such cases were noted to be discharged to hospice care at last known follow up, so it was assumed that mortality followed shortly thereafter. A separate analysis was conducted for those in whom the date of death was known.

3. Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the population studied are listed in Table 1. As expected, the majority of cases identified (79 of 87) had PML in the setting of HIV infection. However, 8 non-HIV cases were also identified. The only difference noted between the PML and PML-IRIS groups was the proportion having received medical treatment aimed at suppressing the JC virus (such as interferon-alpha, mefloquine, etc.), which was significantly greater in the PML-IRIS group. For those that developed IRIS, the mean time from beginning cART or removal of immunosuppressive medications to IRIS onset was 39.9 days. Only 4 cases received corticosteroid treatment for their IRIS-related syndrome.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient population studied.

| Characteristic | PML group, n=60 | PML-IRIS group, n=27 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age at PML diagnosis (SD) | 43.5 (10.4) | 43.0 (9.1) |

| Males (%) | 46 (77%) | 20 (74%) |

| HIV+ (%) | 55 (92%) | 24 (89%) |

| Non-HIV diagnoses (n) | Lymphoma (3), leukemia (1), Liver transplant (1) | Systemic lupus (1), lung transplant (1), unknown immunosuppression (1) |

| Medical treatment for PML (%) | 17 (28%)* | 15 (56%)* |

| JC positive CSF (%) | 19 (56%) | 14 (61%) |

| Biopsy diagnosis | 7 | 3 |

| Mean time from HIV diagnosis or immunosuppression to PML (SD) | 6.54 years (6.52) | 7.06 years (7.02) |

| Mean time from cART or removal of immunosuppression to IRIS (SD) | 39.9 days (31.0) | |

| Cases with PML and IRIS onset simultaneously (PML-S-IRIS) (%) | 8 (30%) | |

| Cases with IRIS development after PML onset (PML-D-IRIS) (%) | 19 (70%) | |

| Cases receiving corticosteroid treatment for IRIS (%) | 4 (15%) |

Differences between group means/proportions were tested via Student's t-test Group differences significant at p<0.05 are marked with.

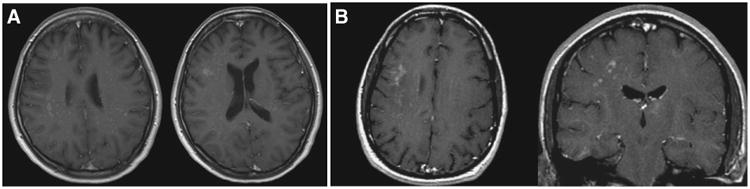

The differences between each group's MRI characteristics were reviewed (Table 2). Involvement of the temporal lobes was present in a higher proportion of PML-IRIS cases (44.4% versus 21.7%, p<0.05). Gadolinium enhancement occurred in 44.4% of PML-IRIS cases, and only in 5.1% of PML cases (p<0.05). All cases of enhancement in PML-IRIS were in a patchy, nodular pattern in the area of known PML lesions (seen on corresponding T2/FLAIR images). An example of this enhancement pattern is seen in Fig. 1. Of the three instances of contrast enhancement in PML cases, none were patchy or nodular. Gadolinium enhancement was more common in those with IRIS (Odds Ratio 14.93 (3.73–59.81)) and those with parietal (Odds Ratio 4.61 (95% CI: 1.20–17.74)) and occipital (Odds Ratio 7.38 (95% CI: 2.21–24.61)) lesions, but did not correlate with any laboratory parameters or other demographic or clinical characteristics (see Table e-1 for data).

Table 2.

MRI characteristics of cases of PML versus PML-IRIS.

| MRI finding | PML group | PML-IRISgroup |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal lobe involvement (%) | 41 (68.3) | 21 (77.8) |

| Parietal lobe involvement (%) | 29 (48.3) | 17 (63.0) |

| Temporal lobe involvement (%) | 13 (21.7) | 12 (44.4)* |

| Occipital lobe involvement (%) | 11 (18.3) | 10 (37.0) |

| Brainstem involvement (%) | 36 (60.0) | 16 (59.3) |

| Cerebellar involvement (%) | 26 (43.3) | 7 (25.9) |

| Corpus callosum involvement (%) | 17 (28.8) | 9 (33.3) |

| Deep gray nuclei involvement (%) | 21 (35.6) | 9 (33.3) |

| U-fiber involvement (%) | 23 (59.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Edema/mass effect (%) | 4 (7.1) | 2 (7.4) |

| T1 hypointensity (%) | 34 (91.9) | 16 (94.1) |

| Gadolinium enhancement (%) | 3 (5.1) | 12 (44.4)* |

| Enhancement pattern (n, %) | Peripheral enhancement (1, 33.3), Central enhancement (2, 66.6) | Nodular (12, 100) |

Comparison between groups was made via Student's t-test of proportions. Group differences with p value <0.05 marked with.

Note that gadolinium enhancement is the main distinguishing characteristic between the two groups, but it is not universally present in all PML-IRIS cases.

Fig. 1.

Examples of contrast enhancement in PML-IRIS. A: Axial post-contrast T1 images from a 38 year old woman post lung transplant. B: Axial and coronal post-contrast T1 images from a 39 year old man with HIV.

A comparison of laboratory values between the two groups, and within the PML-IRIS group (before IRIS versus during IRIS) appears in Table 3. In cases of PML due to HIV infection, the CD4 cell count at time of diagnosis of PML was significantly lower in individuals that subsequently developed IRIS compared to those that did not develop IRIS. Consistent with our clinical definition, amongst HIV+ cases, there were substantial drops in HIV viral load and corresponding increases in CD4 cells between the time of PML diagnosis and the onset of IRIS in the PML-IRIS group.

Table 3.

Laboratory values at time of diagnosis of PML and PML-IRIS.

| Lab finding | PML group | PML-IRIS group | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| At PML diagnosis | At IRIS diagnosis | ||

| CSF WBC (cells/mm3) | 7.54 (15.96) | 1.93 (5.25) | 3.06 (2.67) |

| CSF protein (mg/dL) | 54.0 (31.2) | 44.9 (26.0) | 55.0 (22.4) |

| CSF glucose (mg/dL) | 56.8 (12.0) | 59.3 (13.9) | 60.4 (13.7) |

| HIV CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 71.7 (72.4) | 34.8 (48.2)* | 110.6 (86.6)† |

| HIV viral load (copies/mL) | 251,373 (418,348) | 251,691 (212,583) | 5757 (13,017)* † |

| Peripheral WBC (cells/mm3) | 4.28 (2.44) | 4.54 (3.56) | 5.30 (3.33) |

Laboratory values are given as mean values with standard deviation in parentheses. Comparison between groups was made via Student's t-test (unpaired).

Signifies p value<0.05 for comparison to PML group at time of PML diagnosis.

signifies p<0.05 for comparison to PML-IRIS group at time of PML diagnosis. PML-s-IRIS cases were removed for the within PML-IRIS group comparison.

The use of pharmacological treatment for PML and baseline CD4 counts of <50 cells/mm3 significantly increased the odds for development of IRIS (Table 4). CSF White blood cell count (WBC)>10 cells/mm3 and CSF protein levels of >40 mg/dL were associated with reduced hazards of poor prognosis (Table 4, hazard ratios). A similar non-significant trend was also noted for prediction of death. Of the 61 patients with CSF available for review, 9 patients had WBC>10 cells/mm3 and 31 had protein of >40 mg/dL. Eight patients had both. The presence of a parietal lobe lesion also conveyed a reduced hazard of poor prognosis, but not death.

Table 4.

Risk factors for development of IRIS and for prognosis/survival amongst all cases.

| Risk factor | Risk of development of IRIS | Risk of poor prognosis† after diagnosis of PML | Risk of death after diagnosis of PML | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (10 year increments) | 0.82 (0.48, 1.40) | 0.465 | 0.83 (0.59, 1.17) | 0.296 | 0.89 (0.52, 1.52) | 0.657 |

| Female gender | 1.92 (0.63, 5.80) | 0.250 | 1.49 (0.76, 2.94) | 0.244 | 1.63 (0.56, 4.70) | 0.370 |

| HIV diagnosis | 0.48 (0.10, 2.30) | 0.356 | 0.64 (0.25, 1.65) | 0.355 | 0.41 (0.12, 1.46) | 0.170 |

| Medical treatment for PML | 7.08 (2.21, 22.71) | 0.001* | 1.06 (0.58, 1.96) | 0.845 | 1.93 (0.73, 5.12) | 0.188 |

| CSF WBC>10 cells/mm3 | 0.53 (0.18, 1.57) | 0.251 | 0.40 (0.21, 0.77) | 0.006* | 0.79 (0.29, 2.12) | 0.638 |

| CSF protein>40 mg/dL | 0.30 (0.07, 1.28) | 0.104 | 0.36 (0.19, 0.68) | 0.002* | 0.55 (0.17, 1.75) | 0.313 |

| CD4 count<50 cells/mm3 | 3.25 (1.09, 9.73) | 0.035* | 1.61 (0.88, 2.96) | 0.124 | 0.83 (0.32, 2.19) | 0.706 |

| HIV viral load>100,000 copies/mL | 1.36 (0.39, 4.72) | 0.625 | 1.17 (0.57, 2.38) | 0.668 | 1.09 (0.35, 3.39) | 0.880 |

| Frontal lesion | 1.74 (0.51, 5.94) | 0.378 | 1.38 (0.69, 2.74) | 0.358 | 1.57 (0.51, 4.84) | 0.433 |

| Parietal lesion | 1.83 (0.63, 5.29) | 0.263 | 0.52 (0.28, 0.96) | 0.036* | 1.03 (0.39, 2.73) | 0.951 |

| Temporal lesion | 2.11 (0.69, 6.43) | 0.190 | 0.95 (0.49, 1.90) | 0.880 | 0.81 (0.26, 2.53) | 0.721 |

| Occipital lesion | 1.59 (0.47, 5.35) | 0.453 | 0.66 (0.33, 1.35) | 0.255 | 1.17 (0.43, 3.20) | 0.753 |

| Brainstem lesion | 1.44 (0.48, 4.32) | 0.948 | 1.56 (0.83, 2.94) | 0.168 | 1.23 (0.46, 3.29) | 0.674 |

| Corpus callosum lesion | 1.44 (0.48, 4.28) | 0.511 | 0.75 (0.38, 1.49) | 0.409 | 0.67 (0.22, 2.07) | 0.491 |

| 3 or more of above regions involved | 1.16 (0.39, 3.52) | 0.784 | 1.23 (0.64, 2.35) | 0.541 | 0.97 (0.36, 2.64) | 0.955 |

| Gadolinium enhancement | – | – | 0.62 (0.26, 1.48) | 0.282 | 1.26 (0.40, 3.91) | 0.691 |

| Diagnosis of IRIS | – | – | 1.20 (0.64, 2.22) | 0.575 | 2.40 (0.92, 6.25) | 0.074 |

| PML-s-IRIS | – | – | 0.47 (0.15, 1.53) | 0.211 | 1.40 (0.40, 4.91) | 0.602 |

Odds ratio calculated by simple logistic regression for risk of development of IRIS based on risk factor at time of PML diagnosis (except for lesion location, which in IRIS cases only was taken from the T2/FLAIR portion of the scan at the time of IRIS). Those that developed PML and IRIS symptoms with simultaneous onset (PML-s-IRIS) were not included in this analysis. Results with p<0.05 are listed in bold. Hazard ratio calculated by Cox regression for risk of development of poor prognosis or death based on risk factor at time of PML diagnosis. All individuals were included in this analysis. Results that attained statistical significance at p<0.05 are listed in bold.

p<0.05 for confirmation of statistical significance via 1000 bootstrap replications.

“poor prognosis” defined as either severe disability or death at the time of last known follow up.

Gadolinium enhancement was not a significant predictor of poor prognosis or death. Although the median survival time for the PML-IRIS group was reduced in comparison to the PML group (0.53 versus 2.39 years, respectively), this difference was not significant (visually displayed in Fig. 2). Simultaneous versus delayed onset IRIS also did not convey any contribution to prediction of outcomes.

Fig. 2.

A: Survival difference between PML and PML-IRIS group. B: Survival difference between those with (+) and without (−) gadolinium enhancement on MRI.C: Survival based on white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid at time of PML diagnosis. D: Survival based on protein level in the cerebrospinal fluid at time of PML diagnosis. P values for log rank test for difference in survival. † “poor prognosis” defined as either severe disability or death at the time of last known follow up.

In a repeat analysis amongst HIV cases only (Table e-2), the same predictors of IRIS and prognosis were found. Additionally, elevated CSF protein showed reduced odds for development of IRIS (p<0.049) and there was a non-significant trend towards increased hazards of death in HIV patients with IRIS.

When Cox regression analysis was performed for the PML-IRIS cases only, none of the tested risk factors predicted survival (Table e-3). As only 4 patients were treated with corticosteroids, we were unable to determine if such treatment impacted survival.

4. Discussion

The diagnosis of PML has become easier with improved detection of JC virus in CSF; however, diagnosing PML-IRIS remains a challenge as there is no agreed upon criteria or specific biomarkers. In the absence of biomarkers, a clinical definition of IRIS is used, which consists of a paradoxical deterioration in an individual's clinical status during restoration of their immune system. A potential drawback of this definition is that it can lead to over-diagnosis of IRIS because some individuals may deteriorate as a result of progression of their underlying infection and not IRIS. To avoid misdiagnoses, a proposed set of criteria for diagnosing IRIS were developed so that this syndrome could be more accurately diagnosed (Shelburne et al., 2006). These criteria have specific inclusion requirements including being HIV positive, receiving cART associated with a decrease in HIV viral load and a corresponding increase in CD4 T-cell counts, having symptoms suggestive of an inflammatory or infectious process without a specific agent found, and individuals should have a clinical course that could not be explained by any existing infection. These criteria are not universally agreed upon, however, and are not broad enough to allow for inclusion of cases of IRIS that occur in patients who are not infected with HIV. Therefore, we sought out to better characterize the differences between PML and PML-IRIS, independent of HIV status, in hopes to identify additional clinical, laboratory, or radiographic markers that may help in facilitating the diagnosis of IRIS and determine if there are specific predictors of prognosis.

The major discriminating factor between those with PML and those with PML-IRIS found in this study was the presence or absence of gadolinium enhancement on MRI. This finding, representing breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, may reflect the rapid influx of cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells directed at JC virus infected cells seen pathologically (Vendrely et al., 2005; Rushing et al., 2008; McCombe et al., 2009). The source of the predominantly nodular pattern specifically seen in the PML-IRIS cases may be the clustering of inflammation around local microvasculature (Vendrely et al., 2005; Rushing et al., 2008). Although enhancement was seen in many cases, it was perhaps surprisingly not seen in the majority of cases of PML-IRIS in this series. Additionally, a small percentage of cases of PML that did not meet the clinical definition of PML-IRIS (thus did not have signs of immune reconstitution by laboratory studies or did not have paradoxical clinical worsening) also had gadolinium enhancement, and thus this could not be said to be sensitive or specific for detection of the presence of IRIS. Although this phenomenon has been reported in previous evaluations of MRI in PML (Post et al., 1999), it is unclear if there is an alternate reason for contrast enhancement in these cases, such as direct disruption of the blood brain barrier in the setting of infection, or if this represents subclinical or asymptomatic IRIS. Our findings may provide clinical support for findings of Huang et al. (2007) in which pathologic evidence of inflammation was found in PML lesions that were both contrast enhancing and not contrast enhancing. If non-enhancing inflammatory lesions can occur, then clearly the presence of enhancement is not highly sensitive to the inflammatory reaction to JC virus by the reconstituted immune system. As the level of CD3+ T-cell infiltration into PML lesions correlates with the likelihood of contrast enhancement of that lesion (Huang et al., 2007), it is likely that inflammatory reactions to PML occur on a gradient of severity, with the degree of inflammation and also likely the size and location of a lesion adding up to the risk of a clinical IRIS syndrome.

Requiring gadolinium enhancement as part of the definition of the PML-IRIS syndrome would result in exclusion of cases with moderate, but clinically significant inflammatory reactions to PML. For this reason, we would propose more widespread adoption of our broader clinical definition (Table 5) for future clinical studies of PML-IRIS, including therapeutic intervention trials.

Table 5.

Diagnostic criteria for PML-IRIS.

| Required |

|

| Supportive, but not required | Patchy, nodular enhancement within PML lesions on gadolinium enhanced T1 MRI |

The lack of enhancement in 56% of PML-IRIS cases in this series could also possibly be due to the timing of the scans performed, which was not standardized in our study given its retrospective nature. The phenomenon of enhancement could possibly be transient in nature, and thus a prospective study involving imaging at regular intervals in those at risk for PML-IRIS might provide more accurate data. Enhancement may also be location-dependent, as evidenced by the significantly increased odds of gadolinium enhancement for PML lesions found in the parietal and occipital white matter, which could possibly be due to anterior–posterior differences in cytokine induced blood–brain barrier permeability (Wong et al., 2004; Thachil, 2010).

The increased odds of developing IRIS in individuals with HIV infection and CD4 cell counts of <50 cells/mm3 prior to initiating cART is consistent with prior studies (Manabe et al., 2007; Falco et al., 2008). This could be due to the rapidity of immune reconstitution in those who are more severely immunosuppressed compared to those who are not; or perhaps due to more extensive opportunistic infection in these individuals. The finding of increased risk of IRIS in individuals receiving treatments aimed at the JC virus has not been previously described. This finding could signify a pro-inflammatory state promoted by these agents, or may represent a biased sample, as those who received these treatments may have had other common characteristics at presentation that lead to treatment. Knowledge of these risk factors, in addition to the typical timing of onset of PML-IRIS (approximately 40 days from initiation of cART or removal of immunosuppression in our study, similar to others (McCombe et al., 2009; Clifford et al., 2010)) could lead to better risk stratification, treatment considerations, and future targeted studies. Spinal fluid parameters or peripheral WBC count did not help to discriminate between those with and without IRIS in this study.

There was no significant improvement in the prognosis of PML in this cohort based on the presence or absence of IRIS, which is consistent with prior data (Falco et al., 2008). We found no specific predictors of survival in those with PML-IRIS, including simultaneous versus delayed onset and gadolinium enhancement, but this may have been limited by a relatively small sample size. We thus were unable to support previous suggestions that those with gadolinium enhancement have improved survival (Berger et al., 1998a, 1998b; Thurnher et al., 2001). In addition to a more favorable prognosis for those with parietal lobe lesions (perhaps due to less life-impairing deficits in this location), we interestingly found that a favorable PML outcome was predicted by increased WBC and protein in CSF at the time of PML diagnosis. In our review of prior large studies on those with PML failed to find analysis of the predictive nature of CSF parameters (Berger et al., 1998a, 1998b; Antinori et al., 2001; Falco et al., 2008; Engsig et al., 2009), and thus this is a novel finding in our study. Elevation in these markers perhaps indicates that improved prognosis occurs with a more robust initial inflammatory response to the JC virus infection, which has been implied by previous studies demonstrating evidence of inflammation on MRI or histopathology (Berger et al., 1998a, 1998b). These findings might call into question the notion of the use of corticosteroids in those with IRIS (Martinez et al., 2006), as this would limit the inflammatory response to the JC virus in those treated. Such treatment decisions would have to, of course, be weighed with the possibility of excessive inflammatory responses, as demonstrated by the successful use of steroids in prior studies in patients with impending herniation syndromes or other severe clinical manifestations of IRIS (Martinez et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2009). In fact, the lack of improved survival seen in PML-IRIS in our study, despite improved survival in those with signs of CSF inflammation at the time of PML diagnosis, might represent the negative impact of over-exuberant inflammation in a portion of IRIS cases. This might explain the non-significant trend for greater hazards of death in PML-IRIS cases, seen best in the HIV cases only.

Unfortunately, given that only four patients in this study were treated with corticosteroids, we were unable to elucidate treatment effects from our data. Prospective studies should be performed in the future to determine the impact of corticosteroid use on the survival of those with PML-IRIS.

Although this study is limited by the retrospective nature of our data and the lack of a true gold standard for PML-IRIS diagnosis, the findings within are worth noting and propel further scientific questions. Given the increased interest in PML in the neurological community due to the presence of this syndrome in those treated with monoclonal antibodies for multiple sclerosis and rheumatologic disease (Carson et al., 2009; Linda et al., 2009), this is a timely report that may help to guide prediction of and prognostication in those with PML-IRIS, and may inform the design of future prospective studies, which will be needed to help determine the effects of treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the involvement of Peter Dziedicz, Deneen Esposito, Agnes King, Jason Creighton, and Ned Sacktor in the clinical care of many of the patients reviewed in this study.

Footnotes

Statistical analysis performed by: Daniel M. Harrison, MD, with guidance by Richard L. Skolasky, Sc.D.

Study sponsorship: Supported in part by grant R01NS056884 from the NIH to AN and grants 1P30MH075673 and NS44807 from the NIH to JCM.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10. 1016/j.jneuroim.2011.07.003.

References

- Antinori A, Ammassari A, et al. Epidemiology and prognosis of AIDS-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the HAART era. J Neurovirol. 2001;7(4):323–328. doi: 10.1080/13550280152537184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JR, Levy RM, et al. Predictive factors for prolonged survival in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 1998a;44(3):341–349. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JR, Pall L, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with HIV infection. J Neurovirol. 1998b;4(1):59–68. doi: 10.3109/13550289809113482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Walker DL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurol Clin. 1984;2(2):299–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson KR, Evens AM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after rituximab therapy in HIV-negative patients: a report of 57 cases from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports project. Blood. 2009;113(20):4834–4840. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinque P, Pierotti C, et al. The good and evil of HAART in HIV-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurovirol. 2001;7(4):358–363. doi: 10.1080/13550280152537247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinque P, Bossolasco S, et al. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy-induced immune reconstitution on development and outcome of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: study of 43 cases with review of the literature. J Neurovirol. 2003;9(Suppl 1):73–80. doi: 10.1080/13550280390195351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford DB, Yiannoutsos C, et al. HAART improves prognosis in HIV-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52(3):623–625. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford DB, De Luca A, et al. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: lessons from 28 cases. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):438–446. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhasmana DJ, Dheda K, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Drugs. 2008;68(2):191–208. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engsig FN, Hansen AB, et al. Incidence, clinical presentation, and outcome of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in HIV-infected patients during the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: a nationwide cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(1):77–83. doi: 10.1086/595299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco V, Olmo M, et al. Influence of HAART on the clinical course of HIV-1-infected patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: results of an observational multicenter study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):26–31. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817bec64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman RC, Janssen RS, et al. Epidemiology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the United States: analysis of national mortality and AIDS surveillance data. Neurology. 1991;41(11):1733–1736. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.11.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman RC, Torok TJ, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the United States, 1979–1994: increased mortality associated with HIV infection. Neuroepidemiology. 1998;17(6):303–309. doi: 10.1159/000026184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Cossoy M, et al. Inflammatory progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(1):34–39. doi: 10.1002/ana.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T, Nath A. Neurological complications of immune reconstitution in HIV-infected populations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:106–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linda H, von Heijne A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1081–1087. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe YC, Campbell JD, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: risk factors and treatment implications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(4):456–462. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181594c8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JV, Mazziotti JV, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with PML in AIDS: a treatable disorder. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1692–1694. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242728.26433.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombe JA, Auer RN, et al. Neurologic immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV/AIDS: outcome and epidemiology. Neurology. 2009;72(9):835–841. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343854.80344.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett BL, Walker DL, et al. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. Lancet. 1971;1(7712):1257–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post MJ, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in AIDS: are there any MR findings useful to patient management and predictive of patient survival? AIDS Clinical Trials Group, 243 Team. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(10):1896–1906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushing EJ, Liappis A, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome of the brain: case illustrations of a challenging entity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(8):819–827. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318181b4da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelburne SA, Visnegarwala F, et al. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2005;19(4):399–406. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161769.06158.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelburne SA, Montes M, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: more answers, more questions. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57(2):167–170. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Roda R, et al. PML-IRIS in patients with HIV infection: clinical manifestations and treatment with steroids. Neurology. 2009;72(17):1458–1464. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343510.08643.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thachil J. A clue to the pathophysiology of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(12):1536–1537. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.315. 1536; author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurnher MM, Post MJ, et al. Initial and follow-up MR imaging findings in AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(5):977–984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrely A, Bienvenu B, et al. Fulminant inflammatory leukoencephalopathy associated with HAART-induced immune restoration in AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109(4):449–455. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0983-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D, Dorovini-Zis K, et al. Cytokines, nitric oxide, and cGMP modulate the permeability of an in vitro model of the human blood–brain barrier. Exp Neurol. 2004;190(2):446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.