Healthcare professionals are confronted with patients’ emotional traumas such as grief, anger, and loneliness on a daily, if not hourly, basis. Faced with this kind of distress, we might exhibit (and experience) what I will call ‘true empathy.’ This kind of empathy involves feeling another’s emotions oneself as an ‘emotional resonance’, rather than just correctly acknowledging them.1 Alternatively, we may exercise ‘clinical detachment’, a conscious choice to numb ourselves to emotional resonance with our patients in order to maintain scientific objectivity, and to help us cope, to carry on for the benefit of the next patient in line.

Although true empathy and clinical detachment must be mutually exclusive in their purest forms, the choice between them is a false dichotomy. For the majority of clinicians, their response to emotional trauma will lie somewhere between the two, held in an uncomfortable equilibrium governed by cultural or institutional belief systems and competing doctor and patient agendas. At their extremes, true empathy and clinical detachment hold potential for unintended progression to emotional exhaustion or a generalised emotional detachment, respectively, both viewed as components of burnout, a problem affecting as many as 58% of medical residents (junior doctors).2

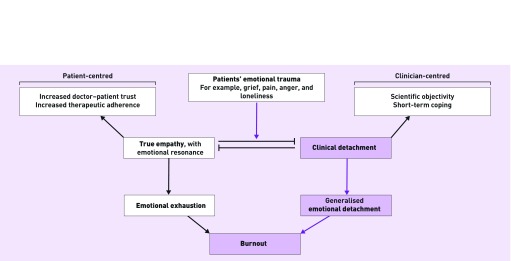

Therefore, the ideal response to emotional trauma might be an exact balance between true empathy and clinical detachment, minimising the risks associated with either extreme, while retaining some of the benefits of each approach. Unfortunately, modern medicine is heavily skewed towards clinical detachment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A response to patient emotional trauma skewed towards clinical detachment may drive long-term progression to generalised emotional detachment and burnout.

CLINICAL DETACHMENT AS THE DEFAULT

Ever since William Hunter, an 18th century surgeon–anatomist, suggested that his students should acquire ‘a necessary inhumanity’ through dissection,3 an acceptance of ‘clinical detachment’ as the appropriate disposition has become pervasive. Sir William Osler, widely viewed as the father of modern medicine, said in his 1912 essay Aequanimitas 4 that, ‘A rare and precious gift is the art of detachment’ and argued that doctors might objectively ‘see into’ a patient’s ‘inner life’ by neutralising their emotions to the point that they feel nothing in response to suffering.1 Further, Hunter’s original view of the dissection room as a training ground for developing clinical detachment has persisted into the 21st century. Hildebrandt notes that the finding that medical students at Ulm University reported decreased empathy as their dissection course progressed5 may in fact represent their having acquired the skill of clinical detachment.6

The realities of today’s clinical arena similarly drive us towards clinical detachment as the default. Rapid scientific progress has produced modern diagnostic and therapeutic options that are steeped in technical data and challenging procedures, all of which need to be managed by clear-thinking clinician-scientists. Now more than ever, the idea of clinical detachment as a prerequisite for scientific objectivity7 will ring true for health workers. This mindset may also be reinforced by the immense workloads, time pressures, and target-driven cultures of many health systems, factors that would make clinicians more likely to choose the short-term coping benefits of detachment over the patient-centred benefits of true empathy (Figure 1).

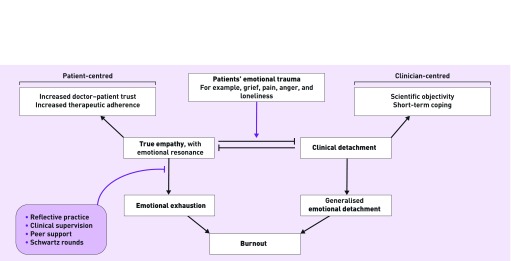

Finally, we often lack the tools to interpret troubling emotions, or we do not believe ourselves capable of doing so, meaning that we opt instead for a predominantly detached response. This real or perceived inability to process emotional resonance is the most important driver of our over-detachment because it is the most amenable to change. By promoting strategies to better interpret emotional resonance arising from patients’ traumas, we can provide a buffer, facilitating a shift back towards the ideal balance of true empathy and clinical detachment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A range of supportive interventions can reduce the likelihood of emotional resonance progressing to emotional exhaustion, allowing balance between true empathy and clinical detachment to be restored.

A SHIFT TOWARDS TRUE EMPATHY

One particularly promising way of supporting healthcare staff is the implementation of Schwartz Centre Rounds®, monthly multidisciplinary meetings focused on discussing the emotional and social aspects of health work. These 1-hour sessions involve the presentation of a case study and discussion of the emotional issues it raised, followed by time for questions, reflection, and the sharing of similar experiences, led by a trained facilitator.8 A 2012 qualitative analysis of the rounds in two UK pilot sites suggested that rounds increased respect, understanding, and empathy between staff,8 a benefit that consultant psychologist Leslie Morrison says is beginning to be shown to ‘spill over into a greater sense of compassion and empathy for patients’.

Better emotional support for healthcare workers can offer the foundations for medicine to shift towards true empathy and away from clinical detachment. Despite the short-term benefits, the long-term harms of detachment may be profound.

In her bestselling book Daring Greatly, Professor Brené Brown argues that:

‘We can’t selectively numb emotion … Numb the dark and you numb the light.’9

For healthcare workers, this means that, as the weeks of gruelling work blur into months and years, clinical detachment may lead to numbing not only the emotions of our patients, but also the emotional resonance of colleagues, friends, and those we love most.

The need to end the age of clinical detachment is urgent. If we act now to increase emotional support for healthcare staff, we can rewrite medicine’s psychological rules of engagement for years to come.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halpern J. What is clinical empathy? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):670–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira-Lima K, Loureiro SR. Burnout, anxiety, depression, and social skills in medical residents. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(3):353–362. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.936889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson R. A necessary inhumanity? Med Humanit. 2000;26(2):104–106. doi: 10.1136/mh.26.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osler W. Aequanimitas. Ravenio Books; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böckers A, Jerg-Bretzke L, Lamp C, et al. The gross anatomy course: an analysis of its importance. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(1):3–11. doi: 10.1002/ase.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hildebrandt S. Developing empathy and clinical detachment during the dissection course in gross anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(4):216. doi: 10.1002/ase.145. author reply 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulehan J, Granek IA. Commentary: ‘I hope I’ll continue to grow’: rubrics and reflective writing in medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):8–10. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823a98ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodrich J. Supporting hospital staff to provide compassionate care: do Schwartz Center Rounds work in English hospitals? J R Soc Med. 2012;105(3):117–122. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown B. Daring greatly: how the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. London: Penguin Life; 2015. [Google Scholar]