Abstract

Patient: Female, 78

Final Diagnosis: Pott’s disease

Symptoms: Back pain • nausea • vomiting • weight loss

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: MRI

Specialty: Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Pott’s disease (PD) or spinal tuberculosis is a rare condition which accounts for less than 1% of total tuberculosis (TB) cases. The incidence of PD has recently increased in Europe and the United States, mainly due to immigration; however, it is still a rare diagnosis in Scandinavian countries, and if overlooked it might lead to significant neurologic complications.

Case Report:

A 78-year-old woman, originally from Eastern Europe, presented to the emergency department with a complaint of nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and severe back pain. On admission she was febrile and had leukocytosis and increased C-reactive protein. Initial spinal x-ray was performed and revealed osteolytic changes in the vertebral body of T11 and T12. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine illustrated spondylitis of T10, T11, and T12, with multiple paravertebral and epidural abscesses, which was suggestive of PD. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the patient’s gastric fluid was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT). Based on MRI and PCR findings, standard treatment for TB was initiated. Results of the spine biopsy and culture showed colonies of MT and confirmed the diagnosis afterwards. Due to the instability of the spine and severe and continuous pain, spine-stabilizing surgery was performed. Her TB was cured after nine months of treatment.

Conclusions:

PD is an important differential diagnosis of malignancy that should be diagnosed instantly. History of exposure to TB and classic radiologic finding can help make the diagnosis.

MeSH Keywords: Hospitals, Chronic Disease; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Tuberculosis, Spinal

Background

Pott’s disease (PD) or spinal tuberculosis accounts for less than 1% of total tuberculosis (TB) cases, and usually occurs secondary to extra-spinal source of infection via the hematogenous route. Subsequently, PD may spread to an adjacent intervertebral disk or vertebra. The spinal canal can be invaded by granulomatous tissue or abscess because of direct spread from the vertebral lesion, resulting in narrowing of the spinal cord, cord compression, and later neurologic complications (e.g., paresis, paraplegia) [1,2].

The thoracolumbar vertebra is the most common site of infection in PD, although other sites in the spine can be affected, though less frequently. Back pain is the most prevalent presenting symptom. Systemic features such as fever and weight loss may present in PD; however, these symptoms are more frequent in patients with disseminated disease or concurrent extra-spinal TB [1–4].

Tentative diagnosis of PD is based on clinical suspicion (history of TB), positive tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test), acid-fast bacillus testing, positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT), or positive interferon-gamma release assays. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is capable of making tentative diagnosis at an earlier stage and remains the method of choice. Microbiologic evaluation of respiratory specimens, as well as bone tissue or abscess samples, cultured and stained for acid-fast bacilli, will confirm diagnosis [1,5,6].

Although the incidence of PD has recently increased in Europe and the United States, mainly due to immigration and an epidemic of acquired immune deficiency syndrome, it is still a rare disease in Scandinavian countries that may be overlooked. This may lead to diagnostic delay and significant neurologic complications. The authors report on a case of a 78-year-old patient with a history of two months of lower back pain who was diagnosed with PD.

Case Report

A 78-year-old woman, originally from Eastern Europe, presented to the emergency department of Svendborg Hospital, Denmark, with a complaint of severe back pain in January 2012. The pain started two months prior and had worsened a few days before the patient sought treatment. There was no history of trauma to explain the sudden worsening of back pain. The patient complained of nausea and repetitive vomiting over the previous few months. Two weeks before, the patient was referred to the department of gastroenterology, because of nausea, vomiting, weight loss, anemia, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR=61 mm/hour), to perform diagnostic gastroscopy on suspicion of malignancy. The result of gastroscopy evaluation did not show any evidence of malignant disease.

The patient had a medical history of diabetes, asthma, and hypertension, and she was treated with insulin, amlodipine, furosemide and terbutaline. On admission, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented. She was febrile with a temperature of 38.3°C. Her blood pressure (BP), pulse rate (PR), and respiratory rate (RR) were as follows: BP: 157/73 mmHg, PR: 102 beats per minute, and RR: 18 breaths per minute. She had a weight loss of 10 kilograms over the past few months. On physical examination, there was a local tenderness on the lower thoracic and lumbar area of the spine. The straight leg raise (Lasègue test) and contralateral straight leg raise caused pain in the lower back and both extremities; however, complete physical examination could not be done due to severe pain. Neurological examination, including deep tendon reflexes and sensation, was normal at that point of time. No other positive findings were found on physical examination.

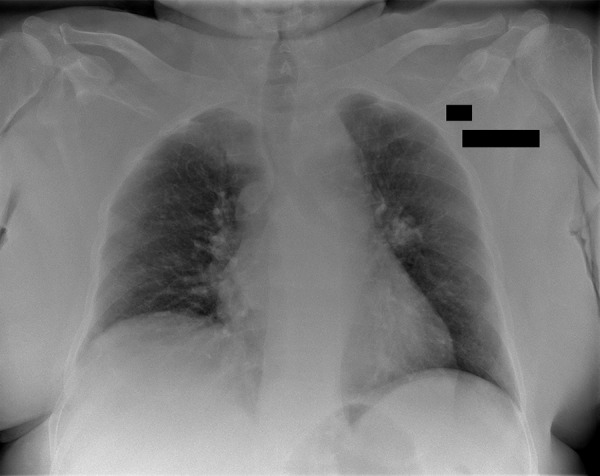

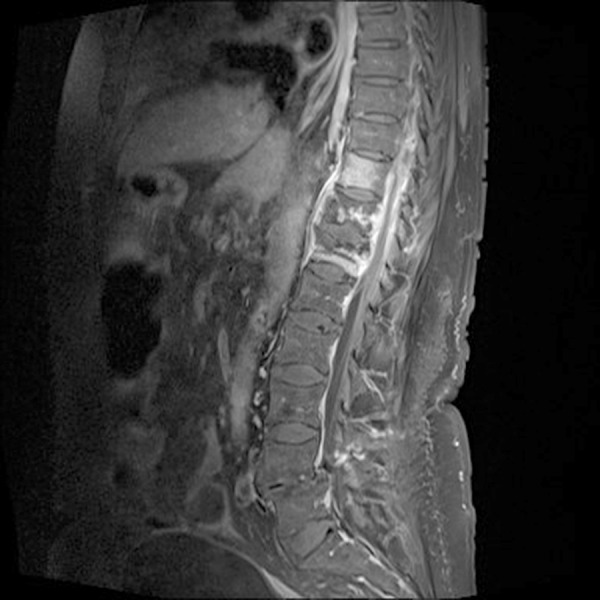

Initial laboratory evaluation revealed: hemoglobin: 7.4 mmol/L (normal range: 7.0–10.0 mmol/L), C-reactive protein (CRP): 24 mg/L (normal range: <10 mg/L), alkaline phosphatase: 181 U/L (normal range: 40–160 U/L), parathyroid hormone: 10.8 pmol/L (normal range: 1.10–6.90 pmol/L) and calcium: 1.43 mmol/L (normal range: 1.19–1.29 mmol/L). Other laboratory tests were within reference range. The result of chest x-ray did not show any abnormal findings (Figure 1). Spinal xray was performed and revealed osteolytic changes in the vertebral body of T11 and T12. Due to the suspicion of malignancy, computed tomography (CT) scan of thorax and abdomen plus CT scan of the spine were performed. The results of thorax and abdominal CT showed discrete non-malignant changes in the left lung, without any sign of malignancy or enlarged lymph nodes. The spinal CT scan demonstrated osteolytic lesions in the vertebral body of T11 and T12, which involved the epidural space. The patient was referred to the department of nuclear medicine to perform 18FDG positron emission tomography scan (18FDG PET scan) on the suspicion of malignant disease; the scan showed increased FDG uptake in the bodies of T10, T11, and T12 with osteolytic changes. There were not any signs of pathological FDG uptake in other organs. To clarify the cause of osteolytic lesions, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine was performed and revealed spondylitis of T10, T11, and T12, with multiple paravertebral and epidural abscesses (Figure 2). These rather characteristic radiological findings, concurrent with the patient’s Eastern European descent, were suggestive of PD. After this clinical suspicion of PD, a detailed patient past medical history was taken and revealed that the patient had been exposed to TB in her early childhood. The patient was subsequently transferred to the department of infectious disease for further workup. Direct microscopic evaluations of the throat secretion did not detect any signs of acid-fast bacilli. Cultures of blood and tracheal aspiration were also taken; however, they were all negative. PCR of the patient’s gastric fluid was positive for MT in one of two tests. Biopsy of the spine was performed. Based on MRI and PCR findings, standard treatment for TB with ethambutol 1200 mg daily, rifampicin 600 mg daily, pyrazinamide 2000 mg daily and isoniazid 300 mg daily was initiated. The results of spine biopsy found a large pus-filled cavity in the vertebrae and the culture was positive, showing colonies of TB bacteria and confirming the diagnosis of TB. The antimicrobial susceptibility test results revealed that the bacteria was sensitive to ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and isoniazid.

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray shows no signs of tuberculosis.

Figure 2.

Destruction of T10–T12 plus edematous intervertebral discs resulted in anterior collapse, multiple anterior and lateral paravertebral and epidural abscesses with a thin, contrast-enhanced membrane in a patient with Pott’s disease.

Due to the instability of the spine and severe and continuous pain, percutaneous posterior pedicle screw fixation under fluoroscopy guide was performed, which had a significant effect on the patient’s back pain. The clinical course of the PD was complicated with refractory hypercalcemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism, which was treated appropriately.

The patient was discharged after three weeks of hospitalization, and outpatient treatment continued for six months. Control MRI was performed after six months of treatment initiation, which revealed a small abscess concurrent with a large abscess of T10; however, there was a radiologic improvement compared to the earlier imaging studies. Due to these abscesses, anti-TB treatment was continued to nine months. The patient’s TB was cured after completion of treatment.

Discussion

PD is a rare disease that should be diagnosed immediately to prevent further neurologic complications. The principle of treatment is conservative treatment with a combination of anti-TB drugs. The standard medical treatment protocol of PD includes: isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. National and international guidelines recommend a treatment duration of six months, which may be prolonged to 9–12 months in complicated cases; however, duration of treatment is still under debate [5–10]. Shorter courses of medical treatment are associated with higher rates of adherence to treatment and lower rates of morbidity compared to long-term treatment, leading to reduced medical expenses; however, patients receiving a shorter duration of medical treatment are at higher risk of relapses during the followup period [11]. Indications for surgical intervention include: neurological deficit, spinal deformity, resistant to medical therapy, large paravertebral abscess, and indefinite diagnosis. Early surgical intervention, if surgery is indicated, is recommended to avoid further instability and neurologic complications [1,12,13]. The different surgical techniques currently considered for treatment of PD are summarized as follows: 1) anterior debridement/decompression and fusion, followed by simultaneous or sequential posterior fusion with instrumentation; 2) posterior fusion with instrumentation, followed by simultaneous or sequential anterior debridement/decompression and fusion; 3) posterior decompression and fusion with bone autografts; and 4) anterior debridement/decompression and fusion with bone auto-grafts. The first and second techniques are preferred due to significantly smaller loss of correction and a shorter period of hospitalization [14].

In 2013, a total of 355 patients with TB were reported in Denmark. Out of 355 cases, 116 (33%) and 239 (67%) had Danish origin and non-Danish origin (immigrants or descendants of immigrants), respectively. The overall incidence was 6.3 per 100,000, and bone and joint TB had an incidence of 3% (10 cases) [15]. A recent register-based analysis of bone and joint TB in Denmark from 1994 to 2011 by Johansen et al. identified 282 patients with bone and joint TB, responsible for 3.6% of all patients with TB (n=7,936). PD was found in 54.3% (153/282) of patients with bone and joint TB; 85.6% (131/153) of these patients were immigrants. The one-year mortality rate of bone and joint TB was higher in Danes in comparison with immigrants, which may be due to the fact that immigrant patients were younger and bone and joint TB were more prevalent among patients with migration background [5]. These finding were also in line with other reports in the Scandinavian and European countries [5,16].

Patients with pulmonary TB may present without any positive findings on chest x-ray; however, bacterial confirmation can help to make diagnosis in these patients [17]. In the presented case, the result of gastric aspiration was positive, showing active TB or a possible false positive result (dead myco-bacteria, laboratory contamination). The authors think that the positive PCR result in this patient was due to active TB, as PCR is a reliable test to diagnose TB with high sensitivity and specificity [18].

Outcomes for patients with PD have improved due to effective medical and surgical treatment. More than 80% of patients respond to medical treatment alone, and the mortality rate is generally lower than 10%. Surgical intervention in the presence of spine deformity or neurological deficit is required in approximately 50% of the patients [3,4,19]. Radical surgery combined with anti-TB drugs and younger age have been reported as significant favorable prognostic factors [20].

Conclusions

PD is a rare diagnosis in Scandinavian countries, including Denmark. In the presented case, PD initially masked itself as a simple back pain, later as malignancy, based on the patient’s clinical signs and symptoms. Initial laboratory evaluations were not helpful. Positive results of gastric aspirate PCR were the first clue of TB; however, the possibility of false positivity could not be ruled out. Treatment was started based on high clinical suspicion of TB, plus MRI characteristic findings. Spinal biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of TB. On the other hand, initial hypercalcemia in the patient suggested malignancy and made the diagnosis difficult. A comprehensive history with a focus on risk factors for TB (e.g., previous exposure of patient to TB, immigrant background from areas with high TB incidence) was the first lead in this case. Strong clinical suspicion should always be investigated, even if pulmonary finding are absent. PD is one of the differential diagnoses when there are radiographic signs of a destructive spinal process. In conclusion, the authors presented a rare case of PD that mimicked metastatic disease in the southern region of Denmark.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Turgut M. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott’s disease): Its clinical presentation, surgical management, and outcome. A survey study on 694 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2001;24:8–13. doi: 10.1007/pl00011973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaila R, Malhi AM, Mahmood B, Saifuddin A. The incidence of multiple level noncontiguous vertebral tuberculosis detected using whole spine MRI. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:78–81. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211250.82823.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colmenero JD, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Reguera JM, et al. Tuberculous vertebral osteomyelitis in the new millennium: Still a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:477–83. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1148-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weng CY, Chi CY, Shih PJ, et al. Spinal tuberculosis in non-HIV-infected patients: 10 year experience of a medical center in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43:464–69. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen IS, Nielsen SL, Hove M, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcome of bone and joint tuberculosis from 1994 to 2011: A retrospective register-based study in Denmark. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:554–62. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loekke A, Hilberg O, Seersholm N. National Danish Guideline for Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. 2011. Available from: http://lungemedicin.dk/fagligt/76-diagnostik-af-tuberkulose.html?path=. Accessed 15th Dec 2015.

- 7.Ramachandran S, Clifton IJ, Collyns TA, et al. The treatment of spinal tuberculosis: a retrospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:541–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for disease control and prevention Tuberculosis treatment. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/default.htm. Accessed 9th Nov 2015.

- 9.World Health Organization. Stop TB Dept . 4th edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44165/1/9789241547833_eng.pdf. Accessed 10th Jan 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thwaites G, Fisher M, Hemingway C, et al. British Infection Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. J Infect. 2009;59:167–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramachandran S, Clifton IJ, Collyns TA, et al. The treatment of spinal tuberculosis: a retrospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:541–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezai AR, Lee M, Cooper PR, et al. Modern management of spinal tuberculosis. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:87–97. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oguz E, Sehirlioglu A, Altinmakas M, et al. A new classification and guide for surgical treatment of spinal tuberculosis. Int Orthop. 2008;32:127–33. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0278-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada Y, Miyamoto H, Uno K, Sumi M. Clinical and radiological outcome of surgery for pyogenic and tuberculous spondylitis: Comparisons of surgical techniques and disease types. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(5):620–27. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.SPINE08331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statens serum institute Tuberculosis 2013. Epi-News. 2015. p. 3. Available from: http://www.ssi.dk/English/News/EPI-NEWS/2015/No%203%20-%202015.aspx. Accessed 9th Nov 2015.

- 16.Krogh K, Surén P, Mengshoel AT, Brandtzæg P. Tuberculosis among children in Oslo, Norway, from 1998 to 2009. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:866–72. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.508461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herath S, Lewis C. Pulmonary involvement in patients presenting with extra-pulmonary tuberculosis: Thinking beyond a normal chest x-ray. J Prim Health Care. 2014;6:64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng VC, Yam WC, Hung IF, et al. Clinical evaluation of the polymerase chain reaction for the rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:281–85. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakhsh A. Medical management of spinal tuberculosis: An experience from Pakistan. Spine. 2010;35:787–91. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d58c3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park DW, Sohn JW, Kim EH, et al. Outcome and management of spinal tuberculosis according to the severity of disease: A retrospective study of 137 adult patients at Korean teaching hospitals. Spine. 2007;32:130–35. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000255216.54085.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]