Abstract

The objective of this article is to examine the effectiveness of 2 theoretically different treatments delivered in juvenile drug court—family therapy represented by multidimensional family therapy (MDFT) and group-based treatment represented by adolescent group therapy (AGT)—on offending and substance use. Intent-to-treat sample included 112 youth enrolled in juvenile drug court (primarily male [88%], and Hispanic [59%] or African American [35%]), average age 16.1 years, randomly assigned to either family therapy (n = 55) or group therapy (n = 57). Participants were assessed at baseline and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months following baseline. During the drug court phase, youth in both treatments showed significant reduction in delinquency (average d = .51), externalizing symptoms (average d = 2.32), rearrests (average d = 1.22), and substance use (average d = 4.42). During the 24-month follow-up, family therapy evidenced greater maintenance of treatment gains than group-based treatment for externalizing symptoms (d = 0.39), commission of serious crimes (d = .38), and felony arrests (d = .96). There was no significant difference between the treatments with respect to substance use or misdemeanor arrests. The results suggest that family therapy enhances juvenile drug court outcomes beyond what can be achieved with a nonfamily based treatment, especially with respect to what is arguably the primary objective of juvenile drug courts: reducing criminal behavior and rearrests. More research is needed on the effectiveness of juvenile drug courts generally and on whether treatment type and family involvement influence outcomes.

Keywords: family therapy, multidimensional family therapy, juvenile drug court, adolescents, delinquency

Adolescent substance abuse and delinquency are serious public safety and health problems that together pose challenges for the juvenile justice and adolescent substance abuse treatment systems. The evidence is clear that: (a) adolescent offenders have high rates of substance use (Johnson et al., 2004;Teplin, Welty, Abram, Dulcan, & Washburn, 2011); (b) there is a strong association between substance use and repeated serious offending (D’Amico, Edelen, Miles, & Morral, 2008; Young, Dembo, & Henderson, 2007); and (c) a large proportion of juvenile justice-involved youth have drug problems severe enough to require intervention (Aarons, Brown, Hough, Garland, & Wood, 2001; Cooper, 2009). Behavioral treatment has been shown to reduce both substance use and delinquency (Chassin, Knight, Vargas-Chanes, Losoya, & Naranjo, 2009; Dennis et al., 2004), but if left untreated, drug abusing youthful offenders often engage in more serious drug involvement and criminal activity over time, perpetuating deepening personal failure and distancing from mainstream health-promoting circumstances (Ridenour et al., 2002).

The juvenile drug court (JDC) model is designed to address the link between substance abuse and criminal activity, ultimately reducing recidivism (Belenko & Dembo, 2003). Based on the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence (Wexler & Winick, 1991), drug courts are designed to produce positive outcomes both for individuals involved in the legal system, as well as for those the legal system is designed to protect (Marlowe, Festinger, Lee, Dugosh, & Benasutti, 2006). Although there appears to be considerable variation in effectiveness of among JDCs, the literature suggests that juvenile drug courts have promise (Henggeler et al., 2006; Henggeler, McCart, Cunningham, & Chapman, 2012; Hiller et al., 2010; Maring, 2006; Polakowski, Hartley, & Bates, 2008; Ruiz, Stevens, Fuhriman, Bogart, & Korchmaros, 2009; Shaffer, Listwan, Latessa, & Lowenkamp, 2008; Sloan, Smykla, & Rush, 2004). Moreover, a consensus is emerging about the essential features of effective JDCs, namely, the quality of the treatment provided, the degree to which family members are included in treatment and court proceedings, and the extent to which the JDC procedures are developmentally appropriate (Marlowe, 2010).

Among the many unanswered questions of juvenile drug courts are those concerning whether or not the type of treatment matters. Considering juvenile justice outcomes generally, some argue that all treatments are equally effective (Lipsey, 2009). Others suggest that type of treatment is important and specifically suggest that family-based treatments produce better results than individual or group interventions (Chassin et al., 2009; Doran, Luczak, Bekman, Koutsenok, & Brown, 2012). Undoubtedly, more research on juvenile drug courts is needed, particularly on the importance of the nature of treatment provided and the involvement of families (Cooper, 2009; Wilson, Mitchell, & MacKenzie, 2006).

The current study aims to build on findings suggesting that family therapy is among the most promising interventions for adolescent externalizing problems. Family therapy approaches are among the most thoroughly examined models with broad evidence to support their efficacy with youth (Becker & Curry, 2008; Henggeler &Sheidow, 2012; Rowe, 2012; Tanner-Smith, Wilson, & Lipsey, 2012), and thus seem ideal candidates for juvenile drug court. Multidimensional family therapy (MDFT), in particular, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing substance use, delinquency, and behavioral and emotional problems, and evidence suggests that the outcomes achieved in MDFT last beyond treatment discharge (Henderson, Dakof, Greenbaum, & Liddle, 2010; Liddle et al., 2001; Liddle, Dakof, Turner, Henderson, & Greenbaum, 2008; Liddle, Rowe, Dakof, Henderson, & Greenbaum, 2009).

This study addresses the question of whether or not the type of treatment matters in JDC. We conducted an intent-to-treat randomized clinical trial investigation on the effect of a family therapy, in this case MDFT, in comparison to a manualized group-based substance abuse treatment (adolescent group treatment, [AGT]) on recidivism, delinquency, externalizing symptoms and substance use. Group treatment was selected because it is the most prevalent treatment modality for adolescent externalizing disorders, generally, (Winters et al., 2011) and juvenile drug court, in particular. It should be recognized that while it has been argued that group treatment of adolescents with externalizing disorders may increase rather than decrease these problems (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999), more recent research, including numerous meta-analyses, conclude that there is little support for the notion that group therapy produces iatrogenic effects on adolescents with externalizing disorders (Lipsey, 2006; Weiss et al., 2005). Instead, results support the idea that group therapy is a safe and effective treatment for teens (Burleson, Kaminer, & Dennis, 2006).

Because of the concern that the positive effects of JDC, regardless of treatment modality, may diminish over time as judicial monitoring and surveillance decrease, we measured outcomes up to 24 months after enrollment to examine sustainability of treatment effects (Henggeler, 2007; Mitchell, Wilson, Eggers, & Mackenzie, 2012).

Given that previous research suggests that the JDC itself is a powerful intervention, we hypothesized no differences between treatment conditions during the drug court phase, expecting both groups to decrease criminal acts, delinquency, externalizing symptoms, and substance use. In the long-term follow-up period, when the intensive drug court surveillance and interventions would end, we hypothesized that youth in both treatments would show some increase in crime, delinquency, externalizing symptoms, and substance use. However, because family therapy empowers the family and other systems to support positive changes in their teens, we hypothesized that this pattern would be less pronounced in MDFT.

Method

Participants

This study was implemented in the State of Florida 11th Judicial Circuit Juvenile Court in Miami-Dade County. All youth accepted into the JDC were eligible for the study. JDC eligibility required that participants were: (a) between the ages of 13 and 18; (b) diagnosed with substance abuse or dependence based on a structured interview; (c) not actively suicidal, demonstrating psychotic symptoms, or diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder, or mental retardation; (d) not currently charged for sale of drugs, weapons, or violent offenses, or sexual battery; and (e) after consultation with their attorney, voluntarily enrolled in drug court.

Procedure

The University of Miami Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study. Youth were randomly assigned to either MDFT (n = 55) or AGT (n = 57) using an urn randomization procedure to ensure equivalence on the following established risk factors: gender, age, ethnicity, and family income. All participants randomized (N = 112) were included in the intent-to-treat analyses. Youth were assessed at intake and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months following intake, and were compensated for their participation at the following rates: intake and 6-month, $40.00; 12- and 18month, $50.00; and 24-month, $75.00. Arrest data were extracted from juvenile justice records beginning 12 months prior to intake and then continuing for 24 months after intake.

Setting and Context

Juvenile Drug Court (JDC)

Youth were adjudicated in a single drug court with one judge presiding. The only difference between the two conditions was the substance abuse treatment administered by community providers, with one providing the family treatment, and the other providing an integrated individual and peer group substance abuse treatment. The JDC incorporates the key components of drug court as defined by the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) (1997). It is organized into four phases. Progression through the phases is based on youth: (a) having consecutive clean urinalysis results and no probation violations, (b) regularly attending school/vocational training, (c) complying with substance abuse treatment, (d) improving in home behavior as reported by parent(s), and (e) attending scheduled court hearings. As youth progress through the phases, they are rewarded by having to attend fewer court hearings and having a later curfew, as well as receiving other reinforcements. Graduation includes having met an array of challenges: (a) successfully completing drug treatment; (b) having no relapse, probation violations, or rearrests for the last 4 months of drug court; (c) regularly attending and progressing well in school, GED classes, or vocational training; and (d) obtaining positive parent reports of the youth’s behavior.

The JDC team, consisting of the juvenile drug court case manager, juvenile probation officer, school liaison, and representatives from the Public Defender’s and State Attorney’s offices, reviews and discusses each case regularly. The JDC case manager completes a needs assessment at intake and serves as the liaison between the court, clinical providers, and each youth and family. Case managers provide referrals for and coordinate necessary social services, and closely supervise and monitor compliance with court orders. Therapists join the team to review the teen’s progress in treatment as needed.

Treatments

MDFT and AGT were implemented by two separate community-based treatment agencies to avoid contamination of interventions. The therapy offered to youth in both treatments lasted 4 to 6 months, with two sessions per week for MDFT and three sessions per week for AGT. Both agencies received public funding for their adolescent substance abuse treatment programs, requiring no payment from youth or families for either treatment, and were well established within the community. MDFT sessions were conducted in both the clinic and home (approximately 50% in each setting) while AGT was conducted at the clinic. Transportation assistance was provided by the court for youth in both treatments to reduce barriers to participation. All therapists had master’s degrees in counseling, social work, or related fields, and had similar experience and educational backgrounds.

Group-based treatment: AGT

The group treatment was a manual-guided intervention based on cognitive–behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing. The features and format were guided by research-supported principles and procedures and combines education, skill training, and social support (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), 1999; Godley, Risberg, Adams, & Sodetz, 2003; Kaminer, 2005; O’Leary et al., 2002). Each session was structured, beginning by goal setting/self monitoring of goal attainment, and followed by didactic/experiential activities, group processing/reflection, and closure. One therapist led each session, with between four to six male and female adolescents participating. The groups were “open” (vs. “closed”) in that new members were admitted on a rolling basis. Using a risk and protective factor framework, this treatment aimed to reduce substance use and delinquency by both targeting these behaviors directly and by focusing on accompanying risk factors, such as low self-esteem, poor academic performance, and limited social skills. Education (e.g., about communication skills) was combined with intrapersonal and relationship skill training and social support (peer sharing, practice, and feedback). Groups focused on increasing self-awareness, understanding substance abuse and delinquency triggers, developing refusal techniques, improving communication and emotion regulation skills, and increasing social competence and participation in prosocial activities. Developmentally appropriate engagement procedures and motivational enhancement techniques were employed to increase treatment participation and retention: therapist stance was active and directive but not confrontational, snacks were provided, and youth were actively involved in determining group topics and activities.

Family members were included in an assessment and treatment planning session at the beginning of treatment and were regularly informed about youth’s participation and progress, but no formal family therapy was provided. Therapists reached out to both the drug court and parents if youth failed to attend a therapy session.

Youth also received one individual therapy session each month with their group therapist. These sessions were designed to reinforce the skills learned in the group, and to address unresolved issues.

Family-based treatment: MDFT

MDFT (Liddle, 2002; Liddle, Rodriguez, Dakof, Kanzki, & Marvel, 2005) is based on the family therapy foundation established by Salvador Minuchin (Minuchin, 1974) and Jay Haley (Haley, 1976). Therapists work individually with each family. Therapists work simultaneously in four interdependent treatment domains—the adolescent, parent, family, and community. At various points throughout treatment, therapists meet alone with the adolescent, alone with the parent(s), or conjointly with the adolescent and parent(s), depending on the treatment domain and specific problem being addressed. Treatment proceeds in three stages: Stage I: build the foundation for change: alliance and motivation; Stage II: promote change in cognitions, emotions, and behavior; and Stage III: reinforce change and launch from therapy. In Stage I, treatment begins by developing a therapeutic alliance with parents and teens and enhancing their motivation to (a) participate in treatment, (b) examine themselves, and (c) begin changing their behaviors. The therapist creates an environment where both the youth and parents feel empowered, respected, and understood. Developing a strong therapeutic alliance with youth and parents and enhancing in each their motivation to examine oneself and be willing to change one’s behavior sets the foundation for relational and behavioral change.

Stage II is the longest treatment stage. The goals of the adolescent domain are to help teens communicate effectively with their parents and other adults, develop emotion regulation and coping skills, and enhance social competence and alternatives to delinquency and substance use. The therapist presents as a strong ally to the youth and help teens feel safe to reveal the truth about themselves. This is accomplished by the therapist being nonjudgmental; helping the parents control their anger and disappointment and move to a more sympathetic and problem solving stance; encouraging the youth to have positive goals (to dream and hope), and then highlighting for the youth the discrepancies between goals and continued delinquency and substance use. In the parent domain, MDFT therapists focus on increasing the parents’ behavioral and emotional involvement and attachment with their adolescent, reducing parental conflict and enhancing teamwork, and on helping parents find practical and effective ways to influence their teen (i.e., improved parenting practices). The family domain focuses on decreasing conflict, deepening emotional attachments, and improving communication and problem solving skills. The community domain fosters family competency with social systems in which the teen participates (e.g., school, juvenile justice, recreational) and helping families to better advocate for themselves with these important social systems.

Toward the end of treatment, therapists help parents and teens strengthen their accomplishments in treatment to facilitate lasting change, create concrete plans addressing how they will each respond to future problems (bumps in the road), and reinforce strengths and competencies necessary for a successful launch from treatment.

Treatment Fidelity

Attendance logs for each client were recorded to document adherence to the parameters of each treatment (the frequency and duration of treatment sessions and domains targeted). Clinical supervisors in both treatments reviewed all cases each week for fidelity to their respective models, and both treatments were also monitored by the JDC staff. Any deviations were immediately addressed both in court and directly with the treatment provider.

Adherence to MDFT techniques was measured using the Multidimensional Family Therapy Intervention Inventory (MII; Rowe, Dakof, & Liddle, 2007), which measures the fundamental interventions of MDFT. The MII has been used extensively in MDFT clinical supervision, training efforts, and randomized clinical trials, and demonstrates strong interrater reliability (Rowe et al., 2013). Independent raters view video recordings and evaluate therapy sessions on the extensiveness of 16 core MDFT interventions using a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extensively). Based on more than 650 MII ratings, it has been demonstrated that 3.0 or higher is the benchmark of adequate adherence (Rowe et al., 2013). One randomly selected family therapy session from each case was rated.

Youth in MDFT received an average of 9.40 hrs of treatment per month (SD = 4.63), and youth in AGT received an average of 10.56 hours (SD = 5.08). Youth in both treatments exceeded the prescribed minimum dose of treatment required by drug court and respective treatment protocols (8 hr per month). MDFT requires sufficient contact with adolescents alone (approximately 25–30% of total time), parents alone (20–30% of total time), families together (30–40% of total time), and work with community systems (10–20% of total time). MDFT therapists met these parameters, with MDFT participants receiving a monthly average of 3.60 hr/month of family sessions (38% of total time; (SD = 1.85), 1.82 hr/month of parent sessions (19% of total time; (SD = 1.30), 2.74 hr/month of adolescent sessions (29% of total time; (SD = 1.46), and 1.24 hr/month with community systems (13% of total time; (SD = 1.46). The majority of treatment contact for AGT was group-based, yet the treatment also included monthly individual therapy sessions, which averaged a little less than one hour per month (M = 0.70, (SD = 0.83). Family contact was limited to intake meetings and telephone calls as needed to facilitate youth participation in treatment. Comparing the treatments, youth in MDFT and AGT receive a similar amount of treatment per month (t(92) = −1.16, ns), yet youth in MDFT remained in treatment longer than youth in AGT, t(99) = 3.40, p = .001.

Ratings of therapists’ adherence to within-session MDFT interventions were analyzed based on MII ratings as described above. An independent-samples t test revealed that therapists in the current study delivered MDFT with similar fidelity as therapists collapsed across six previous MDFT trials, t(178) = 0.6, p = .5.

Measures

Measures were administered to the adolescents at baseline and at each follow-up assessment. Efforts were made to keep assessors unaware of study hypotheses and treatment assignment. The treatments were provided by two community-based clinics with offices at separate locations. Assessors’ offices were located at the University of Miami, and assessments were conducted in participants’ homes.

Demographic and background information

The intake interview was administered to obtain descriptive and demographic information. Mental health symptoms were measured with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Second Edition (DISC-2; Piacentini et al., 1993). The DISC is a semistructured interview used to identify the presence of mental health disorders according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev; American Psychiatric Association, 1987). Both youth and parent were interviewed, and the combined score was used in analyses.

Delinquent behaviors and externalizing symptoms

Youth completed the National Youth Survey (NYS), Self-Report Delinquency Scale (SRD), a well-validated instrument (Elliot, Ageton, Huizinga, Knowles, & Cantor, 1983). Two scales from the SRD were used in the current study: General Delinquency, a measure of delinquency across different levels of crime, and Index Offenses, a subscale targeting serious person and property crimes such as motor vehicle theft, aggravated assault, and forcible rape. Youth also completed the Externalizing subscales of the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991). The YSR is a widely used and validated measure of adolescent symptoms and behaviors.

Arrests

Arrest data was extracted from a justice system database maintained by the State of Florida. Arrest records were collected for the year prior to and for 2 years following intake.

Substance use

Two measures were used to assess substance use: The Personal Experience Inventory (PEI: Winters & Henly, 1989), and the Timeline Follow-Back Method (TLFB: Sobell & Sobell, 1992). Specifically, we used the Personal Involvement with Chemicals (PIC) scale of the PEI, a 29-item scale focusing on the psychological and behavioral depth of substance use involvement and related consequences in the previous 90 days. The PIC demonstrates excellent reliability and validity across diverse adolescent samples (Winters, Latimer, Stinchfield, & Egan, 2004). The TLFB measured youths’ substance consumption. The measure has been widely used in drug abuse treatment studies with adults and adolescents (Leccese & Waldron, 1994). The TLFB obtained 90-day retrospective reports of daily substance use. A frequency of substance use score was created by summing the total number of substances used over the previous 90-day period of each assessment point.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Between-treatment equivalence was tested using analyses of variance (for continuous variables) and chi-square tests (for categorical variables), and there were no significant differences (p < .05) between treatment groups at baseline on any variable, including arrest records. These results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | MDFT | AGT |

|---|---|---|

| Age [M (SD)] | 16.04 (1.12) | 16.11 (0.93) |

| Gender [n (%)] | ||

| Male | 49 (89) | 51 (89) |

| Female | 6 (11) | 6 (10) |

| Ethnicity [n (%)] | ||

| African American | 18 (33) | 22 (39) |

| Hispanic | 34 (62) | 32 (56) |

| Other | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Yearly family income [median (SD)] | $19,000 (21,090) | $20,000 (19,303) |

| Family type [n (%)] | ||

| Both parents | 18 (33) | 18 (32) |

| Single parent-mother | 27 (49) | 34 (60) |

| Other | 10 (18) | 5 (9) |

| Substance use disorders [n (%)] | ||

| Cannabis abuse | 29 (53) | 39 (68) |

| Cannabis dependence | 21 (38) | 13 (23) |

| Alcohol abuse | 12 (22) | 7 (12) |

| Alcohol dependence | 2 (4) | 3 (5) |

| Other drug abuse | 10 (18) | 9 (16) |

| Other drug dependence | 5 (9) | 3 (5) |

| Comorbidity [n (%)] | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 24 (44) | 22 (38) |

| Major depressive disorder | 4 (7) | 5 (9) |

| Conduct disorder | 29 (53) | 29 (51) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 15 (27) | 10 (18) |

| ADHD | 13 (24) | 7 (12) |

Note. MDFT multidimensional family therapy; AGT Adolescent group treatment; M mean; SD standard deviation; ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Substance Use, Delinquency, and Externalizing Symptoms

| Outcome measure | Intake M (SD) |

6 month M (SD) |

12 month M (SD) |

18 month M (SD) |

24 month M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLFB drug | |||||

| MDFT | 61.87 (43.27) | 14.89 (31.62) | 31.61 (47.45) | 32.45 (36.91) | 36.02 (45.46) |

| AGT | 66.82 (41.82) | 23.16 (41.87) | 25.76 (40.00) | 30.50 (34.80) | 38.09 (39.98) |

| PIC | |||||

| MDFT | 53.02 (14.97) | 39.76 (15.01) | 40.81 (14.20) | 44.17 (14.82) | 43.63 (16.78) |

| AGT | 51.51 (12.03) | 38.72 (12.82) | 40.58 (16.74) | 43.96 (16.72) | 47.65 (19.38) |

| General delinquencya | |||||

| MDFT T | 1.24 (1.41) | 0.90 (1.55) | 1.20 (1.69) | .63 (1.43) | .85 (1.62) |

| AGT | 1.73 (1.80) | 0.83 (1.48) | 1.46 (1.93) | .99 (1.41) | 1.07 (1.62) |

| Index offensesa | |||||

| MDFT | 0.34 (0.67) | 0.23 (0.74) | 0.33 (0.78) | 0.06 (0.33) | 0.17 (0.46) |

| AGT | 0.47 (0.99) | 0.20 (0.75) | 0.19 (0.60) | 0.20 (0.75) | 0.30 (0.82) |

| Externalizing | |||||

| MDFT | 52.44 (9.05) | 47.44 (10.79) | 45.63 (8.79) | 46.64 (9.65) | 45.78 (8.29) |

| AGT | 52.00 (11.40) | 46.37 (9.93) | 46.16 (9.04) | 45.76 (7.99) | 47.60 (9.10) |

Note. TLFB timeline follow-back (90 days); MDFT multidimensional family therapy; AGT adolescent group treatment; PIC Personal Involvement in Chemicals.

Variable log-transformed.

Response and Attrition Rates

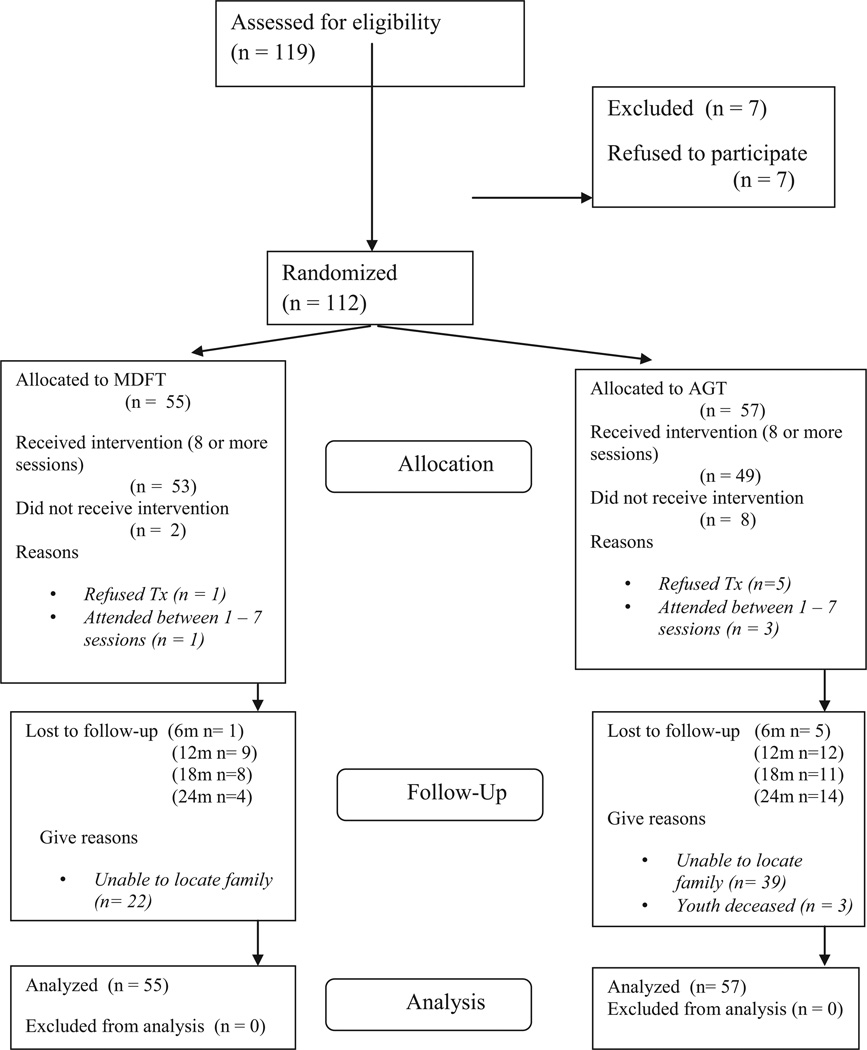

One hundred 19 youth were screened for participation. Seven declined to participate, resulting in a 94% response rate. Assessment attrition rates after randomization (total at each assessment point) were: 6 months: 5%; 12 months: 19%; 18 months: 17%; 24 months: 16%. There were no differences in assessment follow-up rates between the two treatments. See Figure 1 for details on the CONSORT flowchart.

Figure 1.

Consort E—flowchart

Data Analytic Approach

Latent growth curve (LGC) modeling using robust maximum likelihood estimation (Curran & Hussong, 2003) was used to analyze individual client change. Missing data were handled with full information maximum likelihood estimation, under the assumption that the data were missing at random (MAR, Little & Rubin, 1987). LGC modeling was conducted using Mplus (Version 6; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010) and proceeded in two stages. First, we tested a series of growth curve models representing possible forms of growth (e.g., no change, linear change, discontinuous change) to determine the overall shape of the individual change trajectories. Given the shape of the observed average outcome trajectories, we initially tested a piecewise growth model (Crawford, Pentz, Chou, Li, & Dwyer, 2003) with two distinct phases of growth representing change during treatment (between intake and 6-month follow-up) and maintenance of initial gains (between 6- and 24-month follow-up). Second, we added intervention condition and other covariates (gender, age, ethnicity, and number of previous arrests) to the models to test the impact of intervention type on initial status and change over time (i.e., the intercept and slope growth parameters). Intervention effects were demonstrated by a statistically significant slope parameter, as tested by the pseudo z test associated with treatment condition. Along with intervention condition, we tested the above mentioned covariates. To account for possible outcome selection and suppression effects due to youth periodically being placed in controlled environments (e.g., youth being detained; McCaffrey, Morral, Ridgeway, & Griffin, 2007), we also included days in placement as a covariate. Because distributions of participants’ self-reports of delinquent behavior substantially deviated from normality, we applied appropriate data transformation procedures to improve the normality of the data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). These transformations were successful in bringing skewness within acceptable levels (less than 2). Furthermore, we used the robust maximum likelihood estimator for all analyses to minimize the impact of non-normality on the results. Both effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and significance tests associated with intervention effects are reported. Effect sizes were calculated using Feingold’s (2009) method for growth curve modeling.

See Table 2 for means and standard deviations for each outcome measure at each assessment point. Outcome results are presented below by phases: Phase 1: intake through 6 months after intake, and Phase 2: 7 months through 24 months after intake. Change in the number of arrests from the year prior to entry into drug court were analyzed using zero-inflated negative binomial specifications given the nature of the outcome distribution (i.e., count data). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for Juvenile Court Records

| Outcome variable | 12 months prior to study entrya M (SD) |

Intake to 6-month follow-up M (SD) |

6- to 24-month follow-up M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrests | |||

| MDFT | 1.87 (0.94) | 0.47 (0.77) | 0.95 (1.24) |

| AGT | 2.11 (1.18) | 0.32 (0.69) | 1.19 (1.54) |

| Felonies | |||

| MDFT | 0.96 (1.22) | 0.27 (0.78) | 0.62 (1.21) |

| AGT | 1.47 (1.80) | 0.16 (0.65) | 1.07 (1.58) |

| Misdemeanors | |||

| MDFT | 1.78 (1.57) | 0.40 (0.68) | 0.98 (1.53) |

| AGT | 2.19 (1.94) | 0.25 (0.51) | 0.95(1.52) |

There were no between treatment differences in arrests, felonies, or misdemeanors in the period of 12 months prior to study entry.

Intake to 6 Months Following Intake

As hypothesized, youth in both treatments showed significant reduction in offending and substance use. The frequency of self-reported delinquent behaviors between intake and 6-month follow-up as measured by the SRD General Delinquency (Mean Slope = −0.53, standard error [SE] = 0.18, pseudo z = −2.96, p = .003, d = 0.82) and Index Offenses scales (Mean Slope = −0.19, SE = 0.07, pseudo z = −2.52, p = .012, d = 0.22) indicate statistically significant reduction in delinquency with effect sizes ranging from small for Index Offenses to medium for General Delinquency. Externalizing symptoms as measured by the YSR also significantly decreased from intake to 6 months after intake for both treatments (Mean Slope = −5.96, SE = 0.98, pseudoz = −6.08, p < .001, d = 0.99). The number of arrests from the year prior to entry into the drug court, in comparison to the drug court phase, indicated that youth in both treatments showed significant decreases in the total arrests (Mean Slope = −1.60, SE = 0.18, pseudoz = −8.97, p < .001, d = 1.37), felonies (Mean Slope = −1.71, SE = 0.32, pseudoz = −5.26, p < .001, d = 1.10), and misdemeanors (Mean Slope = −1.80, SE = 0.22, pseudoz = −8.30, p < .001, d = 1.18)1. All effect sizes were in the large range.

With respect to substance use, from intake to 6-month follow up, youth in both treatments showed a significant decrease in substance use as measured by the TLFB and the PIC (TLFB slope = −46.31, SE = 4.60, pseudo z = 10.06, p < .001, d = 3.63; PIC slope = −13.30, SE = 1.61, pseudo z = 8.29, p < .001, d = 5.21), with large effect sizes.

7 to 24 Months After Intake

We examined the extent to which the treatment gains obtained in the drug court phase were maintained over time. We hypothesized that both groups would show an increase in delinquency, externalizing symptoms, arrests, and substance use during the follow-up phase, but that MDFT youth would show less increase in this phase (i.e., greater maintenance of gains).

Unexpectedly, youth in both treatments maintained improvements in self-reported delinquent behaviors. Overall, youth did not show significant increases for any outcome (SRD General: Mean Slope = −0.10, SE = 0.07, pseudo z = −0.13, ns; SRD Index Offenses: Mean Slope = −0.02, SE = 0.03, pseudo z = −0.49, ns; YSR Ext.: Mean Slope = 1.62, SE = 1.80, pseudo z = 0.90, ns). In comparing the treatments, MDFT participants reduced their self-reported delinquency from the drug court phase through the follow-up phase significantly more than AGT on the SRD Index Offenses scale (treatment coefficient for slope = −0.11, SE = 0.05, pseudo z = −2.06, p = .040, d = 0.38), and on the externalizing scale of the YSR (treatment coefficient for slope = −.1.34, SE = −0.65, pseudo z = −2.06, p = .039, d = 0.39).The SRG General Delinquency results showed a similar but not statistically significant pattern of greater reduction in criminal behavior in MDFT than AGT during this period (treatment coefficient for slope = −0.17, SE = 0.12, pseudo z = 1.44, p = .151, d = 0.31).

As hypothesized, in comparison to the drug court phase, across treatments, youth had an increased number of arrests during the 24-month follow-up period (Mean Slope = 1.02, SE = 0.21, pseudo z = 4.91, p < .001, d = 0.88), including both misdemeanors (Mean Slope = 1.15, SE = 0.28, pseudo z = 4.06, p < .001, d = 0.76) and felonies (Mean Slope = 1.38, SE = 0.34, pseudo z = 4.05, p < .001, d = 0.88). However, although there was an in increase in follow-up period arrests in comparison to the drug court phase, it should be recognized that the arrest rate in this period was still significantly lower than baseline levels. Comparing the two treatments, results indicate that youth receiving MDFT had a significantly lower increase in felony arrests in comparison to AGT (treatment coefficient for slope = −1.36, SE = 0.69, pseudo z = 1.98, p = .048, d = 0.96). There were no differences between the two treatments with respect to total number of arrests or misdemeanors during this period (See Table 3).

As hypothesized, during the follow-up phase in comparison to the drug court phase, substance use increased for both treatments, but also remained below baseline values (TLFB, slope = 4.19, SE = 1.53, pseudo z = 2.73, p < .01, d = .47; PIC, slope = 2.18, SE = 0.68, pseudo z = 3.21, p < .001, d = 0.42). The results for the PIC indicate a nonsignificant but moderately sized effect favoring MDFT. Youth in MDFT reported having less of an increase (8%) in substance use problems between 7 and 24 months than adolescents who received AGT (19% increase; treatment coefficient for slope = −2.43, SE = 1.38, pseudo z = 1.76, p = .078, d = 0.54).

Discussion

The primary question addressed in this study is whether or not type of treatment—peer group-based versus family-based—influences short, and especially longer-term, outcomes among youth enrolled in a juvenile drug court. During the drug court phase, there were no statistically significant treatment differences on any of the outcomes measured. For both treatments, the results revealed impressive reductions in delinquent behaviors, externalizing symptoms, rearrests, and substance use. Frequency of substance use decreased 76% from intake to 6 months after intake for MDFT and 65% for AGT. During the same period, both groups showed an over 70% reduction in arrests. Thus, both treatments were effective during drug court.

Comparing the two treatments during the follow-up phase, it should be recognized that in no instance did the nonfamily-based AGT produce outcomes that were significantly better than the family treatment. Youth in both treatments showed an increase in substance use in the follow-up phase as compared to the drug court phase, but still remained significantly below baseline levels. For example, at 24 months, number of days used (in the previous 90 days) was 40% lower than at intake. There were no statistically significant differences between the two treatments on substance use.

During the follow-up phase, MDFT produced significantly better outcomes than AGT on youth self report of delinquency and externalizing symptoms. For example, on the measure of serious crime (SRD-Index Offenses), youth in MDFT continued to report a decrease in these behaviors in the follow-up phase, with a 26% decrease from the drug court phase to 24 months, and a 50% reduction from intake to 24 months after intake. In contrast, youth in AGT reported a 33% increase in serious delinquent behaviors from the drug court phase to 24-month follow-up and an overall decrease of 36% from intake to 24 months.

With respect to rearrests during the follow-up phase, there was no difference between the conditions on total arrests or misdemeanors (38% of MDFT and 42% of AGT were rearrested). On felonies, however, youth who received MDFT showed less of an increase in arrests from the drug court to the follow-up phase; 22% of MDFT youth versus 32% of AGT youth had a felony arrest during this period.

These results compare favorably with results from previous studies of JDC. For example, a quasi-experimental multisite study found that drug court participants were significantly less likely than a matched comparison sample to be arrested at 28 months after enrollment into a JDC, with 58% of JDC youth and 75% of comparison youth being arrested in this period (Shaffer, Listwan, Latessa, & Lowenkamp, 2008). Henggeler et al. (2006) reported that youth in JDC and regular juvenile court both had a 62% rearrest rate during the year after drug court enrollment.

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. The major limitation was that there was no comparison of youth in a nondrug court setting. Although the time effects are strong and significant, the results cannot address whether or not drug court outcomes are better than outcomes achieved in traditional juvenile court. The second limitation is that this study focused on one particular drug court in one community, and thus generalizability to other jurisdictions cannot be assumed given variability among drug courts. Third, the sample was primarily Hispanic (59%) and African American (36%), and male (89%), and hence the results may not be easily generalized to females or youth of other racial and ethnic groups. Fourth, the sample size was fairly small for this type of study and the results may ultimately prove unstable in a replication with a larger sample size. The final limitation that should be recognized is that although this study was designed to compare two distinct treatment formats (group vs. family), it is possible that individual attention that could be provided by the family therapists (even if divided across family members) in comparison to the group therapists (attention divided across multiple group members) could have influenced the positive MDFT results.

The study also has significant strengths. First, study methods were state-of-the-science. This study used a conservative intent-to-treat longitudinal design, had a high participant response rate, very little missing data, and employed sophisticated statistical methods. Second, as an effectiveness study, these results may be more readily applied to other real-world settings. It utilized the existing JDC inclusion and exclusion criteria, and therapists in both treatments were employed by community providers affiliated with drug court and were not research therapists. Third, the study included a 24-month follow-up, which is rare in adolescent treatment research.

The problem of youth crime and substance use is undoubtedly a public health and safety issue of the utmost significance. Judicial systems have turned to drug courts as a setting where offenders can acquire the tools needed to turn their lives and become productive members of society (Tauber & Snavely, 1999). However, many questions remain regarding the effectiveness, essential features, and long-term influence of juvenile drug courts on criminal behavior and substance abuse. The results from this study suggest that the implementation of family therapy interventions in juvenile drug courts might improve long-term outcomes, especially with respect to what is arguably the primary objective of juvenile drug courts, that is, reduction in criminal behavior and rearrest (Mitchell et al., 2012). More research is needed on the effectiveness of juvenile drug courts generally and whether family therapy interventions—with their focus on empowering families by improving parenting practices and family relationships—can enhance and sustain drug court outcomes longer than nonfamily-based interventions.

Acknowledgments

Howard A. Liddle and Cynthia L. Rowe receive financial compensation for their roles as consultants and members of the Board of Directors of Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) International, a 501(c) (3) public charity dedicated to the implementation of MDFT. Gayle A. Dakof receives financial compensation for her role as the Director of MDFT International. The work reported was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Grant R01 DA 017478. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Judges William Johnson, Lester Langer and Cindy Lederman; Sharon Abrams, Paul Indelicato, Eve Sakran, and Steve Saffron.

Footnotes

Trial Registry Name: Clinical Trials.gov, Identified NCT01668303.

The zero-inflated portions of the distributions were nonsignificant for each outcome here and below with the 7–24 month trajectories.

Contributor Information

Gayle A. Dakof, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Craig E. Henderson, Department of Psychology, Sam Houston State University

Cynthia L. Rowe, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Maya Boustani, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Paul E. Greenbaum, Department of Child and Family Studies, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida

Wei Wang, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of South Florida.

Samuel Hawes, Department of Psychology, Sam Houston State University.

Clarisa Linares, Juvenile Drug Court, State of Florida 11th Judicial Circuit Juvenile Court, Miami, Florida.

Howard A. Liddle, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

References

- Aarons GA, Brown SA, Hough RL, Garland AF, Wood PA. Prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:419–426. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ, Curry JF. Outpatient interventions for adolescent substance abuse: A quality of evidence review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:531–543. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Dembo R. Treating adolescent substance abuse problems in the juvenile drug court. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2003;26:87–110. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(02)00205-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2527(02)00205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson JA, Kaminer Y, Dennis ML. Absence of iatrogenic or contagion effects in adolescent group therapy: Findings from the Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:4–15. doi: 10.1080/10550490601003656. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10550490601003656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) Treatment of adolescents with substance use disorders Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series. Vol. 32. Washington, DC: DHHS; 1999. (Publication No. (SMA) 01–3494) [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Knight G, Vargas-Chanes D, Losoya SH, Naranjo D. Substance use treatment outcomes in a sample of male serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CS. Adolescent drug users: The justice system is missing an important opportunity. Family Court Review. 2009;47:239–252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1617.2009.01251.x. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou CP, Li C, Dwyer JH. Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. The use of latent trajectory models in psychopathology research. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:526–544. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Edelen MO, Miles JN, Morral AR. The longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among high-risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(1–2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm. Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Luczak SE, Bekman N, Koutsenok I, Brown SA. Adolescent substance use and aggression: A review. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2012;39:748–769. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0093854812437022. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Cantor RJ. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior (Report No. 26) Boulder, CO: Behavioral Research Institute; 1983. http://dx.doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR08506. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods. 2009;14:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Risberg R, Adams L, Sodetz A. Chestnut Health System’s Bloomington outpatient and intensive outpatient program for adolescent substance abuse. In: Stevens SJ, Morral AR, editors. Adolescent substance abuse treatment in the United States. Binghamtom, NY: Haworth Press; 2003. pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Haley J. Problem-solving therapy. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson CE, Dakof GA, Greenbaum PE, Liddle HA. Effectiveness of multidimensional family therapy with higher severity substance-abusing adolescents: Report from two randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:885–897. doi: 10.1037/a0020620. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW. Juvenile drug courts: Emerging outcomes and key research issues. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:242–246. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280ebb601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Randall J, Shapiro SB, Chapman JE. Juvenile drug court: Enhancing outcomes by integrating evidence-based treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:42–54. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, McCart MR, Cunningham PB, Chapman JE. Enhancing the effectiveness of juvenile drug courts by integrating evidence-based practices. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:264–275. doi: 10.1037/a0027147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ. Empirically supported family-based treatments for conduct disorder and delinquency in adolescents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:30–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00244.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller ML, Malluche D, Bryan V, DuPont ML, Martin B, Abensur R, Payne C. A multisite description of juvenile drug courts: Program models and during-program outcomes. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2010;54:213–235. doi: 10.1177/0306624X08327784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0306624X08327784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Cho YI, Fendrich M, Graf I, Kelly-Wilson L, Pickup L. Treatment need and utilization among youth entering the juvenile corrections system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26:117–128. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00164-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y. Challenges and opportunities of group therapy for adolescent substance abuse: A critical review. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1765–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leccese M, Waldron HB. Assessing adolescent substance use: A critique of current measurement instruments. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1994;11:553–563. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90007-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0740-5472(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA. Multidimensional family therapy treatment (MDFT) for adolescent cannabis users: Vol. 5. Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) manual series. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Parker K, Diamond GS, Barrett K, Tejeda M. Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent drug abuse: Results of a randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:651–688. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1081/ADA-100107661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Treating adolescent drug abuse: A randomized trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Addiction. 2008;103:1660–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Rodriguez RA, Dakof GA, Kanzki E, Marvel FA. Multidimensional family therapy: A science-based treatment for adolescent drug abuse. In: Lebow J, editor. Handbook of clinical family therapy. New York, NY: Wiley and Sons; 2005. pp. 128–163. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Multidimensional family therapy for young adolescent substance abuse: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:12–25. doi: 10.1037/a0014160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW. The effect of community-based group treatment for delinquency: A meta-analytic search for cross-study generalization. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 162–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW. The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: A meta-analytic overview. Victims & Offenders. 2009;4:124–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564880802612573. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Maring MM. North Dakota juvenile drug courts. North Dakota Law Review. 2006;82:1397–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB. Research update on juvenile drug treatment courts. Alexandria, VA: National Association of Drug Court Professionals; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Lee PA, Dugosh KL, Benasutti KM. Matching judicial supervision to clients’ risk status in drug court. Crime & Delinquency. 2006;52:52–76. doi: 10.1177/0011128705281746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011128705281746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey DF, Morral AR, Ridgeway G, Griffin BA. Interpreting treatment effects when cases are institutionalized after treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell O, Wilson DB, Eggers A, MacKenzie DL. Assessing the effectiveness of drug courts on recidivism: A meta-analytic review of traditional and non-traditional drug courts. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2012;40:60–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.11.009. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) Defining drug courts: The key components. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Justice, Drug Courts Program Office; 1997. Retrieved from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/dcpo/Define/dfdtxt.txt. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary TA, Brown SA, Colby SM, Cronce JM, D’Amico EJ, Fader JS, Monti PM. Treating adolescents together or individually? Issues in adolescent substance abuse interventions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:890–899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02619.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Shaffer D, Fisher P, Schwab-Stone M, Davies M, Gioia P. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised Version (DISC-R): III. Concurrent criterion validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:658–665. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199305000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakowski M, Hartley RE, Bates L. Treating the tough cases in juvenile drug court: Individual and organizational practices leading to success or failure. Criminal Justice Review. 2008;33:379–404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0734016808321462. [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour TA, Cottler LB, Robins LN, Campton WM, Spitznagel EL, Cunningham-Williams RM. Test of the plausibility of adolescent substance use playing a causal role in developing adulthood antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:144–155. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL. Family therapy for drug abuse: Review and updates 2003–2010. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:59–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00280.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Liddle HA. The Multidimensional Family Therapy Intervention Inventory. Miami, FL: University of Miami Center for Treatment Research on Adolescent Drug Abuse, Miami, FL; 2007. Unpublished rating manual. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C, Rigter H, Henderson C, Gantner A, Mos K, Nielsen P, Phan O. Implementation fidelity of multidimensional family therapy in an international trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz BS, Stevens SJ, Fuhriman J, Bogart JG, Korchmaros JD. A juvenile drug court model in southern Arizona: Substance abuse, delinquency, and sexual risk outcomes by gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2009;48:416–438. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10509670902979637. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer DK, Listwan SJ, Latessa EJ, Lowenkamp CT. Examining the differential impact of drug court services by court type: Findings from Ohio. Drug Court Review. 2008;6:33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan JJ, Smykla JO, Rush JP. Do juvenile drug courts reduce recidivism? Outcomes of drug court and an adolescent substance abuse program. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2004;29:95–115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02885706. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten R, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-4612-0357-5_3. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th. Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauber JS, Snavely KR. Drug courts: A research agenda. Alexandria, VA: National Drug Court Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Welty LJ, Abram KM, Dulcan MK, Washburn JJ. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: A prospective longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2012;69:1031–1043. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Caron A, Ball S, Tapp J, Johnson M, Weisz JR. Iatrogenic effects of group treatment for antisocial youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1036–1044. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X,73.6.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler DB, Winick BJ. Therapeutic jurisprudence as a new approach to mental health law policy analysis and research. University of Miami Law Review. 1991;45:979–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DB, Mitchell O, MacKenzie DL. A systematic review of drug court effects on recidivism. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2006;2:459–487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11292-006-9019-4. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Henly GA. The Personal Experience Inventory test and user’s manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Latimer WW, Stinchfield RD, Egan E. Measuring adolescent drug abuse and psychosocial factors in four ethnic groups of drug-abusing boys. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:227–236. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Lee S, Botzet A, Fahnhorst T, Realmuto GM, August GJ. A prospective examination of the association of stimulant medication history and drug use outcomes among community samples of ADHD youths. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2011;20:314–329. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2011.598834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2011.598834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DW, Dembo R, Henderson CE. A national survey of substance abuse treatment for juvenile offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]