Abstract

The increasing use of copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles (NPs) in medicine and industry demands an understanding of their potential toxicities. In this study, we compared the in vitro cytotoxicity of CuO NPs of two distinct sizes (4 and 24 nm) using the A549 human lung cell line. Despite possessing similar surface and core oxide compositions, 24 nm CuO NPs were significantly more cytotoxic than 4 nm CuO NPs. The difference in size may have affected the rate of entry of NPs into the cell, potentially influencing the amount of intracellular dissolution of Cu2+ and causing a differential impact on cytotoxicity.

Keywords: Copper oxide, nanoparticles, toxicity, A549

Introduction

In recent years, engineered NPs have been utilized in many fields, including biomedical sciences, engineering and industry1. Aside from the negative impact that these NPs may have on a range of valuable “off-target” non-human life forms2–4, the increased use of engineered NPs also raises the risk of human exposure, often via the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, due to the increased release of these particles into the environment5, 6. This raises a concern regarding the possible cytotoxicity and side effects of NPs upon human exposure7. Nanoscale particles have very high surface-to-volume ratios when compared to the bulk phase, exhibiting unique physicochemical properties that may render them cytotoxic under certain circumstances8–11.

CuO NPs contain a single phase, tenorite12. They are used for numerous applications in the electronic and optoelectronic industries such as in gas sensors, semiconductors and thin films for solar cells13–15. CuO NPs also have desirable traits for many medical applications. Recent work has shown that CuO NPs have microbiocidal activity against both fungi and bacteria16–20 and have been shown to reduce bacterial biofilm formation21, 22. CuO NPs also have a high potential to be used as a MRI-ultrasound dual imaging contrast agent23. With these increasing applications, there are many potential routes of exposure to engineered nanomaterials including CuO NPs. For example, Cu-based engineered nanomaterials are active ingredients in marine antifouling paints and agricultural biocides where they can become airborne and finally deposit in soil24, 25. Airborne nanomaterials can also be deposited into natural water bodies in addition to their direct release that can result in contaminated water systems26, 27. Furthermore, metallic Cu NPs can be released into the environment from power stations, smelters, metal foundries, asphalt, inkjet printers and rubber tires28 and can undergo oxidation under ambient conditions forming CuO NPs29. Wang et al. has shown that dissolved copper in association with CuO NPs are primary redox-active species and the CuO NPs undergo sulfidation by a dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism30.

In order to employ these metal-based engineered NPs in biomedical applications, their behavior in physiological systems needs to be addressed and fully understood. For example, particle dissolution can occur under biological conditions, specifically in the presence of natural coordinating organic acids, resulting in the release of dissolved metal ions to the surrounding solution. Dissolution can also lead to decreased particle size and in turn increased particle mobility29, 31, 32. These are important considerations for the use of NPs in biomedical research because these are factors that could be directly related to cytotoxicity.

There have been several studies conducted to evaluate the toxicity of CuO NPs. Pettibone et al. investigated the whole-body inhalation exposure of mice to copper and iron nanoparticles that showed increased inflammatory responses for copper nanoparticles three-weeks post exposure12. Karlsson et al. conducted a study on different metal oxide nanoparticles (CuO, TiO2, ZnO, CuZnFe2O4, Fe3O4, Fe2O3) and compared their toxicity to multi-walled carbon nanotubes33. The results indicated that CuO nanoparticles were the most potent regarding cytotoxicity and DNA damage and it was not entirely attributed to the dissolved ions. In another study by Fahmy et al. CuO nanoparticles were observed to overwhelm antioxidant defenses in airway epithelial cells34. Heinlaan et al. compared the toxicity of nanoscale and bulk CuO, ZnO and TiO2 using V. fischeri, D. magna and T. platyurus35. The LC50 values reported in this study for nanoscale CuO was 50–100 fold lower than for bulk CuO. A recent study by Mancuso et at. highlighted that nanoscale CuO exhibits a nearly 30-fold enhancement in cytotoxicity compared to bulk materials based when testing using human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMMSCs)36. These studies provide strong evidence of significant differences between the toxicological impacts of CuO particles depending on their particle size. Based on these findings, the nanoscale particles (particles which were approximately 20–50 nm) show considerably higher toxicities than larger micron-sized particles.

Following on these studies, we focus here on further understanding the role of particle size in CuO toxicity and to study size effects for nanoparticles below 100 nm in diameter. In particular, in this study, two sizes of CuO NPs were compared; 1) 4 nm CuO NPs, and 2) 24 nm CuO NPs. The goals of the current study were to compare the cytotoxicity of differently sized CuO NPs and investigate the specific causes of cytotoxicity induced in vitro using a human lung cell line as a representative cell type of the respiratory tract37. This study attempts to provide insight into the factors that affect the cytotoxicity of CuO NPs.

Materials and methods

Characterization of Cu-based NPs

The CuO NPs used in this study were extensively characterized for size, surface area, core and surface composition. The average particle sizes of CuO NPs were determined using transmission electron microscopy (JEOL JEM-1230 TEM). Surface areas were measured using a multipoint Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface analyzer (Quantachrome Nova 4200e) using nitrogen as the adsorbent. The bulk and surface compositions were determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), respectively. Data generated from these characterizations are summarized in Table 1. Large (24 nm) CuO NPs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) while small (4 nm) CuO NPs were synthesized in the lab according to the following protocol. A copper-containing precursor, Cu(OAc)2 (1.74 g), was added to 100 mL methanol. The solution was then refluxed for several minutes to dissolve the precursor. Afterwards, 3 mL of water was added to this solution. Upon completely dissolving Cu(OAc)2, a solution of methanol (50 mL) containing 0.7 g of NaOH was added dropwise and further refluxed for 50 hours. The resultant black precipitate was collected by evaporating the methanol on a rotary evaporator followed by multiple washings using acetone (20 mL), water (20 mL) and ethanol (20 mL) respectively. At each washing step, the nanoparticles were collected via centrifugation at 22000 rpm. Finally the collected precipitate was dried in the oven overnight at 106°C and finely ground using a mortar and pestle.

Table 1.

Summary of physicochemical characterization data of CuO nanoparticles.

| Physicochemical property |

Technique | Small CuO NPs | Large CuO NPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size (nm) | TEM* | 4 ± 1 | 24 ± 9 |

| Surface area (m2/g) | BET** | 118 ± 4 | 22 ± 0.4 |

| Bulk composition | XRD | CuO | CuO |

| Surface composition | XPS | Cu-OH, acetate | Cu-OH, carbonate |

Particle size obtained from TEM technique was expressed as mean ± SD and based on 100 particles.

Surface area obtained from BET technique was expressed as mean ± SD (n=3).

Cell culture

The human alveolar lung adenocarcinoma cell line, A549, was kindly provided by Peter S. Thorne, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, College of Public Health, University of Iowa. A549 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 media (Gibco, Life technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco), 1 mM Glutamax (Gibco) and 50 µg/mL gentamycin sulfate (IBI Scientific, Peosta, IA). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and were shown to be free of mycoplasma.

Cytotoxicity assay

A549 cells were plated 1 day prior to NP treatment in 96-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/well. In all cell-based experiments, all treatments (4 nm CuO NPs, 24 nm CuO NPs, Cu(NO3)2 and NaNO3) were dispersed in media using a sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) at 40% amplitude for 1 minute at 1 mg/mL (12.6 mM CuO) before dilution. Cu(NO3)2·3H2O and NaNO3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Cu(NO3)2 was included in the study in order to evaluate the effect on cell viability of dissolved Cu2+ in solution. These two types of CuO NPs and Cu(NO3)2 were added by normalizing against Cu2+ concentration. NaNO3 was used as a negative control for NO32− in Cu(NO3)2. Cells were exposed to different concentrations of Cu2+ ranging from 0.06 – 1.57 mM (or 5 – 125 µg/ml CuO) for 1, 4, 24 and 48 h. At the end of the indicated incubation period, the treatment in each well was replaced with 100 µL of fresh media and 20 µL of MTS tetrazolium compound (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution, Promega, Madison, WI). After 1 – 4 h, the absorbance was recorded at 490 nm using a Spectra Max plus 384 microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the absorbance value obtained for the untreated cells. All absorbance values were corrected with a blank solution (100 µL of fresh media and 20 µL of MTS tetrazolium compound).

Dissolution of Cu2+ from CuO NPs

In separate experiments, nanoparticles (4 nm and 24 nm CuO NPs) were dispersed in complete RPMI-1640 media using a sonic dismembrator at 40% amplitude for 1 minute before dilution. The NP suspensions at different concentrations of Cu2+ ranging from 0.06 – 1.57 mM (or 5 – 125 µg/ml CuO) were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 to mimic the same conditions as in cytotoxicity assays. After 4 different time points (1, 4, 24 and 48 h), the NP suspensions were centrifuged at 10016 × g for 25 mins to pellet the CuO NPs. Supernatants were collected, diluted in 5 mM HNO3 and was analyzed via inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Varian, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara., CA) to determine the dissolved Cu2+ concentration. In addition, a droplet of the supernatant was placed on a TEM grid and imaged to test the presence of any smaller nanoparticles that could not be removed from the centrifugation process29.

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by dihydroethidium (DHE) oxidation

A549 cells were plated in 60 mm2 dishes at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/dish. Twenty four hours following plating, the cells were treated with 4 mL of 4 nm CuO NPs, 24 nm CuO NPs, Cu(NO3)2 or NaNO3. The two types of CuO NPs and Cu(NO3)2 were added such that equal amounts of Cu2+ (0.12 µM Cu2+ concentration) were added for each treatment. NaNO3 was used as a negative control for NO32− in Cu(NO3)2. Following the 1, 4, 24 or 48 hours treatment, the cells were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and centrifuged at 230 × g for 5 minutes. The cells were washed with PBS containing 5 mM pyruvate and incubated for 40 mins at 37°C with 10 µM of the commercially available dye, dihydroethidium (DHE), in PBS containing pyruvate. Following incubation with the dye, the cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (FACScan: Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 20,000 cells was recorded. All groups were normalized to the untreated control group. Antimycin A (an electron transport chain blocker) which was used as a positive control increased the DHE oxidation levels by 3- to 5-fold (data not shown).

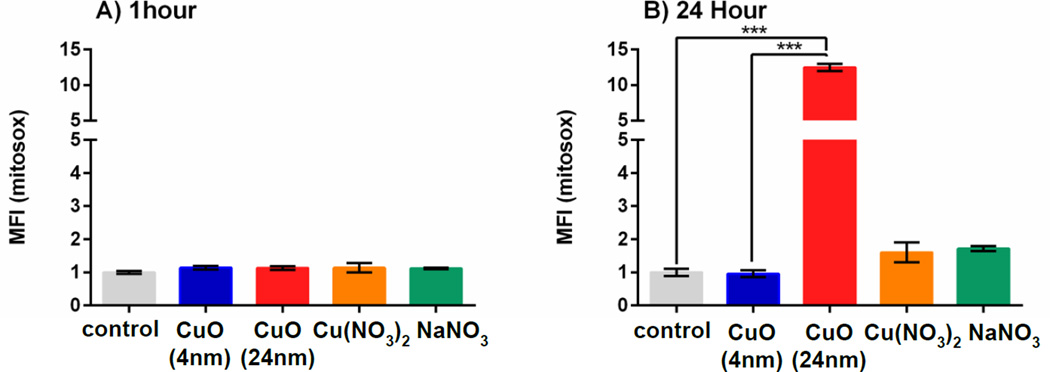

Measurement of mitochondrial ROS production via MitoSOX

A549 cells were seeded at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well in 60 mm2 dishes one day prior to treatments. Two different sizes of CuO NPs (4 and 24 nm) and Cu(NO3)2 were added such that equal amounts of Cu2+ (0.12 µM Cu2+ concentration) were added for each treatment. NaNO3 was added as a control. At two different time points (1 and 24 hours), cells were removed from dishes by trypsinization, stained with MitoSOX (final concentration 2 µM for 15 minutes) and the fluorescence was measured via flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 10,000 cells per sample was calculated. All groups were normalized to the control (untreated) group. Antimycin A was used as a positive control and showed a MFI approximately 28-fold greater than the control.

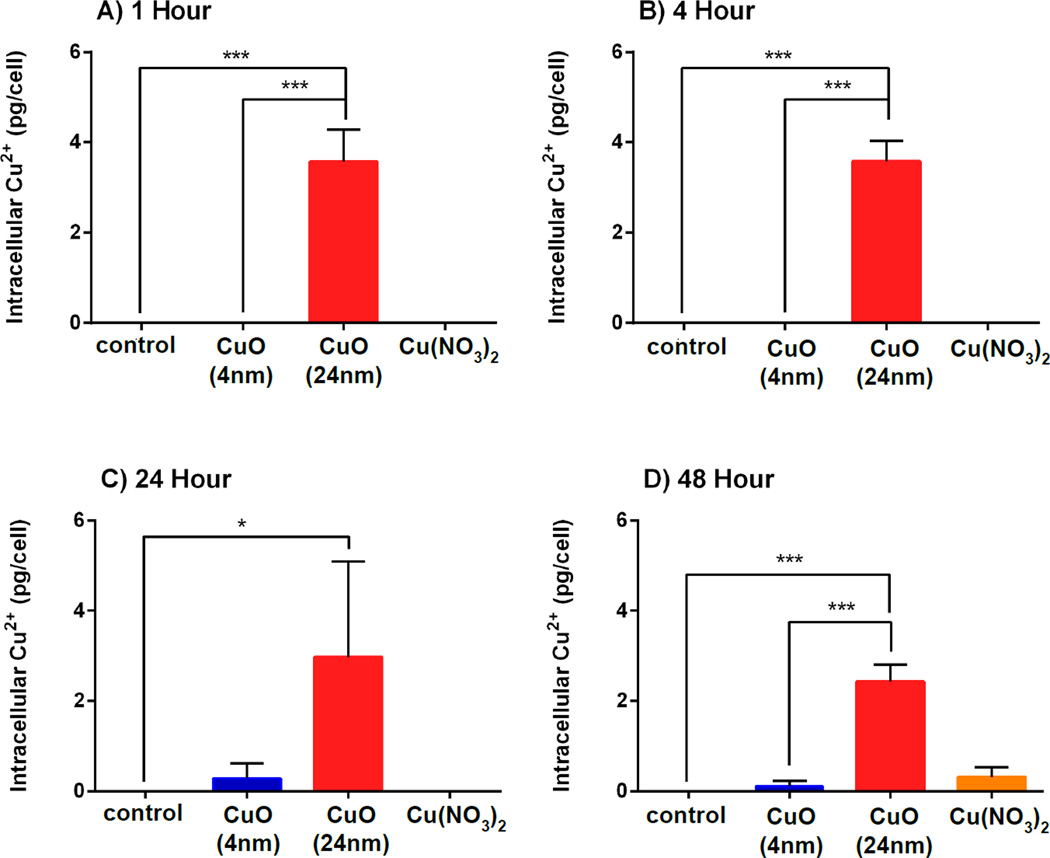

Intracellular Cu2+ uptake

A549 cells were seeded at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/well in 60 mm2 dishes one day prior to treatments. Two different sizes of CuO NPs (4 and 24 nm) and Cu(NO3)2 were added such that equal amounts of Cu2+ were added for each treatment. At 4 different time points (1, 4, 24 and 48 hours), cells were gently washed twice with warm PBS and removed from dishes by trypsinization. Cells were collected and centrifuged at 230 × g for 5 minutes, gently washed once with warm PBS and resuspended in 1 mL complete medium. These repeat washing cycles were introduced to the experiment to ensure the complete removal of extracellular CuO NPs and Cu2+. A small aliquot (20 µL) of the cell suspension was used to determine cell concentration using a hemocytometer. The rest of the cell suspension was digested with concentrated HNO3 (3 mL) using microwave digestion (MARS 6, CEM Corporation) and the Cu2+ concentration in the digestate was quantified via ICP-OES. The limit of detection for Cu2+ using ICP-OES is 5 µg/L. The Cu2+ in the digestate was used to calculate the amount of CuO in the cells (assumption: Cu2+ in the digestate is due to internalized CuO NPs or Cu2+). The intracellular Cu2+ from each sample was normalized against cell number.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. For the cytotoxicity assay, a non-linear regression with second order polynomial (quadratic), least squares fit was used. For all other experiments, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test (comparing all groups to the control group and comparing 4 nm with 24 nm CuO NPs) was performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 6.05 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, www.graphpad.com). The p-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and discussion

CuO NP characterization

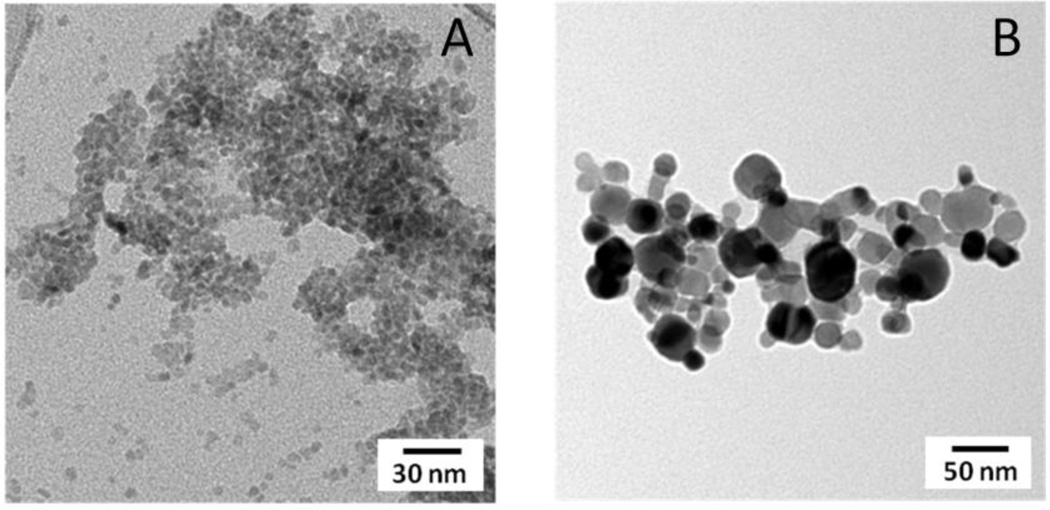

The average sizes of the CuO NPs used in these studies were 4 ± 1 nm (“small”) and 24 ± 9 nm (“large”) (Figure 1). To evaluate the effect of cell culture medium on the overall size of the CuO nanoparticles in our study, we measured the particle size of the CuO (4 nm) nanoparticles in complete media for 0 hrs, 4 hrs and 24 hrs using a Zetasizer Nano ZS at the same concentrations they were tested in the cell viability studies. The average hydrodynamic diameter for the CuO NPs tested was 5.2 ± 0.2 nm (Fig 1S.) which is consistent with the size results from the TEM analysis. RPMI medium did induce moderate levels of aggregation and the overall average particle size was stable over 24 hours. It is worth noting that changing parameters such as ionic strength, nature of buffer, particle size, particle surface composition, and percentage serum in the media can have a significant effect on the degree of aggregation and the effect of these various parameters on aggregation and cell toxicity need further investigation. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas of the small and large CuO NPs were 118 ± 4 m2/g and 22 ± 0.4 m2/g, respectively29. Bulk phase analysis with X-ray diffraction indicated that both the small and large CuO NPs consisted of a single phase; tenorite and surface analysis using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed that in both particle types the copper atoms are in the same oxidation state (Cu(II)) in the near surface region (Figure 2). These oxide nanoparticles are truncated with OH groups at the surface as indicated by the peak at 531 eV in the O1s region. In addition, the carbon 1s region of the XPS spectrum showed 4 nm CuO NPs had some surface adsorbed acetate groups resulting from the copper acetate precursor used in the synthesis process and 24 nm CuO NPs had some adsorbed carbonates on the surface. These characterization data are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images representing small (A) and large (B) CuO NPs which were used in this study. The average particle sizes of small and large CuO NPs, as determined using TEM, were 4 ± 1 nm and 24 ± 9 nm, respectively.

Figure 2.

Bulk (left) and surface (right) characterization of small (4 nm) and large (24 nm) CuO NPs using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

Comparison of cytotoxic effects of 4 nm CuO NPs versus 24 nm CuO NPs on A549 cells

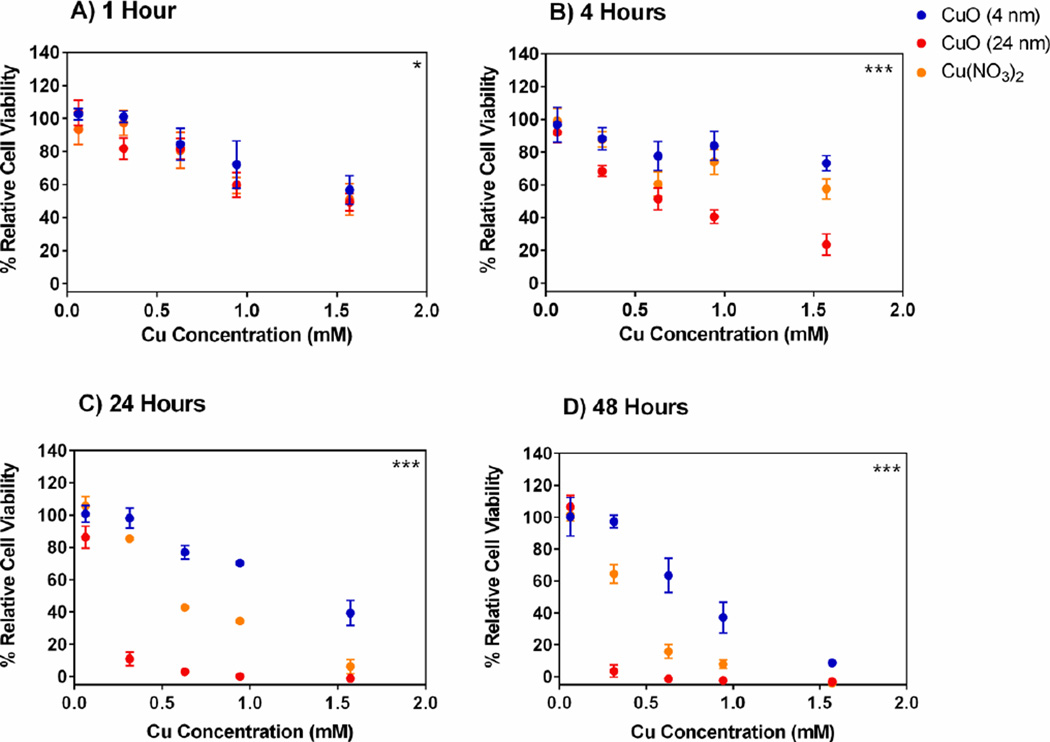

After the particles were dispersed by sonication in RPMI-1640 media, the two differently sized CuO NPs were added to A549 cells at concentrations ranging from 0.06 – 1.57 mM (of Cu2+) for 1, 4, 24 or 48 hours and the percent cell viability (relative to untreated control cells) was determined immediately after each incubation period using an MTS assay. The results (Figure 3) suggest that cytotoxicity yielded from A549 cells were dependent on both time of exposure to, and concentration of, either 4 nm CuO NPs or 24 nm CuO NPs. In addition, it was also noted that, at 1, 4, 24 and 48 h time points, there were significant differences (p-value < 0.05 for 1 h, p-value < 0.001 for 4, 24 and 48 h) in percent cell viability of A549 cells after treatment with 4 nm CuO NPs versus 24 nm CuO NPs. In short, it was apparent that 24 nm CuO NPs exhibited higher cytotoxicity compared to 4 nm CuO NPs. The higher cytotoxicity was particularly evident at 4 h, 24 h and 48 h and when concentrations of loaded Cu were 0.94 – 1.57 mM, 0.31 – 1.57 mM and 0.31 – 0.94 mM, respectively.

Figure 3. Cytotoxicity of 4 nm versus 24 nm CuO NPs.

Relative cell viability (%) of A549 cells after treatment with various concentrations of small and large CuO nanoparticles, Cu(NO3)2 solution and NaNO3 solution for A) 1 hours, B) 4 hours, C) 24 hours and D) 48 hours. The data were plotted according to concentration (mM) and expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3–4). NaNO3 was used as a control for nitrate effects and showed minimal cytotoxicity at all concentrations and all time points tested with relative cell viability > 95% (data no shown). Nonlinear regression, second order polynomial (quadratic), least squares fit were conducted to determine significant differences between 4 nm and 24 nm CuO NP treatments. *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05

Effect of dissolved Cu2+ ions on A549 cytotoxicity

Cu(NO3)2 was used as a treatment alongside solid CuO NPs in order to determine the effect of dissolved Cu2+ on cell viability. NaNO3 was used as a negative control to confirm that nitrate ions had no cytotoxic effects and that any decrease in cell viability can instead be attributed to Cu2+ in solution. There was no impact on cell viability due to treatment with NaNO3 relative to untreated cells at any time point or at any concentration (data not shown). However, the introduction of free Cu2+ from Cu(NO3)2 demonstrated both time- and concentration-dependent cytotoxicity in A549 cells. Cells treated with free Cu2+ demonstrated lower cell viability than cells treated with 4 nm CuO NPs but showed higher cell viability than cells treated with 24 nm CuO NPs (Figure 3). This was apparent at 4, 24 and 48 h incubation periods.

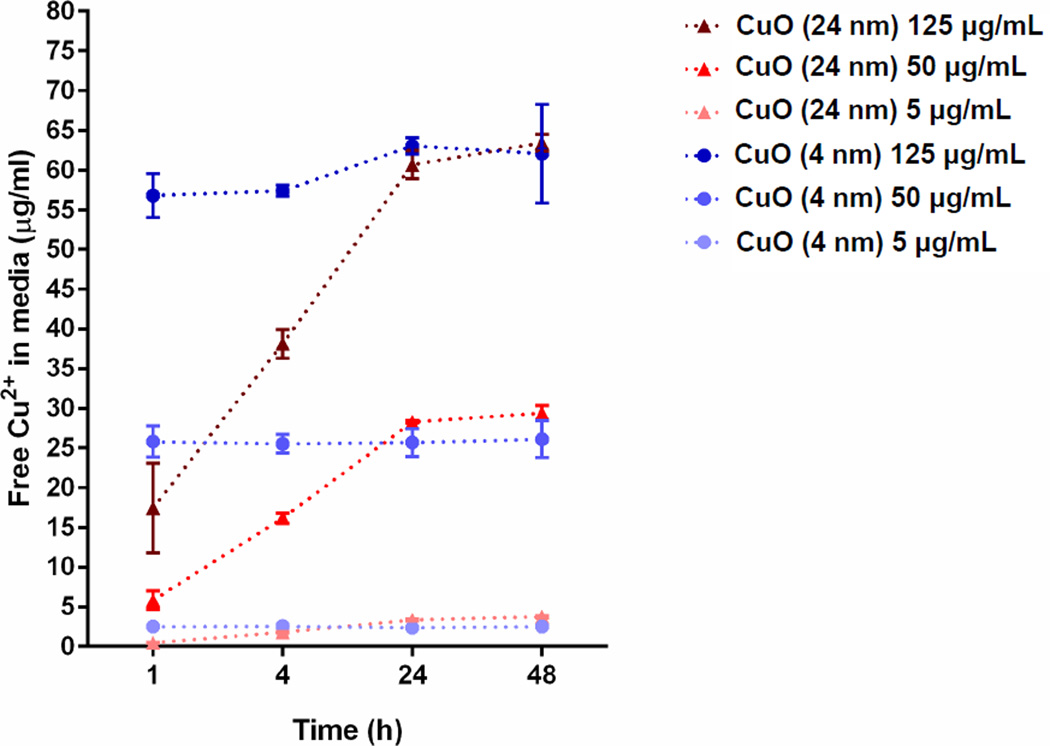

In an attempt to investigate the underlying cause of CuO NP cytotoxicity, the dissolution of Cu2+ from the two differently sized CuO NPs was measured using ICP-OES after the particles were sonicated with RPMI-1640 media and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 1, 4, 24 and 48 h (Figure 4). Three concentrations of CuO NPs (0.06, 0.63 and 1.57 mM) were chosen to represent the range of concentrations tested in the cytotoxicity assay. Because the TEM analysis of the supernatant did not show any particle presence, the concentrations obtained using ICP-OES can be attributed entirely to dissolved Cu2+. In another study, where CuO NP dissolution was tested in the presence of citric and oxalic acid, the concentrations reported by ICP-OES consisted of both dissolved and smaller CuO nanoparticles29. The concentration of free Cu2+ in the media increased as the initial concentration of 4 nm and 24 nm CuO NPs in the media increased. For all concentrations tested the complete dissolution of Cu2+ from either type of NPs was not observed after 48 h. Both types of CuO NPs released Cu2+ at similar levels at 24 and 48 h which is approximately 50% of the original concentrations. However, the rates of free Cu2+ dissolution were different. Smaller 4 nm CuO NPs achieved ~50% dissolution into the surrounding medium over a 1 h incubation period. Larger 24 nm CuO NPs took longer to reach ~50% Cu2+ dissolution (over 24 h). Thus, 4 nm CuO NPs had a faster extracellular Cu2+ dissolution rate when compared to 24 nm CuO NPs.

Figure 4. Dissolution of Cu2+ from small and large CuO NPs.

Different concentrations of particles (5, 50 and 125 µg/ml which are equal to 0.06, 0.63 and 1.57 mM, respectively) were sonicated at 40% amplitude for 1 min and then incubated in RPMI-1640 complete media for 1, 4, 24 and 48 h. The data were plotted using free Cu2+ in media against time and expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

That there is a direct relationship between the degree of cytotoxicity and the concentration of soluble extracellular Cu2+ after 24/48 hours of exposure (Figure 3) suggests that free Cu2+ in solution is likely to be one of the major causes of cytotoxicity seen with the small NPs used in these studies. In fact, free Cu2+ ions may have contributed to most of the cytotoxicity caused by the 4 nm Cu NPs. This preliminary assessment is based on the finding that the 4 nm CuO NPs released approximately 50% of their total loaded Cu as Cu2+ at 1 hour (Figure 4) and were less cytotoxic than the soluble Cu(NO3) exposed to the A549 cells at twice the concentration (for the 24 and 48 hour treatments), tentatively indicating at this stage that other factors were negligible in causing cytotoxicity. However, it appears to be a different situation for the 24 nm CuO NPs where it is likely that other or, more likely, additional factors may have contributed to the cellular cytotoxicity caused by these NPs aside from the extracellular release of Cu2+ ions. This is because 24 nm CuO NPs caused greater cytotoxicity than 4 nm CuO NPs despite the finding that 4 nm NPs had a faster Cu2+ dissolution profile than 24 nm CuO NPs. Also, the 24 nm CuO NPs were significantly more toxic than soluble Cu2+ from Cu(NO3) which was exposed to cells at more than twice the concentration of soluble Cu2+ released by the CuO NPs.

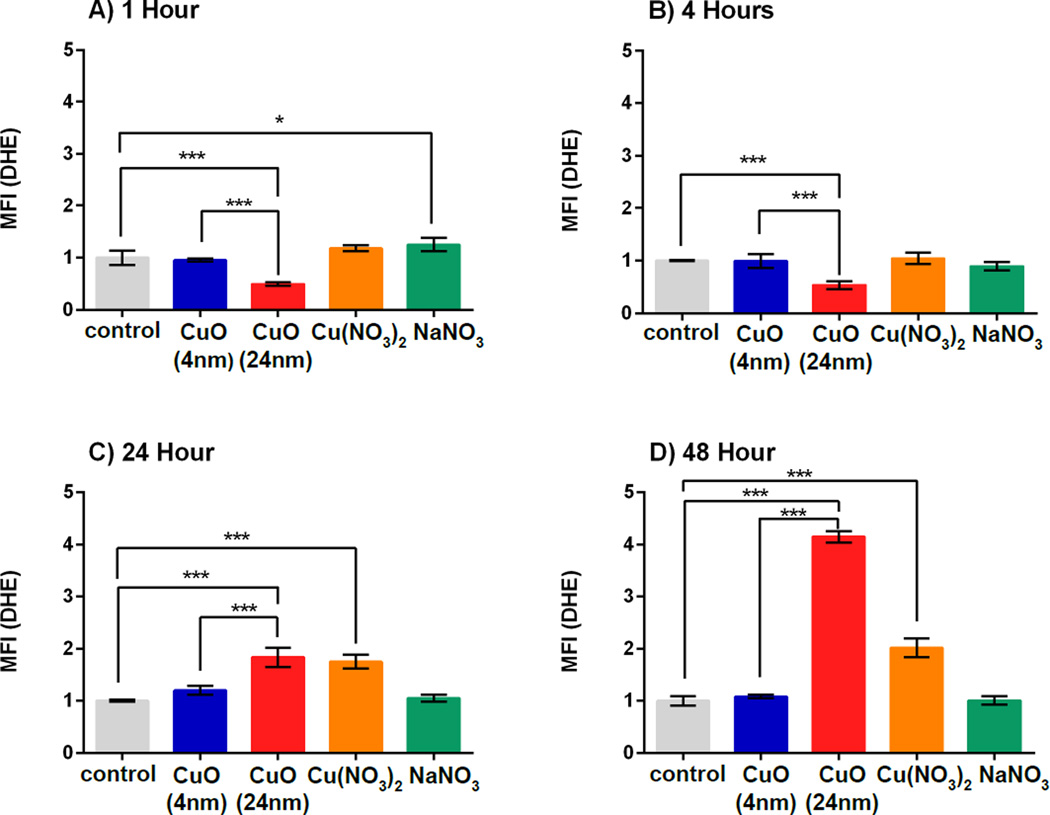

Evaluation of intracellular and mitochondrial pro-oxidants induced by CuO NPs

Intracellular prooxidant levels (intracellular O2•−) in A549 cells after treatment with 4 nm or 24 nm CuO NPs for 1, 4, 24 or 48 h were assessed through the detection of DHE oxidation, which is indicative of superoxide anions (O2•−) as well as other prooxidants. The results demonstrated that, at 1 h and 4 h (Figure 5A and 5B), there was a significant drop in prooxidant levels in cells treated with 24 nm CuO NPs which was not observed for the other treatments, including the 4 nm CuO NPs treatment. This finding for the 24 nm CuO NPs is possibly due to antioxidant defense mechanisms induced in the A549 cells in response to a metal-based NP challenge and has been shown to occur at 4 – 8 hours post-treatment in a previously published study where A549 cells were characterized for prooxidant levels after treatment with CuO NPs38, 39. When prooxidants were measured at 24 h and 48 h (Figure 5C and 5D) there were significant increases (2-fold and 4-fold, respectively) in the cells that were treated with 24 nm CuO NPs compared to controls (p < 0.001), possibly due to exhaustion of the antioxidant defense system. In comparison, cells treated with 4 nm CuO NPs over 24 h and 48 h did not exhibit a significant increase in prooxidant levels compared to untreated cells. When 4 nm and 24 nm CuO NPs were compared, cells that were treated with 24 nm CuO NPs over 24 h and 48 h exhibited significantly higher levels of prooxidants when compared with cells that were treated with 4 nm CuO NPs (p < 0.001). Cells treated with free Cu2+ produced 2-fold higher levels of prooxidants at 24 h and 48 h than untreated cells. Overall, these results are consistent with the cytotoxicity assays (Figure 3) and confirm that 24 nm CuO NPs were more toxic when compared to free Cu2+ and 4 nm CuO NPs. It is possible that differences in prooxidant levels account for differences in cytotoxicity (Figure 3) observed when comparing 24 nm CuO NPs with Cu(NO3).

Figure 5. Intracellular pro-oxidants as detected by dihydroethidium oxidation (DHE).

Cells were incubated with small and large CuO NPs, Cu(NO3)2 and NaNO3 at a dose of 0.12 µM Cu2+ concentration(10 µg/ml CuO NPs) for 1 h (A), 4 h (B), 24 h (C) and 48 h (B). Antimycin A increased the MFI by 3- to 5-fold when compared to the control group (data not shown). MFI represents mean fluorescence intensity which was normalized to the control group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post-test was performed. *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05.

Since it has been shown that CuO NPs at sizes of < 40 nm can enter mitochondria of A549 cells within 12 h of incubation39, mitochondrial superoxide production was measured in variously treated A549 cells using MitoSOX red40. Two incubation periods (1 h and 24 h) were tested. It was found that at 1 h, there were no substantive differences when comparing 24 nm CuO NPs with either the untreated control or the group treated with 4 nm CuO NPs (Figure 6A). At 24 h, cells that were treated with 24 nm CuO NPs had significantly more mitochondrial superoxide (12-fold higher than the control group) (p < 0.001 when compared to control and 4 nm CuO NPs). Cells that were treated with Cu(NO3)2 had 1.6-fold higher levels of mitochondrial ROS than the untreated cells. Mitochondrial ROS level in cells that were treated with 4 nm CuO NPs was at the same level as in untreated cells (MFI equals to 1) (Figure 6B). Treatment of cells with NaNO3 showed no significant change when compared to the untreated cells at both incubation periods. The results obtained here and with the intracellular superoxide measurements performed above demonstrate that 24 nm CuO NPs induced higher mitochondrial and intracellular ROS than 4 nm CuO NPs and this difference in ROS production was likely to be another major cause of cytotoxicity for cells treated with the 24 nm CuO NPs.

Figure 6. Mitochondrial pro-oxidants as detected by MitoSOX oxidation.

Cells were incubated with 4 nm and 24 nm CuO NPs, Cu(NO3)2 and NaNO3 at a dose of 0.12 µM Cu2+ concentration(10 µg/ml CuO NPs) for 1 h (A) and 24 h (B). Antimycin A increased the MFI by 10- to 16-fold when compared to the control group at 1 hour and 24 hours, respectively (data not shown). MFI represents mean fluorescence intensity which was normalized to the control group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3–5). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post-test (the comparison between all groups to the control and between small - large CuO NPs) was performed. *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05.

Quantification of the intracellular Cu2+ from cells that were treated with 4 nm and 24 nm CuO NPs

Both types of NPs studied here possessed similar surface and core oxide compositions (Figure 2) and the smaller 4 nm CuO NPs exhibited faster extracellular Cu2+ dissolution rates than the larger 24 nm CuO NPs (Figure 4), leading us to suspect that 4 nm CuO NPs may have been more cytotoxic than 24 nm CuO NPs. However, results from the MTS assays (Figure 3) showed that 24 nm CuO NPs were significantly more cytotoxic than 4 nm CuO NPs. This was particularly evident at 24 and 48 h for the lower Cu concentrations (Figure 3). Therefore, there are likely to be other factors, aside from Cu2+ dissolution rates, that contribute to the increased cytotoxicity of 24 nm CuO NPs. It is possible that these two types of NPs have different modes of entry or rates of uptake because of their difference in size, which consequently may affect the levels of Cu2+ accumulating within the cells.

To study the possibility of different modes of entry or rates of uptake depending on the particle size, cells were incubated with 4 nm, 24 nm CuO NPs and Cu(NO3)2 for a range of times (1, 4, 24 and 48 h), and then intracellular Cu2+ was measured using ICP-OES (Figure 7). In this experiment, cell suspensions were subjected to microwave digestion with concentrated HNO3 thus; this intracellular Cu2+ that was detected via ICP-OES could come from either free Cu2+ or CuO in particulate form. At all incubation periods, the only group demonstrating relatively high intracellular Cu2+ was the one where the cells were treated with 24 nm CuO NPs (p < 0.001). Cells that were treated with 4 nm CuO NPs or Cu(NO3)2 showed low intracellular Cu2+ concentrations compared to the cells treated with 24 nm CuO NPs. These results suggest that 24 nm Cu NPs are more rapidly and more efficiently taken up by A549 cells that 4 nm CuO NPs.

Figure 7. Intracellular Cu2+ uptake.

Cells were incubated with 4 nm and 24 nm CuO NPs, Cu(NO3)2 and NaNO3 at a dose of 0.12 µM Cu2+ concentration(10 µg/ml CuO NPs) for 1 h (A), 4 h (B), 24 h (C) and 48 h (D). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post-test (the comparison between all groups to the control and between 4nm and 24 nm CuO NPs) was performed. *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05.

There have been numerous reports on the cytotoxicity of CuO NPs both in vivo and in vitro36, 41–45. There is still, however, a large degree of conjecture as to the mechanism(s) by which these NPs mediate their cytotoxicity. These differences are likely to stem from multiple variables between studies including the cell type studied and the properties of the particles used. This is further confounded by the possibility that multiple mechanisms may be responsible for nanotoxicity of CuO NPs as opposed to one major causative factor.

Previous studies addressing CuO NPs toxicity showed that among various metal oxide NPs, CuO NPs were among the most cytotoxic33, 45. Also, CuO NPs have higher cytotoxicity when compared with CuO microparticles28, 46, 47. However, to the best of our knowledge, comparisons in toxicity of CuO NPs at the very small sizes used here have not been previously reported in the literature. Here, we measured and observed the differences in cytotoxicity of two groups of differently sized CuO NPs (4 nm and 24 nm). Surprisingly, the larger CuO NPs (24 nm) demonstrated higher cytotoxicity as well as inducing higher intracellular and mitochondrial ROS production than the smaller CuO NPs (4 nm), despite both groups of NPs having identical chemical compositions and the 4 nm CuO NPs showing faster extracellular Cu2+ dissolution rates. Interestingly, cells treated with 24 nm CuO NPs showed comparatively high intracellular Cu2+ (Figure 7). This disparity in intracellular Cu2+ levels was likely due to the larger volumes (> 200-fold) of 24 nm NPs over 4 nm NPs. To a less significant degree, it is also possible that the rates of NP uptake were different, with uptake being slower for the 4 nm CuO NPs. The rate of entry and amount of uptake of CuO NPs into the cell may have ultimately affected the level of intracellular accumulation of Cu2+ and consequently impacted on cytotoxicity in A549 cells. CuO NPs have been previously shown to rely on endocytosis to enter A549 cells39. Entry into acidic compartments (e.g. endolysosomes) results in exposure to a lower pH environment and it has been demonstrated that CuO NPs release Cu2+ more rapidly at lower pH6, 31. It may be that smaller 4 nm CuO NPs used here were not taken up by endocytosis as readily as 24 nm CuO NPs, perhaps due to their smaller diameter, which is substantially below the optimal size to trigger endocytosis, and may have relied upon an inefficient route of entry such as diffusion across the cell membrane48. Such a situation, combined with the large volume differences, could have resulted in significant differences in intracellular Cu2+ levels and impacted on cytotoxicity through mechanisms dependent on ROS generation, although additional contributions to cytotoxicity through ROS–independent pathways cannot be ruled out, such as the inactivation of vital proteins through chelation or the inactivation of metalloproteins6. Based on our findings it is likely that the two differently sized CuO NPs investigated here imparted their cytotoxic effects through mostly disparate mechanisms. The smaller (4 nm) and less toxic CuO NPs are likely to have impacted on cytotoxicity through an undefined pathway caused by the extracellular release of Cu2+ which occurred at a faster rate compared to the larger (24 nm) CuO NPs, whilst the larger CuO NPs appeared to have mediated their higher cytotoxic impact through the promotion of greater intracellular and mitochondria ROS levels as a result of increased intracellular access.

Conclusion

Exposure of A549 cells to 4 nm versus 24 nm CuO NPs was performed to assess their cytotoxicity and multiple techniques were performed in an attempt to verify the potential causes of cell death. As a general conclusion, we found that NP-induced cell death may be a result of multiple contributing and confounding factors, however, the predominant causal factor appeared to be dependent on the size of the CuO NPs. We conclude that the extracellular dissolution of Cu2+ ions from CuO NPs can be cytotoxic to A549 cells and this seemed to be the primary reason for the cytotoxicity generated by the 4 nm CuO NPs. Despite having similar physicochemical properties (aside from size), the larger 24 nm CuO NPs proved to be significantly more cytotoxic than smaller 4 nm CuO NPs and we can surmise that this was due to post-internalization events resulting in significantly enhanced levels of prooxidants. Evaluating the cytotoxicity of CuO NPs is essential in order to address the safety of using such materials in biomedical applications where there is the potential for environmental and human exposure. Further evaluation of subtle differences in CuO NP physicochemical properties and the effect of those subtle differences on intracellular behavior and how they impact on cytotoxicity of off-target organisms is warranted and would be of benefit to further understand the potential and limitations of translational and human health applications of copper oxide NPs.

Supplementary Material

Nano impact.

Cu-based NPs, especially CuO NPs need to be understood in terms of their impact on health and the environment. Of particular concern is their use as antimicrobial agents where susceptibility of target and off-target organisms to the toxic effects of these NPs overlap. We show here that the difference in size of CuO NPs can have a significant impact on cytotoxicity with smaller nanoparticles being less toxic than larger ones.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences through the University of Iowa Environmental Health Sciences Research Center, NIEHS/NIH P30 ES005605. We thank Katherine S. Waters, Histology Director of the Central Microscopy Research Facility at the University of Iowa and the Radiation and Free Radical Research Core Lab/ P30-CA086862 for technical support and the Lyle and Sharon Bighley Professorship. A. Wongrakpanich would like to thank the Office of the Higher Education Commission and Mahidol University under the National Research Universities Initiative for the support.

References

- 1.Mody VV, Siwale R, Singh A, Mody HR. Introduction to metallic nanoparticles. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010;2(4):282–289. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.72127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowack B, Bucheli TD. Occurrence, behavior and effects of nanoparticles in the environment. Environmental Pollution. 2007;150(1):5–22. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ju-Nam Y, Lead JR. Manufactured nanoparticles: An overview of their chemistry, interactions and potential environmental implications. Science of The Total Environment. 2008;400(1–3):396–414. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buzea C, Pacheco I, Robbie K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: Sources and toxicity. Biointerphases. 2007;2(4):MR17–MR71. doi: 10.1116/1.2815690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worthington KL, Adamcakova-Dodd A, Wongrakpanich A, Mudunkotuwa IA, Mapuskar KA, Joshi VB, Allan Guymon C, Spitz DR, Grassian VH, Thorne PS, Salem AK. Chitosan coating of copper nanoparticles reduces in vitro toxicity and increases inflammation in the lung. Nanotechnology. 2013;24(39):395101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/39/395101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y-N, Zhang M, Xia L, Zhang J, Xing G. The Toxic Effects and Mechanisms of CuO and ZnO Nanoparticles. Materials. 2012;5(12):2850. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grillo R, Rosa AH, Fraceto LF. Engineered nanoparticles and organic matter: A review of the state-of-the-art. Chemosphere. 2015;119(0):608–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzea C, Pacheco II, Robbie K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity. Biointerphases. 2007;2(4):MR17–MR71. doi: 10.1116/1.2815690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsaesser A, Howard CV. Toxicology of nanoparticles. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2012;64(2):129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrand AM, Rahman MF, Hussain SM, Schlager JJ, Smith DA, Syed AF. Metal-based nanoparticles and their toxicity assessment. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2(5):544–568. doi: 10.1002/wnan.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J. Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113(7):823–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pettibone JM, Adamcakova-Dodd A, Thorne PS, O'Shaughnessy PT, Weydert JA, Grassian VH. Inflammatory response of mice following inhalation exposure to iron and copper nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2008;2(4):189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klinbumrung A, Thongtem T, Thongtem S. Characterization and gas sensing properties of CuO synthesized by DC directly applying voltage. Applied Surface Science. 2014;313(0):640–646. [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Trass A, ElShamy H, El-Mehasseb I, El-Kemary M. CuO nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, optical properties and interaction with amino acids. Applied Surface Science. 2012;258(7):2997–3001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karthick Kumar S, Suresh S, Murugesan S, Raj SP. CuO thin films made of nanofibers for solar selective absorber applications. Solar Energy. 2013;94(0):299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laha D, Pramanik A, Laskar A, Jana M, Pramanik P, Karmakar P. Shape-dependent bactericidal activity of copper oxide nanoparticle mediated by DNA and membrane damage. Materials Research Bulletin. 2014;59(0):185–191. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abboud Y, Saffaj T, Chagraoui A, El Bouari A, Brouzi K, Tanane O, Ihssane B. Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of copper oxide nanoparticles (CONPs) produced using brown alga extract (Bifurcaria bifurcata) Appl Nanosci. 2014;4(5):571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thekkae Padil VV, Cernik M. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using gum karaya as a biotemplate and their antibacterial application. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:889–898. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S40599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelgrift RY, Friedman AJ. Nanotechnology as a therapeutic tool to combat microbial resistance. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2013;65(13–14):1803–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoosefi Booshehri A, Wang R, Xu R. Simple method of deposition of CuO nanoparticles on a cellulose paper and its antibacterial activity. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2015;262:999–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwala M, Choudhury B, Yadav RN. Comparative study of antibiofilm activity of copper oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles against multidrug resistant biofilm forming uropathogens. Indian J Microbiol. 2014;54(3):365–368. doi: 10.1007/s12088-014-0462-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murthy PS, Venugopalan VP, Das DA, Dhara S, Pandiyan R, Tyagi AK. Antibiofilm activity of nano sized CuO; Nanoscience, Engineering and Technology (ICONSET), 2011 International Conference on; 28–30 Nov. 2011; 2011. pp. 580–583. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perlman O, Weitz IS, Azhari H. Copper oxide nanoparticles as contrast agents for MRI and ultrasound dual-modality imaging. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2015;60(15):5767–5783. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/15/5767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conway JR, Adeleye AS, Gardea-Torresdey J, Keller AA. Aggregation, Dissolution, and Transformation of Copper Nanoparticles in Natural Waters. Environmental science & technology. 2015;49(5):2749–2756. doi: 10.1021/es504918q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tegenaw A, Tolaymat T, Al-Abed S, El Badawy A, Luxton T, Sorial G, Genaidy A. Characterization and potential environmental implications of select Cu-based fungicides and bactericides employed in U.S. markets. Environmental science & technology. 2015;49(3):1294–1302. doi: 10.1021/es504326n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garner KL, Keller AA. Emerging patterns for engineered nanomaterials in the environment: a review of fate and toxicity studies. J Nanopart Res. 2014;16(8):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowack B, David RM, Fissan H, Morris H, Shatkin JA, Stintz M, Zepp R, Brouwer D. Potential release scenarios for carbon nanotubes used in composites. Environment international. 2013;59:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Midander K, Cronholm P, Karlsson HL, Elihn K, Moller L, Leygraf C, Wallinder IO. Surface characteristics, copper release, and toxicity of nano- and micrometer-sized copper and copper(II) oxide particles: a cross-disciplinary study. Small. 2009;5(3):389–399. doi: 10.1002/smll.200801220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mudunkotuwa IA, Pettibone JM, Grassian VH. Environmental implications of nanoparticle aging in the processing and fate of copper-based nanomaterials. Environmental science & technology. 2012;46(13):7001–7010. doi: 10.1021/es203851d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, von dem Bussche A, Kabadi PK, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Biological and environmental transformations of copper-based nanomaterials. ACS nano. 2013;7(10):8715–8727. doi: 10.1021/nn403080y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elzey S, Grassian VH. Nanoparticle dissolution from the particle perspective: insights from particle sizing measurements. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2010;26(15):12505–12508. doi: 10.1021/la1019229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin Y, Zhao X. Cytotoxicity of Photoactive Nanoparticles. In: Webster TJ, editor. Safety of Nanoparticles. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson HL, Cronholm P, Gustafsson J, Moller L. Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: a comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21(9):1726–1732. doi: 10.1021/tx800064j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fahmy B, Cormier SA. Copper oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in airway epithelial cells. Toxicology in Vitro. 2009;23(7):1365–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinlaan M, Ivask A, Blinova I, Dubourguier HC, Kahru A. Toxicity of nanosized and bulk ZnO, CuO and TiO2 to bacteria Vibrio fischeri and crustaceans Daphnia magna and Thamnocephalus platyurus. Chemosphere. 2008;71(7):1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancuso L, Cao G. Acute toxicity test of CuO nanoparticles using human mesenchymal stem cells. Toxicology mechanisms and methods. 2014;24(7):449–454. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2014.928920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahu SC, Casciano DA. Nanotoxicity: From In Vivo and In Vitro Models to Health Risks. Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi X, Castranova V, Vallyathan V, Perry WG. Molecular Mechanisms of Metal Toxicity and Carcinogenesis. US: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, Li N, Zhao J, White JC, Qu P, Xing B. CuO nanoparticle interaction with human epithelial cells: cellular uptake, location, export, and genotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25(7):1512–1521. doi: 10.1021/tx3002093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Yoshihiro K, Haskó G, Pacher P. Simple quantitative detection of mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;358(1):203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melegari SP, Perreault F, Costa RH, Popovic R, Matias WG. Evaluation of toxicity and oxidative stress induced by copper oxide nanoparticles in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Aquat Toxicol. 2013;143:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossetto AL, Melegari SP, Ouriques LC, Matias WG. Comparative evaluation of acute and chronic toxicities of CuO nanoparticles and bulk using Daphnia magna and Vibrio fischeri. The Science of the total environment. 2014;490:807–814. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isani G, Falcioni ML, Barucca G, Sekar D, Andreani G, Carpenè E, Falcioni G. Comparative toxicity of CuO nanoparticles and CuSO4 in rainbow trout. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2013;97:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai L, Banta GT, Selck H, Forbes VE. Influence of copper oxide nanoparticle form and shape on toxicity and bioaccumulation in the deposit feeder, Capitella teleta. Marine environmental research. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ivask A, Titma T, Visnapuu M, Vija H, Kakinen A, Sihtmae M, Pokhrel S, Madler L, Heinlaan M, Kisand V, Shimmo R, Kahru A. Toxicity of 11 Metal Oxide Nanoparticles to Three Mammalian Cell Types In Vitro. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2015;15(18):1914–1929. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150506150109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semisch A, Ohle J, Witt B, Hartwig A. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of nano - and microparticulate copper oxide: role of solubility and intracellular bioavailability. Particle and fibre toxicology. 2014;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlsson HL, Gustafsson J, Cronholm P, Moller L. Size-dependent toxicity of metal oxide particles--a comparison between nano- and micrometer size. Toxicol Lett. 2009;188(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao H, Shi W, Freund LB. Mechanics of receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(27):9469–9474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503879102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.