Abstract

Purpose

Diabetic retinopathy is manifested by excessive angiogenesis and high level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the eye.

Methods

Human (MIO-M1) and rat (rMC-1) Müller cells were treated with 0, 5.5, or 30mM glucose for 24 hours. Viable cell counts were obtained by Trypan Blue Dye Exclusion Method. ELISA was used to determine VEGF levels in cell medium.

Results

Compared to 24 hour treatment by 5.5mM glucose, MIO-M1 and rMC-1 in 30mM glucose increased in viable cell number by 38% and 24% respectively. In contrast, viable cells in 0mM glucose decreased by 28% and 50% respectively. Compared to 5.5mM, MIO-M1 and rMC-1 in 30mM glucose had increased levels of VEGF in cell medium (pg/ml by 24% and 20%) and also VEGF concentration in cells held in 0mM increased by 47% and 10% respectively. In both MIO-M1 and rMC-1, the amount of VEGF secreted per cell increased by about 100% when glucose was changed from 5.5 to 0mM but decreased slightly (17% in MIO-M1 and 11% in rMC-1) when glucose was increased from 5.5 to 30mM.

Conclusions

Our results show that MIO-M1 and rMC-1 are highly responsive to changes in glucose concentrations. 30mM compared to 5.5mM significantly increased cell viability but induced a significant change in VEGF secretion per cell in rMC-1 only. At 0, 5.5, and 30mM glucose, MIO-M1 secreted about 5-7-fold higher level of VEGF (pg/cell) than rMC-1. The mechanism of glucose-induced changes in rMC-1 and MIO-M1 cell viability and VEGF secretion remains to be elucidated.

Keywords: Diabetic Retinopathy, Angiogenesis, VEGF, Müller Cells, Retina

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a complication of the eye due to prolonged diabetes. In the United States, the prevalence of DR in a diabetic age group of 18 or older is 1 in 300 [1]. Glycemic control, diabetic duration, blood pressure control, blood lipids, among others are major determinants in the development and severity of DR [2-5]. Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) is characterized by loss of capillaries, pericyte dropout, and formation of microaneurysms [6-9]. NPDR progression to proliferative stage (PDR) is characterized by neovascularization and excessive angiogenesis [10-12] which causes swelling of capillaries and leakage of fluids on aqueous and vitreous humors, as well as retinal detachment [13], eventually leading to partial or complete vision loss.

There are various growth factors associated with diabetic retinopathy [14]. One of the widely investigated known growth factors is Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). VEGF is a group of glycoproteins existing in many isoforms [15]. VEGF/VEGF-A (a 45KDa glycoprotein) is known to promote neovascularization and angiogenesis [16, 17]. VEGF is secreted by retinal pigment epithelial cells, endothelial cells, pericytes, ganglion cells, choroidal fibroblast cells, Müller cells and others in the retina [18-24]. The VEGF levels in DR may partly be elevated due to oxidative stress, glycation products [25], and hypoxia.

Müller cells are one of the three types of glial cells in the retina. They span radially along the thickness of the retina and play a key role in maintaining retinal homeostasis [26]. Previous studies suggest that VEGF derived from Müller cells promote retinal vascularization in DR [27, 28]. The objective of this study is to investigate how high glucose and glucose deprivation affect human and rat Müller cell viability and VEGF secretion.

Material and Methods

Cell Culture

Spontaneously immortalized human Müller cells (MIO-M1) were a gift from Dr. Astrid Limb (University College, London, UK). Cells were seeded into T25 flasks and maintained at 37°C + 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's Minimum Essential Medium (DMEM) containing 4.5g/L glucose and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (growth medium) until confluent. SV40 transformed rat Müller cells (rMC-1) were obtained from Dr. Vijay Sarthy (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA). The cells were seeded into T75 flasks and maintained at 37°C + 5% CO2 in DMEM containing 1 g/L glucose and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (growth medium) until confluent.

Glucose Treatment

In a 24 well plate, 20,000 MIO-M1/well or 23,000 rMC-1/well (T0) were treated without glucose (0mM), normal glucose (5.5mM) or high glucose (30mM) in triplicates for 24 hours. Different glucose concentrations were prepared by adding D-Glucose to serum-free and glucose-free DMEM. After 24 hour treatment, the cell medium was collected from each well and was stored at −20°C (for performing ELISA later). All experiments were repeated three or more times with similar results.

Trypan Blue Dye Exclusion Method

Cells were collected at T0 and again after 24 hours as described above. The cells were diluted 1:1 using Trypan Blue (Corning, Catalog number: 25-900 Cl) and viable cells were counted using a Neubauer Hemocytometer.

hVEGF Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Essay (ELISA)

ELISA was performed on cell medium for human VEGF according to manufacturer instructions (CAT# DVE00; R&D Systems) and analyzed using a DYNEX MRXII plate reader equipped with Revelation software or BioRad microplate reader with Manager Software. Data was quantified in comparison to VEGF standards.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism Software (Version 6.07) was used to perform statistical analysis. One-way ANOVA was used to determine differences between treatment groups and Tukey's Multiple Comparison Post-hoc test was used to compare difference between two groups. P≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All results were collected in triplicates (except for 5.5mM MIO-M1 n=2) and all data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Concentration dependent change in Cell Viability

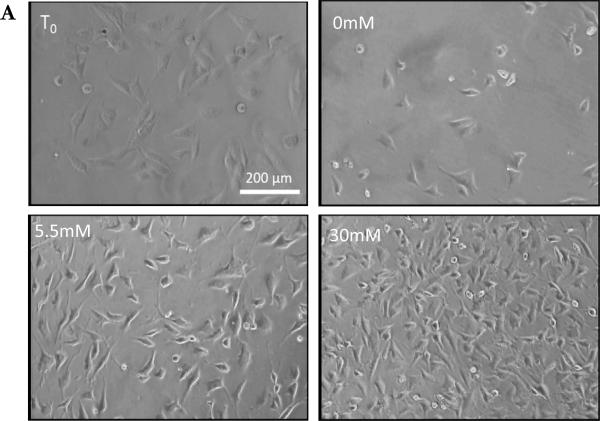

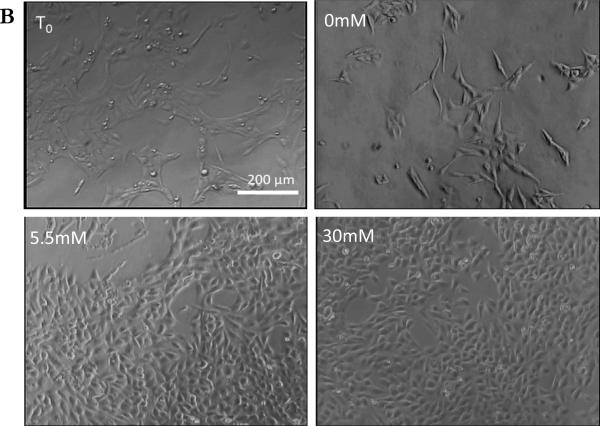

Treatment with different glucose concentrations resulted in a significant change in cell confluence and cell number (Figure 1 and 2). MIO-M1 were plated at 20,000 cells/well and after 24 hour treatment, the number of cells in 5.5mM and 30mM increased by 11% and 62% respectively (Figure 2A). In contrast, the number of cells in 0mM decreased by 20%. (Figure 2A). Results from one-way ANOVA indicate a significant effect of glucose concentration on cell number (P=0.009). rMC-1 were plated at 23,000 cells/well and after treatment for 24 hours, the number of cells in 5.5mM and 30mM increased significantly by 77% and 119% respectively (Figure 2B). However, the number of cells in 0mM decreased by 11% (Figure 2B). Results from one-way ANOVA show the glucose treatment effect on cell number was significant (P=0.001). Both MIO-M1 and rMC-1 responded to glucose treatment in a similar manner: namely a notable decrease in cell viability when treated with 0mM glucose but a significant increase in cell number when treated with 5.5mM and 30mM over a 24 hour period.

Figure 1.

Effect of Glucose on Müller Cells confluence: A.) Light microscope images of MIO-M1 grown in T0 and 0, 5.5 and 30mM glucose for 24 hour. Images from cells in 5.5mM and 30mM show increase in confluence than T0, and images from cells in 0mM show a large decrease in confluence. All images were taken at 100X magnification.

B.) Light microscope images of rMC-1 grown in T0 and 0, 5.5 and 30mM glucose for 24 hour. Images from cells in 5.5mM and 30mM were highly confluent than T0, and comparatively cells in 0mM show large decrease in confluence. All images were taken at 100X magnification.

Figure 2.

Effect of Glucose on Müller Cells Viability: A.) Concentration-dependent change in cell viability of MIO-M1. MIO-M1 were plated at 20,000 per ml in a 24 well plate. After 24 hours of glucose treatment, there were 15,926 cells in 0mM (no glucose), 22,222 cells in 5.5mM (normal glucose) and 32,592 cells in 30mM (high glucose). Results from One-way ANOVA was significant (F (2, 5) =34.71, P=0.001). A Tukey's multiple comparison test was performed to compare pairwise mean differences (**P ≤ 0.05).

B.) Concentration-dependent change in cell viability of rMC-1. rMC-1 were plated at 23,000 per ml in a 24 well plate. After 24 hours of glucose treatment, there were 20,370 cells in 0mM (no glucose), 40,741 cells in 5.5mM (normal glucose), and 50,370 cells in 30mM (high glucose). Results from One-way ANOVA was significant (F (2, 6) =11.24, P=0.009). A Tukey's multiple comparison test was performed to compare pairwise mean differences (**P ≤ 0.05).

Effect of Glucose on VEGF levels in cell media (pgVEGF/ml)

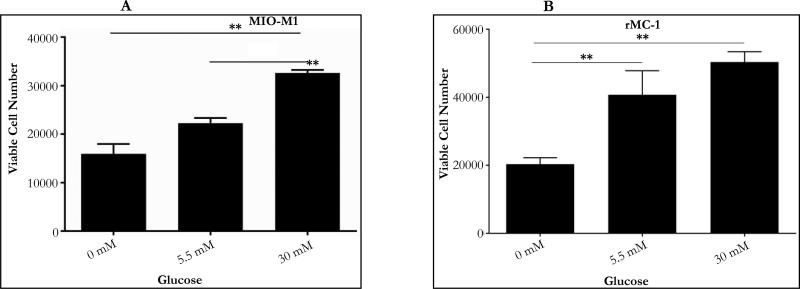

Glucose treatment (for a 24 hour period) resulted in a minimal change in VEGF concentration (pgVEGF/ml) in the cell medium. MIO-M1 cells treated with 0, 5.5 and 30mM glucose secreted 239, 163 and 202pgVEGF/ml in cell media (Figure 3A). Similarly, rMC-1 treated with 0, 5.5 and 30mM glucose had 49, 44 and 53 pgVEGF/ml in cell media (Figure 3B). Results from One-way ANOVA show that the glucose treatment did not show a significant glucose effect on VEGF concentration in the condition media in both MIO-M1 (P=0.54) and rMC-1(P=0.38). However, it is noted that the VEGF concentration in MIO-M1cell media was about 3-5 times higher than VEGF concentration in the media of rMC-1 suggesting that MIO-M1 cells synthesize and secrete a higher level of VEGF than rMC-1 in culture.

Figure 3.

VEGF secretion in cell medium for a 24 hour glucose treatment: After 24 hour glucose treatment the VEGF secreted in conditioned medium was measured for hVEGF using ELISA plate.

A. Concentration-dependent change in VEGF level in cell medium in MIO-M1: Cells in 0mM secreted 239pgVEGF/ml of VEGF, 162.5pgVEGF/ml in 5.5mM and 201.6pgVEGF/ml in 30mM. Results from One-way ANOVA was not significant (F (2, 5) =0.678, P=0.54).

B. Concentration-dependent change in VEGF level in cell medium in rMC-1: Cells in 0mM secreted 48.5pgVEGF/ml of VEGF, 44.16pgVEGF/ml in 5.5mM and 52.83pgVEGF/ml in 30mM. Results from One-way ANOVA was not significant (F (2, 6) =1.115, P=0.38).

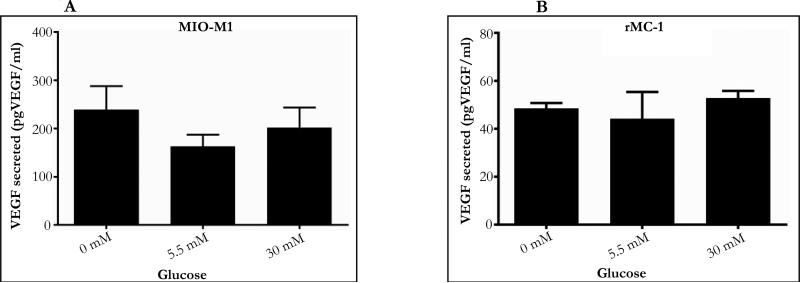

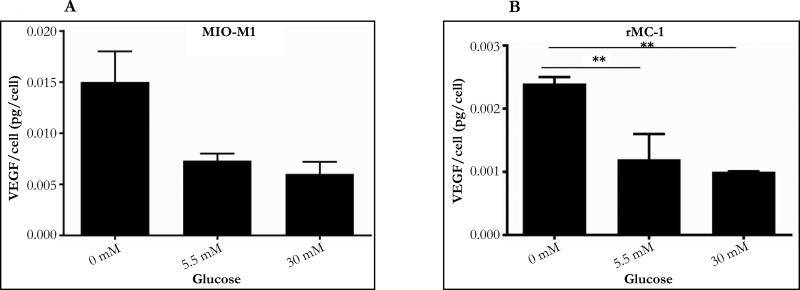

Concentration dependent change in VEGF secretion (pgVEGF/cell)

The amount of VEGF secreted per cell was calculated by dividing VEGF concentration in cell medium by the number of cells in the 1-ml culture well. In both MIO-M1 and rMC-1, a concentration dependent change in VEGF secretion (pgVEGF/cell) was observed in which an increase in glucose concentration resulted in a decrease in VEGF secretion. In both MIO-M1 and rMC-1, the amount of VEGF secreted per cell increased by 2-fold (100% increase) when glucose was changed from 5.5 to 0mM, but decreased by about 17% in MIO-M1 and 11% in rMC-1 respectively, when glucose was increased from 5.5 to 30mM. In MIO-M1 cells, increase in glucose concentration from 0mM to 30mM resulted in a 2-fold reduction in VEGF secretion (from 0.0150 to 0.0065 pgVEGF/cell) and a similar 2-fold reduction of VEGF secretion was also observed when rMC-1 cells were subjected to a change in glucose concentration from 0mM to 30mM (from 0.0024 to 0.0010 pgVEGF/cell. Results from one-way ANOVA show a significant glucose effect on VEGF secretion in rMC-1 cells only (P=0.01). However, the level of VEGF secretion (pgVEGF/cell) by MI0-M1 cells at 0, 5.5 and 30mM glucose was about 5-7 fold higher than VEGF secretion by rMC-1 cells.

Discussion

The objective of the present study is to investigate the effect of glucose on human and rat Müller cell viability and VEGF secretion. Compared to physiological glucose (5.5mM), high glucose (30mM) increase cell viability in both Müller cell types (Figures 1 and 2). This is consistent with results of others using primary rat Müller cells [29]. In another study, the density of Müller cells in retina increased significantly in 4 week old diabetic rats [30]. It is possible that under high glucose conditions enhanced entry of calcium to Müller cell may activate a process that leads to increase in cell proliferation [31]. As Müller cells contribute significantly to VEGF in the retina, the increase in Müller cell number in response to high glucose suggests that Müller cell may play an important role in elevated VEGF level in the diabetic retina.

In the present study, we also observed that 0mM glucose significantly decreased cell viability. This is consistent with a report which shows that primary rat Müller Cells decreased cell viability when they are glucose deprived (0mM) [32]. It is possible that Müller cells are highly dependent on glucose availability thus the lack of glucose may severely impact cell viability. Further experiment will be needed to clarify the effect of glucose deprivation. The possible explanation for opposite observations is that decrease of glucose from 5.5 to 0mM deprived the minimal sustainable level of glucose resulting in a decrease in cell viability. However, an increase from 5.5mM to 30mM resulted in an excess of glucose to a level to activate other mechanisms such as the entry of calcium leading to cell proliferation.

When glucose concentration was increased from 0 to 30mM, there was a significant decrease in VEGF protein secretion (pgVEGF/cell, Figure 4). However, other studies show that high glucose increased VEGF expression at mRNA and protein levels in primary rat Müller cells [29, 33, 34] in a concentration and time dependent manner [35, 36]. It is not clear if high glucose induces increase in expression of VEGF protein which accumulates but not released by Müller cells. Additional experiments will be needed to clarify this point.

Figure 4.

VEGF secretion per cell for a 24 hour glucose treatment: VEGF/cell was calculated by dividing VEGF levels measured in cell medium with respective cell number.

A. Concentration dependent change in VEGF secretion per cell in MIO-M1. After 24 hours each cell secreted VEGF 0.0150pgVEGF/cell in 0mM, 0.0073pg/cell in 5.5mM and 0.0061pgVEGF/cell in 30mM. Results from One-way ANOVA was not significant (F (2, 5) =5.292, P=0.058).

B. Concentration dependent change in VEGF secretion per cell in rMC-1. VEGF/cell was calculated by dividing VEGF levels measured in cell medium with respective cell number. After 24 hours each cell secreted VEGF about 0.0024pgVEGF/cell in 0mM, 0.0012pgVEGF/cell in 5.5mM and 0.0010pgVEGF/cell in 30mM. Results from One-way ANOVA was signifi-cant (F (2, 6) =10.11, P=0.01). Tukey's multiple comparison test was performed to compare pairwise mean differences (**P ≤ 0.05).

The observation that MIO-M1 in culture secreted 3-5 folds more VEGF than rMC-1 (Figures 3 and 4) may be merely be due to species differences (human vs rat) and protein expressions in different cell lines (such as method of cell transformation).

In the present study, we did not measure the level of cell apoptosis. It is important to point out that more apoptotic cells does NOT mean less cell viability. This is because non-viable cells (dead cells) are derived from different types of cell death including type I (apoptosis), type II (autophagy), type III (necrosis) [37] along with contributions from various mechanisms of caspase-independent cell death [38]. Thus it is not possible to measure cell viability based on information derived only from apoptosis because apoptosis constitutes just one of many different types cell death already known to occur in-vitro or in-vivo. However, it is possible that increase of viable cell number may be due to an increase in cell division induced by high glucose.

It is of great interest to study the molecular mechanism involved in Müller cell response to high glucose treatment and glucose deprivation. Previous studies suggest that elevated levels of VEGF in Müller cells in various glucose conditions may be related to intracellular calcium, hypoxia inducible factor, ERK ½ pathway and others [33, 36, 39]. It is also not clear if VEGF secretion plays an essential role in the glucose induced changes in Müller cell viability observed in the present study. Nevertheless, Müller cell derived VEGF plays an important role in neovascularization and vascular damage in diabetic retinopathy. Therefore, further studies are required to understand the molecular action of high glucose to increase Müller cell viability and inhibit VEGF secretion.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the RCMI Program from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (G12MD007591) at the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Limb and Dr. Sarthy for their gift of human and rat Müller cell lines and Ms Jessica Buikema for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Roy MS, Klein R, O'Colmain BJ, Klein BE, Moss SE, et al. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adult type 1 diabetic persons in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):546–551. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Davis MD, DeMets DL. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(4):520–526. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030398010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.el Haddad OA, Saad MK. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy among Omani diabetics. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(8):901–906. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.8.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu J, Wei WB, Yuan MX, Yuan SY, Wan G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: the Beijing Communities Diabetes Study 6. Retina. 2012;32(2):322–329. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821c4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis MD, Fisher MR, Gangnon RE, Barton F, Aiello LM, et al. Risk factors for high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy and severe visual loss: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report #18. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(2):233–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tam J, Dhamdhere KP, Tiruveedhula P, Lujan BJ, Johnson RN, et al. Subclinical capillary changes in non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89(5):E692–703. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182548b07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogan DG, Toussaint D, Kuwabara T. Retinal vascular patterns IV. Diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1961;66(3):366–378. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1961.00960010368014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engerman RL. Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes. 1989;38(10):1203–1206. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.10.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li WY, Zhou Q, Tang L, Qin M, Hu TS. Intramural pericyte degeneration in early diabetic retinopathy study in vitro. Chin Med J (Engl) 1990;103(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishibashi T, Murata T, Kohno T, Ohnishi Y, Inomata H. Peripheral choriovitreal neovascularization in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: histopathologic and ultrastructural study. Ophthalmologica. 1999;213(3):154–158. doi: 10.1159/000027411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford TN, Alfaro DV, 3rd, Kerrison JB, Jablon EP. Diabetic retinopathy and angiogenesis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2009;5(1):8–13. doi: 10.2174/157339909787314149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simo R, Carrasco E, Garcia-Ramirez M, Hernandez C. Angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2(1):71–98. doi: 10.2174/157339906775473671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neely KA, Gardner TW. Ocular neovascularization: clarifying complex interactions. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(3):665–670. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65607-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valiatti FB, Crispim D, Benfica C, Valiatti BB, Kramer CK, et al. [The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis and diabetic retinopathy]. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2011;55(2):106–113. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302011000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56(4):549–580. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LE, Shen W, Perruzzi C, Soker S, Kinose F, et al. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent retinal neovascularization by insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Nat Med. 1999;5(12):1390–1395. doi: 10.1038/70963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor and the regulation of angiogenesis. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2000;55:15–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagineni CN, Kommineni VK, William A, Detrick B, Hooks JJ. Regulation of VEGF expression in human retinal cells by cytokines: implications for the role of inflammation in age-related macular degeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(1):116–126. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidro EK, Gee S, Unda R, Ma JX, Tsin A. Glucose and TGF β2 Modulate the Viability of Cultured Human Retinal Pericytes and Their VEGF Release. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33(11):984–993. doi: 10.1080/02713680802450976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heimsath EG, Jr, Unda R, Vidro E, Muniz A, Villazana-Espinoza ET, et al. ARPE-19 cell growth and cell functions in euglycemic culture media. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31(12):1073–1080. doi: 10.1080/02713680601052320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adamis AP, Shima DT, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Brown LF, et al. Synthesis and secretion of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193(2):631–638. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aiello LP, Northrup JM, Keyt BA, Takagi H, Iwamoto MA. Hypoxic regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in retinal cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(12):1538–1544. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100120068012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simorre-Pinatel V, Guerrin M, Chollet P, Penary M, Clamens S, et al. Vasculotropin-VEGF stimulates retinal capillary endothelial cells through an autocrine pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35(9):3393–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu M, Amano S, Miyamoto K, Garland R, Keough K, et al. Insulin-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(13):3281–3286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoi M, Yamagishi SI, Takeuchi M, Ohgami K, Okamoto T, et al. Elevations of AGE and vascular endothelial growth factor with decreased total antioxidant status in the vitreous fluid of diabetic patients with retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(6):673–675. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.055053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichenbach A, Bringmann A. New functions of Muller cells. Glia. 2013;61(5):651–678. doi: 10.1002/glia.22477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang JJ, Zhu M, Le YZ. Functions of Muller cell-derived vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic retinopathy. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(5):726–733. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i5.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bai Y, Ma JX, Guo J, Wang J, Zhu M, et al. Muller cell-derived VEGF is a significant contributor to retinal neovascularization. J Pathol. 2009;219(4):446–454. doi: 10.1002/path.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Wang D, Ye F, Hu DN, Liu X, et al. Elevated cell proliferation and VEGF production by high-glucose conditions in Muller cells involve XIAP. Eye. 2013;27(11):1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rungger-Brandle E, Dosso AA, Leuenberger PM. Glial reactivity, an early feature of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(7):1971–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Limb GA, Jayaram H. Regulatory and pathogenic roles of Müller glial cells in retinal neovascular processes and their potential for retinal regeneration. Experimental Approaches to Diabetic Retinopathy. Frontier in Diabetes. 2010;20:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang XL, Tao Y, Lu Q, Jiang YR. Apelin supports primary rat reti nal Müller cells under chemical hypoxia and glucose deprivation. Peptides. 2012;33(2):298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Zhao SZ, Wang PP, Yu SP, Zheng Z, et al. Calcium mediates high glucose-induced HIF-1alpha and VEGF expression in cultured rat retinal Muller cells through CaMKII-CREB pathway. Acta pharmacol Sin. 2012;33(8):1030–1036. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ke M, Hu XQ, Ouyang J, Dai B, Xu Y. The effect of astragalin on the VEGF production of cultured Muller cells under high glucose conditions. Biomed Mater Eng. 2012;22(1-3):113–119. doi: 10.3233/BME-2012-0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mu H, Zhang XM, Liu JJ, Dong L, Feng ZL. Effect of high glucose concentration on VEGF and PEDF expression in cultured retinal Muller cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36(8):2147–2151. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye X, Ren H, Zhang M, Sun Z, Jiang AC, et al. ERK1/2 signaling pathway in the release of VEGF from Muller cells in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(7):3481–3489. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berghe TV, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(2):135–147. doi: 10.1038/nrm3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroemer G, Martin SJ. Caspase-independent cell death. Nat Med. 2005;11(7):725–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks SE, Gu X, Kaufmann PM, Marcus DM, Caldwell RB. Modulation of VEGF production by pH and glucose in retinal Muller cells. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17(9):875–882. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.9.875.5134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]