Abstract

Background

Autograft and allograft transplantation are used to prompt the regeneration of axons after nerve injury. However, the poor self-regeneration caused by the glial scar and growth inhibitory factors after neuronal necrosis limit the efficacy of these methods. The purpose of this study was to develop a new chitosan porous scaffold for cell seeding.

Material/Methods

The bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) and tissue-engineered biomaterial scaffold compound were constructed and co-cultured in vitro with the differentiated BMSCs of Wistar rats and chitosan scaffold in a 3D environment. The purity of the third-generation BMSCs culture was identified using flow cytometry and assessment of induced neuronal differentiation. The scaffolds were prepared by the freeze-drying method. The internal structure of scaffolds and the change of cells’ growth and morphology were observed under a scanning electron microscope. The proliferation of cells was detected with the MTT method.

Results

On day 5 there was a significant difference in the absorbance value of the experimental group (0.549±0.0256) and the control group (0.487±0.0357) (P>0.05); but on day 7 there was no significant difference in the proliferation of the experimental group (0.751±0.011) and the control group and (0.78±0.017) (P>0.05).

Conclusions

Tissue engineering technology can provide a carrier for cells seeding and is expected to become an effective method for the regeneration and repair of nerve cells. Our study showed that chitosan porous scaffolds can be used for such purposes.

MeSH Keywords: Adult Stem Cells, Bone Marrow Cells, Tissue Engineering

Background

Stroke and central nervous system injury have been topics of interest in neuroscience research. Autograft and allograft transplantation were used to prompt the regeneration of axons after nerve injury. However, the poor self-regeneration caused by the glial scar and growth inhibitory factors after neuronal necrosis limited the efficacy of these methods, and it appeared that these techniques were not promising. In recent years, with the development of biological tissue engineering technology, the auxiliary repair of CNS damage using biocompatible materials has become one of the most promising methods for these patients [1,2]. In biocompatible materials, the seed cells and scaffold materials are fundamental elements. BMSC is a kind of pluripotent adult stem cell, which can be directionally induced and differentiate to nerve-like cells. It has wide potential application in the transplantation of CNS cells [3,4]. As a commonly used scaffold material in tissue engineering, chitosan had many advantages, such as strong biodegradability, low antigenicity, good biocompatibility, and no pyrogen reaction [5,6]. In the present study we explored the biocompatibility of co-cultured BMSCs and self-made absorbable chitosan porous scaffolds. The transplantation of cell-scaffold compound into the CNS may aid in the regeneration of nerve cells and recovery of nerve function.

Material and Methods

Animals

Healthy male Wistar rats at SPF level, aged 3 weeks and weighing about 100 g, were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of the Medical Institute of Xi’an Jiaotong University. The experiment was carried out in the Central Laboratory of Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital.

The animals were maintained on a 12:12 h light: dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal care facility with free access to food and water. The facility was fully accredited by the Chinese Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical Institute of Xi’an Jiaotong University. The work described in the article was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving animals.

Isolation and culture of BMSCs

The primary BMSCs were isolated from the rats’ forelimbs and cultured using the whole-bone marrow adherent culture method. In brief, the rats were anesthetized and bone marrow plugs were extruded from the bone marrow cavity. Flushing was done with serum-free DMEM/F12 medium (HyClone, USA), collected in sterile tubes and centrifuged. Subsequently, the fat and supernatant were discarded, and the resuspended cells at a density of 1×106/mL were incubated in monolayer in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (PBS) until 90% confluent. The cells were placed in a CO2 incubator (NAPCO Company, USA) with 5% CO2 at 95% humidity and 37°C for 48 h. Culture medium was replaced at 3-day intervals. Pre-plating for in the first 2 passages eliminated any fibroblasts remaining in the culture. When the cultured cells reached 80–90% confluence, they were passaged with 0.25% trypsin and expanded until the 3rd passage.

Identified phenotypic characterization and neuronal differentiation induction

One-half of the purity of the third-generation (P3) cells was identified using flow cytometry by detecting the expression of the specific cell surface marker. Another group of P3 BMSCs were incubated in neural differentiation medium (100 μg/mL mecobalamin + 10%FBS+ DMEM/F12) for 7–9 days and the medium was replaced every 2 days. We took some of the neural-induced BMSCs to verify the neuronal differentiation. The expression of heavy neurofilaments (NF-H) was detected using DAB immunohistochemical staining method, in which rat monoclonal antibody [NF-01] to 200 kDa heavy neurofilaments was used.

Preparation and detection of chitosan porous scaffolds

Chitosan porous scaffolds were obtained via a freeze-drying technique. Briefly, 1 ml of 2% chitosam-acetic acid solution in 24-well plate was keep at 4°C for 6 h and then at −25°C overnight. The next day, it was dried in a freeze-drying machine at −75°C for 24 h. Then, 1 ml of 0.1 M NaOH was added in each well for hydration for 20 min and dried again with the freeze-drying machine. Finally, the powder (or pellet) was immersed in 75% ethanol for 30 min and rinsed thoroughly with PBS 5 times before being used for cell culture.

Detection of the porosity of chitosan scaffolds

The porosity was detected by using the ethanol alternative method. The calculation formula of porosity was: P=(V1−V3)/V×100%; P refers to the porosity of the chitosan porous scaffold, V1 is the total volume of ethanol, V3 is the left ethanol volume after removing the chitosan porous scaffold, and V is the total volume of the scaffold. V=(V2−V1)+(V1−V3)=V2−V3; V2 is the total volume of the chitosan porous scaffold and ethanol in vacuum without escape of gases, “V2−V1” is the volume of chitosan porous scaffold, and “V1−V3” is the porous volume of the chitosan porous scaffold.

Characterization of chitosan porous scaffolds

The chitosan was cut into small pieces and rinsed repeatedly with PBS, and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (GA) and 1% osmium tetroxide fixed liquid (OSO4) at 4°C for 2 h. After gradient ethanol dehydration, the scaffold was dried using the critical point drying apparatus, coated with gold ions by sputtering method, and then was observed with a scanning electron microscope.

Co-culture and observation of chitosan porous scaffold and BMSCs

The chitosan porous scaffold was taken out from DMEM/F12 complete medium and cut into 5.0×5.0×3.0 mm blocks on a super net platform, and put in the 24-well culture plate. At 7 days after neural induction, we added 1 ml of 1×106/mL P3 BMSCs suspension to each well and cultured them in a cell culture incubator for 30 min, with gentle agitation every 15 min, after which 3 ml of complete medium was added in each well. After culturing for 48 h, the growth of BMSCs on scaffold was observed with an inverted microscope and a scanning electron microscope.

Proliferation and cytotoxicity of BMSCs on chitosan porous scaffold was detected using MTT method, and 1000 cells were seeded in each scaffold. The scaffolds were placed in 96-well plates. During the culturing, the culture medium was changed every 2 days. The culturing was stopped on day 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 after inoculation, when 200 μl of 5 mg/mL MTT serum-free DMEM/F12 culture medium was added in 4 wells of the experimental group (BMSCs + chitosan porous scaffold + culture medium) and the control group (BMSCs + culture medium). Four hours later, the suspension liquid was discarded and 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added for culture in for 15 min. Cells were oscillated on a shaking table at low speed for l5 min to allow the complete dissolution of crystals. The absorbance values were detected 4 times with an enzyme-labeled instrument to count the mean value for 5 consecutive days. A 490-nm wavelength was chosen and the zero hole was set at the same time as the control.

Statistical analysis

SPSS13.0 statistical software was used for analysis. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, the comparison among groups was detected with independent samples t-test, with an inspection level of α=0.05.

Results

Characterization of BMSCs

Identification of BMSCs

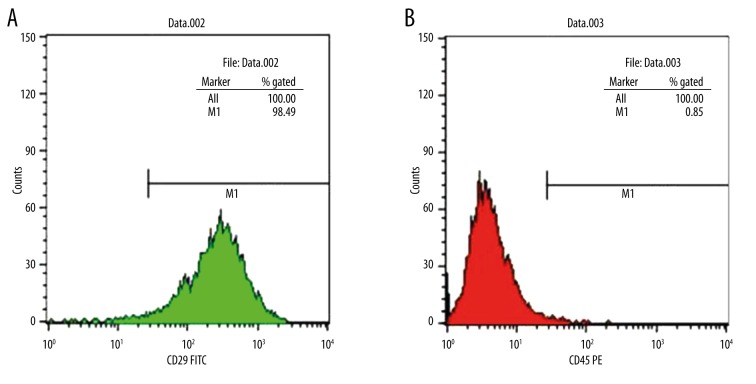

Consistent with previous studies, the high expression of the non-hematopoietic marker CD29 confirmed the purity level of the mesenchymal stem cells. Additionally, CD45, a hematopoietic marker, presented a low expression. As shown in Figure 1, the CD29-positive rate of the isolated BMSCs was 98.49%, while the CD45-positive rate was only 0.85%. At the same time, CD45 is a positive marker of hematopoietic stem cell, which should not be primarily expressed in BMSC. These results indicated the high purity of the third generation of BMSCs.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of BMMSC. Fluorescent cell sorting of passage 3 BMMSCs employing monoclonal antibody CD29 (A) CD45 (B) directed against cell surface.

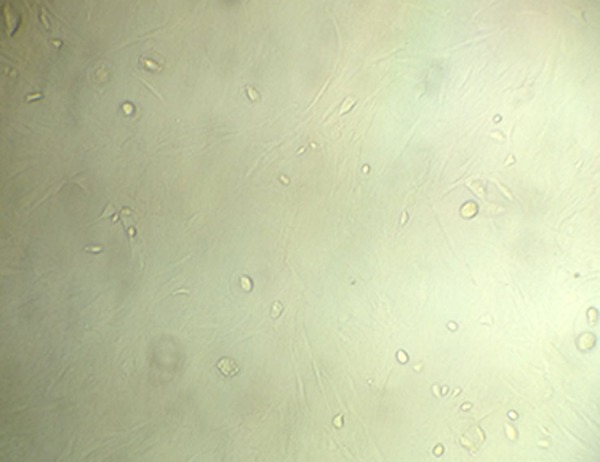

Morphological observation of BMSCs

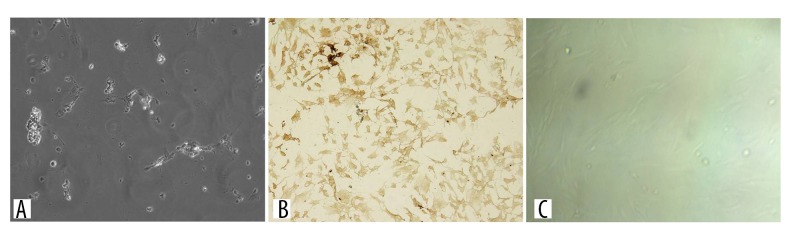

As shown in Figure 2, under the microscope the shape of the third-generation BMSCs cultured with the whole bone marrow adherent culture method was uniform, exhibiting a fibrous morphology, with significantly fewer mixed cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Morphology of the third-generation BMMSCs. The luminescent blotches or spots are the cells.

Induction of BMSCs with neuron-like morphology

BMSCs could be induced into neuron-like cells. When treated with differentiation medium, the BMSCs had a changed morphology and presented the appearance of neuronal cells. At 24 h after treatment, cells started to stretch and were slender, protruding from the protuberant, and began connecting with neighboring cells (Figure 3A). However, the expression of neuronal markers was not detected until 7 to 9 days after induction; after 7 days, the differentiated cells extended neurites and connected with each other. The phenotypical features of neurons generated from the cells were distinguishable, including unipolar or bi/multipolar elongations, forming a neural network-like structure. In addition, the cells expressed neuronal specific protein NF-H (Figure 3B). The control BMSCs were only cultured with 10%FBS+ DMEM/F12 medium, without neural inducer (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

(A) Microscopic pictograph showing the morphology of BMMSCs 24 h after induction. The cells started to stretch, became slender and protruded from the protuberant, and formed connections with neighboring cells. (B) IHC staining of neuron-specific protein NF-H of BMMSCs at 7 days after induction. The phenotypical features of neurons generated from the cells were distinguishable, including unipolar or bi/multipolar elongations, forming a neural network-like structure. (C) Control cells after 7 days without NF-H expression.

Characterization of biological chitosan porous scaffold

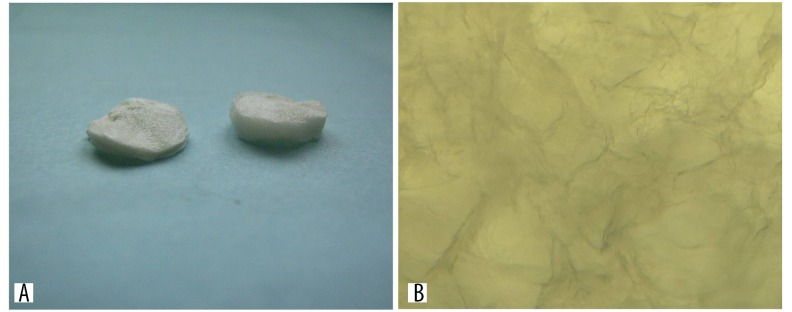

The general structure of the chitosan scaffold

Macroscopically, the prepared scaffold showed cavernous transformation, which could be cut into various shapes according to the actual condition (Figure 4A, 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) General form and (B) microstructure of the chitosan scaffold under microscope.

Determination of porosity

We added 1.08 mL ethanol (V1=1.08 mL) and a small piece of chitosan porous scaffold into a 1.5-mL cryopreserved tube to yield a liquid level scale of 1.10 mL (V2=1.10 mL). The liquid level scale was 0.90 mL (V3=0.90 mL) after removing the chitosan porous scaffold. The porosity of the chitosan porous scaffold was calculated according to Formula 1.

| (Formula 1) |

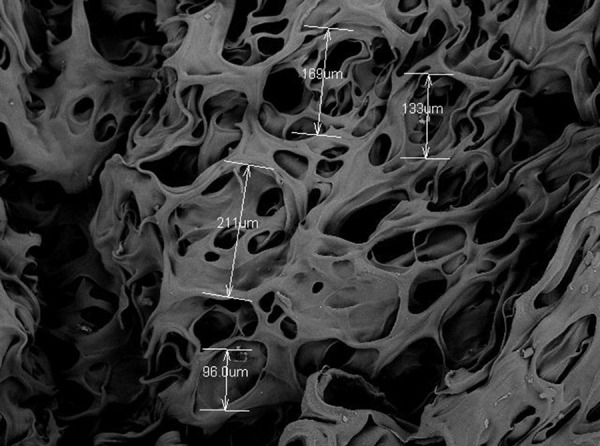

SEM observation of chitosan porous scaffold

Uniform 3D pores were observed on the cross-section of the chitosan porous scaffold under scanning electron microscopy. The chitosan porous scaffold had good connectivity and the pore size was 140±0.211 in aperture test via SEM (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Uniform 3D pores on the cross-section of the chitosan porous scaffold under scanning electron microscopy.

Characterization of chitosan porous scaffold and BMSCs co-culture

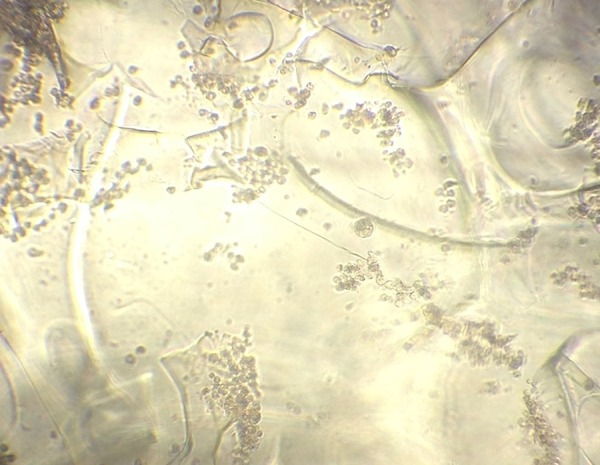

Observation under an inverted microscope

After the cultivation on the chitosan porous scaffold for 48 h, cells evenly spread into the pores, single or in clusters, on the scaffold. While shaking the culture plate, a few cells scattered at the bottom of the plate without drifting, which indicated the strong hydrophilicity and cell adsorption of the scaffold (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Observation of chitosan porous scaffold and BMSCs co-culture for 48 h under inverted microscope.

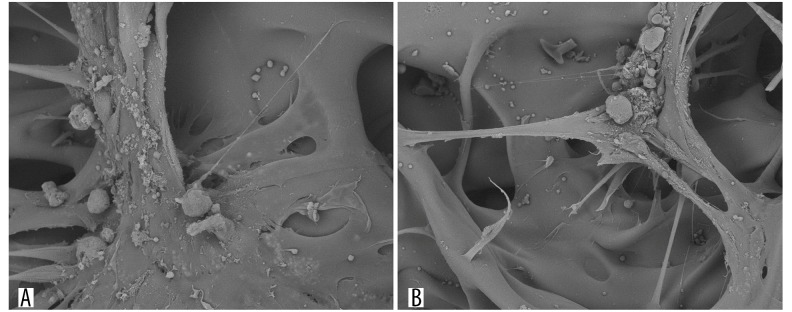

Observation under scanning electron microscope (SEM)

After the chitosan porous scaffold and induced BMSCs co-culture in vitro for 48 h, BMSCs with spindle shape and secreted extracellular matrix were widely distributed on the surface and pores of the chitosan porous scaffold. Many cells were distributed in several pores and the cells with spindle shape on the bottom were already present on the scaffold. Some of these cells secreted a large amount of extracellular matrix and adhered well to the scaffold, with pseudopodia extending into the scaffold. These results indicated the good growth condition of the BMSCs in the 3D culture environment (Figure 7A, 7B).

Figure 7.

Observation of chitosan porous scaffold and BMSCs co-culture for 48 h under scanning electronic microscope. (A) Wide spread of BMSCs on the surface and pores of the scaffold; (B) Bundle of cells with secreted extracellular matrix on the scaffold, with the pseudopods of some cells stretching out into the scaffold.

Proliferation and cytotoxicity of BMSCs on chitosan porous scaffold

We further characterize the proliferation of these BMSCs on the scaffold. On day 3 after co-culture, there was no significant difference in the absorbance value of the experimental group and the control group (P>0.05); on day 5, there was no significant difference in the absorbance value of the experimental group and the control group (P>0.05); on day 7, there was no significant difference in the proliferation of the experiment group and the control group (P>0.05). In general, the growth law of cells in the 2 groups was similar, which showed strong proliferation activity after the third day (Table 1). Then, the growth of cells significantly accelerated many-fold until the logarithmic growth phase. At 1 week after culture, the growth of BMSCs slowed. The chitosan porous scaffold had no obvious inhibition effect on BMSCs.

Table 1.

The proliferation of BMSCs on different days.

| Experimental group | Control group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | 0.489±0.013 | 0.503±0.009 | P>0.05 |

| Day 5 | 0.549±0.0256 | 0.487±0.0357 | P>0.05 |

| Day 7 | 0.751±0.011 | 0.78±0.017 | P>0.05 |

Discussion

Studies from basic and clinical trials have proved that, as a kind of scaffold carrier for tissue engineering, chitosan can promote wound healing, scar absorption, slow-releasing of drugs [7,8], regeneration and repair of nerve tissue [9,10], and prevent bacterial growth and inflammation. Chitosan also shared similarities with another kind of biological macromolecule polymer – amino polysaccharide – which is the main structure of extracellular matrix [6,11,12]. Because of its good affinity to the nerve cells, it was reported that it could significantly promote the growth of the spinal cord neurons and surrounding nerves [13]. Some Chinese studies on chitosan and retinal nerve cells reported that chitosan with different proportions could significantly promote retinal nerve cell growth in Wistar rats. To support cell proliferation, the ideal biological scaffold should have good histocompatibility, biodegradability, appropriate pore size, and porosity. These characteristics are the key points which can directly affect cell adhesion, growth, and migration. Thus, the materials should have multiple pores, connectivity, and aperture at least 50 μm and 70~90% porosity to provide enough space for cell growth [14]. At present, the techniques used for fabrication of chitosan porous scaffold include solution casting-particle filtration, freeze-drying/phase separation technique, and rapid prototyping technology. As high temperature can affect the biological materials and influence its performance, in our study the freeze-drying method was used [15]. Based on the principle of vacuum distillation of the deep-freezing solvent, lyophilization is widely utilized to prepare porous scaffolds. It can avoid the damage of high temperature to the bioactive molecules on the surface of the scaffold and can remove the organic solvent added into the samples (pore reagent) to ensure porous mesh structure. Therefore, the biologic activity of the materials could be well-maintained with intact biological characteristics [16,17]. Amado et al. prepared 3 types of chitosan membranes. Their results showed that the best condition of the membrane, which can significantly promote the regeneration and functional recovery of damaged axonal nerve cells, was with the surface porosity of 90% and aperture of about 110 μm [18]. In the present study, the porosity of the chitosan porous scaffold prepared with the freeze-drying technology was 90% and the aperture was 80–200 μm. The relatively uniform space and good connectivity fully met the requirements for cell growth.

In the current study, the BMSCs isolated from rat limbs achieved high purity in the third generation and proliferated well in vitro. BMSCs have unique advantages in promoting nerve regeneration. Our data also demonstrated that after induction, the BMMSCs differentiated into neuron-like cells. These results suggest BMSCs would be good sources for transplantation.

During the monolayer culture period, the contact inhibition among cells inhibited cell growth and proliferation. In contrast, the cell/scaffold complex construction can provide a 3D environment of nutrition absorption and growth metabolism. They are conducive to cell adhesion and growth and avoid cell loss [19]. In the current study, by using a scanning electronic microscope, we found good growth of BMSCs on the scaffold in vitro after co-culturing for 48 h. We found uniform distribution of cells on the surface of the scaffold and in pores, as well as adhesion of BMSCs, secretion of extracellular matrix adhered on the scaffold surface, massive cells in pores, and adhesion of some base cells in spindle form (they did not easily fall off), as well as good hydrophilicity. Moreover, the MTT test indicated that the scaffold had no effect on cell proliferation, although we cannot prove these induced cells maintain neuronal function. Our results show that BMSCs have good biocompatibility with the chitosan porous scaffold.

Conclusions

Tissue engineering technology can provide carrier for cell seeding, and is expected to become an effective method for the regeneration and repair of nerve cells. Our study showed the chitosan porous scaffolds can be used for this purpose. However, this research was based on rats; therefore, further study is needed before our conclusions can be extended to humans. Moreover, further research should be carried out to control degeneration of the chitosan porous scaffold, as well as to explore related factors and the mechanism by which the proliferation, migration, and differentiation occur.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there were no conflicts of interest in this report.

References

- 1.Uchida H, Morita T, Niizuma K, et al. Transplantation of unique subpopulation of fibroblasts, muse cells, ameliorates experimental stroke possibly via robust neuronal differentiation. Stem Cells. 2016;34:160–73. doi: 10.1002/stem.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocamonde B, Paradells S, Garcia Esparza MA, et al. Combined application of polyacrylate scaffold and lipoic acid treatment promotes neural tissue reparation after brain injury. Brain Inj. 2016;10:1–9. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1091505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuroda S, Shichinohe H, Houkin K, et al. Autologous bone marrow stromal cell transplantation for central nervous system disorders – recent progress and perspective for clinical application. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2011;7(1):2–13. doi: 10.46582/jsrm.0701002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen Q, Yin Y, Xia QJ, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells promote neuronal restoration in rats with traumatic brain injury: Involvement of GDNF regulating BAD and BAX signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38:748–62. doi: 10.1159/000443031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen ZS, Cui X, Hou RX, et al. Tough biodegradable chitosan-gelatin hydrogels via in situ precipitation for potential cartilage tissue engineering. RSC Advances. 2015;5:55640–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Zheng X, Zhang C, et al. Antigen-conjugated n-trimethylaminoethylmethacrylate chitosan nanoparticles induce strong immune responses after nasal administration. Pharm Res. 2015;32:22–36. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1441-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang R, Li W, Lv X, et al. Biomimetic LBL structured nanofibrous matrices assembled by chitosan/collagen for promoting wound healing. Biomaterials. 2015;53:58–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee BY, Li CW, Wang GJ. Nanoporous anodic aluminum oxide tube encapsulating a microporous chitosan/collagen composite for long-acting drug release. Biomedical Physics & Engineering Express. 2015;1:045004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andelic N. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:28–29. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nawrotek K, Tylman M, Rudnicka K, et al. Chitosan-based hydrogel implants enriched with calcium ions intended for peripheral nervous tissue regeneration. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;136:764–71. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulbake A, Jain SK. Chitosan: A potential polymer for colon-specific drug delivery system. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9:713–29. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.682148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santander-Ortega MJ, Peula-Garcia JM, Goycoolea F, Ortega-Vinuesa JL. Chitosan nanocapsules: Effect of chitosan molecular weight and acetylation degree on electrokinetic behaviour and colloidal stability. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;82:571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, et al. Influences of mechanical properties and permeability on chitosan nano/microfiber mesh tubes as a scaffold for nerve regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84:557–66. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danilevicius P, Georgiadi L, Pateman CJ, et al. The effect of porosity on cell ingrowth into accurately defined, laser-made, polylactide-based 3D scaffolds. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;336:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong L, Ao Q, Wang A, et al. Preparation and characterization of a multilayer biomimetic scaffold for bone tissue engineering. J Biomater Appl. 2007;22:223–39. doi: 10.1177/0885328206073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yada RY, Buck N, Canady R, et al. Engineered nanoscale food ingredients: Evaluation of current knowledge on material characteristics relevant to uptake from the gastrointestinal tract. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2014;13(4):730–44. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Wang X, Wu H, Liu R. Overview on biological activities and molecular characteristics of sulfated polysaccharides from marine green algae in recent years. Mar Drugs. 2014;12:4984–5020. doi: 10.3390/md12094984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amado S, Simões MJ, Armada da Silva PA, et al. Use of hybrid chitosan membranes and N1E-115 cells for promoting nerve regeneration in an axonotmesis rat model. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu CZ, Xia ZD, Han ZW, et al. Novel 3D collagen scaffolds fabricated by indirect printing technique for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;85:519–28. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]