Abstract

Exosomes are nano-sized (20–100 nm) vesicles released by a variety of cells and are generated within the endosomal system or at the plasma membrane. There is emerging evidence that exosomes play a key role in intercellular communication in ovarian and other cancers. The protein and microRNA content of exosomes has been implicated in various intracellular processes that mediate oncogenesis, tumor spread, and drug resistance. Exosomes may prime distant tissue sites for reception of future metastases and their release can be mediated by the tumor microenvironment (e.g., hypoxia). Ovarian cancer-derived exosomes have unique features that could be leveraged for use as biomarkers to facilitate improved detection and treatment of the disease. Further, exosomes have the potential to serve as targets and/or drug delivery vehicles in the treatment of ovarian cancer. In this review we discuss the biological and clinical significance of exosomes relevant to the progression, detection, and treatment of ovarian cancer.

Introduction

Exosomes are membrane-enclosed vesicles released by eukaryotic cells. Their size ranges from 20–100 nm and they can be released by normal or cancerous cells [1]. Recent studies suggest that microvesicle shedding is a highly regulated process that occurs in a spectrum of cell types and, more frequently, in tumor cells. Exosomes are detected in all human body fluids, including plasma, serum, saliva, urine and ascites [2, 3]. The composition and function of an exosome depends on its originating cell type [4]. Exosomes are particularly enriched in various tumor microenvironments [5], which may indicate a distinctive role in cancer progression and metastasis [6]. Tumor-derived exosomes are known to be involved in chemoresistance in many cancers, including ovarian cancer [7].

Exosomes are released in larger quantity from cancer cells (as compared to normal cells), a finding initially noted in patients with ovarian cancer [8]. Many different malignant disease sites may secrete exosomes, including breast, colon/rectum, brain, ovary [9], prostate, lung, and bladder cancer [10]. Exosomes interact with other cells and may serve as vehicles for the transfer of protein and RNA among cells. It has been reported that exosomes are internalized by ovarian tumor cells via various endocytic pathways and proteins from exosomes and cells are required for uptake [9]. Exosomes released from tumor cells are able to transfer a variety of molecules, including those that are cancer-specific, to other cells so as to manipulate their environment, making it more favorable for tumor growth and invasion [21]. They are known to mediate important regulatory role in a variety of cellular functions including immunomodulation, differentiation and antigen presentation [11]. Moreover, exosomes have been shown to play a role in the control of tumor growth, migration, invasion, inflammation, coagulation, and stem-cell renewal and expansion [12, 13]. In this review, we will discuss the state of the literature with respect to exosomes in ovarian cancer, with a focus on their role in tumor progression and their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Exosomes in ovarian cancer: an overview

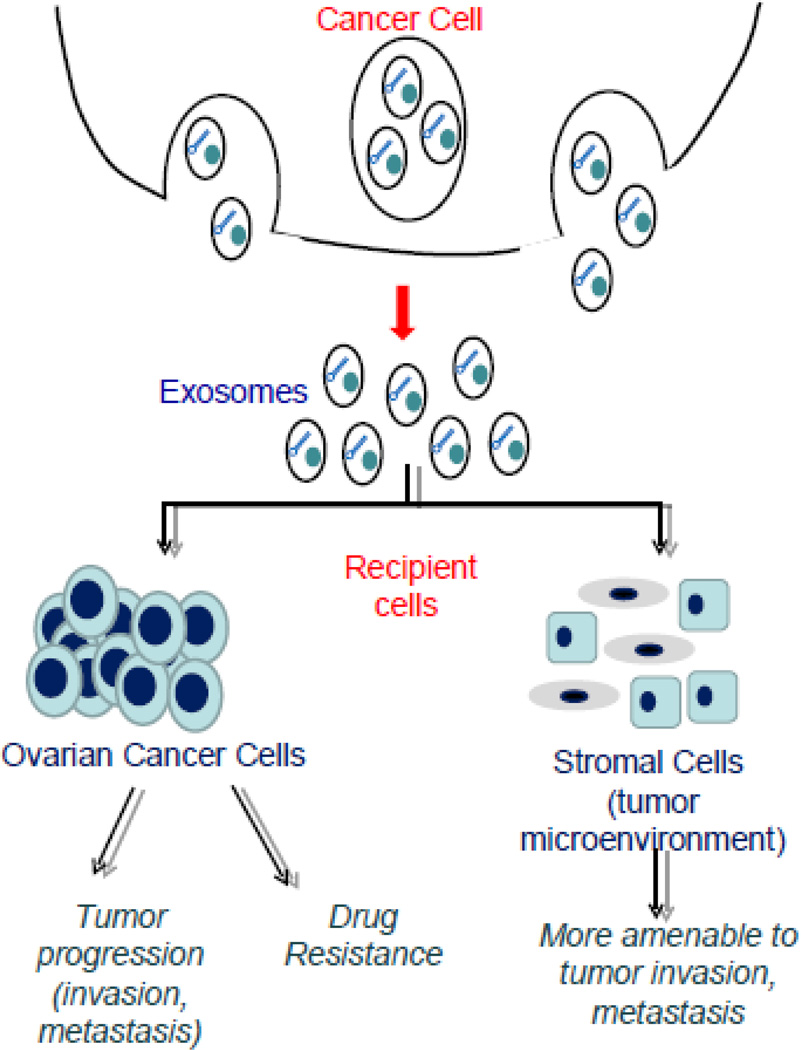

Ovarian cancer is the second-most commonly diagnosed gynecological malignancy, and is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer deaths among women in the United States. Each year, there are over 230,000 new cases and 150,000 deaths due to the disease reported worldwide [14]. The 5-year survival rate for ovarian cancer patients is approximately 45% [15]. The high mortality rate from this disease arises from the lack of an effective screening approach for early diagnosis, and drug resistance remains a major challenge. Platinum resistance is associated with an altered activation of cellular signaling pathways at the molecular level and cisplatin engulfed by exosomes and excreted from the cells [16]. Several research experiments have shown that exosomes are present in ovarian cancer patient’s plasma, serum and ascites [4, 17]. Exosomes released from ovarian cancer cells can be recognized and up-taken by other cells (cancer and/or stromal) to facilitate intercellular communication associated with tumor progression, metastasis and drug resistance (Fig. 1). Further, ovarian cancer-derived exosomes have the potential for serving as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the disease.

Fig 1.

Exosome release and impact after reception. Ovarian cancer cells release exosomes, which fuse recipient cells. Recipient cells can either be other ovarian cancer cells or stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment. The protein and microRNA content of the exosomes act on the recipient cells, promoting tumor progression and drug resistance.

Exosomal protein content contributing to malignancy in ovarian cancer

A variety of proteins can be found in or on ovarian cancer-derived exosomes; a number of these proteins may play a role in malignant behavior [4, 18]. Such proteins include membrane proteins (Alix, TSG 101) tetraspanins (CD63, CD37, CD53, CD81, CD82), heat-shock proteins (Hsp84/90, Hsc70), antigens (MHC I and II), as well as enzymes (phosphate isomerase, peroxiredoxin, aldehyde reductase, fatty acid synthase). These proteins are either associated with or involved in ovarian tumor progression and metastasis. In addition, exosomal proteins may play a role in treatment resistance. For example, annexin A3 can be detected in exosomes released from cisplatin-resistant cells; increased expression of the protein is associated with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer cells [19]. Such findings highlight a number of different ways in which the protein cargo of ovarian cancer exosomes could contribute to the biology of the disease. However, further research is needed to fully delineate the influence these proteins have over the malignant activity of ovarian cancer.

Exosomes interact with other cells and may serve as vehicles for the transfer of protein and RNA among cells [20]. Proteins transferred in this manner by tumor-derived exosomes may impact distant cell signaling or alter the tumor microenvironment in a way that promotes malignant growth and invasion. As an example, cancer exosomes can contain proteins that inhibit caspase activation and promote tumor proliferation, survival, and invasion [21]. Through exosomes, cancer cells may exchange functional signaling components (proteins) with other cells.

MicroRNA in ovarian cancer exosomes

MicroRNA is a small, non-coding RNA molecule that exhibit specific regulatory functions in cellular proliferation, differentiation, signal transduction, immune response, and carcinogenesis [22–24]. Pre-microRNA transcripts are synthesized by RNA polymerase II and processed consecutively by Drosha and Dicer endonucleases to form mature microRNA. Post-transcriptionally, microRNAs form imperfect base pairs with the 3’ untranslated region of mRNA. In doing so, microRNAs inhibit protein synthesis by repressing translation or degrading mRNA via the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [24, 25].

Cancer represents a state of cellular stress associated with a dependence on stress-induced signaling pathways [26]. The resulting activation of pro-survival and mitogenic pathways provides an opportunity for microRNAs to impact specific oncogenic or tumor suppressor phenotypes that are crucial for the progression or repression of cancer. However, microRNA expression has been shown to vary between various cell types and various cancers, making it difficult to identify canonical pathways for microRNA oncogenesis or tumor suppression [27]. Identification of microRNA dysregulation in the setting of specific cancers may have the potential to aid in clinical diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of progression [28].

It has been shown that exosomal microRNA contains specific nucleotide motifs that serve as signal sequences for the sumoylated RNA-binding protein hnRNPA2B1. This, in turn, allows for specific microRNAs to be sorted into exosomes in T cells [29]. The regulation of exosomal microRNA sorting is dependent on two factors: the abundance of microRNAs and the relative amount of endogenous mRNA targets of the microRNAs. Highly abundant microRNAs are preferentially sorted into both multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and exosomes. However, relative increases in the amount of endogenous target mRNA cause a “sponge” effect, where miRs localize at RNA targets and are thus excluded from the exosomal compartment [30].

Researchers have started to explore the association between exosomal microRNAs and their impact on various malignant processes. Recent studies have shown that exosomes can transmit resistance and alter the chemo-susceptibility in recipient sensitive cells by modulating various cellular processes such as cell cycle distribution and apoptosis [16]. Exosomal microRNAs also play important roles in tumorigenesis, growth, and metastasis. MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules with various functions and because they occur in both cells and in the circulation they also affect distant cells. Their role is a hotspot in recent research as they can provide new treatment strategies for tumor and as well for the tumor microenvironment. These regulate the target genes by binding to their noncoding regions in both physiological and pathological conditions that leads to disorders.

Exosomal microRNAs have been implicated in a number of processes in ovarian cancer, including oncogenesis, tumor spread, and drug resistance (Table 1) [31–34]. Regarding oncogenesis and tumor spread, miR-21 has been shown to target the tumor suppressor PDCD4 in serous ovarian carcinoma, playing a role in malignant transformation [22]. The overexpression of miR-21 and loss of PDCD4 is maintained in exosomes from ovarian serous carcinoma effusions, potentially contributing to tumor spread [35, 36].

Table 1.

Ovarian cancer-derived exosomal microRNAs

| Roles | MicroRNAs (miR) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic biomarkers | miR-21, miR-141, miR-184, miR-193b, miR- 200a,b,&c, miR-203, miR-205, miR-214, miR- 215 |

13, 22, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 |

| Malignant progression and poor prognosis |

miR21, miR-105, let-7 miR, miR-25, miR-29b, miR-100, miR-150, miR-187, miR-221, miR200, miR-335 |

31, 32, 36 |

| Therapeutics targets | miR-25, miR-29c, miR-101, miR-128, miR-141, miR-182, miR-200a, miR-506, miR-520d-3p |

31, 37 |

| Drug resistance | miR-106a, miR-130a, miR-221, miR-222, miR- 433, miR-591 |

34, 38 |

Exosomes and ovarian tumor microenvironment

Both ovarian tumor cells and their microenvironment contribute to tumor progression and metastasis. The tumor microenvironment is collection of stromal cells, soluble factors, extracellular matrix, and signaling molecules immediately adjacent to or surrounding a collection of cancer cells. Exosomes are predominantly enriched in hypoxic tumor microenvironments [37]. There is a consensus that exosomes guide the export of major types of proteins and transcription factors to the outer-cellular milieu [38]. Depending on the context, these proteins are either tumor promoters or tumor suppressors; their secretion via exosomes is expected to impact distant cell signaling or promote a niche that sustains tumor microenvironment receptive to future disease spread.

The high exosomal content of ascites seems to influence the ovarian cancer tumor microenvironment. Exosomes in malignant ascites are believed to play an important role in cell signaling and degradation of extracellular matrix proteins. Proteolytic enzymes have been isolated from exosomes, which suggests that exosomes promote ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion during metastasis [17]. MMP2 and MMP9 correlate with the gelatinolytic activity of exosomes isolated from ascites samples in patients with ovarian cancer [39], a finding that suggests that they may enhance cell migration and invasion in ovarian tumor metastasis.

Cancer exosomes are also considered potential mediators of pre-metastatic niche formation. A pre-metastatic niche is a site, not currently involved by tumor, that has been primed for receiving and supporting the future growth of a tumor metastasis [40]. There is growing evidence supporting a role for exosomes in this malignant process. A recent study showed that exosomes contribute to pre-metastatic niches in a process dependent on CD44v6, a marker of cancer-initiating cells in rat pancreatic adenocarcinoma [41]. Exosomes have also been found to enhance VEGFR1 expression and angiogenesis in the pre-metastatic niche when shed from CD105+ human renal cancer stem cells. Moreover, exosomes can alter stromal cells and fibroblasts to create a favorable tumor microenvironment. The mRNA from glioblastoma-derived exosomes and microRNAs from exosomes of breast, ovarian, and gastric cancer such as miR 210 and the miR let7 family have shown tumor promoting effects such as angiogenesis and metastasis [17]. It has also been shown that the release of exosomes into the omental vasculature might pave the way for the tumor progression and metastasis in the setting of ovarian cancer [42]. However, the exact role by which exosomes act on distant organs to help form a niche receptive to future metastasis remains largely unknown in ovarian cancer.

Intercellular crosstalk among cancer cells as well as between cancer cells and immune and stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment plays a large role in cancer development, the establishment of the mesenchymal state, and metastasis. Exosomes play a significant role in these processes. Inducers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) found in association with exosomes include TGFβ, TNFα, IL-6, TSG101, AKT, ILK1, β-catenin [43], hepatoma-derived growth factor, casein kinase II (CK2), annexin A2, integrin 3, caveolin-1, and matrix metalloproteinases [44]. For example, WNT carried by exosomes can act on a pathway so as to stabilize β-catenin which promotes a gene expression program that favors EMT [45]. Further, exosomal WNT can activate the release of soluble mediators such as IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, and MMP2, thereby promoting EMT in recipient cells [45]. Several other studies show that tumorderived exosomes can hijack MSCs to promote a prometastatic environment via activation of both Smad-dependent and -independent pathways. For instance, Exosomes from ovarian cancer were shown to induce adipose tissue-derived MSCs (ADSC) to exhibit the characteristics of CAFs, by increasing expression of TGFβ and activation of Smad-dependent and -independent pathways.

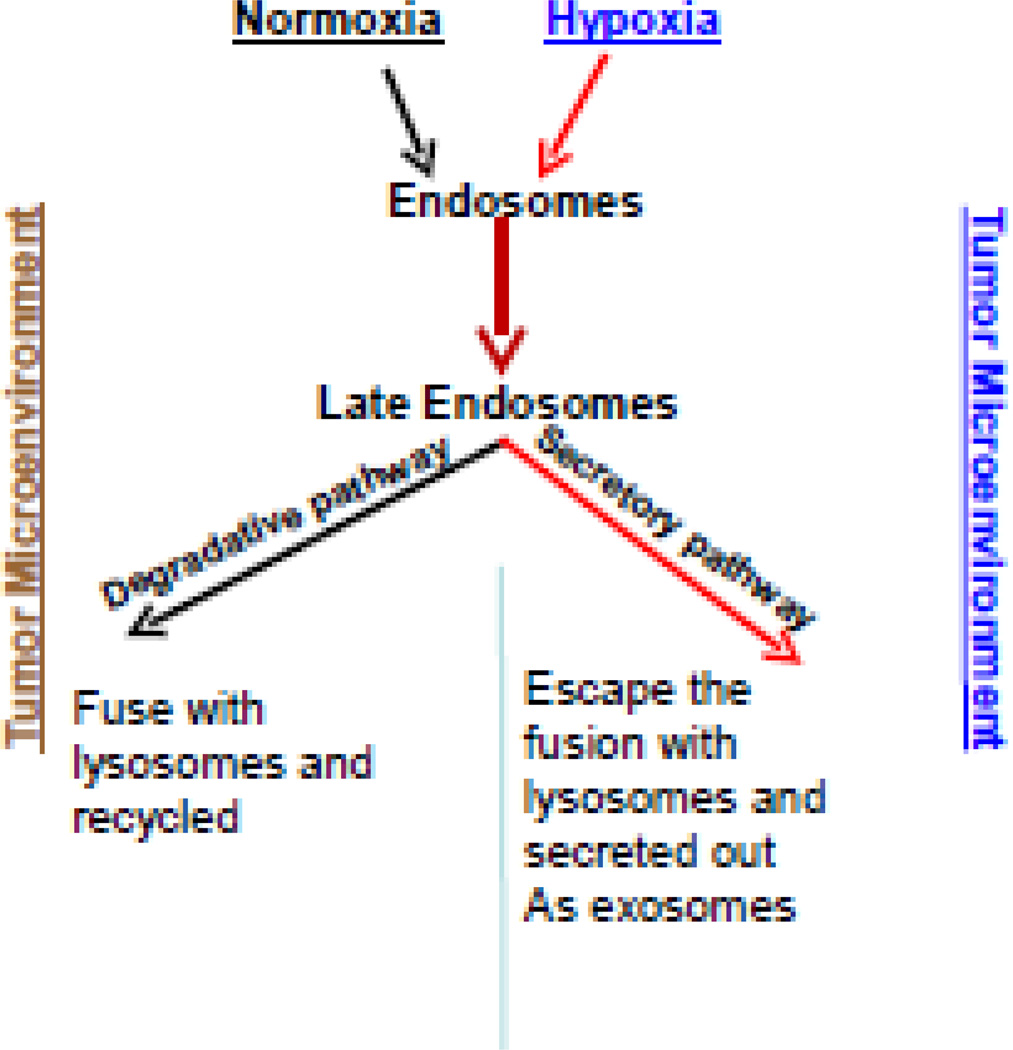

Hypoxia-mediated release of exosomes in the ovarian tumor environment

Ovarian tumors are hypoxic in nature, and growth under these conditions is known to activate a number of cellular signaling pathways that enhance proliferation and metastatic capacity. The hypoxic niche within a tumor harbors cells that are relatively chemoresistant compared to the majority of cells in the tumor [46]. It was recently documented that hypoxia promotes the secretion of various tumor-promoting factors and exosomes that can influence adjacent tissues in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 2) [37]. Further, our group has noted increased exosome release in hypoxic (compared to normoxic) environments in ovarian cancer cell lines (data not yet published). Therefore, either directly targeting hypoxia or the factors promoting this important phenomenon is an emerging form of therapy under investigation. A large family of membrane receptors, tetraspanins, has been proposed to have major function in exosome formation and release. For example, expression of the tetraspanins CD9 or CD82 induces exosomal sorting and secretion of β-catenin from cells, and tetraspanins CD63 and CD81 have been shown to bind components of the exosomal sorting machinery. Late endosomes/MVBs can be triggered to fuse with the cell surface and release their intraluminal vesicles. Along with several other proteins such as Flotillin2 and HSP70, the tetraspanins CD63 and CD9 are commonly used markers for exosomes [47]. However, the mechanism of exosome formation, secretion and uptake, as well as the physiological significance of exosomal content remain to be understood.

Fig 2.

Exosome release is influenced by hypoxic tumor microenvironment. In normoxic conditions, the late endosomes tend to be move and fuse with the lysosomes for further degradation and recycling. In hypoxic conditions, the late endosomes or the multivesicular bodies (MVB’s) are more likely to be assigned to a secretory pathway due to aberrant lysosomal trafficking and its altered phenotype causing them to move towards the periphery and fuse with the plasma membrane releasing the intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), or exosomes. The reason for the disposition of these to the secretory or degradative pathway is unknown which may involve the lysosomes and RAB proteins regulating the endosomal trafficking.

Exosomes as biomarkers in ovarian cancer

There is currently no recommended routine screening test for ovarian cancer in average-risk women. This is problematic as, even in a well-resourced country such as the United States, the majority of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer initially present at an advanced stage [15]. Thus, there is a need to evaluate alternative methods to assist in the early detection of ovarian cancer. Exosomes could be one such method. As carriers of complex biological information from their host cells, exosomes could theoretically be utilized in non-invasive diagnostic testing for cancer.

Tumor-derived exosomes are emerging as a new type of cancer biomarker as they can be obtained in all body fluids and have characteristic features that differentiate them from non-cancer exosomes [48]. Compared with biomarkers detected in conventional specimens, exosomal biomarkers provide similar or higher specificity and sensitivity attributed to their excellent stability [49].

Multiple components of a cancer exosome have the potential to serve as a cancer biomarker. The RNA content is of special interest as bare RNA in blood is rapidly degraded, but remains stable when protected inside an exosome [50]. Exosomes released by ovarian cancer have a microRNA “signature” that is a) similar to the microRNA profile of tumor cells, and b) unique compared to exosomes isolated from patients with benign ovarian tumors [22, 51]. Therefore, an evaluation of exosomal microRNA has the potential to be specific enough to be a diagnostic test—essentially a liquid biopsy. Of note, exosomal microRNA is experimental and has not been compared with other possible tumor-derived biosources (such as circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells) for efficacy as a “liquid biopsy” [52]. Proteins contained in, or expressed on, exosomes released by ovarian cancer cells are also under investigation for use in screening/diagnosis. As an example, claudin-4 proteins are released from ovarian cancer cells via exosomes. Claudin-4 obtained from exosomes in peripheral blood was shown to be present in 32 of 63 patients with ovarian cancer and one of 50 samples from healthy controls, representing a sensitivity of 51% and a specificity of 98% [53].

Exosomes also have the potential to serve as predictive and prognostic markers for response to treatment of ovarian cancer. For example, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer packages cisplatin in exosomes, exporting the drug from the cancer cells [54]. In addition, exosomes from platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells were recently shown to be capable of using the microRNA miR-21-3p to induce platinum resistance in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer cells [54, 55]. Further, exosomes can also contribute to resistance to paclitaxel, another first-line chemotherapeutic used in the treatment of ovarian cancer. miR-433 has been shown to mediate resistance to paclitaxel in A2780 ovarian cancer cells by inhibiting apoptosis and inducing cellular senescence [56]. Finally, exosomes can bind to, and sequester, immunotherapeutic agents. As an example, HER2-overexpressing cancer cells secrete exosomes that express HER2 on their surface and can bind/sequester the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab, thereby interfering with the activity of the drug [57]. It is therefore plausible that an analysis of the concentration, content, and activity of exosomes could be used as a predictive marker for response to treatment if one of these therapies is being considered.

From a prognostic standpoint, the exosomal proteins CD24, EpCAM, L1CAM, CD24, ADAM10, and EMMPRIN are associated with a poorer prognosis and/or greater likelihood of tumor progression, so may also be of value for treatment planning [4, 39].

While exosomes show great promise and versatility as biomarkers for ovarian cancer, there are several challenges that would need to be met prior to more widespread implementation. First, a standard method would need to be developed to consistently isolate cancer cell-derived exosomes from peripheral blood and separate them from normal, physiologic exosomes. Second, the clinical application of exosomes as biomarkers in ovarian cancer would have to show a positive impact on clinical outcomes such as improved early detection, progression-free survival, or overall survival rates. Third, exosome processing and analysis would need to be significantly less costly and time-consuming. Despite these challenges, exosomes have shown significant potential as future biomarkers for ovarian cancer; further research and development is warranted in this area.

Targeting exosomes to treat ovarian cancer

Attacking exosomal production and release

There are a number of options for targeting or exploiting exosomes in the treatment of ovarian cancer (Table 2). One such option is to block exosome production and secretion from cancer cells. Ceramide involved in production of exosomes; the sphingomyelinase inhibitor GW4869 depletes ceramide, reducing exosome formation [58]. In support of the ceramide concept, another group demonstrated that GW4869 reduced lung metastases in a murine lung carcinoma model; that result was partially reversed when cancer-derived exosomes were injected into the mice [59]. Secretion of exosomes is facilitated by H+/Na+ and Na+/Ca+ channels. Blocking those channels with dimethyl amiloride (DMA) was shown to decrease the immunosuppressive impact of exosomes and augment the antitumor effect of cyclophosphamide. In the same study, the authors found that amiloride, a drug taken for hypertension (and a derivative of DMA), also reduced exosome secretion and immunosuppressive action in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [60]. Another potential target is the Rab family of proteins, which play a role in the biogenesis of exosomes. Inhibition of Rab27a was found to inhibit exosome secretion [61].

Table 2.

Therapies with anticancer potential that target or utilize exosomes.

| Therapy | Mechanism of action | Type of data | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GW4869 | Sphingomyelinase inhibitor that depletes ceramide, a molecule used in the construction of exosomes |

Pre-clinical (in vitro, in vivo) |

49, 51 |

| Amiloride | Blocks H+/Na+ and Na+/Ca+ channels, which are involved in exosome secretion |

Pre-clinical (in vitro, in vivo, analysis of human samples) |

51 |

| Hemofiltration | Removes exosomes from circulation via a dialysis-like mechanism |

None yet. Concept based on a device used to reduce viral titers in patients. |

16 |

| Exosome- augmented immunotherapy |

|

|

|

| Exosome- encapsulated anti-neoplastics |

Anti-cancer compounds can be made more bioavailable when loaded into exosomes. Adding a targeting protein to such exosomes can further enhance anti-neoplastic activity. |

Pre-clinical (in vitro, in vivo) |

62, 68–70 |

Removal of exosomes from peripheral circulation

If exosomes are involved in tumor metastasis/progression, why not remove them? A hemofiltration device, the Hemopurifier (Aethlon Medical, San Diego, CA), has been developed to do just that, using a filter that contains fibers with a high affinity for exosomes [62]. When blood passes through the filter, the exosomes are selectively removed from the circulation using a dialysis-like mechanism. This could be beneficial in that there would be no risk of drug toxicity, as it is a non-pharmacological treatment. However, it is unknown whether this method will improve clinical outcomes. Other potential barriers to widespread implementation include monetary cost and the possible risk of removing non-cancer exosomes.

Exploiting exosomes to facilitate the treatment of ovarian cancer

Exosome-augmented immunotherapy

Exosomes are known to stimulate the immune system. For example, exosomes induce an antigen-specific response from MHC class II T cells. Based on that finding, there has been a push to develop treatments that utilize tumor-derived exosomes as antigen-presenting entities.

Several phase I trials have evaluated the role of exosome-mediated immunotherapy in other disease sites. A phase I trial was done in which 15 patients with metastatic melanoma were vaccinated with exosomes derived from dendritic cells that had been exposed to tumor cells. The vaccine was found to be feasible and safe. A partial response was noted in one patient [63]. Another phase I trial in 13 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer found that a vaccine derived from autologous dendritic cell-derived exosomes was well-tolerated and associated with long-term stability of disease in some patients [64]. Further, a phase I trial of 40 patients with advanced colorectal cancer found that treatment with autologous ascites-derived exosomes, when given with a granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, was able to induce an anti-tumor response by cytotoxic T lymphocytes [65].

Data on exosome-mediated immunotherapy ovarian cancer is scarce, but the concept is gaining traction. A group found that fusing the (typically poorly immunogenic) tumor-associated antigens CEA and HER2 to exosomes enhanced their immunogenicity in animal models [66]. At the time of this review, there is no active clinical trial involving exosome-based therapy for patients with ovarian cancer, but there is a specimen-collection study listed on clinicaltrials.gov evaluating the impact of exosomes on clinical outcomes in advanced ovarian cancer [identifier: NCT02063464].

Exosome-facilitated drug delivery

Exosomes have shown promise in improving solubility and reducing toxicity of cancer therapies. For example, incorporating curcumin (which has proven anti-neoplastic properties yet is limited by its poor solubility) into exosomes improves solubility, stability, and bioavailability of the compound [67]. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes loaded with doxorubicin and engineered to express a targeting protein were recently shown to inhibit breast cancer in vitro and in vivo, with reduced toxicity compared with native doxorubicin. Further, the anti-cancer activity of doxorubicin encapsulated in targeted exosomes was superior to that of free doxorubicin and doxorubicin delivered in untargeted exosomes [68].

Compared to synthetic drug carriers, exosomes may be especially useful due to their endogenous origin and role in intercellular communication. However, the complexity of this modality of drug delivery may serve as a barrier to large-scale clinical implementation. Important issues to address in exosome-based drug delivery include: choice of donor cell type, what to include as therapeutic cargo (small interfering RNAs, microRNAs, and/or medications), how to load the exosomes with this cargo, what targeting peptides to use on the exosome surface, and route of administration [69]. Synthetic production of exosome mimetics, by constructing liposomes that contain only the critical components of natural exosomes, might be a way to streamline some of these issues and permit more widespread clinical use [70].

Conclusions

The scientific understanding of exosomes’ contribution to malignant progression in a variety of disease sites has recently and dramatically expanded. Cancer exosomes have the ability to induce malignant behavior in non-cancer cells, prime distant tissues for reception of future metastases, and increase resistance to therapy in treatment-sensitive cancer cells. However, many questions remain regarding exosomes in cancer. For example, the tumor environment (e.g., hypoxia) appears to influence exosome release, but the mechanisms for this are largely unknown. In addition, the impact of exosomes on recipient cells needs to be further delineated and likely varies depending on the donor and receiver cell types.

For ovarian cancer, a disease that presents at an advanced stage for the majority of those afflicted, there is a great need for earlier detection. And with recurrent disease, developing more effective, targeted therapies will be essential in improving outcomes. Exosomes have shown promise as potential biomarkers to aid in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and may serve as targets of anti-cancer therapy. Many challenges would need to be met prior to large-scale clinical utilization of exosomes in the detection and treatment of ovarian cancer. However, their potential is exciting, and deserves further research and development.

Highlights.

Ovarian cancer-derived exosomes play significant roles in intercellular communication.

They impact tumor progression, metastasis, and drug resistance.

They have the potential to serve as biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and drug delivery vehicles.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by NCI RO1 grant – CA176078, Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (OCRF) awards to K.S & D.E.C. and OSU CCC internal grant to D.E.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement - The all authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Nickel W. Unconventional secretory routes: direct protein export across the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Traffic. 2005;6:607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuntoli RL, 2nd, Webb TJ, Zoso A, Rogers O, Diaz-Montes TP, Bristow RE, et al. Ovarian cancer-associated ascites demonstrates altered immune environment: implications for antitumor immunity. Anticancer research. 2009;29:2875–2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szajnik M, Derbis M, Lach M, Patalas P, Michalak M, Drzewiecka H, et al. Exosomes in Plasma of Patients with Ovarian Carcinoma: Potential Biomarkers of Tumor Progression and Response to Therapy. Gynecology & obstetrics. 2013;(Suppl 4):3. doi: 10.4172/2161-0932.S4-003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Runz S, Keller S, Rupp C, Stoeck A, Issa Y, Koensgen D, et al. Malignant ascites-derived exosomes of ovarian carcinoma patients contain CD24 and EpCAM. Gynecologic oncology. 2007;107:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutta S, Warshall C, Bandyopadhyay C, Dutta D, Chandran B. Interactions between exosomes from breast cancer cells and primary mammary epithelial cells leads to generation of reactive oxygen species which induce DNA damage response, stabilization of p53 and autophagy in epithelial cells. PloS one. 2014;9:e97580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv MM, Zhu XY, Chen WX, Zhong SL, Hu Q, Ma TF, et al. Exosomes mediate drug resistance transfer in MCF-7 breast cancer cells and a probable mechanism is delivery of P-glycoprotein. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014;35:10773–10779. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2377-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor DD, Homesley HD, Doellgast GJ. "Membrane-associated" immunoglobulins in cyst and ascites fluids of ovarian cancer patients. American journal of reproductive immunology : AJRI : official journal of the American Society for the Immunology of Reproduction and the International Coordination Committee for Immunology of Reproduction. 1983;3:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1983.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escrevente C, Keller S, Altevogt P, Costa J. Interaction and uptake of exosomes by ovarian cancer cells. BMC cancer. 2011;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welton JL, Khanna S, Giles PJ, Brennan P, Brewis IA, Staffurth J, et al. Proteomics analysis of bladder cancer exosomes. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2010;9:1324–1338. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000063-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valenti R, Huber V, Iero M, Filipazzi P, Parmiani G, Rivoltini L. Tumor-released microvesicles as vehicles of immunosuppression. Cancer research. 2007;67:2912–2915. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiteside TL. Tumour-derived exosomes or microvesicles: another mechanism of tumour escape from the host immune system? British journal of cancer. 2005;92:209–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. Tumour-derived exosomes and their role in cancer-associated T-cell signalling defects. British journal of cancer. 2005;92:305–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Ovary Cancer. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tickner JA, Urquhart AJ, Stephenson SA, Richard DJ, O'Byrne KJ. Functions and therapeutic roles of exosomes in cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:127. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shender VO, Pavlyukov MS, Ziganshin RH, Arapidi GP, Kovalchuk SI, Anikanov NA, et al. Proteome-metabolome profiling of ovarian cancer ascites reveals novel components involved in intercellular communication. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2014;13:3558–3571. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.041194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enriquez VA, Cleys ER, Da Silveira JC, Spillman MA, Winger QA, Bouma GJ. High LIN28A Expressing Ovarian Cancer Cells Secrete Exosomes That Induce Invasion and Migration in HEK293 Cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:701390. doi: 10.1155/2015/701390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin J, Yan X, Yao X, Zhang Y, Shan Y, Mao N, et al. Secretion of annexin A3 from ovarian cancer cells and its association with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer patients. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:337–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Rak J. Microvesicles: messengers and mediators of tumor progression. Cell cycle. 2009;8:2014–2018. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan S, Jutzy JM, Aspe JR, McGregor DW, Neidigh JW, Wall NR. Survivin is released from cancer cells via exosomes. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2011;16:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0534-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2008;110:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratner ES, Tuck D, Richter C, Nallur S, Patel RM, Schultz V, et al. MicroRNA signatures differentiate uterine cancer tumor subtypes. Gynecologic oncology. 2010;118:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniataki E, Mourelatos Z. A human, ATP-independent, RISC assembly machine fueled by pre-miRNA. Genes & development. 2005;19:2979–2990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo QJ, Samanta MP, Koksal F, Janda J, Galbraith DW, Richardson CR, et al. Evidence for antisense transcription associated with microRNA target mRNAs in Arabidopsis. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendell JT, Olson EN. MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell. 2012;148:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilabert-Estelles J, Braza-Boils A, Ramon LA, Zorio E, Medina P, Espana F, et al. Role of microRNAs in gynecological pathology. Current medicinal chemistry. 2012;19:2406–2413. doi: 10.2174/092986712800269362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villarroya-Beltri C, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Sanchez-Madrid F, Mittelbrunn M. Analysis of microRNA and protein transfer by exosomes during an immune synapse. Methods in molecular biology. 2013;1024:41–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-453-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squadrito ML, Baer C, Burdet F, Maderna C, Gilfillan GD, Lyle R, et al. Endogenous RNAs modulate microRNA sorting to exosomes and transfer to acceptor cells. Cell reports. 2014;8:1432–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang B, Peng P, Chen S, Li L, Zhang M, Cao D, et al. Characterization and proteomic analysis of ovarian cancer-derived exosomes. Journal of proteomics. 2013;80:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi M, Salomon C, Tapia J, Illanes SE, Mitchell MD, Rice GE. Ovarian cancer cell invasiveness is associated with discordant exosomal sequestration of Let-7 miRNA and miR-200. J Transl Med. 2014;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li SD, Zhang JR, Wang YQ, Wan XP. The role of microRNAs in ovarian cancer initiation and progression. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2240–2249. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorrentino A, Liu CG, Addario A, Peschle C, Scambia G, Ferlini C. Role of microRNAs in drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappellesso R, Tinazzi A, Giurici T, Simonato F, Guzzardo V, Ventura L, et al. Programmed cell death 4 and microRNA 21 inverse expression is maintained in cells and exosomes from ovarian serous carcinoma effusions. Cancer cytopathology. 2014;122:685–693. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaksman O, Trope C, Davidson B, Reich R. Exosome-derived miRNAs and ovarian carcinoma progression. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2113–2120. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King HW, Michael MZ, Gleadle JM. Hypoxic enhancement of exosome release by breast cancer cells. BMC cancer. 2012;12:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azmi AS, Bao B, Sarkar FH. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance: a comprehensive review. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2013;32:623–642. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller S, Konig AK, Marme F, Runz S, Wolterink S, Koensgen D, et al. Systemic presence and tumor-growth promoting effect of ovarian carcinoma released exosomes. Cancer letters. 2009;278:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peinado H, Lavotshkin S, Lyden D. The secreted factors responsible for pre-metastatic niche formation: old sayings and new thoughts. Seminars in cancer biology. 2011;21:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung T, Castellana D, Klingbeil P, Cuesta Hernandez I, Vitacolonna M, Orlicky DJ, et al. CD44v6 dependence of premetastatic niche preparation by exosomes. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1093–1105. doi: 10.1593/neo.09822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pradeep S, Kim SW, Wu SY, Nishimura M, Chaluvally-Raghavan P, Miyake T, et al. Hematogenous metastasis of ovarian cancer: rethinking mode of spread. Cancer cell. 2014;26:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramteke A, Ting H, Agarwal C, Mateen S, Somasagara R, Hussain A, et al. Exosomes secreted under hypoxia enhance invasiveness and stemness of prostate cancer cells by targeting adherens junction molecules. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2015;54:554–565. doi: 10.1002/mc.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felicetti F, Parolini I, Bottero L, Fecchi K, Errico MC, Raggi C, et al. Caveolin-1 tumor-promoting role in human melanoma. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2009;125:1514–1522. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K, Boutros M. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:1036–1045. doi: 10.1038/ncb2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCann GA, Naidu S, Rath KS, Bid HK, Tierney BJ, Suarez A, et al. Targeting constitutively-activated STAT3 in hypoxic ovarian cancer, using a novel STAT3 inhibitor. Oncoscience. 2014;1:216–228. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauschenberger L, Staar D, Thom K, Scharf C, Venz S, Homuth G, et al. Exosomal particles secreted by prostate cancer cells are potent mRNA and protein vehicles for the interference of tumor and tumor environment. The Prostate. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pros.23132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang MK, Wong AS. Exosomes: Emerging biomarkers and targets for ovarian cancer. Cancer letters. 2015;367:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang W, Peng P, Kuang Y, Yang J, Cao D, You Y, et al. Characterization of exosomes derived from ovarian cancer cells and normal ovarian epithelial cells by nanoparticle tracking analysis. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M, Rai AJ, Joel DeCastro G, Zeringer E, Barta T, Magdaleno S, et al. An optimized procedure for exosome isolation and analysis using serum samples: Application to cancer biomarker discovery. Methods. 2015;87:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R, Gaudio E, Santhanam R, et al. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2110–E2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209414109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karachaliou N, Mayo-de-Las-Casas C, Molina-Vila MA, Rosell R. Real-time liquid biopsies become a reality in cancer treatment. Annals of translational medicine. 2015;3:36. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.01.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li J, Sherman-Baust CA, Tsai-Turton M, Bristow RE, Roden RB, Morin PJ. Claudin-containing exosomes in the peripheral circulation of women with ovarian cancer. BMC cancer. 2009;9:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Safaei R, Larson BJ, Cheng TC, Gibson MA, Otani S, Naerdemann W, et al. Abnormal lysosomal trafficking and enhanced exosomal export of cisplatin in drug-resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2005;4:1595–1604. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pink RC, Samuel P, Massa D, Caley DP, Brooks SA, Carter DR. The passenger strand, miR-21-3p, plays a role in mediating cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Gynecologic oncology. 2015;137:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiner-Gorzel K, Dempsey E, Milewska M, McGoldrick A, Toh V, Walsh A, et al. Overexpression of the microRNA miR-433 promotes resistance to paclitaxel through the induction of cellular senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer medicine. 2015;4:745–758. doi: 10.1002/cam4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ciravolo V, Huber V, Ghedini GC, Venturelli E, Bianchi F, Campiglio M, et al. Potential role of HER2-overexpressing exosomes in countering trastuzumab-based therapy. Journal of cellular physiology. 2012;227:658–667. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pelosi G, Fabbri A, Bianchi F, Maisonneuve P, Rossi G, Barbareschi M, et al. DeltaNp63 (p40) and thyroid transcription factor-1 immunoreactivity on small biopsies or cellblocks for typing non-small cell lung cancer: a novel two-hit, sparing-material approach. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2012;7:281–290. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823815d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chalmin F, Ladoire S, Mignot G, Vincent J, Bruchard M, Remy-Martin JP, et al. Membrane-associated Hsp72 from tumor-derived exosomes mediates STAT3-dependent immunosuppressive function of mouse and human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:457–471. doi: 10.1172/JCI40483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nature cell biology. 2010;12:19–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb2000. sup pp 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marleau AM, Chen CS, Joyce JA, Tullis RH. Exosome removal as a therapeutic adjuvant in cancer. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:134. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Escudier B, Dorval T, Chaput N, Andre F, Caby MP, Novault S, et al. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (DC) derived-exosomes: results of thefirst phase I clinical trial. Journal of translational medicine. 2005;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morse MA, Garst J, Osada T, Khan S, Hobeika A, Clay TM, et al. A phase I study of dexosome immunotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of translational medicine. 2005;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dai S, Wei D, Wu Z, Zhou X, Wei X, Huang H, et al. Phase I clinical trial of autologous ascites-derived exosomes combined with GM-CSF for colorectal cancer. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2008;16:782–790. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hartman ZC, Wei J, Glass OK, Guo H, Lei G, Yang XY, et al. Increasing vaccine potency through exosome antigen targeting. Vaccine. 2011;29:9361–9367. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun D, Zhuang X, Xiang X, Liu Y, Zhang S, Liu C, et al. A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system: the anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2010;18:1606–1614. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tian Y, Jiang X, Chen X, Shao Z, Yang W. Doxorubicin-loaded magnetic silk fibroin nanoparticles for targeted therapy of multidrug-resistant cancer. Advanced materials. 2014;26:7393–7398. doi: 10.1002/adma.201403562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnsen KB, Gudbergsson JM, Skov MN, Pilgaard L, Moos T, Duroux M. A comprehensive overview of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles - endogenous nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1846:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kooijmans SA, Vader P, van Dommelen SM, van Solinge WW, Schiffelers RM. Exosome mimetics: a novel class of drug delivery systems. International journal of nanomedicine. 2012;7:1525–1541. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]