Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between periarterial neovascularization, development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV), and long-term clinical outcomes after heart transplantation.

Background

Proliferation of the vasa vasorum is associated with arterial inflammation. The contribution of angiogenesis to the development of CAV has been suggested.

Methods

Serial (baseline and 1-year post-transplant) intravascular ultrasound was performed in 102 heart transplant recipients. Periarterial small vessels (PSV) were defined as echolucent luminal structures <1 mm in diameter, located within 2 mm outside of the external elastic membrane. The signal void structures were excluded when they connected to the coronary lumen (considered as side branches) or could not be followed in ≥3 contiguous frames. The number of PSV was counted at 1-mm intervals throughout the first 50 mm of the left anterior descending artery, and PSV score was calculated as the sum of cross-sectional values. Patients with a PSV score increase ≥4 between baseline and 1-year post-transplant were classified as the “proliferative” group. Maximum intimal thickness was measured for the entire analysis segment.

Results

During the first year post-transplant, the proliferative group showed a greater increase in maximum intimal thickness (0.33±0.36 mm vs. 0.10±0.28 mm, p<0.001) and had a higher incidence of acute cellular rejection (50.0% vs. 23.9%, p=0.025) than the non-proliferative group. On Kaplan-Meier analysis, cardiac death-free survival rate over a median of 4.7 years was significantly lower in the proliferative group than in the non-proliferative group (hazard ratio=3.10, p=0.036).

Conclusions

The increase in PSV, potentially representing an angioproliferative response around the coronary arteries, was associated with early CAV progression and reduced survival after heart transplantation.

Keywords: cardiac allograft vasculopathy, neovascularization, intravascular ultrasound

Introduction

A number of studies have shown that proliferation of the vasa vasorum is related to arterial inflammation and plaque progression in atherosclerotic lesions. (1,2) While several kinds of special imaging techniques using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), such as contrast-enhanced IVUS, (3,4) have attempted to evaluate the vasa vasorum in vivo in the coronary arterial wall by detecting its blood flow, the relatively large vasa vasorum in the adventitia can be detected by orthodox grey-scale IVUS. (5) In heart transplant recipients, cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV), characterized by diffuse intimal thickening and luminal narrowing in the allograft coronary arteries, remains the major cause of long-term allograft failure. (6) Although the pathogenesis of CAV is distinct from native atherosclerosis, previous studies have suggested the contribution of angiogenesis to the development of intimal thickening in CAV. (7,8) Furthermore, a recent study using optical coherence tomography (OCT) suggested a relationship between proliferation of the adventitial vasa vasorum and development of CAV. (9) However, there are few detailed reports evaluating serial changes in the vasa vasorum and their impact on CAV progression. In addition, it remains unclear whether proliferation of the vasa vasorum has an impact on long-term clinical outcomes. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the association of periarterial neovascularization with early development of CAV and long-term clinical outcomes after heart transplantation, as assessed by serial IVUS analyses.

Methods

Study Population

Data were obtained from clinical and research databases on recipients of de novo heart transplants between January 2002 and March 2013 at Stanford University Medical Center. Recipients enrolled in this retrospective study were: 1) older than the age of 18 years; 2) clinically stable with a serum creatinine ≤2 mg/dL; 3) had not undergone a repeat transplantation; and 4) underwent serial pre-scheduled IVUS imaging with high-quality automated pullback, enabling complete volumetric IVUS analysis, at both baseline (4 to 6 weeks after the transplant procedure) and 1 year after transplantation. All recipients received standard immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids, an antiproliferative agent (rapamycin or mycophenolate mofetil) and a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus). Recipients were monitored for acute cellular rejection using right ventricular endomyocardial biopsies at scheduled intervals post-transplant: weekly during the first month, biweekly until the third month, monthly until the sixth month, and then at 9 and 12 months. Biopsies were graded according to the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation 2004 revised grading scale, and significant acute cellular rejection was defined as one or more episode(s) of grade of ≥2R during the first year post-transplant. (10,11) In addition, the degree of rejection was scored as 0R = 0, 1R = 1, 2R = 2, and 3R = 3, and maximum severity of rejection was determined as the highest score of any biopsy in each patient. A mean rejection score was also calculated as the sum of the score at each biopsy, divided by the total number of biopsies conducted during the first year after transplantation. Recipients were followed beyond the first year after transplantation, and the clinical endpoints examined were all-cause mortality, cardiac death, and re-transplantation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University Medical Center.

IVUS Imaging and Analysis

After intracoronary administration of nitroglycerin (200 µg), IVUS imaging was performed in a standard fashion using an automated 0.5 mm/second pullback with a commercially available imaging system 40-MHz IVUS catheter, Boston Scientific Corp., Marlborough, MA) at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Images were recorded for offline analysis of the first 50 mm of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD). Volumetric IVUS analysis was conducted at the Stanford University Cardiovascular Core Analysis Laboratory using validated software (echoPlaque; Indec Systems, Santa Clara, CA), and was blinded to clinical and angiographic information. Vessel, lumen and intimal (calculated as vessel minus lumen) areas were manually traced at 1-mm intervals throughout the first 50 mm of each LAD. Maximum intimal thickness in each cross-section was then calculated. Vessel, lumen and intimal volumes were calculated using Simpson’s method and standardized as volume index (VI, volume/length, mm3/mm). Percent intimal volume was calculated as intimal volume divided by vessel volume (percent), and maximum intimal thickness of the entire segment (MIT) was also obtained (mm).

Evaluation of Periarterial Small Vessels

Periarterial small vessels (PSV) were defined as echolucent luminal structures <1 mm in diameter observed by IVUS, located within 2 mm outside of the external elastic membrane (Figure 1). The signal void structures were excluded when they connected to the coronary lumen (considered as side branches) or could not be followed in ≥3 contiguous frames. The number of PSV was counted in each cross-section at 1-mm intervals throughout the first 50 mm of the LAD. The PSV score was calculated as the sum of cross-sectional values, and the change in PSV score (ΔPSV score) from baseline to 1 year was also calculated. Recipients with a significant increase in PSV, defined as ΔPSV score ≥4, were classified as the proliferative group. Calculations of PSV score in 10 randomly selected recipients by 2 observers, and by 1 observer at 2 separate sessions, showed an interobserver correlation coefficient of 0.972 and an intraobserver coefficient of 0.990.

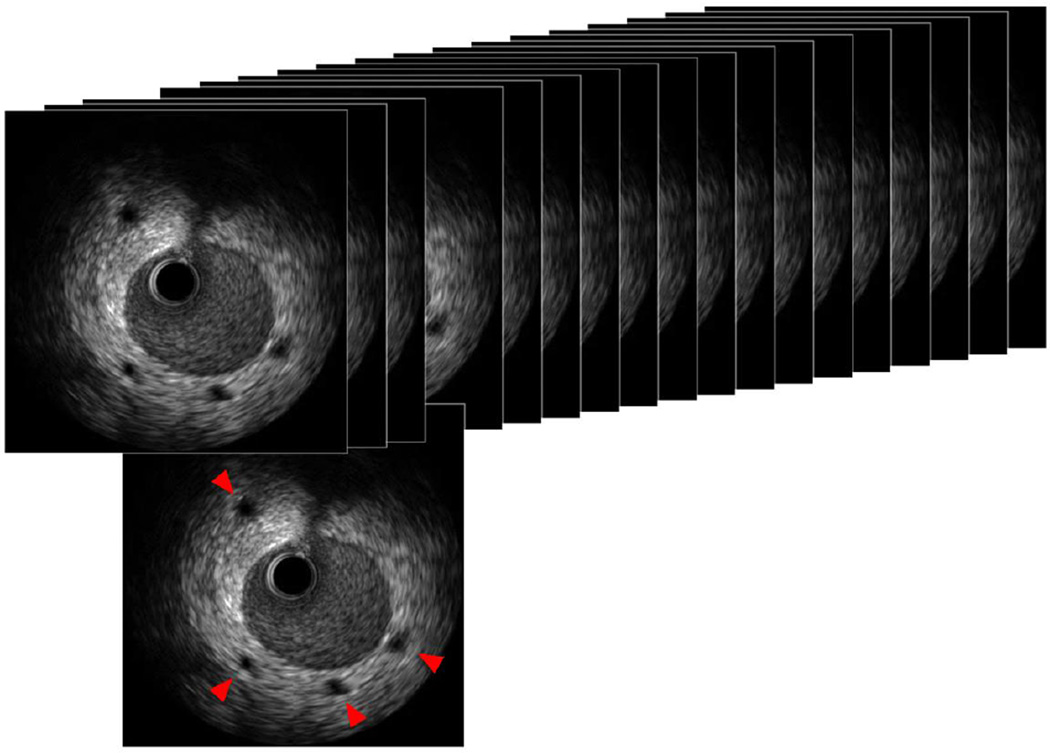

Figure 1. Periarterial small vessels.

Periarterial small vessels (PSV) were defined as echolucent luminal structures <1 mm in diameter, located within 2 mm of the external elastic membrane, and not connecting to the coronary artery lumen (red arrows). PSV score was calculated as the total number of PSV in the first 50 mm of the left anterior descending artery, counted at 1-mm intervals.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP® 10.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between 2 continuous variables were done with a 2-tailed, unpaired t-test. Serial changes in PSV score were evaluated with a paired t-test. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and compared using χ2 analyses. Survival analysis was performed by applying the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. A nominal p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Stratification by ΔPSV Score

The present study included 102 heart transplant recipients with serial IVUS images at baseline and 1 year after transplantation. One hundred and one out of 102 recipients (99%) had PSV at either baseline or 1 year. The mean PSV scores at baseline and 1 year were 15.8±11.0 and 16.3±10.4, respectively, and the distributions were similar, as shown in Figure 2. The mean ΔPSV score was 0.48±7.42 (p=0.515). Figure 3 displays a histogram of ΔPSV score from baseline to 1 year. The 75th percentile of ΔPSV score was 3.75 and, based on this value, recipients with ΔPSV score ≥4 were classified as the proliferative group. Clinical characteristics were comparable between the proliferative and the non-proliferative groups, except that donor age was significantly higher and the rate of pre-transplant ischemic cardiomyopathy tended to be higher in the non-proliferative group (Table 1).

Figure 2. PSV scores.

A: Histograms of PSV scores at baseline and 1 year. The mean PSV scores at baseline and 1 year were 15.8±11.0 and 16.3±10.4. B: The mean ΔPSV score from baseline to 1 year was 0.48±7.42.

Figure 3. Histogram of ΔPSV score from baseline to 1 year post-transplant.

The 75th percentile of ΔPSV score was 3.75. Based on this value, patients with ΔPSV score ≥4 were classified as the proliferative group.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Total (n=102) |

Proliferative (n=26) |

Non-Proliferative (n=76) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | ||||

| Age (years) | 47.8±16.4 | 47.7±14.0 | 47.8±17.2 | 0.960 |

| Male Gender (%) | 68.6 | 65.4 | 69.7 | 0.680 |

| Cold Ischemic Time (min) | 222.0±49.7 | 223.5±47.1 | 221.4±50.9 | 0.860 |

| Pre-transplantation ICM (%) | 27.2 | 12.5 | 33.3 | 0.054 |

| Hypertension (%) | 39.6 | 40.0 | 39.5 | 0.963 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 27.7 | 16.0 | 31.6 | 0.131 |

| Diabetes (%) | 14.9 | 16.0 | 14.5 | 0.852 |

| CMV IgG Positive (%) | 67.0 | 68.0 | 66.7 | 0.902 |

| ACE-I / ARB at 1 yr (%)* | 60.0 | 64.7 | 58.1 | 0.640 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker at 1 yr (%) |

69.7 | 64.0 | 71.6 | 0.473 |

| Statin at 1 yr (%) | 93.9 | 96.0 | 93.2 | 0.618 |

| Rapamycin at 1 yr (%) | 16.7 | 11.5 | 18.4 | 0.416 |

| Donor | ||||

| Age (years) | 30.3±13.0 | 34.8±13.9 | 28.8±12.4 | 0.045 |

| Male Gender (%) | 73.3 | 80.8 | 70.7 | 0.316 |

| CMV IgG Positive (%) | 68.0 | 62.5 | 69.9 | 0.502 |

ICM: ischemic cardiomyopathy; CMV: cytomegalovirus; ACE-I: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker.

Data were obtained in 60 patients.

Association between PSV proliferation and IVUS Parameters

In the overall study population, positive correlations were observed between ΔPSV score and IVUS parameters regarding intimal growth from baseline to 1 year post-transplant (Figure 4). In comparison between the proliferative and non-proliferative PSV groups, the proliferative group had larger vessel and intimal VI and MIT at baseline compared to the non-proliferative group (Table 2). At 1 year, the proliferative group had larger intimal VI, % intimal volume, and MIT compared to the non-proliferative group. From baseline to 1 year, a greater reduction of lumen VI, and a greater increase in intimal VI, % intimal volume, and MIT were observed in the proliferative group, compared with the non-proliferative group (Figure 5).

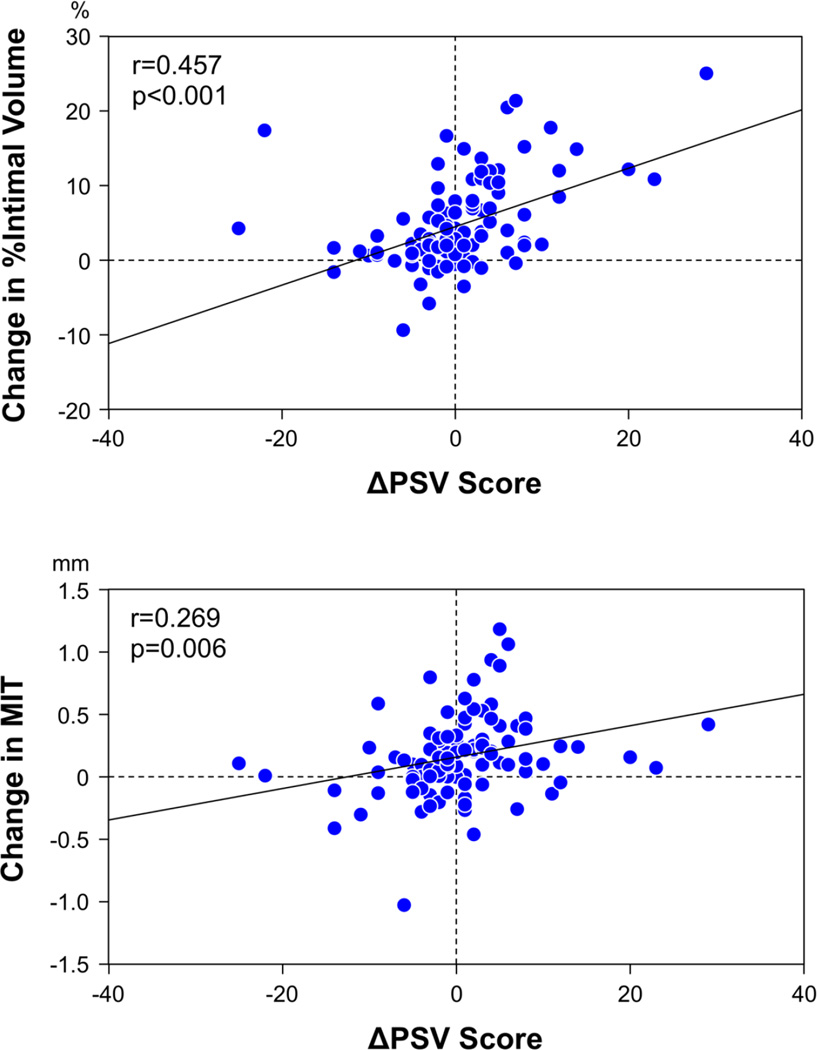

Figure 4. Correlations between ΔPSV score and IVUS parameters regarding intimal growth in overall population.

There were positive correlations between ΔPSV score and changes in % intimal volume and MIT from baseline to 1 year post-transplant. MIT = maximum intimal thickness.

Table 2.

Volumetric IVUS Analyses

| Proliferative (n=26) |

Non-Proliferative (n=76) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Lumen VI (mm3/mm) | 13.0±2.3 | 12.0±3.2 | 0.143 |

| Vessel VI (mm3/mm) | 16.3±2.7 | 14.5±3.8 | 0.032 |

| Intimal VI (mm3/mm) | 3.3±1.2 | 2.5±1.4 | 0.016 |

| % Intimal Volume (%) | 20.1±6.4 | 16.9±7.3 | 0.053 |

| Maximum Intimal Thickness (mm) | 1.09±0.52 | 0.70±0.44 | <0.001 |

| 1 Year Follow-up | |||

| Lumen VI (mm3/mm) | 10.3±2.2 | 10.8±3.1 | 0.473 |

| Vessel VI (mm3/mm) | 14.8±2.5 | 13.6±4.0 | 0.167 |

| Intimal VI (mm3/mm) | 4.4±1.5 | 2.8±1.5 | <0.001 |

| % Intimal Volume (%) | 30.1±9.2 | 20.2±8.2 | <0.001 |

| Maximum Intimal Thickness (mm) | 1.42±0.58 | 0.80±0.48 | <0.001 |

Figure 5. Comparison of change in IVUS parameters between the proliferative and non-proliferative groups.

From baseline to 1 year, a greater reduction of lumen VI, and greater increases in intimal VI, % intimal volume, and MIT were observed in the proliferative group, as compared to the non-proliferative group. MIT = maximum intimal thickness, VI = volume index.

Acute Cellular Rejection and Long-Term Clinical Outcomes

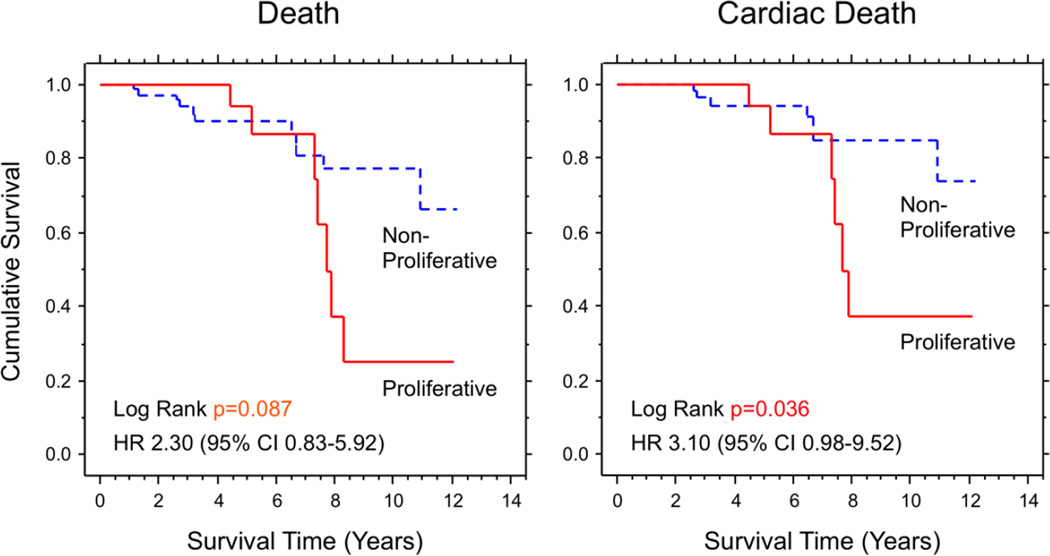

Significant acute cellular rejection during the first year post-transplant was observed in 29.8% of the overall population, and the incidence was significantly higher in the proliferative group than in the non-proliferative group (50.0% vs. 23.9%). Additionally, maximum severity of rejection was significantly higher in the proliferative group than in the non-proliferative group (1.45 vs. 1.10) (Figure 6), while the mean rejection score was not significantly different between the 2 groups (0.52 vs. 0.43, p=0.281). In the overall population, the incidences of all-cause mortality, cardiac death, and retransplantation after 1 year (median follow-up period was 4.7 years) were 17.6%, 12.7%, and 1.0%, respectively. Kaplan-Meier analyses for all-cause mortality and cardiac death are shown in Figure 7. Both overall survival and cardiac death-free survival were significantly lower in the proliferative group than the non-proliferative group. The best cut-off value of ΔPSV score for predicting cardiac death determined by ROC curve analysis was 3.5 (AUC: 0.627), which is comparable with the 75th percentile of ΔPSV score used to classify the recipients into the proliferative and non-proliferative groups.

Figure 6. Acute cellular rejection during the first year post-transplant.

The incidence of significant acute cellular rejection and maximum severity of rejection were significantly higher in the proliferative group than in the non-proliferative group. Significant acute cellular rejection was defined as one or more episode(s) of a grade ≥2R during the first year post-transplant, based on the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation 2004 revised grading scale. The degree of rejection was scored as 0R = 0, 1R = 1, 2R = 2, and 3R = 3, and maximum severity of rejection was determined as the highest score of any biopsy in each patient.

Figure 7. Kaplan-Meier analyses for all-cause death and cardiac death.

Overall survival tended to be lower, and cardiac death-free survival was significantly lower in the proliferative group compared to the non-proliferative group.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates the impact of proliferative changes in the small vessels around the coronary arteries on CAV progression and long-term clinical outcomes in heart transplant recipients. The main findings of this study are 1) the proliferative PSV group had greater progression of intimal thickening and a higher incidence of acute cellular rejection compared with the non-proliferative group; and 2) the incidence of cardiac death over a median period of 4.7 years was significantly higher in the proliferative group than in the non-proliferative group.

In Vivo Evaluation of the Vasa Vasorum

Neovascularization of the arterial wall, which is characterized by proliferation of the vasa vasorum, plays an important role in arterial inflammation and plaque progression in atherosclerotic lesions. (1,2) Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) is one of the established modalities for ex vivo assessment of the vasa vasorum, and the reported size of the vasa vasorum measured by micro-CT is usually 10–200 µm in diameter in experimental animal models. (12–16) However, due to unavailability of micro-CT for in vivo imaging, IVUS has been used to evaluate the vasa vasorum in the coronary arterial wall. Since the limited resolution of IVUS (150 to 200 µm) makes it difficult to directly visualize the small vasa vasorum as can be seen with micro-CT, several special imaging techniques using IVUS have been conducted and succeeded in detecting the vasa vasorum blood flow by contrast-enhanced IVUS, (3,4) or ChromaFlo® Imaging (Volcano Corporation, San Diego, CA; a specially developed IVUS system to visualize blood flow by detecting differences in the position of echogenic regions between temporally and spatially sequential images). (17) Recently, on the other hand, a histological study reported that the relatively large vasa vasorum in the adventitia could be visualized by conventional grey-scale IVUS. (5) Even though grey-scale IVUS is able to detect only relatively large vessels and unable to distinguish between arteries and veins, an increase in PSV detected by IVUS should represent vasa vasorum proliferation, because the number of blood vessels related to the vasa vasorum should increase, despite the vessel type, as the vasa vasorum proliferates.

Association of the Vasa Vasorum with CAV

Although the pathogenesis of CAV is distinct from native atherosclerosis, a previous study demonstrated a strong correlation between intragraft expression of angiogenic mediators, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, and intimal thickening in allograft coronary arteries. (7) In addition, the association of angiogenesis with intimal thickness in heart transplant recipients was also reported in previous histological studies. (8,18) On the other hand, there have been several in vivo OCT studies demonstrating the relationship between neovascularization and intimal thickness in CAV lesions. (9,19) However, those studies were based on single-time, cross-sectional evaluation. The present study is the first to provide temporal and serial assessment of neovascularization in heart transplant recipients, showing the contribution of proliferative change in PSV to intimal thickening and long-term adverse events. Some recipients had an increase in PSV, but others demonstrated a decrease from baseline to 1-year follow-up. It is unclear what factors contribute to this change in PSV score. Several types of drugs, such as statins, (16) endothelin receptor antagonists, (15) and Thalidomide (20) have been reported to prevent vasa vasorum neovascularization in experimental hypercholesterolemia. In this population, there were very few patients who did not receive statins, so that we could not determine whether statin therapy was associated with change in PSV score.

Acute Cellular Rejection and Long-Term Outcomes

In the current study, although the mean rejection score was not significantly associated with an increase in PSV score, both the incidence of significant rejection and maximum severity of rejection were significantly higher in the proliferative group than in the non-proliferative group. After heart transplantation, the transmural inflammation related to CAV often extends from the coronary artery intima to adventitia, and can even reach the perivascular tissues, (21,22) while inflammation is usually limited to the intima in atherosclerotic plaques. This widespread inflammation, which includes the tissue surrounding the blood vessels, may be associated with allograft rejection. Indeed, previous pathological reports have indicated that acute cellular rejection can affect cardiac structures beyond the myocardium and coronary arteries, such as the pericardium, after heart transplantation. (23–25) Furthermore, regardless of whether the type of rejection is cellular or antibody-mediated, acute rejection has a strong association with CAV progression. (26–28) Periarterial neovascularization and CAV progression, accompanied by inflammation of the blood vessels and surrounding tissues, may finally result in increased adverse events and lower survival rates. In this process, the proliferative change of PSV may represent one of the key predictive factors for CAV progression and long-term clinical outcomes in heart transplant recipients. Further prospective studies are warranted to explore the possible incremental value of this IVUS assessment over our current standard clinical care in the prediction of long-term outcomes after heart transplantation as well as in identification of high-risk patients who may benefit from closer follow-up and targeted medical therapies.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be noted in this IVUS study. First, the study population has an inherent selection bias toward healthier patients, since those recipients with a very complicated post-transplant course may not have follow-up IVUS imaging. Second, some other markers of a fibroproliferative phenotype or CAV progression, such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells or circulating endothelial progenitor cells, were not evaluated in the current study, which would be warranted in future investigations. Third, PSV detected by IVUS might include structures other than vasa vasorum (e.g. small veins). Fourth, vasa vasorum smaller than the resolution of IVUS (<150 µm) cannot be visualized. However, even though PSV includes some veins, and IVUS can visualize only relatively large vessels, increase in PSV may represent a part of vasa vasorum proliferation, as mentioned in the discussion. Last, PSV score measures the extent of PSV only in a semi-quantitative manner. The volume of small vessels or other more quantitative parameters should be further evaluated.

Conclusions

The increase in small vessels around the coronary arteries observed by IVUS, potentially representing an angioproliferative response, may be associated with early CAV progression and reduced long-term survival in heart transplant recipients.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Heidi N. Bonneau, RN, MS, CCA and M. Brooke Hollak, RN for their editorial review of the manuscript. This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health, Heart Lung and Blood Institute and the Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Bethesda, MD, grant 1 K23 HL072808-01A1 (W.F.F.).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CAV

cardiac allograft vasculopathy

- CT

computed tomography

- IVUS

intravascular ultrasound

- LAD

left anterior descending coronary artery

- MIT

maximum intimal thickness

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- PSV

periarterial small vessels

- VI

volume index

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Sirol M, Levy AP, Fuster V. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;113:2245–2252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle B, Caplice N. Plaque neovascularization and antiangiogenic therapy for atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2073–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Malley SM, Vavuranakis M, Naghavi M, Kakadiaris IA. Intravascular ultrasound-based imaging of vasa vasorum for the detection of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2005;8:343–351. doi: 10.1007/11566465_43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vavuranakis M, Kakadiaris IA, O'Malley SM, et al. A new method for assessment of plaque vulnerability based on vasa vasorum imaging, by using contrast-enhanced intravascular ultrasound and differential image analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kume T, Okura H, Fukuhara K, et al. Visualization of coronary plaque vasa vasorum by intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2013;6:985. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-first official adult heart transplant report–2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:996–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemstrom KB, Krebs R, Nykanen AI, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor enhances cardiac allograft arteriosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:2524–2530. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016821.76177.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson C, Southwood M, Pitman R, Phillpotts C, Wallwork J, Goddard M. Angiogenesis occurs within the intimal proliferation that characterizes transplant coronary artery vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aoki T, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Matsuo Y, et al. Evaluation of coronary adventitial vasa vasorum using 3D optical coherence tomography - Animal and human studies. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart S, Winters GL, Fishbein MC, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1710–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tu W, Potena L, Stepick-Biek P, et al. T-cell immunity to subclinical cytomegalovirus infection reduces cardiac allograft disease. Circulation. 2006;114:1608–1615. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon HM, Sangiorgi G, Ritman EL, et al. Enhanced coronary vasa vasorum neovascularization in experimental hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1551–1556. doi: 10.1172/JCI1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon HM, Sangiorgi G, Ritman EL, et al. Adventitial vasa vasorum in balloon-injured coronary arteries: visualization and quantitation by a microscopic three-dimensional computed tomography technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:2072–2079. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrmann J, Lerman LO, Rodriguez-Porcel M, et al. Coronary vasa vasorum neovascularization precedes epicardial endothelial dysfunction in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51:762–766. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrmann J, Best PJ, Ritman EL, Holmes DR, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Chronic endothelin receptor antagonism prevents coronary vasa vasorum neovascularization in experimental hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1555–7661. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SH, Herrmann J, Lerman LO, et al. Simvastatin preserves the structure of coronary adventitial vasa vasorum in experimental hypercholesterolemia independent of lipid lowering. Circulation. 2002;105:415–418. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.104119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moritz R, Eaker DR, Anderson JL, et al. IVUS detection of vasa vasorum blood flow distribution in coronary artery vessel wall. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2012;5:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seipelt IM, Pahl E, Seipelt RG, et al. Neointimal inflammation and adventitial angiogenesis correlate with severity of cardiac allograft vasculopathy in pediatric recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassar A, Matsuo Y, Herrmann J, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis with vulnerable plaque and complicated lesions in transplant recipients: new insight into cardiac allograft vasculopathy by optical coherence tomography. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2610–2617. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gossl M, Herrmann J, Tang H, et al. Prevention of vasa vasorum neovascularization attenuates early neointima formation in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:695–706. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu WH, Palatnik K, Fishbein GA, et al. Diverse morphologic manifestations of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a pathologic study of 64 allograft hearts. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angelini A, Castellani C, Fedrigo M, et al. Coronary cardiac allograft vasculopathy versus native atherosclerosis: difficulties in classification. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1586-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valantine HA, Hunt SA, Gibbons R, Billingham ME, Stinson EB, Popp RL. Increasing pericardial effusion in cardiac transplant recipients. Circulation. 1989;79:603–609. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seacord LM, Miller LW, Pennington DG, McBride LR, Kern MJ. Reversal of constrictive/restrictive physiology with treatment of allograft rejection. Am Heart J. 1990;120:455–459. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinkamp TJ, Sullivan HJ, Montoya A, Park S, Bartlett L, Pifarre R. Chronic cardiac rejection masking as constrictive pericarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:1579–1583. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caforio AL, Tona F, Fortina AB, et al. Immune and nonimmune predictors of cardiac allograft vasculopathy onset and severity: multivariate risk factor analysis and role of immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:962–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kfoury AG, Hammond ME, Snow GL, et al. Cardiovascular mortality among heart transplant recipients with asymptomatic antibody-mediated or stable mixed cellular and antibody-mediated rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:781–784. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu GW, Kobashigawa JA, Fishbein MC, et al. Asymptomatic antibody-mediated rejection after heart transplantation predicts poor outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]