Abstract

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease, whose etiology is still unclear. Its pathogenesis involves an interaction between genetic factors, immune response and the “forgotten organ”, Gut Microbiota. Several studies have been conducted to assess the role of antibiotics and probiotics as additional or alternative therapies for Ulcerative Colitis. Escherichia coli Nissle (EcN) is a nonpathogenic Gram-negative strain isolated in 1917 by Alfred Nissle and it is the active component of microbial drug Mutaflor® (Ardeypharm GmbH, Herdecke, Germany and EcN, Cadigroup, In Italy) used in many gastrointestinal disorder including diarrhea, uncomplicated diverticular disease and UC. It is the only probiotic recommended in ECCO guidelines as effective alternative to mesalazine in maintenance of remission in UC patients. In this review we propose an update on the role of EcN 1917 in maintenance of remission in UC patients, including data about efficacy and safety. Further studies may be helpful for this subject to further the full use of potential of EcN.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Escherichia coli Nissle, Metanalysis, Probiotic, Randomized trial, Inflammatory bowel disease

Core tip: Escherichia coli (E. coli) Nissle is a nonpathogenic Gram-negative strain used as a probiotic with very good quality paper assessing its bio-equivalence to mesalazine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Mechanisms of actions of this compound include immune-modulatory properties, reinforcement of intestinal barrier and inhibitory effect towards other pathogenic E. coli.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic remitting and relapsing disease, characterized by a continuous inflammation which can stretch from the rectum up to the entire colon, often resulting in mucosal ulceration, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, abdominal pain. Its etiology is still unclear, and it is multifactorial. Several factors have been identified as major determinants for induction or relapses and, among these, the imbalanced gut microbiota has become more crucial in recent years. The main hypothesis is that it is due to an excessive immune response to endogenous bacteria, in genetically predisposed individuals[1].

The human microflora, known as “microbiota”, includes more then thousand different species and higher than 15000 different bacterial strains, for an average total weight of 1 kg. In recent years several studies investigated the correlation between dysbiosis and intestinal and extra-intestinal diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and so UC[2].

Probiotics are viable agents conferring benefits to the health of the human host[3]. They can provide a beneficial effect on intestinal epithelial cells in numerous ways. Some strains can block pathogen entry into the epithelial cell by providing a physical barrier or by creating a mucus barrier; other probiotics maintain intestinal permeability acting on tight junctions. Some probiotic strains produce antimicrobial factors, other strains modulate the immune response[4].

The role of microbiota in UC was supported by several evidences: inflammation is greatest in intestinal tracts with high concentration of bacteria, surgical reduction of the bacterial load is associated with improvement of inflammation and inflammation does not occur in germ free animals[5].

The treatment goal of UC is the induction and the maintenance of remission. 5-aminosalicylic acid (ASA) compounds, azathioprine/6 mercaptopurine, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and anti-TNFα agents are conventional therapies used to control the disease. There are also other therapies, used as addition or alternative to conventional therapies in UC, in particular antibiotics and probiotics, which modulate gut microbiota.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) Nissle (EcN) 1917 is a nonpathogenic Gram-negative strain used in many gastrointestinal disorder including diarrhea[6], uncomplicated diverticular disease[7] and IBD, in particular UC[8].

STRUCTURE AND MECHANISMS OF ACTION OF EcN 1917

EcN 1917 (O6:K5:H1) was isolated by Prof. Alfred Nissle from Freiburg, Germany, in 1917 from the intestinal microflora of a young soldier. This soldier - unlike his comrades - did not develop infectious diarrhea, when stationed during World War I in Southeastern Europe (Dobrudja/Balkan peninsula), endemic for Shigella at that time. The strain was named E. coli strain Nissle 1917.

Using this E. coli strain Prof. Nissle developed the probiotic drug Mutaflor® and introduced it into medical practice in the same year. Since 1917, Mutaflor® is available in the German pharmaceutical market without interruption and recently also in Italy as EcN (cadigroup).

The lack of defined virulence factors (alpha-hemolysin, P-fimbrial adhesins, etc.) combined with the expression of fitness factors such as microcins, different iron uptake systems (enterobactin, yersiniabactin, aerobactin, salmochelin, ferric dicitrate transport system, and the chu heme transport locus), adhesins, and proteases may support its survival and efficacious colonization of the human gut, and contribute to the probiotic character of EcN 1917.

It exhibits a semi-rough lipopolysaccharide (LPS) phenotype and serum sensitivity and does not produce known toxins[9]. EcN colonizes the intestine within few days and it remains as colonic flora for months after administration[10].

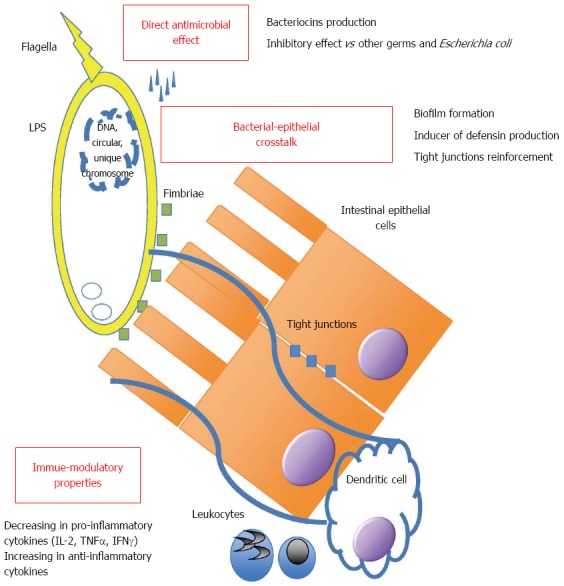

EcN has an intestinal anti-inflammatory effect, but also systemic effects[11], and there are many theories about its mechanism of action (Figure 1): (1) It has direct antimicrobial effects: it inhibits EHEC (E. coli EDL933) colonization in animal models[12] and synthesis of Shiga-Toxins in co-cultivation experiment with STEC (Shiga-Toxin producing E. coli)[13]. (2) It is involved in the bacterial-epithelial crosstalk (“Host cell signaling”) by biofilm formation: it expresses F1C Fimbria. This is very important in the formation of biofilm, adherence to epithelial cells and persistence in infant mouse colonization[14]. Its flagellum is the major “propulsor” in vivo, which allow this probiotic strain to efficiently compete with pathogens for binding sites on host tissue[15]. It directly stimulates defensin production by intestinal epithelial cells, such as the human beta-defensin that inhibits adhesion and invasion of intestinal cells by pathogenic adherent invasive E. coli, which play a key role as trigger in immune response in IBD patients[16-18]. It strengthens tight junctions of intestinal epithelial cells, by up-regulating the expression of the mRNA for the zonula occludens proteins ZO-1 and ZO-2, so it has an effect on the repair of the “leaky gut”[19-21]. (3) It interacts with immune system by causing decreasing in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-2, TNF-α, IFNγ) and increasing in anti-inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. It may reduce the expansion of newly recruited T cells into the intestinal mucosa and decrease intestinal inflammation, but it doesn’t affect activated tissue-bound T cells, which may eliminate deleterious antigens in order to maintain immunological homeostasis[22,23]. Furthermore EcN has a specific LPS that is responsible for its immunogenicity, without major immunotoxic properties at doses suggested and that provide, together with the other described features, a powerful effect on intestinal immune function[24].

Figure 1.

Structure and mechanisms of action of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; IL-2: Interleukin-2; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IFN: Interferon.

Efficacy of EcN in animal models of colitis

Schultz et al[25] conducted a study on animal models of acute and chronic colitis. Acute colitis was induced by administration of dextran-sodium sulfate (DSS) in drinking water and chronic colitis was induced by transferin CD4+ CD62L+ T lymphocytes from BALB/c mice in SCID mice. These studies have shown that administration of EcN ameliorates intestinal inflammation (measured by histological scores) in chronic models but not in acute models, in accordance with clinical observations. Therefore, it was shown that EcN reduced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, measured by enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay[25].

Grabig et al[5] demonstrated that EcN ameliorates experimental colitis induced by administration of 5% DSS in mice via TLR-2 and TLR-4 dependent pathway.

Decreasing of symptom scores and differences in body mass loss were shown in animal models of DSS colitis in BALB/c mice treated with EcN in the study conducted by Kokesová et al[26].

CLINICAL ROLE OF EcN 1917 IN MAINTANANCE OF UC

There are three major double-blind RCTs (Table 1), which compare EcN to mesalazine in prevention of relapse in UC patients, all of them designed to demonstrate equivalence of two treatment according to Schuirmann’s two-one side test or “non inferiority trials”.

Table 1.

Main results from trials on Escherichia coli Nissle on ulcerative colitis

| Efficacy of EcN 1917 in maintanance of UC remission |

| Results from major randomized controlled clinical trials |

| EcN 200 mg/d is equivalent to Mesalazine 1000 mg/d in mantainance of UC remission[27] |

| EcN 400 mg/d is equivalent to to Mesalazine 2400 mg/d in maintanance of UC remission following an acute flare[28] |

| EcN 200 mg/d is equivalent to Mesalazine 1500 mg/d in mantainance of UC remission[10] |

| Results from minor studies |

| Rectal admistration of EcN 40 mL/d is effective in moderate distal active UC[30] |

| EcN 200 mg/d is equivalent to Mesalazine 1500 mg/d in maintanance of UC remission[6] |

EcN: Escherichia coli Nissle; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

The first trial was conducted by Kruis et al[27] in 1997. It was a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study conducted on 120 out-patients in Germany, Czech Republic and Austria. Patients had a confirmed diagnosis of ulcerative colitis in remission. In particular patients had to be in remission for a maximum of 12 mo, with clinical activity index (CAI) < 4, no endoscopic or histological signs of acute inflammation. Each patient had to have had at least 2 relapses prior inclusion.

Patients received 500 mg mesalazine t.d.s. and a placebo form of EcN preparation or 200 mg/d of a preparation containing EcN in a single dose (“Mutaflor”, Ardeypharm GmbH, Herdecke, Germany. 100 mg contains 25 × 109 viable E. coli bacteria) and a placebo form of mesalazine. The duration of the study was 12 wk. Study objectives included the assessment of the equivalence of the CAI under the two treatment modalities and the comparison of the relapse rates, relapse-free times and global assessment.

Study population was homogeneous into the two groups, with a prevalence in left sided colitis and small prevalence of active use of steroids (less then 25 % in both groups).

From the results of this study, no significant difference was observed between the two groups, although a low statistical power and a minor trend towards a slightly higher CAI in the EcN group. No serious adverse events reported for both groups.

The second trial was conducted by Rembacken et al[28] in 1999. This was a single-center, randomised, double-dummy study involving 116 patients, which were treated with mesalazine 800 tds (Asacol formulation) or EcN 2 cp per 2 times daily (“Mutaflor”, Ardeypharm GmbH, Herdecke, Germany. 100 mg contains 25 × 109 viable E. coli bacteria).

Inclusion criteria were: 18-80 years of age, clinical active (mild-moderate and severe) ulcerative colitis (“Leeds-Index”) defined by number of 4 or more liquid stools/day for the last 7 d, with or without blood, erythema on sigmoidoscopy and histological confirmation of active ulcerative colitis.

The study populations were comparable. In particular: the median clinical activity index on study entry was 11 in the mesalazine group and nine in the EcN group (up to 30% of patients had a severe disease). The median sigmoidoscopy score was four in both groups. All patients received rectal or oral steroids at different doses together with a 1-wk course of oral gentamicin. At baseline both groups had an high active usage of steroids, around for 50% of the cases; furthermore, 2% in mesalazine group and 18% in EcN. In both groups the proportion between proctitis, left sided and pancolitis was similar (1/3 per each condition). No significant differences between the 2 groups were found.

Active treatment, started at the enrolment, was hydrocortisone enema twice daily, prednisolone 30 mg a day in moderate colitis and prednisolone 60 mg a day in severe colitis (according to Truelov Witts criteria). Only people in remission at 12 wk were enrolled in the follow up part of the trial assessing maintenance of remission.

Starting from remission, patients were maintained on either mesalazine or E. coli but the doses were reduced respectively at 1.2 g per day for the mesalazine group and 2 capsules per day for the EcN group. The follow up was at 12 mo. 59 were randomised to mesalazine and 57 to EcN. Of them 75% and 68% reached remission. Of those in remission, 73% of patients in the mesalazine group and 67% in the EcN group, relapsed by 12 mo. In the mesalazine group, the mean duration of remission was 206 d (median 175) compared with 221 (median 185) in the group given E. coli, (P = 0.0174). The treatment with EcN was proved safe, acceptable, and clinically equivalent to mesalazine in maintaining remission after an acute relapse of ulcerative colitis. Finally, this study is characterized by a very high rate of relapse: this is however not un-expected as the study population comprehends moderate and also severe patients.

The third trial was conducted by Kruis et al[10] in 2004. This was a double-blind, double dummy study in which 327 patients affected by ulcerative colitis in remission phase were recruited. 162 patients received Mutaflor 200 mg/d and 165 received Mesalazine 500 mg three times daily for 12 mo. Inclusion criteria were: age between 18-70 years, diagnosis of UC in remission [CAI ≤ 4, endoscopic index (EI) ≤ 4, and no signs of acute inflammation on histological examination]. Furthermore, within inclusion criteria there was at least two acute attacks of UC prior to the study and duration of the current remission of no longer than 12 mo. Primary objective of the study was meant to compare the number of patients experiencing a relapse during the 12 mo observation time between the two treatment groups. Secondary aims included efficacy variables like physician’s and patient’s assessment of general well being and calculation of a quality of life index. Additionally, time to relapse, CAI, EI, and histological findings were also evaluated. In the EcN group 36.4% of patients relapsed compared to 33.9% in the mesalazine group and statistical tests showed equivalence of the two treatments. A subgroup analyses showed no difference in terms of duration and localization of disease or pre-trial treatment. No difference of quality of life was shown in the two groups.

Overall same results on tolerance were found: it was very good or good in the EcN group in 80.0% and in the mesalazine group in 86.0%. According to the physician’s assessment, the respective values were 85.1% and 90.3%. No unexpected drug reactions occurred during the study.

This is perhaps the best study based on the quality of data and also the large number of patients enrolled. Furthermore clinical outcomes were assessed by well-established endoscopic and histological activity indices, like in modern trials for more powerful drugs.

In addition to the above-described trials, there is a multicentric placebo-controlled study on 90 patients with moderate distal active UC conducted by Matthes et al[29] Patients in EcN groups received EcN 40, 20 or 10 mL (amount of bacteria 10E8/mL) enema once daily for at least 2 wk. A clinical DAI was recorded after 2, 4 and/or 8 wk.

The majority of patients also received concomitant medical treatment such as oral mesalazine. Remission rates and improvement of the histological score was showed particularly in the EcN 40 mL group, but further studies on largest population are required.

This study has shown that rectal administration of EcN is an effective treatment, with a dose dependent efficacy as shown in the Per Protocol analysis. Unfortunately the ITT analysis did not show significant results[29].

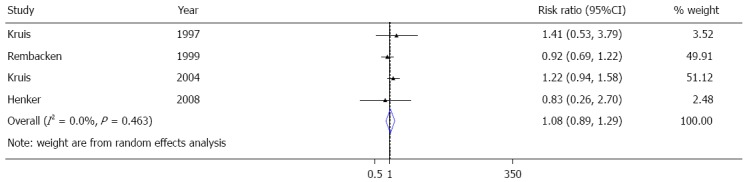

Many meta-analysis present in the literature support the role of ECN in the therapy of ulcerative colitis[6,10,27,28,30]. In particular, a very recent published meta-analysis, performed by Losurdo et al[31] (Figure 2), showed a non-significant inferiority of EcN in relapse prevention compared to mesalazine in preventing disease relapse, thus confirming current guideline recommendations[31], despite a novel randomized double-blinded placebo controlled trial conducted in Denmark and published very recently[32], with negative results. One hundred patients with active UC defined by CAI-score ≥ 6 and with calprotectin higher than 50 mg/kg, were enrolled and randomized into four groups of treatment: Ciprofloxacin (for 1 wk) followed by EcN (for 7 wk), Ciprofloxacin (for 7 wk) followed by placebo (for one week), placebo (for one week) followed by EcN (for 7 wk) and placebo (for one week) followed by placebo (for 7 wk). Aim of the study was the induction of the remission in ulcerative colitis and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare groups. In this study, the 54% of patients in the placebo/EcN group reached remission, compared to 89% of patients in the placebo/placebo group (P < 0.05), 78% of Ciprofloxacin/placebo group and 66% Ciprofloxacin/EcN group. Furthermore, the placebo/EcN group had the largest number of withdrawals. These impressive results, which would exclude a role of EcN in treatment of active ulcerative colitis, display several limitations, which make this study really weak. First of all this is a monocenter study, with a very not homogeneous population as showed in the table of patients characteristics. Mean CAI score at baseline was 10.5, 8.9, 9.3 and 8.9 in the Cipro/EcN, Cipro/placebo group, placebo/EcN group, placebo/placebo group, respectively. Furthermore patients clearly differed in concomitant medications use, in particular for use of active use of topical drugs and steroids as well as immunosuppressant. Taken together, these data suggest that this trial display major limitations regarding groups homogeneity. We confirmed the data from the published metanalysis, which we performed independently before discovering that it was just published. In the present paper we report an extract of the recent published metanalysis on the equivalence of the treatment between ECN and mesalazine[31], starting from the major trials available. An equivalence between EcN and mesalamine on maintenance of remission in UC is still detectable (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Metanalysis on randomized controlled trials assessing role of Escherichia coli Nissle on maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis.

Other studies assessing the use of EcN in ulcerative colitis

There is also an open-label multicenter pilot study that investigate the clinical benefit of EcN 1917 for maintenance therapy in young patients with UC. In this study 34 patients with UC in remission aged between 11 and 18 years were allocated either to EcN (2 capsules daily n = 24) or 5-ASA (median 1.5 g/d, n = 10), and observed over one year[33]. Inclusion criteria were: 11-18 years of age, ulcerative colitis in remission for a maximum of 12 mo, at least 2 relapses prior inclusion, active therapy with mesalazine. Taking into account the low statistical power of the study, relapse rate was 25% (6/24) in the EcN group and 30% (3/10) in the 5-ASA group. Data on the patients’ global health and development were favorable and no serious adverse events were reported[33].

CONCLUSION

EcN is a well known probiotic, used in several countries for GI diseases (Table 2)[6,10,27,28,34-41], registered as a drug in certain European countries, and it is the only one approved for maintenance of remission in UC patients by ECCO guidelines, based on data discussed also in the present paper. Trials designed to be non-inferiority/equivalence trials, comparing EcN to mesalazine, have reported equivalent rates of relapse between the two treatments, demonstrating that EcN is equivalent to mesalazine in the maintenance of remission in UC. Of the 3 major trials demonstrating these findings, the best and larger trial is the one conducted by Kruis et al and published on 2004. Finally, EcN showed a robust safe profile in UC patients. Further studies may be helpful to further dissect mechanisms of actions and perhaps optimize dose and newer indication of EcN.

Table 2.

Main potential clinical indications for Escherichia coli Nissle in gastroenterology

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Scaldaferri F and Gasbarrini A were consultants for Ca.Digroup; however, each author has no financial interests or connections, direct or indirect, or other situations that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or the conclusions.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 13, 2016

First decision: February 18, 2016

Article in press: May 4, 2016

P- Reviewer: Manguso F, Marie JC, Naito Y S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaldaferri F, Gerardi V, Lopetuso LR, Del Zompo F, Mangiola F, Boškoski I, Bruno G, Petito V, Laterza L, Cammarota G, et al. Gut microbial flora, prebiotics, and probiotics in IBD: their current usage and utility. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:435268. doi: 10.1155/2013/435268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reid G, Jass J, Sebulsky MT, McCormick JK. Potential uses of probiotics in clinical practice. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:658–672. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.658-672.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gareau MG, Sherman PM, Walker WA. Probiotics and the gut microbiota in intestinal health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:503–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grabig A, Paclik D, Guzy C, Dankof A, Baumgart DC, Erckenbrecht J, Raupach B, Sonnenborn U, Eckert J, Schumann RR, et al. Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 ameliorates experimental colitis via toll-like receptor 2- and toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathways. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4075–4082. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01449-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henker J, Laass MW, Blokhin BM, Maydannik VG, Bolbot YK, Elze M, Wolff C, Schreiner A, Schulze J. Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 versus placebo for treating diarrhea of greater than 4 days duration in infants and toddlers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:494–499. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318169034c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fric P, Zavoral M. The effect of non-pathogenic Escherichia coli in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:313–315. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000049998.68425.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz M. Clinical use of E. coli Nissle 1917 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1012–1018. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grozdanov L, Raasch C, Schulze J, Sonnenborn U, Gottschalk G, Hacker J, Dobrindt U. Analysis of the genome structure of the nonpathogenic probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5432–5441. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5432-5441.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J, Lukás M, Fixa B, Kascák M, Kamm MA, Weismueller J, Beglinger C, Stolte M, et al. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut. 2004;53:1617–1623. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arribas B, Rodríguez-Cabezas ME, Camuesco D, Comalada M, Bailón E, Utrilla P, Nieto A, Concha A, Zarzuelo A, Gálvez J. A probiotic strain of Escherichia coli, Nissle 1917, given orally exerts local and systemic anti-inflammatory effects in lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1024–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maltby R, Leatham-Jensen MP, Gibson T, Cohen PS, Conway T. Nutritional basis for colonization resistance by human commensal Escherichia coli strains HS and Nissle 1917 against E. coli O157: H7 in the mouse intestine. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reissbrodt R, Hammes WP, dal Bello F, Prager R, Fruth A, Hantke K, Rakin A, Starcic-Erjavec M, Williams PH. Inhibition of growth of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli by nonpathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;290:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lasaro MA, Salinger N, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhong Z, Goulian M, Zhu J. F1C fimbriae play an important role in biofilm formation and intestinal colonization by the Escherichia coli commensal strain Nissle 1917. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:246–251. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troge A, Scheppach W, Schroeder BO, Rund SA, Heuner K, Wehkamp J, Stange EF, Oelschlaeger TA. More than a marine propeller--the flagellum of the probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 is the major adhesin mediating binding to human mucus. Int J Med Microbiol. 2012;302:304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boudeau J, Glasser AL, Julien S, Colombel JF, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Inhibitory effect of probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 on adhesion to and invasion of intestinal epithelial cells by adherent-invasive E. coli strains isolated from patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:45–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Wehkamp K, Wehkamp-von Meissner B, Schlee M, Enders C, Sonnenborn U, Nuding S, Bengmark S, Fellermann K, et al. NF-kappaB- and AP-1-mediated induction of human beta defensin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917: a novel effect of a probiotic bacterium. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5750–5758. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5750-5758.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, Oelschlaeger TA, Stange EF, Fellermann K. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2399–2407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01563-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zyrek AA, Cichon C, Helms S, Enders C, Sonnenborn U, Schmidt MA. Molecular mechanisms underlying the probiotic effects of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 involve ZO-2 and PKCzeta redistribution resulting in tight junction and epithelial barrier repair. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:804–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otte JM, Podolsky DK. Functional modulation of enterocytes by gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G613–G626. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00341.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ukena SN, Singh A, Dringenberg U, Engelhardt R, Seidler U, Hansen W, Bleich A, Bruder D, Franzke A, Rogler G, et al. Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 inhibits leaky gut by enhancing mucosal integrity. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helwig U, Lammers KM, Rizzello F, Brigidi P, Rohleder V, Caramelli E, Gionchetti P, Schrezenmeir J, Foelsch UR, Schreiber S, et al. Lactobacilli, bifidobacteria and E. coli nissle induce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5978–5986. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i37.5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sturm A, Rilling K, Baumgart DC, Gargas K, Abou-Ghazalé T, Raupach B, Eckert J, Schumann RR, Enders C, Sonnenborn U, et al. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 distinctively modulates T-cell cycling and expansion via toll-like receptor 2 signaling. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1452–1465. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1452-1465.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grozdanov L, Zähringer U, Blum-Oehler G, Brade L, Henne A, Knirel YA, Schombel U, Schulze J, Sonnenborn U, Gottschalk G, et al. A single nucleotide exchange in the wzy gene is responsible for the semirough O6 lipopolysaccharide phenotype and serum sensitivity of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5912–5925. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.21.5912-5925.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz M, Strauch UG, Linde HJ, Watzl S, Obermeier F, Göttl C, Dunger N, Grunwald N, Schölmerich J, Rath HC. Preventive effects of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 on acute and chronic intestinal inflammation in two different murine models of colitis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:372–378. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.372-378.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kokesová A, Frolová L, Kverka M, Sokol D, Rossmann P, Bártová J, Tlaskalová-Hogenová H. Oral administration of probiotic bacteria (E. coli Nissle, E. coli O83, Lactobacillus casei) influences the severity of dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in BALB/c mice. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2006;51:478–484. doi: 10.1007/BF02931595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruis W, Schütz E, Fric P, Fixa B, Judmaier G, Stolte M. Double-blind comparison of an oral Escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:853–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:635–639. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthes H, Krummenerl T, Giensch M, Wolff C, Schulze J. Clinical trial: probiotic treatment of acute distal ulcerative colitis with rectally administered Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonkers D, Penders J, Masclee A, Pierik M. Probiotics in the management of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of intervention studies in adult patients. Drugs. 2012;72:803–823. doi: 10.2165/11632710-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Losurdo G, Iannone A, Contaldo A, Ierardi E, Di Leo A, Principi M. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in Ulcerative Colitis Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:499–505. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.244.ecn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen AM, Mirsepasi H, Halkjær SI, Mortensen EM, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Krogfelt KA. Ciprofloxacin and probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle add-on treatment in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1498–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henker J, Müller S, Laass MW, Schreiner A, Schulze J. Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) for successful remission maintenance of ulcerative colitis in children and adolescents: an open-label pilot study. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:874–875. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruis W, Chrubasik S, Boehm S, Stange C, Schulze J. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial to study therapeutic effects of probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in subgroups of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:467–474. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1363-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Różańska D, Regulska-Ilow B, Choroszy-Król I, Ilow R. [The role of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 in the gastro-intestinal diseases] Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2014;68:1251–1256. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1127882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plassmann D, Schulte-Witte H. [Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 (EcN): a retrospective survey] Med Klin (Munich) 2007;102:888–892. doi: 10.1007/s00063-007-1116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krammer HJ, Kämper H, von Bünau R, Zieseniss E, Stange C, Schlieger F, Clever I, Schulze J. [Probiotic drug therapy with E. coli strain Nissle 1917 (EcN): results of a prospective study of the records of 3,807 patients] Z Gastroenterol. 2006;44:651–656. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-926909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behnsen J, Deriu E, Sassone-Corsi M, Raffatellu M. Probiotics: properties, examples, and specific applications. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a010074. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Möllenbrink M, Bruckschen E. [Treatment of chronic constipation with physiologic Escherichia coli bacteria. Results of a clinical study of the effectiveness and tolerance of microbiological therapy with the E. coli Nissle 1917 strain (Mutaflor)] Med Klin (Munich) 1994;89:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henker J, Laass M, Blokhin BM, Bolbot YK, Maydannik VG, Elze M, Wolff C, Schulze J. The probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 (EcN) stops acute diarrhoea in infants and toddlers. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:311–318. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0419-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tromm A, Niewerth U, Khoury M, Baestlein E, Wilhelms G, Schulze J, Stolte M. The probiotic E. coli strain Nissle 1917 for the treatment of collagenous colitis: first results of an open-label trial. Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:365–369. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-812709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]