Abstract

A 35-year-old man of average build and a smoker, with a background of a psychiatric disorder, was brought by his neighbor to the emergency department after an hour of severe chest pain. Upon arrival at the hospital he had cardiac arrest, was resuscitated, and moved to the catheterization laboratory with inferior, posterior, and lateral myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography showed an unusual thrombosis in multiple coronary branches. Toxicology report showed high levels of amphetamines and benzodiazepines in the patient’s original blood sample. The patient was kept under ventilation for 18 days, with difficult recovery due to severe withdrawal manifestations, ventilation acquired pneumonia, and rhabdomyolysis inducing acute renal failure. The patient regained near normal left ventricular function after baseline severe regional and global dysfunction. We postulate a relationship between the use of amphetamines, potentiated by benzodiazepines, and occurrence of acute thrombosis of multiple major coronary arteries.

Keywords: Amphetamines, Benzodiazepine, Coronary, Myocardial infarction, Thrombosis

Introduction

Amphetamines are common for drug abuse, especially in the young population, where mixed drug abuse is not uncommon [1]. Amphetamines increase the blood pressure, heart rate, and platelet aggregation [2], and induce tissue factor expression, inducing thrombosis [3]; they might also accelerate atherosclerosis and trigger plaque rupture [4]. Benzodiazepines synergistically potentiate myocardial ischemia mediated through the positive inotropic effects of catecholamines [5].

Case report

A 35-year-old man of average build was brought to the emergency department by his neighbor with severe chest pain for an hour. The patient is an active smoker and under follow-up for a psychiatric disease for several years. Emergency triage revealed blood pressure of 115/65 mmHg and a heart rate of 105 beats/min. A few minutes later the patient developed ventricular fibrillation, and resuscitation was done for 15 minutes. The electrocardiogram showed ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the inferior, posterior, and lateral leads (Fig. 1). The patient was intubated and given 5000 IU of heparin. Aspirin 300 mg and clopidogrel 600 mg were given via a nasogastric tube and he was moved to the catheterization laboratory. Coronary angiography showed a dominant, normal caliber, normal flow right coronary artery (RCA), with a thrombus in its proximal segment (Fig. 2). The left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was normal (Fig. 3). The first obtuse marginal branch (OM1) of the left circumflex (LCX) had a hazy ostial lesion, and the second obtuse marginal branch (OM2) was totally occluded (Fig. 3A). The OM2 was successfully opened and optimally stented using a 3.0 mm × 16 mm bare metal stent. Angiography showed reappearing thrombi in the LCX, even after repeated thrombus aspiration, and a total of 10,000 IU of heparin as well as abciximab given as a bolus and continuous infusion during the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedure (Fig. 4). The procedure was stopped at this stage and the patient was moved to the coronary care unit. Transthoracic echocardiography showed globally impaired contractility with akinetic inferior and lateral walls, with left ventricular ejection fraction of 20–25%. The patient needed inotropic agents for 24 hours. The first blood sample taken upon patient arrival at the hospital showed drug abuse with amphetamines and benzodiazepines. History taking from the wife and family, as well as the routine laboratory tests, revealed no additional cardiovascular risk factors. Serial electrocardiogram and laboratory tests showed gradual recovery from the myocardial infarction (MI); however, the patient was kept under ventilation, with use of olanzapine and diazepam to control his withdrawal symptoms under the care of intensive care and psychiatric consultations. Follow-up transthoracic echocardiography showed improvement of the global and regional contractility with left ventricular ejection fraction of 45%. The patient developed ventilation acquired pneumonia with fever and rigors that improved gradually; he also developed rhabdomyolysis with acute renal shutdown and was kept under hemodialysis. He was gradually weaned from ventilation and extubated after 18 days; his kidneys recovered totally. A future plan and multidisciplinary team follow-up was set before discharging the patient home.

Figure 1.

Initial electrocardiogram at presentation showing sinus tachycardia with ST-segment elevation in (A) leads II, III, AvF, and V4-V6, with ST-segment depression in V1–V3 and (B) posterior leads ST-segment elevation.

Figure 2.

The right coronary angiogram in (A) left anterior oblique projection and (B) left anterior oblique with cranial angulations, both showing patent artery with thrombus (arrows). The insets are zoomed views.

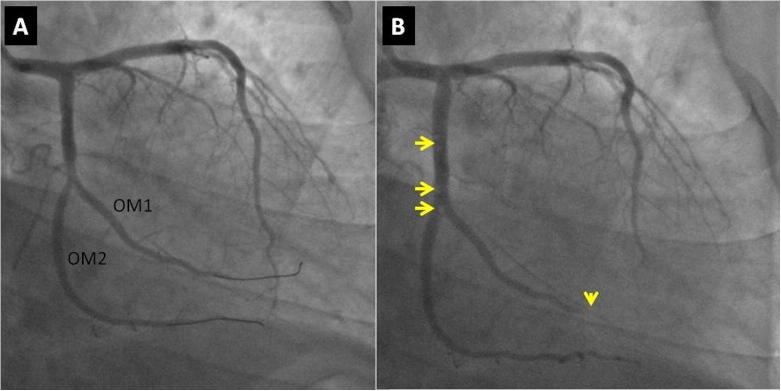

Figure 3.

Left coronary angiogram in the right anterior oblique projection shows (A) hazy ostial lesion at the first obtuse marginal branch (arrow), with (B) totally occluded the second obtuse marginal branch and normal left anterior descending artery also confirmed by cranial angulations.

Figure 4.

The obtuse marginal (OM) branches (A) after recanalization with balloon and (B) the final result with multiple thrombi in the left circumflex artery (arrows) and distal embolization to the first obtuse marginal branch (arrowhead).

Discussion

This case provides a unique presentation and management course. The most important factor was the multiple coronary thromboses despite aggressive anticoagulation therapy in a young, relatively low-risk patient, on two abused drugs with synergistically harmful effects. The case also demonstrates the need for unusually prolonged ventilation and psychotropic medications, with multidisciplinary management, to control the difficult course of drug withdrawal manifestations.

Amphetamines are potent sympathomimetic agents that block presynaptic reuptake of catecholamines, leading to enhanced sympathetic stimulation, with primarily a rise in pulse and blood pressure [2]. Amphetamines induce endothelial tissue factor expression, a key trigger of thrombosis, and impair tissue factor pathway inhibitor. They also increase expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, a key fibrinolysis suppressant in human vascular endothelial cells; these mechanisms might account for the increased incidence of acute vascular syndromes after amphetamine consumption [3]. Moreover, amphetamines are known to increase platelet aggregation and trigger atherosclerotic plaque rupture [2], [4]. The cardiovascular effects of amphetamines include a strong association with MI [3], [6], probably related to catecholamine surge, coronary vasospasm, and coronary thrombosis [7]. Additionally, the chronic use of amphetamines is described to promote coronary atherosclerosis [4], [7]; however, cases in the literature classically describe coronary vasospasm [8], [9]. Benzodiazepines probably exert dual intoxication with amphetamines; diazepam exerts an inhibitory activity on different isoforms of the enzyme cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase, by which they potentiate the effect of both noradrenaline and adrenaline on cardiac tissue and coronary arteries which results in larger myocardial injury [5].

Acute MI with documented amphetamines and benzodiazepines abuse is rarely described in the literature. We believe that the association between amphetamine–benzodiazepine abuse and MI in our patient is unlikely to be just simply coincidental. The patient’s original severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and generalized wall motion abnormality might be due to MI and cardiac arrest; however, amphetamine is reported to induce acute cardiomyopathy [10]. A review of acute MI associated with amphetamine use included 10 reported cases with evident coronary lesions in only two cases of them, both in the LAD [9]. Therefore, the presence of multiple coronary arterial thromboses in our case is unusual in the literature. Moreover, diagnosis of STEMI among amphetamine users with simultaneous thrombosis of the LCX and the RCA has not been reported previously. By contrast, cases with abnormalities in the LAD artery [9], [11], RCA [6], [11], or LCX alone [12] due to amphetamine use have been reported. Also interesting in our case is the persistent thrombosis despite aggressive anticoagulation.

Simultaneous coronary artery thrombosis in the setting of STEMI is very rare, and is usually associated with cardiogenic shock and life-threatening arrhythmia [13]. There are a few reports of acute MI with multiple acute coronary obstructions associated with drug addiction, that either was treated medically [11], treated successfully with PCI [14], or died after PCI [15]. Our case is probably the first report of successful management of a multivessel acute coronary thrombosis in a patient with amphetamine–benzodiazepine addiction. Importantly, prolonged sedation under ventilation in our case helped controlling the drug abuse withdrawal period.

Conclusion

This case of amphetamine plus benzodiazepine-induced STEMI, with multiple coronary thromboses, is a good example for understanding the range of possible drug-induced cardiovascular manifestations and how to manage a difficult withdrawal recovery, and to keep hope using patient multidisciplinary team management.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment is owed to all doctors in the cardiology, nephrology, psychiatry and intensive care for their help treating the patient.

Disclosures: Author has nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- 1.Richards J.R., Bretz S.W., Johnson E.B., Turnipseed S.D., Brofeldt B.T., Derlet R.W. Methamphetamine abuse and emergency department utilization. West J Med. 1999;170:198–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertson T.E., Derlet R.W., Van Hoozen B.E. Methamphetamine and the expanding complications of amphetamines. West J Med. 1999;170:214–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebhard C., Breitenstein A., Akhmedov A., Gebhard C.E., Camici G.G., Lüscher T.F. Amphetamines induce tissue factor and impair tissue factor pathway inhibitor: role of dopamine receptor type 4. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1780–1791. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westover A.N., Nakonezny P.A., Haley R.W. Acute myocardial infarction in young adults who abuse amphetamines. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starcevic B., Sicaja M. Dual intoxication with diazepam and amphetamine: this drug interaction probably potentiates myocardial ischemia. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:377–380. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furst S.R., Fallon S.P., Reznik G.N., Shah P.K. Myocardial infarction after inhalation of methamphetamine. New Engl J Med. 1990;323:1147–1148. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010183231617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashour T.T. Acute myocardial infarction resulting from amphetamine abuse: a spasm-thrombus interplay? Am Heart J. 1994;128:1237–1239. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J.P. Methamphetamine-associated acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock with normal coronary arteries: refractory global coronary microvascular spasm. J Invasive Cardiol. 2007;19:E89–E92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waksman J., Taylor R.N., Jr, Bodor G.S., Daly F.F., Jolliff H.A., Dart R.C. Acute myocardial infarction associated with amphetamine use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:323–626. doi: 10.4065/76.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Call T.D., Hartneck J., Dickinson W.A., Hartman C.W., Bartel A.G. Acute cardiomyopathy secondary to intravenous amphetamine abuse. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:559–560. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-4-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaheshi I., Mahjoob M.P., Esmaeeli S., Eslami V., Haybar H. Simultaneous thrombosis of the left anterior descending artery and the right coronary artery in a 34-year-old crystal methamphetamine abuser. Korean Circ J. 2015;45:158–160. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2015.45.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khattab E., Shujaa A. Amphetamine abuse and acute thrombosis of left circumflex coronary artery. Int J Case Rep Images. 2013;4:698–701. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Suwaidi J., Al-Qahtani A. Multiple coronary artery thrombosis in a 41-year-old male patient presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;24:E43–E46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meltser H., Bhakta D., Kalaria V. Multivessel coronary thrombosis secondary to cocaine use successfully treated with multivessel primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent. 2004;6:39–42. doi: 10.1080/14628840310016871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan W.R., Yeh H.I., Hou C.J.Y., Chou Y.S. Acute thrombosis of double major coronary arteries associated with amphetamine abuse. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2007;23:268–272. [Google Scholar]