Abstract

Aims

SB4 has been developed as a biosimilar of etanercept. The primary objective of the present study was to demonstrate the pharmacokinetic (PK) equivalence between SB4 and European Union ‐sourced etanercept (EU‐ETN), SB4 and United States‐sourced etanercept (US‐ETN), and EU‐ETN and US‐ETN. The safety and immunogenicity were also compared between the treatments.

Methods

This was a single‐blind, three‐part, crossover study in 138 healthy male subjects. In each part, 46 subjects were randomized at a 1:1 ratio to receive a single 50 mg subcutaneous dose of the treatments (part A: SB4 or EU‐ETN; part B: SB4 or US‐ETN; and part C: EU‐ETN or US‐ETN) in period 1, followed by the crossover treatment in period 2 according to their assigned sequences. PK equivalence between the treatments was determined using the standard equivalence margin of 80–125%.

Results

The geometric least squares means ratios of AUCinf, AUClast and Cmax were 99.04%, 98.62% and 103.71% (part A: SB4 vs. EU‐ETN); 101.09%, 100.96% and 104.36% (part B: SB4 vs. US‐ETN); and 100.51%, 101.27% and 103.29% (part C: EU‐ETN vs. US‐ETN), respectively, and the corresponding 90% confidence intervals were completely contained within the limits of 80–125 %. The incidence of treatment‐emergent adverse events was comparable, and the incidence of the antidrug antibodies was lower in SB4 compared with the reference products.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated PK equivalence between SB4 and EU‐ETN, SB4 and US‐ETN, and EU‐ETN and US‐ETN in healthy male subjects. SB4 was well tolerated, with a lower immunogenicity profile and similar safety profile compared with those of the reference products.

Keywords: biosimilar, etanercept, immunogenicity, pharmacokinetics, safety, SB4

What is Already Known about this Subject

A biosimilar is a biological medicine that is highly similar to another biological medicine that has already been authorized for use.

Etanercept (Enbrel®) is a biological product originally approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, and biosimilar products to etanercept are in development by several pharmaceutical companies.

A comparative PK study is an essential part of, and the first step to, a biosimilar clinical development programme.

What this Study Adds

SB4 has been developed as a biosimilar to etanercept by Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd.

SB4 was shown to be equivalent to the reference products (EU‐sourced etanercept and US‐sourced etanercept), in terms of PK after single‐dose administration in healthy subjects.

SB4 was well tolerated, with a lower immunogenicity profile and similar safety profile compared with those of the reference products.

Introduction

Etanercept (ETN; Enbrel®, Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) is a recombinant human tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR) p75Fc fusion protein 1. It has been widely used in clinical practice for approximately 15 years, with a well characterized pharmacological, efficacy and safety profile 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Originally licensed for use in moderate‐to‐severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the therapeutic indications have been extended stepwise and now comprise the treatment of patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis and paediatric psoriasis. Recently, ETN has also been approved for use in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) 8.

A biosimilar is a biological medicinal product that is highly similar to an already authorized original biological medicinal product (reference medicinal product) in terms of quality, safety and efficacy, based on a comprehensive comparability exercise 9, 10, 11. According to biosimilar guidelines from the EMA and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), nonclinical studies to evaluate the structural characteristics, physicochemical properties, in vitro biological activities and in vivo behaviour are required before initiating clinical studies to compare the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics (PK) of the biosimilar with those of the reference product, to demonstrate biosimilarity 9, 11.

SB4 has been developed as a biosimilar to ETN by Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd, Incheon, Republic of Korea. An extensive characterization of structural, physiochemical and biological attributes of SB4 and ETN was conducted using 61 analytical methods. The similarity of quality between SB4 and ETN was evaluated based on the similarity range (mean ± kSD) that had been set with ETN or a head‐to‐head comparison of analytical data. The characterization studies included an extensive comparison of primary, secondary and tertiary structure, purity and process‐related impurities; glycan content and identity; and biological activities based on the mechanism of action. These extensive characterization studies showed that SB4 has an identical primary amino acid sequence to ETN. In addition, SB4 and ETN showed similar binding activities to TNF (TNF‐α and lymphotoxin α3) and similar potency, assessed by the TNF‐α neutralization assay using the nuclear factor‐κB reporter gene. On the other hand, the proportion of high molecular weight and misfolded species was lower in SB4 than in ETN; however, these species are believed to be inactive, and being usually in the form of aggregates, potentially cause unfavorable effects. In the case of the N‐/O‐glycosylation site, three N‐glycosylation and 13 potential O‐glycosylation sites of SB4 were identical to those of ETN, and these identical glycosylation sites rendered total sialic acid content highly similar to that of ETN. Some minor differences in the relative content of N‐glycan species and charge heterogeneity were detected in SB4 compared with ETN but they were not considered as significant for the biological function of ETN based on the demonstration of comparable TNF‐α binding activity and TNF‐α neutralization activity to ETN (Cho et al., manuscript submitted) 12. In addition, nonclinical studies, including a pharmacodynamic comparison study in collagen antibody‐induced arthritic mice and a four‐week repeated toxicity study in cynomolgus monkeys, showed that SB4 and ETN had similar behaviour in vivo 12.

Based on quality and nonclinical studies, clinical studies were conducted to demonstrate PK and therapeutic equivalence between SB4 and ETN. SB4 has been recently granted marketing authorization in the European Union (EU) under the trade name Benepali® and in the Republic of Korea under the trade name Brenzys®. The present article provides the results of the first clinical study of SB4 designed to demonstrate the PK equivalence of SB4 and its reference products in healthy male subjects.

Methods

Study design

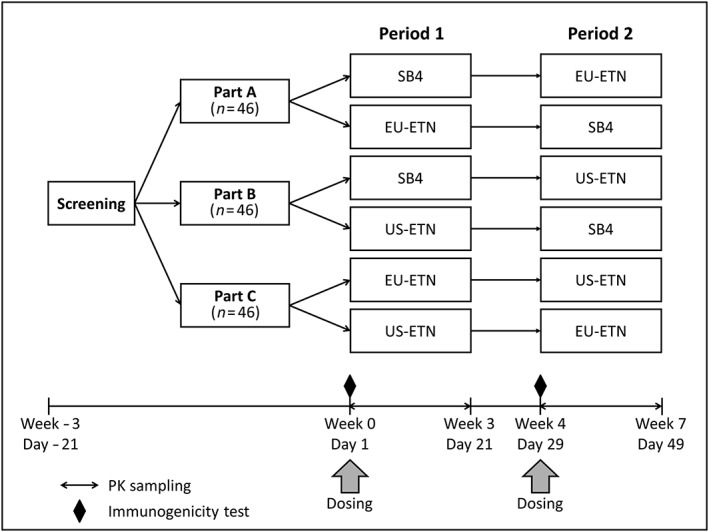

The study comprised three parts (parts A, B and C), in which each part had a randomized, single‐blind, two‐period, two‐sequence, single‐dose, crossover study design (Figure 1). There was a 28‐day washout period between drug administration in periods 1 and 2. The primary objective of the present study was to demonstrate PK equivalence between SB4 and EU‐ETN (part A), between SB4 and US‐ETN (part B) and between EU‐ETN and US‐ETN (part C). The secondary objectives were to compare safety, tolerability and immunogenicity between the two treatments in each part.

Figure 1.

Three‐part, two‐period, two‐sequence, single‐dose, crossover study design. In each of parts A, B and C, 46 healthy male subjects were randomized 1:1 to receive a single 50 mg subcutaneous dose of the treatments [part A: SB4 or EU‐ETN; part B: SB4 or US‐ETN; part C: EU‐ETN or US‐ETN) in period 1, followed by the crossover treatment in period 2, according to their assigned sequences. The study treatments were separated by a 28‐day washout period. PK, pharmacokinetic

The subjects had to be between the ages of 18 and 55 years and to have a body mass index (BMI) between 20.0 and 29.9 kg m–2. Subjects were required to have normal screening results for vital signs, physical examinations, clinical laboratory tests and 12‐lead electrocardiograms (ECGs). Subjects with a history and/or current presence of clinically significant atopic allergies, hypersensitivity or allergic reactions to ETN, or with either active or latent tuberculosis (TB) [assessed using the QuantiFERON®‐TB Gold test (QIAGEN, Venlo, the Netherlands)] and/or a history of TB, and those with any other clinically significant disease were excluded from the study. Subjects with a previous exposure to ETN were also excluded.

Subjects who met all of the inclusion/exclusion criteria were hospitalized in the PAREXEL Early Phase Clinical Unit (Berlin, Germany) on the day before the drug was administered in period 1 and received one of investigational drugs subcutaneously in the periumbilical area, according to their sequence. The subjects were discharged on the sixth day after drug administration and required to visit the Clinical Unit subsequently to assess the PK, safety and immunogenicity up to 21 days after drug administration. During the second period, subjects received the other drug, according to their sequence. The schedule of the activities was the same as in period 1.

A sample size of 32 completing subjects in each part of the study would provide at least 90% power to detect a 20% difference in PK between the test and reference drug. This assumed an intrasubject coefficient of variation (CV) of 25% based upon previously generated PK data 13. Thus, to allow for the possibility of all randomized subjects not completing the whole study period, a sample size of 38 subjects was chosen, to ensure that we could measure PK parameters for at least 32 subjects, for both periods.

The study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol and its amendments were approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Berlin. All of the participants provided written informed consent prior to any study‐related procedures. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01865552).

Pharmacokinetic evaluations

Blood samples for PK analysis were collected predose and at 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, 120, 144, 168, 216, 312 and 480 h after each treatment. The serum concentration was measured by a validated enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay that detects SB4 and reference products in the serum using mouse monoclonal human TNFRII/TNFRSF1B antibody and goat polyclonal human TNFRII/TNFRSF1B biotinylated antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The lower limit of quantification of the assay was 0.02 μg ml–1. The interbatch assay accuracy was expressed as the percentage relative error for a quality control sample (%) and ranged from −12.4% to 11.1%. The interbatch assay precision was expressed as the relative standard deviation (%) and ranged from 6.7% to 19.8%.

The concentration–time data were analysed with a noncompartmental method, using WinNonlin® 6.2 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA). The maximum concentration (C max) and time to C max (T max) were obtained directly from the observed values. The terminal elimination rate constant (λz) was estimated in the terminal phase by linear regression after loge‐transformation of the concentrations. The terminal half‐life was calculated as ln(2)/λz. The linear up/log down trapezoidal rule was used to obtain the area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to the last quantifiable concentration (AUClast). AUC extrapolated to infinity (AUCinf) was calculated as AUClast + C last/λz, where C last is the last quantifiable concentration. Apparent clearance (CL/F) was calculated as the dose/AUCinf, and the apparent volume of distribution (Vz/F) was estimated as CL/F/λz.

The statistical analysis of the loge‐transformed primary PK parameters (AUCinf, AUClast and C max) was conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with SAS 9.2 (Statistical Analysis System, SAS‐Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Sequence, subject, period and treatment were included in the ANOVA model as fixed effects and the subject effect nested within the sequence was tested as a random effect. The differences in least squares means (LSMeans) of the loge‐transformed primary PK parameters between SB4 and EU‐ETN, SB4 and US‐ETN, and EU‐ETN and US‐ETN, and the corresponding 90% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined. Back transformation provided the ratio of geometric means and the related 90% CIs for the original parameters. PK equivalence was demonstrated if the 90% CI for the ratio of geometric LSMeans of the pairwise comparison was within the predefined equivalence margin of 80–125% 14, 15.

Safety evaluations

All adverse events (AEs) recorded during the course of the study were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (Version 15.1). The safety assessments included clinical laboratory tests, 12‐lead ECGs, vital signs and physical examinations.

Immunogenicity evaluations

Blood samples for detecting antidrug antibodies (ADA) and the neutralizing antibodies (NAb) were collected only at predose in period 1 (day 1, baseline) and predose in period 2 (day 29) to investigate the development of ADA against the first treatment administered in period 1. As it may have been difficult to identify which product caused an ADA detected after period 2, no additional blood samples were collected during the study. The samples were analysed by Covance Laboratories Ltd (Harrogate, UK).

The samples for immunogenicity evaluation were analysed following an approach using validated tiered electrochemiluminescent (ECL) immunoassays; these involved an initial screen, in which samples were assessed for the presence of ADA, followed by a confirmation assay, which determined whether a positive sample in screening reacted specifically with the free drug. The ECL method is a bridging ligand binding assay, using labelled versions of SB4, to minimize bioanalytical bias associated with interassay variability and the possibility of inconsistent false‐positive/false‐negative results due to the labelling of multiple antigens (to minimize preparing biotinylated and ruthenylated forms of both SB4 and ETN) and to detect ADAs to the neo‐epitope of SB4.

A validated cell‐based assay was used to determine whether ADA‐positive samples had a neutralizing activity.

Results

Subject disposition

A total of 138 male subjects were enrolled in the study. The average age, height, weight and BMI of the subjects were similar across the three parts of the study. The majority of the subjects were white (Table 1). The demographics were also comparable between the sequences in each part (Table S1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects (mean ± SD)

| Part A | Part B | Part C | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 46 | 46 | 46 | 138 |

| Age (years) | 39 ± 10.2 | 40 ± 9.5 | 41 ± 9.9 | 40 ± 9.8 |

| Race (n) | ||||

| White | 46 | 45 | 44 | 135 |

| Black or African American | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Height (cm) | 181 ± 6 | 178 ± 7 | 179 ± 7 | 179 ± 7 |

| Weight (kg) | 79.5 ± 8.5 | 77.8 ± 7.3 | 78.7 ± 7.8 | 78.7 ± 7.9 |

| BMI (kg m–2) | 24.4 ± 2.3 | 24.5 ± 2.3 | 24.6 ± 2.2 | 24.5 ± 2.3 |

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index

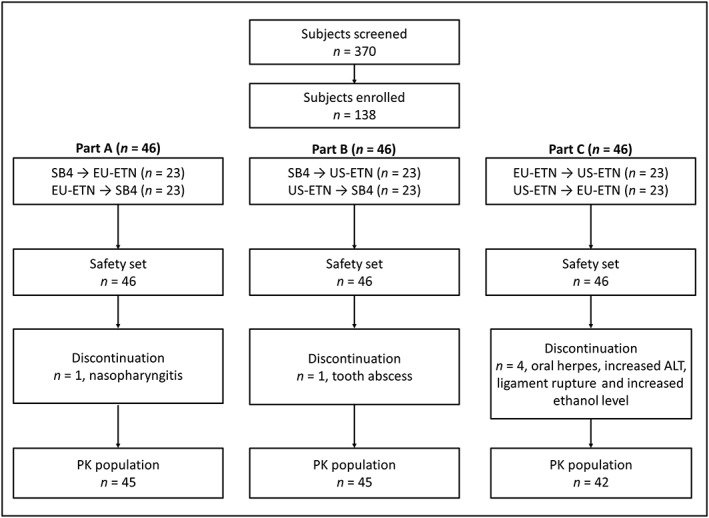

Of the 138 subjects, six subjects discontinued the study before the start of period 2 (part A: one subject; part B: one subject; part C: four subjects). Among them, only two subjects discontinued the study because of treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs) related to the treatments in part C: one reported oral herpes of moderate severity after EU‐ETN administration, and the other had a clinically significant increase in alanine transaminase (ALT) after EU‐ETN administration. The other four subjects discontinued owing to TEAEs not related to the treatments (nasopharyngitis, a tooth abscess and a ligament rupture) or subject noncompliance (because the subject consumed excessive quantities of alcohol during the study). There was no subject discontinuation during period 2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of subject disposition. All enrolled subjects were included in the safety analysis. Among them, subjects who completed both period 1 and period 2 were included in the PK analysis. ALT, alanine transaminase

PK results

Of the 132 subjects who completed the study, three individuals in part A and one in part B were excluded from the PK analysis owing to baseline concentrations of greater than 5% of C max in period 2 following the guidelines of bioequivalence studies 14, 16. The exclusion of these subjects was expected to have no significant impact on the results because individual PK parameters were distributed around their median values in period 2.

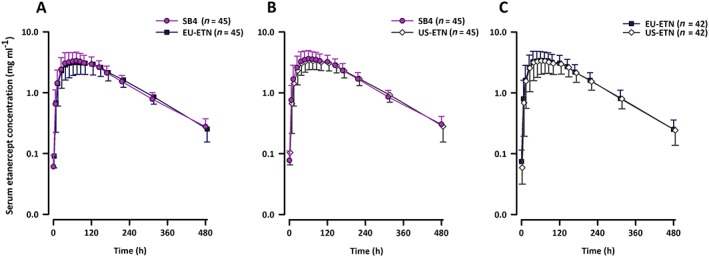

The mean serum concentration–time profiles were superimposable between the two treatments in each part of the study (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean (SD) serum concentration of etanercept after single 50 mg subcutaneous dose of (A) SB4 or EU‐ETN in part A; (B) SB4 or US‐ETN in part B; and (C) EU‐ETN vs. US‐ETN in part C. SD, standard deviation

The mean values of the PK parameters, including AUCinf, AUClast, C max, T max, Vz/F, half‐life and CL/F, were similar between the two treatments in each part (Table 2). The geometric LSMeans ratios (90% CI) for AUCinf, AUClast and C max were 99.04% (94.71–103.58%), 98.62% (94.17–103.28%) and 103.71% (98.46–109.25%) between SB4 and EU‐ETN in part A; 101.09% (95.75–106.73%), 100.96% (95.37–106.87%) and 104.36% (97.74–111.41%) between SB4 and US‐ETN in part B; and 100.51% (91.48–110.42%), 101.27% (92.34–111.06%) and 103.29% (94.70–112.66%) between EU‐ETN and US‐ETN in part C. The corresponding 90% CIs were completely contained within the equivalence margin of 80–125% (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the pharmacokinetic parameters (mean ± SD)

| Part A | Part B | Part C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB4 | EU‐ETN | SB4 | US‐ETN | EU‐ETN | US‐ETN | |

| Subject (n) | 42 | 42 | 44 | 44 | 42 | 42 |

| AUCinf (μg h ml–1) | 769 ± 244 | 772 ± 226 | 835 ± 243 | 810 ± 196 | 790 ± 274 | 768 ± 238 |

| AUClast (μg h ml–1) | 728 ± 235 | 734 ± 220 | 789 ± 232 | 765 ± 185 | 752 ± 259 | 728 ± 230 |

| Cmax (μg ml–1) | 3.61 ± 1.43 | 3.44 ± 1.24 | 3.87 ± 1.33 | 3.61 ± 1.03 | 3.72 ± 1.54 | 3.58 ± 1.48 |

| Tmax (h)† | 72 (36–146) | 72 (36–144) | 72 (24–144) | 60 (36–120) | 60 (24–144) | 60 (24–120) |

| Vz/F (l) | 11.2 ± 4.7 | 10.5 ± 4.7 | 10.3 ± 4.7 | 9.6 ± 2.9 | 10.1 ± 4.9 | 10.5 ± 4.5 |

| t½ (h) | 106 ± 12 | 100 ± 16 | 106 ± 9 | 101 ± 17 | 95 ± 18 | 100 ± 19 |

| CL/F (ml h–1) | 72.9 ± 27.5 | 71.5 ± 24.8 | 67.0 ± 27.8 | 65.7 ± 17.6 | 77.3 ± 54.1 | 71.3 ± 22.4 |

Four subjects (three subjects in part A and one subject in part B) were excluded owing to a carry‐over effect. AUCinf, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero extrapolated to infinity; AUClast, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to the last quantifiable concentration; C max, maximum concentration; T max, time to reach Cmax;CL/F, apparent clearance; t ½, terminal half‐life; US‐ETN, Vz/F, apparent volume of distribution; SD, standard deviation. †Median (Min‐Max).

Table 3.

Statistical comparison of primary pharmacokinetic parameters between the test and reference products

| Treatment | Geometric LSMeans | Ratio (%) | Intra‐CV (%) | 90% CI (%) (lower; upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part A: SB4 vs. EU‐ETN (n = 42) | |||||

| AUCinf (μg h ml–1) | SB4 | 729 | 99.04 | 12.22 | 94.71; 103.58 |

| EU‐ETN | 736 | ||||

| AUClast (μg h ml–1) | SB4 | 689 | 98.62 | 12.60 | 94.17; 103.28 |

| EU‐ETN | 698 | ||||

| Cmax (μg ml–1) | SB4 | 3.32 | 103.71 | 14.21 | 98.46; 109.25 |

| EU‐ETN | 3.20 | ||||

| Part B: SB4 vs. US‐ETN (n = 44) | |||||

| AUCinf (μg h ml–1) | SB4 | 794 | 101.09 | 15.22 | 95.75; 106.73 |

| US‐ETN | 786 | ||||

| AUClast (μg h ml–1) | SB4 | 750 | 100.96 | 15.97 | 95.37; 106.87 |

| US‐ETN | 742 | ||||

| Cmax (μg ml–1) | SB4 | 3.61 | 104.36 | 18.41 | 97.74; 111.41 |

| US‐ETN | 3.46 | ||||

| Part C: EU‐ETN vs. US‐ETN (n = 42) | |||||

| AUCinf (μg h ml–1) | EU‐ETN | 735 | 100.51 | 26.00 | 91.48; 110.42 |

| US‐ETN | 732 | ||||

| AUClast (μg h ml–1) | EU‐ETN | 701 | 101.27 | 25.49 | 92.34; 111.06 |

| US‐ETN | 692 | ||||

| Cmax (μg ml–1) | EU‐ETN | 3.41 | 103.29 | 23.94 | 94.70; 112.66 |

| US‐ETN | 3.30 | ||||

Four subjects (three subjects in part A and one subject in part B) were excluded owing to carry‐over effect. AUCinf, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero extrapolated to infinity; AUClast, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to the last quantifiable concentration; CI, confidence interval; C max, maximum concentration; LSMeans, least squares means; Intra‐CV, intrasubject coefficient of variation.

Safety results

Data from all 138 subjects enrolled in the study were evaluated for safety. TEAEs, regardless of causality, were reported from 41 (44.6%), 33 (35.9%) and 34 (37.0%) subjects treated by SB4, EU‐ETN, and US‐ETN, respectively (Table 4). In each part, the proportions of subjects who experienced the TEAEs were also comparable between the treatments (Table S2). The majority of the TEAEs reported were mild or moderate in severity, except for two cases of severe diarrhoea after EU‐ETN administration and a severe ligament rupture after US‐ETN administration. Those severe TEAEs were considered by the investigator to be unrelated to the treatment.

Table 4.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events, regardless of causality, that occurred in ≥5% of subjects in any treatment

| SB4 | EU‐ETN | US‐ETN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 92 | 92 | 92 |

| Subjects with any TEAEs, n (%) | 41 (44.6) | 33 (35.9) | 34 (37.0) |

| Infections and infestations, n (%) | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (7.6) | 4 (4.3) | 3 (3.3) |

| Nervous system disorders, n (%) | |||

| Dizziness | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.3) |

| Headache | 7 (7.6) | 6 (6.5) | 7 (7.6) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions, n (%) | |||

| Injection site reaction | 5 (5.4) | 4 (4.3) | 6 (6.5) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, n (%) | |||

| Back pain | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.3) |

SB4, summary for subjects receiving SB4 from part A and part B; EU‐ETN, summary for subjects receiving EU‐ETN from part A and part C; US‐ETN, summary for subjects receiving US‐ETN from part B and part C; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event. Dizziness and back pain occurred more frequent than 5% in one of the three study parts (see also Table S2).

The number of subjects who experienced TEAEs related to SB4 treatment was 29 (31.5%), to EU‐ETN treatment was 25 (27.2%) and to US‐ETN treatment was 27 (29.3%). The most common treatment–related TEAE across the treatments (17 subjects) was headache. There were no serious AEs (SAEs) or deaths reported during the study.

Vital signs, physical examination, clinical laboratory tests and 12‐lead ECG results did not show significant changes over time that might be considered related to the treatments.

Immunogenicity results

In part A, three subjects were confirmed to be positive for ADA after EU‐ETN administration. Among them, only one subject had a positive result for NAb. In part B, four subjects were confirmed positive for ADA after US‐ETN administration, and none of the subjects had a positive result for NAb. In part C, four subjects were confirmed positive for ADA after EU‐ETN administration, and six subjects after US‐ETN administration. None of the subjects in part C had a positive result for NAb.

Discussion

Comparative PK studies are considered to be essential for demonstrating biosimilarity between the biosimilar and the reference product. The study design depends on various factors, including the clinical context, safety and PK characteristics of the product. Generally, from a PK perspective, a single‐dose crossover study with full characterization of the PK profile in a sufficiently sensitive and homogeneous population is recommended 9.

The present study was a single‐dose, three‐part, 2 × 2 crossover study to compare three products in healthy male subjects. The crossover design allowed each subject to receive both treatments, so that a comparison between the two treatments could be made on the same subject. This crossover design therefore required fewer subjects than a parallel study design to prove PK equivalence. Although the Williams design, which consists of three treatments and three periods (3 × 3) in six sequences, is an ideal choice when there are more than two treatments in a bioequivalence study 17, the design may not be appropriate for biological products because of their relatively longer half‐life compared with chemical products. The half‐life of ETN has been reported as approximately 70 h, with range from 7 h to 300 h 8. Usually, the length of the washout period between the drug administrations should be more than five half‐lives of the drug. The maintenance of subject compliance with the protocol‐specified controlled conditions (e.g. schedule of in‐house and ambulant visit, and restrictions on alcohol and physical exercise) became more difficult with increased study duration 18. Thus, three 2 × 2 crossover studies were more appropriate than one 3 × 3 crossover study to compare three biological products in a pairwise manner. Healthy male subjects were considered to be a more homogeneous population than RA patients with various disease‐related factors and taking concomitant medications that might influence the PK profiles of the products. This selected population was expected to reduce variability that was unrelated to differences between the products, thereby simplifying the interpretation of PK equivalence. This study design and target population were consulted with both the EMA and FDA prior to the start of the study.

The PK results of the present study can be extrapolated to the female population because no clinically relevant difference in the CL of ETN was found between men and women in a population modelling study 19. The treatment dose (50 mg) used in the present study is the highest labelled dose recommended in the respective guideline 14. Dose proportionality of ETN for 10 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg doses has been shown in healthy volunteers 20. Comparable exposure between 25 mg twice weekly and 50 mg once weekly dosing was also demonstrated after a single dose and at steady state 13, 21, 22. Therefore, similar PK profiles were expected between SB4 and ETN with a different dosing schedule.

SB4 and the two reference products exhibited similar PK profiles, showing slow absorption from the site of subcutaneous injection (average range of T max: 70–75 h) and slow elimination (average range of half‐life: 95–106 h), which is in line with known PK characteristics of ETN 23, 24. PK equivalence in terms of AUCinf, AUClast, and C max was successfully demonstrated for all pairwise comparisons in parts A, B and C. The intrasubject variability, which is product dependent, in PK parameters was 12–14% between SB4 and EU‐ETN, 15–18% between SB4 and US‐ETN, and 24–26% between EU‐ETN and US‐ETN (Table 3). These data imply that the differences in PK between SB4 and either of the two reference products are smaller than those between the EU‐sourced and US‐sourced reference products.

In the present study, there was one test product, SB4, and two reference products, EU‐ETN and US‐ETN. The regulatory agencies require data that directly compare the proposed product with the regulatory approved or licensed reference product 9, 11. The comparisons between SB4 and EU‐ETN from part A and between SB4 and US‐ETN in part B were carried out to meet the EMA and FDA requirements, respectively. Additionally, the comparison between EU‐ETN and US‐ETN in part C was evaluated to provide scientific justification for the use of EU‐ETN, which is not licensed in the USA as the active comparator in the clinical phase III study. These three pairwise comparisons between the products were conducted directly in each separate study. Ring et al. proposed indirect comparison analysis using the bridging method to determine the bioequivalence of formulations not tested within the same clinical trial 25. In fact, this method provides similar 90% CIs for all comparisons with the results presented in Table 3 (see also Table S3).

All three treatments were generally well tolerated, with no SAEs or deaths reported during the study. The majority of the TEAEs were well distributed between the treatments. The most common TEAE across all treatments was headache, which was consistent with previously reported comparative PK studies in healthy subjects 13, 23. Five subjects discontinued the study owing to TEAEs. Among them, two subjects experienced TEAEs related to the treatments. One of these reported moderate oral herpes on day 23 after EU‐ETN administration in period 1. The oral herpes was resolved 14 days after onset of the TEAE without any rescue medication. The other subject reported a clinically significant increase in ALT values to 160.7 U l–1 (normal range: 0–50 U l–1) on day 21 after EU‐ETN administration in period 1. This increase in ALT returned to the normal value (40 U l–1) 12 days later. Infections are very common adverse events after using ETN 8. However, nasopharyngitis and tooth abscess were assessed by investigator to be unrelated to the treatment. Nasopharyngitis was reported on day 26 by a subject receiving SB4 in period 1. The subject experienced an elevated C‐reactive protein level of 12.17 mg l–1 (normal range 0–5 mg l–1). Although the investigator considered that the AE was not related to the treatment, the subject was discontinued as his C‐reactive protein level did not meet the predefined criteria for the second dose. The tooth abscess was reported by a subject receiving US‐ETN. The subject experienced inflammatory facial swelling and was withdrawn from the study according to predefined subject dropout criteria. He had undergone tooth implant surgery on the left side of the jaw about 2 months earlier but had not provided this history at screening. The investigator considered that the event was not caused by the treatment but by his medical history. The ligament rupture was reported by a subject receiving US‐ETN. He had played soccer during the washout period and experienced torsion of the knee. He had had to start heparin therapy and use a crutch owing to his injury. The investigator considered that the event was not related to the treatment, and that his further participation in the study was not appropriate.

Immunogenicity was evaluated predose and at day 29 after the first treatment. No subjects who received SB4 developed ADA but 15.6% of subjects who received EU‐ETN (P = 0.006 for SB4 vs. EU‐ETN) and 22.7% of subjects who received US‐ETN (P < 0.001 for SB4 vs. US‐ETN) developed ADA across the parts. Although a single‐dose study in a limited number of healthy subjects was not enough to evaluate the immunogenicity between SB4 and ETN, the low incidence of ADA following administration of SB4 was consistent with the long‐term immunogenicity results in RA patients, in whom the incidence of ADA following multiple doses was 0.7% in the SB4 treatment group and 13.1% in ETN treatment group over a 24‐week period (P < 0.001) 26. There are product‐specific factors that known to affect immunogenicity, such as product origin (foreign or human), product aggregates, impurities, glycosylation, formulation and the container closure system 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33. Among these, factors contributing to the lower immunogenicity profile of SB4 compared with ETN should be investigated in future studies. Additional subgroup analysis of PK using ANOVA, and of the type and frequency of AEs reported in a subset of subjects with negative ADA results showed that there was no marked impact of immunogenicity on PK and safety in the present study (data not shown).

The present clinical phase I study demonstrated PK equivalence between SB4 and ETN in healthy male subjects. In addition, SB4 was well tolerated, with a lower immunogenicity profile. The safety profile of SB4 was comparable with that of ETN. The clinical phase III study to demonstrate similarity in efficacy, safety, immunogenicity and PK between SB4 and ETN in RA patients was also completed successfully 26. Based on the results of the data in healthy male subjects and RA patients, SB4 has been approved as the first ETN biosimilar in the EU

Competing Interests

All of the authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that this study was funded by Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd., Incheon, Republic of Korea. All of the authors are employees of either Samsung Bioepis or of an organization contracted by Samsung Bioepis for the present study. There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to influence the submitted work.

Contributors

YL and DS designed the research study; RF and AG were investigators in the clinical trial; YK and JK analysed the data; YL wrote the paper

Supporting information

Table S1 Demographic characteristics of the subjects (Mean±SD)

Table S2 Treatment‐emergent adverse events regardless of the causality that occurred in ≥ 5% of subjects in any treatment in each part

Table S3 Indirect comparison of primary PK parameters between the test and reference products

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Lee, Y. J. , Shin, D. , Kim, Y. , Kang, J. , Gauliard, A. , and Fuhr, R. (2016) A randomized phase l pharmacokinetic study comparing SB4 and etanercept reference product (Enbrel®) in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 82: 64–73. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12929.

References

- 1. Mohler KM, Torrance DS, Smith CA, Goodwin RG, Stremler KE, Fung VP, Madani H, Widmer MB. Soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors are effective therapeutic agents in lethal endotoxemia and function simultaneously as both TNF carriers and TNF antagonists. J Immunol 1993; 151: 1548–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moreland LW, Baumgartner SW, Schiff MH, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM, Weaver AL, Ettlinger RE, Cohen S, Koopman WJ, Mohler K, Widmer MB, Blosch CM. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75)‐Fc fusion protein. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM, Bulpitt KJ, Weaver AL, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Mease PJ, Ruderman EM, Horwitz DA, Arkfeld DG, Garrison L, Burge DJ, Blosch CM, Lange ML, McDonnell ND, Weinblatt ME. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, Bulpitt KJ, Fleischmann RM, Fox RI, Jackson CG, Lange M, Burge DJ. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, VanderStoep A, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet 2000; 356: 385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korth‐Bradley JM, Rubin AS, Hanna RK, Simcoe DK, Lebsack ME. The pharmacokinetics of etanercept in healthy volunteers. Ann Pharmacother 2000; 34: 161–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nestorov I, Zitnik R, DeVries T, Nakanishi AM, Wang A, Banfield C. Pharmacokinetics of subcutaneously administered etanercept in subjects with psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 62: 435–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ENBREL®[etanercept] . Summary of product characteristics, 2014.

- 9. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) . Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing monoclonal antibodies – non clinical and clinical issues. European Medicines Agency, 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2012/06/WC500128686.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) . Guideline on similar biological medicinal product. European Medicines Agency, 2005. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003517.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research . Guidance for industry: scientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/DrugsGuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM291128.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Benepali: Assessment report. 2015. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Public_assessment_report/human/004007/WC500200380.pdf

- 13. Sullivan JT, Ni L, Sheelo C, Salfi M, Peloso PM. Bioequivalence of liquid and reconstituted lyophilized etanercept subcutaneous injections. J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 46: 654–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) . Guideline on the investigation of bioequivalence. European Medicines Agency, 2010. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/01/WC500070039.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research . Guidance for industry: statistical approaches to establishing bioequivalence. US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/ucm070244.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research . Guidance for industry: bioavailability and bioequivalence studies submitted in NDAs or INDs – general considerations. US Department of Health and Human Service, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm389370.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17. William EJ. Experimental designs balanced for the estimation of residual effects of treatments. Aust J Chem 1949; 2: 149–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marzo A. Open questions on bioequivalence: some problems and some solutions. Pharmacol Res 1999; 40: 357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of etanercept: a fully humanized soluble recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein. J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 45: 490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawai S, Sekino H, Yamashita N, Tsuchiwata S, Liu H, Korth‐Bradley JM. The comparability of etanercept pharmacokinetics in healthy Japanese and American subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 46: 418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keystone EC, Schiff MH, Kremer JM, Kafka S, Lovy M, DeVries T, Burge DJ. Once‐weekly administration of 50 mg etanercept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elewski B, Leonardi C, Gottlieb AB, Strober BE, Simiens MA, Dunn M, Jahreis A. Comparison of clinical and pharmacokinetic profiles of etanercept 25 mg twice weekly and 50 mg once weekly in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gu N, Yi S, Kim TE, Shin SG, Jang IJ, Yu KS. Comparative pharmacokinetics and tolerability of branded etanercept (25 mg) and its biosimilar (25 mg): a randomized, open‐label, single‐dose, two‐sequence, crossover study in healthy Korean male volunteers. Clin Ther 2011; 33: 2029–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yi S, Kim SE, Park MK, Yoon SH, Cho JY, Lim KS, Shin SG, Jang IJ, Yu KS. Comparative pharmacokinetics of HD203, a biosimilar of etanercept, with marketed etanercept (Enbrel®): a double‐blind, single‐dose, crossover study in healthy volunteers. BioDrugs 2012; 26: 177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ring A, Morris TB, Hohl K, Schall R. Indirect bioequivalence assessment using network meta‐analyses. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 70: 947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Emery P, Vencovský J, Sylwestrzak A, Leszczyński P, Porawska W, Baranauskaite A, Tseluyko V, Zhdan VM, Stasiuk B, Milasiene R, Rodriguez AAB, Cheong SY, Ghil J. A phase III randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group study comparing SB4 with etanercept reference product in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; (epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh SK. Impact of product‐related factors on immunogenicity of biotherapeutics. J Pharm Sci 2011; 100: 354–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hermeling S, Crommelin DJ, Schellekens H, Jiskoot W. Structure–immunogenicity relationships of therapeutic proteins. Pharm Res 2004; 21: 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosenberg AS. Effects of protein aggregates: an immunologic perspective. AAPS J 2006; 8: E501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noguchi A, Mukuria CJ, Suzuki E, Naiki M. Immunogenicity of N‐glycolylneuraminic acid‐containing carbohydrate chains of recombinant human erythropoietin expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biochem 1995; 117: 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sheeley DM, Merrill BM, Taylor LC. Characterization of monoclonal antibody glycosylation: comparison of expression systems and identification of terminal alpha‐linked galactose. Anal Biochem 1997; 247: 102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Qian J, Liu T, Yang L, Daus A, Crowley R, Zhou Q. Structural characterization of N‐linked oligosaccharides on monoclonal antibody cetuximab by the combination of orthogonal matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization hybrid quadrupole–quadrupole time‐of‐flight tandem mass spectrometry and sequential enzymatic digestion. Anal Biochem 2007; 364: 8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flynn GC, Chen X, Liu YD, Shah B, Zhang Z. Naturally occurring glycan forms of human immunoglobulins G1 and G2. Mol Immunol 2010; 47: 2074–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Demographic characteristics of the subjects (Mean±SD)

Table S2 Treatment‐emergent adverse events regardless of the causality that occurred in ≥ 5% of subjects in any treatment in each part

Table S3 Indirect comparison of primary PK parameters between the test and reference products

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item