Abstract

Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg strains (JF6X01.0022/XbaI.0251, JF6X01.0326/XbaI.1966, JF6X01.0258/XbaI.1968, and JF6X01.0045/XbaI.1970) have been identified in the United States with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Our examination of isolates showed introduction of these strains in the Netherlands and highlight the need for active surveillance and intervention strategies by public health organizations.

Keywords: Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, AmpC, IncI1 plasmids, the Netherlands, bacteria, antibacterial agents, Salmonella infections, antimicrobial resistance

Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg is among the most prevalent causes of human salmonellosis in the United States and Canada but has been reported infrequently in Europe (1–3). Although most nontyphoidal Salmonella infections are self-limiting and resolve within a few days, Salmonella ser. Heidelberg tends to provoke invasive infections (e.g., myocarditis and bacteremia) that require antimicrobial drug therapy (4). To treat systemic nontyphoidal Salmonella infections, third-generation cephalosporins are preferred drugs for children or for adults with fluoroquinolone contraindications (5). Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins is increasing in S. enterica infections, mainly because of production of plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum or AmpC β-lactamases (6).

Resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) among Salmonella Heidelberg strains found in human infections, food-producing animals, and poultry meat indicates zoonotic and foodborne transmission of these strains and potential effects on public health (7,8). Unlike in Canada and the United States, few ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strains have been documented in Europe (9–13). However, increased occurrence of ESC resistance in S. enterica infections and decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones compromise the use of these drugs and constitute a serious public health threat (6,14).

Few data are available regarding prevalence of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates in Europe, their underlying antimicrobial drug resistance gene content, and genetic platforms (i.e., plasmids and insertion sequence [IS] elements) associated with resistance genes. We attempted to determine the occurrence and molecular characteristics of Salmonella Heidelberg isolates recovered from human patients, food-producing animals, and poultry meat in the Netherlands during 1999–2013.

The Study

During 1999–2013, the Netherlands National Institute of Public Health and the Environment collected 437 Salmonella Heidelberg isolates from human infections (n = 77 [17.6%]), food-producing animals (n = 138 [31.6%]), poultry meat (n = 170 [38.9%]), and other sources (n = 52 [11.9%]). From this collection, we selected 200 epidemiologically unrelated isolates for further analysis (Table; Technical Appendix).

Table. Characteristics of Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolates recovered from human infections, food-producing animals, poultry meat, and other sources, the Netherlands, 1999–2013*.

| Source | 1999–2001 | 2002–2004 | 2005–2007 | 2008–2010 | 2011–2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human infections | |||||

| No. isolates studied | 13 | 10 | 22 | 23 | 15 |

| Resistance phenotypes (no.) | Amp (1), AmpCol (1), AmpSmxTmpStr (1), AmpTetSmxTmpStr (1), SmxStr (1), Str (5), TetSmxTmpStr (1), WT (2) | AmpSmxStr (1), AmpTetSmx (1), SmxStr (3), Str (1), TetSmxStr (1), WT (3) | AmpFotTazStr (1), AmpSmxTmpNalCip (1), AmpTet (1), NalCip (2), SmxStr (1), Tet (1), TetSmxNalCip (1), WT (14) | ChlCol (1), Col (10), Str (1), StrCol (5), TetCol (1), TetNalCip (1), TetSmxTmp StrCol (1), TetStr KanCol (1), TetStr SmxCol (1), WT (1) | Col (1), Str (3), TetSmxStr (2), TetSmxTmp (1), WT (8) |

| No. ESCR isolates |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Food-producing animals | |||||

| No. isolates studied | 5 | 16 | 5 | 7 | 13 |

| Resistance phenotypes (no.) | NalCip (1), WT (4) | Amp (3), AmpSmxTmpNalCipStr (2), AmpStr (2), NalCip (5), SmxStrTmp (1), WT (3) | AmpTetSmxTmpNalCip (1), WT (4) | AmpCol (1), AmpFotTazNalCip (1), AmpFotTazTetSmx GenStrKanCol (1), Col (4) | AmpCol (1), AmpFotTazTetSmx (1), AmpFotTazTet SmxNalCip (4), Col (2), TetSmxNalCip (2), TetSmxNal CipGenStrKan (1), WT (2) |

| No. ESCR isolates |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

| Poultry meat | |||||

| No. isolates studied | 3 | 3 | 15 | 6 | 40 |

| Resistance phenotypes (no.) | AmpTetSmxTmpNalCipStr (1), SmxTmpStr (1), WT (1) | AmpSmxStr (1), WT (2) | NalCip (3), SmxCipGen (1), SmxGen (1), SmxTmpNalCip (1), TetSmxTmp (1), WT (8) | AmpFotTaz (1), AmpFotTazSmxTmp ChlStrCol (1), AmpFotTazStrCol (1), Col (2), NalCipCol (1) | AmpFotTazTetSmx NalCip (26), AmpFotTazTetSmx NalCipCol (1), AmpFotTazTetSmx NalCipGenStrKan (1), AmpFotTaz TetSmxNalCipStr (6), AmpFotTazTetSmx TmpNalCipChl (1), Col (2), TetSmx NalCip (1), TetSmx NalCipGenStr (1), TetSmxNalCipStr (1) |

| No. ESCR isolates |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

35 |

| Other | |||||

| No. isolates studied | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| Resistance phenotypes (no.) | WT (1) | Col (2), NalCipCol (1), Str (1), StrCol (2) | AmpFotTazTetSmx NalCip (1), NalCipCol (1), Str (1), TetSmxNal CipGenStr (1) | ||

| No. ESCR isolates | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

*Amp, ampicillin; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Col, colistin; ESCR, extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant; Fot, cefotaxime; Gen, gentamicin; Kan, kanamycin; Nal, nalidixic acid; Smx, sulfamethoxazole; Str, streptomycin; Taz, ceftazidime; Tet, tetracycline; Tmp, trimethoprim; WT, wild type.

MICs for antimicrobial agents were determined with the broth microdilution method (online Technical Appendix) and showed a higher frequency of multidrug non–wild-type susceptibility phenotype in isolates from poultry meat (n = 44 [68.8%]) than in isolates from food-producing animals (n = 14 [31.8%]) and human infections (n = 16 [19.5%]). Most human infections exhibited wild-type MICs to most antimicrobial agents tested (Table).

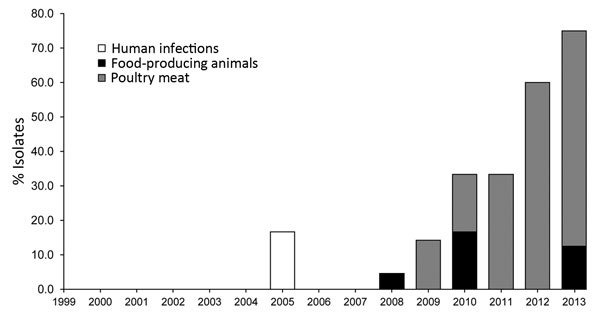

Of the 200 Salmonella Heidelberg isolates in the study, 47 (23.5%) were ESC resistant. ESC resistance in Salmonella Heidelberg isolates increased from 33.3% in 2011 to 60.0% in 2012 to 75.0% in 2013, after which Salmonella Heidelberg was the predominant serotype in ESC-resistant Salmonella isolates in the Netherlands (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Occurrence of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolates, the Netherlands, 1999–2013.

These isolates showed MICs for cefotaxime and ceftazidime of 2 to >4 mg/L and 4 to >16 mg/L, respectively; non–wild-type susceptibility to fluoroquinolones was 87.2%. The emergence of isolates with decreased susceptibility to these first-line antimicrobial drugs limits effective treatment options for potential human infections.

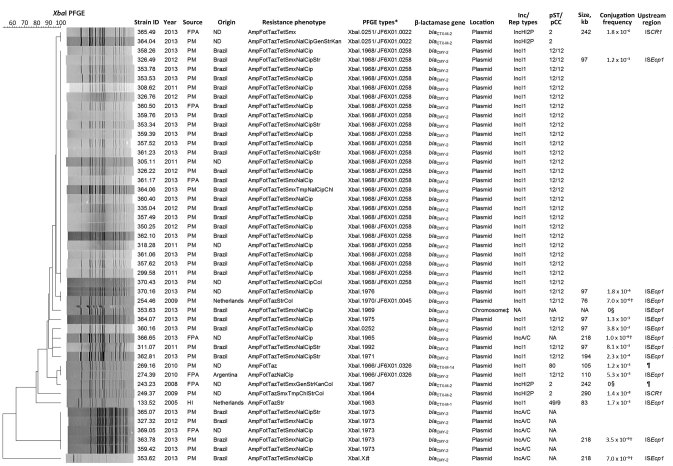

ESC typing of the 47 isolates, performed by microarray analysis followed by PCR and sequencing (Technical Appendix), revealed the presence of the blaCMY-2 gene in 41 ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates that exhibited an AmpC β-lactamase phenotype. The other 6 isolates exhibited an extended-spectrum β-lactamase phenotype and encoded blaCTX-M-2 (n = 4), blaCTX-M-1 (n = 1), or blaCTX-M-14 (n = 1) genes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolates, the Netherlands, 1999–2013. The dendrogram was generated by using BioNumerics version 6.6 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) and indicates results of a cluster analysis on the basis of XbaI–pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) fingerprinting. Similarity between the profiles was calculated with the Dice similarity coefficient and used 1% optimization and 1% band tolerance as position tolerance settings. The dendrogram was constructed with the UPGMA method based on the resulting similarity matrix. Amp, ampicillin; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Col, colistin; Fot, cefotaxime; FPA, food-producing animals; Gen, gentamicin; HI, human infection; Kan, kanamycin; Nal, nalidixic acid; ND, not determined (i.e., refers to isolates recovered in the Netherlands but with unknown origin of the sample); pCC, plasmid clonal complex; PM, poultry meat; pST, plasmid sequence type; Smx, sulfamethoxazole; Str, streptomycin; Taz, ceftazidime; Tet, tetracycline; Tmp, trimethoprim. *Pattern numbers assigned by The European Surveillance System molecular surveillance service of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control database and corresponding pattern numbers from the PulseNet database (http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/index.html). †Results refer to the conjugation frequencies during filter-mating experiments. ‡Chromosomal location confirmed by I-CeuI PFGE of total bacterial DNA, followed by Southern blot hybridization. §No transconjugants were obtained after liquid and filter-mating experiments, suggesting the presence of nonconjugative plasmids or conjugation frequencies below detection limits. ¶Insertion sequences ISEcp1, ISCR1, or IS26 were not found upstream of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes for these PFGE types. #This PFGE fingerprint was not submitted to The European Surveillance System molecular surveillance service of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control database for name assignment.

We assessed the genetic relatedness of the 47 cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates by using the standardized XbaI–pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (online Technical Appendix), which identified 2 major PFGE types: XbaI.1968 and XbaI.1973 (PFGE numbers assigned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Solna, Sweden). Of the 47 isolates, 26 (55.3%) belonged to XbaI.1968 and 5 (10.6%) belonged to XbaI.1973. Forty-one of the isolates were blaCMY-2 carriers, 31 (75.6%) of which belonged to these 2 PFGE types; 10 (24.4%) were distributed equally among other PFGE types. Six of the 47 isolates were blaCTX-M carriers associated with 5 PFGE types (Figure 2). Comparing these isolates with those in the PulseNet database (http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/index.html) revealed the introduction of 4 epidemic clones of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strains in the Netherlands (JF6X01.0022/XbaI.0251, JF6X01.0326/XbaI.1966, JF6X01.0258/XbaI.1968, and JF6X01.0045/XbaI.1970). To raise awareness and determine whether related ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates had been observed in other European countries, the Epidemic Intelligence Information System (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) issued an alert on September 18, 2014.

We successfully transferred plasmids carrying extended-spectrum or AmpC β-lactamases from ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates to the recipient E. coli DH10B strain (Technical Appendix). PCR-based Inc/Rep typing and multilocus or double-locus sequence typing (ST) of the plasmids revealed that the blaCMY-2 or blaCTX-M genes were located on plasmids for 46 (97.8%) of the 47 isolates. ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates encoding blaCMY-2 on IncI1/ST12 plasmids were associated predominantly with the XbaI.1968 (n = 26 [78.8%]) PFGE type; those encoding blaCMY-2 on IncA/C plasmids were associated with XbaI.1973 (n = 5 [71.4%]). Isolates encoding blaCTX-M-2 on IncHI2P/ST2, blaCTX-M-1 on IncI1/ST49, and blaCTX-M-14 on IncI1/ST80 plasmids were associated with XbaI.1964, XbaI.1963, and XbaI.1966, respectively (Figure 2).

The blaCMY-2 gene was present in 12 different PFGE types and was carried on plasmids of 2 different incompatibility groups (IncI1/ST12 and IncA/C) or on the chromosome. This gene’s diverse genetic background suggests that emergence of the blaCMY-2–producing Salmonella Heidelberg strain in the Netherlands results not only from expansion of a single clone but from multiclonal dissemination of the strain and horizontal transfer of plasmids encoding the blaCMY-2 gene. IncI1/ST12 and IncA/C plasmids have been associated with the blaCMY-2 gene in Salmonella Heidelberg isolates in the United States and Canada (8,15).

We analyzed a subset of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates to determine the size and conjugation frequency of plasmids carrying extended-spectrum and AmpC β-lactamases. We also assessed a subset of Salmonella Heidelberg isolates (n = 17) for each PFGE type, including isolates for each type if they showed variation in extended-spectrum and AmpC β-lactamase genes or in gene location. This assessment sought to detect the upstream presence of resistance genes (blaCTX-M and blaCMY) of frequently encountered insertion sequences (ISEcp1, ISCR1, and IS26) (Figure 2; Technical Appendix).

We attribute the increase of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates in the Netherlands to the frequent occurrence of isolates carrying IncI1/ST12 plasmids encoding blaCMY-2 in food-producing animals and poultry products imported from Brazil. Isolates from imported poultry products are associated predominantly with PFGE types XbaI.1968 and XbaI.1973 (Figure 2). A similar introduction of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strains in Ireland was associated with imported poultry meat from Brazil (R. Slowey, pers. comm.). Although ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strains are rarely reported in Europe, their introduction through imported poultry meat could pose a public health risk; Brazil is among the world’s leading countries for exporting poultry meat.

Conclusions

Most ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates in our study had profiles (XbaI.0251, XbaI.1966, XbaI.1968, and XbaI.1970) indistinguishable from those of previous epidemic types (JF6X01.0022, JF6X01.0326, JF6X01.0258, and JF6X01.0045) that caused outbreaks and showed potency for bloodstream infections (16). Our identification of clonal clusters shared by ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strains in food-producing animals or poultry meat that can cause human infections underscores the risk for potential zoonotic or foodborne transmission of these strains to humans.

Although we observed a frequent occurrence of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg isolates in poultry products, no human infections linked to these contaminated products have been yet documented in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, the risk of potential zoonotic or foodborne transmission of ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strains highlights the necessity for active surveillance and intervention strategies by public health organizations.

Detailed methods and materials used in study of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg strains, the Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Johanna Takkinen, Ivo van Walle, and the curators of The European Surveillance System molecular surveillance service of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control database for assigning reference type and pattern names to our PFGE types. We are also grateful to Patrick McDermott and Jason Abbott for helping with comparing our PFGE types with those from the PulseNet database; we also thank John Egan and Rosemarie Slowey for providing information about the ESC-resistant S. enterica ser. Heidelberg strains detected in Ireland.

This work was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs (BO-22.04-008-001).

Biography

Mr. Liakopoulos is a junior scientist at the Central Veterinary Institute, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. His research interests include the genetic basis of antimicrobial drug resistance and the molecular epidemiology of antimicrobial drug–resistant human pathogens.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Liakopoulos A, Geurts Y, Dierikx CM, Brouwer MSM, Kant A, Wit B, et al. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg strains, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jul [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2207.151377

Preliminary results from this study were presented at the 12th Beta-Lactamase Meeting, June 28–July 1, 2014, Gran Canaria, Spain.

References

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Technical document. EU protocol for harmonised monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in human Salmonella and Campylobacter isolates. Stockholm: The Centre; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada. National Enteric Surveillance Program (NESP). Annual summary 2012. Ottawa (Ontario, CA): The Agency; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: enteric bacteria. 2012 Human isolates final report. Atlanta: The Centers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann M, Zhao S, Pettengill J, Luo Y, Monday SR, Abbott J, et al. Comparative genomic analysis and virulence differences in closely related Salmonella enterica serotype Heidelberg isolates from humans, retail meats, and animals. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:1046–68. 10.1093/gbe/evu079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acheson D, Hohmann EL. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:263–9. 10.1086/318457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miriagou V, Tassios PT, Legakis NJ, Tzouvelekis LS. Expanded-spectrum cephalosporin resistance in non-typhoid Salmonella. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;23:547–55. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutil L, Irwin R, Finley R, Ng LK, Avery B, Boerlin P, et al. Ceftiofur resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg from chicken meat and humans, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:48–54. 10.3201/eid1601.090729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folster JP, Pecic G, Singh A, Duval B, Rickert R, Ayers S, et al. Characterization of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolated from food animals, retail meat, and humans in the United States 2009. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9:638–45. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aarestrup FM, Hasman H, Olsen I, Sørensen G. International spread of blaCMY-2–mediated cephalosporin resistance in a multiresistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolate stemming from the importation of a boar by Denmark from Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1916–7. 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1916-1917.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miriagou V, Filip R, Coman G, Tzouvelekis LS. Expanded-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella strains in Romania. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4334–6. 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4334-4336.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Sanz R, Herrera-León S, de la Fuente M, Arroyo M, Echeita MA. Emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and AmpC-type β-lactamases in human Salmonella isolated in Spain from 2001 to 2005. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:1181–6. 10.1093/jac/dkp361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batchelor M, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ, Clifton-Hadley FA, Stallwood AD, Davies RH, et al. Characterization of AmpC-mediated resistance in clinical Salmonella isolates recovered from humans during the period 1992 to 2003 in England and Wales. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2261–5. 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2261-2265.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke L, Hopkins KL, Meunier D, de Pinna E, Fitzgerald-Hughes D, Humphreys H, et al. Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins in human non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica isolates from England and Wales, 2010–12. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:977–81. 10.1093/jac/dkt469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piddock LJ. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella serovars isolated from humans and food animals. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26:3–16. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00596.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrysiak AK, Olson AB, Tracz DM, Dore K, Irwin R, Ng LK, et al. ; Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Collaborative. Genetic characterization of clinical and agri-food isolates of multi drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg from Canada. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:89. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigation update: multistate outbreak of human Salmonella Heidelberg infections linked to “kosher broiled chicken livers” from Schreiber Processing Corporation. 2012. Jan 11 [cited 2015 Jul 23]. http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/2011/chicken-liver-1-11-2012.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed methods and materials used in study of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg strains, the Netherlands.