Abstract

Metabolic sugar labeling followed by the use of reagent-free Click chemistry is a demonstrated technique for in vitro cell targeting. However, selective metabolic labeling of the target tissues in vivo remains a challenge to overcome, which has prohibited the use of this technique for targeted in vivo applications. Here we report the use of targeted ultrasound pulses to induce the release of tetraacetyl N-azidoacetylmannosamine (Ac4ManAz) from microbubbles (MBs) and its metabolic expression in the cancer area. Ac4ManAz-loaded MBs showed great stability under physiological conditions but rapidly collapsed in the presence of tumor-localized ultrasound pulses. The released Ac4ManAz from MBs was able to label 4T1 tumor cells with azido group and significantly improved the tumor accumulation of dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-Cy5 via subsequent Click chemistry. We demonstrated for the first time that Ac4ManAz loaded MBs coupled with the use of targeted ultrasound could be a simple but powerful tool for in vivo cancer-selective labeling and targeted cancer therapies.

Keywords: cancer targeting, cell labeling, click chemistry, drug design, sugar, ultrasound

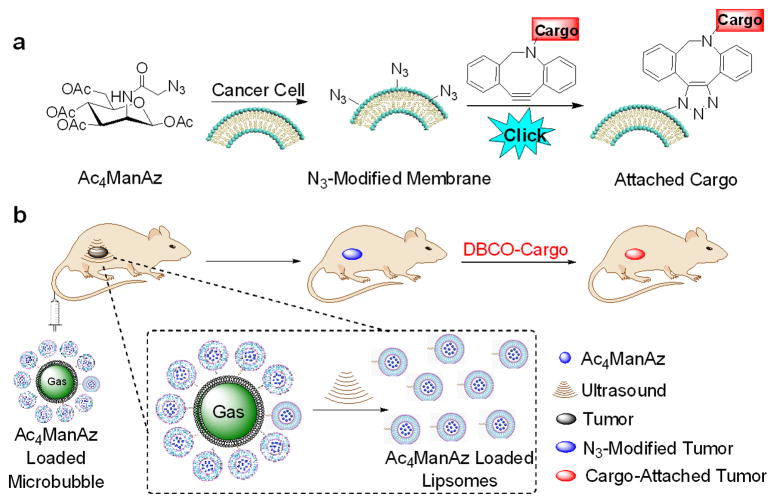

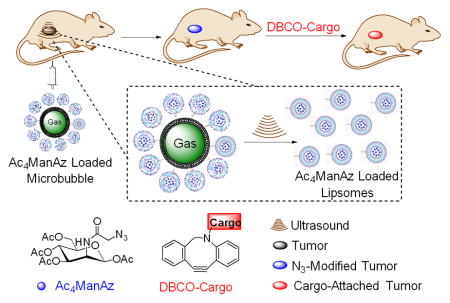

Graphical Abstract

Ac4ManAz loaded microbubble enables cancer targeted labeling and imaging with the assistance of targeted ultrasound.

As an efficient method of incorporating chemical groups into cell surface glycoproteins, metabolic labeling of unnatural sugars has been widely used for glycan visualization, glycoproteomics, and cell labeling.[1–3] Recently, researchers have shown increasing interest in applying it to cancer targeting by coupling with bioorthogonal chemistries.[4–6] In the first step, unnatural sugars with reactive chemical groups (e.g., azides) are delivered and metabolized in the cancerous tissues, followed by the targeted delivery of dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-bearing therapeutics via the Click chemistry in the second step. Despite being a two-step process, this combinational strategy has several advantages in cancer targeting: 1) excellent targeting can be achieved by taking advantage of the rapid, highly efficient Click chemistry; 2) receptor saturation and immunogenicity problems in conventional protein-based targeting strategies can be avoided by using manually installed chemical receptors;[7–9] and 3) small-molecule DBCO as targeting ligands can be easily incorporated into therapeutic agents or nanomedicines with tunable density. One key challenge in using this two-step strategy for in vivo cancer targeting is to specifically deliver the azido-sugars to the cancerous tissues. Kim et al.[6] used chitosan nanoparticles to deliver azido-sugars to cancers by taking advantage of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect of nanoparticles, but the targeting efficiency was very low with limited selectivity.

Ultrasound (US) imaging is widely used and recognized as a safe medical tool for disease diagnosis and treatment.[10–13] Microbubbles (MBs) that entrap gas in a biocompatible material to form micron-sized particles have achieved great success as US contrast agents (UCAs) due to their high US reflectivity and great stability.[14] It is well established that high-amplitude US pressures cause expansion and contraction of MBs, resulting in their disruption.[15–17] A secondary effect of MB destruction is the temporary increase of capillary permeability and production of transient poration in cell membranes.[18–21] Researchers have reported the use of US pulses to burst MB-liposome conjugates and release the encapsulated drugs or genes specifically in the target tissues.[22–25] We envision that cancer-localized US pulses with accurate tissue targeting capability can potentially be used to induce the release of azido-sugars from MBs specifically in the cancerous tissues.[26–28] Here we report the design of tetraacetyl N-azidoacetylmannosamine (Ac4ManAz)-loaded MBs (Ac4-MBs) for effective in vivo cancer-selective labeling (Scheme 1). In the presence of high-amplitude US pressures localized in the cancerous tissues, the MBs collapsed and released azido-sugar loaded liposomes, and meanwhile the temporarily increased capillary and cellular permeability facilitated the tumor penetration and cellular uptake of the released liposomes.[29–31] The released Ac4ManAz then metabolically labeled the tumor cells with azido groups which mediated targeted retention of DBCO-cargo for cancer imaging and potential cancer treatment.

Scheme 1.

(a) Metabolic labeling of Ac4ManAz and subsequent targeting of DBCO-cargo via copper-free Click chemistry. (b) Ultrasound-assisted accumulation and metabolic expression of Ac4ManAz in the tumor area and subsequent tumor targeted delivery of DBCO-cargo via Click chemistry.

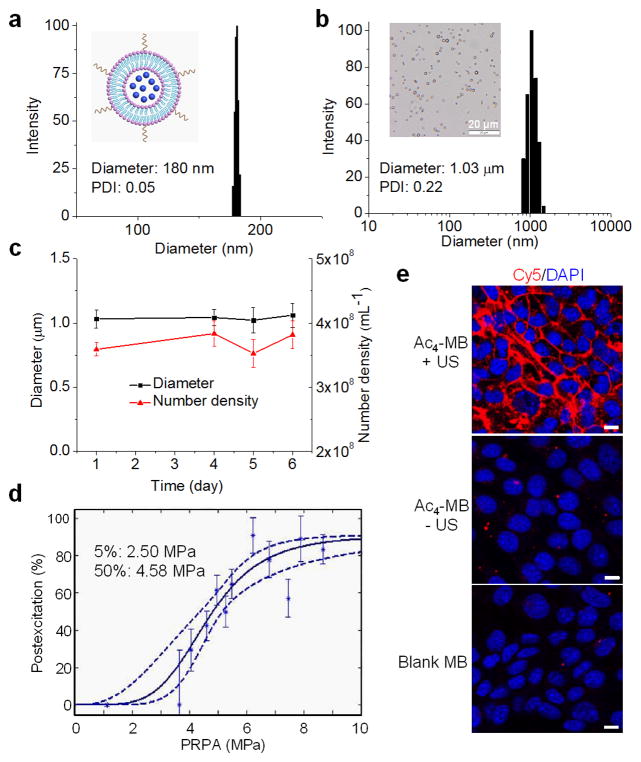

Ac4ManAz-loaded liposomes (Ac4-lipo) functionalized with activated carboxylates were prepared via extrusion of the lipid mixture of hydrogenated L-α-phosphatidylcholine (HSPC), cholesterol and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[succinimidyl (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2k-NHS). The prepared Ac4-lipo had a mean diameter of 180 nm and a sugar loading of 5.3% (w/w) (Fig. 1a, S1). Ac4-lipo showed excellent stability and minimal premature sugar release under physiological conditions (Fig. S2). Amine-functionalized, perfluorobutane gas filled MBs with a mean diameter of 870 nm were prepared using the one-step sonication method (Fig. S2). Ac4ManAz-loaded liposomes were then conjugated to MBs via the coupling reaction between activated carboxylates and amine groups. The resulting Ac4-MB had a mean diameter of 1.03 μm and a narrow polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.22 (Fig. 1b). Blank MB without Ac4ManAz was prepared similarly (Fig. S2). Ac4-MB showed excellent stability under physiological conditions, as evidenced by the negligible change in diameter and number density over 6 days (Fig. 1c). However, in the presence of high-amplitude US pressures, the MBs collapsed. The US pressures applied to collapse 5% and 50% of the Ac4-MB population were 2.50 and 4.58 MPa, respectively (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

(a) Diameter and diameter distribution of Ac4ManAz loaded liposome. (b) Diameter and diameter distribution of Ac4-MB. Inset: microscopic image of Ac4-MB. (c) Change of diameter and number density of Ac4-MB over time in 10% fetal bovine serum. (d) Percentage postexcitation (collapse) curve for Ac4-MB, plotted against peak rarefactional pressure amplitude (PRPA). (e) CLSM images of 4T1 cells after treated with Ac4-MB with or without one-minute US treatment for three days, followed by labeling with DBCO-Cy5 for 1 h. Cells treated with blank MB and labeled with DBCO-Cy5 were used as control. The cell nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 10 μm.

We next studied whether Ac4-MB was able to metabolically label 4T1 breast cancer cells with azido groups when exposed to an US pressure field. 4T1 cells in Ac4-MB containing medium were treated with US for 1 min, further incubated for 3 days, and then treated with DBCO-Cy5 for 1 h to detect the expression of azido groups. The group without US treatment was used as control. As shown in Fig. 1e, minimal Cy5 fluorescence intensity (FI) was observed on the surface of 4T1 cells in the absence of US treatment, indicating the great stability and minimal premature sugar release of MBs during incubation. Because of its relatively large size, Ac4-MB was unable to enter the 4T1 cells and thus failed to release Ac4ManAz in cells for metabolic labeling. In comparison, 4T1 cells exposed to high-amplitude US pressures showed strong Cy5 FI on the cell surface, suggesting that Ac4-lipo were successfully released from the MBs, entered 4T1 cells via endocytosis, and released Ac4ManAz for subsequent metabolic labeling of cells. Presumably, liposomes released the encapsulated azido-sugars via fusion with cellular or intracellular membranes or via lytic degradation in the lysosomes.[32–35] We also tested the in vitro labeling kinetics of Ac4-lipo by incubating it with 4T1 cells for different time and subsequently detecting the cell-surface azido groups using DBCO-Cy5. As a result, Ac4-lipo mediated labeling of 4T1 cells was time-dependent, with the cell-surface azido density approaching to a plataeu value during 72–96 h (Fig. S5).

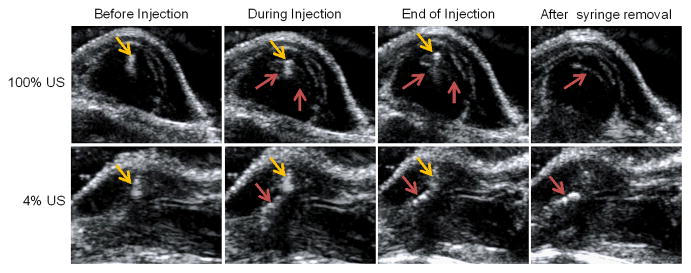

After demonstrating in vitro that Ac4-MB was able to metabolically label 4T1 breast cancer cells with azido groups only in the presence of US, we then went on to study whether targeted US pulses in the tumor area could be used to induce selective sugar labeling of tumor cells. As a proof-of-concept study, we first investigated whether targeted US in the tumor area could break intratumorally injected Ac4-MB and induce metabolic labeling of tumor cells. Ac4-MB was injected directly into the subcutaneous 4T1 tumors on the flanks of BALB/c mice with simultaneous treatment of targeted US. The right tumors were treated with high-amplitude US pressure pulses (the US system’s output was set to the maximum, i.e., 100%, to collapse MBs), while the left tumors were treated with low-amplitude US pressure pulses (the US system’s output was set to a very low amplitude, i.e., 4%, so that the MBs would not collapse and yet still provide US imaging capability) (Fig. S7a, S7b). Ac4-MB injected into the right tumors collapsed and rapidly diffused away during injection in the presence of 100% US (upper panel, Fig. 2). In comparison, most of Ac4-MB injected into the left tumors with 4% US treatment remained intact and deposited near the injection site (lower panel, Fig. 2). Western blot analyses of tumor tissues at 72 h post injection (p.i.) of Ac4-MB showed the existence of more azido-modified protein bands in the right tumors treated with 100% US than in the left tumors treated with 4% US (Fig. S7c), suggesting the enhanced metabolic labeling of tumor cells in the presence of high-amplitude US pressure.

Fig. 2.

US imaging of the tumor area of BALB/c mice during the intratumoral injection of Ac4-MB. 100% and 4% US was applied to the right and left tumors, respectively, upon MB injection (1 min), and continuously applied for another 1 min after MB injection. The yellow arrow indicates the syringe, and the red arrow indicates the MBs.

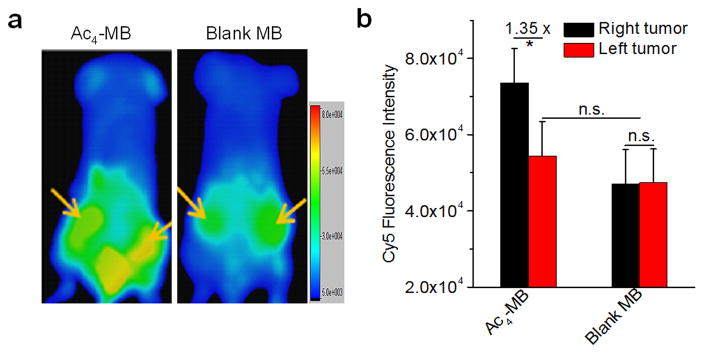

To understand how the enhanced azido expression in the right tumors would improve the tumor accumulation of DBCO-cargo via the Click reaction, in a separate study, DBCO-Cy5 was intravenously (i.v.) injected via the tail vein and its biodistribution was monitored via in vivo fluorescence imaging. At 24 h or 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5, a distinct difference in Cy5 FI between the right tumors treated with 100% US and left tumors treated with 4% US was observed (Fig. 3a, S7d), while mice injected with blank MB showed negligible difference in Cy5 FI between the right and left tumors (Fig. 3a, S7d). Ex vivo fluorescence imaging showed a 1.35-fold Cy5 FI in the right tumor compared to the left tumor in Ac4-MB group (Fig. 3b). In comparison, negligible difference in Cy5 FI between the right and left tumors was observed in the blank MB group (Fig. 3b). It is noteworthy that the left tumors of Ac4-MB group with 4% US treatment showed a statistically non-significant change of Cy5 FI compared to the tumors of the blank MB group (Fig. 3b), suggesting the good stability of Ac4-MB in the tumor environment. Confocal images of the right tumor sections also showed much stronger Cy5 FI than the left tumor sections in Ac4-MB group (Fig. S7h). These findings are significant wherein they demonstrate that targeted US pressure in the tumor area collapsed the intratumorally injected Ac4-MB and facilitated the release and metabolic expression of Ac4ManAz. The expressed azido groups were able to significantly enhance the tumor accumulation of DBCO-Cy5 via the efficient Click reaction.

Fig.3.

(a) In vivo whole body fluorescence imaging of BALB/c mice pretreated with Ac4-MB and blank MB, respectively, at 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5. (b) Ex vivo FI of tumors from BALB/c mice pretreated with Ac4-MB and blank MB, respectively, at 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n=3) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA (Fisher; 0.01 < *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001).

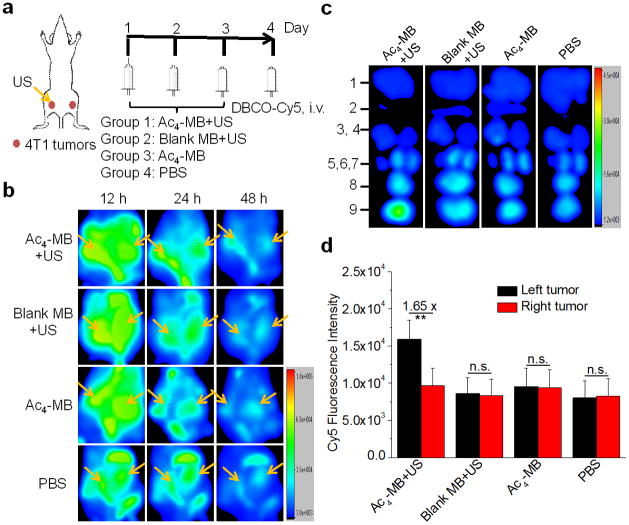

After demonstrating that targeted US was able to collapse intratumorally injected Ac4-MB, we next investigated whether targeted US in the tumor area could collapse Ac4-MB that was injected systemically and subsequently induce the tumor accumulation and metabolic expression of Ac4ManAz. BALB/c mice bearing subcutaneous 4T1 tumors were divided into four groups: Ac4-MB with US treatment on the left tumors (Group 1); blank MB with US treatment on the left tumors (Group 2); Ac4-MB without US treatment (Group 3); and PBS without US treatment (Group 4). MB injections and targeted US exposures were given once daily for three days (Day 1, 2, and 3). DBCO-Cy5 was i.v. injected on Day 4 and its biodistribution was monitored via in vivo fluorescence imaging (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4b, a clear Cy5 fluorescence contrast between the left tumors with US treatment and the right tumors without US treatment was observed in Group 1 mice at 24 h and 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5. In comparison, negligible difference in DBCO-Cy5 signal between the left and right tumors was observed in Group 2 mice without the sugar treatment and in Group 3 mice without the US treatment. Ex vivo imaging showed a 1.65-fold Cy5 FI in the left tumors compared to the right tumors in Group 1 mice, with no significant difference in Cy5 FI between the left and right tumors observed in all other groups (Fig. 4c, 4d). In comparison, healthy organs including liver, spleen, lung, brain, heart, and kidney showed negligible difference for the amount of retained Cy5 among all groups (Fig. S8b, S8c). These findings demonstrated that targeted US could improve the accumulation and expression of Ac4ManAz specifically in the tumor area, presumably as a result of the easier tumor penetration of released Ac4-lipo in the presence of the US exposure. In comparison with the three-injection regimen, mice administered with one i.v. injection of Ac4-MB showed a 1.16-fold accumulation of DBCO-Cy5 in the left tumors with US treatment compared to the right tumors without US treatment (Fig. S9), which suggested that azido labeling of tumors and subsequent tumor targeting of DBCO-cargo could be further improved by increasing the dose of Ac4-MB.

Fig.4.

(a) Time frame of in vivo imaging study. When 4T1 tumors in both flanks of BALB/c mice reached a diameter of approximately 5 mm, the hair over the tumor area was shaved and depilated, and Ac4-MB (50 mg/kg in sugar equivalent) or blank MB (same amount of MB) was i.v. injected with simultaneous US exposures on the left tumors once daily for three days. On Day 4, DBCO-Cy5 (5 mg/kg) was i.v. injected. (b) In vivo whole body fluorescence imaging of BALB/c mice at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5, respectively. (c) Ex vivo imaging of tumors and major organs at 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5. 1-liver, 2-spleen, 3-lung, 4-brain, 5-heart, 6,7-kidneys, 8-right tumor, 9-left tumor. (d) Quantification of Cy5 FI in tumors from (c). Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n=3) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA (Fisher; 0.01 < *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001).

To further understand the benefits of the two-step targeting strategy of Ac4-MB and Click chemistry, we evaluated the tumor targeting efficiency of Cy5-labeled MB (Cy5-MB) in the presence of tumor-targeted US. BALB/c mice bearing subcutaneous 4T1 tumors were i.v. injected with Cy5-MB, with simultaneous US treatment on the left tumors. The right tumors without US treatment were used as controls. At 48 h p.i. of Cy5-MB, ex vivo imaging of harvested tissues showed a statistically non-significant change of Cy5-MB accumulation between the left and right tumors (Fig. S10), in sharp contrast to the 1.65-fold tumor targeting efficiency achieved by the combinational strategy of Ac4-MB and DBCO-Cy5 (Fig. 4d). In addition, the vast majority of Cy5-MB accumulated in liver and lung, showing an extremely low tumor-to-organ accumulation ratio (Fig. S10). These experiments validated that Ac4-MB coupled with DBCO-cargo can not only mediate a much higher cancer-targeting efficiency than cargo-loaded MB, but also enables the choice of cargo-delivery systems with more favorable pharmacokinetics than MB. In another set of experiments, we i.v. injected Ac4-MB into BALB/c mice once daily for three days with simultaneous US treatment on the right thigh muscles, and then i.v. injected DBCO-Cy5. At 48 h p.i. of DBCO-Cy5, the right thigh muscles with US treatment failed to show an increase of DBCO-Cy5 accumulation compared to the left thigh muscles without US treatment (Fig. S11), which together with the achieved 1.65-fold tumor-targeting effect (Fig. 4d) suggested that sugar expression in cancerous tissues was more favored than in normal tissues.

In summary, we developed Ac4-MB for cancer targeted labeling and imaging with the assistance of targeted US. Targeted US pulses could induce the collapse of Ac4-MB (while being visualized under US imaging) and the release and metabolic expression of azido-sugars within the tumor, which significantly increased the tumor accumulation of DBCO-Cy5 by 65% via the Click reaction compared to the group without US treatment. More importantly, the accumulation of DBCO-Cy5 in healthy tissues showed negligible change. Different from antibody-drug conjugate[36] and nanoparticle-targeting ligand conjugate[37–40] based targeting strategies which improved the cellular uptake instead of the overall tumor-organ accumulation ratio of drugs or drug delivery systems, our strategy can intrinsically enhance the tumor-organ accumulation ratio of therapeutic agents. Ac4-MB coupled with the use of targeted US could be a simple but powerful tool for in vivo cancer targeting and targeted cancer therapies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH (Director’s New Innovator Award 1DP2OD007246), NSF (DMR 1309525) and NIH (R37EB002641). H. Wang is funded by Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research Fellowship.

Contributor Information

Hua Wang, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States.

Marianne Gauthier, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States.

Jamie R. Kelly, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States

Rita J. Miller, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States

Ming Xu, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States.

Prof. Dr. William D. O’Brien, Jr., Email: wdo@uiuc.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States

Prof. Dr. Jianjun Cheng, Email: jianjunc@illinois.edu, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States

References

- 1.Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Baskin JM, Carrico IS, Chang PV, Ganguli AS, Hangauer MJ, Lo A, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 415. Academic Press; 2006. p. 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prescher JA, Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Nature. 2004;430:873. doi: 10.1038/nature02791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laughlin ST, Baskin JM, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR. Science. 2008;320:664. doi: 10.1126/science.1155106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koo H, Lee S, Na JH, Kim SH, Hahn SK, Choi K, Kwon IC, Jeong SY, Kim K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:11836. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukase K, Tanaka K. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:614. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Koo H, Na JH, Han SJ, Min HS, Lee SJ, Kim SH, Yun SH, Jeong SY, Kwon IC, Choi K, Kim K. ACS Nano. 2014;8:2048. doi: 10.1021/nn406584y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khazaeli M, Conry RM, LoBuglio AF. J Immunol. 1994;15:42. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:220. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteva FJ. J Oncologist. 2004;9:4. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-suppl_3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose FH, McGregor CD, Mathur P. 4, 896, 673. US Patent. 1990

- 11.Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW. Diagnostic ultrasound. Vol. 2. Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heimdal A, Støylen A, Torp H, Skjærpe T. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1998;11:1013. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(98)70151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien WD., Jr Prog Biophys Mol Bio. 2007;93:212. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindner JR. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:527. doi: 10.1038/nrd1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christiansen JP, French BA, Klibanov AL, Kaul S, Lindner JR. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1759. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bekeredjian R, Chen S, Frenkel PA, Grayburn PA, Shohet RV. Circulation. 2003;108:1022. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084535.35435.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu Q, Liang H, Partridge T, Blomley M. Gene Ther. 2003;10:396. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentice P, Cuschieri A, Dholakia K, Prausnitz M, Campbell P. Nat Phys. 2005;1:107. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita M, McDannold N, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:11719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604318103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treat LH, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Zhang Y, Tam K, Hynynen K. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:901. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbes MM, O’Brien WD. J Acoust Soc Am. 2012;131:2723. doi: 10.1121/1.3687535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang SL. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1167. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki R, Takizawa T, Negishi Y, Hagisawa K, Tanaka K, Sawamura K, Utoguchi N, Nishioka T, Maruyama K. J Control Release. 2007;117:130. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrara K, Pollard R, Borden M. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki R, Namai E, Oda Y, Nishiie N, Otake S, Koshima R, Hirata K, Taira Y, Utoguchi N, Negishi Y. J Control Release. 2010;142:245. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlin CJ, Harasiewicz K, Sherar MD, Foster FS. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:287. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Jaffin JH, Champion HR. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1993;34:516. [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Wolfson S, Bond MG, Bommer W, Sheth S, Psaty BM, Sharrett AR, Manolio TA. Stroke. 1991;22:1155. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.9.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hitchcock KE, Caudell DN, Sutton JT, Klegerman ME, Vela D, Pyne-Geithman GJ, Abruzzo T, Cyr PE, Geng YJ, McPherson DD. J Control Release. 2010;144:288. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeder A, Kost J, Barenholz Y. Chem Phys Lipids. 2009;162:1. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder A, Honen R, Turjeman K, Gabizon A, Kost J, Barenholz Y. J Control Release. 2009;137:63. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal R, Iezhitsa I, Agarwal P, Abdul Nasir NA, Razali N, Alyautdin R, Ismail NM. Drug Deliv. 2014;1 doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.943336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mo R, Jiang T, Gu Z. Angew Chem. 2014;126:5925. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paliwal SR, Paliwal R, Agrawal GP, Vyas SP. Nanomedicine. 2011;6:1085. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Peters T, Sindrilaru A, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1100. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirpotin DB, Drummond DC, Shao Y, Shalaby MR, Hong K, Nielsen UB, Marks JD, Benz CC, Park JW. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farokhzad OC, Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Jon S, Kantoff PW, Richie JP, Langer R. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:6315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601755103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Sung J, Luther G, Gu FX, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Radovic-Moreno AF, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Biomaterials. 2007;28:869. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang L, Yang X, Dobrucki LW, Chaudhury I, Yin Q, Yao C, Lezmi S, Helferich WG, Fan TM, Cheng J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:12721. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Z, Tong R, Mishra A, Xu W, Wong GCL, Cheng J, Lu Y. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2009;48:6494. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.